Abstract

Background: The association between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and the risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has yet to be investigated; thus, we conducted this nationwide cohort study to examine the association in patients from Taiwan. Methods: A total of approximately 2669 individuals with newly diagnosed H. pylori infection and 10,676 age- and sex-matched patients without a diagnosis of H. pylori infection from 2000 to 2013 were identified from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to determine the cumulative incidence of H. pylori infection in each cohort. Whether the patient underwent H. pylori eradication therapy was also determined. Results: The cumulative incidence of IBS was higher in the H. pylori-infected cohort than in the comparison cohort (log-rank test, p < 0.001). After adjustment for potential confounders, H. pylori infection was associated with a significantly increased risk of IBS (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 3.108, p < 0.001). In addition, the H. pylori-infected cohort who did not receive eradication therapy had a higher risk of IBS than the non-H. pylori-infected cohort (adjusted HR 4.16, p < 0.001). The H. pylori-infected cohort who received eradication therapy had a lower risk of IBS than the comparison cohort (adjusted HR 0.464, p = 0.037). Conclusions: Based on a retrospective follow-up, nationwide study in Taiwan, H. pylori infection was associated with an increased risk of IBS; however, aggressive H. pylori infection eradication therapy can also reduce the risk of IBS. Further underlying biological mechanistic research is needed.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori infection (H. pylori infection), National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), retrospective cohort study

1. Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract, is formalized in the Rome criteria, which include chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits [1]. IBS is the most frequently diagnosed GI disorder [2] and the prevalence of IBS worldwide is 10% to 15% of the population [3]. In Taiwan, the prevalence of IBS (2003) was 22.1% according to the Rome II criteria, and no sex difference was found between subjects with and without IBS [4].

The pathophysiology of IBS is multifactorial and remains uncertain [5]. Recently, several studies have proposed new hypotheses of IBS pathophysiology, including genetics, psychosocial dysfunction (brain-gut axis dysfunction) and inflammation [6,7,8,9]. Based on the inflammation hypothesis, epithelial cells of the inflamed intestinal mucosa are more permeable and lead to fluid leakage into the intestine. Compared with non-IBS subjects, IBS subjects have increased mast cells, lymphocytes, TNF alpha, IL-6, LIF, NGF, and IL-1 beta in the intestinal mucosa [9]. Therefore, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection has a potential pathogenic role in IBS given the significant overlaps between IBS and dyspepsia [10]. Approximately more than half of the world’s population is estimated to be infected with H. pylori, which is a widespread gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the human gut [11]. H. pylori infection irritates immune neutrophils and lymphocytes in gut epithelial cells and liberates cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNF-α and IFN-γ [12,13]. Some studies have highlighted an increase in H. pylori infection rates in patients with IBS compared to healthy groups [14,15]. However, other studies have disputed this finding and found no association between H. pylori infection and IBS [16,17]. The inconsistent results were considered to be due to IBS caused by the interaction of multiple factors. Despite multiple investigations, data are conflicting, and no abnormality has been found to be specific for this disorder. Current evidence does not support an association between H. pylori infection and IBS [16]. Therefore, we used the randomized longitudinal health insurance dataset (LHID) selected from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to find IBS in the H. pylori-infected population in Taiwan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

In 1995, the government of Taiwan implemented a single-payer universal health insurance system, the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program, which covers more than 99% of the 23 million residents in Taiwan and has been widely used in academic studies [18]. The NHIRD contains comprehensive, high-quality information, including epidemiological research, and information on diagnoses, prescription use, and health-care information, including inpatient/ambulatory claims, prescription claims, demographic data and hospitalization [19,20,21]. Data for our cohort study were obtained from the NHIRD, which has multiple data sources, is a powerful research engine with enriched dimensions and serves as a guiding light for real-world evidence-based medicine in Taiwan [22]. The International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) was used to define the diagnostic codes.

2.2. Sample Participants

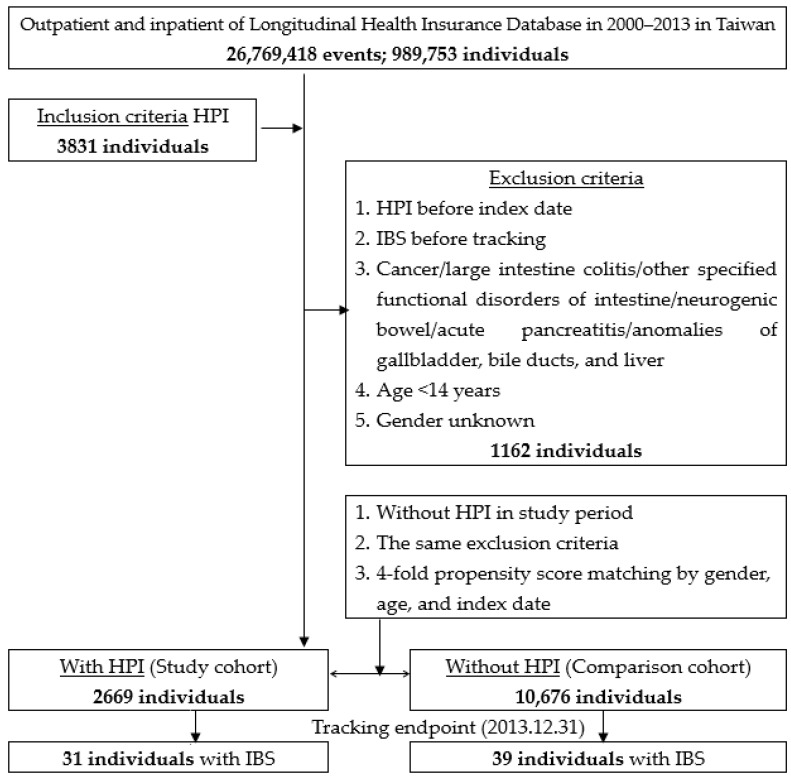

As shown in Figure 1, we identified patients aged 14 years or older with a newly diagnosed H. pylori infection (ICD-9-CM codes 041.86) in the period from 2000 to 2013. The ICD-9-CM diagnosis of H. pylori infection was based on endoscopic biopsy urease testing or non-invasive tests, such as urea breath testing. The diagnosis of H. pylori infection was confirmed at least twice. H. pylori infection is usually treated with triple eradication therapy (amoxicillin/metronidazole, levofloxacin/clarithromycin and a proton pump inhibitor) for at least two weeks to help prevent the bacteria from developing resistance to one particular antibiotic. Those with a documented H. pylori infection before 1 January 2000 or with incomplete medical information were excluded to ensure the data were from individuals with a first diagnosis of H. pylori infection. In Taiwan, the diagnoses of IBS (ICD-9-CM code: 564. 1) were made by board-certified gastroenterologists, and were diagnosed according to the serial versions of the Rome criteria [23]. The NHI administration randomly reviews the records of 1 in 100 ambulatory care visits and 1 in 15 inpatient claims to verify the accuracy of the diagnosis [24]. We also excluded people with a history of IBS. The comparison cohort consisted of patients randomly selected from the patient database without a history of H. pylori infection. For each identified patient with H. pylori infection, four comparison patients were randomly identified and frequency-matched according to the age, sex, and year of index date for the non-H. pylori-infected cohort.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the study sample selection from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. HPI: Helicobacter pylori infection.

2.3. Variables of Interest

The sociodemographic variables used in this study comprised age, sex and urbanization level. The level of urbanization was divided into four levels (Level 1 is the most urbanized and level 4 is the least urbanized) based on the NHRID report. We defined baseline comorbidities, coronary artery disease (ICD-9-CM codes 410-414), cerebrovascular accident (ICD-9-CM codes 430-438), hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401-405), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM codes 272), diabetes (ICD-9-CM codes 250), end-stage renal disease (ICD-9-CM codes 585.6), asthma (ICD-9-CM codes 493) and medication use of tetracycline (drug codes: AC04963100, AC049631G0, AC12059100, AC12639100, AC15791100, AC157911G0, AC22572100, AC225721G0), minocycline (drug codes: A032761100, A033214100, A035969100, A036813100, A043111100, AB40644100, AC33471100, AC35868100, AC36266100, AC36281100, AC36667100, AC36815100, AC36940100, AC38761100, AC39074100, AC39600100) and doxycycline (drug codes: A009397100, AC07233100, AC12782100, AC16227100, AC19254100, AC192541G0, AC23648100, AC236481G0, AC24085100, AC31219100, AC34900100, AC35692100, AC356921G0).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The distribution of sociodemographic data and comorbidities were compared between the Helicobacter pylori infection (HPI) cohort and the comparison cohort using the chi-squared test to examine categorical variables and the t-test to examine continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to estimate IBS in these two cohorts, and the log-rank test examined the difference between the curves. We computed the incidence density rate of IBS (per 100,000 person-years) at follow-up for each cohort. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportion hazard regression models were used to examine the effect of HPI on the risk of IBS, shown as a hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, urbanization level and all comorbidities. Further analysis was performed to assess the effect of the dose response of H. pylori infection to the antibiotic medicine that was prescribed on the risk of IBS. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The comparisons used the significance level of 0.05 for two-sided testing.

2.5. Data Availability

Data are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) published by the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Administration. Due to legal restrictions imposed by the government of Taiwan in relation to the “Personal Information Protection Act”, data cannot be made publicly available. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD (http://www.mohw.gov.tw/cht/DOS/DM1.aspx?f_list_no=812).

2.6. Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGH IRB No. 2-105-05-082; Taipei, Taiwan).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of both cohorts. The mean age was 57.71 ± 17.01 years in the study cohort and 57.70 ± 18.40 years in the control cohort. The difference was not significant (p = 0.593). In addition, there was no significant difference in sex or age for both groups. Regarding insurance premiums (in New Taiwan dollars (NT$)) in both cohorts, almost all of the enrolled patients were in the <18,000 group (98.25%), followed by the 18,000 to 34,999 group (1.44%) and the >35,000 group (0.31%). There was no significant difference in the insurance premiums (NT$) in either group (p = 0.136). In terms of the comorbidity, patients with H. pylori infection had lower rates of coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus (DM) and asthma than the control patients. The CCI_R value was 1.27 ± 0.77 in the study cohort and 0.27 ± 0.69 in the control cohort (p < 0.001). In addition, more individuals in the study cohort than in the control cohort lived in southern and eastern Taiwan and lower urbanized areas, and received therapy in local hospitals (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at the baseline.

| HPI | Total | With | Without | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 13,345 | 2669 | 20.00 | 10,676 | 80.00 | ||

| Gender | 0.999 | ||||||

| Male | 8790 | 65.87 | 1758 | 65.87 | 7032 | 65.87 | |

| Female | 4555 | 34.13 | 911 | 34.13 | 3644 | 34.13 | |

| Age (years) | 57.54 ± 18.13 | 57.71 ± 17.01 | 57.70 ± 18.40 | 0.593 | |||

| Age group (years) | 0.999 | ||||||

| <44 | 3350 | 25.10 | 670 | 25.10 | 2680 | 25.10 | |

| 44–64 | 4715 | 35.33 | 943 | 35.33 | 3772 | 35.33 | |

| ≧65 | 5280 | 39.57 | 1056 | 39.57 | 4224 | 39.57 | |

| Insured premium (NT$) | 0.136 | ||||||

| <18,000 | 13,111 | 98.25 | 2613 | 97.90 | 10,498 | 98.33 | |

| 18,000–34,999 | 192 | 1.44 | 49 | 1.84 | 143 | 1.34 | |

| ≧35,000 | 42 | 0.31 | 7 | 0.26 | 35 | 0.33 | |

| CAD | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 12,087 | 90.57 | 2508 | 93.97 | 9579 | 89.72 | |

| With | 1258 | 9.43 | 161 | 6.03 | 1097 | 10.28 | |

| CVA | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 12,312 | 92.26 | 2583 | 96.78 | 9729 | 91.13 | |

| With | 1033 | 7.74 | 86 | 3.22 | 947 | 8.87 | |

| HTN | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 10,738 | 80.46 | 2247 | 84.19 | 8491 | 79.53 | |

| With | 2607 | 19.54 | 422 | 15.81 | 2185 | 20.47 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 12,904 | 96.70 | 2609 | 97.75 | 10,295 | 96.43 | |

| With | 441 | 3.30 | 60 | 2.25 | 381 | 3.57 | |

| DM | 0.031 | ||||||

| Without | 11,238 | 84.21 | 2284 | 85.58 | 8954 | 83.87 | |

| With | 2107 | 15.79 | 385 | 14.42 | 1722 | 16.13 | |

| ESRD | - | ||||||

| Without | 13,345 | 100.00 | 2669 | 100.00 | 10,676 | 100.00 | |

| With | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Asthma | 0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 13,098 | 98.15 | 2640 | 98.91 | 10,458 | 97.96 | |

| With | 247 | 1.85 | 29 | 1.09 | 218 | 2.04 | |

| CCI_R | 0.47 ± 0.81 | 1.27 ± 0.77 | 0.27 ± 0.69 | <0.001 | |||

| Season | <0.001 | ||||||

| Spring (Mar–May) | 3466 | 25.97 | 628 | 23.53 | 2838 | 26.58 | |

| Summer (Jun–Aug) | 3264 | 24.46 | 674 | 25.25 | 2590 | 24.26 | |

| Autumn (Sep–Nov) | 3019 | 22.62 | 696 | 26.08 | 2323 | 21.76 | |

| Winter (Dec–Feb) | 3596 | 26.95 | 671 | 25.14 | 2925 | 27.40 | |

| Location | <0.001 | ||||||

| Northern Taiwan | 4850 | 36.34 | 835 | 31.29 | 4015 | 37.61 | |

| Middle Taiwan | 3674 | 27.53 | 462 | 17.31 | 3212 | 30.09 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 3744 | 28.06 | 1,005 | 37.65 | 2739 | 25.66 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 1014 | 7.60 | 366 | 13.71 | 648 | 6.07 | |

| Outlets islands | 63 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.04 | 62 | 0.58 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 4030 | 30.20 | 762 | 28.55 | 3268 | 30.61 | |

| 2 | 5998 | 44.95 | 1328 | 49.76 | 4670 | 43.74 | |

| 3 | 1202 | 9.01 | 360 | 13.49 | 842 | 7.89 | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 2115 | 15.85 | 219 | 8.21 | 1896 | 17.76 | |

| Level of care | <0.001 | ||||||

| Hospital center | 4019 | 30.12 | 685 | 25.67 | 3334 | 31.23 | |

| Regional hospital | 5786 | 43.36 | 1374 | 51.48 | 4412 | 41.33 | |

| Local hospital | 3540 | 26.53 | 610 | 22.86 | 2930 | 27.44 | |

P: Chi-square/Fisher exact test on category variables and t-test on continue variables. HPI: Helicobacter pylori infection; NT$: New Taiwan dollar; CAD: coronary artery disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; HTN: hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; ESRD: end-stage renal disease; CCI_R: Charlson comorbidity index removed coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, and asthma.

The IBS rate was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method (Figure 2). The results showed that the study cohort had a significantly higher IBS rate than the control cohort (log-rank test (p < 0.001)). Table 2 shows the Cox regression analysis of the risk factors for IBS. After adjusting for H. pylori infection, sex, age group, insurance premium and pre-existing comorbidities, including sleep apnea, HTN, and only H. pylori infection (aHR = 3.108, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.934–4.995, p < 0.001), patients in the study cohort showed an increased risk of IBS diagnosis compared with the control cohort. In addition, patients with CVA had a decreased risk of developing IBS than those without CVA (aHR = 3.121, p < 0.001). Patients with other comorbidities, age groups and insurance premiums, as well as other chronic diseases, were not significantly associated with IBS diagnosis according to the hazard ratios (all p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier for cumulative risk of IBS in patients aged 14 and over stratified by Helicobacter pylori infection (HPI) with the log-rank test. Without HPI vs. With HPI, without medication: Log-rank P < 0.001. Without HPI vs. With HPI, with medication: Log-rank P = 0.479. With HPI, without medication vs. With HPI, with medication: Log-rank P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Factors of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) by using Cox regression.

| Variables | Crude HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPI | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 2.887 | 1.801 | 4.626 | <0.001 | 3.108 | 1.934 | 4.995 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.873 | 0.539 | 1.412 | 0.579 | 1.075 | 0.474 | 1.268 | 0.310 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| <44 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 44–64 | 0.877 | 0.457 | 1.683 | 0.693 | 1.112 | 0.566 | 2.187 | 0.757 |

| ≧65 | 0.700 | 0.378 | 1.295 | 0.256 | 0.817 | 0.416 | 1.605 | 0.557 |

| Insured premium (NT$) | ||||||||

| <18,000 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 18,000–34,999 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.507 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.966 |

| ≧35,000 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.777 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.987 |

| CAD | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.994 | 0.409 | 1.952 | 0.778 | 1.194 | 0.535 | 2.663 | 0.665 |

| CVA | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 2.279 | 1.268 | 4.094 | 0.006 | 3.121 | 1.670 | 5.834 | <0.001 |

| HTN | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.537 | 0.298 | 2.094 | 0.285 | 1.552 | 0.286 | 2.065 | 0.077 |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.042 | 0.506 | 2.894 | 0.366 | 1.048 | 0.561 | 3.317 | 0.432 |

| DM | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.462 | 0.921 | 2.965 | 0.054 | 1.488 | 0.729 | 2.042 | 0.064 |

| ESRD | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Asthma | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.475 | 0.361 | 6.018 | 0.588 | 1.809 | 0.433 | 7.550 | 0.416 |

| CCI_R | 0.905 | 0.775 | 1.058 | 0.209 | 1.017 | 0.875 | 1.184 | 0.309 |

| Season | ||||||||

| Spring | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Summer | 2.068 | 0.668 | 2.942 | 0.829 | 2.142 | 0.626 | 2.886 | 0.665 |

| Autumn | 1.532 | 0.573 | 2.037 | 0.064 | 1.543 | 0.578 | 2.147 | 0.074 |

| Winter | 1.389 | 1.175 | 1.864 | 0.020 | 1.413 | 1.186 | 1.919 | 0.030 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Northern Taiwan | Reference | |||||||

| Middle Taiwan | 2.289 | 1.238 | 4.231 | 0.008 | ||||

| Southern Taiwan | 1.532 | 0.788 | 2.980 | 0.209 | ||||

| Eastern Taiwan | 1.893 | 0.779 | 4.605 | 0.159 | ||||

| Outlets islands | 0.000 | - | - | 0.968 | ||||

| Urbanization level | ||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 2.294 | 1.190 | 4.423 | 0.013 | 1.536 | 0.259 | 1.701 | 0.092 |

| 2 | 1.378 | 0.535 | 3.551 | 0.507 | 1.331 | 0.291 | 1.696 | 0.084 |

| 3 | 1.092 | 0.581 | 2.052 | 0.785 | 0.581 | 0.235 | 1.438 | 0.240 |

| 4 (The lowest) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Level of care | ||||||||

| Hospital center | 2.514 | 1.280 | 4.937 | 0.007 | 1.790 | 0.498 | 2.698 | 0.396 |

| Regional hospital | 1.690 | 0.890 | 3.212 | 0.109 | 1.590 | 0.275 | 2.224 | 0.177 |

| Local hospital | Reference | Reference | ||||||

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; HPI: Helicobacter pylori infection; NT$: New Taiwan dollar; CAD: coronary artery disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; HTN: hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; ESRD: end-stage renal disease; CCI_R: Charlson comorbidity index removed coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, and asthma. Adjusted HR: Adjusted variables are listed. P: Chi-square/Fisher exact test on category variables and t-test on continue variables.

In the subgroup analysis comparing patients with and without H. pylori infection (Table 3), the overall incidence of IBS was 109.5 per 100,000 person-years in the study cohort and 33.83 per 100,000 person-years in the control cohort. Female and male H. pylori-infected patients showed an increased risk of developing IBS (total aHR = 3.108, p < 0.001; 3.074 in the corresponding age group of females, p < 0.001; 3.228 in the corresponding age group of males, p = 0.003). In the age group analysis, patients with H. pylori infection in the 44 to 64-year age group were independently associated with an increased risk following IBS diagnosis compared with patients without H. pylori infection (aHR= 4.971, p < 0.001). In the insured premium group analysis, H. pylori-infected patients in the <18,000 group showed an increased risk of developing IBS (aHR = 3.108, p < 0.001). In the pre-existing condition group analysis, H. pylori-infected patients with CAD, CVA, HTN or DM displayed an increased risk of developing IBS (aHR = 3.268, p < 0.001 in CAD; aHR = 3.605, p < 0.001 in CVA; aHR= 4.702, p < 0.001 in HTN; aHR = 15.952, p < 0.001 in DM). In the season group analysis, patients infected with H. pylori in the summer and autumn groups showed an increased risk of developing IBS (aHR = 4.035, p = 0.001 in summer; aHR = 3.594, p = 0.009 in autumn). In the level of care group analysis, H. pylori-infected patients in the hospital center and regional hospital groups displayed an increased risk of developing IBS compared with those in clinics (aHR = 5.402, p = 0.003 in hospital center; aHR = 3.462, p < 0.001 in regional hospital). Patients with H. pylori infection were associated with a higher risk of IBS than patients without H. pylori infection, and patients with H. pylori infection who received aggressive eradication therapy had a decreased risk of IBS compared with patients with H. pylori infection who did not receive eradication therapy (adjusted HR 0.464; 95% CI 0.148–0.963, p = 0.037) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Factors of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) stratified by variables listed in the table by using Cox regression.

| With HPI | Without HPI | With vs. Without | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | PYs | Rate | Event | PYs | Rate | Ratio | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | |

| Total | 31 | 28,376.11 | 109.25 | 39 | 115,278.73 | 33.83 | 3.229 | 3.108 | 1.934 | 4.995 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 19 | 18,081.31 | 105.08 | 24 | 74,553.61 | 32.19 | 3.264 | 3.228 | 1.487 | 7.010 | 0.003 |

| Female | 12 | 10,294.81 | 116.56 | 15 | 40,725.13 | 36.83 | 3.165 | 3.074 | 1.678 | 5.629 | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||

| <44 | 7 | 5265.65 | 132.94 | 8 | 20,134.93 | 39.73 | 3.346 | 3.269 | 1.130 | 9.458 | 0.029 |

| 44–64 | 13 | 8407.04 | 154.63 | 10 | 34,593.43 | 28.91 | 5.349 | 4.971 | 2.148 | 11.503 | <0.001 |

| ≧65 | 11 | 14,703.42 | 74.81 | 21 | 60,550.38 | 34.68 | 2.157 | 2.201 | 1.506 | 4.589 | 0.035 |

| Insured premium (NT$) | |||||||||||

| <18,000 | 31 | 27,747.83 | 111.72 | 39 | 113,542.93 | 34.35 | 3.253 | 3.108 | 1.934 | 4.995 | <0.001 |

| 18,000–34,999 | 0 | 624.29 | 0.00 | 0 | 1380.70 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ≧35,000 | 0 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 355.11 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| CAD | |||||||||||

| Without | 26 | 25,383.09 | 102.43 | 34 | 102,503.61 | 33.17 | 3.088 | 1.654 | 0.246 | 11.141 | 0.605 |

| With | 5 | 2993.02 | 167.06 | 5 | 12,775.13 | 39.14 | 4.268 | 3.268 | 1.986 | 5.378 | <0.001 |

| CVA | |||||||||||

| Without | 22 | 25,674.01 | 85.69 | 29 | 103,869.28 | 27.92 | 3.069 | 2.475 | 1.427 | 5.098 | 0.039 |

| With | 9 | 2702.10 | 333.07 | 10 | 11,409.45 | 87.65 | 3.800 | 3.605 | 2.127 | 6.110 | <0.001 |

| HTN | |||||||||||

| Without | 24 | 20,486.19 | 117.15 | 34 | 83,677.62 | 40.63 | 2.883 | 2.775 | 1.639 | 4.697 | <0.001 |

| With | 7 | 7889.93 | 88.72 | 5 | 31,601.12 | 15.82 | 5.607 | 4.702 | 1.463 | 15.116 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | |||||||||||

| Without | 31 | 27,470.42 | 112.85 | 38 | 111,100.13 | 34.20 | 3.299 | 3.186 | 1.977 | 5.133 | <0.001 |

| With | 0 | 905.70 | 0.00 | 1 | 4178.61 | 23.93 | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.752 |

| DM | |||||||||||

| Without | 25 | 22,236.72 | 112.43 | 37 | 90,656.96 | 40.81 | 2.755 | 2.655 | 1.592 | 4.427 | <0.001 |

| With | 6 | 6139.39 | 97.73 | 2 | 24,621.78 | 8.12 | 12.031 | 15.952 | 2.797 | 90.961 | <0.001 |

| ESRD | |||||||||||

| Without | 31 | 28,376.11 | 109.25 | 39 | 115,278.73 | 33.83 | 3.229 | 3.108 | 1.934 | 4.995 | <0.001 |

| With | 0 | 0.00 | - | 0 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Asthma | |||||||||||

| Without | 30 | 27,885.94 | 107.58 | 38 | 113,027.76 | 33.62 | 3.200 | 3.050 | 1.884 | 4.937 | <0.001 |

| With | 1 | 490.17 | 204.01 | 1 | 2250.98 | 44.43 | 4.592 | 4.497 | 0.009 | 12.589 | 0.747 |

| Season | |||||||||||

| Spring | 7 | 5786.86 | 120.96 | 12 | 24,237.41 | 49.51 | 2.443 | 2.197 | 0.847 | 5.700 | 0.105 |

| Summer | 12 | 6943.36 | 172.83 | 13 | 28,874.00 | 45.02 | 3.839 | 4.035 | 1.809 | 8.999 | 0.001 |

| Autumn | 8 | 9022.10 | 88.67 | 9 | 34,938.86 | 25.76 | 3.442 | 3.594 | 1.367 | 9.447 | 0.009 |

| Winter | 4 | 6623.80 | 60.39 | 5 | 27,228.47 | 18.36 | 3.289 | 2.658 | 0.685 | 10.312 | 0.158 |

| Urbanization level | |||||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 9 | 7304.40 | 123.21 | 6 | 32,885.51 | 18.25 | 6.753 | 6.726 | 2.272 | 19.907 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 13 | 14,376.62 | 90.42 | 14 | 51,741.11 | 27.06 | 3.342 | 3.069 | 1.434 | 6.568 | 0.004 |

| 3 | 2 | 2293.89 | 87.19 | 4 | 9283.94 | 43.09 | 2.024 | 1.936 | 0.336 | 11.480 | 0.453 |

| 4 (The lowest) | 7 | 4401.19 | 159.05 | 15 | 21,368.18 | 70.20 | 2.266 | 1.947 | 0.779 | 4.865 | 0.154 |

| Level of care | |||||||||||

| Hospital center | 7 | 8402.69 | 83.31 | 6 | 36,328.46 | 16.52 | 5.044 | 5.402 | 1.774 | 16.446 | 0.003 |

| Regional hospital | 17 | 13,757.36 | 123.57 | 16 | 52,465.12 | 30.50 | 4.052 | 3..462 | 1.735 | 6.909 | <0.001 |

| Local hospital | 7 | 6216.06 | 112.61 | 17 | 26,485.15 | 64.19 | 1.754 | 1.590 | 0.645 | 3.917 | 0.313 |

PYs: Person-years; Adjusted HR: Adjusted Hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; HPI: Helicobacter pylori infection; CAD: coronary artery disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; HTN: hypertension; DM: diabetes mellitus; ESRD: end-stage renal disease. Adjusted for the variables listed in Table 2.

Table 4.

Factors of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) among study population and PHI cohort by using Cox regression.

| HPI Cohort and Comparison Cohort | HPI Cohort | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Population | Event | PYs | Rate | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

| Without HPI | 39 | 28,376.11 | 137.44 | Reference | |||||||

| With HPI | 31 | 28,376.11 | 109.25 | ||||||||

| without medication | 25 | 16,605.68 | 150.55 | 4.160 | 2.508 | 6.900 | <0.001 | Reference | |||

| with medication | 6 | 11,770.44 | 50.98 | 0.916 | 0.241 | 2.590 | 0.344 | 0.464 | 0.148 | 0.963 | 0.037 |

PYs: Person-years; Adjusted HR: Adjusted Hazard ratio; HPI: Helicobacter pylori infection. Adjusted for the variables listed in Table 2; CI: confidence interval.

4. Discussion

This is the first large-scale, population-based study with long-term follow-up on the association between H. pylori infection and the risk of IBS. After adjusting for covariates, the overall adjusted HR was 3.108 (95% CI: 1.934–4.995, P < 0.001). In other words, adult patients with H. pylori infection had a nearly 3.1-fold increased risk of developing IBS than those without H. pylori infection. The Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that the study subjects had a significantly higher 14-year IBS rate than the controls after adjusting for potential confounders; this is further strong evidence for a potential association between IBS and H. pylori infection.

H. pylori can produce bacterial urease, which hydrolyses in gastric luminal urea to form ammonia, which helps neutralize gastric acid and form a protective cloud around the organism, enabling it to penetrate the gastric mucus layer [25]. Several studies have reported an association between H. pylori infection and the incidence of gastric cancer and colorectal cancer [26,27]. Diagnostic testing for H. pylori includes endoscopic biopsy urease testing, urea breath testing, stool antigen assay, and serological ELISA testing [28]. H. pylori infection is usually treated with at least two different antibiotics at once to help prevent the bacteria from developing resistance to one particular antibiotic [29]. Triple eradication therapy and bismuth quadruple treatment regimens are popular in Taiwan.

The pathogenesis of IBS is still uncertain. In our study, we tried to find a relationship between IBS and H. pylori infection. It seems that chronic inflammation caused by H. pylori infection is related to the pathogenesis of atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and peptic ulcers [30]. H. pylori infection may increase inflammatory marker levels [31], increase mast cell activation, and then affect the gastric mucosa and nerve remodeling [32,33,34], causing visceral hypersensitivity symptoms such as those of IBS [35,36,37,38].

According to our study, patients with H. pylori infection who did not receive eradication therapy had a higher risk of IBS than the non-H. pylori-infected cohort. (adjusted HR 4.16; 95% CI 2.508–6.900). Patients with H. pylori infection who received eradication therapy had a lower risk of IBS than the untreated group (adjusted HR 0.464; 95% CI 0.148–0.963). In the long term observation, the risk of IBS is reduced in the H. pylori infection-treated population. There seems to be some connections between H. pylori infection and IBS. Clinically, it is also possible to add a supplemental H. pylori test for drug treatment to reduce the symptoms of IBS.

The association between IBS and H. pylori has been challenged. For example, H. pylori is thought to commonly influence the upper GI tract rather than the lower GI tract. Additionally, findings by Xiong indicate that there is no relationship between H. pylori infection and IBS [39]. However, although this multi-center retrospective study considered eradication medicine resistance, the cohort was only followed up for one year, and there was no follow-up after second-line drugs were administered. Other data have shown that the association could be fortuitous given the widespread prevalence of H. pylori infection globally [40]. Clinically, H. pylori infection drugs fail or resistance develops in approximately 10% of patients [41], and there are other many reasons for failure. Perhaps our big data research can reduce these factors.

This study has a number of strengths. First, the sample size was very large, which enhanced the statistical power of the data. We used stratified analyses based on the confounding factors of age, comorbidities, and a wide range of demographic characteristics. Second, because we used a nationwide database with a very high coverage rate, almost all patients’ follow-up data were available. Third, the population-based data were considered representative of the general population in Taiwan.

Our study also had some limitations. First, this was a retrospective cohort study; therefore, it has lower statistical quality. Bias from unknown confounders and errors of primary records may have affected our results, and a well-designed prospective, randomized, controlled study is needed to help establish causal relationships. Second, the NHIRD does not report information such as clinical symptoms, signs, or laboratory data, which may help distinguish different types of IBS for further analysis.

5. Conclusions

Patients with H. pylori infection have a higher proportion of IBS, and aggressive H. pylori infection eradication therapy can reduce the risk of IBS. Further underlying biological mechanistic research is needed. Clinically, IBS patients seem to be able to undergo routine H. pylori diagnostic tests to determine the direction of treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation (TSGH-B109010). The sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript. We also appreciate the provision of the National Health Insurance Research Database by the Taiwan Health and Welfare Data Science Center and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (HWDC, MOW).

Author Contributions

J.-M.H., C.-M.L. and W.-C.C. conceived, planned, and conducted this study. J.-M.H., C.-M.L., C.-H.H. and W.-C.C. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. C.-H.C., C.-Y.C., L.-Y.W. and P.-K.C., S.-D.H., Z.-J.H. contributed to this data interpretation. C.-M.L. and J.-M.H. wrote the draft. J.-M.H., C.-H.H. and W.-C.C. conducted the critical revisions of this article. All the authors approved this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Camilleri M., Choi M.G. Irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997;11:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.84256000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Defrees D.N., Bailey J. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Prim. Care. 2017;44:655–671. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman D.A., Camilleri M., Mayer E.A., Whitehead W.E. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu C.L., Chen C.Y., Lang H.C., Luo J.C., Wang S.S., Chang F.Y., Lee S.D. Current patterns of irritable bowel syndrome in Taiwan: The Rome II questionnaire on a Chinese population. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;18:1159–1169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1626–1635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1207068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellini M., Gambaccini D., Stasi C., Urbano M.T., Marchi S., Usai-Satta P. Irritable bowel syndrome: A disease still searching for pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8807–8820. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammed I., Cherkas L.F., Riley S.A., Spector T.D., Trudgill N.J. Genetic influences in irritable bowel syndrome: A twin study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1340–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Oudenhove L., Levy R.L., Crowell M.D., Drossman D.A., Halpert A.D., Keefer L., Lackner J.M., Murphy T.B., Naliboff B.D. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: How central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1355–1367. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanner S.J., Greenwood-Van Meerveld B., Mawe G.M., Shea-Donohue T., Verdu E.F., Wood J., Grundy D. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: Basic science. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1280–1291. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agréus L., Svärdsudd K., Nyrén O., Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: Overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamani M., Ebrahimtabar F., Zamani V., Miller W., Alizadeh-Navaei R., Shokri-Shirvani J., Derakhshan M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;47:868–876. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bamford K.B., Fan X., Crowe S.E., Leary J.F., Gourley W.K., Luthra G.K., Brooks E.G., Graham D.Y., Reyes V.E., Ernst P.B. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:482–492. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattapallil J.J., Dandekar S., Canfield D.R., Solnick J.V. A predominant Th1 type of immune response is induced early during acute Helicobacter pylori infection in rhesus macaques. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:307–315. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelrazak M., Walid F., Abdelrahman M., Mahmoud M. Interrelation between helicobacter pylori infection, infantile colic, and irritable bowel syndrome in pediatric patients. J. Gastrointest Dig. Syst. 2015;25:5702–5710. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y., Chen L. Role of Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Diarrhea-predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Chin. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;22:482–485. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng Q.X., Foo N.X., Loke W., Koh Y.Q., Seah V.J.M., Soh A.Y.S., Yeo W.S. Is there an association between Helicobacter pylori infection and irritable bowel syndrome? A meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5702. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i37.5702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malinen E., Rinttilä T., Kajander K., Mättö J., Kassinen A., Krogius L., Saarela M., Korpela R., Palva A. Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan W.S.H. Taiwan’s healthcare report 2010. EPMA J. 2010;1:563–585. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng C.L., Kao Y.H.Y., Lin S.J., Lee C.H., Lai M.L. Validation of the National Health Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2011;20:236–242. doi: 10.1002/pds.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai M.-N., Wang S.-M., Chen P.-C., Chen Y.-Y., Wang J.-D. Population-based case–control study of Chinese herbal products containing aristolochic acid and urinary tract cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102:179–186. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C.-Y., Chen Y.-J., Ho H.J., Hsu Y.-C., Kuo K.N., Wu M.-S., Lin J.-T. Association between nucleoside analogues and risk of hepatitis B virus–related hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following liver resection. JAMA. 2012;308:1906–1913. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh C.-Y., Su C.-C., Shao S.-C., Sung S.-F., Lin S.-J., Yang Y.-H.K., Lai E.C.-C. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: Past and future. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019;11:349. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S196293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan C.H., Chang C.C., Su C.T., Tsai P.S. Trends in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Incidence among Taiwanese Adults during 2003-2013: A Population-Based Study of Sex and Age Differences. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0166922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Health Insurance Administration National Health Insurance Reimbursement Regulations 2018. [(accessed on 14 March 2018)]; Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=L0060006.

- 25.Mobley H.L.T. The role of Helicobacter pylori urease in the pathogenesis of gastritis and peptic ulceration. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;10:57–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.22164006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y., Chiang T.-H., Chou C.-K., Tu Y., Liao W.-C., Wu M.-S., Graham D.Y. Association Between Helicobacter pylori Eradication and Gastric Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113–1124. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu I.-L., Tsai C.-H., Hsu C.-H., Hu J.-M., Chen Y.-C., Tian Y.-F., You S.-L., Chen C.-Y., Hsiao C.-W., Lin C.-Y., et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of colorectal cancer: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Qjm Int. J. Med. 2019;112:787–792. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcz157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suerbaum S., Michetti P. Helicobacter pyloriInfection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chey W., Leontiadis G.I., Howden C.W., Moss S.F. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowe S.E. Helicobacter infection, chronic inflammation, and the development of malignancy. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2005;21:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson L., Britton J., Lewis S.A., McKeever T., Atherton J., Fullerton D., Fogarty A.W. A Population-Based Epidemiologic Study of Helicobacter Pylori Infection and its Association with Systemic Inflammation. Helicobacter. 2009;14:460–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montemurro P., Nishioka H., Dundon W.G., De Bernard M., Del Giudice G., Rappuoli R., Montecucco C. The neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a potent stimulant of mast cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:671. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<671::AID-IMMU671>3.3.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stead R.H., Hewlett B.R., Lhotak S., Colley E.C.C., Frendo M., Dixon M.F. Do Gastric Mucosal Nerves Remodel in H. pylori Gastritis? Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 1994. pp. 281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Supajatura V., Ushio H., Wada A., Yahiro K., Okumura K., Ogawa H., Hirayama T., Ra C. Cutting edge: VacA, a vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori, directly activates mast cells for migration and production of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2603–2607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerards C., Leodolter A., Glasbrenner B., Malfertheiner P.H. pylori infection and visceral hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Dis. 2001;19:170–173. doi: 10.1159/000050673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Öhman L., Simrén M. Pathogenesis of IBS: Role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao S., Read N., Brown C., Bruce C., Holdsworth C. Studies on the mechanism of bowel disturbance in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:934–940. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanghellini V., Barbara G., De Giorgio R., Tosetti C., Cogliandro R., Cogliandro L., Salvioli B., Corinaldesi R. Helicobacter pylori, mucosal inflammation and symptom perception-new insights into an old hypothesis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;15:28–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiong F., Xiong M., Ma Z., Huang S., Li A., Liu S. Lack of association found between Helicobacter pylori infection and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A multicenter retrospective study. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/3059201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hooi J.K., Lai W.Y., Ng W.K., Suen M.M., Underwood F.E., Tanyingoh D., Malfertheiner P., Graham D.Y., Wong V.W., Wu J.C., et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savoldi A., Carrara E., Graham D.Y., Conti M., Tacconelli E. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis in World Health Organization Regions. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1372–1382. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]