Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic. Governments have implemented combinations of “lockdown” measures of various stringencies, including school and workplace closures, cancellations of public events, and restrictions on internal and external movements. These policy interventions are an attempt to shield high-risk individuals and to prevent overwhelming countries' healthcare systems, or, colloquially, “flatten the curve.” However, these policy interventions may come with physical and psychological health harms, group and social harms, and opportunity costs. These policies may particularly affect vulnerable populations and not only exacerbate pre-existing inequities but also generate new ones.

Methods

We developed a conceptual framework to identify and categorize adverse effects of COVID-19 lockdown measures. We based our framework on Lorenc and Oliver's framework for the adverse effects of public health interventions and the PROGRESS-Plus equity framework. To test its application, we purposively sampled COVID-19 policy examples from around the world and evaluated them for the potential physical, psychological, and social harms, as well as opportunity costs, in each of the PROGRESS-Plus equity domains: Place of residence, Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital, Plus (age, and disability).

Results

We found examples of inequitably distributed adverse effects for each COVID-19 lockdown policy example, stratified by a low- or middle-income country and high-income country, in every PROGRESS-Plus equity domain. We identified the known policy interventions intended to mitigate some of these adverse effects. The same harms (anxiety, depression, food insecurity, loneliness, stigma, violence) appear to be repeated across many groups and are exacerbated by several COVID-19 policy interventions.

Conclusion

Our conceptual framework highlights the fact that COVID-19 policy interventions can generate or exacerbate interactive and multiplicative equity harms. Applying this framework can help in three ways: (1) identifying the areas where a policy intervention may generate inequitable adverse effects; (2) mitigating the policy and practice interventions by facilitating the systematic examination of relevant evidence; and (3) planning for lifting COVID-19 lockdowns and policy interventions around the world.

Keywords: COVID-19, Equity, Inequity, Adverse effects, Public health, Impact assessment

What is new?

Key findings

-

•

COVID-19 lockdown policies particularly affect vulnerable populations, exacerbating pre-existing inequities and generating new ones.

-

•

We found examples of inequitably distributed adverse effects for each COVID-19 lockdown policy example, stratified by LMIC and HIC, in every equity domain.

What this adds to what was known?

-

•

We developed a conceptual framework for identifying the equity harms of COVID-19 policy interventions.

What is the implication and what should change now?

-

•

Systematically applying this framework can help to identify the areas where a policy intervention may generate inequitable adverse effects; mitigate policy and practice interventions by facilitating the systematic examination of relevant evidence; and plan for lifting COVID-19 lockdowns around the world.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the novel viral zoonosis Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. Countries have reacted to the virus by putting in place different public health interventions. These interventions are intended to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19, while also mitigating the potentially disastrous impact on health systems. Each country is choosing different combinations of policy interventions, some of which are more or less stringent [2]. The menu of policy options includes school closures; workplace closures; public event cancellations; public transport closures; restrictions on internal movement; and international travel controls. Combinations of these policy options are colloquially being referred to as “lockdown.”

The benefits of these policy options with respect to reducing transmission and flattening the COVID-19 epidemic curve have been enumerated elsewhere [3]. However, some of the adopted interventions risk generating or exacerbating inequities [4]. There is evidence for both the inequitable distribution of harms accrued due to pandemics and due to the policy interventions in response to them; there is thus a need for pandemic preparedness and responses to adopt an equity and social justice lens [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. In their comment in Nature Medicine on March 26, 2020, Wang and Tang stated “Solid evidence for tackling health inequities during the COVID-19 outbreak is in urgent need. The scarcity of health-equity assessment during the current outbreak will halve the disease-control efforts [5].” Although there have been analyses of the wider impacts of the pandemic [11], there is a lack of evidence-informed tools for detailed and systematic analysis of the type and extent of inequities that may be created or deepened as a result of the actions taken to address the pandemic. Such tools are needed to identify and implement mitigation strategies and to inform an equitable pandemic response.

The aim of this study was to develop a conceptual framework to help various policy actors, including national and local governments, public health professionals, nongovernmental organizations, and researchers, systematically to analyze the health, psychological, social, and opportunity cost harms of COVID-19 policies according to the Cochrane PROGRESS-Plus equity algorithm. We worked through specific COVID-19 policy examples for each of the PROGRESS-Plus equity domains to demonstrate how the conceptual framework could be used. We identified the areas where there may be an inequitably distributed burden of adverse effects caused by COVID-19 public health interventions or where COVID-19 interventions may widen pre-existing inequities [12].

2. Methods

We built on two previously developed frameworks for assessing the adverse and inequitable effects of public health interventions [4,9]. The Lorenc and Oliver framework describes five categories of harms that may occur when implementing public health interventions without mitigation strategies: direct health harms, psychological harms, equity harms, group and social harms, and opportunity costs [9]. We expanded on this by subdividing the concept of “equity harms” into the domains specified by the PROGRESS-Plus health equity framework: Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital, Sexual orientation, Age, and Disability [6]. After disaggregating the “equity” domain, we cross-tabulated the PROGRESS-Plus categories with the remaining four adverse effects domains: direct health harms, psychological harms, group and social harms, and opportunity cost harms. This approach allowed us to 1) identify the relevant peer-reviewed and gray literature of previously known inequities and emerging evidence of the impacts of the lockdown measures, 2) conceptualize how specific measures may exacerbate, or lead to, inequities, and 3) relate these considerations to potential mitigation measures.

Conceptual frameworks represent a network of interlinked concepts in a particular area. They can provide a structure for understanding a phenomenon or subject [13]. Polit and Beck asserted that frameworks can in fact make research more comprehensible and generalizable [14]. They are a way to bring together many components on a complex topic, such as COVID-19-related inequity. We drew from the literature on health equity impact assessments (HEIAs) to develop and complete a “proof-of-concept” framework. The World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health highlights the importance of undertaking HEIAs during the policy development [15]. We iteratively and reflexively developed our framework to cover two dimensions: 1) socially stratifying equity factors and 2) types of harms. These frameworks were developed iteratively through application and testing in systematic reviews, epidemiologic studies, and policy analyses [4,9,12]. After testing our framework on emergent reports of COVID-19 equity harms, we refined it to capture policies (rather than programs); to function on disparate geopolitical levels; and to capture mitigation strategies [16].

After we developed the framework, we purposively selected from the many emergent reports of COVID-19 policy interventions causing equity harms to demonstrate the application of the framework. We searched the peer-reviewed and emergent COVID-19 literature to identify the pre-existing evidence on inequities related to the specific harms associated with a particular lockdown policy. We conceptualized the interplay between a given policy, and its equity harms, by drawing on this literature, and through expert consultation and consensus discussions. We identified examples of ongoing efforts to mitigate the inequity effects generated by the lockdown measures through expert consultation with the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group. Systematic review of the literature was not performed given 1) the examples were intended to be illustrative but not exhaustive, 2) ongoing research and evaluation is needed to measure actual equity harms, and 3) the need to provide evidence-informed but timely tools in the context of a rapidly evolving situation to draw attention to inequities.

We included examples of COVID-19 policies to demonstrate how the new framework could be used. We purposively selected our examples of policy interventions from emergent COVID-19 literature and media reports to cover: each WHO region, a range of lenient to stricter policies, one low- or middle-income country (LMIC) and high-income country (HIC) example per PROGRESS-Plus domain, and measures being monitored by the Oxford COVID-19 policy tracker [2]. We applied our framework to each COVID-19 policy case study.

3. Results

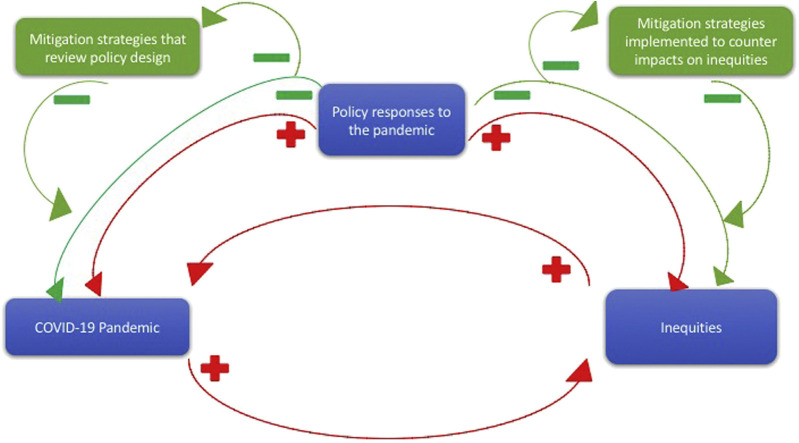

Construction and application of the framework demonstrated that each adverse effect, and each equity domain, can interact with, worsen, and be worsened by others. For example, equity factors such as age, place of residence, socioeconomic status (SES), ethnicity, and occupation may all contribute to physical risk of Covid-19 but also be risk factors for disproportionately feeling the effects of certain policy interventions (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The pandemic exacerbates existing inequities, which can in turn exacerbate the pandemic, for example, low SES individuals need to work rather than remain in lockdown. Policy responses have the ability to reduce the peak of the pandemic, or, if poorly designed or implemented, increase it. They also have the potential to increase or reduce inequities. Mitigation strategies can be implemented at the review stage leading to a change in the policy design to prevent or reduce the risk of inequitable harms, or be implemented alongside the lockdown policies to counter or reduce the anticipated impacts on inequities. Both approaches may be taken; this may introduce a feedback loop that targets reductions in the pandemic itself, and health and societal inequities.

Table 1 uses a number of examples of COVID-19 policies to illustrate four types of harms across the domains specified by the PROGRESS-Plus health equity framework. It also provides examples of mitigation interventions. An expanded version of Table 1 can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

A conceptual framework for identifying equity harms due to COVID-19 policies

| Country | COVID-19 policies | Evidence of potential harms |

Interventions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Psychological | Group/social | Opportunity cost | ||||

| Place of residence | LMIC | People living in shanty towns in South Africa have been targeted [17] | Infection [[18], [19], [20]] | Mental health [20] | Street vendors; informal workers [21,22] | Economic loss; unemployment [23,24] | Topping up child support grants [25] |

| HIC | Closure of green spaces [26,27] | Child injuries [28] | Mental health [29,30] | Homeless [31] | Inactivity [32,33] | Parks [26]; housing [34] | |

| Race, ethnicity, culture, and language | LMIC | Lebanon's government quarantined refugee camps [35] | Decreased medical care [36] | Anxiety, PTSD [[37], [38], [39]] | Stigma, disenfranchisement [27,40] | Forgoing more effective interventions [24] | Provide food, medical supplies [41,42] |

| HIC | Sweden's COVID-19 cases proliferated among immigrants [43] | COVID-19 cases [43] | Stigma [44] | Access to expert advice [45] | Population level alternatives [46] | Make housing available [44] | |

| Occupation | LMIC | Informal workers in Nigeria and Kenya could not work [47,48] | Food insecurity [49] | Stigma [50] | Resistance and protests [51] | Economic output [52] | Cash payments [48] |

| HIC | Essential workers at higher risk [53] | COVID-19 cases [54] | Stress [54,55] | Eviction [56] | Other illnesses [57] | Protect workers [58,59] | |

| Gender/sex | LMIC | School closures have unique impacts on girls [60] | Food insecurity [61] | Child marriage [62]; mental health [61,63] | Gendered educational attainment [64,65] | Foregoing education [66] | Representation [67] |

| HIC | In the United Kingdom, home is unsafe for some during lockdown [68] | Abuse [[68], [69], [70]] | Abuse [69,71] | Migrant women [72] | Morbidity [73,74] | Representation [59,75] | |

| Religion | LMIC | Indonesia had high rates of COVID-19 [76] | Smoking risks [77] | Stigma [78,79] | Unhealthy commodities [80] | Displacing effective interventions [81,82] | Banning mudik [76] |

| HIC | Certain UK religious groups may not be receiving COVID-19 news [83,84] | Hate crimes, assaults [84] | Stigma [85] | Preventing traditional practices [86] | Foregoing faith-based interventions [87] | Faith organizations may provide help [87] | |

| Education | LMIC | 90% of learners are out of school [88] | Food insecurity [89] | Anxiety, stress [90] | Poorer families [91] | Education [60] | Remote learning [60] |

| HIC | Most US schools closed until September [92] | Food insecurity [93] | Anxiety, stress [90] | Health workers [94] | Absenteeism [94] | “Take-out” meals [95] | |

| Socioeconomic status | LMIC | Lebanon restricted informal workers [96,97] | Food insecurity [98] | Stigma, stress [96] | Protests [99,100] | Education [101,102] | Fiscal measures [103,104] |

| HIC | New Zealand's government enforced border closures [105] | COVID-19 risk in Māori [106] | Mental health [107,108] | Māori and Pasifika [107] | Tourism sector [105] | Avoid exacerbation inequalities [109,110] | |

| Social capital | LMIC | Restrictions risk community networks [24] | Drug adherence [111] | Stress [112] | Cohesion [113,114] | Future local projects [115] | Remote support [116] |

| HIC | “Snitch lines” and fines were adopted in Ottawa, Canada [117,118] | Decrease treatment seeking [119] | Depression [120] | Stigma, decreased trust [121] | Displace more effective alternatives [122] | Remote support [116] | |

| Age | LMIC | Vaccine programs suspended in Ukraine [123] | Preventable diseases [124] | Mental health [125] | Children of poorest parents [126] | Increased inequalities [127] | Avoid suspending vaccines [12,128] |

| HIC | The United Kingdom and the United States are isolating the elderly and those living in care homes | High rates of COVID-19 [129] | Loneliness, depression [130] | Need for health and social care [131] | Staggered release [132] | Support lines [133], access to care [134] | |

| Disability | LMIC | Some South American prisons halted visits. Prevalence of disabilities is high in incarcerated people [135] | High rates of COVID-19 [136,137] | Mental health [138] | Stigma [139] | Visits reduce recidivism [138], Riots [135] | Decarceration [140] |

| HIC | Canadian children's autism therapy disrupted [141] | Risk of COVID-19 [142] | Backsliding; stress [141,143] | Regressions in skills [144] | Access to information [145] | Involve affected groups [142,146] | |

Table 1 serves as a case study for how to use this conceptual framework. A blank version is included in Supplementary Materials for readers to use themselves. Table 2 outlines the definitions of the domains that comprise the framework and are used in Table 1. We used examples of specific policies adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to demonstrate the types of evidence that may support identification of a range of equity issues and associated harms. We chose a real-world policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has relevance to each of the PROGRESS-Plus categories, including a HIC and a LMIC policy example. We also identified examples of mitigating interventions that have been attempted so far in the COVID-19 response. Not all mitigating strategies will be effective, and these proposed mitigating strategies may themselves generate a range of adverse effects that are also likely to be distributed inequitably, with many yet to be evaluated.

Table 2.

Definitions of the terms used

| Equity | The absence of avoidable and unfair differences in a particular condition or state between different groups of people. For example, health equity is the absence of avoidable and unfair differences in health outcomes [147] |

| Adverse effects (adapted from Lorenc and Oliver) [9] | |

| Physical health | Direct or indirect harms that accrue across all spheres of physical health |

| Psychological health | Direct or indirect harms that accrue across the range of mental health areas, including but not limited to depression, anxiety, stress, and psychosis |

| Group or social | Direct or indirect harms that accrue by targeting social interventions at particular groups or parts of society, thereby worsening the experience of subsets of people within a population |

| Opportunity cost | The loss of one or more option, course of action, or outcome that is incurred by selecting an alternative one |

| PROGRESS domains (adapted from O'Neill et al.) [4] | |

| Place of residence | Place of residence can mean the type of dwelling (house with a garden, flat, house of multiple occupancy, informal settlement, prison), location of dwelling (urban, suburban, rural), specialist dwelling (assisted living, care homes, hospice), or lack of dwelling (people who experience homelessness). It is linked to socio-economic status and access to outside space, public transit, infrastructure, livelihoods, and other services (e.g., health care), social cohesion, and environmental exposures [148] |

| Race, ethnicity, culture, and language | There are many health outcomes that accrue inequitably due to race, ethnicity, culture, and language. Health risks and outcomes are often stratified between ethnic groups, with worse health outcomes often observed in Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) populations. This may reflect inequities in the burdens of wider determinants of health such as employment and environmental exposures, discrimination, education, or diet. However, concepts such as inherent or biological susceptibility can be invoked to further discriminate against such groups, leading to further physical and psychological harms |

| Occupation | Occupation may refer to the status of employment—such as unemployed, part-time, “zero-hour” contract or full-time employment—or the type of employment. These have implications for health equity, with some professions or exposures being more high risk than others. Job security and the type of labor protections in place are important, particularly during times of crisis |

| Gender/sex | Biological and gender-based differences can lead to unequal distribution of disease risks, incidence and outcomes, as well as healthcare service needs. Other differences can be due to inequitable exposure to risk or protections based on sex or gender, such as through the sector of employment or legal rights, or discrimination, barriers to services, or the type and quality of service provision that is received |

| Religion | Religious affiliation, or lack thereof, can lead to inequitably exposure to harms and/or opportunities. For example religious status may affect access to health services or the appropriateness of the health service offered and received. Certain religious affiliations may experience discrimination, stigma, or even violence |

| Education | Education is known to have impact on health status not only due to its relationship with employment, and consequently, income, but also due to the colocation and embedding of other health interventions (e.g., counseling and meal programs) into educational settings. Education is a fundamental determinant of health and also an effective means of reducing health inequities. Conversely, disruption to education is an adverse mechanism for potentially increasing inequalities; partly by withdrawing the intervention from poorer families, but also because better off families are better able to fill the gap with supplemental homeschooling |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | Higher SES is associated with longer life expectancy and fewer years of poor health due to a constellation of effects including access to clean water, food security, better housing conditions, education, access to healthcare, health and communication literacy, and lower rates of stress |

| Social capital | The original PROGRESS definitions included social capital, which was defined as: “social relationships and networks. It includes interpersonal trust between members of a community, civic participation, and the willingness of members of a community to assist each other and facilitate the realization of collective community goals and the strength of their political connections, which can facilitate access to services [4].” Social capital can act as a determinant of health and also a social buffer, particularly in times of individual or population-level crisis. It can act via psychosocial pathways, and it can enhance financial support or access to resources [114]. Social capital is closely related to socioeconomic inequalities; it is important not to view social capital, which often has an individualistic focus, as an alternative to effective health, social and economic policies to reduce or even prevent inequities [149] |

| Other relevant domains: The PROGRESS domains include a “Plus” feature, which allows for the addition of specific time-dependent or condition-dependent domains. These can vary across contexts. We chose to include age and disability because of their relevance to COVID-19 outcomes [4] | |

| Age | While age itself is an unavoidable risk factor for many diseases, certain age groups can often be inequitably impacted by avoidable differences in access to services and technology and vulnerability to exploitation and to the impacts of termination or suspension of certain services such as routine healthcare services or education. Some age groups may have greater resilience or adaptability during times of crisis |

| Disability | Disability reduces access to health services [150]. These reductions in access may be exacerbated by closures, uncertainties, and reduced availability of primary care clinicians or other forms of routine care. Uncertainty in access to services can lead to psychological harms for those most dependent on them [151] |

Although each policy example and associated equity considerations provides important insights for policy design and implementation, important observations are made from examining trends across the table as a whole. For example, the same harms (food insecurity, violence, loneliness, depression, anxiety, stigma) are repeated across many groups and are exacerbated by many COVID-19 policy interventions. This is crucial; it shows that inequitable policy options may generate interactive and multiplicative harms [11,152,153]. For example, poorer women living in poorer communities are at higher risk of acquiring COVID-19 due to the need to continue working and to crowded working and living conditions. In addition, if they become infected, they are at higher risk of poor health outcome considering lower access to, and lower quality of, healthcare services. On the other hand, lockdown measures put them at higher risks of physical and mental health risks of inactivity, domestic abuse, and lost earnings. Table 1 also demonstrates that certain mitigation strategies may be implemented in response to more than one equity issue, and that certain lockdown policies may act upon multiple equity domains. Most countries have implemented a “package” of lockdown policies, and Table 1 demonstrates the need to conduct such an assessment on each component of the package, to help consider and identify how policies may interact in a way that worsens inequities to a greater extent than had any one component been implemented in isolation.

4. Discussion

We have developed a framework tool systematically to analyze the types of harms potentially induced by COVID-19 policies across different equity domains. The tool also allows for the identification of mitigation strategies.

Many of the included policies, while providing benefits in addressing the pandemic, are simultaneously likely to be generating new inequities and worsening pre-existing ones. Systematically adopting the proposed framework may help to identify inequitably distributed adverse effects, thereby aiding in the development of mitigating policy options in these areas. It may also help with considering the beneficial or harmful impacts of partially or wholly lifting lockdowns, as well as the impacts of the economic recession that will follow the acute response to the pandemic. In the future, it might also provide an input into decisions about when and how to return to lockdown in a second or third pandemic wave.

Ideally this exercise could be undertaken using systematically identified, relevant academic evidence, and would have been undertaken as lockdown policies were being planned and implemented. But in many contexts, the most relevant evidence is not open access, not complete, or nonexistent. Because of the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic, gray literature, government reports, media articles, and social media posts may be the acceptable choices of “evidence” of potential impacts in some circumstances for such high-speed impact assessments [154]. Reports of increased numbers of domestic abuse victims, for example, are important to include in this exercise, even if there is no appropriate systematic review, RCT, or study that has been undertaken on COVID-19 and abuse. Indeed, research on equity is not prioritized under the urgent conditions of the pandemic. Thus, as with any complex public health problem, decisions about interventions integrate the best available evidence with theory and expert judgment [155,156]. Rapid reviews of literature, including research into the impacts of COVID-19 policy interventions on equity, are ongoing, and Cochrane and others are compiling real-time lists of relevant evidence as it becomes available (Table 3 ). This view is consistent with that of others working to develop COVID-19 policy recommendations using the precautionary principle to protect groups likely to be disproportionately affected [59,157].

Table 3.

COVID-19 evidence to consider when applying this framework to different contexts

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Cochrane COVID Rapid Reviews website | Providing evidence to front-line staff, policy makers, and researchers |

| Evidence Aid | A list, by topic, of emerging literature on COVID-19, including academic research and guidance |

| NEJM COVID Serieshttps://www.nejm.org/coronavirus | A collection of articles and other resources on the Coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak, including clinical reports, management guidelines, and commentary |

| EPPI-Mapper | COVID-19: living map of the evidence—EPPI-Mapper, a living map of published evidence related to COVID-19 |

| https://covid-evidence.org/ | COVID-evidence is a continuously updated database of the worldwide available evidence on interventions for COVID-19 |

| https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ | International prospective register of systematic review protocols, which is fast-tracking COVID-19 review protocols for reviews concerning humans and animals |

| https://www.epistemonikos.cl/living-evidence/ | Living evidence Repository for COVID-19 by Epistemonikos, a nonprofit |

Table 3 lists resources that could help in rapidly assessing COVID-19 emerging literature for local, regional, and national contexts, across multiple topics. These sources are live at the time of writing.

In our framework, we have in some cases selected supranational examples—such as people living with disabilities who experience incarceration across South America—and in some cases, we have chosen neighborhood-level examples—such as the Swedish–Somali neighborhood in Stockholm. This is intentional and serves as a reminder that an exclusively national-level lens can miss the magnifying impact of important global trends, or, conversely, overlook local-level heterogeneity.

Some governments, once they have been made aware of inequities, have attempted to marshal the fast-moving COVID-19 response to mitigate them. In the United Kingdom, the government has recently made methadone available at pharmacies without a prescription [158]. After initially banning alcohol sales, a French local authority changed their policy after fears that alcohol dependency meant dangerous detoxification alone during the pandemic [159]. The Swedish government found that multigenerational housing combined with risk groups was causing increased rates of COVID-19 in the Swedish–Somali community and so made housing available for high-risk members of the Swedish–Somali community [160]. In Spain, universal basic income is being considered as an effort to avert Coronavirus economic disaster [161]. However, more can always be done; domestic abuse is increasing due to lockdown requirements for victims to stay home with their abusers [162], and, in Canada, asylum seekers are being turned away due to international travel restrictions [163]. For every example of a mitigating policy intervention, there seem to be many more groups whose needs have been neglected.

The goals, timing, and outcome prioritization of COVID-19 policy interventions reflect political considerations. For example, political orientation may be reflected in an emphasis on personal responsibility and individual-level behavior change interventions (e.g., an exclusive focus on individual hygiene behaviors) as opposed to population-level measures. Similarly, governments with neoliberal orientations may prioritize interventions that preserve the economy. This may manifest itself in political choices to have less stringent or shorter lockdown policies, or in how long it took to lockdown in the first instance. Some of these market-oriented decisions may encourage inequities. Even choices aiming to protect health services may inadvertently increase existing inequities in care-seeking and health care use [164]. The framework presented here may also serve as a tool to advocate for more attention to be given to equity issues in contexts where they receive less political priority, by exposing unfair and unjust harms.

The nature of inequities is that they coexist across different levels of society and can incur interactive and multiplicative effects among the most disadvantaged [165]. This can be shown by the repetition of inequities across Table 1. For example, inequitable distributions of education disruptions were highlighted in the gender category in LMICs and also in the education category in LMICs and HICs. The impact of loneliness occurs multiple times as well. The pandemic will likely exacerbate these inequities, tipping those groups already on the margins of society, economic viability, and survival, over a cliff-edge of uncertainty and life-changing adverse effects.

There is a serious risk in the COVID-19 pandemic in LMICs bowing to international pressure to make the same policy choices as HICs. This may not be appropriate in all contexts because of the variations in baseline risk, resources, health, and other system-level factors [166]. Adopting many of the same policy options, such as “staying at home” is effectively impossible in many contexts, such as informal settlements, crowded dwellings, and those without access to potable water or latrines. The country context will strongly mediate the effects of COVID-19 policy options; the same policies may generate different burdens, and patterns, of inequities in different countries because of contextual and other variations [167]. In considering this, a wide definition of context should be adopted, which could include the socio-economic characteristics of populations, culture, ethnicity, geography, legal environments, health and other systems, social norms, community support mechanisms, and many other considerations, which may affect the implementation and effectiveness of interventions [167].

Policy makers should be actively taking these equity groups into account when choosing their COVID-19 policy packages and how they are implemented. When making decisions about COVID-19 policy options, governments should adopt an approach that considers both the benefits gained in transmission reduction and the harms accrued (and to whom). When the first and subsequent waves of COVID-19 are dealt with in a reactionary way, this framework can inform the strengthening of pandemic preparedness plans proactively in the future. These decisions could be informed by decision analytic approaches to encourage costs and benefits options to be compared across multiple domains [168].

There are several limitations of this conceptual framework. First, any effort to mitigate inequities risks incurring them. It may also be difficult to operationalize an equity lens for those populations or groups that fall between or among categories. One way to consider particularly vulnerable groups would be to conduct this exercise for a single vulnerable population, such as displaced persons, and work through the entire table for that specific population.

It must also be remembered that the potential inequitable effects of policies that we identify, and inequities in outcomes, in general reflect underlying structural inequities, which the pandemic has brought into sharper relief. Addressing the underlying social determinants of inequity in parallel is itself an essential intervention to mitigate the effects of this and future pandemics [169].

Although this framework represents an approach to assessing potential equity concerns, it does not enumerate all, or even most, areas in which equity concerns may exist. Rather, it is a starting point to encourage others to work toward cataloging unintended consequences of COVID-19 using an equity lens. Although our approach is in no way comprehensive, it may be a helpful tool to use in different settings. It may also be helpful as a way of considering the applicability of COVID-19 policies and other interventions across different contexts. This framework is also not COVID-19 specific. We would encourage the thoughtful and deliberate consideration of inequities as best practice in policy-making, even—or indeed especially—in a global crisis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rebecca E. Glover: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. May C.I. van Schalkwyk: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Elie A. Akl: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Elizabeth Kristjannson: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Tamara Lotfi: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Jennifer Petkovic: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Mark P. Petticrew: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Kevin Pottie: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Peter Tugwell: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Vivian Welch: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

This analysis was funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme through its core support to the Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit (Project No: PR-PRU-1217-20602). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Footnotes

Funding sources: This study was funded by the NIHR Policy Research Program through its core support to the Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit (Project No: PR-PRU-1217-20602). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of interests: All authors declared no competing interests.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.004.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available at.

- 2.Coronavirus government response tracker. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker Available at.

- 3.Ferguson N., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Imai N., Ainsley K., Baguelin M. Imperial College London; London: 2020. Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand [Internet] p. 20.https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk:8443/bitstream/10044/1/77482/8/2020-03-16-COVID19-Report-9.pdf Report No.: 9. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Neill J., Tabish H., Welch V., Petticrew M., Pottie K., Clarke M. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z., Tang K. Combating COVID-19: health equity matters. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):458. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0823-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenshine P., Reingold A., Egerter S., Mockenhaupt R., Braveman P., Marks J. Pandemic influenza planning in the United States from a health disparities perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 May;14:709–715. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.071301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uscher-Pines L., Duggan P.S., Garoon J.P., Karron R.A., Faden R.R. Planning for an influenza pandemic: social justice and disadvantaged groups. Hastings Cent Rep. 2007;37:32–39. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2007.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBruin D., Liaschenko J., Marshall M.F. Social justice in pandemic preparedness. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:586–591. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenc T., Oliver K. Adverse effects of public health interventions: a conceptual framework. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:288–290. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S.X., Wang Y., Rauch A., Wei F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112958. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas M., Katikireddi S.V., Taulbut M., McKee M., McCartney G. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic response. BMJ. 2020;369:m1557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenc T., Petticrew M., Welch V., Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:190. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabareen Y. Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polit D.F., Beck C.T. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Essentials of nursing research: appraising evidence for nursing practice.https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7GtP8VCw4BYC Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Povall S.L., Haigh F.A., Abrahams D., Scott-Samuel A. Health equity impact assessment. Health Promot Int. 2013;29:621–633. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davenport C., Mathers J., Parry J. Use of health impact assessment in incorporating health considerations in decision making. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(3):196–201. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkinson J., Bariyo N. Africa, Fierce enforcement of coronavirus lockdowns is stirring resentment. Wall Street J. 2020 https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-africa-fierce-enforcement-of-coronavirus-lockdowns-is-stirring-resentment-11585825403 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umuhoza S.M., Ataguba J.E. Inequalities in health and health risk factors in the Southern African development community: evidence from World health surveys. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0762-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nkosi V., Haman T., Naicker N., Mathee A. Overcrowding and health in two impoverished suburbs of Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1358. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7665-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weimann A., Oni T. A systematised review of the health impact of urban informal settlements and implications for upgrading interventions in South Africa, a rapidly urbanising middle-income Country. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3608. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitullah W. Pambazuka News: voices for freedom and justince. 2006. Street Vendors and informal trading: struggling for the right to trade [Internet]https://www.pambazuka.org/governance/street-vendors-and-informal-trading-struggling-right-trade Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resnick D. COVID-19 lockdowns threaten Africa’s vital informal urban food trade [Internet]. The Africa report. 2020. https://www.theafricareport.com/26003/covid-19-lockdowns-threaten-africas-vital-informal-urban-food-trade/ Available at.

- 23.Lima N.N.R., de Souza R.I., Feitosa P.W.G., Moreira J.L., da Silva C.G.L., Neto M.L.R. People experiencing homelessness: their potential exposure to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112945. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corburn J., Vlahov D., Mberu B., Riley L., Caiaffa W.T., Rashid S.F. Slum Health: Arresting COVID-19 and Improving well-being in urban informal settlements. J Urban Health. 2020;97:348–357. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassier I., Budlender J., Leibbrandt M., Zizzamia R. South Africa can - and should -top up child support grants to avoid a humanitarian crisis. The Conversation. 2020. https://theconversation.com/south-africa-can-and-should-top-up-child-support-grants-to-avoid-a-humanitarian-crisis-135222 Available at.

- 26.Yglesias M. The case for reopening America’s parks. Vox. 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/30/21232696/reopen-parks-coronavirus-covid-19 Available at.

- 27.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sengoelge M., Hasselberg M., Ormandy D., Laflamme L. Housing, income inequality and child injury mortality in Europe: a cross-sectional study. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40:283–291. doi: 10.1111/cch.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker M.G., Barnard L.T., Kvalsvig A., Verrall A., Zhang J., Keall M. Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. Lancet. 2012;379:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Promoting Mental Health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice. World Health Organization; 2005. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/MH_Promotion_Book.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on homelessness. European Public Health Alliance; 2020. https://epha.org/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-on-homelessness/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartig T., Astell-Burt T., Bergsten Z., Amcoff J., Mitchell R., Feng X. Associations between greenspace and mortality vary across contexts of community change: a longitudinal ecological study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74:534–540. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-213443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bratman G.N., Anderson C.B., Berman M.G., Cochran B., de Vries S., Flanders J. Nature and mental health: an ecosystem service perspective. Sci Adv. 2019;5(7):eaax0903. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.London’s rough sleepers to be offered hotel beds to self isolate. Mayor of London; 2020. https://www.london.gov.uk/press-releases/mayoral/rough-sleepers-to-be-offered-hotel-beds-to-isolate Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knipp K., Juma A. Lebanon faces coronavirus, poverty, hunger. DW. 2020. https://www.dw.com/en/lebanon-faces-coronavirus-poverty-hunger/a-53270955 Available at.

- 36.Chehayeb K. The New Humanitarian; 2020. How COVID-19 is limiting healthcare access for refugees in Lebanon.https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/feature/2020/04/21/Lebanon-coronavirus-refugee-healthcare Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazour F., Zahreddine N.R., Maragel M.G., Almustafa M.A., Soufia M., Haddad R. Post-traumatic stress disorder in a sample of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;72:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strømme E.M., Haj-Younes J., Hasha W., Fadnes L.T., Kumar B., Igland J. Health status and use of medication and their association with migration related exposures among Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8376-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azhari T. Al Jazeera; 2020. Lebanon municipalities “discriminate” against refugees.https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/covid-19-lebanon-municipalities-discriminate-refugees-200402154547215.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coronavirus and aid: What we’re watching. The New Humanitarian; 2020. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/04/30/coronavirus-humanitarian-aid-response Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 41.UNESCO . UNESCO; 2020. United Nations Response to COVID-19 Outbreak in Lebanon.https://en.unesco.org/news/united-nations-response-covid-19-outbreak-lebanon Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 42.MSF expands activities in Lebanon to respond to COVID-19. Medecins Sans Frontieres; 2020. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/news-stories/news/msf-expands-activities-lebanon-respond-covid-19 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Speckhard A., Mahamud O., Ellenberg M. Homeland Security Today; 2020. When Religion and Culture Kill: COVID-19 in the Somali Diaspora Communities in Sweden.https://www.hstoday.us/subject-matter-areas/counterterrorism/when-religion-and-culture-kill-covid-19-in-the-somali-diaspora-communities-in-sweden/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McElroy D. N Opinion; 2020. Sweden is making a dangerous bet on a “cultural cure” to COVID-19.https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/sweden-is-making-a-dangerous-bet-on-a-cultural-cure-to-covid-19-1.1001557 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothschild N. Foreign Policy; 2020. The Hidden Flaw in Sweden’s Anti-Lockdown Strategy.https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/21/sweden-coronavirus-anti-lockdown-immigrants/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petticrew M., Tugwell P., Kristjansson E., Oliver S., Ueffing E., Welch V. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: subgroup analysis and equity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:95. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.121095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Busari S., Salaudeen A. CNN; 2020. We don’t work, we don’t eat’: Informal workers face stark choices as Africa’s largest megacity shuts down.https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/31/africa/nigeria-lockdown-daily-wage-earners-intl/index.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nigeria: protect most vulnerable in COVID-19. Human Rights Watch; 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/14/nigeria-protect-most-vulnerable-covid-19-response Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 49.George L. World Economic Forum; 2020. COVID-19 is exacerbating food shortages in Africa.https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/africa-coronavirus-covid19-imports-exports-food-supply-chains Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiaga A.K. International Labour Organization; 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 on the informal economy in Africa and the related policy responses.https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---africa/---ro-abidjan/documents/briefingnote/wcms_741864.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nigeria virus lockdown pushes Lagos poor to the brink. France 24; 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/africa-coronavirus-covid19-imports-exports-food-supply-chains Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Onyekwena C., Ekeruche M.A. Brookings; 2020. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the Nigerian economy.https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/04/08/understanding-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-the-nigerian-economy/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu M. Visual Capitalist; 2020. The Front Line: visualizing the occupations with the highest COVID-19 risk.https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-front-line-visualizing-the-occupations-with-the-highest-covid-19-risk/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the EU/EEA and the UK – eighth update. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Stockholm: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mays H. The Guardian; 2020. NHS paramedic evicted from home for fear he would spread COVID-19.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/22/nhs-paramedic-evicted-from-home-for-fear-he-would-spread-covid-19 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenbaum L. The Untold Toll — The Pandemic’s Effects on Patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368–2371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2009984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . ECDC; Stockholm: 2020. Considerations relating to social distancing measures in response to COVID-19 – second update.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-social-distancing-measuresg-guide-second-update.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wenham C., Smith J., Morgan R. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:846–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Global Education Coalition. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition Available at.

- 61.George A.S., Amin A., de Abreu Lopes C.M., Ravindran T.K.S. Structural determinants of gender inequality: why they matter for adolescent girls’ sexual and reproductive health. BMJ. 2020;368:l6985. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Millions more cases of violence, child marriage, female genital mutilation, unintended pregnancy expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic. United Nations Population Fund; 2020. https://www.unfpa.org/news/millions-more-cases-violence-child-marriage-female-genital-mutilation-unintended-pregnancies Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 63.John N.A., Edmeades J., Murithi L. Child marriage and psychological well-being in Niger and Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1029. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7314-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Graetz N., Woyczynski L., Wilson K.F., Hall J.B., Abate K.H., Abd-Allah F. Mapping disparities in education across low- and middle-income countries. Nature. 2020;577(7789):235–238. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1872-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelly-Linden J. The Telegraph; 2020. Education in crisis: why girls will pay the highest price in the COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/women-and-girls/education-crisis-girls-will-pay-highest-price-covid-19-pandemic/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gender and education. UNICEF; 2020. https://data.unicef.org/topic/gender/gender-disparities-in-education/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gender, equity, and human rights. World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/en/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ford L. The Guardian; 2020. “Calamitous”: domestic violence set to soar by 20% during global lockdown.https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/28/calamitous-domestic-violence-set-to-soar-by-20-during-global-lockdown-coronavirus reproductive rights (developing countries). Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Townsend M. The Observer; 2020. Revealed: surge in domestic violence during COVID-19 crisis.https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/12/domestic-violence-surges-seven-hundred-per-cent-uk-coronavirus Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowcott O., Grierson J. The Guardian; 2020. Refuges from domestic violence running out of space, MPs hear.https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/28/refuges-from-domestic-violence-running-out-of-space-mps-hear Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schumacher J.A., Coffey S.F., Norris F.H., Tracy M., Clements K., Galea S. Intimate partner violence and Hurricane Katrina: predictors and associated mental health outcomes. Violence Vict. 2010;25(5):588–603. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grierson J. The Guardian; 2020. Labour calls for end to migrant benefit block during lockdown.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/21/labour-urges-give-migrants-benefits-lockdown?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Domestic abuse victim charactieristics, England and Wales: year ending March 2019. Office for National Statistics; 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2019#ethnicity Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oliver R., Alexander B., Roe S., Wlasny M. Home Office; 2019. The economic and social costs of domestic abuse.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/772180/horr107.pdf Report No.: 107. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coronavirus (COVID-19) and domestic abuse. 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): support for victims of domestic abuse.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-and-domestic-abuse/coronavirus-covid-19-support-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ratcliffe R. The Guardian; 2020. indoneisa bans Ramadan exodus amid coronavirus fears.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/21/indonesia-bans-ramadan-exodus-amid-coronavirus-fears Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Media Statement . World Health Organization; 2020. Knowing the risks for COVID-19.https://www.who.int/indonesia/news/detail/08-03-2020-knowing-the-risk-for-covid-19 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kate W. Foreign Policy; 2020. Wuhan Virus Boosts Indonesian Anti-Chinese Conspiracies.https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/01/31/wuhan-coronavirus-boosts-indonesian-anti-chinese-conspiracies/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Utomo W.P. 2020. Coronavirus, fear, and misinformation [Internet]. Indonesia at Melbourne.https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/coronavirus-fear-and-misinformation/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kantar Indonesia . 2020. COVID19 impact on indonesian attitudes & behaviours: learning for brands.https://www.kantar.com/en/Inspiration/Coronavirus/Webinar-COVID-19-Impact-on-Indonesian-Attitudes-Behaviours Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rolli N. First Quarter 2020 Earnings conference call presented at. 2020. Transcript of PM earnings conference call.https://finance.yahoo.com/news/edited-transcript-pm-earnings-conference-015715362.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Doogan N.J., Wewers M.E., Berman M. The impact of a federal cigarette minimum pack price policy on cigarette use in the USA. Tob Control. 2018;27(2):203. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hussain S. Independent; 2020. NHS officials told me Muslim households are particularly vulnerable to coronavirus – it’s important to understand why.https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/coronavirus-muslim-mosque-closure-prayer-nhs-a9411936.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Parveen N. The Guardian; 2020. Police investigate UK far-right groups over anti-Muslim coronavirus claims.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/05/police-investigate-uk-far-right-groups-over-anti-muslim-coronavirus-claims Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sherwood H. The Guardian; 2020. Jewish leaders fear ultra-orthodox Jews have missed isolation message.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/concern-ultra-orthodox-jews-not-get-message-coronavirus Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blevins J.B., Jalloh M.F., Robinson D.A. Faith and global health practice in ebola and HIV emergencies. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:379–384. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alawiyah T., Bell H., Pyles L., Runnels R.C. Spirituality and Faith-based interventions: pathways to disaster resilience for african American Hurricane Katrina survivors. J Relig Spiritual Soc Work Soc Thought. 2011;30(3):294–319. [Google Scholar]

- 88.COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse Available at.

- 89.How are we compensating for the missing daily meal? WFP; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nafungo J. 2020. Africa: virtual learning during COVID-19, who is left behind?https://allafrica.com/stories/202004080813.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chavez N., Moshtaghian A. CNN; 2020. 44 states have ordered or recommended that schools don’t reopen this academic year.https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/18/us/schools-closed-coronavirus/index.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cauchemez S., Ferguson N.M., Wachtel C., Tegnell A., Saour G., Duncan B. Closure of schools during an influenza pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:473–481. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70176-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bayham J., Fenichel E.P. Impact of school closures for COVID-19 on the US health-care workforce and net mortality: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e271–e278. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30082-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moss K., Dawson L., Long M., Kates J., Musumeci M., Cubanski J. Global Health Policy; 2020. The families first coronavirus response act: summary of key provisions.https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/the-families-first-coronavirus-response-act-summary-of-key-provisions/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Perry T., Abdallah I. Reuters; 2020. Coronavirus compounds Lebanon’s woes, many struggle for food.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-lebanon-poverty/coronavirus-compounds-lebanons-woes-many-struggle-for-food-idUSKBN21K1UN Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Holtmeier L., Alami M. Al Arabiya; 2020. Informal workers in Arab world hit hardest by coronavirus, unlikely to get help.https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2020/04/03/Informal-workers-in-Arab-world-hit-hardest-by-coronavirus-unlikely-to-get-help Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lewis L. Middle East Monitor; 2020. Can Lebanon afford a coronavirus shut-down?https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200318-can-lebanon-afford-a-coronavirus-shut-down/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chehayeb K. 2020. Twitter.https://twitter.com/chehayebk/status/1244385445708005377 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nizam D. 2020. Twitter.https://twitter.com/dod_nizam/status/1245647551505649665 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Abdul-Hamid H. World Bank Group; 2017. LEBANON: education public expenditure review.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/513651529680033141/pdf/127517-REVISED-Public-Expenditure-Review-Lebanon-2017-publish.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Houssari N. Arab News; 2020. Lebanon shuts schools after fourth coronavirus case.https://www.arabnews.com/node/1634941/middle-east Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lebanon . Human Rights Watch; 2020. Direct COVID-19 assistance to hardest hit - inadequate government response creates risk of hunger for many.https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/08/lebanon-direct-covid-19-assistance-hardest-hit Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen B., Cammett M. Informal politics and inequity of access to health care in Lebanon. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gunia A. Time; 2020. Why New Zealand’s Coronavirus Elimination Strategy Is Unlikely to Work in Most Other Places.https://time.com/5824042/new-zealand-coronavirus-elimination/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Newton K. RNZ; 2020. Covid-19 deadlier for Māori, Pasifika - modelling predicts.https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/414495/covid-19-deadlier-for-maori-pasifika-modelling-predicts Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sibley C.G., Harré N., Hoverd W.J., Houkamau C.A. The gap in the subjective wellbeing of Māori and New Zealand Europeans Widened between 2005 and 2009. Soc Indic Res. 2011;104(1):103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harris R., Tobias M., Jeffreys M., Waldegrave K., Karlsen S., Nazroo J. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in New Zealand: cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2006;367:2005–2009. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ahmed F., Ahmed N., Pissarides C., Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e240. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.COVID-19 and mitigating impact on health inequalities. Royal College of Physicians; 2020. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/covid-19-and-mitigating-impact-health-inequalities Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Binagwaho A., Ratnayake N. The role of social capital in successful adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gausman J., Austin S.B., Subramanian S.V., Langer A. Adversity, social capital, and mental distress among mothers of small children: a cross-sectional study in three low and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0228435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Agampodi T.C., Agampodi S.B., Glozier N., Siribaddana S. Measurement of social capital in relation to health in low and middle income countries (LMIC): a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Uphoff E.P., Pickett K.E., Cabieses B., Small N., Wright J. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cento Bull A., Jones B. Governance and Social Capital in Urban Regeneration: A Comparison between Bristol and Naples. Urban Stud. 2006;43:767–786. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Glynn J.R. Protecting workers aged 60–69 years from COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30311-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gerster J., Russell A. Global News; 2020. Fines, snitch lines: Crackdown on coronavirus rule breakers could have consequences.https://globalnews.ca/news/6859320/coronavirus-police-enforcement/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Denley R. 2020. City of Ottawa’s tough COVID-19 crackdown measures could backfire. Ottawa Citizen.https://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/denley-city-of-ottawas-tough-covid-19-crackdown-measures-could-backfire/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 119.McCutchan G., Wood F., Smits S., Edwards A., Brain K. Barriers to cancer symptom presentation among people from low socioeconomic groups: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1052. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3733-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nyqvist F., Victor C.R., Forsman A.K., Cattan M. The association between social capital and loneliness in different age groups: a population-based study in Western Finland. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:542. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3248-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Joint call for human rights oversight of government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. British Columbia Civil Liberties Association; 2020. https://bccla.org/our_work/joint-call-for-human-rights-oversight-of-government-responses-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Laskowski-Jones L. COVID-19 and changing social norms. Nursing. 2020;50(5):6. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000659348.89357.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Suspension of vaccination due to COVID-19 increases the risk of infectious diseases outbreaks - UNICEF and WHO. UNICEF; 2020. https://www.unicef.org/ukraine/en/press-releases/suspension-vaccination-due-covid-19-increases-risk-infectious-diseases-outbreaks Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 124.McGovern M.E., Canning D. Vaccination and all-cause child mortality from 1985 to 2011: global evidence from the demographic and health surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182:791–798. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nandi A., Shet A., Behrman J.R., Black M.M., Bloom D.E., Laxminarayan R. Anthropometric, cognitive, and schooling benefits of measles vaccination: Longitudinal cohort analysis in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam. Vaccine. 2019;37(31):4336–4343. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Consultation on ‘Strengthened EU cooperation against vaccine preventable diseases’ [Internet] EuroHealthNet; 2018. https://eurohealthnet.eu/sites/eurohealthnet.eu/files/publications/SUMMARY%20EuroHealthNet%20Vaccination%20Responses%202018.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Thomson K., Hillier-Brown F., Todd A., McNamara C., Huijts T., Bambra C. The effects of public health policies on health inequalities in high-income countries: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):869. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5677-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Adams J., Mytton O., White M., Monsivais P. Why are some population interventions for diet and obesity more equitable and effective than others? The role of individual agency. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gardner W., States D., Bagley N. The Coronavirus and the risks to the elderly in long-term care. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1750543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cacioppo J.T., Cacioppo S. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evid Based Nurs. 2014;17(2):59. doi: 10.1136/eb-2013-101379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Morrison J. The Guardian; 2018. Social isolation should be a public health priority.https://www.theguardian.com/social-care-network/2018/feb/23/social-isolation-public-health-priority Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nugent C. Letting young adults out first could be one option. Time; 2020. Governments are weighing how to ease Coronavirus lockdowns.https://time.com/5818593/young-people-leave-coronavirus-lockdown/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 133.ALONE launch a COVID-19 support line for older people Working in collaboration with the Department of Health and the HSE. ALONE; Dublin: 2020. https://alone.ie/alone-launch-a-covid-19-support-line-for-older-people-working-in-collaboration-with-the-department-of-health-and-the-hse/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kluge H.H.P. Statement presented at: WHO regional office for Europe. 2020. Older people are at highest risk from COVID-19, but all must act to prevent community spread.http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/statements/statement-older-people-are-at-highest-risk-from-covid-19,-but-all-must-act-to-prevent-community-spread Copenhagen. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Prisons worldwide risk becoming incubators of covid-19. The Economist; 2020. https://www.economist.com/international/2020/04/20/prisons-worldwide-risk-becoming-incubators-of-covid-19 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Limoncelli K.E., Mellow J., Na C. Determinants of intercountry prison incarceration rates and overcrowding in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int Crim Justice Rev. 2019;30:10–29. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hoge C.W., Reichler M.R., Dominguez E.A., Bremer J.C., Mastro T.D., Hendricks K.A. An epidemic of pneumococcal disease in an overcrowded, inadequately ventilated jail. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:643–648. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.De Claire K., Dixon L. The effects of prison visits from family members on prisoners’ well-being, prison rule breaking, and recidivism: a review of research since 1991. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;18:185–199. doi: 10.1177/1524838015603209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Winnick T.A., Bodkin M. Anticipated stigma and stigma management among those to be Labeled “ex-con. Deviant Behav. 2008;29(4):295–333. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Comninos A. 2020. COVID-19 in prison [Internet]. Association for the prevention of torture.https://apt.ch/en/blog/covid-19-in-prison/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Vandinther J. CTV News; 2020. COVID-19 pandemic taking harder toll on parents, families taking care of children living with autism.https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/covid-19-pandemic-taking-harder-toll-on-parents-families-taking-care-of-children-living-with-autism-1.4908808 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/disability/covid-19-disability-briefing.pdf?sfvrsn=fd77acb7_2&download=true Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Sanchack K.E., Thomas C.A. Autism spectrum disorder: primary care principles. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:972–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hill F. The Atlantic; 2020. The Pandemic is a crisis for students with special needs.https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2020/04/special-education-goes-remote-covid-19-pandemic/610231/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wentz B., Jaeger P.T., Lazar J. Retrofitting accessibility: the legal ineqality of after-the-fact online access for persons with disabilities in the United States. First Monday. 2011;16(11) https://firstmonday.org/article/view/3666/3077 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Employment and Social Development Canada . Government of Canada; 2020. Backgrounder: COVID-19 Disability Advisory Group.https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2020/04/backgrounder--covid-19-disability-advisory-group.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429–445. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Caryl F., Shortt N.K., Pearce J., Reid G., Mitchell R. Socioeconomic inequalities in children’s exposure to tobacco retailing based on individual-level GPS data in Scotland. Tob Control. 2019;29:367–373. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pearce N., Davey Smith G. Is social capital the key to inequalities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:122–129. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Sullivan W.F., Diepstra H., Heng J., Ally S., Bradley E., Casson I. Primary care of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(4):254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Macintyre S. Deprivation amplification revisited; or, is it always true that poorer places have poorer access to resources for healthy diets and physical activity? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Nogueira H.G. Deprivation amplification and health promoting resources in the context of a poor country. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1391–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Knottnerus J.A., Tugwell P. Methodological challenges in studying the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;121:A5–A7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Rychetnik L., Frommer M., Hawe P., Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(2):119–127. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M.C., Gray J.A.M., Haynes R.B., Richardson W.S. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Greenhalgh T., Schmid M.B., Czypionka T., Bassler D., Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Grierson J. The Guardian; 2020. Methadone to be supplied without new prescription during Covid-19 crisis Pharmacists will be allowed to give out medication to patients who have already been receiving it.https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/apr/08/methadone-to-be-handed-out-without-prescription-during-covid-19-crisis Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 159.UPDATE: Halt on French local authority’s alcohol ban during lockdown. The Local; 2020. https://www.thelocal.fr/20200324/french-local-authority-bans-sale-of-alcohol-during-lockdown Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 160.McElroy D. N Opinion; 2020. Sweden is making a dangerous bet on a “cultural cure” to COVID-19.https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/sweden-is-making-a-dangerous-bet-on-a-cultural-cure-to-covid-19-1.1001557 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Muller S. 2020. Spain discusses basic income for the poorest amid coronavirus fallout. DW.https://www.dw.com/en/spain-discusses-basic-income-for-the-poorest-amid-coronavirus-fallout/a-53096390 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 162.Ford L. The Guardian; 2020. “Calamitous”: domestic violence set to soar by 20% during global lockdown.https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/28/calamitous-domestic-violence-set-to-soar-by-20-during-global-lockdown-coronavirus reproductive rights (developing countries). Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Ellis C. Open Democracy; 2020. COVID-19: Canada locks its gates to asylum seekers: for asylum seekers, the route to a safe home is being all but eliminated.https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/pandemic-border/covid-19-canada-locks-its-gates-asylum-seekers/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 164.Makinen M., Waters H., Rauch M., Almagambetova N., Bitran R., Gilson L. Inequalities in health care use and expenditures: empirical data from eight developing countries and countries in transition. WHO Bull. 2000;78(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.CSDH . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Abdalla S., Galea S. Think Global Health; 2020. Africa and Coronavirus - Will Lockdowns Work?https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/africa-and-coronavirus-will-lockdowns-work Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 167.Craig P., Di Ruggiero E., Frohlich K.L., Mykhalovskiy E., White M. NIHR Journals Library; Southampton, UK: 2018. Taking account of context in population health intervention research: guidance for producers, users and funders of research.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK498645/ Available at. [Google Scholar]