Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to determine the association between mobility, self-care, cognition, and caregiver support and 30-day potentially preventable readmissions (PPR) for individuals with dementia.

Design:

This retrospective study derived data from 100% national Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data files from July 1, 2013, through June 1, 2015.

Participants:

Criteria from the Home Health Claims-Based Rehospitalization Measure and the Potentially Preventable 30-Day Post Discharge Readmission Measure for the Home Health Quality Reporting Program were used to identify a cohort of 118,171 Medicare beneficiaries.

Main Outcome Measure:

The 30-day PPR rates with associated 95% CIs were calculated for each patient characteristic. Multilevel logistic regression was used to study the relationship between mobility, self-care, caregiver support, and cognition domains and 30-day PPR during home health, adjusting for patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

Results:

The overall rate of 30-day PPR was 7.6%. In the fully adjusted models, patients who were most dependent in mobility (odds ratio [OR], 1.59; 95% CI, 1.47–1.71) and self-care (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.61–1.87) had higher odds for 30-day PPR. Patients with unmet caregiving needs had 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05–1.17) higher odds for 30-day PPR than patients whose caregiving needs were met. Patients with cognitive impairment had 1.23 (95% CI, 1.16–1.30) higher odds of readmission than those with minimal to no cognitive impairment.

Conclusions:

Decreased independence in mobility and self-care tasks, unmet caregiver needs, and impaired cognitive processing at admission to home health are associated with risk of 30-day PPR during home health for individuals with dementia. Our findings indicate that deficits in mobility and self-care tasks have the greatest effect on the risk for PPR.

Keywords: Caregivers, Dementia, Health status, Home care agencies, Patient readmission, Rehabilitation

Nearly half of Medicare beneficiaries in 2017 were discharged from hospitalizations to postacute care.1 Many patients prefer to return home after hospitalization.2,3 Home health is an attractive postacute care option because nursing and rehabilitation services are provided in the home.4 This is especially true for the 30% of home health patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD), who function best in familiar settings.5,6

The use of home health and associated health care costs have risen steadily since the 1990s, increasing the demand for agencies to provide high-quality care.7,8 Home Health Compare reports the performance of home health agencies on 13 quality measures.9 Quality measures are calculated using data from Medicare claims files and the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), which is the patient assessment tool used in home health at the start of care. One measure tracks readmissions during the first 31 days of a home health episode.

In 2016, 14.0% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted to the hospital during the first 30-days of home health.10 Efforts to reduce readmissions rely on prediction models targeting medical diagnoses and focusing on demographics and treatment needs as primary risk factors.11–14 Recent studies have indicated that inclusion of function and cognition may improve the performance of the prediction models and have been endorsed by the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act as priority quality metrics across postacute settings.11,15,16

Less research has investigated the effect caregiver availability has on home health patients’ risk for readmission. A study of over 7000 home health patients who had at least 1 readmission over a 1-year period found that those patients living alone were 1.2 times more likely to experience 3 or more unplanned readmissions than patients who did not live alone.17 An analysis of 552 home health patients with heart failure revealed that living with another person was associated with lower readmission rates.18

The presence of a caregiver who can assist with daily activities is an important factor in determining if home health is appropriate.19 For individuals with ADRD, caregiver support is an essential component of remaining in the community. Home health patients with ADRD who have unmet caregiver needs may be at an increased risk for hospital readmission. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated the relationship between caregiver support and 30-day readmissions from home health for patients with ADRD.

Individuals with ADRD often receive home health after being discharged from the hospital.5,20,21 Older adults with ADRD are at an increased risk to be readmitted,22–25 but relatively little research has investigated the readmission rates for individuals with ADRD who were discharged to home health. The purpose of this study is to determine the relationship between patient status (function, cognition, caregiver availability) at admission to home health and the risk for potentially preventable readmissions (PPRs) during home health among individuals with ADRD.

Methods

Data sources

Data were derived from the following 100% national Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) administrative and clinical assessment data files from July 1, 2013, through June 1, 2015: Home Health Base file, OASIS, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review, and Beneficiary Summary files. The Home Health Base file was used to identify the cohort and to confirm start and end dates of care. Data from the OASIS file were used to create the mobility, self-care, caregiver support, and cognition domains. Validity varies item by item on the OASIS, with functional items having the strongest validity and more moderate validity reported for cognition and other domains.26 The Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file was used to identify index hospitalizations, dementia codes, and readmissions. The Beneficiary Summary file was used to verify Medicare Fee for Service enrollment and to obtain sociodemographic information. This study was approved by our university’s institutional review board. A Data Use Agreement was reviewed and approved by CMS.

Patient cohort

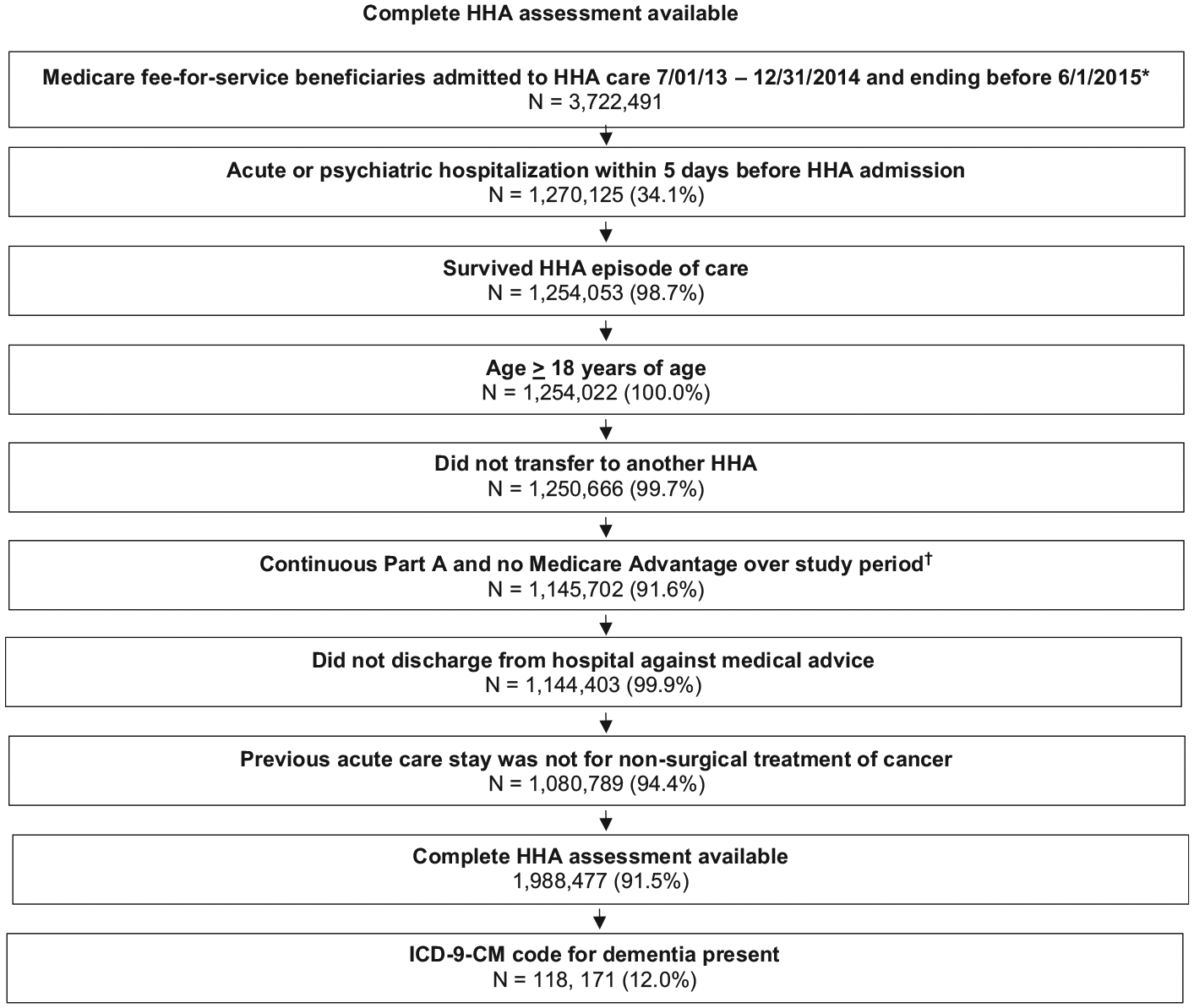

Criteria from the following measure specification models were used to identify our cohort from 4,258,284 Medicare beneficiaries admitted to home health between July 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014 whose episodes ended before June 1, 2015 (fig 1): (1) Home Health Claims-Based Rehospitalization Measure and (2) the Potentially Preventable 30-day Post Discharge Readmission Measure for the Home Health Quality Reporting Program.10,27 We excluded individuals for the following reasons: (1) admitted to home more than 5 days after discharge from an acute or psychiatric hospitalization; (2) noncontinuous Medicare Fee for Service coverage for 12 months prior to the index hospitalization and 32 days after the hospital discharge; (3) home health provider was outside of the United States, Puerto Rico, or a United States territory; (4) transferred between home health agencies; (5) younger than 18 years; (6) no dementia diagnosis; (7) missing administrative data necessary to identify a dementia diagnosis; (8) discharged from the acute care hospitalization against medical advice; (9) died during the home health episode; (9) index hospitalization was for nonsurgical treatment of cancer were excluded; or (10) missing items of interest on the OASIS.

Fig 1.

Cohort selection. Flow chart depicting cohort selection at each step as exclusion criteria were applied. NOTE. Percentages represent percent remaining from previous step. Author’s cohort selection derived from the 100% national Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data files during the period of July 1, 2013, through June 1, 2015: Home Health Base file, OASIS, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review, and Beneficiary Summary files. Abbreviations: HHA, home health agency; US, United States. *1st admission was selected if patient had more than 1 between 7/1/2013–6/1/2015. †“Study period” refers to the 1 year prior to the index hospitalization through the 32 days postdischarge for each index hospitalization.

Dementia diagnosis

Beneficiaries with dementia were identified using 23 International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes included in the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse algorithm for Alzheimer disease, related disorders, or senile dementia (supplemental appendix S1, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/).28 Beneficiaries with 1 or more ICD-9 codes for dementia in Medicare Part A, home health, skilled nursing, or inpatient rehabilitation claims in the year prior to hospitalization were classified as having dementia.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was the occurrence of a PPR within 30 days of starting home health. The 30-day observation window was determined by adding 30 days to the “from” date in the index home health claim. We used the criteria and ICD-9 codes described in the 30-day PPR Post Discharge Readmission Measure for the Home Health Quality Reporting Program, adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, to identify PPRs that occurred within 30 days of starting home health (supplemental appendix S2, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/).10

Primary predictors

We used 3 items for mobility: (1) transferring to/from a toilet, (2) transfer to/from bed to chair, and (3) ambulation (supplemental appendix S3, available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/). Transferring to/from a toilet is rated on a scale of 1 (independent) to 5 (totally dependent). Transferring to/from bed to chair is rated on a scale of 1 (independent) to 6 (cannot position self in bed). Ambulation is rated on a scale of 1 (independent) to 7 (bedfast and cannot be in a chair).

The 7 OASIS items within the self-care domain addressed grooming, dressing upper and lower body, bathing, hygiene, eating, and meal preparation. The items for grooming, dressing upper and lower body, and toileting hygiene are assessed according to 4 levels that rate a patient from independent to entirely dependent on another person. Bathing is rated on a scale of 1 (independent) to 7 (cannot use a shower or tub and is totally dependent on another person). Eating is rated on a scale of 1 (independent) to 6 (cannot take nutrients orally or by tube feeding). The ability to plan and prepare light meals is rated as independent; cannot regularly prepare meals because of physical, cognitive, or mental limitations; and cannot prepare any meals or reheat delivered meals.

We used individual items to calculate summary scores of mobility and self-care. The different number of response categories means that items will have varying weights in a summary variable that is calculated as a total score. Thus, we rescaled the items in the mobility and self-care domains to range from 0 (independent) to 100 (dependent). As has been done previously (see supplemental appendix S2), we divided each item by the maximum possible score for that item and then multiplied by 100. A summary score was calculated for each domain by averaging the rescaled scores for the mobility and self-care domains. Finally, the average mobility and self-care domain scores were categorized into quartiles.

Measures of cognitive function

The 4 OASIS items that assess cognitive functioning included cognitive functioning, memory deficit, impaired decision making, and speech and oral expression of language (see supplemental appendix S3). The cognitive functioning item reflects the patient’s alertness, orientation, comprehension, concentration, and immediate memory on the day of the assessment (see supplemental appendix S1). A patient is rated on a scale of 0 (alert and oriented, able to focus and shift attention, comprehends and recalls independently) to 4 (totally dependent because of constant disorientation, coma, persistent vegetative state, or delirium). The items for memory deficits and impaired decision making are rated as either absent (0 points) or present (1 point). Speech and verbal expression is rated on a scale of 0 (expresses complex ideas with no impairment) to 5 (cannot speak or nonresponsive).

We did not standardize the cognitive variables because the memory and impaired decision-making variables are dichotomous. The point values assigned to each cognitive variable were summed, and patients were dichotomized into those who had minimal to no cognitive deficits (0–5) and those who demonstrated deficits across all 4 OASIS items (6–11). We chose a cutoff score of 5 points because the 30-day PPR rate was similar for patients who scored between 0 and 5 points.

Measures of caregiver support

The OASIS includes an item that describes the caregiver supports for activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, medication administration, management of medical procedures and/or treatments, equipment management, supervision and/or safety, and advocacy and/or facilitation. Each type of assistance was scored on a 6-category scale: no assistance needed, caregiver currently provides assistance, caregiver needs training to provide assistance, caregiver not likely to provide assistance, unclear if caregiver will provide assistance, and assistance needed but caregiver not available. The 6-category scale was rescaled as a 4-point scale: (1) no assistance needed; (2) caregiver currently provides assistance; (3) caregiver needs training; and (4) a final grouping of caregiver unlikely to provide assistance, unknown if caregiver will provide assistance, or caregiver not available. All items were summed to create a total raw assistance score (0–28) for each patient. A score of 12 or less is consistent with scoring at either (1) no assistance needed or (2) caregiver currently provides assistance for each of the seven types of assistance. Therefore, the caregiver support domain was dichotomized into “Caregiver Needs Met” (raw score ≤12) and “Unmet Caregiver Needs” (raw score≥13).

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race and/or ethnicity, Medicare original entitlement, and dual eligibility status. Healthcare utilization characteristics included receipt of dialysis during hospitalization, length of index hospitalization, days in the intensive care unit and/or critical care unit, and the number of hospitalizations over the previous year.

Data analysis

For each patient characteristic, we calculated 30-day PPR rates, with associated 95% CIs. We used multilevel logistic regression to study the relationship between mobility, self-care, caregiver support, and cognition domains and 30-day PPR during home health adjusting for patient demographics and clinical characteristics. Multilevel logistic regression was used to account for the clustering of patients within home health agencies. We examined the association between each domain and 30-day PPR with and without the other domains as additional risk adjustors and assessing for multicollinearity.

Results

The final cohort consisted of 118,171 individuals with ADRD. Within the sample, 65% were 81 years or older, 61% were female, and 80% were white (table 1). The overall 30-day PPR rate was 7.6%. Readmission rates were significantly higher for dual eligible patients (8.8%) compared with nondual eligible patients (7.2%) and increased with greater acute care length of stay and number of days spent in the intensive care unit. The largest difference in 30-day PPR rates were according to the number of acute hospital stays in the prior year with 4 or more stays having a 30-day PPR rate of 25.2% compared with 2.5% for patients with no other acute stays the previous year. Observed 30-day PPR rates increased as the level of independence decreased across all 4 domains.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics and observed rates of 30-day PPR during home health

| Variables | Overall Sample, n (%) | Observed Rate of RA % (95% CI) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 118,171 | 7.6 (7.4–7.7) | |

| Age (y) | |||

| 18–65 | 3157 (2.6) | 8.0 (7.1–9.0) | |

| 66–70 | 6055 (5.1) | 7.3 (6.7–8.0) | |

| 71–75 | 11,519 (9.8) | 7.5 (7.0–8.0) | |

| 76–80 | 19,927 (16.8) | 7.4 (7.1–7.8) | |

| 81+ | 77,513 (65.6) | 7.6 (7.4–7.8) | |

| Sex | ∥ | ||

| Male | 45,429 (38.4) | 7.8 (7.6–8.1) | |

| Female | 72,742 (61.6) | 7.4 (7.2–7.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ∥ | ||

| White | 94,363 (80.0) | 7.4 (7.2–7.5) | |

| Black | 13,246 (11.2) | 8.5 (8.0–8.9) | |

| Hispanic | 6876 (5.8) | 8.5 (7.8–9.2) | |

| Other | 3686 (3.1) | 7.8 (7.0–8.7) | |

| Medicare original entitlement* | ∥ | ||

| Age | 102,696 (87.0) | 7.4 (7.2–7.5) | |

| Disability | 14,977 (12.7) | 8.6 (8.2–9.1) | |

| ESRD | 203 (0.2) | 9.7 (6.2–14.5) | |

| ESRD and disability | 295 (0.2) | 15.6 (11.8–20.1) | |

| Dual eligibility† | ∥ | ||

| No | 93,329 (79.1) | 7.2 (7.1–7.4) | |

| Yes | 24,842 (21.0) | 8.8 (8.5–9.2) | |

| Dialysis during index hospitalization | ∥ | ||

| No | 118,125 (99.9) | 7.6 (7.4–7.7) | |

| Yes | 46 (0.1) | 9.6 (1.9–19.9) | |

| Index hospitalization length of stay (d) | ∥ | ||

| 1–2 | 29,003 (24.6) | 5.9 (5.6–6.1) | |

| 3 | 23,115 (19.6) | 6.4 (6.1–6.7) | |

| 4 | 17,806 (15.1) | 7.5 (7.2–7.9) | |

| 5 | 12,637 (10.7) | 8.2 (7.7–8.7) | |

| 6–7 | 15,557 (13.1) | 8.8 (8.4–9.3) | |

| 8+ | 20,053 (17.0) | 10.0 (9.6–10.4) | |

| Index hospitalization ICU/CCU utilization (d) | ∥ | ||

| 0 | 76,990 (65.2) | 7.1 (6.9–7.3) | |

| 1–2 | 15,781 (13.4) | 7.0 (6.6–7.4) | |

| 3–4 | 13,208 (11.2) | 7.8 (7.3–8.3) | |

| 5+ | 12,192 (10.3) | 10.9 (10.3–11.4) | |

| Acute stays over prior year (count) | ∥ | ||

| 0 | 63,969 (54.1) | 2.5 (2.3–2.6) | |

| 1 | 29,816 (25.2) | 9.8 (9.5–10.2) | |

| 2 | 13,079 (11.1) | 14.9 (14.3–15.5) | |

| 3 | 5794 (5.0) | 19.1 (18.1–20.1) | |

| 4+ | 5513 (4.7) | 25.2 (24.1–26.4) | |

| Mobility scores‡ | ∥ | ||

| Quartile 1 (raw score 0–25.6) | 24,837 (21.0) | 5.9 (5.6–6.2) | |

| Quartile 2 (raw score 26.1–31.7) | 40,590 (34.3) | 6.6 (6.4–6.9) | |

| Quartile 3 (raw score 32.8–45.6) | 23,075 (19.5) | 7.4 (7.1–7.7) | |

| Quartile 4 (raw score 46.7–100) | 29,669 (25.0) | 10.4 (10.0–10.7) | |

| Self-care scores‡ | ∥ | ||

| Quartile1 (raw score 0–41.0) | 28,801(24.4) | 5.8 (5.5–6.1) | |

| Quartile 2 (raw score 41.1–55.7) | 30,221 (25.6) | 6.8 (6.5–7.1) | |

| Quartile 3 (raw score 56.2–67.6) | 29,543 (25.0) | 7.3 (7.0–7.6) | |

| Quartile 4 (raw score 68.1–100) | 29,696 (25.1) | 10.4 (10.1–10.8) | |

| Cognitive status§ | ∥ | ||

| Intact (score≤5) | 17,126 (14.5) | 7.1 (6.7–7.5) | |

| Impaired (score≥5) | 101,045 (85.5) | 7.6 (7.5–7.8) | |

| Caregiver support§ | ∥ | ||

| Caregiver needs met (score≤12) | 40,762 (34.5) | 6.4 (6.2–6.6) | |

| Unmet caregiver needs (score≥12) | 77,409 (65.5) | 8.2 (8.0–8.4) |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ICU/CCU, intensive care unit/critical care unit; RA, readmission.

Original reason for Medicare enrollment.

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Mobility and self-care domains created using items from the Home Health OASIS.

Cognition and Social support domains were created using items from the OASIS.

Significant difference in PPR at level of .01.

Across all 4 domains, status at admission to home health was associated with 30-day PPR (table 2). After adjusting for patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the odds ratio (OR) for the most dependent quartile vs the most independent quartile was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.56–1.80) for mobility, and 1.78 (95% CI, 1.66–1.91) for self-care. Adjusting for cognition and caregiver support had minimal effect on the relationship between mobility or self-care and PPR (see table 2). Mobility and self-care scores were never included in the same model because of multi-collinearity between the 2 domains.

Table 2.

Odds ratios from adjusted multilevel logistic regression models estimating the association between functional and social support scores at admission with potentially preventable 30-day readmissions following home health care

| Domains | Odds Ratio* (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility† | Not Adjusted for Other Domains | Adjusted for Cognition and Assistance | ||

| Quartile 1 (most independent) (raw score 0–25.6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Quartile 2 (raw score 26.1–31.7) | 1.13 (10.5–1.21)¶ | 1.10 (1.03–1.18)¶ | ||

| Quartile 3 (raw score 32.8–45.6) | 1.25 (1.16–1.35)¶ | 1.21 (1.12–1.31)¶ | ||

| Quartile 4 (most dependent) (raw score 46.7–100) | 1.68 (1.56–1.80)¶ | 1.59 (1.47–1.71)¶ | ||

| Self-care† | Not Adjusted for Other Domains | Adjusted for Cognition and Assistance | ||

| Quartile 1 (most independent) (raw score 0–41) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Quartile 2 (raw score 41.1–55.7) | 1.16 (1.09–1.25)¶ | 1.14 (1.07–1.23)¶ | ||

| Quartile 3 (raw score 56.2–67.6) | 1.26 (1.18–1.35)¶ | 1.24 (1.15–1.33)¶ | ||

| Quartile 4 (most dependent) (raw score 68.1–100) | 1.78 (1.66–1.91)¶ | 1.73 (1.61–1.87)¶ | ||

| Cognitive status‡ | Not Adjusted for Other Domains | Adjusted for Assistance | Adjusted for Assistance and Self-care | Adjusted for Assistance and Mobility |

| Intact (score<5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Impaired (score>5) | 1.23 (1.16–1.30)¶ | 1.21 (1.13–1.29)¶ | 1.07 (1.01–1.14)∥ | 1.00 (0.938–1.06) |

| Caregiver support§ | Not Adjusted for Other Domains | Adjusted for Cognition | Adjusted for Cognition and Self-care | Adjusted for Cognition and Mobility |

| Caregiver needs met (score<12) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unmet caregiver needs (score>12) | 1.2 (1.14–1.26)¶ | 1.17 (1.11–1.23)¶ | 1.11 (1.05–1.16)¶ | 1.10 (1.05–1.17)¶ |

Odds ratios from multilevel models adjusted for patients’ age; sex; race/ethnicity; dual eligibility; Medicare original reason for entitlement; number of hospitalizations over the prior year; comorbidities (hierarchical condition categories); and index hospitalization diagnostic category, primary procedure (if applicable), length of stay, receipt of dialysis, and intensive or coronary care unit utilization.

Mobility and self-care domains created using items from Home Health OASIS. The mobility domain included 3 items related to transfers and ambulation/locomotion. The self-care domain included 7 items related to feeding, preparing light meals, grooming, dressing, bathing, and toilet hygiene.

Cognitive categories created using 4 OASIS items.

Assistance domain created using 1 item from the OASIS.

Significant difference from the reference value at the level of .05.

Significant difference from the reference value at the level of .01.

After adjusting for patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the OR for Unmet Caregiver Needs vs Met Care-giver Needs was 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26). There was minimal change in the OR when adjusting for cognition 1.17 (95% CI, 1.11–1.23). The odds of PPR decreased for Unmet Caregiver Needs when adjusting for mobility, with OR of 1.10 (95% CI, 1.05–1.17) and self-care, with OR of 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05–1.17). After adjusting for patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the OR for PRR for low cognitive impairment vs significant cognitive impairment was 1.23 (95% CI, 1.16–1.30). There was minimal change in the OR when adjusting for caregiver support at 1.21 (95% CI, 1.13–1.29). The odds of PPR decreased for significant cognitive impairment when adjusting for mobility, with OR of 1.07 (95% CI, 1.01–1.14) and was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for self-care, with OR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.938–1.06).

The 5 most common conditions resulting in PPR were congestive heart failure (19%), septicemia (17%), renal failure (10%), urinary tract infection (11%), and bacterial pneumonia (9%) and were similar across quartiles of all 4 domains except for the most dependent quartiles of mobility and self-care. In the most dependent quartile for mobility and self-care, the first and second most common conditions resulting in PPR were septicemia and urinary tract infections followed by congestive heart failure, renal failure, and bacterial pneumonia.

Discussion

The overall rate of PPR was 7.6%, representing 8980 individuals with ADRD. Hospitalizations of individuals with ADRD are associated with heightened risks of negative outcomes and cost 3 times greater than individuals without ADRD.29–31 Even at the relatively low readmission rate of 7.6%, these PPRs have sub stantial financial implications for the health care system.

Functional status and availability of caregiver support at admission to home health were associated with 30-day PPR during home health for individuals with ADRD. Individuals who were the most dependent for mobility and self-care had the greatest odds of readmission. These odds did not significantly change when controlling for cognition or caregiver support. This suggests that regardless of cognitive impairment or unmet caregiver needs, it is the patient’s ability to be mobile and complete self-care tasks that is most associated with risk of PPR. Prior research has reported similar associations between functional independence and PPR after discharge from home health.15,32,33 Level of dependence in mobility and self-care tasks are actionable patient characteristics targeted by clinicians during home health. Identifying individuals with ADRD who are at high risk of PPR because of mobility and self-care deficits facilitates implementation of interventions to decrease readmissions. Further research is needed to identify interventions that can positively affect the odds of PPR for individuals with ADRD.34,35

Odds of PPR were higher for individuals with ADRD who had significant cognitive deficits than those with minimal to no cognitive deficits. However, significant cognitive deficit was not associated with increased odds of PPR after controlling for mobility. Progression of ADRD includes declines in both cognition and functional abilities.36,37 Our findings suggest that it is the functional decline associated with ADRD that may have the most significant effect on PPR risk.

Caregiver support is essential in the middle and late stages of ADRD.36–38 Unmet caregiver needs are assumed to lead to negative health outcomes for individuals with ADRD. In our study, individuals with ADRD who had unmet caregiver needs did have increased odds of PPR, but the magnitude of risk was reduced after adjusting for mobility and self-care. This finding is important because home health agencies may not be able to change whether a patient has available caregiver support but do have the ability to address mobility and self-care deficits.

The 5 most common PPR conditions reflect inadequate management of chronic conditions and secondary infections. Congestive heart failure was the most common reason for PPR across all 4 domains in all quartiles with the exception of the most dependent quartile of mobility and self-care.39 This is consistent with a study of 1,510,297 home health patients that found congestive heart failure was the most common PPR after discharge from home health.33 Interventions to reduce PPRs related to congestive heart failure have been proven effective in other patient populations,40–42 but further research is needed to determine if these strategies are also effective for individuals with ADRD. In the most dependent quartiles of mobility and self-care, septicemia, a secondary infection, was the most common reason for readmission. Decreased independence with mobility and self-care tasks in the later stages of ADRD have been associated with increased risk for secondary infections.43–46

Study limitations

Our study has limitations. First, the OASIS does not include an objective measure of cognitive functioning. Next, our definition of ADRD was based only on an ICD-9 diagnosis that has been shown to have poor sensitivity for detecting ADRD.47 A diagnosis of dementia usually occurs after the onset of symptoms. However, in our study, there were individuals who were diagnosed as having dementia scored as having minimal to no cognitive deficits. By dichotomizing cognitive impairment, we were not able to distinguish across stages of dementia. The reliance on ICD-9 in the PPR measure adopted by CMS is consistent with the methodology we used, but these codes may not be universally agreed upon. Finally, we used admissions data to determine the availability of caregiver support and cannot determine if it changed after the point of admission, which may affect the risk for readmission.

Conclusions

Decreased independence in mobility and self-care tasks, a lack of caregiver support when needed, and impaired cognitive processing at admission to home health are associated with risk of 30-day PPR during home health for individuals with ADRD. Despite cognitive impairment being a hallmark of ADRD, our findings indicate that it is deficits in mobility and self-care tasks that have the greatest effect on the risk for PPR. Further research is needed to determine if intervention strategies targeting mobility and self-care deficits can change the risk of PPR for individuals with ADRD. Next steps will be to consider the effect ADRD may have on other long-term outcomes, such as successful discharge to community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. R01HD069443, P2CHD065702, K01AG058789, U54GM104941), National Institute of Aging (grant no. K01AG058789), and the Foundation for Physical Therapy’s Center of Excellence in Physical Therapy Health Services and Health Policy Research and Training Grant.

List of abbreviations:

- ADRD

Alzheimer disease and related dementias

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision

- OASIS

Outcome and Assessment Information Set

- OR

odds ratio

- PPR

potentially preventable readmissions

Footnotes

Presented to the Gerontological Society of America, November 13–17, 2019, Austin, TX, and the American Congress of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, November 3–8, 2019, Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A databook: healthcare spending and the Medicare program. 2019. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun19_databook_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsnZ0. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- 2.Gregory P, Edwards L, Faurot K, Williams SW, Felix AC. Patient preferences for stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil 2010;17:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sefcik JS, Ritter AZ, Flores EJ, et al. Why older adults may decline offers of post-acute care services: a qualitative descriptive study. Geriatr Nurs 2017;38:238–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home health providers. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/HHAs.html. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- 5.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital Health Stat 2016;3:1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Son GR, Therrien B, Whall A. Implicit memory and familiarity among elders with dementia. J Nurs Scholarsh 2002;34:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:295–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Home health care expenditures in the United States from 1960 to 2016. In: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. Accessed August 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home health compare. Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/HHCompare/Home.asp. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- 10.Acumen LLC. Home health claims-based rehospitalization measures technical report. 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Home-Health-Quality-Measures. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- 11.Shih SL, Gerrard P, Goldstein R, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities in predicting acute care readmissions in medically complex patients. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1688–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma C, Shang J, Miner S, Lennox L, Squires A. The prevalence, reasons, and risk factors for hospital readmissions among home health care patients: a systematic review. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2018;30:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohman MC, Scherer EA, Whiteman KL, Greenberg RL, Bruce ML. Factors associated with accelerated hospitalization and rehospitalization among Medicare home health patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:1280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bick I, Dowding D. Hospitalization risk factors of older cohorts of home health care patients: a systematic review. Home Health Care Serv Q 2019;38:111–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Middleton A, Graham JE, Lin YL, et al. Motor and cognitive functional status are associated with 30-day unplanned rehospitalization following post-acute care in Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. IMPACT Act of 2014 data standardization and cross setting measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Post-Acute-Care-Quality-Initiatives/IMPACT-Act-of-2014-and-Cross-Setting-Measures.html. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- 17.Rosati RJ, Huang L, Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH. Risk factors for repeated hospitalizations among home healthcare recipients. J Healthc Qual 2003;25:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang Y, McHugh MD, Chittams J, Bowles KH. Utilizing home healthcare electronic health records for telehomecare patients with heart failure: a decision tree approach to detect associations with rehospitalizations. Comput Inform Nurs 2016;34:175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss ME, Bobay KL, Bahr SJ, Costa L, Hughes RG, Holland DE. A model for hospital discharge preparation: from case management to care transition. J Nurs Adm 2015;45:606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callahan CM, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Medicare utilization and expenditures before and after the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:180. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin PJ, Zhong Y, Fillit HM, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions and unplanned readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2017;13:1174–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin PJ, Fillit HM, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daiello LA, Gardner R, Epstein-Lubow G, Butterfield K, Gravenstein S. Association of dementia with early rehospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014;59:162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickens S, Naik AD, Catic A, Kunik ME. Dementia and hospital readmission rates: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2017;7:346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor M, Davitt J. Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS): a review of validity and reliability. Home Health Care Serv Q 2012;31:267–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abt Associates. Measure specifications for measures in the CY 2017 HH QRP final rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Downloads/MeasureSpecificationsForCY17-HH-QRP-FR.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- 28.Taylor D, Fillenbaum G, Ezell M. The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55: 929–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arling G, Tu W, Stump TE, Rosenman MB, Counsell SR, Callahan CM. Impact of dementia on payments for long-term and acute care in an elderly cohort. Med Care 2013;51:575–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:332–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1326–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Middleton A, Graham JE, Ottenbacher KJ. Functional status is associated with 30-day potentially preventable hospital readmissions after inpatient rehabilitation among aged Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2018;99:1067–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middleton A, Downer B, Haas A, Knox S, Ottenbacher KJ. Functional status is associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions following home health care. Med Care 2019;57:145–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Middleton A, Downer B, Haas A, Lin Y-L, Graham JE, Ottenbacher KJ. Functional status is associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions following skilled nursing facility discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Middleton A, Graham JE, Deutsch A, Ottenbacher KJ. Potentially preventable within-stay readmissions among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving inpatient rehabilitation. PM R 2017;9:1095–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2019;15:321–87. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auer S, Reisberg B. The GDS/FAST staging system. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9(Suppl. 1):167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin JM, Meis LA, Greer N, et al. Effectiveness of caregiver interventions on patient outcomes in adults with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2015;1 2333721415595789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Availabe at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Feefor-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed January 16, 2016.

- 40.Ong MK, Romano PS, Edgington S, et al. Effectiveness of remote patient monitoring after discharge of hospitalized patients with heart failure: the Better Effectiveness After Transition — Heart Failure (BEAT-HF) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med 2016; 176:310–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackevicius CA, de Leon NK, Lu L, Chang DS, Warner AL, Mody FV. Impact of a multidisciplinary heart failure post-hospitalization program on heart failure readmission rates. Ann Pharmacother 2015;49: 1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cene CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:774–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowe TA, Juthani-Mehta M. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2014;28:75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunnström HR, Englund EM. Cause of death in patients with dementia disorders. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudolph JL, Zanin NM, Jones RN, et al. Hospitalization in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1542–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, et al. Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:1038–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.