Abstract

Corona virus outbreak started in December 2019, and the disease has been defined by the World Health Organization as a public health emergency. Coronavirus is a source of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) due to complications such as over-coagulation, blood stasis, and endothelial damage. In this study, we report a 26-year-old pregnant woman with coronavirus who was hospitalized with a right ovarian vein thrombosis at Besat Hospital in Sanandaj. Risk classification for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) disease is of crucial importance for the forecast of coronavirus.

Keywords: Deep vein thrombosis, Coronavirus, Pregnant women, Case reports, COVID-19

Highlights

The case presented here is a rare ovarian venous thrombosis (OVT) in a pregnant woman after infection with coronavirus with no evidence of venous thrombosis history in her previous deliveries or medical history.

Imaging techniques such as CT scan and MRI would help in the early detection of some of the rare symptoms of coronavirus and prevent catastrophic complications.

Introduction

A specific type of pneumonia originating from the corona virus (COVID-19) is a very serious infectious disease, and the over-prevalence of the virus has been reported by World Health Organizationas a global public health emergency [1]. In December 2019, in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, the first case of COVID-19 pneumonia was reported, and the disease spread rapidly to other parts of the world [2, 3]. The reproductive number (R0), determined as the expected cases of secondary infectious items produced by an infectious item in a vulnerable population, is reported to 3.77 [4].

Pregnancy is a minor form of immunosuppressant that causes pregnant people more vulnerable to infections caused by viruses, and its complications are even greater with Seasonal flu [5]. Thus, the epidemic of corona virus may have irreversible effects for pregnant people [6]. Coronavirus has been shown to be transmitted from human to human [7], Even in patients and asymptomatic people [8] and the mortality rate is very impressive, especially in the weak, older people with co morbidities [9, 10].

Patients with coronavirus are at increased risk of thrombosis due to their over-coagulation status, blood stasis, and endothelial damage [11]. Ovarian venous thrombosis (OVT) is a very serious and rare disease that can occur at any time. It is more common in the period after childbirth period than in other cases and its incidence occurs in about 1 in 2000–3000 deliveries [12]. More than 80% of the after childbirth thrombosis cases are in the right gonadal vein [13].Clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting and weakness are some of the symptoms of this type of thrombosis.

Because the clinical signs of the disease are vague, it is important to use imaging such as Doppler ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI to prevent catastrophic complications such as sepsis, ovarian infarction, pulmonary embolism and mortality [14]. Recent studies have shown that patients with severe coronavirus are exposed to high concentrations of cytokines such as IL2, IL7, IL10, GCSF, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and TNFα [15]. Despite numerous guidelines for deep venous thrombosis (DVT), rare has been reported in the case of thrombosis in coronavirus patients [16]. In this study, we report a 26-year-old pregnant woman with coronavirus who was hospitalized with a right ovarian vein thrombosis at Besat Hospital in Sanandaj. Risk classification for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) disease is of crucial importance for the forecast of coronavirus.

Case presentation

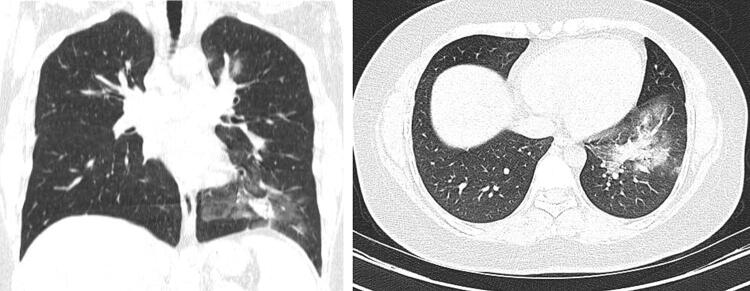

On 2 May 2020, a 26-year-old female, who was 8 weeks pregnant, presented to Besat Hospital in Sanandaj with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting for 1 week. She revealed that none of the health protocols on corona virus has complied. On 5 may, the hospital laboratory reported that the patient’s oropharyngeal swab test results of SARS-CoV-2 by qualitative real-time reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) method was positive. CT scans also show the effects of coronavirus in this patient (Fig. 1). Based on diagnostic protocols, she was confirmed as a patient with coronavirus.

Fig. 1.

Coronal and axial without contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image showing a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection

During the hospitalization, the physical examination of the patient showed a body temperature of 37.4 °C, blood pressure of 96/74 mm Hg, pulse of 89 beats per minute, breathing rate of 27 breaths per minute, and Oxygen saturation of the blood of 95% at 5 L per minute of oxygen. Most routine blood tests, kidney function, electrolyte, and serum procalcitonin were normal. The antigen test for influenza A and B was negative. IgM test to measure influenza A and B was negative. Other laboratory findings are in accordance with Table 1.

Table 1.

The results of laboratory findings

| Test name | Result | Unit | Flag | Reference range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BUN | 7 | mg/dl | Low | 7–16.8 |

| 2 | Ca | 0.8 | mg/dl | Low | 8.6–10.3 |

| 3 | Na(ser) | 135 | mEq/L | Low | 138–145 |

| 4 | Mg | 2.9 | mg/dl | Hi | Female:1.9–2.5 |

| 5 | K(ser) | 3.8 | mEq/L | 3.6–5.9 | |

| 6 | MCH | 18.4 | pg | Low | 27.5–33.2 |

| 7 | MCHC | 28.8 | g/dL | Low | 30.0–38.0 |

| 8 | Plt | 359 | × 1000/µL | 140–440 | |

| 9 | Cr | 0.8 | mg/dl | Female:0.6–1.3 mg/dL | |

| 10 | SGOT(AST) | 123 | IU/L | Female up to 31 | |

| 11 | SGPT(ALT) | 283 | IU/L | Female: < 31 | |

| 12 | WBC | 3.2 | × 1000/µL | Low | 4.4–11 |

| 13 | RBC | 3.75 | × 1,000,000/µL | Low | Female:4.5–5.1 |

| 14 | Hb | 6.9 | g/dl | Low | Female:12.3–15.3 |

| 15 | Hct | 24 | % | Low | Female:36–44.5 |

| 16 | MCV | 64 | fl | 80–96 |

Due to repeated abdominal pain and vomiting, an ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis was taken with a doctor's order. On ultrasound, all abdominal and pelvic organs except the right and left kidneys were reported to be normal. But quite by accident, a vein was seen between the inferior vena cava and the aorta. In the initial studies, gonadal vein thrombosis was suggested.

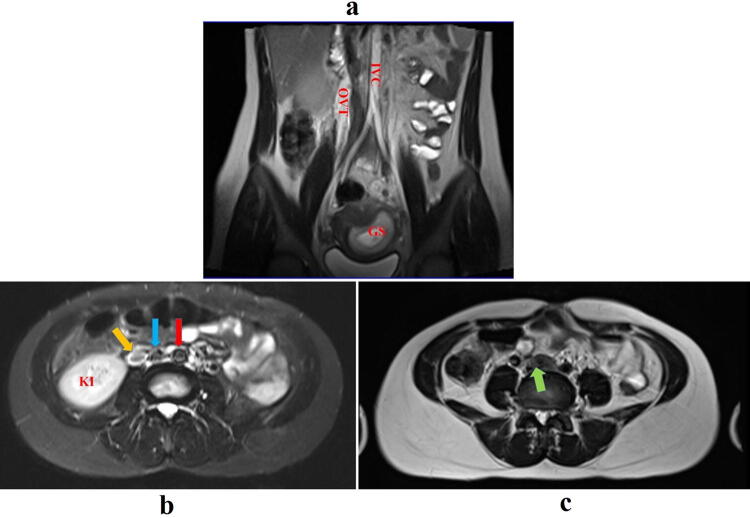

As the patient continued his treatment and more detailed examinations, the MRI was taken from the abdomen and pelvis area. In the examination of T2 MR Images in the axial sections, the distal part of the inferior vena cava was quite prominent with an abnormal signal which to some extent represents the partial vena cava inferior vein thrombosis (Fig. 2c). In these studies, the right and left iliac veins were clearly visible, which could indicate thrombosis in this area. The appearance of a right ovarian vein in MRI images was permanent with signs of increased signal in this area, which indicates ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) (Fig. 2a and b).Also, seeing a gestational sac in the coronal section of Fig. 2 indicates that the patient is pregnant (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Coronal and axial without contrast-enhanced Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image showing a Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT). yellow arrows show ovarian vein thrombosis, red arrows show aorta artery, blue arrows show inferior vena cava and green arrows show inferior vena cava bifurcation; Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT), gestational sac (GS), kidney(KI) and inferior vena cava (IVC) in the abdominal and pelvic sections

Discussion

Some patients, especially the elderly, and those with chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer may be at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or organ dysfunction (MODS) [17, 18]. Many studies have reported that patients with severe COVID-19 should have symptoms such as Respiratory failure with urgent need for a ventilator, shock and impaired activity of other organs [16].

Pathophysiologically, many studies have shown that patients with coronavirus are generally prone to water shortages to venous thrombosis due to fever and diarrhea, hypotension, secondary infections, and prolonged bed rest [19]. So, to reduce the complications and mortality rate from coronavirus, it is essential to assess the risk of deep vein thrombosis.

Therefore, high-risk patients with DVT usually have a number of characteristics, including age over 40 years, respiratory failure, cardiovascular failure, obesity, history of previous thrombosis, acute onset of chronic pulmonary obstruction, acute cerebral infarction, acute coronary artery syndrome, malignant tumors and more than 3 days of bed rest [20].

In this case, the patient had complex obesity and respiratory failure; she has also been in bed for more than three days due to a chronic covid-19 infection. So, for these patients, to prevent the possible events next subsequent thrombosis, initial antithrombotic therapy was considered. It is noteworthy that we did not see any evidence of venous thrombosis in previous deliveries when we examined her previous medical history before COVID-19, and there were no records of the disease in the patient's family. Therefore, it is thought that such acute thrombosis occurred during COVID-19 disease.

Several recent studies have shown that patients with severe coronavirus have high concentrations of cytokines, including IL2, IL7, IL10, GCSF, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and TNFα, which can be related with the severity of the disease and its complications [15]. Our report adds further document in Side effects such as obstruction of veins and arteries in patient with corona virus. Assessment and risk classification for DVT disease are of critical importance for the prognosis of coronavirus disease.

Conclusion

Coronavirus is a source of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) due to complications such as over-coagulation, blood stasis, and endothelial damage. Risk classification for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) disease is of crucial importance for the forecast of coronavirus. With Doppler ultrasound, it is possible to diagnose the disease completely. However, CT and MRI fully confirm the diagnosis if the diagnosis of the disease is uncertain. The main basis of treatment is the conservative tendency whereas the surgical tendency is considered for persistent DVT.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Research Center of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (Mr. Masaood Moradi and Dr. Khalafi) and Besat Hospital in Sanandaj for their cooperation and information collection. Also, this research has been approved by the Research Center of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences with the file number (IR.MUK.REC.1399.019)

Author contributions

MBHS collected the clinical and NHSH wrote the manuscript; SM and AM analyzed the data; MBHS supervised the entire study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests that prejudices the impartiality of this scientific work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhu N, et al., China Novel Coronavirus I, Research T (2020) A Novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 382(8): 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Yang X, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. The Lancet. 2020;395(10226):809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, et al. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: Focus on pregnant women and children. J Infect. 2020;80:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creanga AA, et al. Severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(4):717–726. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d57947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siston AM, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1517–1525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan JF-W, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastola A, et al. The first 2019 novel coronavirus case in Nepal. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(3):279–280. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30067-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang H, Acharya G. Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy: what clinical recommendations to follow? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(4):439–442. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHCotPsRo, C., (2020) New coronavirus pneumonia prevention and control program (seventh trial edition). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml.

- 12.Rottenstreich A, et al. Pregnancy and non-pregnancy related ovarian vein thrombosis: clinical course and outcome. Thromb Res. 2016;146:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougan C, et al. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Obstetrician Gynaecologist. 2016;18(4):291–299. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunnihoo DR, et al. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombophlebitis: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1991;46(7):415–427. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou B, et al. Venous thrombosis and arteriosclerosis obliterans of lower extremities in a very severe patient with 2019 novel coronavirus disease: a case report. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02084-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen N, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai Y, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhai Z, et al. Prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism associated with coronavirus disease 2019 infection: a consensus statement before guidelines. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120:937. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells PS, Forgie MA, Rodger MA. Treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA. 2014;311(7):717–728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]