Abstract

There is disproportionate risk for violence conditioned on inequities due to race, socioeconomic status, gender, and where people live. Consequently, some communities are more vulnerable to violence and its repercussions than other communities. This study aims to share indicators that might be useful for violence prevention researchers interested in measuring structural or social determinants that position communities for differential risk of experiencing violence. An existing database of indicators identified in a previous review was reassessed for measures of factors that shape community structures and conditions, which place people at risk for violence. Indicators of 86 community constructs are reported. These indicators may help to advance the field by offering innovative metrics that can be used to investigate further the structural and social determinants that serve as root causes of inequities in violence risk.

Keywords: indicators, primary prevention, public health, risk, social determinants of health, socioeconomic factors, violence

1 |. INTRODUCTION

More than 75 years ago, Shaw and McKay (1942) reported a relationship between the characteristics of communities and the prevalence of juvenile crime and delinquency in Chicago. Since this original research, there have been thousands of studies, from several disciplines, examining indicators and mechanisms explaining the connections between community characteristics and individual behavior. The studies that have focused on violence have established that violence affects all people, at all ages, regardless of race, gender, or socioeconomic status; but some people are at greater risk of violence conditioned on inequities due to race, gender, socioeconomic status, and where people live (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016; Krivo, Peterson, & Kuhl, 2009). Many studies have emerged from this line of research and have contributed to the current understanding of violence, and provided the foundation for contemporary studies on social disorganization theory (Bursik & Grasmick, 1999), social and physical disorder (Skogan, 1992), and collective efficacy and related social processes (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). These theories and concepts have highlighted the demographic characteristics of residents, the social and physical characteristics of the neighborhood environment, and some of the social processes occurring among residents of the most affected neighborhoods, often with the implication that violence is primarily a byproduct of these factors.

To varying degrees, these theories also acknowledge broader issues in the social structure that contribute to the uneven distribution of people and resources. However, it is only relatively recently that public health frameworks have emerged that have focused discussion on systemic marginalization, income inequality, and other structural and social determinants of health that create communities that are stratified based on race and socioeconomic factors (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). In contrast to primarily focusing on the characteristics of neighborhood residents, these frameworks highlight the need to understand and intervene in the structural mechanisms that result in varying communities’ and residents’ differential exposure and vulnerability to violence and its repercussions.

The purpose of this article is to provide a review of indicators that measure the structural conditions that place communities at greater risk for violence. The review is organized using the World Health Organization (WHO) Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequity Framework (SDOH Framework; WHO, 2010) to identify indicators related to the socioeconomic and political context (e.g., macroeconomics and social policies), socioeconomic community conditions (e.g., access to resources, services, and economic opportunities) and the social and physical environment (e.g., crowding and residential segregation). For the purpose of this paper, indicators are defined as observable and measurable metrics (e.g., percentage, number, rate, or other unit) used to measure a community construct related to structural and social determinants of inequity in violence risk. Indicators are value neutral. The interpretation of high or low observations are determined based on theoretical or empirical relationships between the community construct and the outcome of interest.

2 |. BACKGROUND

2.1 |. Social determinants of health equity

The WHO SDOH Framework1 is a conceptual framework that describes the root causes of differences in health and well-being (WHO, 2010). The central elements of the SDOH Framework are the structural determinants of health inequities, which include the socioeconomic context and socioeconomic status; and the intermediary determinants of health, which include material conditions of living and working, behavioral and biological factors, and social factors. The SDOH Framework describes how social, economic, and political factors, such as health, housing, and education policies, affect the socioeconomic positions of people in communities. These disparities in individuals’ socioeconomic positions, in turn, determine the distribution of specific determinants of health (such as living and working conditions, stress) that subsequently and directly impact individual differences in health and well-being. The SDOH Framework also includes feedback loops that represent the nonlinear and iterative nature of social determinants. For example, an individual’s health (outcome) can compromise living and working conditions (intermediate determinants) which may in turn compromise employment opportunities and income (structural determinants).

Many structural and intermediate determinants of health (e.g., income inequality, diminished economic opportunity, and access to mental health or substance abuse services) are also risk or protective factors for multiple forms of violence (Wilkins, Tsao, Hertz, Davis, & Klevens, 2014). For example, income inequality is a risk factor associated with bullying, child abuse and neglect, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and youth violence perpetration (e.g., Eckenrode, Smith, McCarthy, & Dineen, 2014). Diminished economic opportunity, operationalized by measures of concentrated disadvantage and unemployment, is a risk factor associated with child abuse and neglect, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, suicide, and youth violence perpetration (e.g., Pinchevsky & Wright, 2012). Access to mental health and substance abuse services is a protective factor for child abuse and neglect and suicide (e.g., Klevens, Barnett, Florence, & Moore, 2015). Risk and protective factors for violence at the community and societal levels of the social ecology share the same community constructs as structural and intermediate determinants of health in the SDOH Framework. They are a complement to more traditional approaches and frameworks to violence prevention, which have conceptualized each form of violence separately. This shift in focus toward these shared risk and protective factors at the community and societal level (or SDOH) addresses their common “root causes” and provides an opportunity to more efficiently prevent multiple forms of violence (Wilkins, Myers, Kuehl, Bauman, & Hertz, 2018).

2.2 |. Structural violence

The SDOH Framework makes the invisible visible by elucidating the relationship between structural and intermediate determinants of health inequity, and health outcomes. While the SDOH Framework does not explicitly situate violence within its model, other similar concepts, such as structural violence, articulate the links between broader social structures and violent outcomes. Structural violence is described as the invisible, structured social arrangements (i.e., disparate access to resources, political power, education, healthcare) that exclude or marginalize groups of people and normalize some forms of harm as legitimate, making violence ubiquitous or a consequence of “bad” actors (Farmer, Nizeye, Stulac, & Keshavjee, 2006; Scheper-Hughes, 2004). While research to date on the concept, measurement, and consequences of structural violence is fairly sparse, a growing body of research demonstrates a direct association between social and structural determinants of health and violence outcomes (e.g., Benson, Wooldredge, Thistlethwaite, & Fox, 2004; Hipp, 2007; Jogerst, Dawson, Hartz, Ely, & Schweitzer, 2000).

2.3 |. Social and structural determinants of health and structural violence

2.3.1 |. Socioeconomic and political context and violence

Broader socioeconomic and political conditions have been linked to increased rates of multiple forms of violence. For example, higher levels of income inequality (the degree to which income in a given geographic area is distributed equally or unequally) at the county level has been linked to higher rates of child abuse and neglect even when controlling for child poverty (Eckenrode et al., 2014). Income inequality at the census tract level has also been linked to higher rates of violent crime, and this association has been shown to outweigh that of poverty and violent crime (Hipp, 2007). Aspects of the sociopolitical environment have also been measured and linked to violence outcomes. For example, Hatzenbuehler (2011) found that lesbian, gay, and bisexual teens living in counties with a more discriminatory social environment (e.g., lower proportion of schools with antidiscrimination policies that included sexual orientation, etc.) were more likely to report attempting suicide than those living in counties with less discriminatory social environments. These findings demonstrate that socioeconomic and sociopolitical environmental factors shape differential risk for violence.

2.3.2 |. Socioeconomic community conditions and violence

Concentrated disadvantage, affluence, available resources, and related constructs are important for understanding the socioeconomic community conditions that make populations more vulnerable to or protected from violence. Benson et al. (2004), measured neighborhood disadvantage as the percentage of residents who were unemployed, the percentage of single parents, the percentage of households receiving public assistance, and the percentage of residents living below the poverty line in a study of the effects of ecological factors on the perpetration of domestic violence by Black and White men. They found the rates of domestic violence were positively related to neighborhood disadvantage for both groups and that for both races, the rates of domestic violence doubled in neighborhoods with greater disadvantage than neighborhoods with less disadvantage. Conversely, Martinez, Stowell, and Cancino (2008) caution that “focusing on the pernicious effects of concentrated disadvantage is necessary but it may obscure the potential protective effects of affluence” (p. 6). They found, in their study of neighborhood effects on homicide in two border cities, a consistent, positive and significant relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and homicide in both cities and an inverse relationship between affluence (the percentage of the population working in professional occupations) and homicide in one city. Their findings suggest that, at least for one city, the percentage of professionals in a community served as a buffer against violence. The findings supported the theory that relatively affluent neighborhoods have access to social and institutional resources that may help to control violence in their communities.

Available resources in a community provide an important safety net that can reduce violence risk by helping to increase reporting or prevent violence particularly among more vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly (Klein, 2011). For example, Jogerst et al. (2000) found a correlation between available healthcare resources and detection of elder abuse. Specifically, they found that a greater number of hospital beds and nonfederal hospitals were associated with higher levels of reported elder abuse, while those resources plus available primary care physicians, general internists, and chiropractors were strongly associated with higher levels of substantiated elder abuse. Additionally Jogerst et al. (2000) found an effect at the administrative district level served by the Department of Human Services for substantiated elder abuse. The findings suggest that in communities with fewer of these resources available, elder abuse may be underreported and go undetected. These findings, together with the WHO position that the distribution of health services and resources demonstrate the value society places on health in a population (WHO, 2010), highlight the importance of available resources for understanding socioeconomic community conditions and inequities in violence risk.

2.3.3 |. Social and physical environments and violence

The premise of social disorganization theory is that some social and physical structures within communities function as barriers to residents developing collective efficacy through shared values and working to solve shared problems (Kaylen & Pridemore, 2011). The community constructs associated with social disorganization such as residential mobility, residential instability or stability, population density, racial or ethnic heterogeneity, and social and physical disorder have been empirically associated with community violence and violence inequity (Barkan, Rocque, & Houle, 2013; Martinez, Rosenfeld, & Mares, 2008; Wei, Hipwell, Pardini, Beyers, & Loeber, 2005). For example, Barkan et al. (2013) found residential stability helped explain the differences in suicide rates between the western region of the United States and other regions, and across states. The western United States and states with higher suicide rates had lower residential stability. Wei et al. (2005) found physical disorder was significantly and positively associated with rates of crime, firearm injuries and deaths, and teen births, while controlling for concentrated poverty and minority population.

Institutional racism and inequity is another aspect of the social environment that impacts risk for violence. Societal values are reflected in how opportunities are structured and values are assigned to people on the basis of how they look, which unfairly advantages and disadvantages some individuals and communities (Richardson & Norris, 2010). Richardson and Norris (2010), in their review of inequities in access to health and healthcare, used the following definition of racism: “an organized system that categorizes population groups into races and uses this ranking to preferentially allocate societal goods and resources to groups regarded as superior (p. 171).” They defined institutional racism as the, “differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race (p. 171)”; further describing it as normative, sometimes legalized, and manifested in both material living conditions and access to power. Krivo et al. (2009) found, in their study of the influence of citywide racial residential segregation on levels of violent crime, that residential segregation was positively associated with violent crime regardless of the racial/ethnic composition of neighborhoods. However, they found violence risk varied by race due to neighborhood advantage/disadvantage: White residents lived in more advantaged neighborhoods and African Americans and Latinos lived in more disadvantaged communities. Therefore, residential segregation and measures of the dissimilarity index, defined by Borg and Parker (2001) as unevenness in the distribution of racial groups across census tracts within a city, are reflective of the social and physical environments that structure inequities in violence risk.

Social stratification is another aspect of the social environment that has been linked with violence. Social disorganization theory is largely focused on how characteristics of the physical and social environment influence the relationship between collective efficacy (informal social control) and violence (Sampson et al., 1997). Some scholars, such as Borg and Parker (2001), have noted there is less research on how community social structures influence the relationship between formal social control (policing) and violence. In particular, they examined the relationship between community-level stratification (defined as any uneven distribution of the material conditions of existence) and homicide clearance rates (the rate of solved crimes). They found support for the theory that cities with greater levels of inequity (stratification) have higher clearance rates as their results showed police were more likely to solve homicide cases in cities with greater disparities in unemployment, educational attainment, and income between Black and White residents. In addition, police were more likely to solve homicide cases where racial residential segregation was more pronounced. These findings support a theory that greater inequality results in greater formal, governmental social control (policing-type constructs) over the informal social control found in communities with greater advantages.

2.3.4 |. Community dynamics and violence

Policing, social capital, and other forms of social control are community dynamics that bridge social determinants of health with violence outcomes. Kane (2005) found patterns in the relationship between the antecedents of police legitimacy (i.e., police misconduct and inequitable police responsiveness to communities) and violence differed in neighborhoods with low, high, and extreme structurally disadvantaged precincts. In precincts characterized with low structural disadvantage, police legitimacy indicators had no significant effect on violent crime. For highly disadvantaged precincts, police misconduct (defined as a career ending deviance that achieved official organizational recognition (through termination or dismissal), including voluntary resignations or retirements under questionable circumstances) was significantly related to the community risk of experiencing violent crime. Police responsiveness was unrelated to the outcome. For precincts characterized by extreme structural disadvantage, both police misconduct and over-policing (when the mean police responsiveness was higher than the standardized average) predicted increases in violent crime. In summary, the findings support the study author’s assertions that compromised police legitimacy, due to perceived mistreatment and marginalization by police, may lead to increases in violence as some residents in structurally disadvantaged communities cease cooperating with police (Kane, 2005).

The placement of social capital and its related constructs in the SDOH Framework falls between structural and intermediate determinants of health. This placement is in part a reflection of the various definitions of social capital, the implications of those definitions for modifying the effects of intermediate determinants on health outcomes, and the scientific argument that some definitions serve to absolve institutions and governments of responsibility to address inequities (WHO, 2010). However, Lederman, Loayza, and Menendez (2002) found only social capital measuring trust—the belief that most people can be trusted, in community members reduced the incidence of violent crimes. Therefore, in this review, both social capital and collective efficacy (defined as social cohesion among neighbors combined with their willingness to intervene on behalf of the common good; Sampson et al., 1997) are considered protective factors and extensions of trust relationships among individuals, groups, networks, and institutions. Both are considered to be developed and maintained through social circles (social networks) that are occupied as a consequence of socioeconomic status (e.g., education, employment, and wealth).

2.3.5 |. Indicators of structural and social determinants of violence inequity

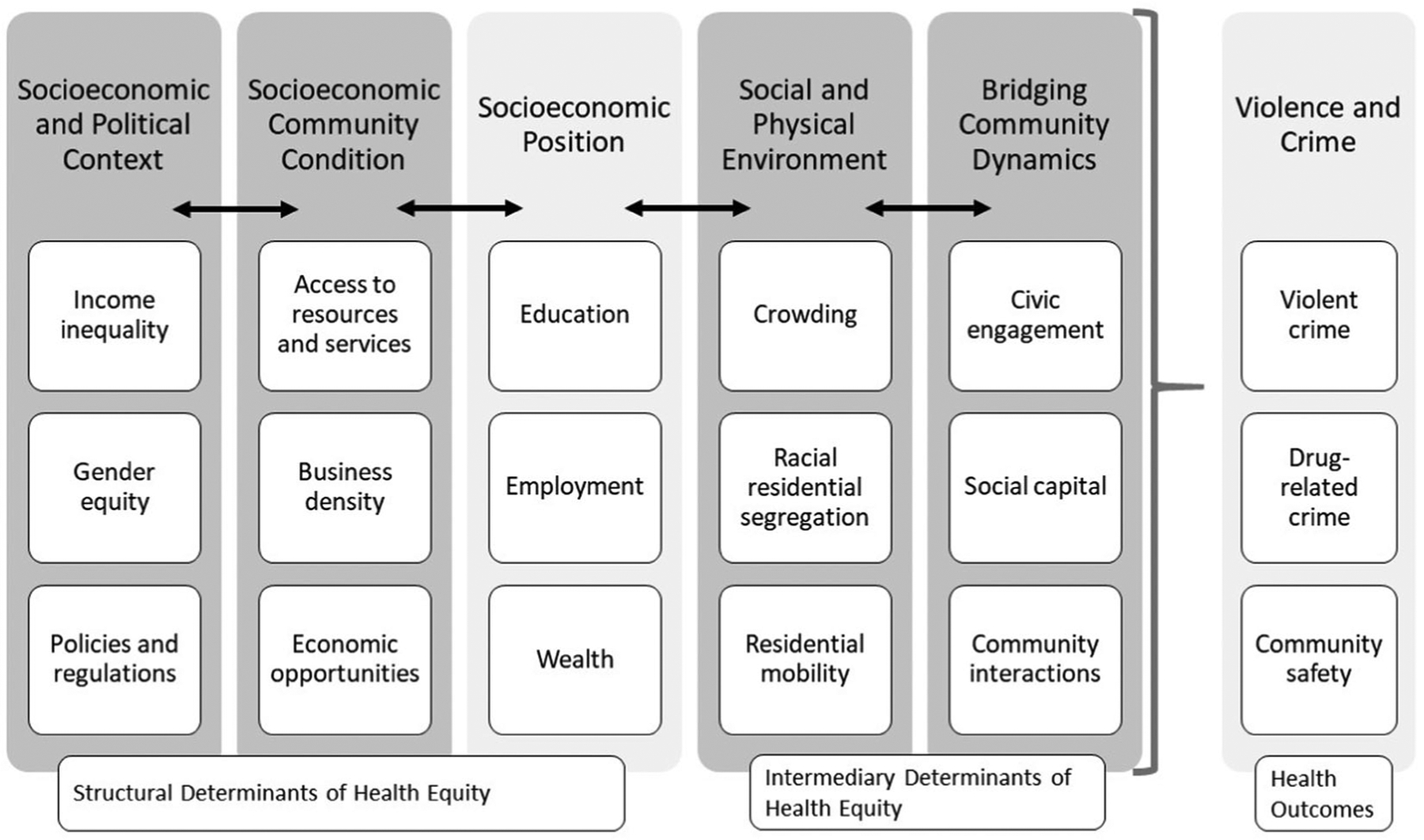

The main goal of this review is to share indicators that might be useful for violence prevention researchers interested in measuring structural or social determinants that position communities at differential risk for violence. Specifically, indicators of community constructs related to structural and social determinants are categorized based on a simplified organization of the SDOH Framework (Figure 1). Similar to the SDOH Framework, the categories of structural and social determinants of violence risk have feedback loops between each determinant of health. The socioeconomic and political context, socioeconomic community condition, and socioeconomic position categories fall within structural determinants of inequities in violence risk. The SDOH Framework describes intermediate determinants as the material circumstances (e.g., living and working conditions) and psychological and behavioral factors that impact equity in health and well-being. Material circumstances reflecting characteristics of the living and working conditions in a community, including aggregated individual characteristics, are reported in the social and physical environment category. Psychological and behavioral factors are individual characteristics that are not addressed in this review.

FIGURE 1.

Structural and social determinant categories and community construct examples (adapted from the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health Framework)

Social cohesion, social capital, and similar concepts fall within the bridging community dynamics category. The latter categories of social and physical environment and bridging community dynamics fall under intermediary determinants of inequities in violence risk. This review is focused on community-level indicators therefore no indicators of socioeconomic position are reported except as part of aggregate measures of constructs in the socioeconomic and political context (e.g., income inequality) or socioeconomic community condition (e.g., concentrated disadvantage) categories. Finally, as the focus of the review is on identifying indicators of determinants of inequities in violence risk, identifying indicators of violence are outside the scope of this review (see Armstead, Wilkins, & Doreson, 2018).

3 |. METHOD

3.1 |. Data source

This review is a secondary analysis that reassesses indicators of community constructs from an existing database (Armstead et al., 2018) for their alignment with social and structural determinants of violence inequities. Data from the original analysis were collected in 2014. The original search returned 2,880 articles, 259 of which met inclusion and exclusion criteria that are relevant for this study. Detailed explanations of the criteria can be found in the previous publication, but in brief, articles reviewed:

were published in peer-reviewed journals,

were published in English using US-based samples,

measured community constructs,

relied on secondary data when using aggregate individual-data,

used data that were available at the state or local level, and

measured a community or societal level risk or protective factor for violence or a related construct.

Some excluded articles (n = 4) in the original review were included in this review because they address important structural determinants of violence inequity, bringing the total number of articles reviewed in this study to 263.

3.2 |. Coding procedure

Indicators were coded according to their alignment with the model in Figure 1 by one reviewer. For each unique community construct only one set of indicators was reported. Preference was given to indicators not previously reported by Armstead et al. (2018). Exceptions were made when there was only one set of indicators for the community construct. While unreported in this article, violence and poverty constructs and their associated indicators can be found in the previous review (Armstead et al., 2018). Poverty is predominantly measured as the percentage or proportion of residents, individuals, or families living below the poverty line. However, community constructs that use poverty indicators, such as deprivation, are reported.

Seven community constructs were excluded because they did not fit the operationalization of structural and social determinants used in this review. Three of the seven were constructs related to harmful gender norms or norms that support aggression (i.e., sexist humor, sexist humor supporting violence against women, and structural stigma of sexual minorities). Although societal values are a central tenet of the SDOH Framework, the placement of noninstitutionalized norms in the framework is unclear. Another three constructs were firearm-related policies (e.g., categories of persons under Federal law who can possess or receive a firearm; child access prevention laws (CAP), which establish criminal penalties for unsecured firearms in the home). These policies also do not fit the operationalization of structural or social determinants used in this review. The final indicator excluded due to a misfit with the use of the framework was a program delivery indicator (i.e., preventive services delivery).

Other reasons why constructs were excluded include the data source, or indicators were unclear or not widely available (n = 9; e.g., crowding, gender social services, healthcare and education access, and inequality in police protection); or the construct validity was weak and not supported in the study in which it was used (n = 1; i.e., instability). In total, indicators of community constructs from 199 articles were excluded. Remaining in the review, and presented in the results tables, are indicators of 86 community constructs from 64 articles (see Table 1). Findings are summarized at the community construct level in the results section and are described in detail in the appendices (i.e., construct, citation, indicators, and data source).

TABLE 1.

Community constructs by social determinants of health

| Socioeconomic and political context (n = 13) | Socioeconomic community conditions (n = 32) | Social and physical environments (n = 25) | Bridging community dynamics (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute racial income inequality (Hipp et al., 2009) | Access to a physician (Youngblade et al., 2006) | Anonymity (Hipp et al., 2009) | Civic engagement (Rosenfeld et al., 2001) |

| Economic conditions related to women’s opportunity costs of keeping children (Bitler & Madeline, 2002) | Access to early care and education services (Klein, 2011) | Concentration of registered sex offenders (Mustaine et al., 2014) | Collective efficacy (Wu, 2009) Communitarian social capital (Gomez & Muntaner, 2005) |

| Economic income inequality (Jacobs & Carmichael, 2002) | Alcohol outlet density Cunradi et al., 2013) | Crime-prone population (Cancino et al., 2009) | Gang concentration (Katz & Schnebly, 2011) |

| Economic inequality (Jacobs & Carmichael, 2001) | Availability of safety net settings (Youngblade et al., 2006) | Disorder incidents (O’Shea, 2006) | Homicide clearance rate (Borg & Parker, 2001) |

| Economic support policies (Flavin & Radcliff, 2009) | Banking and fringe banking (A. M. Lee, Gainey, & Triplett, 2014) | Density of street gang activity (Robinson et al., 2009) | Inequality in police strength (Thacher, 2011) |

| Gender equality (Lei et al., 2014) | Business presence (Browning & Jackson, 2013) | Ethnic heterogeneity (Pizarro & McGloin, 2006) | Informal social control (Martinez et al., 2010) |

| Gender Legislative Equality (Titterington, 2006) | Collective capacity-organization (Borg & Parker, 2001) | Immigration (Martinez et al., 2010) | Institutional social capital (Gomez & Muntaner, 2005) |

| Gender Political Inequality (Titterington, 2006) | Community services (Abrams & Freisthler, 2010) | Neighborhood abandonment (Hipp et al., 2009) | Juvenile arrests (Sugimoto-Matsuda et al., 2012) |

| Gender Socioeconomic Inequality (Titterington, 2006) | Concentrated affluence (Wright et al., 2013) | Neighborhood esthetics (Lovasi et al., 2013) | Neighborhood social interaction/support (Stockdale et al., 2007) |

| Income Inequality (Hipp, 2007) | Economic deprivation (Peterson et al., 2000) | Neighborhood condition (O’Shea, 2006) | Police misconduct (Kane, 2005) |

| Macroeconomic climate (Krivo et al., 2009) | Economic disadvantage (Browning et al., 2010) | Neighborhood dilapidation (Limbos & Casteel, 2008) | Police responsiveness to communities (Kane, 2005) |

| Relative racial income inequality (Hipp et al., 2009) | Economic independence (M. R. Lee, 2008) | Neighborhood heterogeneity (Mares, 2010) | Police use of force (Terrill & Reisig, 2003) |

| Strength of punishment laws (Jacobs & Carmichael, 2001) | Healthcare resources (Jogerst et al., 2000) | Physical environment as a risk factor for crime (Heslin et al., 2007) | Religious Integration (Barkan et al., 2013) |

| Homeownership (Hipp et al., 2009) | Population density (Morenoff et al., 2001) | Social capital (Congdon, 2011) | |

| Index of concentration at the extremes (Morenoff et al., 2001) | Population heterogeneity (Martinez et al., 2008) | Social network, cohesiveness (Silenzio et al., 2009) | |

| Labor market opportunity (Bellair et al., 2003) | Population structure (Messner et al., 2004) | ||

| Local capitalism (M. R. Lee, 2008) | Racial/ethnic concentration (Cubbin et al., 2000) | ||

| Local investment (M. R. Lee, 2008) | Residential instability (Beyer et al., 2013) | ||

| Neighborhood advantage (DuMont et al., 2007) | Residential mobility (Kubrin, 2003) | ||

| Neighborhood economic resources (Hipp et al., 2009) | Residential stability (Li et al., 2010) | ||

| Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2011) | Social and physical disorder (Messer et al., 2013) | ||

| Organizational resources (Stockdale et al., 2007) | Social deprivation (Wu, 2009) | ||

| Police strength (Thacher, 2011) | Social disorganization (Kaylen & Pridemore, 2011) | ||

| Presence of local institutions (Peterson et al., 2000) | Urbanization (Pizarro & McGloin, 2006) | ||

| Race-specific structural disadvantage (Light & Harris, 2012) | Vacancy rate (Papachristos et al., 2013) | ||

| Retail environment/vibrancy (Hipp, 2010) | |||

| Service distribution (Tiefenthaler et al., 2005) | |||

| Services (Gershoff et al., 2009) | |||

| Stratification (Borg and Parker, 2001) | |||

| Underlying community capacities/supports (Kane, 2011) | |||

| Voluntary organizations (Kane, 2011) | |||

| Wealth (Pruchno et al., 2012) |

Source: Adapted from the WHO Social Determinants of Health Framework.

4 |. RESULTS

4.1 |. Socioeconomic and political context

Indicators of 13 community constructs involving the socioeconomic and political context are largely measures of income inequality (n = 5), which is a noted structural determinant of health and a risk factor for multiple forms of violence (see Table A1 for details). Policy-related indicators accounted for two of the reported community constructs. Five community constructs represent institutionalized societal values through indicators of socio-economic, political, education, and legislative opportunities by gender. Finally, indicators of the macroeconomic climate are reported.

4.2 |. Socioeconomic community conditions

Structural disadvantage and all its related constructs typically aggregate modifiable and nonmodifiable individual-level characteristics of people living in communities with measures of economic opportunities or support. Of the 32 community construct indicators reported in the socioeconomic community conditions table, four measured some form of socioeconomic disadvantage or deprivation (see Table A2 for details). Disadvantage consistently included indicators of economic opportunity and deprivation. Deprivation was often simply measured using poverty indicators.

Indicators of three constructs measured economic opportunities at the local level through employment opportunities (including economic independence) and four measured the presence of businesses in communities. Access to medical care, early care and education, substance abuse, housing, recreation, law enforcement and other community services accounted for 12 community constructs indicators in the socioeconomic community conditions table. Of the remaining nine constructs, three measured affluence or advantage, two measured inequities in income distribution or educational resources, and four measured city or resident investment, through homeownership, in the local community.

4.3 |. Social and physical environments

Social disorganization is often measured using a compilation of socioeconomic factors that vary from study to study. Indicators of social disorganization and related constructs account for 20 of the 25 community constructs in the social and physical environments table (see Table A3 for details). Related to the premise of social disorganization theory that some population compositions present a challenge to social cohesion and collective efficacy, three of the remaining community constructs (i.e., concentration of registered sex offenders, crime-prone population, and street gang density) address population composition. Another two are physical environment constructs (i.e., neighborhood esthetics and physical environment as a risk factor for crime).

4.4 |. Bridging community dynamics

Indicators of 16 community constructs reported in the bridging community dynamics table include seven for social capital, collective efficacy, or related constructs (see Table A4 for details). These include different forms of social capital and the availability of neighborhood social support. Six additional community constructs reflect community interactions with law enforcement including homicide clearance rate, juvenile arrests, police responsiveness to communities, and police use of force. The final three constructs are indicators of general and specific social networks and social ties (e.g., gang concentration and religious integration).

5 |. DISCUSSION

Structural and social determinants of health equity are seemingly difficult to influence but the WHO Call to Action (2010) suggests they are modifiable. However, the WHO cautions that addressing social determinants of health alone may reinforce disparities if we do not also address the structural forces that create more or less advantaged population groups due to inequitable distributions of social determinants. Though gender, ethnicity, and cultural background are individual-level determinants of health and are nonmodifiable; communities that are structurally marginalized or isolated based on these factors concentrate advantage or disadvantage along racial and ethnic lines. The fact that communities are structurally marginalized by race and experience concentrated disadvantage has historically made it difficult to separate violence causes from these individual-level determinants of health, especially when the measurement of disadvantage includes race and ethnicity as indicators (Benson et al., 2004). Other challenges with the measurement of disadvantage includes indicators of female-headed single-parent households (Peterson, Krivo, & Harris, 2000). Singling out the gender of single-parent families is problematic from a gender equity perspective. However, single parents are often less economically advantaged than married couples (often with dual incomes; US Census Bureau, 2017).

It must be noted that many of the studies measuring social disorganization theory-related constructs were not using the social disorganization theory framing. In addition, findings related to violence outcomes were mixed even in the presence of other social environmental determinants (e.g., drug activity and violent crime; Martinez et al., 2008). However, for these and all studies reviewed, overall considerations for the differences in the relationships between the community constructs they measure and violence include the type of violence under study, geographical context (e.g., rural vs. urban; Kaylen & Pridemore, 2011), or indicators used to measure the construct. The use of different indicators to measure the same construct across different studies may be due to practical considerations such as data availability or more disciplinary reasons such as differing theories and frameworks across disciplines. The differences in indicators may account for the differences in outcomes across studies measuring the same community constructs. It also suggests a deeper review of the literature is needed to tease out differences in reported outcomes and provide a better understanding of the relationship between structural and social determinants and violence to guide prevention. In addition, more research is needed to assess the strength of the relationships between determinants and violence and to inform how we might intervene to prevent violence from ever occurring in the first place.

5.1 |. Limitations

This literature review relied on an existing indicator database that has several limitations. First, it shares the limitations of Armstead et al. (2018): The literature search was comprehensive but not systematic; the review and the findings were limited to, and have greater applicability in, the United States; the data were collected in 2014 and therefore do not reflect new indicators that have emerged in more recent research literature. Second, the database was limited by the purpose and review criteria of the original review and may not be inclusive of structural and social determinants of inequities in violence risk that are not related to community-level shared risk or protective factors for violence. The shared limitations are a byproduct of conducting secondary data analysis. However, both reviews share the same strength in that the database search in the original review returned over 2,000 articles, which increases confidence in the saturation of potential indicators, especially as the review demonstrated many researchers reuse indicators over time.

Third, having one coder, even with subject matter expertise, decreases the validity of the categorizations because it is unknown whether a different coder would have categorized the community constructs in the same way. One coder also introduces bias and credibility concerns. In recognition of these concerns, and as a precaution, the coder limited the exclusion of community constructs to objective criteria. Constructs were only excluded if the data source for the construct could not be determined, the validity of the construct was not supported in the study it was used, or the WHO Social Determinants of Health Framework did not address it (i.e., social norms). Any exception was documented in the coding procedures. The coder also took process notes to justify every exclusion and promote transparency in decision-making. Finally, and similar to the original review, the indicators found through this review are simply reported as they are used in the research literature with very limited editing and no further guidance is provided on how these indicators may be used in future research or evaluation efforts.

5.2 |. Conclusion

There is little question that exposure to violence and violence risks have health and developmental consequences (Kane, 2011; Li et al., 2010; Messer, Maxson, & Miranda, 2013; Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, & Cartwright, 2012). The indicators from this review and SDOH Framework provide a challenge for the field of violence prevention. Specifically, they prompt questions about the most effective and feasible ways to disrupt the relationships between structural inequities and violence. While there are promising approaches for addressing these structural inequities, there is great need for additional work in this area and strong indicators to measure their effectiveness and build the evidence base. For example, while research suggests that upwardly mobile individuals benefit from socioeconomic and geographic movement (Chetty & Hendren, 2018; McAdoo, 1982), attempts to implement scalable interventions that move individuals out of neighborhoods that expose them to inordinate levels of risk have had mixed outcomes. As illustrated by the “Moving To Opportunity” for fair housing initiative (a 10-year program and research demonstration that moved very low-income families to higher income neighborhood), the effects of this kind of approach are complex and not universally positive (Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2016). In fact, multiple longitudinal studies of this initiative (Chetty et al., 2016; Sanbonmatsu, Kling, Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2006) found that older youth and males did not benefit from the moves, and in some cases experienced iatrogenic effects that involved disrupting many of the mechanisms (e.g., social relationships) that promoted resilience among the participating children and families. This suggests there is still much to be learned regarding the ways in which structural and social factors can be addressed to optimize protection and minimize risk related to violence.

Another approach for addressing structural inequities involves efforts to change neighborhood conditions. Ohmer, Teixeira, Booth, Zuberi, and Kolke (2016), for example, argue for using organizing strategies as a mechanism for promoting collective efficacy among neighborhood residents, a factor shown to be associated with lower levels of neighborhood violence. Community organizing interventions have been successful in gaining social and political power to address several problems that are associated with marginalized neighborhoods, including issues related to policing, food insecurity, and environmental hazards (Bass, 2000; Freudenberg, Pastor & Israel, 2011; Pothukuchi, 2015). Organizing has also been central to initiatives to prevent gun and youth violence (Frattaroli, 2003; Griffith et al., 2008). However, there is limited evidence on the ability to scale these approaches to address the communities that could benefit from intervention, or the variation in how the inequities manifest across those communities. This review might contribute to this literature and practice by suggesting additional levers that community organizers might use to promote change.

Finally, this review provides a reminder that structural and social determinants place communities at different levels of risk for violence but also provides an opportunity for prevention. CDC’s technical packages provide guidance for policymakers on the best available evidence of prevention strategies and approaches that have the potential to address structural and social determinants of violence risk (CDC, 2018). Examples of the approaches included in the technical packages involve policies that strengthen economic supports to families such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, housing stabilization policies, family–friendly work policies, and family assistance policies (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF] and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]). These example approaches address the socioeconomic conditions that place individuals, families, and communities at higher risk for violence (CDC, 2018). The contents of this review provide additional indicators for measuring the impact of such prevention strategies on violence outcomes at a community, county, or state level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

APPENDIX A

TABLE A1.

Socioeconomic and Political Context

| Community constructs | Indicators | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Economic conditions related to women’s opportunity costs of keeping children (Bitler & Madeline, 2002) | The employment-population ratio in the state (number of people employed/number aged 16 and older); unemployment rate; real per capita personal income; real manufacturing wage; real average AFDC benefit per recipient familya | Bureau of Economic Analysis; Bureau of Labor Statistics; US Census |

| Economic income inequality (Jacobs & Carmichael, 2002) | Gini Indexb and ratio of Black-to-White median household incomes | US Census |

| Economic inequality (Jacobs & Carmichael, 2001) | Gini Index | US Census |

| Gender equality (Lei, Simons, Simons, & Edmond, 2014) | Index of female-to-male ratio of those 25 years and older with 4 or more years of college education; the female-to-male ratio of those 16 years and older employed in management, professional, and related occupations; and the female-to-male ratio of income levels | US Census |

| Gender Socioeconomic Inequality (Titterington, 2006) | Index of female-to-male ratio of college completion, female-to-male ratio of fulltime employment, female to male ratio of median income for full-time employees, female to male ratio of employment in professional occupations, and female-to-male ratio of above-poverty level households | Local elected official/congressional data |

| Gender Political Inequality (Titterington, 2006) | Index of female political representation: Total count of female mayor, female county commissioners, female state congressional representation, and female federal congressional representation | US Census |

| Gender Legislative Equality (Titterington, 2006) | Index of the presence of the following: Fair Employment Practices Act (whether women may file lawsuit personally under Fair Employment Practices Act), state passed equal pay laws (women may file lawsuit personally under equal pay laws), sex discrimination law in the area of public accommodations, sex discrimination law in the area of housing, sex discrimination law in the area of financing, sex discrimination law in the area of education, statutes that provide for civil injunction relief for victims of abuse, statutes that define the physical abuse of a family or household member as a criminal offense, statutes that permit warrantless arrest based on probable cause in domestic violence cases, statutes that require data collection and reporting of family violence by agencies that serve these families, statutes that provide funds for family violence shelters or established standards of shelter operations | The Rights of Women Projectc |

| Income Inequality (Hipp, 2007) | Income inequality between racial/ ethnic groups: ratio of white to African American income, ratio white to Latino income (log transformed); | US Census |

| Within-group income inequality: Gini coefficient for family income for each racial/ethnic group, multiplied by the proportion of the tract comprised by each group, and summed | ||

| Economic support policies (Flavin & Radcliff, 2009) | Index of transfer payments: Per capita transfer receipts from federal and state governments to individuals including current transfer receipts of individuals from governments including retirement and disability insurance benefits, medical benefits, income maintenance benefits, unemployment insurance compensation, veterans’ benefits, and education and training assistance; | Bureau of Economic Analysis |

| Index of medical benefits: Per capita federal and state medical benefits transferred to individuals including Medicare and Medicaid benefits, public assistance medical care such as the state children’s health insurance program (SCHIP), and military medical insurance benefits; | ||

| Index of family assistance: Per capita Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC; 1990–1996) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF; 1997–2000) payments | ||

| Macroeconomic climate (Krivo et al., 2009) | Percentage of adult workers employed in manufacturing industries | National Neighborhood Crime Study |

| Relative racial income inequality (Hipp, Tita, & Boggess, 2009) | Difference in logged median income between Latino and African-American households for each tract | US Census |

| Absolute racial income inequality (Hipp et al., 2009) | Absolute value of logged relative racial income inequality | US Census |

| Strength of punishment laws (Jacobs & Carmichael, 2001) | State incarceration rate: Two-year average (after census) of the number prisoners per 100K population and Republican strength | US Census |

Multiple indicators that represent some form of an index are formatted with the prefix “index of”; constructs that are represented by multiple subconstructs are underlined and indices are separated by semi-colons; otherwise, multiple indicators that are not part of an index are separated by commas.

Gini Index/Gini Coefficient is a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent the income distribution of a nation, state, or community’s residents. The coefficient ranges between 0 (complete equality) and 1 (complete inequality).

The indicator can be found using other publicly available data sources (e.g., National Conference of State Legislators and National Women’s Law Center).

TABLE A2.

Socioeconomic community conditions

| Community constructs | Indicators | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Access to a physician (Youngblade, Curry, Novak, Vogel, & Shenkman, 2006) | Statewide distribution of the number of pediatricians, obstetricians/gynecologists, family physicians, adolescent medicine physicians | State Departments of Health |

| Access to early care and education services (Klein, 2011) | Early care and education (ECE) service density: The number of licensed ECE spaces or “‘slots”’ per square mile;a | State Department of Social Services, Community Care Licensing Division; US Census |

| Early care and education supply: The total number of licensed ECE spaces or “‘slots”’ available within a Census tract (supply) minus the number of young children 0–5 years living in the Census tract who have working parents (estimated demand) | ||

| Preschool/nursery school attendance: The percentage of 3- and 4-year-olds regularly attending a “nursery school or preschool” | ||

| Alcohol outlet density (Cunradi, Todd, Mair, & Remer, 2013) | Density of off premise, bars, and restaurants (block-group level of the number of outlets per square kilometer) | State Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission |

| Availability of safety net settings (Youngblade et al., 2006) | Number of community health centers, public substance abuse and family planning clinics | State Department of Health |

| Banking and fringe banking (A. M. Lee, Gainey & Triplett, 2014) | Number and addresses (for geocoding) of payday lenders (and check cashing), pawn shops, and banks | US Census Bureau; City Directories |

| Business presence (Browning & Jackson, 2013) | Mean number of businesses per block face within a tract | Systematic Social Observation Data |

| Collective capacity-organization (Borg & Parker, 2001) | Percentage of city’s expenditures for education; percentage of city’s expenditures for public welfare; percentage of vacant housing units | US Census, City and County Data Book |

| Community services (Abrams & Freisthler, 2010) | The number of services per area for the following types of services: housing (e.g., Low Income—Housing and Urban Development), legal/probation (e.g., correctional-prison-probation), youth services, including those that serve transition age youth (e.g., Youth-Anti-Gang Resources), health services (e.g., AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases), employment (e.g., employment placement and job training), mental health and substance abuse (e.g., counseling, mental health, emotions), education (e.g., education—children, school districts), and general social services (e.g., emergency assistance, basic need) | City Directory of Social Service Agencies |

| Concentrated affluence (Wright, Pratt, Lowenkamp, & Latessa, 2013) | Percentage of adults with a college education, percentage of families with incomes higher than $50,000 (USD), and percentage of the civilian labor force employed in professional or managerial occupations | US Census |

| Economic deprivation (Peterson et al., 2000) | Percentage of the population in poverty, percentage of families headed by females, percentage of civilian noninstitutionalized persons of age 16 and older who are either unemployed or not in the labor force, and percentage of civilian noninstitutionalized persons of age 16 and older who are employed in professional or managerial occupations (reverse coded) | US Census |

| Economic disadvantage (Browning et al., 2010) | Percentage of population age 16–64 who are unemployed or out of the labor force (joblessness), percentage of employed persons 16 and older working in professional or managerial occupations (reverse coded), percentage of the population 25 and older who are college graduates (reverse coded), percentage of households who are female-headed families, percentage of the employed civilian population age 16 and older who work in the six occupations with the lowest average incomes, percentage of population below the poverty line | National Neighborhood Crime Study |

| Economic independence (M. R. Lee, 2008) | The number of family farms in the county per 1,000 people and the proportion of workers that are self-employed; the proportion of workers that work at home | US Department of Agriculture; US Census |

| Healthcare resources (Jogerst et al., 2000) | The number of primary care physicians, family practitioners, general internists, general surgeons, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, physician assistants, chiropractors, hospital beds, and nonfederal hospitals | State Department of Public Health; Office of statewide clinical education programs at the University of Iowa; American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals; State Department of Inspections and Appeals; Physician Assistant Program at the University of Iowa |

| Homeownership (Hipp, Tita, & Greenbaum, 2009) | Proportion of households who own their residences | US Census |

| Index of concentration at the extremes (Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, 2001) | Number of affluent families (income > $50,000/year [USD]) minus the number of poor families (families below the poverty line) divided by the total number of families | US Census |

| Labor market opportunity (Bellair, Roscigno, & McNulty, 2003) | Low-wage service sector: Proportion employed in service and technical, sales, and administrative support; | US Census (county-level) |

| Unemployment: Percentage of adults between 16 and 65 years of age who are not working; | ||

| Professional sector: Proportion employed in managerial and professional specialty occupations; | ||

| Extractive sector: Proportion employed in farming, forestry, and fishing occupations | ||

| Local capitalism (M. R. Lee, 2008) | Index of relative presence of small manufacturing and the proportion of all manufacturing firms in the county that employ less than 20 workers | County Business Patterns from the US Census |

| Local investment (M. R. Lee, 2008) | Proportion of housing units that are owner occupied | Summary File 3 of the 2000 US Census of Population and Housing |

| Neighborhood advantage (DuMont, Widom, & Czaja, 2007) | Percent of owner occupied housing, families with annual incomes of $25,000 (USD) and above, individuals 25 years or older with 4-year college degrees, and individuals 16 years or older working as professionals or managers | US Census |

| Neighborhood economic resources (Hipp et al., 2009) | Median home value for the census tract plus the proportion of population at or below 125% poverty rate | US Census |

| Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (Karriker-Jaffe, Foshee, & Ennett, 2011) | Percentage of people aged 25 and older with less than a high school education, percentage of people aged 16 or older in labor force who were unemployed, percentage of people aged 16 or older who held working-class or blue-collar jobs, percentage of people living below federally defined poverty threshold, percentage of households without access to a car, and percentage of renter-occupied housing units | US Census |

| Organizational resources (Stockdale et al., 2007) | Per capita Alcohol, Drug, Mental health care facilities: Sum of inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance abuse facilities per 100,000 population, including physicians who specialize in mental health, other mental health practitioners, psychiatric and substance abuse hospitals, other specialty mental health hospitals, and residential mental health and substance abuse facilities | ZIP Code Business Patterns data from US Census; US Department of Commerce; InfoUSA (www.infousa.com) |

| Churches: number of churches per 1,000 capita measured at the county level | ||

| Police strength (Thacher, 2011) | Number of police per capita, number of police per index crime, number of police per violent crime | Uniform Crime Reports |

| Presence of local institutions (Peterson et al., 2000) | Number of retail outlets (grocery stores, banks), libraries, and recreation centers | Telephone directory; Directory of city libraries; City Department of Parks and Recreation |

| Race-specific structural disadvantage (Light and Harris, 2012) | Poverty: percentage of county residents below the poverty line by race | Summary Files 1 and 3 from US Census |

| Unemployment: Percentage of the county civilian labor force between the ages of 16 and 59 that is unemployed by race | ||

| Female headship: Percentage of county families with children under 18 years old that are headed by a female by race | ||

| Low education: Percentage of county residents over 25 years old with less than a high school education or equivalent by race | ||

| Retail environment/vibrancy (Hipp, 2010) | Retail employees per capita | US Economic Census |

| Service distribution (Tiefenthaler, Farmer, & Sambira, 2005) | Presence or absence: Number and types of programs and services | National Coalition Against Domestic Violence Directory of Domestic Violence Programs |

| Types of services offered by programs for battered women: Shelter and its capacity, safe home, 24-hour hotline, counseling/advocacy, nonresident support group, children’s programs, sexual assault services, emergency transportation, legal services/advocacy, and counseling for batterers | ||

| Services (Gershoff, Pedersen, & Lawrence Aber, 2009) | Number of recreational facilities (e.g., parks, playgrounds, and libraries), number of protective facilities (e.g., police stations, firehouses, and hospitals) | Geolytics; InfoShare Onlineb |

| Stratification (Borg & Parker, 2001) | Index of the ratio of White to Black educational attainment for those 25+, White household income to Black household income, White to Black unemployment rate, and racial residential segregation | US Census |

| Underlying community capacities/supports (Kane, 2011) | Counts of hospitals and primary care centers; index of schools (K-12 and universities), libraries, neighborhood action groups, recreational facilities, places of worship, and senior citizen centers | US Census (tract-level) |

| Voluntary organizations (Kane, 2011) | Total number per capita within a census tract and type of service per 1,000 population | National Center for Charitable Statistics; Internal Revenue Service’s Business Master File |

| Services include: social services, family services, youth services, economic resources, crime issues, and neighborhood disorder issues | ||

| Wealth (Pruchno et al., 2012) | Percentage with college degree; percentage professionals; number of people with income $150,000 (USD) or greater | US Census |

Multiple indicators that represent some form of an index are formatted with the prefix “index of”; constructs that are represented by multiple subconstructs are underlined and indices are separated by semi-colons; otherwise, multiple indicators that are not part of an index are separated by commas.

Infoshare features New York City and state data only. Indicators are publicly available using online directories.

TABLE A3.

Social and physical environments

| Community constructs | Indicators | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Anonymity (Hipp et al., 2009) | Population density | US Census |

| Concentration of registered sex offenders (Mustaine, Tewksbury, Huff-Corzine, Corzine, & Marshall, 2014) | Number of registered sex offenders divided by the total population of the census tract and multiplied by 1,000 to calculate a standardized rate | Department of Corrections Sex Offender Registry |

| Crime-prone population (Cancino, Martinez, & Stowell, 2009) | Share of population composed of males between ages of 18–34 | US Census |

| Density of street gang activity (Robinson et al., 2009) | Number of African American and Latino street gangs that existed within a 2-mile radius of each zip code’s population-weighted geographic centroid | Ethnographic and observational field research |

| Ethnic heterogeneity (Pizarro & McGloin, 2006) | Number of different ethnic or racial groups that resided in the census tract | US Census |

| Immigration (Martinez, Stowell, & Lee, 2010) | Percent of the population born outside of the United States | US Census |

| Neighborhood abandonment (Hipp et al., 2009) | Proportion of occupied units (reverse coded) | US Census |

| Neighborhood aesthetics (Lovasi et al., 2013) | Sidewalk cafes: Locations of one or more legally operating sidewalk cafes by zip code; | City Department of Consumer Affairs, City Department of Parks and Recreation, and Project Scorecard conducted by Mayor’s Office |

| Street trees: Density of street trees per square kilometer; | ||

| Clean streets: Proportion of streets rated as acceptably clean (as informed by the Department of Sanitation’s standards and public surveys)a | ||

| Neighborhood condition (O’Shea, 2006) | Physical deterioration: e.g., abandoned or unkempt housing | Observational environmental survey |

| Incivilities: e.g., litter and vandalism | ||

| Vulnerability: e.g., dark and empty streets | ||

| Territoriality: e.g., decorating one’s yard or putting one’s name on a door | ||

| Defensible space: e.g., adequate lighting, surveillance opportunities, and barriers to entry | ||

| Disorder incidents (O’Shea, 2006) | Counts of calls for service to respond to shots fired, disorder, fight, harassment, loud noise, and suspicious person or activity | Observational environmental survey |

| Neighborhood dilapidation (Limbos & Casteel, 2008) | Index of visible graffiti, painted over graffiti, litter, cleanliness, dilapidated buildings, and dilapidated streets and sidewalks | Neighborhood environmental survey |

| Neighborhood heterogeneity (Mares, 2010) | Index of the percentage foreign born resident and percentage of the tract population that speaks either an entirely different language or also uses another language on top of English | US Census |

| Physical environment as a risk factor for crime (Heslin, Robinson, Baker, & Gelberg, 2007) | Proximity to skid row, median income, percent of population of racial/ethnic minority backgrounds, percent of land area in industrial use, percent of land area in commercial use, and total population | US Census |

| Population heterogeneity (Martinez et al., 2008) | Latino percentage of the population, percentage of the population who immigrated within the past 10 years, and percentage of households that are “linguistically isolated” | US Census |

| Population density (Morenoff et al., 2001) | Number of persons per square kilometer | US Census |

| Population structure (Messner, Baumer, & Rosenfeld, 2004) | Population size and density | US Census |

| Racial/ethnic concentration (Cubbin, LeClere, & Smith, 2000) | Black: Proportion of all persons who are Black | US Census |

| Hispanic: Proportion of all persons who are Hispanic | ||

| Residential instability (Beyer, Layde, Hamberger, & Laud (2013) | Proportion of individuals living in a different house than they had 5 years before | US Census Bureau and US Department of Agriculture |

| Residential mobility (Kubrin, 2003) | Percentage of persons ages 5 and over who have changed residences in the past 5 years | US Census |

| Residential stability (Li et al., 2010) | Percentage of households staying in the same residence for at least 5 years | US Census |

| Social and physical disorder (Messer, Maxson, & Miranda, 2013) | Housing damage: Boarded door, holes in walls, roof damage, chimney damage, foundation damage, entry damage, door damage, peeling paint, fire damage, condemned, boarded windows, broken windows | Community assessment projectb |

| Security measures: Block-level proportion of security bars, barbed wire, no trespassing signs, beware of dog signs, security signs, and fencing | ||

| Nuisances: Shopping carts, total drug paraphernalia, inoperable car, food garbage, dog waste, tree debris, discarded furniture, discarded appliances, large trash, batteries, condoms, fallen wire, broken manhole cover, uncovered drain, cigarette butts, alcohol container, clothes, baby diapers, construction debris, deep holes, standing water, litter, broken glass, high weeds, graffiti | ||

| Property disorder: Cars on lawn, no grass, standing water, litter, garbage, broken glass, discarded furniture, discarded appliances, discarded tires, inoperable vehicle, high weeds | ||

| Social deprivation (Wu, 2009) | Percentage of foreign-born residents, percentage of linguistic isolation, and percentage of renters in an area | US Census |

| Social disorganization (Kaylen & Pridemore, 2011) | Residential instability: Proportion of households occupied by people who moved from another dwelling in the preceding 5 years | US Census |

| Ethnic heterogeneity: Diversity index calculating the probability of two randomly chosen individuals (from county) being from different ethnic groups | ||

| Family disruption: Ratio of female-headed households to all households with children | ||

| Poverty: Percent of residents living under the poverty level | ||

| Population density: Population at risk for violent victimization (in our case, county populations of those aged 10–17 and 15–24) as a proxy | ||

| Urbanization (Pizarro & McGloin, 2006) | Population size | US Census |

| Vacancy rate (Papachristos, Hureau, & Braga, 2013) | Percentage vacant housing | US Census |

Multiple indicators that represent some form of an index are formatted with the prefix “index of”; constructs that are represented by multiple sub-constructs are underlined and indices are separated by semi-colons; otherwise, multiple indicators that are not part of an index are separated by commas.

Data can be collected through observational assessment.

TABLE A4.

Bridging community dynamics

| Community constructs | Indicators | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Civic engagement (Rosenfeld, Messner, & Baumer, 2001) | Electoral participation: Fraction of the eligible population who voted; | Election Data Book & Elks Membership data |

| Elk Lodge membership: Number of members per 100,000 resident populationa | ||

| Collective efficacy (Wu, 2009) | Average standardized score of the following: percentage of foreign-born residents, percentage of linguistic isolation, and percentage of renters in an area. Higher scores equal weaker collective efficacy | US Census |

| Communitarian social capital (Gomez & Muntaner, 2005) | Bonding relationship with community; bridging relationship between community and government; bridging relationship between community and private developer | Medical archives, historical accounts, past and present newspaper accounts |

| Gang concentration (Katz & Schnebly, 2011) | Count of gang members within each neighborhood | Police gang data |

| Homicide clearance rate (Borg & Parker, 2001) | Average rate over a 3-year period of the number of homicides cleared by an arrest/total number of homicides known to police | FBI Uniform Crime Reports |

| Inequality in police strength (Thacher, 2011) | Ratio of the average police strengthb for agencies serving the 20% of the population in the wealthiest jurisdictions to the average strength for agencies serving the 20% of the population in the poorest jurisdictions | Uniform Crime Reports |

| Informal social control (Martinez et al., 2010) | The neighborhood relative presence of adults per child defined as the ratio of adults (persons aged 18 years and older) to children (persons aged 17 years and younger) | US Census |

| Institutional social capital (Gomez & Muntaner, 2005) | Government support of community housing needs, bridging network between government and private developer; private developer support of community housing needs; ratio of community organizations to population size; relationship between community organizations and institutional entities [accountability vs acceptance]; trust between residents and community organizations; relationship between community organizations and the government [institutional and political support for community residents’ political and economic needs] | Medical archives, historical accounts, past and present newspaper accounts |

| Juvenile arrests (Sugimoto-Matsuda et al., 2012) | Proportion of felony, misdemeanor, petty misdemeanor, violation within the geographic area | Juvenile Justice Information System |

| Neighborhood social interaction/support (Stockdale et al., 2007) | Average household occupancy from U.S. Census was derived by dividing number of persons per square mile by number of occupied housing units per square mile | US Census |

| Police misconduct (Kane, 2005) | Documentation of officers who were dismissed or retired under questionable circumstances who used their employment status to engage in job-specific malpractice (profit-motivated corruption, violence, miscellaneous crimes, administrative misconduct and drug-related crimes) that involved citizens in the communities the officers served | Records analysis of City police data (personnel orders) |

| Police responsiveness to communities (Kane, 2005) | Mean number of violent crime arrests per officer at the precinct level by dividing the number of arrests for violent crimes per precinct by the number of officers assigned to each precinct; standardized by the average number of arrests for violent crime per officer in the low disadvantaged precincts; values lower than the standardized value were under-policed and higher values were over-policed | US Census; City police data |

| Police use of force (Terrill & Reisig, 2003) | Acts that threaten or inflict physical harm on suspects | Field observations |

| Force was ranked in the following manner: none, verbal (commands and threats), physical restraint (pat downs, firm grip, handcuffing), and impact methods (pain compliance techniques, takedown maneuvers, strikes with the body, and strikes with external mechanisms) | ||

| Religious Integration (Barkan et al., 2013) | Percentages of adherents of religious congregations | US Religion Census (Religious Congregations and Membership Study) |

| Social capital (Congdon, 2011) | Index of census response rate (U.S. Census), associational density per capita (CBP), tax-exempt non-profit organizations per capita (NCCS), turnout rates for an election (EAC) | US Census, County Business Patterns, National Center for Charitable Statistics, and US Election Assistance Commission |

| Social network, cohesiveness (Silenzio et al., 2009) | Diameter: Maximum number of individuals who must be passed through on a path connecting any two members of the network; | mySpaceCrawler,(version 6) was used to collect data; Network package (version 1.3) available for R was used to analyze data; Pajek (version 1.17) was used to visualize the data |

| Average connectivity (cohesiveness): Number of paths (social ties) between any two members (more different, redundant paths between two member the greater their connectedness); | ||

| Density (cohesiveness): Number of all social ties in the network/all possible ties if every member was connected to every other member; | ||

| Average nodal degree (popularity): Number of neighboring members of the network to whom a given individual is directly connected; | ||

| Nodal degree distribution: Range in number of direct connections of each member of the network (e.g., 100% connected to one person; 80% connected to three members) |

Multiple indicators that represent some form of an index are formatted with the prefix “index of”; constructs that are represented by multiple sub-constructs are underlined and indices are separated by semi-colons; otherwise, multiple indicators that are not part of an index are separated by commas.

Police strength indicator is found in Table A2.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Abrams LS, & Freisthler B (2010). A spatial analysis of risks and resources for reentry youth in Los Angeles County. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 1, 41–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead TL, Wilkins N, & Doreson A (2018). Indicators for evaluating community- and societal-level risk and protective factors for violence prevention: Findings from a review of the literature. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 24(1), S42–S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan SE, Rocque M, & Houle J (2013). State and regional suicide rates: A new look at an old puzzle. Sociological Perspectives, 56(2), 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bass S (2000). Negotiating change: Community organizations and the politics of policing. Urban Affairs Review, 36(2), 148–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bellair PE, Roscigno VJ, & McNulty TL (2003). Linking local labor market opportunity to violent adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40(1), 6–33. [Google Scholar]

- Benson ML, Wooldredge J, Thistlethwaite AB, & Fox GL (2004). The correlation between race and domestic violence is confounded with community context. Social Problems, 51(3), 326–342. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer KMM, Layde PM, Hamberger LK, & Laud PW (2013). Characteristics of the residential neighborhood environment differentiate intimate partner femicide in urban versus rural settings. The Journal of Rural Health, 29(3), 281–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitler M, & Madeline Z (2002). Did abortion legalization reduce the number of unwanted children? Evidence from adoptions. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34(1), 25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg MJ, & Parker KF (2001). Mobilizing law in urban areas: The social structure of homicide clearance rates. Law & Society Review, 35, 435–466. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Byron RA, Calder CA, Krivo LJ, Kwan M-P, Lee J-Y, & Peterson RD (2010). Commercial density, residential concentration, and crime: Land use patterns and violence in neighborhood context. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(3), 329–357. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, & Jackson AL (2013). The social ecology of public space: Active streets and violent crime in urban neighborhoods. Criminology, 51(4), 1009–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursik RJ Jr., & Grasmick HG (1999). Neighborhoods & Crime. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cancino JM, Martinez R Jr., & Stowell JI (2009). The impact of neighborhood context on intragroup and intergroup robbery: The San Antonio experience. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623(1), 12–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Preventing multiple forms of violence: A strategic vision for connecting the dots. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/strategic_vision.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Technical packages for violence prevention: Using evidence-based strategies in your violence prevention efforts. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/technical-packages.html [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, & Hendren N (2018). The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: Childhood exposure effects. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3), 1107–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Hendren N, & Katz LF (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon P (2011). Spatial path models with multiple indicators and multiple causes: Mental health in US counties. Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Epidemiology, 2(2), 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C (2000). Socioeconomic status and injury mortality: Individual and neighbourhood determinants. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 54(7), 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Todd M, Mair C, & Remer L (2013). Intimate partner violence among California couples: Multilevel analysis of environmental and partner risk factors. Partner Abuse, 4(4), 419–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuMont KA, Widom CS, & Czaja SJ (2007). Predictors of resilience in abused and neglected children grown-up: The role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(3), 255–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J, Smith EG, McCarthy ME, & Dineen M (2014). Income inequality and child maltreatment in the United States. Pediatrics, 133(3), 454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, & Keshavjee S (2006). Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Medicine, 3(10):e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavin P, & Radcliff B (2009). Public Policies and Suicide Rates in the American States. Social Indicators Research, 90(2), 195–209. 10.1007/s11205-008-9252-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frattaroli S (2003). Grassroots advocacy for gun violence prevention: A status report on mobilizing a movement. Journal of Public Health Policy, 24(3–4), 332–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Pastor M, & Israel B (2011). Strengthening community capacity to participate in making decisions to reduce disproportionate environmental exposures. American Journal of Public Health, 101(S1), S123–S130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]