SUMMARY

Sleep deprivation (SD) is a common problem in modern societies, which leads to cognitive dysfunctions including attention lapses, impaired working memory, hindering decision making, impaired emotional processing, and motor vehicle accidents. Numerous neuroimaging studies have investigated the neural correlates of SD, but these studies have reported inconsistent results. Thus, we aimed to identify convergent patterns of abnormal brain functions due to acute SD. Based on the preferred reporting for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement, we searched the PubMed database and performed reference tracking and finally retrieved 31 eligible functional neuroimaging studies. Then, we applied activation estimation likelihood meta-analysis and found reduced activity mainly in the right intraparietal sulcus and superior parietal lobule. The functional decoding analysis using the BrainMap database indicated that this region is mostly related to visuospatial perception, memory and reasoning. The significant co-activation of this region using the BrainMap database were found in the left superior parietal lobule, intraparietal sulcus, bilateral occipital cortex, left fusiform gyrus and thalamus. This region also connected with the superior parietal lobule, intraparietal sulcus, insula, inferior frontal gyrus, precentral, occipital and cerebellum through resting-state functional connectivity in healthy subjects. Taken together, our findings highlight the role of superior parietal cortex in SD.

Keywords: Sleep deprivation, Functional neuroimaging, ALE meta-analysis, Intraparietal sulcus, Inferior parietal lobule, Superior parietal lobule

Introduction

Despite the recommended seven to nine hours of sleep per night, people in modern societies are suffering from inadequate sleep [1]. It has been well-documented that insufficient sleep is accompanied with cognitive and emotional impairments [2–4]. Prominently, medical errors, motor vehicle accidents and lower performance are highly prevalent in people with prolonged wakefulness [5,6]. The disintegrations of brain functions due to sleep deprivation (SD), might subsequently precipitate neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders [7].

Thus far, several studies have probed the imbalance activity of brain regions in various cognitive paradigms and imaging modalities due to SD. For example, increasing activity of the default mode network (DMN) and reduced connectivity of different regions in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies has been reported in SD [8]. Moreover, some studies have found aberrant activity of various regions including the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) while subjects are performing various tasks [9–12]. In addition, the neural activity alterations in the nucleus accumbens and ventromedial prefrontal cortex have been reported [3,13]. Meanwhile, extended wakefulness was associated with higher activity of the amygdala, anterior insular and anterior cingulate cortex during emotional paradigm tasks [14]. The findings of positron emission tomography (PET) experiments have illustrated increased activity in the thalamus and insula in SD condition [15,16]. There is also some evidence of structural changes due to SD, such as reduced thickness of the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) [17].

Although the current neuroimaging findings have helped to unravel the brain alterations due to SD, diversity of applied imaging modalities, statistical methods, cognitive tasks, combined with small and heterogeneous sample of individual studies have provided an ambiguous picture of underlying brain abnormality in SD. Hence, a consolidation of the literature is needed to overcome the heterogeneity of previous publications. The aim of this study was to delineate the potential regions of convergent neurobiological abnormalities in SD by quantitatively summarizing the results of available neuroimaging studies. To do so, we have applied Activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis, as a standard algorithm in coordinate-based meta-analyses (CBMA), providing a synoptic view of distributed findings across previous neuroimaging studies on acute SD studies. In particular, ALE algorithm applies a statistical inference by integrating available neuroimaging findings to find “where” in the brain the amount of convergence between reported foci is more than expected by chance [18]. Then, we functionally characterized the obtained consistent regions that have revealed neurobiological aberrations due to SD using the BrainMap database. Moreover, we assessed the task-based and resting-state co-activation patterns to identify the networks that are connected to the identified regions in ALE analysis.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

Following the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines [19], we performed our search in the PubMed database without any restrictions on the date of publications using the search strings: (“sleep deprivation” OR “sleep loss” OR “sleep restriction”) AND (fMRI OR “functional magnetic resonance imaging” OR “voxel-based morphometry” OR “VBM” OR “positron emission tomography” OR “PET”) in January 2018. In the next step, the identified publications have been screened based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) original studies investigating neural correlates of SD on the healthy subjects without any psychiatric or medical conditions; 2) studies using before-after SD protocol or between two groups of subjects with and without SD; 3) studies focusing on acute SD (between 22 and 48 h at once). Our exclusion criteria were the followings: 1) editorial letters, case-reports, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and methodological studies; 2) intervention studies; 3) studies in children/adolescent (<18 y); 4) studies with less than seven subjects; 5) studies that did not perform the whole brain analysis. In particular, we excluded studies using region of interest (ROI) or small volume correction (SVC), as recommended previously [20]; 6) studies that did not report coordinates in the standard brain atlases such as Talairach or Montreal neurological institute (MNI) [21,22]. Then, three independent investigators (N.J., N.S. and K.N.) have extracted and checked all required data including number of subjects, reported peak coordinates (x, y, z) in the standard atlas (Talairach or MNI), contrast of each experiment between SD and normal sleep (NS) (i.e., SD < NS or SD > NS), type of imaging modalities (task fMRI, resting-state fMRI, PET), and task paradigms. Of note, SD has two different types, including acute (e.g., 24–48 h) and partial SD (e.g., 3–4 h of sleep per night for few nights) [23]. We identified three partial SD studies [24–26] and due to different mechanisms in acute versus partial SD and the limited number of such studies for a valid meta-analysis [27], we excluded those with partial SD experiments. Besides, no VBM study was found to be eligible according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic and imaging information of the included papers.

| Author, year | Study design | Number of subjects (before, control/after, case) | Number of female subjects | Age (mean ± standard deviation) | Hours of deprived sleep | Imaging modality | Normalizing Software | Reported standard space | Task | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albouy et al. (2013) [72] | case-control | 16/15 | 14 | 24 ± 3 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | SPM2 | MNI | Motor adaptation task |

| 2 | Benedict et al. (2012) [81] | before-after | 12/12 | 0 | 23.3 ± 0.6 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | MNI | Food stimuli | |

| 3 | Bell-McGinty et al. (2004) [82] | before-after | 15/15 | NS | 25.05 ± 2.7 in 19 subjects | 48 | Task-related fMRI | SPM99 | Talairach | Non-verbal recognition task |

| 4 | Chee et al. (2004) [9] | before-after | 14/14 | 5 | 23 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | Brain Voyager v 4.9 |

Talairach | Verbal working memory |

| 5 | Chee et al. (2008) [10] | before-after | 17/17 | NS | 22.5 ± 1.6 | one night | Task-related fMRI | Brain Voyager QX |

Talairach | S H congruent and incongruent stimuli |

| 6 | Chee et al. (2010) [30] | before-after | 20/20 | 15 | 21.5 ± 2 | one night | Task-related fMRI | Brain Voyager QX |

Talairach | S H congruent and incongruent stimuli |

| 7 | Choo et al. (2005) [31] | before-after | 12/12 | NS | 21.8 ± 0.8 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | Brain Voyager QX |

Talairach | N back |

| 8 | Czisch et al. (2012) [83] | before-after | 20/20 | 19 | 25.5 ± 2.5 | 36 | Task-related fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | Oddball task |

| 9 | Dai et al. (2012) [84] | before-after | 16/16 | 8 | 22 | 24 | Resting-state fMRI | SPM5 | MNI | |

| 10 | Drummond et al. (2005) [85] | before-after | 32/32 | 14 | 27.6 ± 6.6 | 35.7 ± 0.8 | Task-related fMRI | AFNI | Talairach | Verbal learning task |

| 11 | Gao et al. (2015) [86] | before-after | 16/16 | 8 | 22.1 ± 0.8 | 24 | Resting-state fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | |

| 12 | Gujar et al. (2010) [8] | case–control | 12/14 | NS | 22.3 ± 2.8 | 35.2 ± 0.95 | Task-related fMRI | SPM2 | MNI | Memory encoding task |

| 13 | Greer et al. (2016) [87] | case-control | 15/14 | case 10, control 7 | (1) Sleep rested & 10R/10R: n = 7,20.86 ± 2.9 (3) Sleep rested and 9R: n = 8, 19.63 ± 1.2 (2) Sleep deprived and 10R/10R: n = 7, 20.86 ± 1.8 (4) Sleep deprived and 9R: n = 7, 20.57 ± 1.3 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | Monetary incentive delay task trials |

| 14 | Habeck et al. (2004) [88] | case-control | 14/17 | NS | 26.3 ± 4.9 in 18 subjects | 49 | Task-related fMRI | SPM99 | Talairach | Delayed-match-to-sample task |

| 15 | Klumpers et al. (2015) [16] | before-after | 12/12 | 6 | females 29.2 ± 10.2, males 28.5 ± 4.8 | 22 | Task-related fMRI, PET | SPM8 | MNI | Semantic emotional classification |

| 16 | Kong et al. (2012) [12] | before-after | 22/22 | 11 | 20 ± 1.3 | 22 | Task-related fMRI | Brain Voyager QX |

Talairach | Attending face vs. house |

| 17 | Lythe et al. (2012) [89] | before-after | 20/20 | 0 | 26.7 ± 6.7 | 31 | Task-related fMRI | SPM5 | MNI | N back |

| 18 | Menz et al. (2012) [4] | before-after | 22/22 | 0 | 26.6 ± 4.22 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | Risky choice task |

| 19 | Mu et al. (2005) [90] | before-after | 33/33 | 0 | 28.6 ± 6.6 | 30 | Task-related fMRI | SPM2 | MNI | Verbal working memory |

| 20 | Mullin et al. (2013) [3] | before-after | 25/25 | 16 | 23.1 ± 1.6 | 25.5–27 | Task-related fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | Monetary Reward Task |

| 21 | Muto et al. (2012) [11] | before-after | 12/12 | 7 | 21 | 25–33 | Task-related fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | The attentional network task |

| 22 | Rauchs et al. (2008) [91] | before-after | 12/12 | 6 | 23.2 ± 2.9 | 30 | Task-related fMRI | SPM2 | MNI | Virtual environment and navigation tasks |

| 23 | Reichert et al. (2017) [92] | before-after | 31/32 | 18 | 24.68 ± 3.32 | 41 | Task-related fMRI | SPM9 | MNI | Visual n back |

| 24 | Thomas et al. (2003) [15] | before-after | 17/17 | 0 | 24.7 ± 2.8 | 24 | PET | SPM95 | Talairach | Serial addition subtraction task |

| 25 | Vartanian et al. (2014) [93] | before-after | 13/13 | 3 | 32.23 ± 8.45 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | SPM8 | MNI | Divergent thinking task cognitive information processing (AUT) |

| 26 | Vandewalle et al. (2009) [94] | before-after | 15/15, 12/12 | PER3 4/4:7, PER3 5/5:5 | 24.13 ± 0.95 (genotype PER3 4/4), 24.17 ± 1.17 (genotype PER3 5/5) | 25 | Task-related fMRI | SPM5 | MNI | N back |

| 27 | Venkatraman et al. (2007) [2] | before-after | 26/26 | 12 | 21.3 ± 1.6 | 24 | Task-related fMRI | Brain Voyager QX |

Talairach | Gambling task |

| 28 | Venkatraman et al. (2011) [29] | before-after | 29/29 | 14 | 22.34 ± 1.23 | 22 | Task-related fMRI | FSL FEAT 5.63 | Talairach | Decision making |

| 29 | Wang et al. (2016) [95] | before-after | 16/16 | 8 | 24.51 ± 2.75 | 24 | Resting-state fMRI | DPARSF | MNI | |

| 30 | Wu et al. (2006) [96] | before-after | 32/32 | 17 | 28.3 ± 9.4 | 29–34 | PET | SPM99 | Talairach | Visual vigilance task |

| 31 | Xu et al. (2016) [97] | before-after | 22/22 | 9 | 22.5 ± 1.7 | 24 | PET | SPM8 | Talairach | Mathematical processing task |

Importantly, the included studies were mainly assessed for higher activation in SD than NS (SD > NS) or the lower activation in SD compared to NS (SD < NS). We identified several studies with the same/overlapping samples. Therefore, in order to minimize the within group effects, the data was organized by subject groups rather than by specified functional tasks, as suggested before [28]. Similarly, if publications used the same or overlapping group of subjects and reported several experiments, those were combined. Accordingly, we have merged the experiments from various publications [2,9,10,29–31]. Notably, through the entire current study, the word “study” is referred to an individual scientific publication and the word “experiment” is used as a specific contrast (e.g., SD < NS or SD > NS).

Activation likelihood estimation (ALE)

ALE meta-analysis is a canonical CBMA procedure, which is utilized to integrate the reported coordinates from different experiments [28,32,33]. In this approach, the spatial convergence could be described as a consistent functional or structural disturbance [32]. This has been used in various neuropsychiatric conditions [34–40]. In order to identify consistent brain regions related to SD across different experiments, the revised ALE algorithm implemented in MATLAB is utilized here [18]. In the ALE algorithm, the reported foci from experiments were identified as centers for 3D Gaussian probability distribution to consolidate the spatial uncertainty linked to either focus. The width of uncertainty was determined between-subject variations, differences between imaging procedures and normalizing methods. Clearly, the foci of experiments with smaller sample size had a smaller effect on modeled 3D Gaussian probability distributions [18,32]. The probability of all foci of each experiment was then aggregated for each voxel to form a modeled activation (MA) map of every experiment. The unions of modeled activations of all experiments were calculated to obtain an ALE map, which described the convergence of each resulted brain regions. This ALE map was assessed against null-distribution of random spatial association using non-linear histogram integration. Statistical significance threshold was set at p < 0.05 family-wise error at the cluster level (cFWE) to correct for multiple comparisons and avoid false positive findings as suggested previously [20,41]. Each ALE analysis should be conducted if at least 17 experiments are available to achieve 80% power for moderate effects [27]. Anatomy toolbox version 3 [42] and JuBrain cytoarchitectonic atlas (jubrain.fz-juelich.de) were utilized in labeling the observed brain regions [43].

Functional decoding

The region resulting from the ALE analysis was then functionally characterized based on the meta-data from the BrainMap database [42–45], using forward inference, as performed in previous studies [44,45]. The main idea behind this approach is to identify all experiments that activate a particular region of interest and then analyze the experimental meta-data describing the experimental settings that were employed in these areas. This allows statistical inference on the type of tasks that evoke activation in a particular region.

Using the BrainMap database, behavioral domains (BD) are extracted to describe the cognitive processes probed by an experiment. The functional profile of the particular ROI was determined by identifying taxonomic labels for which the probability of finding activation in the respective region/set of regions was significantly higher than the overall chance across the entire database. That is, we tested whether the conditional probability of activation given a particular label [P(Activation|Task)] was higher than the baseline probability of activating the region(s) in question per se [P(Activation)]. Significance was established using the binomial test [p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR)]. Significance (at p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using FDR) was then assessed by means of the chi-squared test.

Task-based and resting-state Junctional connectivity analysis

Both resting-state and task-based FC have been reported in several meta-analyses [34,46,47]. Meta-analytical connectivity modeling (MACM) was used to characterize the whole-brain connectivity of the seed region during the execution of experimental tasks through the identification of significant co-activations with the seed across many individual experiments [32,48]. First, all experiments that feature at least one focus of activation in a particular seed region were identified in the BrainMap database. Next, the retrieved experiments were subjected to a quantitative metaanalysis using the revised ALE algorithm [18,28,32]. This algorithm treats the activation foci reported in the experiments as spatial probability distributions rather than single points, and aims at identifying brain areas that show convergence of activation across experiments. Importantly, convergence was assessed across all the activation foci reported in these experiments. Consequently, any significant convergence outside the seed indicates consistent co-activation and hence FC. Statistical significance was assessed at p < 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons.

We also conducted voxel-wise seed-based FC analysis in a resting-state database of healthy brains, using the regions determined in the ALE analysis as seeds. Seed-based FC analysis assesses synchronous fluctuation of blood oxygen level-dependent signals between the seed and other brain voxels. Here, resting-state fMRI data from 192 healthy adult subjects (65% female, age range 20–75, mean ± SD age = 46.4 ± 16.7 y) from the Nathan Kline Institute/Rockland sample (NKI/Rockland sample) available online via (http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/pro/nki.html) was used [49]. Data were preprocessed in SPM12 and in-house script implemented in MATLAB. The first four scans were excluded prior to further analyses and the remaining EPI images were corrected for head movement using a two-pass (alignment to the initial volume followed by alignment to the mean after the first pass) affine registration. The mean EPI image for each subject was then spatially normalized to the ICBM-152 reference space using the “unified segmentation” approach [50]. The resulting deformation was applied to the individual EPI volumes, which were then smoothed with a 5 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel to improve signal-to-noise ratio and to compensate for residual differences in anatomy. The time-course of each seed region was then extracted per subject by computing the first eigenvariate of the time-series of all voxels within that seed. Variance explained by the mean white matter and cerebral spinal fluid signal were removed from the time-series to reduce spurious correlations. The signal was then band-pass filtered to preserve frequencies between 0.01 and 0.08 Hz. The processed time-course of each seed was then correlated with the time-series of all other gray matter voxels in the brain (identically processed) using Pearson coefficient resulting in the resting-state FC of each seed region. The voxel-wise correlation coefficients were then transformed into Fisher’s Z-scores and were entered in a second-level ANOVA for group analysis including age and gender as covariates of no interest. The results for all three seeds were corrected by cFWE for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05), which have been used in several meta-analyses [34,46,47].

Conjunction between task-based and resting-state Junctional connectivity patterns

We performed conjunction analyses for the identified seed from ALE analysis across task-based and resting-state FC maps to delineate the consensus connectivity patterns, as suggested before [51].

Results

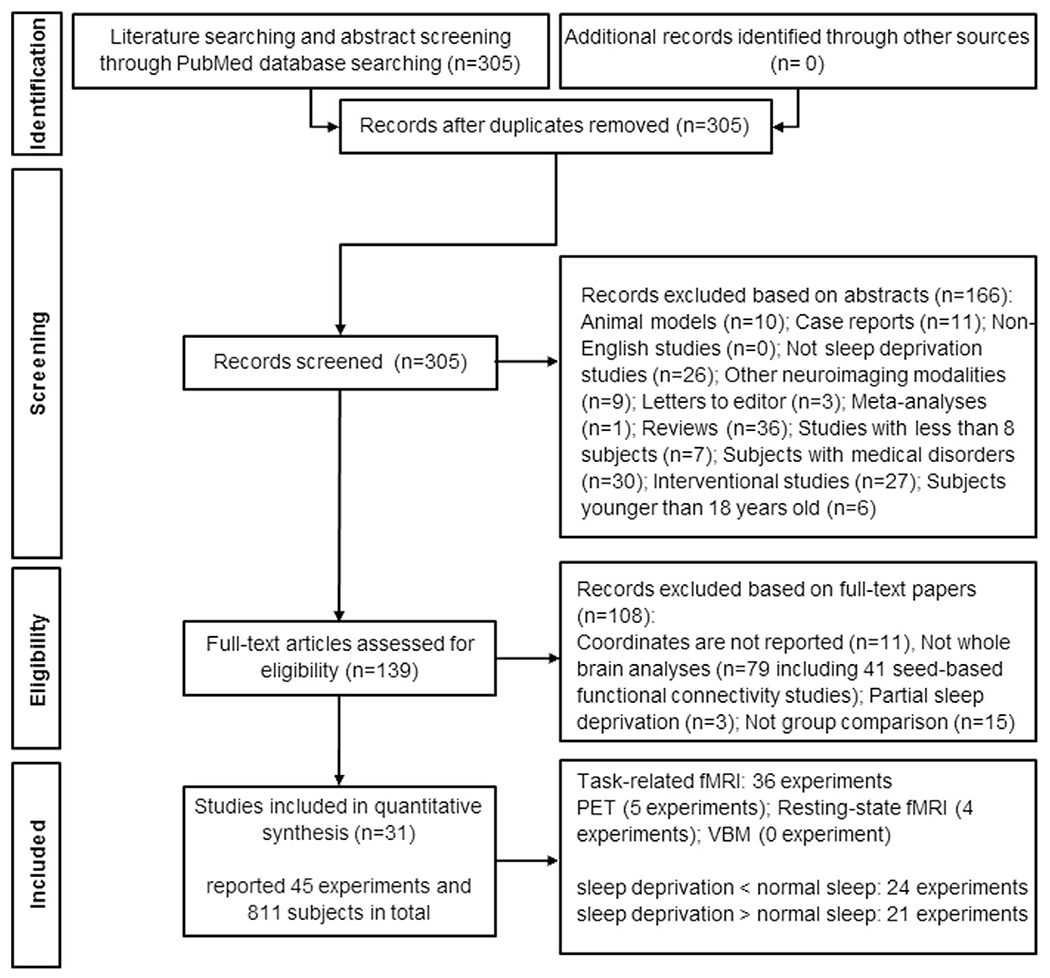

In this meta-analysis, from 305 retrieved papers, 31 studies consisting 45 experiments and 811 subjects were eligible to be included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1, Table 1). These 31 studies included 36 task fMRI, four resting-state fMRI and five PET experiments, which comprised 24 SD > NS and 21 SD < NS experiments.

Fig. 1.

Paper selection strategy flow chart based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement.

Convergence oJ experiments in SD

Testing for significant convergence across all 45 experiments comparing SD and NS conditions, all SD < NS (24 experiments) and all SD > NS (21 experiments) together yielded non-significant results (P = 0.257, cFWE). Separate analyses for all SD < NS or all SD > NS also provided non-significant results (Table S1).

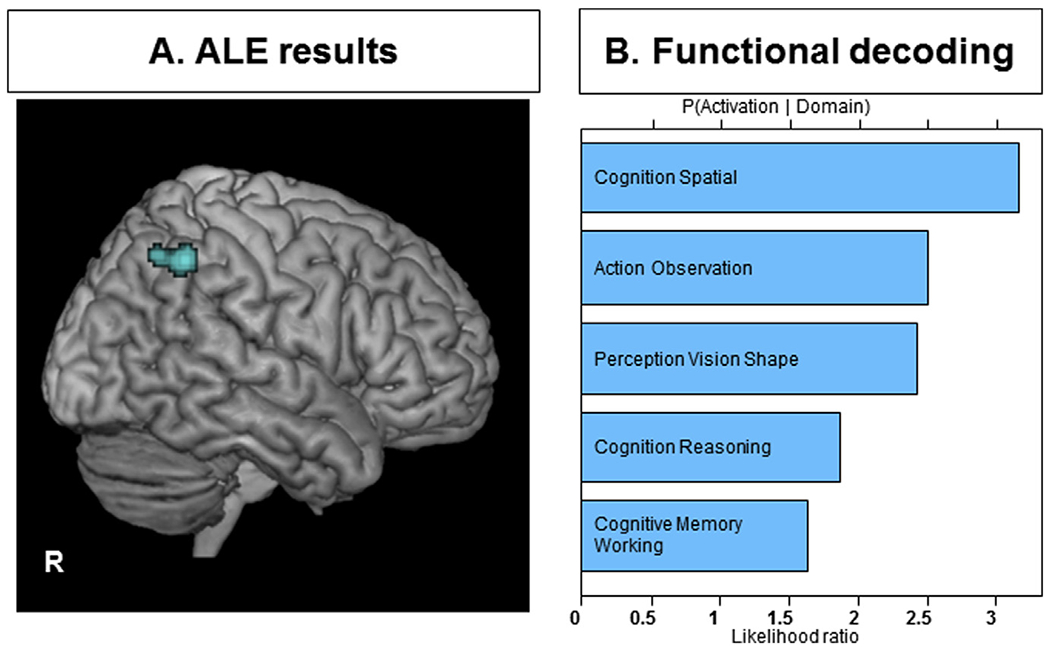

ALE analyses combining resting-state and task fMRI (using only SD < NS condition (20 experiments) demonstrated that subjects with SD had consistent hypoactivity in the superior parietal lobule (SPL), mainly in the right IPS (local maximum: 30–52 48 in MNI space, 98 voxels, P < 0.030, cFWE) (Fig. 2A). In this analysis, seven task-based studies including memory, attention, decision making, and motor tasks contributed and none of the resting-state fMRI experiments contributed here [3,9,10,12,30,31,91]. This region is allocated 66% to the right hIP3 (anterior part of the medial wall of the IPS) using the Anatomy toolbox in SPM (version 3.0) and JuBrain cytoarchitectonic atlas [42,43].

Fig. 2.

A) Convergence of decreased activity in SD compared to NS based on both task and resting-state fMRI experiments in the right intraparietal sulcus and superior parietal lobule. All activations are significant at P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons using the family-wise error rate in cluster level (cFWE); B) behavioral characterization of the significant cluster (p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

Further separate ALE analyses on the 36 task-based fMRI experiments regardless of the contrasts (SD > NS or SD < NS) and 18 task fMRI experiments with the contrast of SD < NS have indicated consistent regional abnormality in the right IPS, mainly in the right hIP3 (P < 0.05, cFWE). Notably, we also combined 41 PET and task fMRI studies and result was not significant (p = 0.198, cFWE). In summary, the reduced activation in the IPS was mainly driven from the task fMRI experiments. More details regarding all sub-analyses are provided in the Supplementary file.

Functional decoding

By applying functional decoding analyses for each seeds (obtained from ALE analyses) in the BrainMap database, we found that these regions were functionally related to cognition (spatial), action (observation), vision-related perception (shape), cognition (reasoning) and cognition (working memory) (p < 0.05, FDR corrected for multiple comparisons) (Fig. 2B).

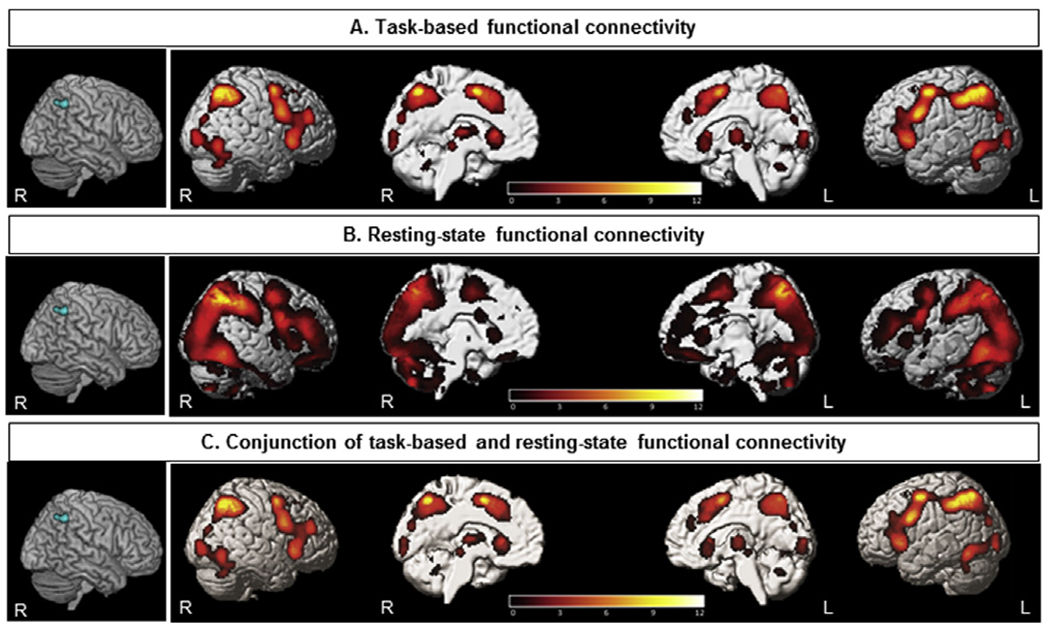

Combined findings of task-based and resting-state functional connectivity analyses

Task-based and resting-state FC analyses have been conducted for the identified regions from ALE analyses (Fig. 3 and Supplementary file). Firstly, the MACM analysis was done in order to identify regions that feature significant task-based co-activation with the seed, based on ALE results from both task and resting-state fMRI experiments in SD < NS experiments. Here, we observed significant co-activation in the hIP3 in IPS [52], hOc4lp (located in caudal and dorsal portions of lateral occipital cortex [53], precentral gyrus [54], insula [55], cerebellum [56] (Fig. 3A). The resting-state FC analysis of the mentioned seed showed significant connectivity with the more extended regions including SPL [57], IPS [52], inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) [58], precentral gyrus [54], insula [55], hOc4lp (located in caudal and dorsal portions of lateral occipital cortex [53], fusiform gyrus [59], cerebellum [56], thalamus [60] (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A) The results of task-based functional connectivity analysis of the seed obtained from ALE findings using the BrainMap dataset; B) the results of resting-state functional connectivity of the seeds obtained from ALE findings in a healthy participants’ dataset; C) conjunction analysis demonstrated regions significantly co-activated with the seed in both task-based and task-independent datasets (p < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons using the family-wise error rate in cluster level (cFWE)).

As the last step, we combined the results of task-based and resting-state FC, which depicted co-activation in the SPL, IPS, insula, IFG, precentral, occipital and cerebellum (Fig. 3C). We also have done the other conjunction analyses combining task-based and resting-state FC related to two other seeds, obtained from ALE analyses on the 36 task fMRI experiments regardless of the contrasts (SD > NS or SD < NS) and 18 task fMRI experiments with the contrast of SD < NS (Supplementary file).

Discussion

We have integrated findings from 31 neuroimaging studies in SD and found convergent reduced activity predominantly in the right intraparietal sulcus and superior parietal lobule. The contribution of this area in the neurocircuitry fingerprint of SD was further explored. The functional decoding analysis indicated possible dysfunction of visual perception, memory and reasoning in SD. The task-based and resting-state FC of this region revealed a network comprising from the left superior parietal lobule, intraparietal sulcus, insula, IFG, precentral, cerebellum, occipital cortex, fusiform gyrus and thalamus.

It has long been known that damage to right parietal regions can cause the hemispatial neglect syndrome, even though this region lacks spatial maps. The findings of our study indicate that there are abnormalities in the right parietal cortex following SD, and, more specifically, they point to altered neural activity in the right IPS and SPL. These two regions are located in the superior parietal cortex (SPC) (Fig. 1), which is known to demonstrate rich, functional heterogeneity across its subregions, including during mnemonic and numerical decision tasks [61]. Its role in a large variety of cognitive tasks, such as spatial attention, perceptual decision making, visual categorization, saccadic eye movements, processing of information in working memory, episodic memory and numerical cognition has been proposed and demonstrated over the years [61]. Our functional decoding analysis has further supported its role in a range of cognitive processes such as spatial cognition, action observation, vision-related perception, reasoning, working memory. More specifically, the co-activation of IPS and SPL in task-based FC analysis was observed to occur with the left SPL, IPS, fusiform gyrus, bilateral occipital cortex and thalamus (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, resting-state FC analysis suggests that underlying functional neurocircuitry may also include the SPL, IPS, IFG, precentral gyrus, insula, occipital cortex, fusiform gyrus, and cerebellum (Fig. 3B). When these results were combined, the co-activation was also suggested in the SPL, IPS, IFG, insula, IFG, precentral, cerebellum, bilateral occipital cortex, left fusiform gyrus and thalamus (Fig. 3C). Taken together, our results point to a multi-component model of SPC functional organization and highlight the central role for IPS and SPL in SD.

The role of superior parietal cortex in sleep deprivation

Following sleep deprivation, our findings suggest abnormal activity in deeper recesses of an anterior part of the medial wall of the IPS and SPL. In that respect, of note are findings of a recent singleneuron study of two tetraplegic subjects. Here, encoding of two types of memory retrieval signals has been demonstrated in this region: familiarity of stimuli, and retrieval confidence [62]. Traditionally, it has been proposed that lateral IPS activity may increase with the familiarity, whilst SPL/medial IPS activity reacts to uncertainty, being stronger when subjects are less confident in their memory decisions. However, findings of Rutishauser and colleagues point to a more complex and richer tapestry of neuronal functional subphenotypes of the region, raising the possibility that this is the critical node where multiple parietal cortex computations enable our choosing of an action—even though the coding of action execution itself may occur somewhere else [63]. Given that our major finding indicates lower activity of both IPS and SPL in sleep deprived subjects, it is then perhaps unsurprising that this region has also been implicated in poorer decision-making in SD people [29]. It is impossible to deduce if demonstrated lower activity in this region is due to a generalized lower activity of all neuronal subpopulations in this region, or if there might be preferential inducement of certain subgroup of neurons, with net lower activity due to significantly reduced activity of other subgroups. Arguably, either scenario might have significant functional repercussion. For example, it has been previously suggested that transient synchronization of theta oscillations across multiple regions, such as retrosplenial cortex may occur during autobiographical memory retrieval, may enable integration of the ground-truth memory-based evidence encoded in medial temporal lobe to SPC regions [64,65]. Similar integration may occur with information from the cerebellum, another region that was suggested to co-activate with IPS and SPL in our study. False and erroneous transfers might be facilitated by sleep deprivation and may underlie some of previously reported sleep deprivation-associated neuropsychiatric deficits. Indeed, dysmetria of thought and affect is now accepted to occur in cerebellar disorders [65]. Thus, improper decision-making observed in SD might be due to the differential pattern of activity in IPS and SPL. Behavioral decoding of this region also indicated the contribution of this region in working memory, observation and reasoning, which may be taken to further support this hypothesis. The other function of IPS is in passive observation and imitation, which might be related to mirror neurons within this region involving in perspective taking [66]. For example, Yamazaki et al. have demonstrated that mirror neurons in this region are involved in encoding the ‘semantic equivalence’ of actions carried out by different agents in different contexts [67]. In this context, IPS connectivity with fusiform gyrus as one of the implicated nodes in the extended SD-affected neurocircuitry is of interest. This region has been considered an important region for semantic representations and the aberrant connectivity with IPS and its subregions may similarly underlie SD driven affective and cognitive deficits. Faulty connectivity with this computational hub for face processing might also lead to functional hypomimia noted in many affective and neuropsychiatric disorders [68].

IPS has long been suggested as a core region of attention network susceptible to SD, for more detailed review of these findings please refer to a recent review on acute SD [69]. For example, findings of a growing body of studies assessing attention paradigms in sleep deprived subjects are in keeping with the notion that the decreased activity of IPS and SPC may be a main culprit that underlies observed delays and poorer results in these individuals [12,63]. Moreover, it is widely thought that the ability to hold information across a delay is necessary to succeed at tasks that require working memory or sustained attention. It is hence of interest that feedback of sustained activity from frontal eye field to IPS within the attention network has been shown gated by task demands [70], with SD lowering this threshold significantly and leading to higher activation in perceptual load of visual processing [71] and visuomotor adaptation [72]. Thus, people with SD are more likely to utilize wider regions of the brain in order to perform optimally, and they may be inclined to perceive tasks as being more complex than those who had sufficient sleep. In that respect it is perhaps of interest to mention the effect of inadequate sleep, and notion of subacute to chronic sleep deprivation through poor sleep efficiency, that forms a severe aspect of most, if not all major sleep disorders. Our group has recently demonstrated the aberrant connectivity of the frontoparietal network, including regions corresponding to IPS and SPL, to severity of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), one of the most prevalent sleep disorders [73]. OSA is commonly associated with poor sleep quality due to frequent arousals during sleep and arguably the aberrant connectivity of attentional network might also lead to executive and neuropsychiatric deficits in some patients with OSA. In keeping, another study has noted that in major depression disorder, there is a lower connectivity of IPS, anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex [74]. Therefore, as the role for IPS and SPL function further emerges, it would be important to address in future studies the complex across-region neural dynamics with different information exchanges at different temporal windows as well as through interactions with broader neural systems, such as our FC analyses suggested.

Potential strengths and limitations

In this study, we found a convergent region across 31 acute SD studies comprising 45 experiments including 811 unique subjects by ALE analysis, following the recent best-practice neuroimaging meta-analysis guideline [20]. Of note, we excluded studies on less than eight subjects, ROI analysis and in order to minimize the within-group effect, we merged the studies with similar sample using pooling approach suggested by Turkeltaub and colleagues [28]. Among 11 included studies in the prior ALE meta-analysis in SD [75], six of the included studies used ROI analysis [13,71,76–79] and we excluded them due to their potential to erroneously skew results regarding any particular ROI [20]. More specifically, null-hypothesis in CBMA utilizes random spatial associations across the whole brain with the assumption that each voxel has the same chance of being activated [80]. Importantly, we used cluster-level FWE with P < 0.05 for multiple comparison correction to maximize the statistical accuracy [20]. Moreover, we performed behavioral characterization of the identified regions using the BrainMap database. Finding a consistent region across whole-brain task-based and resting-state studies enabled us to identify a seed for task-based and resting-state FC analyses in order to delineate regions co-activated with that seed concurrently.

Whilst every effort has been done to follow the best-practice in delivering this study, it has been acknowledged that our findings somewhat differ from the previously published meta-analysis that included a smaller cohort of 11 acute SD studies using “attention tasks” only [75]. Ma and colleagues demonstrated decreased activity in various regions including bilateral IPS, insula, right prefrontal cortex, medial frontal cortex, and right parahippocampal gyrus, as well as increased activity in thalamus [75]. In keeping, our study highlighted the importance of the IPS region, but it did not demonstrate significant changes in other reported regions. Whilst it is possible that the length of sleep deprivation, which in our studies ranged up to 49 h, and different population cohorts and tested paradigms played a role and contributed to differential outcomes, we suggest that different methodologies both groups used could have also contributed to this. For example, a false discovery rate (FDR) correction in GingerALE versions prior to 2.3.6 version, which is used in that work [75], has been reported to have a significant error to control for false positive results and could significantly affect meta-analysis outcomes, which has since been corrected [41].

The level of sample homogeneity required for a CBMA dependents on the research question of each meta-analysis. The optimal approach is to aggregate findings within each task or imaging modality and then integrates the data across them. This requires dividing the available literature into more homogeneous but inevitably also smaller subsets – to the level where valid meta-analyses cannot be carried out on these any longer due to lack of available experiments. On the other hand, including more studies, increases statistical power to detect smaller effects and provide superior evidence for the generalization across experimental and analytical procedures [33]. In the current study, our aim was to identify the spatial convergent abnormality due to sleep deprivation in various task activations and resting-state studies compared to healthy subjects with normal sleep. Of note, there was not enough experiment per task to perform a statistically sound CBMA [27].

Conclusion

Our ALE analyses indicate the reduced activity of the IPS and SPL in SD. Moreover, the functional decoding of IPS and SPL demonstrates several main cognitive functions in visual processing, memory, language, reasoning and spatial recognition. Most excitingly, this very region has recently gained some attention as a potential major hub in modality independent decision making process. We believe that taken together, these findings should inspire future explorations of the role for sleep deprivation and its modulation of the IPS and SPL regions contributions to a diverse array of functional domains and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Material

Practice points.

Our findings have demonstrated a significant convergent functional disruption due to sleep deprivation in the region of the right intraparietal sulcus and superior parietal lobule. In addition, Functional characterization of this region suggested associated dysfunctionality in spatial cognition, observation, visual perception, reasoning and memory.

Connectivity analyses, assessing task-based co-activation and resting-state functional connectivity patterns, have demonstrated that these regions are part of a wider network, also comprising of the left superior parietal lobule, the intraparietal sulcus, insula, inferior frontal gyrus, precentral, occipital cortex, and cerebellum.

This study highlights the important role of parietal cortex in sleep deprivation that should be assessing more in future.

Research agenda.

Future neuroimaging studies should address our findings in larger sample sizes during acute total, as well as acute partial sleep deprivation. Comparison between findings of those experimental paradigms and that underlying subacute and chronic sleep deprivation should enable a more correct deciphering of varied diffuse and focal regional susceptibilities of corresponding neural networks.

Resting-state neuroimaging studies following sleep deprivation should provide a more direct insight into the altered intrinsic organization of major neural networks.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. Simon B. Eickhoff is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH074457), the Helmholtz Portfolio Theme “Supercomputing and Modeling for the Human Brain” and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 7202070(HBP SGA1). Ivana Rosenzweig was supported by the Wellcome Trust [103952/Z/14/Z].

Abbreviations

- ALE

activation likelihood estimation

- cFWE

family-wise error in cluster level

- CMBA

coordinate-based meta-analysis

- dlPFC

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- FC

functional connectivity

- FDR

false discovery rate

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- FWHM

full-width half-maximum

- IPL

inferior parietal lobule

- IPS

intraparietal sulcus

- MA

modeled activation

- MNI

Montreal neurological institute

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- NS

normal sleep

- PCC

posterior cingulate cortex

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PRISMA

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- ROI

region of interest

- SD

sleep deprivation

- SPC

superior parietal cortex

- SPL

superior parietal lobule

- SVC

small volume correction

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.03.008.

References

* The most important references are denoted by an asterisk.

- *[1].Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary 2015;1(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Venkatraman V, Chuah YL, Huettel SA, Chee MWJS. Sleep deprivation elevates expectation of gains and attenuates response to losses following risky decisions 2007;30(5):603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[3].Mullin BC, Phillips ML, Siegle GJ, Buysse DJ, Forbes EE, Franzen PL. Sleep deprivation amplifies striatal activation to monetary reward. Psychol Med 2013;43(10):2215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Menz MM, Buchel C, Peters J. Sleep deprivation is associated with attenuated parametric valuation and control signals in the midbrain during value-based decision making. J Neurosci 2012;32(20):6937–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Khazaie H, Tahmasian M, Ghadami MR, Safaei H, Ekhtiari H, Samadzadeh S, et al. The effects of chronic partial sleep deprivation on cognitive functions of medical residents 2010;5(2):74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Philip P, Åkerstedt T. Transport and industrial safety, how are they affected by sleepiness and sleep restriction? Sleep Med Rev 2006. October;10(5):347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short-and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep 2017. May;9:151–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[8].Gujar N, Yoo SS, Hu P, Walker MP. The unrested resting brain: sleep deprivation alters activity within the default-mode network. J Cogn Neurosci 2010;22(8):1637–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chee MW, Choo WC. Functional imaging of working memory after 24 hr of total sleep deprivation. J Neurosci 2004;24(19):4560–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chee MW, Tan JC, Zheng H, Parimal S, Weissman DH, Zagorodnov V, et al. Lapsing during sleep deprivation is associated with distributed changes in brain activation. J Neurosci 2008;28(21):5519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Muto V, Shaffii-le Bourdiec A, Matarazzo L, Foret A, Mascetti L, Jaspar M, et al. Influence of acute sleep loss on the neural correlates of alerting, orientating and executive attention components. J Sleep Res 2012;21(6):648–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kong D, Soon CS, Chee MW. Functional imaging correlates of impaired distractor suppression following sleep deprivation. Neuroimage 2012;61(1):50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jackson ML, Hughes ME, Croft RJ, Howard ME, Crewther D, Kennedy GA, et al. The effect of sleep deprivation on BOLD activity elicited by a divided attention task. Brain Imaging Behav 2011;5(2):97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Goldstein AN, Greer SM, Saletin JM, Harvey AG, Nitschke JB, Walker MP. Tired and apprehensive: anxiety amplifies the impact of sleep loss on aversive brain anticipation. J Neurosci 2013;33(26):10607–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thomas ML, Sing HC, Belenky G, Holcomb HH, Mayberg HS, Dannals RF, et al. Neural basis of alertness and cognitive performance impairments during sleepiness II. Effects of 48 and 72 h of sleep deprivation on waking human regional brain activity 2003;2(3):199–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Klumpers UM, Veltman DJ, van Tol MJ, Kloet RW, Boellaard R, Lammertsma AA, et al. Neurophysiological effects of sleep deprivation in healthy adults, a pilot study. PLoS One 2015;10(1):e0116906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Elvsashagen T, Zak N, Norbom LB, Pedersen PO, Quraishi SH, Bjornerud A, et al. Evidence for cortical structural plasticity in humans after a day of waking and sleep deprivation. Neuroimage 2017;156:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[18].Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Kurth F, Fox PTJN. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited 2012;59(3):2349–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[20].Muller VI, Cieslik EC, Laird AR, Fox PT, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D, et al. Ten simple rules for neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018;84:151–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging. 1988.

- [22].3D statistical neuroanatomical models from 305 MRI volumes. In: Evans AC, Collins DL, Mills S, Brown E, Kelly R, Peters TM, editors. Nuclear science symposium and medical imaging conference, 1993, 1993 IEEE conference record IEEE; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Philip P, Sagaspe P, Prague M, Tassi P, Capelli A, Bioulac B, et al. Acute versus chronic partial sleep deprivation in middle-aged people: differential effect on performance and sleepiness 2012;35(7):997–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].St-Onge M,Wolfe S, Sy M, Shechter A, Hirsch J. Sleep restriction increases the neuronal response to unhealthy food in normal-weight individuals. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014. March;38(3):411–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].St-Onge MP, McReynolds A, Trivedi ZB, Roberts AL, Sy M, Hirsch J. Sleep restriction leads to increased activation of brain regions sensitive to food stimuli. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95(4):818–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Poudel GR, Innes CR, Jones RD. Distinct neural correlates of time-on-task and transient errors during a visuomotor tracking task after sleep restriction. Neuroimage 2013;77:105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Eickhoff SB, Nichols TE, Laird AR, Hoffstaedter F, Amunts K, Fox PT, et al. Behavior, sensitivity, and power of activation likelihood estimation characterized by massive empirical simulation. Neuroimage 2016;137:70–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[28].Turkeltaub PE, Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Fox M, Wiener M, Fox P. Minimizing within-experiment and within-group effects in activation likelihood estimation meta-analyses. Hum Brain Mapp 2012;33(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Venkatraman V, Huettel SA, Chuah LY, Payne JW, CheeMW. Sleep deprivation biases the neural mechanisms underlying economic preferences. J Neurosci 2011;31(10):3712–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chee MW, Tan JC. Lapsing when sleep deprived: neural activation characteristics of resistant and vulnerable individuals. Neuroimage 2010;51(2):835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Choo WC, Lee WW, Venkatraman V, Sheu FS, Chee MW. Dissociation of cortical regions modulated by both working memory load and sleep deprivation and by sleep deprivation alone. Neuroimage 2005;25(2):579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT. Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: a random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum Brain Mapp 2009. September;30(9):2907–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[33].Tahmasian M, Zarei M, Noori K, Khazaie H, Samea F, Spiegelhalder K, et al. Reply to Hua Liu, HaiCun Shi and PingLei Pan: coordinate based meta-analyses in a medium sized literature: considerations, limitations and road ahead. Sleep Med Rev 2018;42:236–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tahmasian M, Eickhoff SB, Giehl K, Schwartz F, Herz DM, Drzezga A, et al. Resting-state functional reorganization in Parkinson’s disease: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Cortex 2017;92:119–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatr 2015;72(4):305–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tahmasian M, Noori K, Samea F, Zarei M, Spiegelhalder K, Eickhoff SB, et al. A lack of consistent brain alterations in insomnia disorder: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2018;42:111–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tahmasian M, Rosenzweig I, Eickhoff SB, Sepehry AA, Laird AR, Fox PT, et al. Structural and functional neural adaptations in obstructive sleep apnea: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;65:142–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Muller VI, Cieslik EC, Serbanescu I, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB. Altered brain activity in unipolar depression revisited: meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies. JAMA Psychiatr 2017;74(1):47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Giehl K, Tahmasian M, Eickhoff SB, van Eimeren T. Imaging executive functions in Parkinson’s disease: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. 2019. Feb 20. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.02.015. pii: S1353-8020(19)30061-6. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Samea F, Soluki S, Nejati V, Zarei M, Cortese S, Eickhoff SB, et al. Brain alterations in children/adolescents with ADHD revisited: a neuroimaging meta-analysis of 96 structural and functional studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019;100:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[41].Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Fox PM, Lancaster JL, Fox PT. Implementation errors in the GingerALE Software: description and recommendations. Hum Brain Mapp 2017;38(1):7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Eickhoff SB, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Amunts K, et al. A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data 2005;25(4):1325–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zilles K, Amunts K. Centenary of Brodmann’s mapeconception and fate. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11(2):139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Müller VI, Cieslik EC, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB. Dysregulated left inferior parietal activity in schizophrenia and depression: functional connectivity and characterization. Front Hum Neurosci 2013. June 12;7:268 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00268. eCollection 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rottschy C, Caspers S, Roski C, Reetz K, Dogan I, Schulz J, et al. Differentiated parietal connectivity of frontal regions for “what” and “where” memory 2013;218(6):1551–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kohn N, Eickhoff SB, Scheller M, Laird AR, Fox PT, Habel UJN. Neural network of cognitive emotion regulationdan ALE meta-analysis and MACM analysis 2014;87:345–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bzdok D, Langner R, Schilbach L, Engemann DA, Laird AR, Fox PT, et al. Segregation of the human medial prefrontal cortex in social cognition 2013;7:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Laird AR, Eickhoff SB, Rottschy C, Bzdok D, Ray KL, Fox PT. Networks of task co-activations. Neuroimage 2013;80:505–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nooner KB, Colcombe S, Tobe R, Mennes M, Benedict M, Moreno A, et al. The NKI-Rockland sample: a model for accelerating the pace of discovery science in psychiatry 2012;6:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ashburner J, Friston KJJN. Unified segmentation 2005;26(3):839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Nichols T, Brett M, Andersson J, Wager T, Poline J-BJN. Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic 2005;25(3):653–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Choi HJ, Zilles K, Mohlberg H, Schleicher A, Fink GR, Armstrong E, et al. Cytoarchitectonic identification and probabilistic mapping of two distinct areas within the anterior ventral bank of the human intraparietal sulcus 2006;495(1):53–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Malikovic A, Amunts K, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Kujovic M, Palomero-Gallagher N, et al. Cytoarchitecture of the human lateral occipital cortex: mapping of two extrastriate areas hOc4la and hOc4lp. Brain Struct Funct 2016;221(4):1877–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Geyer S, Ledberg A, Schleicher A, Kinomura S, Schormann T, Bürgel U, et al. Two different areas within the primary motor cortex of man. Nature 1996;382(6594):805–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cauda F, Costa T, Torta DME, Sacco K, D’Agata F, Duca S, et al. Meta-analytic clustering of the insular cortex Characterizing the meta-analytic connectivity of the insula when involved in active tasks. Neuroimage 2012;62(1):343–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tellmann S, Bludau S, Eickhoff S, Mohlberg H, Minnerop M, Amunts K. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human brain cerebellar nuclei in stereotaxic space and delineation of their co-activation patterns. Front Neuroanat 2015;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Scheperjans F, Eickhoff SB, H€omke L, Mohlberg H, Hermann K, Amunts K,et al. Probabilistic maps, morphometry, and variability of cytoarchitectonic areas in the human superior parietal cortex 2008;18(9):2141–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Costafreda SG, Fu CH, Lee L, Everitt B, Brammer MJ, David AS. A systematic review and quantitative appraisal of fMRI studies of verbal fluency: role of the left inferior frontal gyrus. Hum Brain Mapp 2006;27(10):799–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lorenz S,Weiner KS, Caspers J, Mohlberg H, Schleicher A, Bludau S, et al. Two new cytoarchitectonic areas on the human mid-fusiform gyrus. Cerebr Cortex 2017;27(1):373–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Woolrich M, Smith S, Wheeler-Kingshott C, Boulby P, et al. Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging 2003;6(7):750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Koenigs M, Barbey AK, Postle BR, Grafman J. Superior parietal cortex is critical for the manipulation of information in working memory. J Neurosci 2009. Nov 25;29(47):14980–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Parvizi J, Wagner AD. Memory, numbers, and action decision in human posterior parietal cortex. Neuron 2018;97(1):7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rutishauser U, Aflalo T, Rosario ER, Pouratian N, Andersen RAJN. Single-neuron representation of memory strength and recognition confidence in left human posterior parietal cortex 2018;97(1):209–20.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Foster BL, Kaveh A, Dastjerdi M, Miller KJ, Parvizi J. Human retrosplenial cortex displays transient theta phase locking with medial temporal cortex prior to activation during autobiographical memory retrieval. J Neurosci 2013. June 19;33(25):10439–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Buckner RLJN. The cerebellum and cognitive function: 25 y of insight from anatomy and neuroimaging 2013;80(3):807–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Caspers S, Zilles K, Laird AR, Eickhoff SBJN. ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain 2010;50(3):1148–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Yamazaki Y, Yokochi H, Tanaka M, Okanoya K, Iriki A. Potential role of monkey inferior parietal neurons coding action semantic equivalences as precursors of parts of speech. Soc Neurosc 2010;5(1):105–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mergl R, Mavrogiorgou P, Hegerl U, Juckel G. Neurosurgery, Psychiatry. Kinematical analysis of emotionally induced facial expressions: a novel tool to investigate hypomimia in patients suffering from depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76(1):138–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[69].Krause AJ, Simon EB, Mander BA, Greer SM, Saletin JM, Goldstein-Piekarski AN, et al. The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017;18(7):404–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Offen S, Gardner JL, Schluppeck D, Heeger DJ. Differential roles for frontal eye fields (FEFs) and intraparietal sulcus (IPS) in visual working memory and visual attention. J Vis 2010. September 29;10(11):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kong D, Soon CS, Chee MW. Reduced visual processing capacity in sleep deprived persons. Neuroimage 2011;55(2):629–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Albouy G, Vandewalle G, Sterpenich V, Rauchs G, Desseilles M, Balteau E, et al. Sleep stabilizes visuomotor adaptation memory: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Sleep Res 2013;22(2):144–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Khazaie H, Veronese M, Noori K, Emamian F, Zarei M, Ashkan K, et al. Functional reorganization in obstructive sleep apnoea and insomnia: a systematic review of the resting-state fMRI 2017;77:219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Crowther A, Smoski MJ, Minkel J, Moore T, Gibbs D, Petty C, et al. Resting-state connectivity predictors of response to psychotherapy in major depressive disorder 2015;40(7):1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[75].Ma N, Dinges DF, Basner M, Rao H. How acute total sleep loss affects the attending brain: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Sleep 2015;38(2):233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chee MW, Tan JC, Parimal S, Zagorodnov V. Sleep deprivation and its effects on object-selective attention. Neuroimage 2010;49(2):1903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Lim J, Tan JC, Parimal S, Dinges DF, Chee MW. Sleep deprivation impairs object-selective attention: a view from the ventral visual cortex. PLoS One 2010;5(2):e9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Mander BA, Reid KJ, Baron KG, Tjoa T, Parrish TB, Paller KA, et al. EEG measures index neural and cognitive recovery from sleep deprivation. J Neurosci 2010;30(7):2686–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Tomasi D, Wang RL, Telang F, Boronikolas V, Jayne MC, Wang GJ, et al. Impairment of attentional networks after 1 night of sleep deprivation. Cerebr Cortex 2009;19(1):233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Turkeltaub PE, Eden GF, Jones KM, Zeffiro TAJN. Meta-analysis of the functional neuroanatomy of single-word reading: method and validation 2002; 16(3):765–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Benedict C, Brooks SJ, O’Daly OG, Almen MS, Morell A, Aberg K, et al. Acute sleep deprivation enhances the brain’s response to hedonic food stimuli: an fMRI study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97(3):E443–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bell-McGinty S, Habeck C, Hilton HJ, Rakitin B, Scarmeas N, Zarahn E, et al. Identification and differential vulnerability of a neural network in sleep deprivation. Cerebr Cortex 2004;14(5):496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Czisch M, Wehrle R, Harsay HA, Wetter TC, Holsboer F, Samann PG, et al. On the need of objective vigilance monitoring: effects of sleep loss on target detection and task-negative activity using combined EEG/fMRI. Front Neurol 2012;3:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Dai XJ, Gong HH, Wang YX, Zhou FQ, Min YJ, Zhao F, et al. Gender differences in brain regional homogeneity of healthy subjects after normal sleep and after sleep deprivation: a resting-state fMRI study. Sleep Med 2012;13(6):720–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Drummond SP, Meloy MJ, Yanagi MA, Orff HJ, Brown GG. Compensatory recruitment after sleep deprivation and the relationship with performance. Psychiatr Res 2005;140(3):211–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Gao L, Bai L, Zhang Y, Dai XJ, Netra R, Min Y, et al. Frequency-dependent changes of local resting oscillations in sleep-deprived brain. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0120323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Knutson B, Walker MP. A genetic polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter determines the impact of sleep deprivation on brain responses to rewards and punishments. J Cogn Neurosci 2016;28(6):803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Habeck C, Rakitin BC, Moeller J, Scarmeas N, Zarahn E, Brown T, et al. An event-related fMRI study of the neurobehavioral impact of sleep deprivation on performance of a delayed-match-to-sample task 2004;18(3):306–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Lythe KE, Williams SC, Anderson C, Libri V, Mehta MA. Frontal and parietal activity after sleep deprivation is dependent on task difficulty and can be predicted by the fMRI response after normal sleep. Behav Brain Res 2012;233(1):62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Mu Q, Nahas Z, Johnson KA, Yamanaka K, Mishory A, Koola J, et al. Decreased cortical response to verbal working memory following sleep deprivation 2005;28(1):55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Rauchs G, Orban P, Schmidt C, Albouy G, Balteau E, Degueldre C, et al. Sleep modulates the neural substrates of both spatial and contextual memory consolidation. PLoS One 2008;3(8):e2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Reichert CF, Maire M, Gabel V, Viola AU, Gotz T, Scheffler K, et al. Cognitive brain responses during circadian wake-promotion: evidence for sleep-pressure-dependent hypothalamic activations. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Vartanian O, Bouak F, Caldwell JL, Cheung B, Cupchik G, Jobidon ME, et al. The effects of a single night of sleep deprivation on fluency and prefrontal cortex function during divergent thinking. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;8:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Vandewalle G, Archer SN,Wuillaume C, Balteau E, Degueldre C, Luxen A, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging-assessed brain responses during an executive task depend on interaction of sleep homeostasis, circadian phase, and PER3 genotype. J Neurosci 2009;29(25):7948–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Wang L, Chen Y, Yao Y, Pan Y, Sun Y. Sleep deprivation disturbed regional brain activity in healthy subjects: evidence from a functional magnetic resonance-imaging study. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat 2016;12:801–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Wu JC, Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, Chen P, Keator DB, Khosla Wu N, et al. Frontal lobe metabolic decreases with sleep deprivation not totally reversed by recovery sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(12):2783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Xu J, Zhu Y, Fu C, Sun J, Li H, Yang X, et al. Frontal metabolic activity contributes to individual differences in vulnerability toward total sleep deprivation-induced changes in cognitive function. J Sleep Res 2016;25(2):169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.