Abstract

Postweaning mortality is extremely complex with a multitude of noninfectious and infectious contributing factors. In the current review, our objective is to describe the current state of knowledge regarding infectious causes of postweaning mortality, focusing on estimates of frequency and magnitude of effect where available. While infectious mortality is often categorized by physiologic body system affected, we believe the complex multifactorial nature is better understood by an alternative stratification dependent on intervention type. This category method subjectively combines disease pathogenesis knowledge, epidemiology, and economic consequences. These intervention categories included depopulation of affected cohorts of animals, elimination protocols using knowledge of immunity and epidemiology, or less aggressive interventions. The most aggressive approach to control infectious etiologies is through herd depopulation and repopulation. Historically, these protocols were successful for Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and swine dysentery among others. Additionally, this aggressive measure likely would be used to minimize disease spread if either a foreign animal disease was introduced or pseudorabies virus was reintroduced into domestic swine populations. Elimination practices have been successful for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, coronaviruses, including transmissible gastroenteritis virus, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, and porcine deltacoronavirus, swine influenza virus, nondysentery Brachyspira spp., and others. Porcine circovirus type 2 can have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality; however, it is often adequately controlled through immunization. Many other infectious etiologies present in swine production have not elicited these aggressive control measures. This may be because less aggressive control measures, such as vaccination, management, and therapeutics, are effective, their impact on mortality or productivity is not great enough to warrant, or there is inadequate understanding to employ control procedures efficaciously and efficiently. Since there are many infectious agents and noninfectious contributors, emphasis should continue to be placed on those infectious agents with the greatest impact to minimize postweaning mortality.

Keywords: death loss, infectious, mortality, postweaning, swine

INTRODUCTION

Postweaning mortality is caused by a complex host of etiologies and risk factors with myriad interactive effects. In an effort to reduce postweaning mortality, contributors must be identified and effective strategies must be generated, evaluated, and implemented. Historically, greater resource allocation has been directed toward preweaning mortality, including research and summary articles, compared with postweaning mortality (Bereskin et al., 1973; Alonso-Spilsbury et al., 2007; Muns et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018). To reduce mortality most effectively, producers and researchers should focus attention on those contributing factors with the greatest magnitude of effect and that can be controlled. We are unaware of any recent literature review, systematic review, or meta-analysis that has been performed regarding postweaning mortality. While causes of infectious mortality are often categorized by physiologic body system affected, we believe the complex multifactorial nature is better understood by an alternative stratification based on the intervention type applied. This category method subjectively combines knowledge of disease pathogenesis, epidemiology, and economic consequences. The proposed intervention categories are depopulation of affected cohorts of animals, elimination protocols using knowledge of immunity and epidemiology, and a third category of less aggressive interventions. This categorization allows simplification of the innumerable interactions between infectious and noninfectious factors contributing to postweaning mortality that are summarized as “the causal web” proposed by Gebhardt et al. (2020). One of the most complex and important interactive effects is the impact of various noninfectious factors on incidence, severity, and resolution of disease. Our objective is to describe the current state of knowledge regarding infectious causes of postweaning mortality, focusing on estimates of frequency, and magnitude of effect where available. The current document will focus on infectious causes of postweaning mortality without describing detailed clinical signs or therapeutic, control, or preventative measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The literature search was performed using Web of Science (https://login.webofknowledge.com/), which incorporated the Web of Science Core Collection, CAB Abstracts, and Medline databases, and Pubmed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), as well as the Scopus (www.scopus.com). Search terms included (SWINE OR PIG) AND (MORTALITY OR MORBIDITY OR DEAD OR REMOVAL) AND the respective search item of interest. Additionally, the assessment of bibliographical items resulted in further identification of relevant sources. Articles were restricted to primarily English language; however, non-English articles that contained an English abstract where relevant information could be extracted were included. Once relevant articles were identified, they were filed and categorized according to topic for further evaluation. This review is based on peer-reviewed literature without including conference proceedings and other nonpeer-reviewed literature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

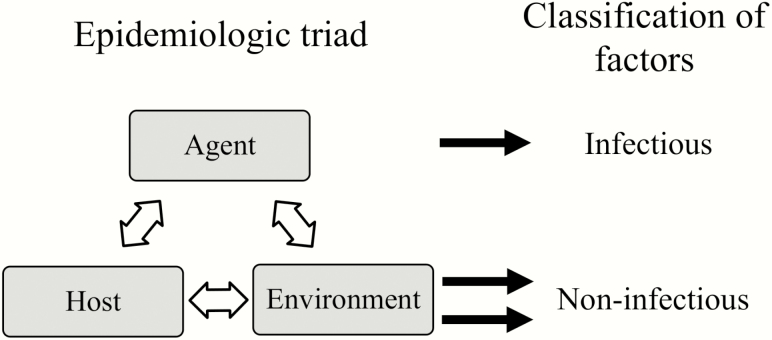

Overview of Infectious Disease

Infectious disease is a common contributing factor to mortality in all growth stages of swine. Mortality categories with the largest proportions include respiratory, gastrointestinal, meningitis/central nervous system signs, and failure to thrive (USDA 2015). Relative measures of incidence and magnitude of effect for infectious causes of postweaning mortality is included in Table 1. Disease is multifactorial in nature, often described as an epidemiologic triad consisting of agent, host, and environment (Dohoo et al., 2003). For the purpose of this endeavor, the epidemiologic triad of determinants of disease can be categorized into infectious and noninfectious factors (Fig. 1). Infectious agents can include viruses, bacteria, parasites, and other agents, such as fungi or prions and are discussed in the current report. Noninfectious factors include characteristics of the host and environment that are discussed in greater detail in the accompanying manuscript. It is critical to understand the interwoven nature of these factors and acknowledge the complexity of biology, physiology, and production outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of infectious factors contributing to postweaning mortality based on incidence and magnitude of potential morbidity and mortalitya

| Approach | Infectious agent | Incidenceb | Magnitudec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive depopulation | |||

| Swine dysenteryd | + | +++ | |

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae | + | ++ | |

| Foreign animal diseasee | − | +++ | |

| Pseudorabies virus | − | +++ | |

| Elimination | |||

| Enzootic pneumoniaf | +++ | ++ | |

| PRRSV | +++ | +++ | |

| Swine influenza virus | +++ | ++ | |

| Nondysentery Brachyspira spp. | ++ | + | |

| Coronavirusesg | ++ | ++ | |

| Infectious agents often managed without depopulation/elimination | |||

| Glasserella parasuis h | ++ | ++ | |

| Pasteurella multocida | ++ | ++ | |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | ++ | + | |

| Other Mycoplasma spp.i | ++ | + | |

| Actinobacillus suis | ++ | + | |

| Lawsonia intracellularis | +++ | ++ | |

| Salmonella spp. | ++ | +++ | |

| Escherichia coli | ++ | ++ | |

| Rotavirus | ++ | ++ | |

| Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome | + | ++ | |

| Streptococcus suis | +++ | ++ | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | +++ | ++ | |

| Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | ++ | ++ | |

| Porcine circovirus | +++ | +++ | |

| Neurological syndromes associated with viral agents | ++ | +++ |

aQualitative assignment of relative incidence and magnitude of mortality was performed by primary author (J.T.G.) based on summarization of published literature.

bRelative incidence of mortality attributed to the infectious agent was denoted using a system ranging from + to +++. Infectious agents not currently in domestic swine populations in the United States was denoted by “−”.

cRelative magnitude of mortality in a population attributed to the presence of the infectious agent was described as + (low potential), ++ (moderate potential), and +++ (significant potential).

dCaused by Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Brachyspira hampsonii, and Brachyspira suanatina.

eIncluding, but not limited to, African swine fever virus, classical swine fever virus, and foot and mouth disease.

fCaused by Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae.

gIncludes PEDV, TGEV, and PDCoV.

hFormerly Haemophilus parasuis.

iIncludes Mycoplasma hyosynoviae, Mycoplasma hyorhinis, and Mycoplasma suis.

Figure 1.

Epidemiologic triad of disease determinants and classification into factors contributing to postweaning mortality.

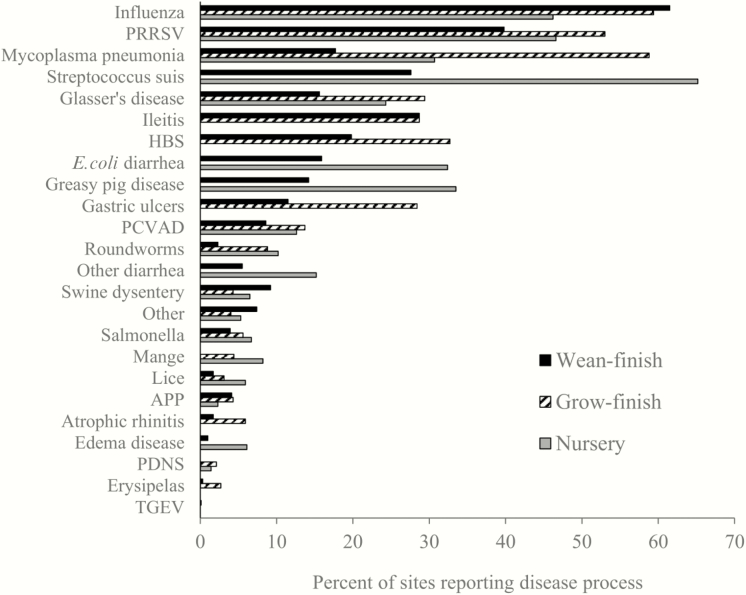

Reported incidence of specific disease processes for nursery, wean-to-finish, and grow-finish sites is provided in Fig. 2 (USDA, 2016). Mortality has been shown to be significantly greater in animals experiencing a high health challenge [porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and swine influenza virus A (IAV); 19.9%)] compared to moderate health challenge (IAV; 7.7%) or low health challenge (no PRRSV or IAV; 3.3%; Cornelison et al., 2018). Such data illustrates the significant impact that the combination of infectious causes of mortality can have on postweaning mortality. Throughout this review, the terminology of commercial swine production and domestic swine are used interchangeably to describe the swine population raised in a controlled, nonferal manner.

Figure 2.

Percentage of nursery, wean-finish, and grow-finish sites reporting specific disease processes in the previous year [adapted from USDA (2016)]. Producer-reported values.

Systems-Based Overview of Infectious Etiologies

One approach to conceptualizing infectious postweaning mortality causes is categorization by physiologic system affected. Major systems affected and associated infectious agents include respiratory (IAV, PRRSV, Mycoplasma spp., and Glasserella parasuis), enteric (Lawsonia intracellularis and Brachyspira spp.), and systemic (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Streptococcus suis, and porcine circovirus). This approach is commonly used to attempt to understand the interaction between infectious agents resulting in pathology of certain systems, but we will propose and describe an alternative intervention-based approach below.

Porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC) is often multifactorial, with combinations of viruses, bacteria, and sometimes parasites causing severe losses. Respiratory disease is one of the most common causes of mortality attributed to infectious causes, with an estimated 47% of nursery mortality, 75% of grower/finisher mortality, and approximately 60% of wean-to-finish mortality associated with respiratory disease (USDA, 2015). Multiple pathogenic mechanisms may be additive or synergistic by enhancing colonization and organism virulence or compromising various host defense mechanisms. Examples include damage to the mucociliary apparatus, immunosuppression, altering cytokine responses, or reducing macrophage function (Yaeger and Van Alstine, 2019). Further description of the polymicrobial nature of PRDC has been described (Choi et al., 2003; Palzer et al., 2008; Opriessnig et al, 2011). Respiratory disease complex is augmented by interactions of infectious and noninfectious factors. Factors such as time between successive batches of pigs in a barn and air quality have been associated with increased incidence and severity of PRDC (Fablet et al., 2012a). This demonstrates the importance of the interaction of noninfectious contributors with infectious insults then resulting in pulmonary pathology and increased mortality. Morbidity estimates for PRDC in a number of different contexts have been reported to range from 1.9% to 40% and mortality from 2% to 20% (Baumann and Bilkei, 2002; Petersen et al., 2008; Hansen et al., 2010).

Enteric disease leads to mortality through impaired gastrointestinal structure or function. Infectious agents capable of damaging the gastrointestinal tract include but are not limited to L. intracellularis, Brachyspira spp., Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., coronaviruses, rotaviruses, and parasites. Similar to respiratory disease, multiple agents are often detected in clinical disease (Thomson et al., 1998; Stege et al., 2000; Thomson et al., 2001; Merialdi et al., 2003; Suh and Song, 2005; Reiner et al., 2011; Viott et al., 2013).

In addition to the respiratory and gastrointestinal system, infectious agents can also affect multiple body systems and result in mortality postweaning. [E. rhusiopathiae, porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2), pseudorabies virus (PRV), foreign animal diseases (FAD)] Many bacterial agents associated with PRDC (S. suis, G. parasuis, and Actinobacillus suis) can also result in systemic disease with arthritis, septicemia, and meningitis. Other postweaning mortality infectious causes include shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), which produces a toxin resulting in edema disease. Greasy pig disease, which may or may not be fatal, is a result of toxin production by Staphylococcus hyicus. Most of the agents responsible for systemic disease are commonly found in most swine herds. The diseases which may result, including polyserositis, erysipelas, edema disease, or other miscellaneous infections, accounted for 7.3% of pigs necropsied following euthanasia or death as reported by Baumann and Bilkei (2002). Another sporadic pathology associated with septicemia is bacterial endocarditis, which has been reported to be found in 0.019–0.038% of finishing pigs and has been associated with multiple etiologies, including Streptococcus spp, E. rhusiopathiae, Arcanobacterium pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus porcinus (Katsumi et al., 1997). Although a systems-based approach is commonly used to conceptualize infectious diseases, we hereafter propose an intervention-based framework.

Intervention-Based Overview

Varying levels of intervention can be used to control infectious causes of mortality, including: 1) aggressive depopulation of affected cohorts of animals, 2) elimination protocols using knowledge of immunity, not introducing naïve susceptible host animals for a sufficient period of time, with or without additional control measures, such as herd medication, or 3) less aggressive interventions. Using such an approach to conceptualizing infectious causes of postweaning mortality allows for a clearer understanding of the potential magnitude effect of prolonged presence of the etiologic agent in a swine production system.

Depopulation

The most aggressive approach to control infectious etiologies is through depopulation of affected herds. Historically, these protocols have been implemented with success for Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (APP) and swine dysentery, as well as others as described by Sasaki et al. (2016). Justification to implement such aggressive measures is dependent upon the realization that satisfactory production efficiency cannot be achieved with the agent present in the herd. In addition to the aforementioned agents, depopulation would likely be used for control and elimination of regulatory-designated FAD or pseudorabies virus if introduced into domestic swine populations in the United States because of higher-level concerns, including access to international trade partners.

Swine dysentery

Clinical disease known as swine dysentery is caused by Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Brachyspira hampsonii, and Brachyspira suanatina (Burrough, 2017; Hampson, 2018a; Rohde et al., 2018; Hampson and Burrough, 2019). The prevalence of Brachyspira spp. has been widely reported in the literature, but clinical disease associated with swine dysentery is much less frequent in the United States compared with historical rates (Hampson and Burrough, 2019). Morbidity for swine dysentery can be up to 90% of the population and mortality can be as high as 30% in extreme clinical settings and 50% in experimental settings (Hampson and Burrough, 2019). Depopulation and, in some cases, elimination strategies without depopulation have been implemented with success resulting in a relatively low prevalence in the United States.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae

Clinical disease caused by APP is characterized by rapid progression pneumonia with death sometimes within hours (Gottschalk and Broes, 2019). Clinical disease caused by APP has decreased over time, primarily through aggressive depopulation of affected herds, with only a small percentage of sites reporting clinical disease in recent years (USDA, 2016). Vaccination for APP in field trials has been shown to reduce absolute mortality by 3–5% or a relative reduction of 65–83% (Habrun et al., 2002; Del Pozo Sacristan et al., 2014; Table 2). Morbidity is estimated to range from 10% to 100% in clinically affected herds, with mortality ranging from less than 1% to 10% in acute outbreaks (Frank et al., 1992; Pozzi et al., 2011; Sassu et al., 2018). Nevertheless, globally, APP remains an aggressive and important etiologic agent with the potential to substantially contribute to postweaning mortality.

Table 2.

Efficacy of vaccination in field trials for various etiologies on postweaning mortalitya

| Mortality, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Vaccinated | Absolute difference, % | Relative difference, % | |

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae | ||||

| Habrun et al. (2002) | 5.8 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 82.8 |

| Del Pozo Sacristan et al. (2014) | 4.0 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 65.0 |

| Glasserella parasuis b | ||||

| McOrist et al. (2009) | 1.4–2.1 | 0.5–0.9 | — | — |

| Lawsonia intracellularis | ||||

| Almond et al. (2006) | 17.5 | 1.6 | 15.9 | 90.9 |

| Deitmer et al. (2011) | 3.3 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 3.0 |

| Peiponen et al. (2018) | 6.5 | 7.4 | −0.9 | −13.8 |

| Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae | ||||

| Bilic et al. (1996) | 3.1 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 100.0 |

| Maes et al. (1998) | 9.2 | 9.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Maes et al. (1999) | 4.0 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 5.0 |

| Pallares et al. (2000)c | 3.6 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 61.1 |

| Stipkovits et al. (2003) | 9.4 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 45.7 |

| Holyoake et al. (2006) | 4.2 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 9.5 |

| Tzivara et al. (2007) | 11.9 | 8.1 | 3.8 | 31.9 |

| Tassis et al. (2012) | 9.0 | 6.6d | 2.4 | 26.7 |

| Kristensen et al. (2014)e | 2.2 | 2.5f | −0.3 | −13.6 |

| Kristensen et al. (2014)g | 3.0 | 3.3f | −0.3 | −10.0 |

| PCV2 | ||||

| Cline et al. (2008) | 7.8 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 73.1 |

| Fachinger et al. (2008) | 8.7 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 24.1 |

| Horlen et al. (2008) | 18.4 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 51.1 |

| Kixmoller et al. (2008) | 7.5 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 53.3 |

| Desrosiers et al. (2009) | 9.5 | 2.4 | 7.1 | 74.7 |

| Neumann et al. (2009) | 10.4 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 51.9 |

| Segales et al. (2009) | 17.0 | 9.5 | 7.5 | 44.1 |

| Pejsak et al. (2010) | 28.8 | 16.1 | 12.7 | 44.1 |

| Takahagi et al. (2010)h | 20.8 | 12.1 | 8.7 | 41.8 |

| Takahagi et al. (2010)i | 26.5 | 13.7 | 12.8 | 48.3 |

| Takahagi et al. (2010)j | 14.7 | 14.1 | 0.6 | 4.1 |

| Jacela et al. (2011) | 5.9 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 47.5 |

| Venegas-Vargas et al. (2011) | 6.9 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 58.0 |

| Young et al. (2011) | 7.2 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 63.9 |

| Fraile et al. (2012) | 7.0 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 30.0 |

| Lee et al. (2012) | 32.2 | 8.0 | 24.2 | 75.2 |

| Potter et al. (2012) | 7.0 | 6.8 | 0.2 | 2.9 |

| Han et al. (2013) | 26.7 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 74.9 |

| Heibenberger et al. (2013) | 11.4 | 4.0 | 7.4 | 64.9 |

| Sidler et al. (2012) | 10.0 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 58.0 |

| Velasova et al. (2013) | 5.5 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 14.5 |

| Potter et al. (2014) | 11.0 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 29.1 |

| Jeong et al. (2015) | 16.7 | 11.1 | 5.6 | 33.5 |

| Martelli et al. (2016) | 13.4 | 9.9 | 3.5 | 26.1 |

| Villa-Mancera et al. (2016) | 26.5 | 8.3 | 18.2 | 68.7 |

| Czyzewska-Dors et al. (2018) | 5.3 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 5.7 |

| PRRSV | ||||

| Mavromatis et al. (1999) | 7.5 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 54.7 |

| Park et al. (2014) | 18.3 | 1.3 | 17.0 | 92.9 |

| Jeong et al. (2018) | 10.0 | 3.3 | 6.7 | 67.0 |

| Streptococcus suis | ||||

| Pejsak et al. (2001) | 4.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 51.1 |

| Hopkins et al. (2019)k | — | — | — | 21.0 |

aInformation could not be gathered for etiologies not listed in table. Values provided to illustrate the range in observed responses across studies and not intended to make scientific interpretation. Thus, results of statistical hypothesis testing is not provided.

bFormerly Haemophilus parasuis.

cAverage of all site types.

dIntramuscular vaccine treatment including both nursery and finishing periods.

eNursery portion of publication.

fAverage of two vaccination treatments using separate commercial vaccines.

gFinisher portion of publication.

hRepresents PCV2a-2 portion of investigation.

iRepresents PCV2b portion of investigation.

jRepresents PCV2a-1 portion of investigation.

k Hopkins et al. (2019) reported that administration of an autogenous Streptococcus suis vaccination reduced relative nursery mortality by 21%; however, did not provide specific estimates.

Pseudorabies virus

Pseudorabies virus, also known as suid herpesvirus 1 or Aujeszky’s disease, is an enveloped virus that can lead to reproductive losses, neurological signs, and mortality (Mettenleiter et al., 2019). Seroprevalence historically was 50% or greater in commercial herds (Elbers et al., 1992). The U.S. commercial swine herd was declared free of PRV in 2004 through intense eradication efforts (Pedersen et al., 2013). McNulty (2003) reported up to 20% mortality in pigs aged 14–20 wk. Pseudorabies remains prevalent in Asia (Hu et al., 2016), with highly virulent strains described with morbidity estimates of 30–80% and mortality estimates of 3–60% in commercial settings postweaning (Wu et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2014; Gu et al., 2015; Yamane et al., 2015) and high morbidity and mortality in experimental settings (Tong et al., 2015). Pseudorabies virus has been eradicated from commercial swine in the United States but remains a significant concern internationally, and the possibility of reintroduction is ever present and implications on morbidity and mortality could be significant.

Foreign animal disease

Multiple FAD present a risk for significant postweaning mortality, including African swine fever (ASF), classical swine fever (CSF), and foot and mouth disease (FMD) among others. While these diseases are not currently circulating in the United States, introduction may pose massive losses both via pathogenic mechanisms and voluntary depopulation to minimize disease spread. Possible routes of introduction could include live animals, meat, other swine swine-based products, or fomites, including feed or feed ingredients (Dee et al. 2018; Beltran-Alcrudo et al., 2019; Jurado et al., 2019; Niederwerder et al., 2019). It has been reported that mortality following exposure to CSF ranges from 40% to 48% (Laevens et al., 1999; Dewulf et al., 2000). During an outbreak of ASF in Nigeria in 2001, mortality estimates ranged from 76% to 91% in postweaning pigs (Babalobi et al., 2007). Mortality associated with FMD is much lower at an estimated 2.5% (Pozzi et al., 2019). While FAD are not currently in the United States, introduction of such diseases or novel diseases would lead to significant mortality through pathology or depopulation to control disease spread, loss of trade access, and economic and social implications.

Elimination

When the burden of infectious etiologies is too great to effectively manage, elimination of disease is often attempted. Elimination protocols often involve elimination of offending pathogen(s) from the sow farm producing weaners followed by weaning uninfected pigs to a depopulated, clean site. Sow farm elimination is by not introducing naïve animals for the time period sufficient for immune clearance to eliminate the pathogen and/or reduce shedding to levels that are not infective for susceptible animals when introduced. These protocols often involve periodic vaccination of the herd during the closure period and, with some bacteria, whole-herd antimicrobials prior to the introduction of naïve replacement animals at the end of the closure (Silva et al., 2019). Infectious organisms that have been successfully eliminated include Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (MHP), PRRSV, coronaviruses, including porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), and porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV), IAV, and nondysentery Brachyspira spp. Additionally, lice and mange can be managed with elimination but will not be discussed further as they currently do not lead to significant levels of postweaning mortality when using modern, confinement production practices.

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae

Mycoplasma spp. are very common organisms that lead to a number of disease processes, including an important role in PRDC through interactions with coetiologies. Clinical enzootic pneumonia is caused by MHP, historically the most important Mycoplasma sp. and a major contributor to PRDC (Pieters and Maes, 2019). The identification of MHP in swine is very common (Maes et al., 2000; Choi et al., 2003; Kukushkin and Okovytaya, 2012; Merialdi et al., 2012; Vangroenweghe et al., 2015; USDA, 2016). Clinical presentation of MHP can be asymptomatic but also can result in clinical disease without coetiologies. More commonly, disease results due to multifactorial infections (Thacker and Minion, 2012). Vaccination for MHP has variable impact on absolute mortality in field trials, ranging from slightly greater mortality to a reduction in mortality of 4% or a relative reduction up to 100% (Bilic et al., 1996; Maes et al., 1998; Maes et al., 1999; Pallares et al., 2000; Stipkovits et al., 2003; Holyoake et al., 2006; Tzivara et al., 2007; Tassis et al., 2012; Kristensen et al., 2014). Commercial production records from flows that were MHP negative had an absolute finishing mortality that was 1.26% lower compared with MHP-positive flows (Silva et al., 2019). Efforts have been directed toward MHP elimination from sow populations in recent years, and the probability of a sow herd being negative for MHP 1 year following herd closure has been reported to be 83% (Silva et al., 2019). Elimination protocols using whole-herd medication without herd closure have been implemented but with lower success rates (Silva et al., 2019).

Porcine reproductive and respiratory system virus

Clinical disease associated with PRRSV in postweaning pigs include respiratory disease, reduced growth rate, and increased mortality (Zimmerman et al., 2019). Coinfections with other respiratory viruses and bacteria are common with PRRSV infections. Disease associated with PRRSV is very common within the United States (Choi et al., 2003; Tousignant et al., 2015; USDA, 2016). Additionally, clinical disease associated with PRRSV has a very predictable seasonal pattern with greatest weekly incidence occurring during the fall and winter (Tousignant et al., 2015). Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus seropositive herds were associated with low grow-finish performance [including average daily gain (ADG), gain–feed ratio (G:F), mortality, and carcass weight] compared with PRRSV seronegative herds (Fablet et al., 2018). Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus status at the time of weaning had a significant impact on postweaning mortality, with positive batches of animals having a median relative increase in mortality of 34% over the expected mortality of the system, meaning that absolute mortality would be 1.8% greater in PRRSV-positive batches of animals compared with PRRSV-negative batches (Alvarez et al., 2015a). Additionally, grow-finish pigs that were PRRSV positive at weaning have been shown to have the greatest mortality, followed by pigs that became PRRSV positive at some point during the grow-finish period and pigs that were PRRSV negative throughout (9.3%, 7.4%, and 6.0% mortality, respectively; Holtkamp et al., 2013). Vaccination for PRRSV in field trials has been shown to reduce absolute mortality by 4–17% or a relative reduction of 55–93% (Mavromatis et al., 1999; Park et al., 2014; Jeong et al., 2018). In one report where a vaccination program was initiated following a PRRSV outbreak in a sow farm, nursery mortality was reported to be 9.3% during the first 18 wk of the outbreak and was reduced to 2.2% 19 wk later following resolution of clinical disease (Kvisgaard et al., 2017). Morbidity rates have been reported to range from 45% to 100%, with 20–100% mortality (Tong et al., 2007; Lyoo et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017; Dong et al., 2018). Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus is a very common and frustrating virus that results in respiratory disease among other disorders. The major impact of PRRSV on postweaning pigs is the contribution to PRDC, which can lead to significant mortality.

Swine influenza virus A

Clinical disease associated with IAV is common (Loeffen et al., 1999; Choi et al., 2003; USDA, 2016), and morbidity within a population can be high. Synergistic effects have been observed with both bacteria and viruses in conjunction with IAV (Van Reeth and Vincent, 2019). Morbidity and mortality range significantly depending on situation-specific factors, including immunity, other infectious agents present, and management/control factors being implemented. When acting alone, IAV does not often lead to substantial mortality. Interactions with other infectious agents often are an outcome of IAV infections that can lead to mortality. Influenza status at the time of weaning had a significant impact on postweaning mortality, with positive batches of pigs having a median increase in relative mortality of 13% over the expected mortality of the system (Alvarez et al., 2015a). Infection with IAV is extremely common, and a large percentage of pigs are exposed at some point in their lifetime. Morbidity estimates vary greatly but are of little value without consideration of other infectious agents. Morbidity estimates have been reported to increase by 2–100% when exposed to various IAV biotypes, and mortality has been reported to range from 1% to 10% (Ma et al., 2010; Welsh et al., 2010; Markowska-Daniel et al., 2013). IAV is a common infectious agent providing a significant contribution to PRDC and subsequent mortality.

Nondysentery Brachyspira spp.

Disease caused by nondysentery Brachyspira spp. include porcine intestinal spirochetosis caused by Brachyspira pilosicoli (Trott et al., 1996; Hampson, 2018b), as well as colitis caused by Brachyspira murdochii and Brachyspira intermedia (Hampson and Burrough, 2019). Infection with B. pilosicoli has been reported to result in reduced growth performance with watery diarrhea (Hampson, 2018b), with morbidity between 5% and 15% in growing pigs with mortality approximately 1% (Thomson et al., 1998). Additionally, colitis caused by B. murdochii and B. intermedia is thought to be self-limiting and leads to minimal morbidity and mortality (Hampson and Burrough, 2019). The impact on morbidity and mortality attributed to nondysentery Brachypira spp. is relatively minimal compared to swine dysentery.

Coronaviruses

Swine enteric coronaviruses (SEC) are enveloped viruses including PEDV, TGEV, and PDCoV. Porcine respiratory coronaviruses are believed to be derived from TGEV through the deletion of a spike gene and were first described in the 1980s (Saif et al., 2019). The clinical significance of porcine respiratory coronavirus has been much lower compared with enteric coronaviruses, and additional information can be found elsewhere. Enteric coronaviruses replicate within the enterocytes of the small intestine, leading to profound epithelial necrosis, villus atrophy, severe maldigestive, and malabsorptive diarrhea (Saif et al., 2019). The age when pigs are infected impacts on morbidity and mortality, with morbidity and mortality nearly 100% in pigs less than 7 d of age, 60–85% morbidity with low mortality if infected from 14 to 28 d of age, and lesser morbidity and mortality thereafter (Shibata et al., 2000; Madson et al., 2014). When comparing postweaning batches of pigs either PEDV positive or PEDV negative, it has been shown that PEDV-positive batches have a mean increase in mortality of 2–11% compared with PEDV-negative batches (Alvarez et al., 2015b; Yamane et al., 2016). Swine enteric coronaviruses lead to very high morbidity and mortality rates in young pigs, with less severe impacts postweaning. Nonetheless, SEC can result in substantial postweaning morbidity and mortality.

Infectious Agents Often Managed Without Depopulation/Elimination

Multiple postweaning mortality infectious causes have not been aggressively controlled through depopulation or elimination methods. Reasoning for lack of depopulation or elimination efforts are due to the high efficacy of immunization (e.g., PCV2) or are extremely common inhabitants of swine and/or the environment. Multiple infectious agents within this category can result in mortality without coinfections, while others are commonly associated with coinfections leading to multifactorial disease. However, most of these organisms do have noninfectious risk factors for disease expression. Protozoa such as Cystoisospora suis and Eimeria spp. can occasionally result in diarrhea postweaning, but clinical disease has much greater significance preweaning (Lindsay et al., 2019). Additionally, nematodes such as Ascaris suum and others are common if swine have access to dirt and can be managed with anthelmintic drugs (Brewer and Greve, 2019). Protozoa and nematodes can be minor factors contributing to postweaning mortality in modern, intensive swine production systems but will not be discussed further.

Streptococcus spp.

While Streptococcus spp. are often present in healthy animals, significant disease can result, most commonly associated with S. suis (MacInnes et al., 2008; USDA, 2016). Infection with PRRSV has been shown to increase susceptibility to S. suis infection (Thanawongnuwech et al., 2000; Li et al., 2019). Systemic infections (sepsis or septicemia) result in multiple disease processes, including meningitis, polyserositis (epicarditis, pleuritis, and peritonitis), synovitis, arthritis, endocarditis, encephalitis, abortions, and abscesses (Staats et al., 1997). It has been observed that pigs are more likely to die due to S. suis if one or more littermates died during the nursery phase (Hopkins et al., 2018). Additionally, mortality associated with S. suis during the study period was shown to be less in offspring from sow’s second litter compared with the first (Hopkins et al., 2018). Together, these results suggested that mortality in a farm experiencing S. suis-related disease is associated with maternal influence. Vaccines have been shown to reduce relative postweaning mortality from 21% to 51% compared with nonvaccinated cohorts (Pejsak et al., 2001; Hopkins et al., 2019). It has been reported that morbidity ranges are highly variable from less than 0.3–80% but most commonly below 5% (St. John et al., 1982; Staats et al., 1997) with an associated case fatality risk of 2–100% (St. John et al., 1982) based on a number of cofactors. This wide range of morbidity and mortality estimates can be at least partially attributed to the confounded nature of multiple bacterial agents typically involved and difficulty identifying certain pathological manifestations. Treatment has been reported to be successful when performed early with mortality ranging from 0% to 5%, but herd mortality has been reported to be as high as 20% in some situations (Staats et al., 1997; Torremorell et al., 1997; Villani et al., 2003; Hopkins et al., 2018). Streptococcus suis is a common infectious agent identified in swine production settings and can lead to substantial postweaning morbidity and mortality.

Glasserella (formerly Haemophilus) parasuis

Glasser’s disease is caused by this gram-negative bacterial species, characterized by fibrinous polyserositis and septicemia with tissue localizations in brain, joints, or lungs (Aragon et al., 2019). Glasserella parasuis is commonly present and can lead to significant mortality in populations of animals with no previous exposure. This diverse organism is a common inhabitant of the nasopharyx (Smart et al., 1989; Choi et al., 2003; MacInnes et al., 2008; USDA, 2016) but, when sepsis occurs, presents with clinical signs similar to signs observed with S. suis. Like S. suis, G. parasuis may interact with PRRSV to contribute to PRDC (Kavanova et al., 2017), although clear evidence of such an interaction was not observed by Solano et al. (1997). Vaccination of sows with an autogenous G. parasuis vaccine has been shown to reduce offspring nursery mortality (1.4–2.1% monthly mortality for control vs. 0.5–0.9% monthly mortality for vaccinated; McOrist et al., 2009). An important consideration when interpreting results of any vaccination trial for this or other pathogens is the potential for underlying publication bias, as well as confounding factors. Mortality rates can range from 5% to 10% in herds with previous exposure (Nielsen and Danielsen, 1975; Smart et al., 1993; Aragon et al., 2019) and up to 75% in naïve herds (Aragon et al., 2012).

Pasteurella multocida

Clinical disease associated with P. multocida occurs as either upper respiratory tract disease known as progressive atrophic rhinitis (PAR, commonly serotype D) or lower respiratory tract pneumonia (commonly serotype A). Pasteurella multocida can be commonly isolated from the respiratory tract of pigs and is historically very important due to PAR. Progressive atrophic rhinitis is caused by specific toxin-producing strains of P. multocida that either alone or in combination with Bordetella bronchiseptica can lead to destruction of the nasal turbinates and deformation of the snout (Register and Brockmeier, 2019). The occurrence of PAR is now relatively rare, and elimination strategies have been successful over time.

Generally, P. multocida alone is poorly effective at attaching and colonizing lower respiratory epithelium. When damage to the respiratory mucosa and debris-clearing mechanism occurs, colonization can occur leading to pneumonia (Register and Brockmeier, 2019). Thus, pneumonia due to P. multocida is largely dependent on other infectious agents to compromise pulmonary clearance or establish the early stages of clinical disease and, then, secondarily colonizes and contributes to disease. Vaccination with both inactivated P. multocida and B. bronchiseptica antigen has been shown to reduce postweaning mortality (5.3% for vaccinated group vs. 10.1% for unvaccinated group; Stojanac et al., 2013). Pasteurella multocida-associated disease has resulted in mortality from 5% to 40% in pigs of all ages (Pijoan and Fuentes, 1987; Cameron et al., 1996; Register et al., 2012). Like many respiratory infectious agents, providing specific estimates of mortality is difficult and dependent on a number of population-specific factors, including the presence of coinfections. The overall incidence of progressive atrophic rhinitis is very low with multisite, all-in/all-out production.

Bordetella bronchiseptica

The primary agent associated with reversible, nonprogressive atrophic rhinitis is the gram-negative rod bacteria B. bronchiseptica (Brockmeier et al., 2019). The presence of P. multocida, with or without B. bronchiseptica, results in much more severe progressive atrophic rhinitis (Brockmeier et al., 2019). Bordetella bronchiseptica is associated with respiratory disease as a primary cause of pneumonia through colonization enhanced by other infectious agents, such as IAV and through enhancing colonization of other infectious agents (Loving et al., 2010; Brockmeier et al., 2019). Bordetella bronchiseptica is commonly isolated from the respiratory tract of pigs (Choi et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2014) and can contribute to multifactorial disease processes historically, including atrophic rhinitis and most commonly PRDC. Estimates of morbidity and mortality are not available largely due to the complex multifactorial nature of resulting disease.

Other Mycoplasma spp.

Additional Mycoplasma spp. are commonly isolated and associated with disease processes in swine, including Mycoplasma hyosynoviae resulting in arthritis in grow-finish pigs, Mycoplasma hyorhinis resulting in polyserositis and arthritis, and Mycoplasma suis resulting in loss of red blood cells (Pieters and Maes, 2019). While estimates of the impact on morbidity and mortality are not available, the magnitude of effect is believed to be relatively low.

Actinobacillus suis

Sepsis due to A. suis can be very severe, but A. suis has a lower attack rate compared to APP. Isolation of A. suis is common in the upper respiratory organism of pigs (Gottschalk and Broes, 2019). Infection with A. suis has been described to lead to significant preweaning pig mortality (Sanford et al., 1990). This organism is associated with acute sepsis, serositis, and pneumonia in all stages postweaning, with or without other identified cofactors. The clinical significance is historically less in postweaning populations compared to APP, with little information available regarding estimates of magnitude of effect.

Lawsonia intracellularis

Clinical disease due to L. intracellularis is known as ileitis, garden hose gut, or porcine proliferative enteropathy (Vannucci et al., 2019). Lawsonia intracellularis is a common organism (Chang et al., 1997; Chiriboga et al., 1999; Stege et al., 2000; Jacobson et al., 2005; Biksi et al., 2007; Dors et al., 2015; Weber et al., 2015; USDA, 2016) affecting postweaning pigs. Vaccination for L. intracellularis in field trials has shown variable effects ranging from slightly increased mortality with vaccination to reduction of absolute mortality by up to 16% or a relative reduction of 91% (Almond et al., 2006; Deitmer et al., 2011; Peiponen et al., 2018). Morbidity rates in cases of hemorrhagic enteropathy can range from 12% to 50%, and up to 50% of animals affected may result in mortality (Lawson and Gebhart, 2000; Kroll et al., 2005), whereas chronic disease can result in mortality around 1% (Lawson and Gebhart, 2000; Pejsak et al., 2009). Lawsonia intracellularis is common in swine herds and, in nonvaccinated populations, can cause moderate levels of morbidity and mortality as a result of acute and chronic manifestations of disease.

Salmonella spp.

Clinical disease due to Salmonella spp. are primarily due to Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium and S. enterica serotype choleraesuis (Griffith et al., 2019). Host-adapted Salmonella choleraesuis affects postweaning pigs and results in septicemia (Griffith et al., 2019), whereas Salmonella typhimurium is more like to be manifested with diarrhea and dehydration. In the United States, S. typhimurium is isolated with greater frequency compared to S. choleraesuis (Foley et al., 2008; Griffith et al., 2019). The mortality associated with S. typhimurium is reportedly low (Griffith et al., 2019), although specific estimates are not available. Cases of S. choleraesuis often result in a morbidity of <10% with a high case fatality risk (Griffith et al., 2019). Pedersen et al. (2015) reported mortality ranging from 20% to 30% in Danish herds following an outbreak of S. choleraesuis. Due to the zoonotic nature of Salmonella, numerous studies have investigated Salmonella prevalence in swine populations, which are widely available in published literature. One recent report describes such changes from 1997 to 2015, reporting an increase in the prevalence of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:i- (Yuan et al., 2018), and has been associated with clinical disease (Shippy et al., 2018; Arruda et al., 2019; Naberhaus et al., 2019). Other Salmonella spp. remain important potential contributors to postweaning mortality with the additional ever-present risk of zoonosis.

Escherichia coli

Multiple disease processes in postweaning pigs are a result of the gram-negative bacterium, including postweaning diarrhea, edema disease, and septicemia/endotoxemia, (Fairbrother and Nadeau, 2019). A case-control study comparing 50 Canadian nurseries with and without postweaning E. coli was performed and found that the mortality in case farms was 7.7% compared to 1.8% in control farms (Amezcua et al., 2002). Postweaning diarrhea can result in mortality up to 25% but is more commonly much lower ranging from 1.5% to 2% (Fairbrother and Nadeau, 2019). Escherichia coli is a common enteric infectious agent that results in morbidity in postweaning pigs. The magnitude on mortality is often mild to moderate but can be more severe in select cases.

The edema caused by STEC is due to toxin production that enters the circulatory system and damages blood vessel walls, leading to fluid leakage into extravascular tissues (Fairbrother and Nadeau, 2019). Edema disease is relatively infrequent (USDA, 2016). Sporadic mortality can occur with a case mortality rate from 50% to 90% (Fairbrother and Nadeau, 2019). Edema disease secondary to toxin production by STEC is relatively uncommon and is not a major contributor to postweaning mortality.

Rotaviruses

Multiple rotavirus groups have been identified, with rotavirus A being the most common and pathogenic to pigs, B being less common, and C primarily affecting preweaning pigs (Shepherd et al., 2019). Rotavirus infections also occur with other etiologies, increasing the severity of disease (Shepherd et al., 2019). Viral replication occurs within the epithelium of the intestine, leading to villus blunting and reduced absorptive capacity. Rotavirus C has been reported to cause 60–80% morbidity in feeder pigs with no mortality (Kim et al., 1999). Morbidity associated with mixed rotavirus infections has been reported to be as high as 70%, with mortality rates as high as 11% (Molinari et al., 2016). Research has also used molecular diagnostic techniques to characterize the presence of rotavirus from postweaning pigs with diarrhea (Martella et al., 2007; Lorenzetti et al., 2011). A common presentation of rotavirus infections occurs within the preweaning period as piglet diarrhea but can be a contributing etiology to postweaning diarrhea also. Rotavirus can result in significant malabsorptive diarrhea in postweaning pigs due to villous blunting and, especially in the presence of coinfections, can be a contributor to postweaning mortality from other causes, such as colibacillosis, salmonellosis, or inanition.

Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome

Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS), also known as intestinal hemorrhage syndrome, porcine intestinal distention syndrome, or bloody gut, presents as sudden death in combination with abdominal distention and red discoloration of the intestine similar to mesenteric torsion (Grahofer et al., 2017; Thomson and Friendship, 2019). The reported distinguishing factor from a mesenteric torsion is that no clear torsion is evident upon initial examination with HBS. Distention of the intestines without mesenteric torsion is believed to be associated with highly fermentable diet, such as liquid whey, leading to increased intra-abdominal pressure and reduced venous blood flow (Thomson and Friendship, 2019), although various other contributing factors have been described, including infectious etiologies (Novotny et al., 2016; Grahofer et al., 2017). Historically, HBS has been reported to account for approximately 2–5% of yearly finishing pig mortality and as severe as 10–20% mortality in the 1960s and 1970s (Straw et al., 2002). HBS as an independent disease process from torsion remains speculative because, in many cases, thorough evaluation will identify organ volvulus and/or torsion. There is currently no consensus regarding the cause of HBS in finishing pigs. It is clear that mortality does occur due to abnormalities that have been historically classified due to gross appearance as HBS. Further understanding of the complex pathophysiology is necessary, as well as astute postmortem examination, to accurately identify the cause of mortality.

Staphylococcus spp.

Although Staphylococcus spp. are nearly ubiquitous in commercial swine production, clinical disease is relatively infrequent. Two primary etiologies cause disease in swine, including exudative epidermitis (greasy pig disease) caused by S. hyicus and multiple disease processes caused by S. aureus (Frana and Hau, 2019). Greasy pig disease due to S. hyicus has been reported to cause 14% morbidity in nursery pigs, with 5% mortality (Arsenakis et al., 2018). Additionally, S. aureus occasionally is associated with skin infections, septicemia, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis (Frana and Hau, 2019) but is not an infectious agent of major clinical relevance in swine. The primary concern regarding S. aureus is swine acting as a reservoir for the zoonotic methicillin-resistant S. aureus (Frana and Hau, 2019), and prevalence estimates have been described by Sun et al. (2015). Staphylococcus spp. are extremely common organisms; however, the clinical significance today is much reduced compared to historical magnitudes of effect.

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae

Clinical disease associated with E. rhusiopathiae commonly known as erysipelas include septicemia, infectious arthritis, endocarditis, and skin lesions (Opriessnig and Coutinho, 2019). Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is present globally and is estimated that it can be isolated from the tonsils of 30–50% of apparently healthy pigs (Opriessnig and Coutinho, 2019). The yearly incidence from 1972 to 1979 in Minnesota ranged from 0 to 99 cases per 1,000 farrow-to-finish pigs (Wood et al., 1984). More recently, outbreaks in naïve populations can have mortality ranging from 20% to 40% in extreme cases (Opriessnig and Coutinho, 2019). The estimates of morbidity and mortality in nonnaïve outbreaks are variable and have not been clearly determined. Thus, E. rhusiopathiae remains a threat for significant morbidity and mortality in naïve or improperly vaccinated populations but is not commonly a cause of significant postweaning mortality.

Porcine circovirus

Porcine circovirus has multiple types, including the nonpathogenic type 1 and PCV2 and, recently, type 3 has been identified as associated with clinical disease (Palinski et al., 2016; Arruda et al., 2019; Segales et al., 2019). Manifestations of porcine circovirus-associated disease (PCVAD) include PCV2 systemic disease (PCV2-SD, formerly postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome), PCV2 reproductive disease (PCV2-RD), porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome, and subclinical infections (Segales et al., 2019). Porcine circovirus type 2 has been commonly demonstrated to be present in PRDC-affected swine along with multiple other coetiologies (Kim et al., 2003; Hansen et al., 2010; Wellenberg et al., 2010; Ouyang et al., 2019). It is currently believed that respiratory disease associated with PCV2 are due to PCV2-SD and not primary lung pathology (Fablet et al., 2012b; Tico et al., 2013; Segales et al., 2019).

Widespread use of PCV2 vaccines is due to their efficacy in reducing clinical disease and mortality. A meta-analysis was published in 2011 comparing the efficacy of PCV2 vaccines at reducing postweaning mortality, which found that vaccination results in an absolute reduction of nursery-finish mortality of 5.4% and reduction of finish mortality of 4.4% (Kristensen et al., 2011). Across field studies identified in this review, the magnitude of impact on absolute mortality associated with PCV2 vaccination ranged from 0% to 24% or up to 75% relative reduction (Cline et al., 2008; Fachinger et al., 2008; Horlen et al., 2008; Kixmoller et al., 2008; Desrosiers et al., 2009; Neumann et al., 2009; Segales et al., 2009; Pejsak et al., 2010; Takahagi et al., 2010; Jacela et al., 2011; Venegas-Vargas et al., 2011; Young et al., 2011; Fraile et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012; Potter et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013; Heibenberger et al., 2013; Sidler et al., 2012; Potter et al., 2014; Jeong et al., 2015; Martelli et al., 2016; Villa-Mancera et al., 2016; Czyzewska-Dors et al., 2018). Herds with high PCV2 antibody titers have been associated with reduced grow-finish performance (combined ADG, G:F, mortality, and carcass weight) compared to herds with lower PCV2 titers (Fablet et al., 2018). PCV2-SD had been shown to result in morbidity ranging from 1.6% to 60% and mortality ranging from 3% to 56% (Jemersic et al., 2004; D’Allaire et al., 2007; Horlen et al., 2007; Carman et al., 2008; Nielsen et al., 2008; Neumann et al., 2009; Pejsak et al., 2010; Woodbine et al., 2010; Shelton et al., 2012; Segales et al., 2019). PCV2 is a very common infectious agent that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in unvaccinated populations.

Neurological syndromes associated with viral agents

In recent years, an increase in the incidence of neurological syndromes has been observed and, in many cases, associated with diagnosis of viral infectious agents. This is still an area of ongoing research efforts, but multiple viruses recently have been associated with neurological syndromes, including porcine sapelovirus (Schock et al., 2014; Arruda et al., 2017b), porcine astrovirus type 3 (Boros et al., 2017; Rawal et al., 2019; Matias Ferreyra et al., 2020), and porcine teschovirus (Bangari et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2012; Carnero et al., 2018). The recently described atypical porcine pestivirus has been associated with congenital tremors (de Groof et al., 2016; Postel et al., 2016; Schwarz et al., 2017) but is not believed to be a major contributor to postweaning mortality (Gatto et al., 2019). Other viruses that can cause neurological conditions include PRV, classical swine fever, Japanese encephalitis virus, and PRRSV among others (Madson et al., 2019), but the current focus will be pertaining to porcine sapelovirus, porcine astrovirus type 3, and porcine teschovirus.

A recent investigation into neurological signs, including ataxia, paresis, and paralysis in 11-wk-old pigs, associated with porcine sapelovirus reported a morbidity of 20% and a case fatality rate of 30% (Arruda et al., 2017b). Porcine astrovirus type 3 has been reported to result in 1.5–4% mortality in weaned pigs (Boros et al., 2017), and a separate investigation reported a 75% case fatality rate (Arruda et al., 2017a). Porcine teschovirus has been reported to result in morbidity ranging from 3% to 60% with a case fatality rate of approximately 60% (Bangari et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2012; Carnero et al., 2018). There are a number of neurologic cases that never have a confirmed cause, and a significant amount of information remains unknown regarding the prevalence and clinical impact of these viruses.. Finally, it is human nature to lump and categorize observations based on previous experiences and personal bias based on similar clinical presentation. Such diagnoses many times do not have sufficient evidence to derive such interpretations. This is by no means specific to neurologic diagnoses. It is important to recognize limitations in our knowledge base and accept that establishing a clear diagnosis is often challenging. This becomes very important when evaluating mortality data and attempting to make clinical decisions among the complexity of interactions between infectious and noninfectious factors contributing to mortality.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, various strategies have been used to control infectious disease in swine, including depopulation, elimination, and less aggressive measures. Depopulation and elimination practices have been shown to be successful and clearly have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality reduction in affected populations. Important diseases and their infectious agents that have been a focus to eliminate through herd depopulation or elimination should continue to be a focus to have the greatest impact on minimization of postweaning mortality.

LITERATURE CITED

- Almond P. K., and Bilkei G... 2006. Effects of oral vaccination against Lawsonia intracellularis on growing-finishing pig’s performance in a pig production unit with endemic porcine proliferative enteropathy (PPE). Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 113:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Spilsbury M., Ramirez-Necoechea R., Gonzalez-Lozano M., Mota-Rojas D., and Trujilo-Ortega M. E... 2007. Piglet survival in early lactation: a review. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 6:76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J., Sarradell J., Kerkaert B., Bandyopadhyay D., Torremorell M., Morrison R., and Perez A... 2015a. Association of the presence of influenza A virus and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in sow farms with post-weaning mortality. Prev. Vet. Med. 121:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J., Sarradell J., Morrison R., and Perez A... 2015b. Impact of porcine epidemic diarrhea on performance of growing pigs. PLoS One. 10:e0120532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amezcua R., Friendship R. M., Dewey C. E., Gyles C., and Fairbrother J. M... 2002. Presentation of postweaning Escherichia coli diarrhea in southern Ontario, prevalence of hemolytic E. coli serogroups involved, and their antimicrobial resistance patterns. Can. J. Vet. Res. 66:73–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragon V., Segales J., and Oliveira S... 2012. Glasser’s disease. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., and Stevenson G. W., editors, Diseases of swine. 10th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 760–769. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon V., Segales J., and Tucker A. W... 2019. Glasser’s disease. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine. 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 844–853. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda B., Arruda P., Hensch M., Chen Q., Zheng Y., Yang C., Gatto I. R. H., Ferreyra F. M., Gauger P., Schwartz K.,. et al. 2017a. Porcine astrovirus type 3 in central nervous system of swine with polioencephalomyelitis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23:2097–2100. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.170703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda P. H., Arruda B. L., Schwartz K. J., Vannucci F., Resende T., Rovira A., Sundberg P., Nietfeld J., and Hause B. M... 2017b. Detection of a novel sapelovirus in central nervous tissue of pigs with polioencephalomyelitis in the USA. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 64:311–315. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda B. L., Burrough E. R., and Schwartz K. J... 2019. Salmonella enterica I 4,[5],12:i:- associated with lesions typical of swine enteric salmonellosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25:1377–1379. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.181453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda B., Piñeyro P., Derscheid R., Hause B., Byers E., Dion K., Long D., Sievers C., Tangen J., Williams T.,. et al. 2019. PCV3-associated disease in the United States swine herd. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 8:684–698. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1613176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenakis I., Boyen F., Haesebrouck F., and Maes D. G. D... 2018. Autogenous vaccination reduces antimicrobial usage and mortality rates in a herd facing severe exudative epidermitis outbreaks in weaned pigs. Vet. Rec. 182:744. doi: 10.1136/vr.104720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalobi O. O., Olugasa B. O., Oluwayelu D. O., Ijagbone I. F., Ayoade G. O., and Agbede S. A... 2007. Analysis and evaluation of mortality losses of the 2001 African swine fever outbreak, Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 39:533–542. doi: 10.1007/s11250-007-9038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangari D. S., Pogranichniy R. M., Gillespie T., and Stevenson G. W... 2010. Genotyping of Porcine teschovirus from nervous tissue of pigs with and without polioencephalomyelitis in Indiana. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 22:594–597. doi: 10.1177/104063871002200415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann B., and Bilkei G... 2002. Emergency-culling and mortality in growing/fattening pigs in a large Hungarian “farrow-to-finish” production unit. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 109:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran-Alcrudo D., Falco J. R., Raizman E., and Dietze K... 2019. Transboundary spread of pig diseases: the role of international trade and travel. BMC Vet. Res. 15:64. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1800-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereskin B., Shelby C. E., and Cox D. F... 1973. Some factors affecting pig survival. J. Anim. Sci. 36:821–827. doi: 10.2527/jas1973.365821x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biksi I., Lorincz M., Molnár B., Kecskés T., Takács N., Mirt D., Cizek A., Pejsak Z., Martineau G. P., Sevin J. L.,. et al. 2007. Prevalence of selected enteropathogenic bacteria in Hungarian finishing pigs. Acta Vet. Hung. 55:219–227. doi: 10.1556/AVet.55.2007.2.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilić V., Lipej Z., Valpotić I., Habrun B., Humski A., and Njari B... 1996. Mycoplasmal pneumonia in pigs in Croatia: first evaluation of a vaccine in fattening pigs. Acta Vet. Hung. 44:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros Á., Albert M., Pankovics P., Bíró H., Pesavento P. A., Phan T. G., Delwart E., and Reuter G... 2017. Outbreaks of neuroinvasive astrovirus associated with encephalomyelitis, weakness, and paralysis among weaned pigs, hungary. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23:1982–1993. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.170804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M. T., and Greve J. H... 2019. Internal parasites. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine. 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 1005–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeier S. L., Register K. B., Nicholson T. L., and Loving C. L... 2019. Bordetellosis. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., and Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine. 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 767–777. [Google Scholar]

- Burrough E. R. 2017. Swine dysentery: etiopathogenesis and diagnosis of a reemerging disease. Vet. Path. 54:22–31. doi: 10.1177/0300985816653795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron R. D., O’Boyle D., Frost A. J., Gordon A. N., and Fegan N... 1996. An outbreak of haemorrhagic septicaemia associated with Pasteurella multocida subsp gallicida in large pig herd. Aust. Vet. J. 73:27–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1996.tb09949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman S., Cai H. Y., DeLay J., Youssef S. A., McEwen B. J., Gagnon C. A., Tremblay D., Hazlett M., Lusis P., Fairles J.,. et al. 2008. The emergence of a new strain of porcine circovirus-2 in Ontario and Quebec swine and its association with severe porcine circovirus associated disease–2004-2006. Can. J. Vet. Res. 72:259–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnero J., Prieto C., Polledo L., and Martínez-Lobo F. J... 2018. Detection of Teschovirus type 13 from two swine herds exhibiting nervous clinical signs in growing pigs. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 65:e489–e493. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. L., Wu C. F., Wu Y., Kao Y. M., and Pan M. J... 1997. Prevalence of Lawsonia intracellularis in swine herds in Taiwan. Vet. Rec. 141:103–104. doi: 10.1136/vr.141.4.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiriboga A. E., Guimarães W. V., Vanetti M. C., and Araújo E. F... 1999. Detection of Lawsonia intracellularis in faeces of swine from the main producing regions in Brazil. Can. J. Microbiol. 45:230–234. doi: 10.1139/w98-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. K., Goyal S. M., and Joo H. S... 2003. Retrospective analysis of etiologic agents associated with respiratory diseases in pigs. Can. Vet. J. 44:735–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline G., Wilt V., Diaz E., and Edler R... 2008. Efficacy of immunising pigs against porcine circovirus type 2 at three or six weeks of age. Vet. Rec. 163:737–740. doi: 10.1136/vr.163.25.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelison A. S., Karriker L. A., Williams N. H., Haberl B. J., Stalder K. J., Schulz L. L., and Patience J. F... 2018. Impact of health challenges on pig growth performance, carcass characteristics, and net returns under commercial conditions. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2:50–61. doi: 10.1093/tas/txx005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewska-Dors E. B., Dors A., Pomorska-Mól M., Podgórska K., and Pejsak Z... 2018. Efficacy of the Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) vaccination under field conditions. Vet. Ital. 54:219–224. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.1009.5377.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Allaire S., Moore C., and Côté G... 2007. A survey on finishing pig mortality associated with porcine circovirus diseases in Quebec. Can. Vet. J. 48:145–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee S. A. Bauermann F. V., Niederwerder M. C., Singrey A., Clement T., de Lima M., Long C., Patterson G., Sheahan M. A., Stoian A. M. M., et al. 2018. Survival of viral pathogens in animal feed ingredients under transboundary shipping models. PLoS One. 13:e0194509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groof A., Deijs M., Guelen L., van Grinsven L., van Os-Galdos L., Vogels W., Derks C., Cruijsen T., Geurts V., Vrijenhoek M.,. et al. 2016. Atypical porcine pestivirus: a possible cause of congenital tremor type A-II in newborn piglets. Viruses. 8:271. doi: 10.3390/v8100271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitmer R., Klien K., and Adam M... 2011. The effects of cessation of ileitis vaccination on performance parameters and antibiotic use. Prakt. Tierarzt. 92:510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo Sacristán R., Michiels A., Martens M., Haesebrouck F., and Maes D... 2014. Efficacy of vaccination against Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae in two Belgian farrow-to-finish pig herds with a history of chronic pleurisy. Vet. Rec. 174:302. doi: 10.1136/vr.101961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M. Y., Millien M., Jacques-Simon R., Flanagan J. K., Bracht A. J., Carrillo C., Barrette R. W., Fabian A., Mohamed F., Moran K.,. et al. 2012. Diagnosis of Porcine teschovirus encephalomyelitis in the Republic of Haiti. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24:671–678. doi: 10.1177/1040638712445769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers R., Clark E., Tremblay D., Tremblay R., and Polson D... 2009. Use of a one-dose subunit vaccine to prevent losses associated with porcine circovirus type 2. J. Swine Health Prod. 17:148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dewulf J., Laevens H., Koenen F., Vanderhallen H., Mintiens K., Deluyker H., and de Kruif A... 2000. An experimental infection with classical swine fever in E2 sub-unit marker-vaccine vaccinated and in non-vaccinated pigs. Vaccine 19:475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohoo I., Martin W., and Stryhn H... 2003. Veterinary epidemiologic research. AVC Inc., Charlottetown, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Dong J. G., Yu L. Y., Wang P. P., Zhang L. Y., Liu Y. L., Liang P. S., and Song C. X... 2018. A new recombined porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus virulent strain in China. J. Vet. Sci. 19:89–98. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2018.19.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dors A., Pomorska-Mól M., Czyżewska E., Wasyl D., and Pejsak Z... 2015. Prevalence and risk factors for Lawsonia intracellularis, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and Salmonella spp. in finishing pigs in Polish farrow-to-finish swine herds. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 18:825–831. doi: 10.1515/pjvs-2015-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbers A. R. W., Tielen M. J. M., Cromwijk W. A. J., and Hunneman W. A... 1992. Variation in seropositivity for some respiratory disease agents in finishing pigs: epidemiological studies on some health paramerters and farm and management conditions in the herds. Vet. Q. 14:8–13. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1992.9694318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fablet C., Dorenlor V., Eono F., Eveno E., Jolly J. P., Portier F., Bidan F., Madec F., and Rose N... 2012a. Noninfectious factors associated with pneumonia and pleuritis in slaughtered pigs from 143 farrow-to-finish pig farms. Prev. Vet. Med. 104:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fablet C., Marois-Créhan C., Simon G., Grasland B., Jestin A., Kobisch M., Madec F., and Rose N... 2012b. Infectious agents associated with respiratory diseases in 125 farrow-to-finish pig herds: a cross-sectional study. Vet. Microbiol. 157:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fablet C., Rose N., Grasland B., Robert N., Lewandowski E., and Gosselin M... 2018. Factors associated with the growing-finishing performances of swine herds: an exploratory study on serological and herd level indicators. Porcine Health Manag. 4:6. doi: 10.1186/s40813-018-0082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fachinger V., Bischoff R., Jedidia S. B., Saalmüller A., and Elbers K... 2008. The effect of vaccination against porcine circovirus type 2 in pigs suffering from porcine respiratory disease complex. Vaccine 26:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother J. M., and Nadeau E... 2019. Colibacillosis. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine, 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 807–834. [Google Scholar]

- Foley S. L., Lynne A. M., and Nayak R... 2008. Salmonella challenges: prevalence in swine and poultry and potential pathogenicity of such isolates. J. Anim. Sci. 86(14 Suppl):E149–E162. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraile L., Grau-Roma L., Sarasola P., Sinovas N., Nofrarías M., López-Jimenez R., López-Soria S., Sibila M., and Segalés J... 2012. Inactivated PCV2 one shot vaccine applied in 3-week-old piglets: improvement of production parameters and interaction with maternally derived immunity. Vaccine 30:1986–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frana T. S., and Hau S. J... 2019. Staphylococcosis. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine. 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 926–933. [Google Scholar]

- Frank R. K., Chengappa M. M., Oberst R. D., Hennessy K. J., Henry S. C., and Fenwick B... 1992. Pleuropneumonia caused by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae biotype 2 in growing and finishing pigs. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 4:270–278. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto I. R. H., Sonálio K., and de Oliveira L. G... 2019. Atypical porcine pestivirus (APPV) as a new species of pestivirus in pig production. Front. Vet. Sci. 6:35. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt J. T., Tokach M. D., Dritz S. S., DeRouchey J. M., Woodworth J. C., Goodband R. D., and Henry S. C... 2020. Post-weaning mortality in commercial swine production I: review of non-infectious factors. Transl. Anim. Sci. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk M., and Broes A... 2019. Actinobacillosis. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine. 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 749–766. [Google Scholar]

- Grahofer A., Gurtner C., and Nathues H... 2017. Haemorrhagic bowel syndrome in fattening pigs. Porcine Health Manag. 3:27. doi: 10.1186/s40813-017-0074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith R. W., Carlson S. A., and Krull A. C... 2019. Salmonellosis. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine. 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 749–766. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z., Hou C., Sun H., Yang W., Dong J., Bai J., and Jiang P... 2015. Emergence of highly virulent pseudorabies virus in southern China. Can. J. Vet. Res. 79:221–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habrun B., Bilic V., Cvetnic Z., Humski A., and Benic M... 2002. Porcine pleuropneumonia: the first evaluation of field efficacy of a subunit vaccine in Croatia. Vet. Med. (Praha) 47:213–218. doi: 10.17221/5826-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson D. J. 2018a. Distribution and transmission of aetiological agents of swine dysentery. Vet. Rec. 182:192–194. doi: 10.1136/vr.k571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson D. J. 2018b. The spirochete Brachyspira pilosicoli, enteric pathogen of animals and humans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31:e000087-17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00087-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson D. J., and Burrough E. R... 2019. Swine dysentery and brachyspiral colitis. In: Zimmerman J. J., Karriker L. A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K. J., Stevenson G. W., and Zhang J., editors, Diseases of swine, 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Ames, IA; p. 951–970. [Google Scholar]

- Han K., Seo H. W., Oh Y., Park C., Kang I., Jang H., and Chae C... 2013. Efficacy of a piglet-specific commercial inactivated vaccine against Porcine circovirus type 2 in clinical field trials. Can. J. Vet. Res. 77:237–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M. S., Pors S. E., Jensen H. E., Bille-Hansen V., Bisgaard M., Flachs E. M., and Nielsen O. L... 2010. An investigation of the pathology and pathogens associated with porcine respiratory disease complex in Denmark. J. Comp. Pathol. 143:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heibenberger B., Weissenbacher-Lang C., Hennig-Pauka I., Ritzmann M., and Ladinig A... 2013. Efficacy of vaccination of 3-week-old piglets with Circovac against porcine circovirus diseases (PCVD). Trials Vaccinol. 2:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trivac.2013.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp D. J., Kliebenstein J. B., Neumann E. J., Zimmerman J. J., Rotto H. F., Yoder T. K., Whang C., Yeske P. E., Mowrer C. L., and Haley C. A... 2013. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. J. Swine Health Prod. 21:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Holyoake P. K., and Callinan A. P. L... 2006. How effective is Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccination in pigs less than three weeks of age? J. Swine Health Prod. 14:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D., Poljak Z., Farzan A., and Friendship R... 2018. Factors contributing to mortality during a Streptoccocus suis outbreak in nursery pigs. Can. Vet. J. 59:623–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D., Poljak Z., Farzan A., and Friendship R... 2019. Field studies evaluating the direct, indirect, total, and overall efficacy of Streptococcus suis autogenous vaccine in nursery pigs. Can. Vet. J. 60:386–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlen K. P., Dritz S. S., Nietfeld J. C., Henry S. C., Hesse R. A., Oberst R., Hays M., Anderson J., and Rowland R. R... 2008. A field evaluation of mortality rate and growth performance in pigs vaccinated against porcine circovirus type 2. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 232:906–912. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlen K. P., Schneider P., Anderson J., Nietfeld J. C., Henry S. C., Tokach L. M., and Rowland R. R. R... 2007. A cluster of farms experiencing severe porcine circovirus associated disease: clinical features and association with the PCV2b genotype. J. Swine Health Prod. 15:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Lv L., Zhang Z., Xiao Y., and Liu S... 2016. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of pseudorabies in Shandong province of China. J. Vet. Sci. 17:361–368. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2016.17.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacela J. Y., Dritz S. S., DeRouchey J. M., Tokach M. D., Goodband R. D., and Nelssen J. L... 2011. Field evaluation of the effects of a porcine circovirus type 2 vaccine on finishing pig growth performance, carcass characteristics, and mortality rate in a herd with a history of porcine circovirus-associated disease. J. Swine Health Prod. 19:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M., Gerth Löfstedt M., Holmgren N., Lundeheim N., and Fellström C... 2005. The prevalences of Brachyspira spp. and Lawsonia intracellularis in Swedish piglet producing herds and wild boar population. J. Vet. Med. B. Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 52:386–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemersić L., Cvetnić Z., Toplak I., Spicić S., Grom J., Barlic-Maganja D., Terzić S., Hostnik P., Lojkić M., Humski A.,. et al. 2004. Detection and genetic characterization of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in pigs from Croatia. Res. Vet. Sci. 77:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J., Kim S., Park K. H., Kang I., Park S. J., Yang S., Oh T., and Chae C... 2018. Vaccination with a porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccine at 1-day-old improved growth performance of piglets under field conditions. Vet. Microbiol. 214:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J., Park C., Choi K., and Chae C... 2015. Comparison of three commercial one-dose porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) vaccines in a herd with concurrent circulation of PCV2b and mutant PCV2b. Vet. Microbiol. 177:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado C., Paternoster G., Martinez-Lopez B., Burton K., and Mur L... 2019. Could African swine fever and classical swine fever viruses enter into the United States via swine products carried in air pasengers’ luggage? Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 66:166–180. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]