Abstract

Despite the ferment aroused in the scientific community by the COVID‐19 outbreak and the over 11,000 papers listed in PubMed, published evidence on safe and effective drugs has not progressed yet at the same speed of the pandemic. However, clinical research is rapidly progressing, as shown by the hundreds of registered clinical trials on candidate drugs for COVID‐19. Unfortunately, information on protocols of individual studies differs from registry to registry. Furthermore, study designs, criteria for stratification of patients and choice of outcomes are quite heterogeneous. All this makes data sharing and secondary analysis difficult. At last, small single centre studies and the use of drugs on a compassionate basis should be replaced by highly powered, multi‐centre, multi‐arm clinical trials, in order to provide the required evidence of safety and efficacy of novel or repurposed candidate drugs. Hopefully, the efforts of clinical researchers in the fight against the SARS Cov‐2 will result into the identification of effective treatments. To make this possible, clinical research should be oriented by guidelines for more harmonized high‐quality studies and by a united commitment of the scientific community to share personal knowledge and data. Allergists and clinical immunologists should have a leading role in this unprecedent challenge.

Keywords: biologics, infections, inflammation, lung diseases other than asthma and COPD, pharmacology and pharmacogenomics

1. INTRODUCTION

COVID‐19 has aroused an unprecedented scientific ferment to tackle this deadly pandemic. The most important scientific journals, including Allergy, have created a specific section on COVID‐19. As of May 12, day of submission, a PubMed search for COVID‐19 shows 11 336 papers published in 2020 (almost 10 every working hour). However, this number increases as rapidly as the number of worldwide infected people and deaths reported daily by the WHO and the national authorities. Through this emerging literature, much has been learned on the mechanisms of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, 1 , 2 modes of transmission, incubation period, clinical features, incidence, and lethality of the disease. 3 , 4

Following initial discordant strategies in different countries, 5 there has also been general agreement on the efficacy of the lockdown in China and the strict public health measures firstly implemented in Europe by the Italian government to suppress COVID‐19 diffusion (isolation of areas with a high number of positive cases, closure of nonessential public places, schools and universities, cancelation of congresses, and mass gathering events). Recommendations made by governments for a lockdown—although implemented at different times—appear to be fully justified and supported by accurate modelling on their potential effect on the mitigation or suppression of the infection. 6

On the other hand, the search for an effective therapy of COVID‐19 is still a work in progress, which demands a harmonized approach of the scientific community. This article aims to provide a critical overview of the clinical trials exploring candidate drugs for potential treatment of COVID‐19. The several ongoing clinical trials on SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines do not fall within the scope of this article.

2. THE LEADING ROLE OF ALLERGISTS AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGISTS IN THE FIGHT AGAINST SARS‐COV‐2

There is no doubt that allergists and clinical immunologists should be on the front line in the fight against SARS‐CoV‐2, since their expertise is required for a better understanding of COVID‐19 pathophysiology and its management. First, the host immune response is the main mechanism to block the viral infection and attenuate or prevent symptoms. 7 Second, there is a wide consensus that the progression of the disease to the most severe life‐threatening forms is associated with an intense inflammatory process and a cytokine storm. 7 Third, beyond plasma‐based therapy and vaccines, several candidate drugs against SARS‐CoV‐2 are part of the current therapeutic armamentarium of the clinical immunologist and require the expertise of our specialty. 8

In fact, 39 clinical trials explore the efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti‐IL‐6R (sIL‐6R and mIL‐6R) monoclonal antibody widely used by allergists and clinical immunologists for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, and the CAR‐T‐induced cytokine release syndrome. 9 Some other candidate monoclonal antibodies for COVID‐19 clinical trials—targeting IL‐1, IL‐17A, growth factors, and complement factors—are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Candidate monoclonal antibodies in COVID‐19‐related clinical trials

| Intervention | No. of Trials | Target | Size | Comparator | Phase | Randomized/blinded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab a | 1 | TNF alfa | 60 | Standard of care | 2/3 | Yes/No |

| Meplazumab | 1 | CD‐147 | 20 | Single arm | ½ | No/No |

| Sarilumab | 14 | IL‐6R | 400 | Placebo | 2/3 | Yes/Yes |

| Eculizumab | 3 | C5 | 120 | Standard of care | 2 | Yes/No |

| Ixekizumab + AV | 1 | IL‐17A | 40 | AV | 2 | Yes/Yes |

| Nivolumab | 1 | PD‐1 | 15 | Standard of care | 2 | No/No |

| Siltuximab | 1 | IL‐6 | 100 | Corticosteroids | 2 | Yes/No |

| Bevacizumab | 4 | VEGF | 130 | Standard of care | 2 | Yes/No |

| Gimsilumab | 1 | GM‐CSF | 270 | Placebo | 3 | Yes/Yes |

| IFX‐1 | 1 | C5a | 130 | Best supportive care | 2/3 | Yes/No |

| Leronlimab | 1 | CCR5 | 390 | Placebo | 2b/3 | Yes/Yes |

| Lenzilumab | 1 | CSF‐ GM‐CSF | 238 | Placebo | 3 | Yes/Yes |

| Canakinumab | 2 | IL‐1beta | 450 | Placebo | 3 | Yes/Yes |

| Clazakizumab | 2 | IL‐6 | 90 | Placebo | 2 | Yes/Yes |

For monoclonal antibodies under investigation in more than one clinical trial, only one study has been mentioned. For a complete listing, see Ref. 9 and 46.

In association with tocilizumab.

Beside monoclonal antibodies, several other immunosuppressants and immunomodulators are under investigation. 9 Interferon beta‐1a—both intravenously and in an inhaled formulation—interferon alfa‐2a, and peginterferon lambda‐1a are object of 31 clinical studies. Immunoglobulin and convalescent plasma‐based therapy are investigated in 60 trials.

Twenty‐three registered studies 9 are evaluating the use of systemic corticosteroids in COVID‐19. Despite concern about possible detrimental effects, 10 , 11 there is yet no evidence for or against their use in COVID‐19 patients. There is rational to speculate that their safety and efficacy may be different in the early viral phase compared to the late inflammatory phase. Conversely, there is no evidence to withdraw an ongoing treatment with inhaled steroids in subjects with asthma and rhinitis. 12 , 13

Other immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive drugs and the effect of cytokine filtration devices are also under investigation, particularly in COVID‐19 subjects with pneumonia and a severe inflammatory disease. 8

More studies on anti‐TNF drugs have been recommended. 14 Among cell‐based therapies, 24 studies plan to investigate the immunomodulatory role of mesenchymal stem cells. 8

However, despite this intense clinical research and236 papers (including 4 systematic reviews) on COVID‐19 treatment listed by PubMed, evidence available for safe and effective drugs has not progressed at the same speed of the pandemic. 15 In fact, to our knowledge only very few clinical trials have been published.

The randomized, open‐label trial with lopinavir/ritonavir in 199 patients with severe COVID‐19 failed to meet the primary end‐point (time to clinical improvement). 16 However, 70 additional studies are investigating the efficacy of lopinavir/ritonavir in various severity stages of the disease. 9

Following the more promising results of a cohort study of patients treated with remdesivir on a compassionate use, 17 both FDA and EMA have permitted the use of this drug in COVID‐19 clinical trials. While a randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial could not confirm a significant benefit of remdesivir in a cohort of 236 patients—possibly because of the failure to recruit its target of 453 patients 18 —it has been recently anticipated that a larger multi‐center trial in over 1000 subjects showed a high significant (<0.001) effect on the primary outcome of the study (ie, time to recovery, which was reduced from 15 to 11 days). 19 Eleven more trials on remdesivir are still ongoing. 9 A few additional published studies with hydroxichloroquine vs best supportive care, favipiravir vs umifenovir, and lopinavir/ritonavir vs umifenovir are reported by Thorlund and co‐workers. 20

3. COVID‐19 REGISTRIES AND DRUG PIPELINE

However, clinical research is rapidly expanding and hundreds of clinical trials have been registered including, beside immunologic drugs, antiviral drugs, protein kinase inhibitors, anti‐inflammatory drugs, or drugs aimed at facing the most severe symptoms of COVID‐19, such as anti‐coagulants, anti‐infective drugs, and drugs for the cardiovascular, respiratory, and nervous systems (Table 2).

Table 2.

Other nonimmunologic candidate drugs for COVID‐19

| Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine (147) |

| Anti‐viral drugs |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir (70) |

| Favipiravir (24) |

| Umifenovir (15) |

| Remdesivir (11) |

| Sofosbuvir (1) |

| Darunavir (1) |

| Ritonavir (1) |

| Oseltamivir (1) |

| Protein kinase inhibitors |

| Ruxoltinib (13) |

| Baricitinib (5) |

| Imatinib (2) |

| Anti‐infective agents |

| Azytromicin (55) |

| Anticoagulants |

| Enoxaparin (5) |

| Anti‐inflammatory drugs |

In brackets No. of ongoing trials. Data from Ref. 9 to 46.

The WHO registry 21 (ICTRP) included, at April 29, 1524 studies, whose details are not easily accessible. The registry, due to the heavy traffic generated by the COVID‐19 outbreak, is temporarily not accessible from outside the WHO.

US NIH ClinicalTrials.gov 22 lists 1409 trials, including 830 interventional studies; only 20 of these trials have been completed, but results have not been published yet.

Eudra CT 23 includes 175 clinical trials, all still ongoing.

Cytel, a Global Coronavirus COVID‐19 clinical trials tracker, funded, in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 9 lists 1029 clinical trials, 340 from China and 51 dealing with traditional Chinese medicinal products. Most interventional studies evaluate the effects of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine (218 studies), lopinavir/ritonavir (70studies), plasma‐based therapy (60 studies), and tocilizumab (39studies). Only 8 studies are already completed with results (7 from China and 1 from France), but only one has a randomized double‐blind study design.

The comparative review of registries allows some critical considerations.

There is a substantial discrepancy in the number of studies reported in different registries, and it is quite difficult to identify duplicates among registries or studies listed in some registries but not in others.

Furthermore, the available information for individual studies differs from registry to registry and is not easily extractable. At last, protocols of studies are not accessible in most registries. Thus, it is highly appreciable the initiative of tracking and collating clinical trials in a single registry, also using artificial intelligence‐based methods for data search and aggregator services. 20 This approach will allow easier data sharing among investigators and analysis of pooled data.

Data sharing and secondary analysis represent valuable tools to advance knowledge and help regulatory decisions. Transparency policies have been recently adopted in Europe by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) 24 in line with the new EU Clinical Trial Regulation. 25 Data sharing is also recommended by several international institutions 26 and by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. 27 Data sharing appears fundamental in health emergencies, such as COVID‐19 outbreak, to implement rapid and effective responses. Several platforms are available for data storage and analysis also offering protocol assistance and free anonymization of data from subjects with COVID‐19. 28

4. THE NEED FOR A STANDARDIZED APPROACH IN COVID‐19 CLINICAL RESEARCH

However, in order to make feasible secondary analysis of individual studies, these should follow guidelines for standard protocols and minimal requirements for outcome measures such as the Standard Protocol Items Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 29 and the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative. 30

In fact, the major criticism emerging from a review of the ongoing trials is the heterogeneity of protocols. Following the decision of both FDA and EMA, respectively, to allow the use of chloroquine or hydroxichloroquine and remdesivir for clinical trials in COVID‐19, 31 , 32 several small trials have started using these drugs on a compassionate basis. The EMA has expressed concern for these small studies and the compassionate‐use programs across Europe, as they are unlikely to produce the required level of evidence of efficacy and safety of investigational drugs. On the contrary, the EMA strongly recommends that a more coordinated approach and efforts are put in place to prioritize large multi‐country randomized trials and multi‐arm clinical trials investigating different agents simultaneously. 33 In order to generate robust evidence on efficacy and safety of drugs and vaccines for COVID‐19, EMA offers free scientific advice on the best methods and designs to be used in clinical trials. 34

Unarguably, high‐quality clinical trials cannot be easily performed in the setting of an outbreak, when investigators are often asked to make patients’ care a priority. Nonetheless, even if adapted to this challenging context, high‐quality research is still needed. 35 Accordingly, a more standardized approach to clinical research on COVID‐19 should be warranted, including a rigorous but realistic study design, a well‐characterized study population stratified on the basis of age and severity of the disease, a rationale behind the use of the investigational drug and the choice of comparator, and optimal minimal primary outcome(s).

With regard to the study design, while masking might be difficult in studies of COVID‐19, randomization should be mandatory. Multi‐center trials are highly advisable provided that standard operational procedures are set out. Adaptive designs might be considered, and the setting should be specified. Rules for informed consent must adapt to the chosen population. Centralized Ethics Committees or IRBs might favor a more rapid start of the trial. Investigators should be encouraged to publish the study protocol to be drafted according to the SPIRIT 29 and COS‐STAP statement. 36

Age, gender, ethnicity, previous diseases, and undergoing treatments of the selected population have been reported to influence the incidence of COVID‐19. 3 , 4 , 37 , 38 , 39 Demographic and history data should be obtained, possibly through a standard questionnaire, along with other patients’ characteristics such as social status and environmental exposure.

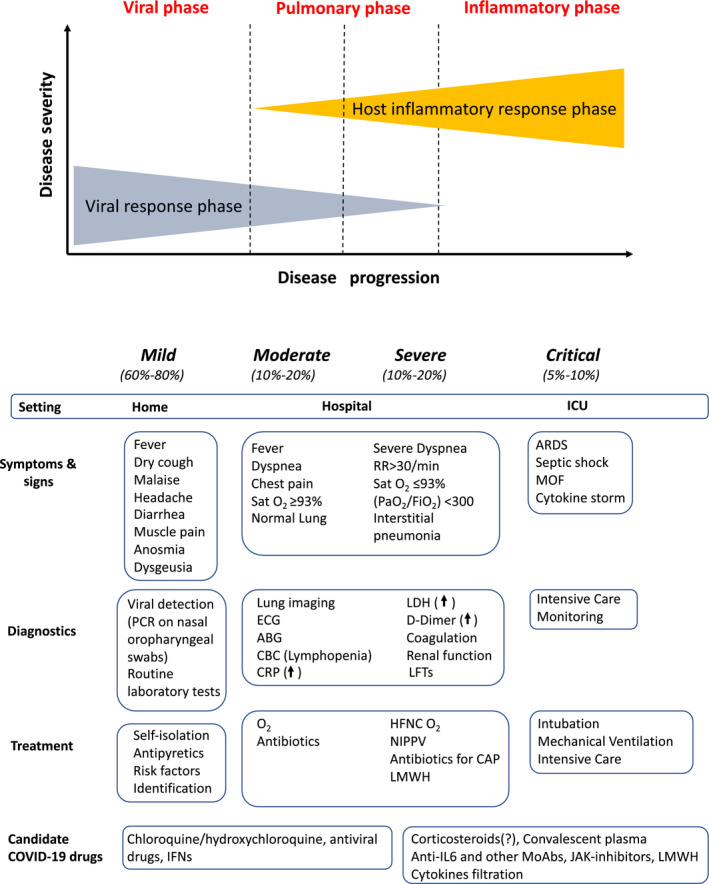

While waiting for a consensus on criteria for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 and a classification of the disease, patients should be stratified on the basis of the study setting, severity, and the predominant pathophysiological abnormality in different phases of the disease (viral, pulmonary, and inflammatory; Figure 1). 40

Figure 1.

Staging of COVID‐19. Clinical features, management, and candidate therapeutic options. Modified from Ref. 40 and 47. Legenda: ABG, arterial blood gas; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAP, community‐acquired pneumonia; CBC, complete blood count; CRP, C‐reactive protein; HFNC, high‐flow nasal cannula; ICU, intensive care unit; LFTs, liver function tests; LMWH, low molecular weight heparins; MOF, multi‐organ failure; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells; NIPPV, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation; PaO2/FiO2, ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2, in mm Hg) to fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2, expressed as a fraction); PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RR, respiratory rate; SatO2, oxygen saturation

Several research groups are working on a variety of preventive and therapeutic interventions. However, despite the accelerated development pathways adopted by many regulatory bodies, 41 the marketing authorization pathway for new drugs is a long process, with a high attrition rate. Therefore, there has been considerable interest in repurposing existing drugs—such as antiviral and immunosuppressant agents—for use in COVID‐19. 8 Studies with these drugs should keep in consideration the putative mechanisms of action of the investigational drug in relation to the different phases of COVID‐19. Antiviral agents, for example, should be used during the early viral phase of the disease while immunosuppressant may be promising candidate drugs in the severe inflammatory phase (while they might dampen the immune response if used early on 15 ). Combination or sequential treatment might also be considered.

An interesting alternative strategy for drugs repurposing in COVID‐19 is represented by a structural analysis of available medicines with potential inhibitory effects on molecules involved in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and replication. 1 , 2 In an in silico molecular modelling, screening of 2000 FDA‐approved drugs for potential inhibitory effect on SARS‐CoV‐2 main protease enzyme (Mpro), the top hits bound to the central site of Mpro substrate‐binding pocket included antiviral drugs such as darunavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir. Interestingly, the top hits bound to the terminal site of Mpro substrate‐binding pocket included montelukast and fexofenadine. 42 Independently from the practical impact of the above observation, this strategy appears promising in repositioning available drugs, until novel targeted treatments for COVID‐19 are available.

Standard of care seems to be a more realistic comparator than placebo, in view of the emergency nature of the epidemic.

Collaborative trials and multi‐arm studies comparing different drugs should also be considered. A commendable example of this kind of approach is represented by the Solidarity clinical trial launched by the WHO. 43 The Solidarity trial is a randomized multi‐countries open‐label trial which compares the efficacy of four treatment options (remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon beta‐1a, and chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine) against standard of care in hospitalized adult patients with COVID‐19. Underlying conditions are recorded and severity of illness at entry is determined by a reduced set of end‐points that can be recorded even in overwhelmed hospitals. Clinically relevant outcomes undergo an interim analysis by an independent Global Data and Safety Monitoring Committee. The simplicity of the trial is balanced by the thousands of patients that are expected to be recruited in more than 70 countries. Preliminary results of this trial are expected by June 2020.

In more rigorous study designs, primary outcome measures should be chosen in relation to the phase of the disease and the drug under investigation. While SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA clearance and the effects on the progression of the disease may represent significant outcome measures for antivirals in the mild forms of the disease, hard end‐points such survival/death are advisable in the most severe forms. However, a core outcome standard set is urgently needed to define a minimal set of outcome measures relevant to patients, investigators, and regulators. 44

5. CONCLUSIONS

Hopefully, the efforts of clinical researchers in the fight against the SARS‐CoV‐2 will result into the identification of effective treatments. This would largely counterbalance the delaying effects of COVID‐19 on ongoing trials for other diseases. 45 However, these efforts might be negatively affected in the absence of guidelines for a more harmonized clinical research and a united commitment of the scientific community to share personal knowledge and data. Allergists and clinical immunologists should have a leading role in this unprecedented challenge.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Bonini S, Maltese G. COVID‐19 Clinical trials: Quality matters more than quantity. Allergy. 2020;75:2542–2547. 10.1111/all.14409

REFERENCES

- 1. Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS‐CoV‐2 by full‐length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444‐1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, et al. Structure of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike receptor‐binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581(7807):215‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang J‐J, Dong X, Cao Y‐Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020. Jul;75(7):1730‐1741. 10.1111/all.14238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/mainpage.aspx. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 6. Ferguson NMLD, Nedjati‐Gilani G, Imai N, et al.College COVID‐19 Response Team. Impact of non‐pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID‐ 19 mortality and healthcare demand. 2020. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperialcollege/medicine/sph/ide/gida‐fellowships/Imperial‐College‐COVID19‐NPI‐modelling‐16‐03‐2020.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 7. Tay MZ, Poh CM, Renia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of Covid‐ 19: immunity, inflammation, intervention. Nature Rev Immunol. 2020;20:363–374. 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lythgoe MP, Middleton P. Ongoing clinical trials for the management of COVID‐19 pandemic. Trend in Pharmacol Sci. 2020;20:363–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.covid19‐trials.com/. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 10. Yang Z, Liu J, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Zhao Q, Liu J. The effect of corticosteroid treatment on patients with coronavirus infection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Infect. 2020. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.062. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Russell B, Moss C, Rigg A, Van Hemerlijck M. COVID‐19 and treatment with NSAIDs and corticiosteroids: should we limit their use in clinical setting? Ecancer. 2020;14:1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halpin DMG, Singh D, Hadfield RM. Inhaled corticosteroids and COVID‐19: a systematic review and clinical perspective. Eur Resp J. 2020;55(5):2001009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bousquet J, Akdis C, Jutel M, et al. Intranasal corticosteroids in allergic rhinitis in COVID‐19 infected patients: an ARIA‐EAACI statement. Allergy. 2020;75:2440‐2444. 10.1111/all.14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feldman M, Maini RN, Woody JN, et al. Trials of anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapy for COVID‐19 are urgently needed. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1407‐1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mullard A. Flooded by the torrent: the COVID‐19 drug pipeline. Lancet. 2020;395:1245‐1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir‐ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787‐1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, et al. Compassionate use of Remdesivir for patients with severe COVID‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID‐ 19: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41591‐020‐00016‐y. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 20. Thorlund K, Dron L, Park J, Hsu G, Forrest JI, Mills EJ. A real‐time dashboard of clinical trials for COVID‐19. Lancet. 2020;2(6):e286‐e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. https://www.who.int/ictrp/en/. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 22. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=COVID&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 23. http://clinicaltrialregister.eu/ctr‐search/search?query=COVID‐19. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 24. Bonini S, Eichler HG, Wathion N, Rasi G. Transparency and the European medicines agency–sharing of clinical trial data. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2452‐2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Regulation (EU) no. 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC. Official Journal of the European Union. 2014.

- 26. Sim I, Stebbins M, Bierer B, et al. Time for NIH to lead on data sharing ‐A draft policy is generally supportive but should start mandating data sharing. Science. 2020;367:1308‐1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C, et al. Sharing clinical trial data: a proposal from the international committee of medical journal editors. N Z Med J. 2016;129(1429):7‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. www.vivli.org. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 29. https://www.spirit‐statement.org/. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 30. http://www.cometinitiative.org/Resources. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 31. Rome BN, Avorn J. Drug evaluation during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med Drug evaluation during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. 2020. 10.1056/NEJMp2009457. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema‐provides‐recommendations‐compassionate‐use‐remdesivir‐covid‐19. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 33. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/call‐pool‐eu‐research‐resources‐large‐scale‐multi‐centre‐multi‐arm‐clinical‐trials‐against‐covid‐19_en.pdf

- 34. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol10/guidanceclinicaltrials_covid19en.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 35. London AJ, Kimmelman J. Against pandemic research exceptionalism. Science. 2020;368(6490):476‐477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome set‐STAndardised protocol items: the COS‐STAP statement. Trials. 2019;20(1):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID‐19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID‐19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8(4):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Salomon SD. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1653‐1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID‐19 Illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical‐therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020; 39(5): 405‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema‐establishes‐task‐force‐take‐quick‐coordinated‐regulatory‐action‐related‐covid‐19‐medicines. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 42. Farag A, Wang P, Ahmed M, Sadek H. Identification of FDA approved drugs targeting COVID‐19 virus by structure‐based drug repositioning. Version 2. Chemrxiv. 2020. 10.26434/chemrxiv.12003930.v2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/global‐research‐on‐novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov/solidarity‐clinical‐trial‐for‐covid‐19‐treatments. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 44. Kirkham JJ, Davis K, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome set‐STAndards for development: the COS‐STAD recommendations. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol‐10/guidanceclinicaltrials_covid19_en.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 46. https://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/da/nyheder/temaer/ny‐coronavirus‐covid‐19/~/media/5B83D25935DF43A38FF823E24604AC36.ash. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 47. https://covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/introduction/. Accessed May 14, 2020.