Before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, over 4000 people were dying from tuberculosis (TB) every day [1]. As with past emergencies [2], the impact of COVID-19 on TB outcomes is a serious cause for concern [3] but is currently unknown. Health system overload, due to high numbers of COVID-19 cases, as well as interventions necessary to limit the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could result in severe reductions in health service availability and access for the detection and treatment of TB cases [4]. However, physical distancing interventions could also limit Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission outside of households, where most transmission occurs [5]. This has not been adequately explored in concurrent work [6–8], and it is currently unclear whether social distancing could compensate for disruptions in TB services, and what the impact of these combined COVID-19 disruption effects on TB burden is likely to be.

Short abstract

Any benefit of social distancing on TB deaths is likely to be outweighed by health service disruption. As such, it is crucially important to maintain and strengthen TB-related health services during, and after, the COVID-19 pandemic. https://bit.ly/30aWZnp

To the Editor:

Before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, over 4000 people were dying from tuberculosis (TB) every day [1]. As with past emergencies [2], the impact of COVID-19 on TB outcomes is a serious cause for concern [3] but is currently unknown. Health system overload, due to high numbers of COVID-19 cases, as well as interventions necessary to limit the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could result in severe reductions in health service availability and access for the detection and treatment of TB cases [4]. However, physical distancing interventions could also limit Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission outside of households, where most transmission occurs [5]. This has not been adequately explored in concurrent work [6–8], and it is currently unclear whether social distancing could compensate for disruptions in TB services, and what the impact of these combined COVID-19 disruption effects on TB burden is likely to be.

We used a mathematical model of TB with an age-specific contact matrix calibrated to data from China, India and South Africa (R.C. Harris, T. Sumner, G.M. Knight, et al.; unpublished results), key high TB burden countries accounting for approximately 40% of global TB cases [1], to estimate the relative impact of reductions in social contacts and health services due to COVID-19 on TB burden. We considered three scenarios for reductions in different forms of social contact, reweighting contact rates between age groups to reflect large reductions in the number of contacts per day occurring in schools (0%, 50%, and 100% in the low, medium, and high scenarios respectively), transport (30%, 60%, 80%) and leisure settings (50%, 70%, 80%), and smaller reductions in contacts occurring in workplaces (20%, 30%, 50%), which are within the range of already observed reductions [9, 10]. We assumed that mean numbers of contacts occurring within home settings did not change, although we did not model households explicitly. We also considered three scenarios for TB health service disruption, which could be a result of a number of factors, such as decreases in diagnostic activities and clinic visits, delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation, and reduced treatment support. These were modelled as reductions in the proportion of incident TB cases detected and detected cases successfully treated: a 20%, 50% or 80% relative reduction in both simultaneously. Although our scenarios are in line with initial evidence on reductions in tested and notified cases [11, 12], we examined a wide range of disruptions here as the scale of these is, as yet, largely unknown. Both reductions in social contact and in health service parameters were implemented from early 2020, and were assumed to last for 6 months. We estimated the cumulative change in TB incidence and deaths over 5 years for each combination of these scenarios compared to a baseline with no change.

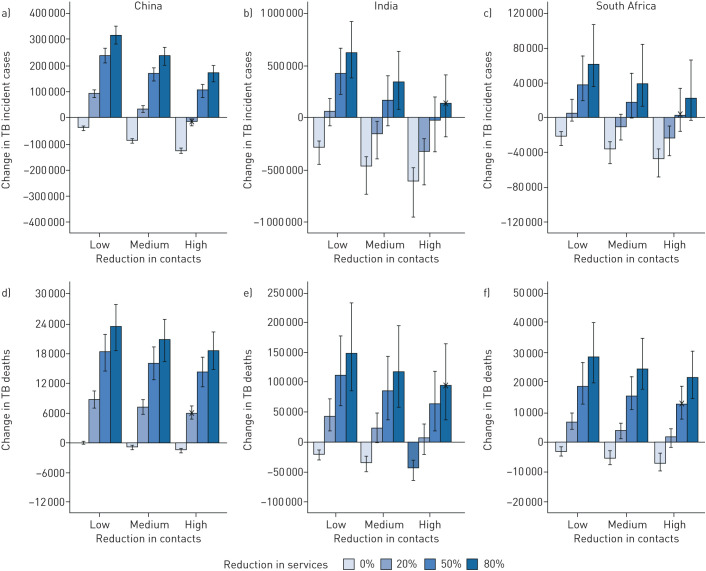

Results suggest that any potential “benefit” of social distancing on TB burden is likely to be larger for TB disease incidence, than for TB deaths (figure 1a–c versus d–f). Such that in some scenarios where health services are less affected, lower numbers of TB cases may occur over this period. However, this is not considered the most plausible scenario based on current anecdotal information in most low- and middle-income settings. In addition, this potential reduction in the impact on TB burden tends not to be true for TB deaths, which show a net increase in deaths in all scenarios with some level of health service disruption. In scenarios with substantial health service disruption, we project an increase in both TB cases and deaths, regardless of the level of social distancing.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative change in tuberculosis (TB) a–c) incidence and d–f) deaths over 5 years as a result of social and/or health system disruption due to the coronavirus 2019 pandemic for a, d) China, b, e) India and c, f) South Africa. Results show the median of model runs, while whiskers denote the range of run results. Small black crosses indicate author assessment of most plausible scenarios based on current anecdotal information. Note y-axis scales differ by country and indicator.

In our worst case scenario, where COVID-19 interventions to reduce social contacts are minimal, but TB health services are badly affected, results suggest an increase in TB deaths of 23 516 (range 18 560–27 940), 149 448 (85 000–233 602) and 28 631 (19 963–40 011) in China, India and South Africa, respectively between 2020–2024, totalling 201 595 (123 523–301 553) additional TB deaths in these three countries alone. This would be an increase of 8–14% in cumulative TB deaths for that period. However, if these countries are able to minimise the impact on TB health service delivery, major reductions in social contacts could keep the number of additional TB deaths comparatively low.

These impacts on TB burden are likely to be felt globally, particularly for TB mortality in the short term. However, our results suggest that the setting-specific nature of the TB epidemic and differences in changing social contacts and service delivery could create highly heterogeneous changes to long-term TB incidence. For example, higher proportions of TB resulting from reactivation in China [13] suggest that reductions in social contacts may have less influence on incidence than elsewhere. Further important factors for consideration include that health service declines are likely to have a greater impact on patients with drug-resistant TB (which we do not consider here). Indeed, a more detailed analysis of health service availability than our simplified consideration of case detection and treatment success, while not yet possible due to the lack of data, is necessary to understand and mitigate for these changes. Our model is also limited in its consideration of each country as a whole, when disruptions are likely to be geographically heterogeneous and specific to local measures. Meanwhile, external factors such as increases in poverty and reductions in access to antiretroviral therapy in settings with a high HIV prevalence could also increase rates of progression to TB disease. In addition, we estimate the impact of a 6-month disruption, but given subsequent pandemic waves are anticipated [14], and are likely to require further mitigation measures, estimates presented here could be considered conservative. Finally, the as-yet-unknown potential for an increase in risk of severe COVID-19 in patients with active or previous TB, as well as an increase in risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, could have major implications for TB burden [15, 16].

It is, however, imperative that continued access to TB diagnosis and care is ensured, together with the collection and regular reporting of TB indicators, to allow the impact on TB to be both measured and mitigated. Research, guidance and funding are urgently required to identify, prioritise and deliver those interventions that could best alleviate the impact of COVID-19-related disruptions. These will differ by timescale. Interventions that are necessarily prioritised during disruptions, such as digital adherence technologies to support patient treatment remotely, will be different to those to prioritised afterwards, such as active case-finding activities focused on the household, where social contacts and transmission may have been concentrated. It is vital that decision-makers and funders recognise the importance of this issue and act to ensure that innovative approaches to people-centred TB care are rapidly scaled up, so that the fight to end one pandemic does not worsen another.

Shareable PDF

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

CMMID COVID-19 Working Group: Petra Klepac, Jon C. Emery, Charlie Diamond, Kathleen O'Reilly, Sam Abbott, Anna M. Foss, Joel Hellewell, Julian Villabona-Arenas, Timothy W. Russell, Christopher I. Jarvis, Samuel Clifford, Billy J. Quilty, Akira Endo, Thibaut Jombart, Alicia Rosello, Kiesha Prem, Graham Medley, Adam J. Kucharski, Stefan Flasche, Hamish P. Gibbs, Gwen Knight, Fiona Yueqian Sun, W. John Edmunds, Yang Liu, Simon R. Procter, Eleanor M. Rees, Sophie R. Meakin, Katherine E. Atkins, Arminder K. Deol, Stéphane Hué, James D. Munday, Quentin J. Leclerc, Emily S. Nightingale, Kevin van Zandvoort, Damien C. Tully, Megan Auzenbergs, Rein M.G.J. Houben, Nikos I. Bosse, Matthew Quaife, Sebastian Funk, Amy Gimma and Carl A.B. Pearson.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.F. McQuaid, R.M.G.J. Houben and R.G. White conceived the study. R.C. Harris performed the modelling. C.F. McQuaid, N. McCreesh, J.M. Read and R.C. Harris performed the data analysis. C.F. McQuaid wrote a first draft of the article. All authors designed the methodology, critiqued the results and contributed to editing the final draft.

Conflict of interest: C.F. McQuaid has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N. McCreesh has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.M. Read has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Sumner has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R.M.G.J. Houben has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R.G. White has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R.C. Harris is an employee of Sanofi-Pasteur.

Support statement: C.F. McQuaid was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (TB MAC OPP1135288). R.G. White and N. McCreesh were funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement that is also part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union (MR/P002404/1) and ESRC (ES/P008011/1). R.G. White was additionally funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (TB Modelling and Analysis Consortium: OPP1084276/OPP1135288; CORTIS: OPP1137034/OPP1151915; Vaccines: OPP1160830) and UNITAID (4214-LSHTM-Sept15; PO 8477-0-600). R.M.G.J. Houben was funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant (action number 757699). The funding sources had no role in the study or decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. Geneva, WHO, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parpia AS, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Wenzel NS, et al. . Effects of response to 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak on deaths from malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis, West Africa. Emerg Infect Dis J 2016; 22: 433. doi: 10.3201/eid2203.150977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wingfield T, Cuevas LE, MacPherson P, et al. . Tackling two pandemics: a plea on World Tuberculosis Day. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 536–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang Y, Liu Y, Du J, et al. . Impact of COVID-19 on tuberculosis control in China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2020; 24: 545–547. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glynn JR, Guerra-Assunção JA, Houben RMGJ, et al. . Whole genome sequencing shows a low proportion of tuberculosis disease is attributable to known close contacts in rural Malawi. PloS One 2015; 10: e0132840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan AB, Jewell B, Sherrard-Smith E, et al. . Report 19 - The Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on HIV, TB and Malaria in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. London, Imperial College London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaziou P. Predicted impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global tuberculosis deaths in 2020. medRxiv 2020; preprint [https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.28.20079582]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stop TB Partnership. The Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Response on tuberculosis in High-burden Countries: a Modelling Analysis. www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/news/Modeling%20Report_1%20May%202020_FINAL.pdf?utm_source=The+Stop+TB+Partnership+News&utm_campaign=4bee55b759-partner+survey+2019_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_75a3f23f9f-4bee55b759-190003997 Date last accessed: 7 Apr 2020.

- 9.Zhang J, Litvinova M, Liang Y, et al. . Age profile of susceptibility, mixing, and social distancing shape the dynamics of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. medRxiv 2020; preprint [https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.19.20039107]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Google. Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports. www.google.com/covid19/mobility/ Date last accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 11.Ismail N, Moultrie H. Impact of COVID-19 Intervention on TB Testing in South Africa. National Institute for Communicable Diseases, 2020. Available from: www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Impact-of-Covid-19-interventions-on-TB-testing-in-South-Africa-10-May-2020.pdf Date last accessed: 20 April, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stop TB Partnership. The TB Response is Heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. http://stoptb.org/news/stories/2020/ns20_014.html Date last updated: 8 Apr 2020.

- 13.Harris RC, Sumner T, Knight GM, et al. . Age-targeted tuberculosis vaccination in China and implications for vaccine development: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e209–e218. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30452-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker PG, Whittaker C, Watson O, et al. . Report 12: The Global Impact of COVID-19 and Strategies for Mitigation and Suppression. London, Imperial College London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tadolini M, Codecasa LR, Garcia-Garcia JM, et al. . Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: first cohort of 49 cases. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motta I, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, et al. . Tuberculosis, COVID-19 and migrants: preliminary analysis of deaths occurring in 69 patients from two cohorts. Pulmonology 2020; 26: 233–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-01718-2020.Shareable (323.6KB, pdf)