Abstract

Coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic is the biggest global health threat in the 21st century. We describe a case of a patient with suspected COVID‐19 who needed urgent coronary artery interrogation, in which we utilized robotic assistance to minimize the risk of exposure to COVID‐19 and reduced personal protective equipment needed by the procedural team.

Keywords: coronary intervention, COVID‐19, interventional devices/innovation, robot assisted

Abbreviations

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease‐2019

- iFR

instant wave‐free ratio

- IVUS

intravascular ultrasound

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2

1. INTRODUCTION

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) causing coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) reached pandemic levels in March 2020. 1 The disease wielded great impact on healthcare systems globally straining their resources, exposing large gaps in occupational hazard management and available protective equipment. Thousands of healthcare workers on the frontlines of the COVID‐19 pandemic contracted the disease and hundreds died as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports.

To focus resources on the pandemic at hand, elective cardiac procedures were halted nationwide in the United States. However, patients with life‐threatening cardiac conditions such as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and cardiogenic shock continued to require emergency cardiac catheterization procedures.

Several professional societies and academic bodies issued statements to provide recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an AMI during the COVID‐19 pandemic and maximize the safety of medical personnel by appropriate masking of patients and the use of personal protection equipment (PPE). 2 , 3 Robotic‐assisted percutaneous coronary interventions (R‐PCI) can provide an additional layer of protection to the healthcare personnel involved in the management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 and require urgent or emergent coronary intervention.

2. CASE

2.1. History of presentation

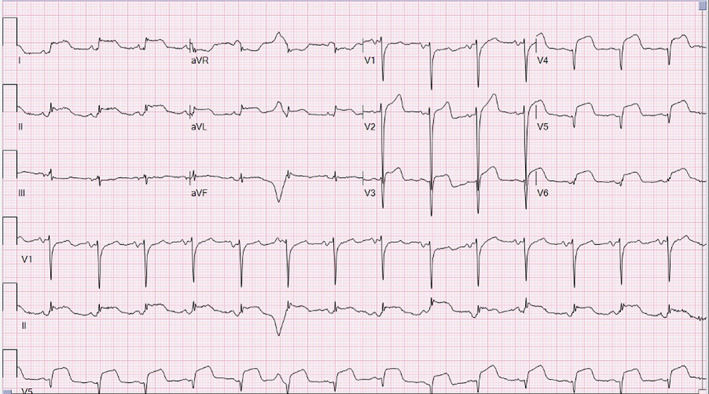

On March 16, a 59‐year‐old female with past medical history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus was brought to the emergency department by emergency medical services after being found unresponsive at her residence. She was resuscitated and intubated. Her electrocardiogram showed ST‐segment elevation in the anterior precordial leads (Figure 1) and the catheterization laboratory was alerted. High oxygen requirements prompted further evaluation with a computed tomography scan, which showed diffuse bilateral infiltrates concerning for an infectious etiology (Figure 2), and thus a polymerase chain reaction test for COVID‐19 was sent.

FIGURE 1.

Electrocardiogram demonstrating ST‐elevations in leads V2–6 and leads I, II, and aVL

FIGURE 2.

Chest computed tomography showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates

2.2. Management

Medical therapy for AMI was initiated using heparin, aspirin, and ticagrelor. Cardiac care teams discussed options regarding her possibly significant coronary artery disease (CAD), while considering multiple factors including patient's unknown COVID status, risk of catheterization laboratory staff exposure, and risk of deferring evaluation of her CAD to a later time. After extensive discussion and concern for clinical deterioration, decision was made to proceed with coronary angiography utilizing full PPE and standard precautions. Arterial access was obtained in the left formal artery, to ensure adequate distance of the access site from the patient's intubated airway, using ultrasound guidance and a micropuncture access kit with placement of a 6‐Fr sheath (Terumo Interventional Systems, Somerset, NJ). After appropriate anticoagulation, selective coronary angiography was performed which showed no evidence of acute plaque rupture but moderate to severe calcified 60% tubular epicardial coronary atherosclerosis involving the proximal portion of the Left Anterior Descending Artery (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Robotic‐assisted percutaneous coronary intervention setup. Note the distance between the robotic arm and the patient while the primary operator is in the cockpit (not shown)

2.3. Robotic‐assisted intervention

At this point, R‐PCI was utilized aiming to further decrease the risk of catheterization laboratory personnel exposure by decreasing the number of personnel at bedside and increasing the distance between the bedside personnel and patient airway.

A CorPath® robotic intervention arm (Corindus Inc., Waltham, MA) was used (Figure 3) to perform further LAD assessment using instant wave‐free ratio (iFR) and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). A Verratta iFR wire (Philips, Andover, MA) was normalized and robotically advanced into the distal LAD. Serial iFR recordings yielded a maximal iFR of 0.92, which was deemed nonsignificant. To further interrogate the diseased segment, an Eagle Eye Platinum digital IVUS catheter (Phillips) was advanced robotically to image the proximal to mid LAD. This revealed an area stenosis of 50% in the proximal LAD with mean luminal area >7.0 mm2, which was deemed nonsignificant. Given the findings mentioned above, the procedure was terminated, and the patient's CAD was determined to be noncontributory to the clinical presentation and treated with conservative medical therapy.

2.4. Follow‐up

The patient's cardiac troponins peaked at 2.4 ng/ml. An echocardiogram showed normal biventricular function with no evidence of pericardial effusion or valvular disease. She was extubated on hospital day 3 and discharged home with instructions for self‐quarantine on hospital day 5 without further episodes of chest pain or breathlessness.

3. DISCUSSION

Occupational health hazards in the catheterization laboratory remains a major challenge for the field of interventional cardiology. The Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention (SCAI) recently issued a multisociety position statement outlining the major risks. 4 The novel challenges specific to the management of patients with COVID‐19 add to the traditional risks. Widespread epidemics like COVID‐19 warrant further improvement in approach to PCI that can mitigate this occupational hazard. R‐PCI holds potential to tackle such issues that involve reduction of contact with the patient during a procedure. R‐PCI has been approved for coronary interventions and has had increasing adoption in elective and complex procedures globally. 5 , 6 After obtaining vascular access and engaging the coronary artery, the operator can stay 6 ft (2 m) away from the patient as recommended by CDC 5 (Figure 3). Furthermore, the scrubbed technician at the table can remain at the end of the table sufficiently distant from the patient. Alternatively, the scrubbed operator, as a single person, can rotate between the tableside and cockpit positions to perform the entire procedure while maintaining distance from patient and minimizing the exposure risk to other personnel. The safety of R‐PCI was evaluated in the PRECISE (Percutaneous Robotically Enhanced Coronary Intervention) trial in which procedural success was seen in 162 out of 164 patients. 6 For complex cases, the CORA‐PCI (Complex Robotically Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) study showed noninferiority when compared with manual PCI. 7 Additional benefits of R‐PCI include reduction in radiation doses, more accurate assessment of lesion length, and precise deployment of coronary balloons and stents. Furthermore, the implementation of remote PCI, which has been successfully demonstrated in nonemergent patient settings with the operator in a geographically distant location outside of the procedural hospital, 8 would allow further reduction of exposure to personnel in these pandemic environments. Finally, by reducing the number of operators needed at bedside, R‐PCI can reduce the amount of PPE that would be utilized for a procedure. This can be of great value especially in times when available resources can be limited.

4. CONCLUSION

R‐PCI can provide an additional layer of protection to the healthcare personnel participating in the management of COVID patients. This may be especially useful in situations where access to PPE is limited, as in the current crisis. Future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of R‐PCI in management of urgent and emergent cardiac catheterization procedures, especially in pandemic environments. Further innovation of this novel technology may result in broader adoption of R‐PCI among the interventional cardiology community.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J. C. G. is a consultant for Cordis, Corindus, and Philips. S. J. is a consultant for Philips. The rest of the authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Tabaza L, Virk HH, Janzer S, George JC. Robotic‐assisted percutaneous coronary intervention in a COVID‐19 patient. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:E343–E345. 10.1002/ccd.28982

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Novel Coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) Situation Report – 51 [Internet]. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 2. Welt FGP, Shah PB, Aronow HD, et al. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic: from ACC's Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2372–2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahmud E, Dauerman HL, Welt FGP, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;S0735109720350269. [Epub ahead of print]. Available online 21 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klein LW, Goldstein JA, Haines D, et al. SCAI multi‐society position statement on occupational health hazards of the catheterization laboratory: shifting the paradigm for healthcare workers' protection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;30:1–7. 10.1002/ccd.28579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) – Prevention [Internet]. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed April 24, 2020.

- 6. Weisz G, Metzger DC, Caputo RP, et al. Safety and feasibility of robotic percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1596‐1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mahmud E, Naghi J, Ang L, et al. Demonstration of the safety and feasibility of robotically assisted percutaneous coronary intervention in complex coronary lesions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1320‐1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel TM, Shah SC, Pancholy SB. Long distance tele‐robotic‐assisted percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of first‐in‐human experience. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;14:53‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]