Abstract

PURPOSE

Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) is common during adjuvant chemotherapy and may persist. TAILORx provided a novel opportunity to prospectively assess patient-reported cognitive impairment among women with early breast cancer who were randomly assigned to chemoendocrine therapy (CT+E) versus endocrine therapy alone (E), allowing us to quantify the unique contribution of chemotherapy to CRCI.

METHODS

Women with a 21-gene recurrence score of 11 to 25 enrolled in TAILORX were randomly assigned to CT+E or E. Cognitive impairment was assessed among a subgroup of 552 evaluable women using the 37-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog) questionnaire, administered at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months. The FACT-Cog included the 20-item Perceived Cognitive Impairment (PCI) scale, our primary end point. Clinically meaningful changes were defined a priori and linear regression was used to model PCI scores on baseline PCI, treatment, and other factors.

RESULTS

FACT-Cog PCI scores were significantly lower, indicating more impairment, at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months compared with baseline for both groups. The magnitude of PCI change scores was greater for CT+E than E at 3 months, the prespecified primary trial end point, and at 6 months, but not at 12, 24, and 36 months. Tests of an interaction between menopausal status and treatment were nonsignificant.

CONCLUSION

Adjuvant CT+E is associated with significantly greater CRCI compared with E at 3 and 6 months. These differences abated over time, with no significant differences observed at 12 months and beyond. These findings indicate that chemotherapy produces early, but not sustained, cognitive impairment relative to E, providing reassurance to patients and clinicians in whom adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated to reduce recurrence risk.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) refers to changes or impairments in cognitive function associated with a cancer diagnosis and/or its treatment.1,2 CRCI is one of the most feared adverse effects of cancer treatment.2 CRCI has been associated with decreased health-related quality of life (HRQL)3 and impairments in social4 and occupational functioning.5 Estimates of the prevalence of CRCI among patients with breast cancer range widely, from 16% to 75%, depending on criteria used to quantify impairment.6-10 CRCI may persist for months or years after cancer treatment.11,12 CRCI was colloquially termed “chemo-brain” because of the assumed causality of chemotherapy13; however, prospective longitudinal trials have documented CRCI among patients with breast cancer prior to chemotherapy.10,14-16 Growing recognition of the multifactorial, complex nature of CRCI has led to research on the etiology and underlying mechanisms, including the respective contributions of tumor burden and cancer treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy,17 radiation therapy,18 and endocrine therapy.19-21 The interplay between cancer therapy and individual vulnerability to cognitive decline has been increasingly recognized22-25 and has underscored the need to better understand the unique and respective contributions of anticancer therapies.

The Trial Assigning Individualized Treatment Options (TAILORx) enrolled women with hormone receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative, axillary node–negative early breast cancer; women with a midrange 21-gene recurrence score of 11 to 25 were randomly assigned to chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy (CT+E) or endocrine therapy alone (E).26,27 Given the randomized design, TAILORx offered an unparalleled opportunity to quantify the extent to which chemotherapy uniquely contributes to common and multifactorial symptoms, such as cognitive impairment28 and fatigue,29 and exacerbates adverse effects of endocrine therapy.30 Although prior prospective, longitudinal,9,11 and cross-sectional8 trials have documented cognitive impairments associated with chemotherapy, definitive conclusions about causality could not be drawn, due to the lack of random treatment assignment. To date, differences in CRCI associated with various treatment approaches may be attributable to systematic differences in cancer and other medical characteristics used to determine treatment regimens used, because of nonrandomization to treatment. The prospective, randomized design of TAILORx allowed a comparison of CRCI associated with CT+E versus E among women with equivalent clinical characteristics and provided a rare opportunity to evaluate the trajectory of long-term HRQL31,32 associated with adjuvant systemic therapy.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measure subjective experiences from the patient’s perspective, such as symptoms, thus PROs are considered the gold standard for quantifying symptomatic treatment effects.33,34 PROs have been widely used to document patient-reported cognitive impairment among women with breast cancer during and after treatment.8,10,17,35 Improved understanding of the extent to which chemotherapy contributes to CRCI during and after treatment can provide valuable insights with regard to underlying mechanisms and can inform discussions about the trade-off between treatment burden and potential benefit.36 The primary objective of this TAILORx substudy was to compare patient-reported cognitive impairment among women with early breast cancer randomly assigned to CT+E or E.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

TAILORx was coordinated by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00310180).26,27 TAILORx enrolled patients with breast cancer (N = 10,273) from April 2006 through October 2010 and was amended in January 2010 to add a PRO substudy. This amendment was approved by local human investigations committees at participating institutions before the collection of PRO data. Women consecutively enrolled from January 15, 2010 to October 25, 2010 (n = 964) completed PRO measures, including 675 women in the intermediate-risk group randomly assigned to CT+E versus E. All participants provided written informed consent. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

TAILORx enrolled women who were 18 to 75 years old, diagnosed with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative, axillary node–negative breast cancer, and met National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for recommendation of adjuvant chemotherapy based on primary tumor size and grade, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1. Additional details on TAILORx eligibility criteria, randomization, and treatment have been published.26,27

Study Measures: PROs

PROs were completed on paper by study participants. Cognitive function was assessed using the well-validated Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog), version 3,37,38 which includes scales measuring Perceived Cognitive Impairment (PCI; n = 20 items), Perceived Cognitive Abilities (n = 9 items), Comments From Others (n = 4 items), and Impact on Quality of Life (n = 4 items). The FACT-Cog has been used in multisite trials assessing CRCI.11 The FACT-Cog was administered at baseline (trial registration and randomization), 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months. Sites were instructed to submit PRO data at all assessments even if earlier assessments were missing. The FACT-COG PCI scale score was the primary end point. A higher FACT-Cog PCI score indicates less cognitive impairment. HRQL was assessed at baseline, 12 months, and 36 months using the FACT-General (FACT-G), a 27-item measure that assesses physical (n = 7 items), functional (n = 7 items), emotional (n = 6 items), and social/family well-being (n = 7 items).39 For the FACT-G, a higher score indicates better HRQL. Trial participants completed additional PROs to assess secondary end points, namely, fatigue,40-42 endocrine symptoms,43 and fear of recurrence44; results will be reported separately.

Statistical Analysis

The difference in FACT-Cog PCI scores between treatment arms at 3 months, controlling for baseline PCI, was the primary end point. For the purposes of sample-size planning, a PCI change score > 4.5 (0.3 standard deviation [SD], assuming PCI SD = 15) from baseline was defined a priori as clinically meaningful on the basis of a distribution-based method calculated using preexisting data.45 The primary time point for analysis was defined as 3 months because most women who were randomly assigned to chemoendocrine therapy would receive a 12-week regimen and thus would experience maximum treatment adverse effects at 3 months. The PRO substudy was designed to have 90% power for a 4.5-point difference (a 0.3 SD) in the mean change scores from baseline to 3 months between CT+E and E (using a two-sided 5% level test). Planned subset analyses for the pre- and postmenopausal groups specified in the protocol would have 90% power for differences of 7.35 and 5.7 points, corresponding to 0.38 and 0.49 SDs, respectively.

The protocol specified that the primary analysis would compare patients from the randomized groups (ie, CT+E v E) who received their assigned treatment; therefore, a per-protocol analysis was conducted. A sample of 235 women per treatment arm was required to obtain 90% power. To achieve this number, we projected that enrolling 1,000 women would result in 640 women to be randomly assigned to CT+E or E, of whom a total of 470 (n = 235 per arm) would receive treatment per protocol. Separate linear regressions were used to model PCI scores at each time point on baseline PCI, treatment, and other factors, using all cases with data at baseline and at the time point. Means and SDs were computed using all cases available at a time point. Mean change scores from baseline were calculated using all cases with data at baseline and the corresponding time point. For treatment group comparisons, the primary analysis then fit a linear model with treatment group (a binary covariate) and the baseline levels (as a continuous linear covariate) with the test and estimated effect on the basis of the coefficient of the treatment effect. Cases with “baseline” assessments > 7 days after the start of treatment were excluded from these comparisons. The data cutoff for results presented here was February 25, 2016 (the last patient enrolled was 28 months post–36-month assessment). Analyses were conducted with R, version 3.5.1 (https://www.r-project.org/).

RESULTS

Study Population

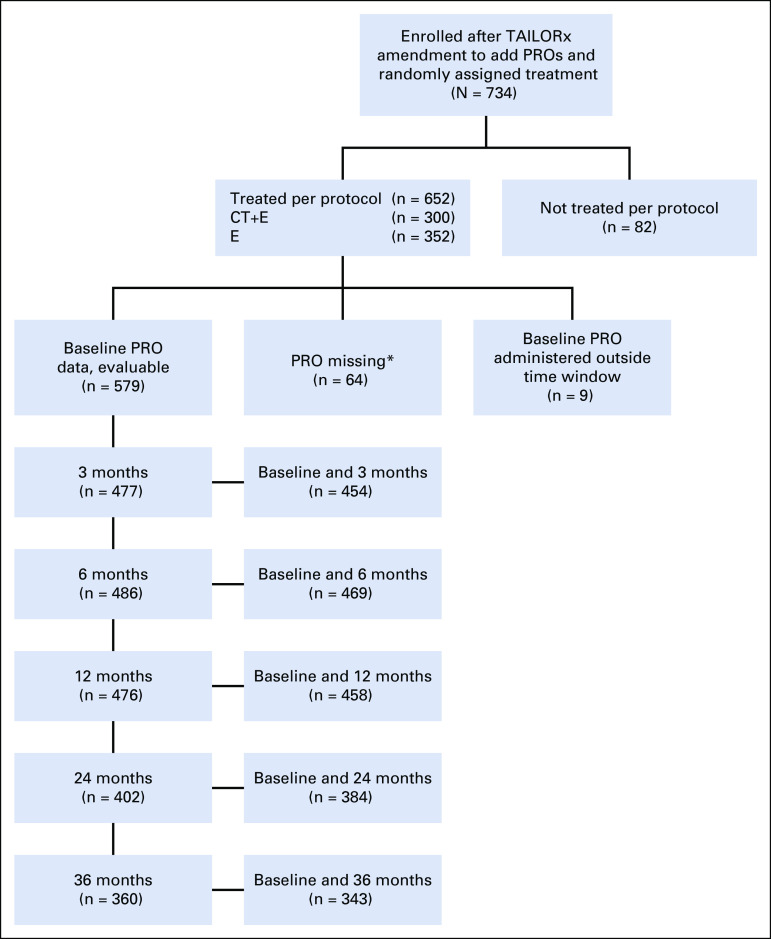

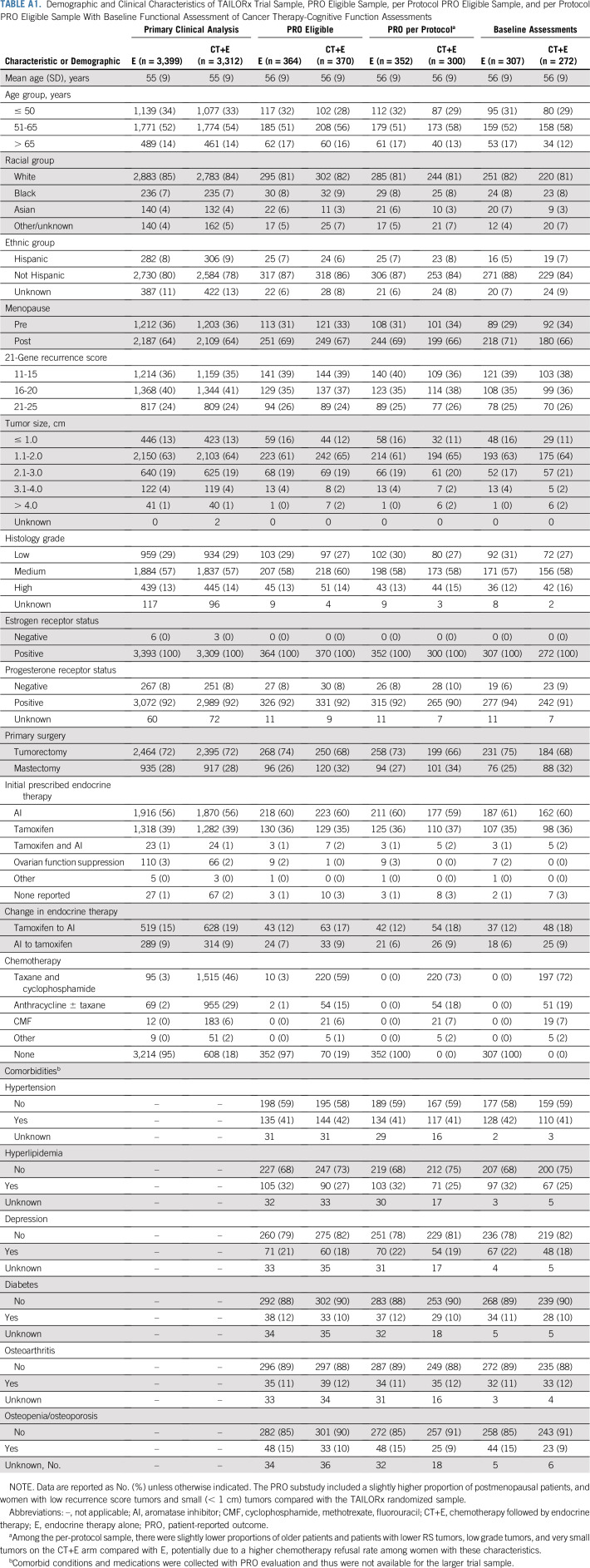

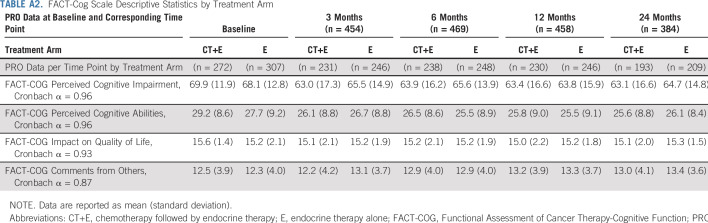

Among 734 women (n = 652 in the per-protocol population) enrolled in TAILORx after PRO substudy approval who had a 21-gene recurrence score of 11 to 25 and were randomly assigned to CT+E versus E, PRO data were submitted for 675 (n = 611 in the per-protocol population). Of these 611, 454 (n = 218 CT+E; n = 236 E [n = 235 per arm had been planned]) had evaluable FACT-Cog PCI data at baseline and 3 months (administered within the required time interval for primary end point; Fig 1 and Fig 2). Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the primary end point population listed in Table 1 with evaluable PRO data at baseline and 3 months (n = 454) were generally comparable to women eligible for PRO participation (n = 734) and the overall TAILORx trial sample26 (Appendix Table A1, online only). Most (58%) received an aromatase inhibitor as initial endocrine therapy and 37% received tamoxifen. Among women randomly assigned to CT+E, the most common chemotherapy regimens were docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide (n = 152; 70%) or anthracycline-based (n = 44; 20%) therapy.

FIG 1.

CONSORT diagram. TAILORx PRO substudy and number of completed FACT-Cog questionnaires submitted, by time point. Sites were instructed to begin administering PROs upon institutional review board approval; some PRO forms were submitted for follow-up assessments from patients with no baseline PRO data. Sites were instructed to administer follow-up PRO assessments even if earlier assessments were missing, thus explaining the higher number of patients with PRO data at 6 months compared to 3 months. (*) Reasons for missing data: patient not given PRO form (n=13), refusal (n=2), other (n=5), unknown (n=5), site did not provide reason (n=39). CT+E, chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy; E, endocrine therapy alone; PRO, patient-reported outcome.

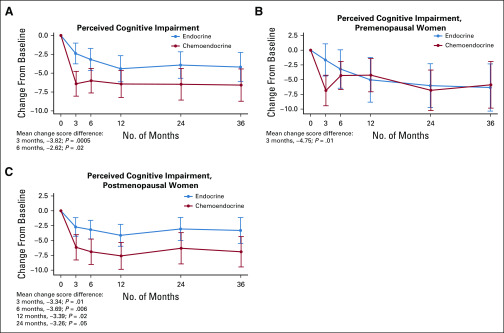

FIG 2.

Trajectory of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Perceived Cognitive Impairment change score from baseline among women treated per protocol for pateint-reported outcome substudy sample. (A) Entire patient-reported outcome substudy sample. (B) Premenopausal sample. (C) Postmenopausal sample.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

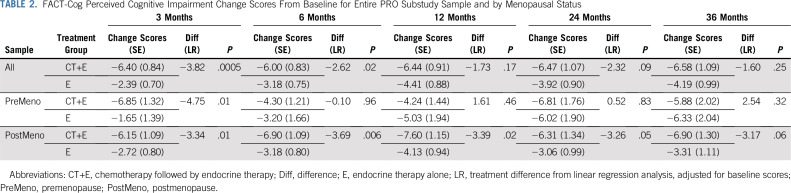

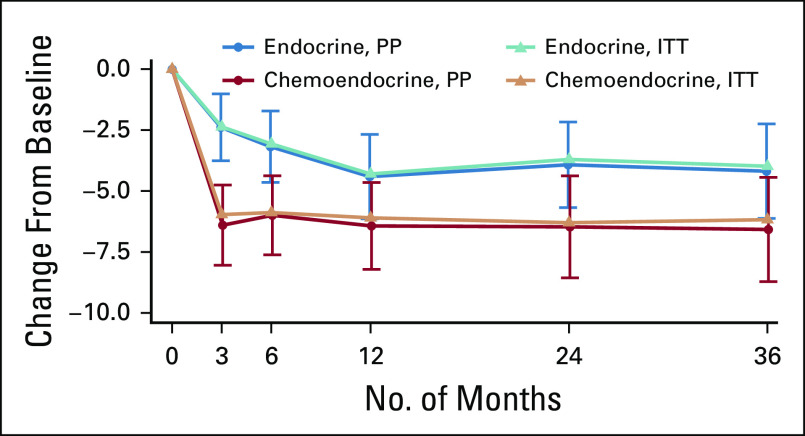

Differences Between Treatment Arms on Perceived Cognitive Impairment

Women randomly assigned to CT+E reported significantly greater cognitive impairment from baseline to 3 months (linear regression difference in mean PCI, −3.82; P < .001) and 6 months (−2.62; P = .02) compared with women randomly assigned to E (Table 2). A change score in a negative direction indicates more impairment. Our a priori defined threshold of 0.3 SD for meaningful change,45 calculated using trial sample distribution information (SD, 12.5), resulted in a clinically meaningful change estimate of 3.75 points. The difference between groups from baseline to 3 months (−3.82), although relatively small, exceeded this threshold. FACT-Cog PCI change scores were comparable between treatment arms at 12, 24, and 36 months. The trajectories of longitudinal FACT-Cog PCI change scores by treatment arm converged over time largely because the E arm reported a gradual increase in cognitive impairment at 12 months that persisted at 24 and 36 months (Fig 2A). Both groups reported significantly more cognitive impairment at all follow-up assessments compared with baseline. A similar pattern of results was observed using an intent-to-treat analysis (Appendix Fig A1).

TABLE 2.

FACT-Cog Perceived Cognitive Impairment Change Scores From Baseline for Entire PRO Substudy Sample and by Menopausal Status

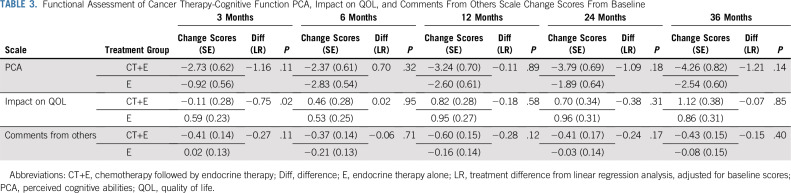

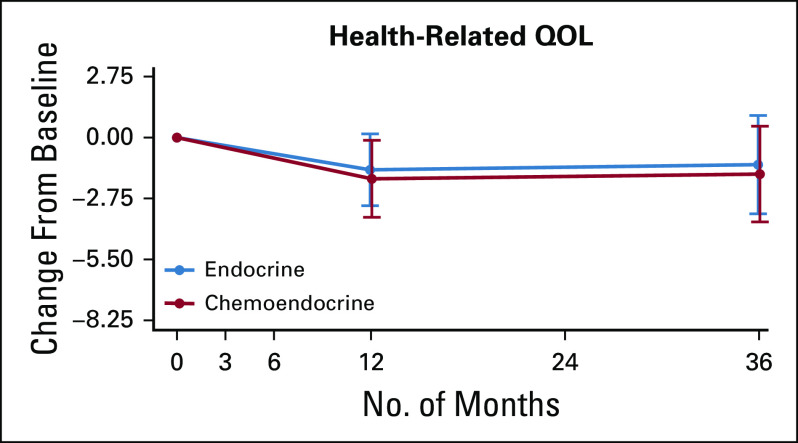

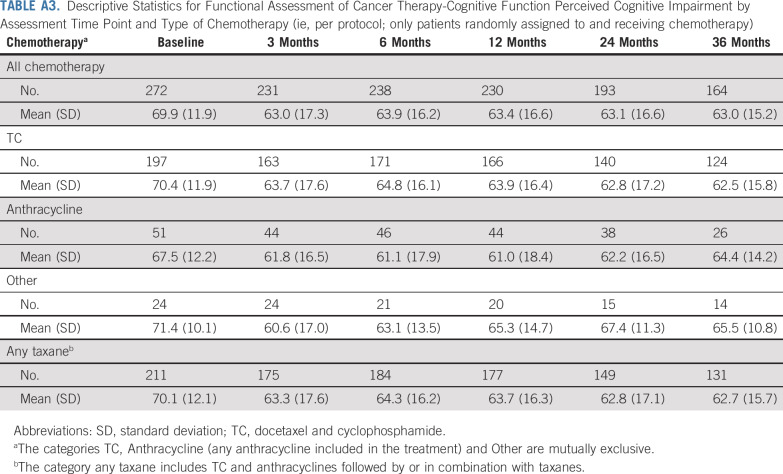

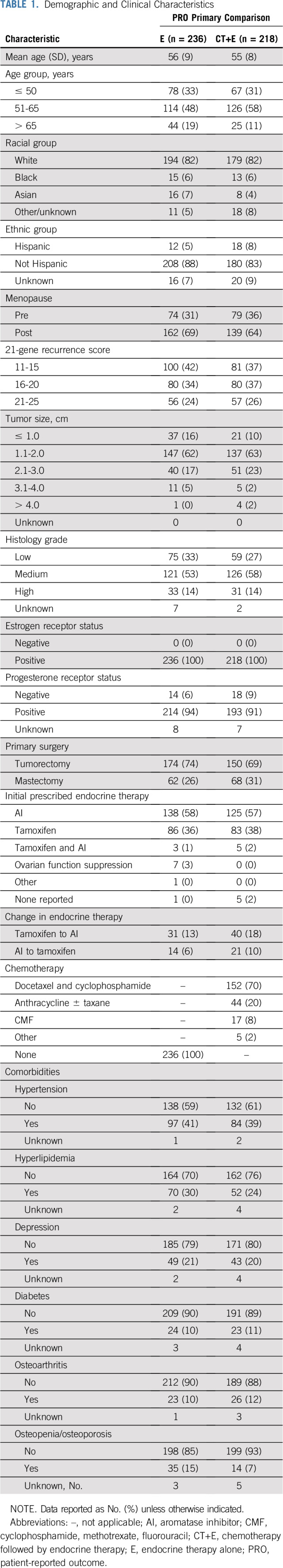

Change scores were comparable between treatment arms at all postbaseline assessments on FACT-Cog scales assessing perceived cognitive abilities, impact on quality of life (QOL), and comments from others (Table 3), with the exception of a greater increase in the impact of cognitive impairment on QOL from baseline to 3 months among women randomly assigned to CT+E versus E. Descriptive statistics for longitudinal FACT-Cog scales by treatment arm are provided in Appendix Table A2 and by chemotherapy regimen (ie, CT+E arm only) in Appendix Table A3). As shown in Figure 3, FACT-G scores were comparable between treatment arms at 12 and 36 months and comparable to baseline levels, indicating equivalent long-term HRQL between arms. Across treatment arms, a multiple linear regression identified increased PCI, fatigue, and endocrine symptoms as significant predictors of HRQL at 12 months (P < .001). Patients with declines in PCI scores ≥ 3.75 points from baseline to 12 months had FACT-G scores 4.0 points lower than those with less than a 3.75-point change (SE, 1.0; P = .00008), after adjusting for the effects of baseline HRQL, fatigue, and endocrine symptoms.

TABLE 3.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function PCA, Impact on QOL, and Comments From Others Scale Change Scores From Baseline

FIG 3.

Trajectory of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General change scores from baseline for women treated per protocol for the entire patient-reported outcome substudy sample. QOL, quality of life.

Differences Between Treatment Arms on PCI by Menopausal Status

PCI change scores were examined by menopausal status. Although the trajectories by treatment appear to be different for pre- versus postmenopausal women (Fig 2B and 2C), tests of an interaction between menopausal status and treatment arm were nonsignificant. Among premenopausal women, mean PCI change scores from baseline to 3 months were significantly greater (−4.75 points; P = .01; Table 2; Fig 2B), reflecting a greater increase in cognitive impairment among women randomly assigned to CT+E compared with E. PCI change scores were comparable between treatment arms at all follow-up times. Among postmenopausal women, those randomly assigned to CT+E reported significantly higher increases in cognitive impairment from baseline to 3, 6, 12, and 24 months compared with women randomly assigned to E (Table 2; Fig 2C). Main effects for age (< 50, 50 to 65, and > 65 years; P = .28) and age-by-treatment interactions (P = .34) were nonsignificant in a linear model examining baseline to 3-month change scores.

Prevalence of Clinically Meaningful PCI by Treatment Arm

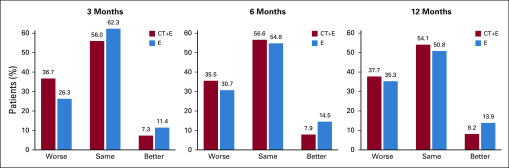

A higher proportion of women randomly assigned to CT+E had a clinically meaningful change in cognitive impairment from baseline to 3 months compared with those in the E group. For this analysis, a more conservative threshold was used to define clinically meaningful change (cutoff, > 0.5 SD) to reduce the proportion classified as worsened due to assessment-level variability and to replicate findings of recently published FACT-Cog results.46,47 Women were categorized as having worsened (PCI score decreased ≥ 6.4 points), stable (± 6.4 points), or improved (PCI score increased ≥ 6.4 points) cognitive impairment on the basis of change from baseline to 3, 6, and 12 months.

Among women randomly assigned to CT+E, 36.7% reported increased cognitive impairment at 3 months compared with 26.3% of women randomly assigned to E (Fig 4). The proportion of women randomly assigned to CT+E categorized with worsening cognitive impairment remained relatively stable over time (35.5% at 6 months; 37.7% at 12 months). At 12 months, the proportion of women randomly assigned to E with worsening cognitive impairment was generally comparable to that in the CT+E group.

FIG 4.

Prevalence of clinically meaningful change in perceived cognitive impairment (FACT-Cog PCI) from baseline to follow-up by treatment arm. The percentage of patients with worsening (Worse), similar (Same), and improving (Better) perceived cognitive impairment, for each treatment arm. A decrease of > 6.4 points from baseline in the PCI is considered worsening, a difference of less than 6.4 in either direction is considered similar, and an increase of > 6.4 is considered improving. The cutoff of 6.4 is 0.5 of the standard deviation of the baseline PCI scores, which has previously been suggested as a threshold to categorize FACT-Cog scores as worse, similar or improved. CT+E, chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy; E, endocrine therapy alone.

DISCUSSION

TAILORx provided a novel opportunity to examine the unique contribution of chemotherapy to CRCI, initially coined “chemo-brain” due to the assumed causal role of chemotherapy. Women randomly assigned to CT+E reported significantly more cognitive impairment acutely during chemotherapy, at 3 and 6 months, compared with women receiving E. At 12, 24, and 36 months, PCI scores were similar between groups. However, this was not due to improvement postchemotherapy in the CT+E group but rather due to declining scores among women receiving E. Among women randomly assigned to CT+E, the majority (70%) received docetaxel and cyclophosphamide, a combination that is generally better tolerated than anthracycline-based chemotherapy and other regimens. Chemotherapy-induced menopause has been suggested as a possible explanation for CRCI.49 However, the nonsignificant interaction between menopausal status and treatment arm in our sample challenges this explanation. Age was not associated with change in cognitive impairment. Women were not differentially affected by treatment based on age group. Our findings suggest an acute effect of chemotherapy on PCI, greater than observed with E, which persists over time and is comparable to E at long-term follow-up. Our findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating chemotherapy is associated with cognitive impairment, though it does not exclusively account for persistent cognitive impairment posttreatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report in which patients were randomly assigned to receive chemotherapy or not. Although we did not observe improvement postchemotherapy, women received E following chemotherapy, which may have contributed to lingering CRCI.

Our finding that women randomly assigned to E reported more cognitive impairment at 12 months and beyond compared with baseline is consistent with emerging evidence demonstrating an association between CRCI and endocrine therapy.50 Postmenopausal women in the ATAC trial demonstrated poorer verbal-memory task performance compared with a noncancer control group.51 Among older women receiving an aromatase inhibitor, cognitive impairment was greater 1 year later compared with pre-aromatase inhibitor therapy.52 A meta-analysis demonstrated an association between verbal learning and memory impairments and endocrine therapy.53 Tamoxifen was associated with lower neuropsychological performance, whereas, in contrast, exemestane was not,21 and anastrozole was comparable to placebo.54 Other trials have reported no additional patient-reported cognitive impairment associated with aromatase inhibitor therapy.25 Collectively, these mixed findings indicate the need for additional research to better understand endocrine therapy and CRCI.

Our conclusions are based on the FACT-Cog PCI scale, our primary end point. We did not observe a similar pattern of results with the additional FACT-Cog scales Perceived Cognitive Abilities and Comments From Others. We have previously recommended separate scoring for FACT-Cog PCI and abilities scales on the basis of our prior research demonstrating these are two separate factors,55 which may explain the different pattern of results between scales. Impact on Quality of Life scale change scores indicate women randomly assigned to CT+E reported a greater impact of cognitive impairment on QOL at 3 months compared with E, and groups were comparable at 6 months and beyond.

CRCI remains a challenging symptom to prevent and treat and is complex, given the myriad factors that contribute to this common symptom.23 Deficits that persist for as long as 20 years posttreatment have been documented among cancer survivors.56 The risk for long-term, persistent cognitive impairment is likely related to multiple factors, including physiologic, genetic, psychological, sociodemographic, and lifestyle factors.23 Cancer treatments may accelerate biologic processes related to aging, including cognitive aging.2 Inflammatory pathways24 or dysregulation of multiple biologic systems57 have been hypothesized as underlying mechanisms for long-term cognitive impairment. Given the significant proportion of women with breast cancer who may benefit from chemotherapy, it is reassuring for patients and clinicians that the trajectory of cognitive impairment among women randomly assigned to CT+E converges with those receiving E. However, increased impairment from pre- to posttreatment initiation observed in both groups underscores the need for clinical management of CRCI well beyond initiation of therapy, as well as the need for additional research to elucidate mechanisms and identify effective interventions. Long-term CRCI observed among women receiving E should alert clinicians to the importance of ongoing symptom monitoring among this large population of cancer survivors who receive ≥ 5 years of treatment. Survivors of breast cancer receiving E may risk suboptimal management of long-term adverse effects if endocrine therapy is assumed to have less long-term CRCI relative to CT+E.

Strengths of this study include the randomized nature of treatment assignment, its prospective design, prespecified trial objectives and end points, and use of well-validated PRO instruments. There are also some limitations. Patient-reported cognitive impairment has been criticized for its lack of association with neuropsychological performance, though also lauded for greater sensitivity to the subtle effects of chemotherapy on cognition58 and associations with neuroimaging.60 Missing PRO data at baseline and early assessments, and attrition, particularly for long-term follow-up assessments at 24 and 36 months, may have resulted in a biased sample, though overall retention was good. The per-protocol analysis may introduce bias through excluding women who opted out of treatment assigned through randomization, though our intent-to-treat analysis yielded similar results. Chemotherapy and endocrine therapy regimens were chosen by clinician discretion, thus introducing variability in chemotherapeutic agents received and duration of treatment. We estimated that most women receiving CT+E completed chemotherapy by approximately 3 months, though, due to varying regimen lengths and potential dose delays, the interval between chemotherapy completion and PRO administration may have varied.

In conclusion, this report, based on a sample of women with breast cancer randomly assigned to either CT+E or E and then prospectively assessed for 3 years, confirmed greater cognitive impairment acutely during treatment. Both CT+E and E were associated with lingering impairment, underscoring the need for ongoing attention to CRCI, which appears to stabilize at 12 months and beyond. In quantifying the unique contribution of chemotherapy to CRCI, our findings underscore the value of precision-guided care in identifying women most likely to benefit from chemotherapy and sparing those who are unlikely to benefit from treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ECOG-ACRIN) Cancer Research Group (Peter O’Dwyer MD; and Mitchell D. Schnall, MD, PhD, group co-chairs). We acknowledge Jeff Abrams, MD; Sheila Taube, PhD; and Ann O’Mara, PhD, National Cancer Institute, for their support of the trial at its inception and development. We thank the staff at the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group Operations Office in Boston and the Cancer Trials Support Unit. We acknowledge Mary Lou Smith, patient advocate, for her assistance with trial design and interpretation of results. We thank the late Robert L. Comis, MD, former chair of ECOG and co-chair of ECOG-ACRIN, for his leadership.

Appendix

FIG A1.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Perceived Cognitive Impairment change score from baseline: intent to treat analysis trajectory. ITT, intent to treat; PP, per protocol.

TABLE A1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of TAILORx Trial Sample, PRO Eligible Sample, per Protocol PRO Eligible Sample, and per Protocol PRO Eligible Sample With Baseline Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Assessments

TABLE A2.

FACT-Cog Scale Descriptive Statistics by Treatment Arm

TABLE A3.

Descriptive Statistics for Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Perceived Cognitive Impairment by Assessment Time Point and Type of Chemotherapy (ie, per protocol; only patients randomly assigned to and receiving chemotherapy)

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, December 4-8, 2018; and the ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 1-5, 2012.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the following awards to the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group: Grants No. CA189828, CA180820, CA180794, CA180790, CA180795, CA180799, C180801, CA180816, CA180821, CA180838, CA180822, CA180844, CA180847, CA180857, CA180864, CA189867, CA180868, CA189869, CA180888, CA189808, CA189859, CA190140, and CA180863; the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (Grants No. 015469 and 021039); the Breast Cancer Research Foundation; the Susan G. Komen Foundation; the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (stamp issues by the US Postal Service); and Genomic Health.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

See accompanying Editorial on page 1871

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Lynne I. Wagner, Robert J. Gray, Joseph A. Sparano, Charles E. Geyer, Kathleen I. Pritchard, Daniel F. Hayes, E. Claire Dees, Worta J. McCaskill-Stevens, Lori M. Minasian, David Cella

Financial support: Joseph A. Sparano, Worta J. McCaskill-Stevens

Provision of study material or patients: Joseph A. Sparano, Kathy S. Albain, Kathleen I. Pritchard, Daniel F. Hayes

Collection and assembly of data: Robert J. Gray, Amye J. Tevaarwerk, Matthew P. Goetz, Kathleen I. Pritchard, Charles E. Geyer, E. Claire Dees

Data analysis and interpretation: Lynne I. Wagner, Robert J. Gray, Timothy J. Whelan, Sofia F. Garcia, Betina Yanez, Amye J. Tevaarwerk, Ruth C. Carlos, Kathy S. Albain, John A. Olson Jr, Matthew P. Goetz, Charles E. Geyer, Worta J. McCaskill-Stevens, Lori M. Minasian, George W. Sledge Jr, David Cella

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Patient-Reported Cognitive Impairment Among Women With Early Breast Cancer Randomly Assigned to Endocrine Therapy Alone Versus Chemoendocrine Therapy: Results From TAILORx

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Lynne I. Wagner

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Robert J. Gray

Research Funding: Agios, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Roche, Genomic Health, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Ortho, Onyx, Pfizer, Sequenta, Syndax, Novartis, Takeda, AbbVie, Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme

Joseph A. Sparano

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Metastat

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Celldex, Pfizer, Prescient Therapeutics, Juno Therapeutics, Merrimack, Adgero Biopharmaceuticals, Cardinal Health, Prescient Therapeutics (Inst), Deciphera (Inst), Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst), Novartis (Inst)

Research Funding: Merrimack (Inst), Radius Health (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Menarini Silicon Biosystems, Roche, Adgero Biopharmaceuticals, Myriad Genetics, Pfizer, AstraZeneca

Timothy J. Whelan

Research Funding: Genomic Health

Betina Yanez

Employment: Vibrent Health (I)

Amye J. Tevaarwerk

Other Relationship: Epic Systems (I)

Ruth C. Carlos

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GE Healthcare

Other Relationship: Journal of the American College of Radiology (Inst)

Kathy S. Albain

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Pfizer, Myriad Genetics, Genomic Health, Agendia, Roche

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics, Seattle Genetics (Inst)

Other Relationship: Puma Biotechnology

John A. Olson Jr

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Core Prognostex

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: (1) Device for Containing and Analyzing Surgically Excised Tissue and Related Methods. US Patent No. 7,172,558. Date issued: February 2, 2007. (2) Expression and Function of GPR64/ADGRG2 in Endocrine Systems and Methods to Target It Therapeutically. US Patent Application No: 15/589,526. Date filed: May 8, 2017 (pending).

Matthew P. Goetz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly, bioTheranostics, Genomic Health, Novartis, Eisai, Sermonix, Context Therapeutics, Pfizer

Research Funding: Eli Lilly, Pfizer

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: (1) Methods and Materials for Assessing Chemotherapy Responsiveness and Treating Cancer. (2) Methods and Materials for Using Butyrylcholinesterases to Treat Cancer. (3) Development of Human Tumor Xenografts From Women With Breast Cancer Treated With Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (Inst).

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly

Kathleen I. Pritchard

Honoraria: Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, Eisai, Genomic Health International, Myriad Genetics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, Eisai, Genomic Health International, Myriad Genetics

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, Eisai, Genomic Health International, Myriad Genetics

Daniel F. Hayes

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncImmune, InBiomotion

Consulting or Advisory Role: Cepheid, Freenome, Cellworks, CVS Caremark Breast Cancer Expert Panel, Agendia, Epic Sciences, Salutogenic Innovations

Research Funding: AstraZeneca (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Merrimack (Inst), Menarini Silicon Biosystems (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Puma Biotechnology (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties from licensed technology. Inventor/co-inventor on the following two patents: (1) Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Patent No. US 8,790,878 B2. Date of Patent: July 29, 2014. Applicant Proprietor: University of Michigan. (2) Circulating Tumor Cell Capturing Techniques and Devices. Patent No. US 8,951,484 B2. Date of Patent: February 10, 2015. Applicant Proprietor: University of Michigan. (3) Holds patent No. 05725638.0-1223-US2005008602: A Method for Predicting Progression Free and Overall Survival at Each Follow Up Timepoint During Therapy of Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Using Circulating Tumor Cells.

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Menarini Silicon Biosystems

Other Relationship: Menarini, UpToDate

Charles E. Geyer

Research Funding: Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AbbVie, Roche, Daiichi-Sankyo, AstraZeneca

E. Claire Dees

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis (I), STRATA, G1 Therapeutics

Research Funding: Novartis, Roche, Bayer, Pfizer, Merck, Eli Lilly, Cerulean Pharma, H3 Biomedicine, Meryx Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: G1

George W. Sledge Jr

Leadership: Syndax, Tessa Therapeutics

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Syndax, Tessa Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Radius Health, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Symphogen, Synaffix, Syndax, Verseau Therapeutics

Research Funding: Roche (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Radius Health, Verseau Therapeutics, Tessa Therapeutics

David Cella

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: FACIT.org

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Novartis, PledPharma, Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Corcept Therapeutics, IDDI, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Ipsen

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Bayer (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), PledPharma (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Regeneron (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Ipsen, PledPharma

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wefel JS, Kesler SR, Noll KR, et al. Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:123–138. doi: 10.3322/caac.21258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahles TA, Root JC, Ryan EL. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: An update on the state of the science. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3675–3686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, et al. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: Results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2292–2299. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid-Arndt SA, Yee A, Perry MC, et al. Cognitive and psychological factors associated with early posttreatment functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:415–434. doi: 10.1080/07347330903183117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvio L, Peugeot M, Bruns GL, et al. Measures of cognitive function and work in occupationally active breast cancer survivors. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:219–227. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181d0bef7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brezden CB, Phillips KA, Abdolell M, et al. Cognitive function in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2695–2701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.14.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, et al. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:485–493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Dam FS, Schagen SB, Muller MJ, et al. Impairment of cognitive function in women receiving adjuvant treatment for high-risk breast cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:210–218. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: Impact of age and cognitive reserve. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4434–4440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermelink K, Untch M, Lux MP, et al. Cognitive function during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Results of a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal study. Cancer. 2007;109:1905–1913. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.6624. Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, et al: Longitudinal trajectory and characterization of cancer-related cognitive impairment in a nationwide cohort study. J Clin Oncol 36:3231-3239, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins B, Mackenzie J, Stewart A, et al. Cognitive effects of hormonal therapy in early stage breast cancer patients: A prospective study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:811–821. doi: 10.1002/pon.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurria A, Somlo G, Ahles T. Renaming “chemobrain”. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:373–377. doi: 10.1080/07357900701506672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wefel JS, Saleeba AK, Buzdar AU, et al. Acute and late onset cognitive dysfunction associated with chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:3348–3356. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, et al. Cognitive function in breast cancer patients prior to adjuvant treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9686-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tager FA, McKinley PS, Schnabel FR, et al. The cognitive effects of chemotherapy in post-menopausal breast cancer patients: A controlled longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellon SA, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. Neurocognitive performance in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy and tamoxifen. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:955–969. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibayama O, Yoshiuchi K, Inagaki M, et al. Association between adjuvant regional radiotherapy and cognitive function in breast cancer patients treated with conservation therapy. Cancer Med. 2014;3:702–709. doi: 10.1002/cam4.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shilling V, Jenkins V, Morris R, et al. The effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on cognition in women with breast cancer—Preliminary results of an observational longitudinal study. Breast. 2005;14:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer JL, Trotter T, Joy AA, et al. Cognitive effects of tamoxifen in pre-menopausal women with breast cancer compared to healthy controls. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:275–282. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schilder CM, Seynaeve C, Beex LV, et al. Effects of tamoxifen and exemestane on cognitive functioning of postmenopausal patients with breast cancer: Results from the neuropsychological side study of the tamoxifen and exemestane adjuvant multinational trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1294–1300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen BT, Jin T, Patel SK, et al. Gray matter density reduction associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4911-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahles TA, Root JC. Cognitive effects of cancer and cancer treatments. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:425–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz PA, Bower JE, Kwan L, et al. Does tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) play a role in post-chemotherapy cerebral dysfunction? Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S99–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merriman JD, Sereika SM, Brufsky AM, et al. Trajectories of self-reported cognitive function in postmenopausal women during adjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26:44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2005–2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jim HSL, Phillips KM, Chait S, et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in breast cancer survivors previously treated with standard-dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3578–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bower JE, Wiley J, Petersen L, et al. Fatigue after breast cancer treatment: Biobehavioral predictors of fatigue trajectories. Health Psychol. 2018;37:1025–1034. doi: 10.1037/hea0000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella D, Fallowfield L, Barker P, et al. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the ATAC (“Arimidex”, tamoxifen, alone or in combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wagner L, Cella D: Quality of life and psychosocial issues, in Bonadonna G, Hortobagyi G and Valagussa P, (eds 3): Textbook of Breast Cancer: A Clinical Guide to Therapy, Vol. 3. New York, NY, Taylor & Francis Group, 2006:345. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH, et al. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA perspective. Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S125–S137. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehnert A, Scherwath A, Schirmer L, et al. The association between neuropsychological impairment, self-perceived cognitive deficits, fatigue and health related quality of life in breast cancer survivors following standard adjuvant versus high-dose chemotherapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwin PJ, Black JT, Bordeleau LJ, et al. Health-related quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer—Taking stock. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:263–281. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner LI, Sweet J, Butt Z, et al. Measuring patient self-reported cognitive function: Development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Cognitive Function Instrument. J Support Oncol. 2009;7:W32–W39. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs SR, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M, et al. Evaluation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy cognitive scale with hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2341. Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al: Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: A patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. J Clin Oncol 25:5106-5112, 2007 [Erratum: J Clin Oncol 26:1018, 2008] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, et al. How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: A PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10) Suppl:S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fallowfield LJ, Leaity SK, Howell A, et al. Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: Validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-B. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55:187–197. doi: 10.1023/a:1006263818115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gotay CC, Pagano IS. Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC): A newly proposed brief questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yost KJ, Eton DT. Combining distribution- and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences: The FACIT experience. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:172–191. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheung YT, Foo YL, Shwe M, et al. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the functional assessment of cancer therapy: Cognitive function (FACT-Cog) in breast cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, et al. Cognitive complaints in survivors of breast cancer after chemotherapy compared with age-matched controls: An analysis from a nationwide, multicenter, prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:506–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reference deleted.

- 49.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breckenridge LM, Bruns GL, Todd BL, et al. Cognitive limitations associated with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors in employed breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;21:43–53. doi: 10.1002/pon.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shilling V, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, et al. The effects of hormone therapy on cognition in breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Underwood EA, Jerzak KJ, Lebovic G, et al. Cognitive effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy in older women treated for early-stage breast cancer: A 1-year longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3035–3043. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Underwood EA, Rochon PA, Moineddin R, et al. Cognitive sequelae of endocrine therapy in women treated for breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4627-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jenkins V, Shilling V, Deutsch G, et al. A 3-year prospective study of the effects of adjuvant treatments on cognition in women with early stage breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:828–834. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai J-S, Wagner LI, Jacobsen PB, et al. Self-reported cognitive concerns and abilities: Two sides of one coin? Psychooncology. 2014;23:1133–1141. doi: 10.1002/pon.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koppelmans V, Breteler MMB, Boogerd W, et al. Neuropsychological performance in survivors of breast cancer more than 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1080–1086. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McEwen BS. Biomarkers for assessing population and individual health and disease related to stress and adaptation. Metabolism. 2015;64(suppl 1):S2–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt073. Ganz PA, Kwan L, Castellon SA, et al: Cognitive complaints after breast cancer treatments: Examining the relationship with neuropsychological test performance. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:791-801, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Apple AC, Schroeder MP, Ryals AJ, et al. Hippocampal functional connectivity is related to self-reported cognitive concerns in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]