Abstract

Background

The healthcare burden posed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic in the New York Metropolitan area has necessitated the postponement of elective procedures resulting in a marked reduction in cardiac catheterization laboratory (CCL) volumes with a potential to impact interventional cardiology (IC) fellowship training.

Methods

We conducted a web‐based survey sent electronically to 21 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited IC fellowship program directors (PDs) and their respective fellows.

Results

Fourteen programs (67%) responded to the survey and all acknowledged a significant decrease in CCL procedural volumes. More than half of the PDs reported part of their CCL being converted to inpatient units and IC fellows being redeployed to COVID‐19 related duties. More than two‐thirds of PDs believed that the COVID‐19 pandemic would have a moderate (57%) or severe (14%) adverse impact on IC fellowship training, and 21% of the PDs expected their current fellows' average percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) volume to be below 250. Of 25 IC fellow respondents, 95% expressed concern that the pandemic would have a moderate (72%) or severe (24%) adverse impact on their fellowship training, and nearly one‐fourth of fellows reported performing fewer than 250 PCIs as of March 1st. Finally, roughly one‐third of PDs and IC fellows felt that there should be consideration of an extension of fellowship training or a period of early career mentorship after fellowship.

Conclusions

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused a significant reduction in CCL procedural volumes that is impacting IC fellowship training in the NY metropolitan area. These results should inform professional societies and accreditation bodies to offer tailored opportunities for remediation of affected trainees.

Keywords: coronavirus disease, fellowship training, interventional cardiology, procedural volume

1. INTRODUCTION

The New York (NY) metropolitan area has emerged as an epicenter of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) global pandemic with over 100,000 cases and 5,000 deaths by the beginning of April 2020. 1 , 2 , 3 In line with governmental recommendations, 4 , 5 professional societies, including the American College of Cardiology and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, have recommended deferral of elective cardiac, endovascular, or structural catheterization procedures during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 6 , 7 Beginning even before these directives, NY regional institutions severely restricted elective invasive procedures, including cardiac catheterization. A simultaneous decline in the number of patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes in regions severely affected by the pandemic has also been observed. 8 , 9 , 10 Together, these factors have resulted in a dramatic decline in cardiac catheterization laboratory (CCL) procedural volumes in the NY area that is expected to continue for several months based on regional pandemic projections. 11 This and related changes in clinical practice have the potential to impact IC fellowship training in a major fashion.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recognizes interventional cardiology (IC) as a specialty with a required 12‐month training period, during which IC fellows are expected to achieve the necessary cognitive and technical skills for independent practice. 12 As a procedural specialty, minimal procedural volumes are required of IC fellows to ensure the development of appropriate technical skills. The purpose of this study was to explore the perceived and actual impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on IC fellowship training in the NYC metropolitan area through a survey of IC fellowship program directors (PDs) and current fellows.

2. METHODS

We conducted a voluntary, web‐based survey of PDs and current fellows of IC fellowships in NYC and northern New Jersey (NJ). The surveys were disseminated utilizing SurveyMonkey to both the PDs (email message with a web link) and IC fellows (individual PDs forwarded web link to fellows) (both surveys included in Supplement). Fellows enrolled in either 1‐year ACGME accredited or advanced the second year coronary (CHIP/CTO), endovascular, or structural heart IC programs were included. The PD survey included 12 multiple‐choice questions (with an additional four questions for programs with advanced second year programs) and the fellow survey included 11 multiple‐choice questions (six for advanced fellows). Individual responses were downloaded from the survey and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Descriptive analyses are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for continuous variables. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

3. RESULTS

Of 21 IC fellowship PD's who were invited to participate, 14 (response rate, 67%) responded to the survey. The PDs estimated the average monthly percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) volume of their respective institutions prior to March to be <50 (7%), 51–100 (21%), 101–150 (14%), and >150 (57%) cases. More than 70% of the programs expected their institutional PCI volume to be less than 25 cases in April 2020. At least half of the PD's reported part of their CCL area being converted to an inpatient COVID‐19 unit (57%) and their fellows being redeployed to other clinical areas (50%).

All of the PDs reported that the average number of PCIs performed by IC fellows in prior years was more than 300 with 57% of PD's reporting average fellow PCI volumes of more than 400 cases. However, for the current fellowship class, 21% of the PDs expected their fellows' average PCI volume to be below the ACGME requirement of 250 PCIs, and an additional 14% expected the average PCI volume to be less than 300 PCIs. To supplement the decline in PCI volume, a majority (57%) of the PDs felt that the number of coronary physiology or intravascular imaging procedures should be included in the PCI procedure log for this year's class.

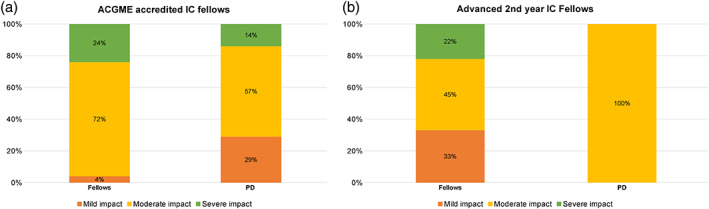

More than half of the PDs (57%) felt that the COVID‐19 pandemic would have a moderate adverse impact on training, while 14% felt it would be severe (Figure 1(a)). Of the PDs surveyed, 14% felt that at least one of their trainees would not achieve the required technical competence by the end of training and 29% believed there should either be an extension of training or a period of on‐the‐job mentorship for the current class (Table S1). PDs subjectively expressed concern that the loss of the last 3–4 months of fellowship when IC fellows gain autonomy and develop critical‐thinking/decision‐making ability could have a significant adverse impact on training (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic on IC fellowship training. Panel A: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accredited IC fellows; Panel B: Advanced second year IC fellows. Abbreviation: IC, interventional cardiology [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

Narrative impressions of impact of COVID‐19 on training

| Comments | |

|---|---|

| Program Directors | |

| Negative sentiment |

|

|

|

|

|

| Neutral sentiment |

|

|

|

| Positive sentiment |

|

|

|

|

Interventional Cardiology Fellows Negative sentiment |

|

|

|

|

|

| Neutral sentiment |

|

Of the 41ACGME accredited IC fellows who were sent the survey, 25 (61%) responded. Twenty‐four percent reported performing fewer than 250 PCIs (12% 150–200 PCIs and 12% 201–250 PCIs) as of March 1, 2020. With respect to the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on their training, 72% of fellows responded that it had a moderate adverse impact, while 24% felt it was severe (Figure 1a). Only half of the respondents felt very confident they would achieve technical competence by the end of the fellowship (Figure 2). Twenty eight percent of the IC fellows planned to pursue an advanced second year IC fellowship in July 2020. Of the remaining fellows seeking a job, one reported that a prospective employer had withdrawn an existing job offer. One‐third of the fellows felt that there should be either an extension of training or a dedicated period of mentorship after fellowship (Table S2). Subjectively, fellows expressed disappointment about the interruption in fellowship training and concerns about procedural competence, gaining autonomy, and future job prospects (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Level of confidence of fellows to achieve adequate technical competence by end of training. Abbreviation: IC, interventional cardiology [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Of 14 programs that participated in the survey, four had an advanced second year fellowship in complex coronary, endovascular, or structural heart intervention. All PDs felt that the COVID‐19 pandemic would cause only a moderate impact on advanced fellows' training and none was concerned about the trainees being able to achieve adequate technical competence. Among the advanced IC fellow respondents (N = 13, of which 9 [69%] responded), 78% already had already secured a job after fellowship. Most fellows felt that the pandemic would cause a mild (33%) or moderate impact (45%) on their training and 67% were very confident about being able to achieve technical competence (Figures 1b and 2). All PD's and 89% of the advanced fellow respondents felt that there was no need for training extension or extra mentorship for advanced IC fellowship trainees.

4. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is resulting in reduced training time and procedural volume for current IC fellows due to a severe drop in CCL case volume as well as clinician redeployment across the health care system during the final quarter of the 2019–2020 academic year. To capture the impact on fellow training in the NY metropolitan area, we conducted a survey of the IC fellowship programs in this region. The principal findings of our study are that (a) CCL procedural volumes have dramatically decreased in all programs, (b) the majority of PDs and especially fellows perceive that IC fellowship training has been significantly impacted by the pandemic, and (c) mitigation plans will be needed to help current IC fellows transition into independent practice.

The results from the survey raise important questions regarding IC fellowship training: (a) Is the requirement for a 12‐month clinical training program truly met? (b) Will the requirement for the minimum procedural numbers be satisfied? (c) Will the majority of fellows be comfortable practicing as independent providers given the effective loss of the critical third of their training during which they gain independence and autonomy? (d) Will job opportunity and security be affected by the pandemic? Our survey results shed some important insights on these potential impacts as perceived by both the IC fellowship PDs and trainees.

Procedural competence in IC includes a cognitive skillset focused on advanced procedural decision making and autonomy. These cognitive skills are typically consolidated toward the latter end of the training period, after fellows have achieved technical competence. Unfortunately, it is the critical final quarter of the academic year that is being affected for the current class of fellows. The ACGME has already recognized that procedural trainees might not be able to achieve the minimal specialty‐specific case requirement in the current year, but has emphasized that PDs and clinical competency committees must nevertheless continue to assess the competence of individual trainees to enter unsupervised practice. 13 It is our belief that programs should continue to strive to teach these critical components of procedural competence through the use of adaptive learning methods such as teleconferenced didactics, “taped cases,” cineangiogram review sessions, and simulation training.

The ACGME training pathway in IC currently requires 12 months of satisfactorily completed clinical fellowship training during which IC fellows must perform at least 250 therapeutic interventional cardiac procedures. In addition, to be board eligible, the PDs must determine that the fellows have accomplished satisfactory ratings in the six ACGME core competencies and in overall clinical comptence. 12 , 14 The effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on IC procedural volumes may lead to challenges in meeting these fellowship requirements. While our survey indicates that most PD's expect their fellows to achieve the minimum benchmark of 250 PCIs, this represents a significant decline in the average PCI volume for their current fellows compared with prior graduates. As the COVID‐19 pandemic spreads across the country this impact may be further exaggerated in regions where average procedural volumes during IC fellowship are not as high at baseline. Although not a perfect surrogate for competence, the procedural volume is a measurable metric and it is intuitive that blocked repetition of technical manipulations involved in PCI would correlate with the development of necessary manual skills. Therefore, there is likely to be at least a modest adverse impact on the technical skills of this years' graduating IC fellows. It is interesting to note that in this respect, fellows perceived a greater impact on their training than did the PDs.

Our survey data suggest that the current crisis likely had a relatively lesser effect on the training of advanced second year fellows in interventional subspecialties. Both PDs and fellows reported only a moderate impact on training and most fellows felt very confident of their technical skills. This is anticipated as second year IC fellows have already successfully completed 12 months of accredited interventional training and probably acquired the critical skillsets expected of their procedural subspecialty before the last few months of training.

In addition to the training concerns, the stability of the job market is a concern for many trainees. We are early in the pandemic, and as the financial impact of this crisis on the healthcare industry begins to be felt, it is possible that more offers will be withdrawn or salaries will be reduced. New fellowship graduates may be further impacted by this since they may endure another period of minimal procedural volume. Notably, almost a third of PD's and IC fellows respondents felt that there was a potential need for extension of fellowship training or a dedicated period of mentorship after fellowship. We do acknowledge that either approach has its own challenges. Extension of fellowship training could lead to additional stress on an already stretched healthcare system and potentially also lead to a competition for procedural experience with incoming fellows in July. Opportunities for mentorship post‐fellowship would vary widely with the practice setting and also give rise to concerns about compensation models. Therefore, a tailored approach for individual trainees based on their experience, skillset, and competence would likely be the most suitable. Although the negative impact of the pandemic on training is likely real in NY metropolitan area, the crisis has also provided a special time of cooperation, adaptation, dedication, and learning among interventional cardiologists which in the long run may prove more valuable than procedural volume lost.

5. LIMITATIONS

Our study was subject to leading question and voluntary response bias that are inherent to questionnaire surveys. Our response rates were modest and it is possible that higher response rates would have increased generalizability of our results. We sent two additional email reminders to the invited fellowship programs, but this may reflect the fact that many PDs and IC fellows are currently supporting the numerous patient‐facing roles in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Although our survey sample was limited to NY metropolitan area programs, this region is the worst affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States and our findings will likely be relevant to other geographic regions as the pandemic curves evolve in the remainder of the country.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This survey highlights the adverse impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on IC fellowship training from the perspective of both fellows and training directors. Our data should inform training programs, accreditation bodies, and professional societies to offer tailored opportunities for remediation of affected trainees after fellowship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Bortnick has served as site PI for multicenter trials funded by Abbott and CSL‐Behring, for which her institution received compensation; honorarium from ClearView Healthcare, LLC; support from an AHA Mentored and Clinical Population Award 17MCPRP33630098 and a K23 HL146982 from the NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Dr. Feit reports stock holdings in Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Leon reports clinical research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards, and Medtronic. Dr Parikh reports institutional grants/research support from Abbott Vascular, Shockwave Medical, TriReme Medical and Surmodics; consulting fees from Terumo and Abiomed; and Advisory Board participation for Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, CSI, Janssen and Philips. Dr Kirtane reports Institutional funding to Columbia University and/or Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, CathWorks, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical. In addition to research grants, institutional funding includes fees paid to Columbia University and/or Cardiovascular Research Foundation for speaking engagements and/or consulting; no speaking/consulting fees were personally received. Personal: Travel Expenses/Meals from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, CathWorks, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, Chiesi, OpSens, Zoll, and Regeneron. Dr. Kodali reports the following disclosures: Consultant (Honoraria) ‐ Admedus, Meril Lifesciences, JenaValve, Abbott Vascular; SAB (Equity) ‐ Dura Biotech, MicroInterventional Devices, Thubrikar Aortic Valve Inc, Supira, Admedus, and Institutional Funding to Columbia University and/or Cardiovascular Research Foundation from ‐ Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, JenaValve. All other authors have no relevant disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting information

Gupta T, Nazif TM, Vahl TP, et al. Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on interventional cardiology fellowship training in the New York metropolitan area: A perspective from the United States epicenter. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:201–205. 10.1002/ccd.28977

EDITORIAL COMMENT: Expert Article Analysis for: Negative impact of coronavirus on interventional cardiology fellows' training: Let's limit collateral damage of the pandemic

REFERENCES

- 1.Second Case of Coronavirus in N.Y. Sets Off Search for Others Exposed. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/03/nyregion/coronavirus-new-york-state.html. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 2.Coronavirus in New York: Map and Case Count. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/new-york-coronavirus-cases.html. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 3.Coronavirus COVID‐19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 4.COVID‐19: Guidance for ASCs on Necessary Surgeries. https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-state. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 5.Emergency Executive Order No. 100. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/home/downloads/pdf/executive-orders/2020/eeo-100.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 6. Welt FGP, Shah PB, Aronow HD, et al. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic: from ACC's interventional council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372‐2375. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Szerlip M, Anwaruddin S, Aronow HD, et al. Considerations for cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures during the COVID‐19 pandemic perspectives from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Emerging Leader Mentorship (SCAI ELM) members and graduates. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020. 10.1002/ccd.28887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Mystery of the Missing STEMIs During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. https://www.tctmd.com/news/mystery-missing-stemis-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 9.Where Have All the Heart Attacks Gone? https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-hospitals-emergency-care-heart-attack-stroke.html. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 10. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST‐segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;S0735‐1097(20):34913–34915. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. IHME COVID‐19 projections. https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 12. ABIM Interventional Cardiology Policies . https://www.abim.org/certification/policies/internal-medicine-subspecialty-policies/interventional-cardiology.aspx. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 13.ACGME Response to the Coronavirus (COVID‐19). https://acgme.org/Newsroom/Newsroom-Details/ArticleID/10111/ACGME-Response-to-the-Coronavirus-COVID-19. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 14. King SB, Babb JD, Bates ER, et al. COCATS 4 task force 10: training in cardiac catheterization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1844‐1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting information