Abstract

Some individuals are more psychologically resilient to adversity than others, an issue of great importance during the emerging mental health issues associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. To identify factors that may contribute to greater psychological resilience during the first weeks of the nation-wide lockdown efforts, we asked 1,004 U.S. adults to complete assessments of resilience, mental health, and daily behaviors and relationships. Average resilience was lower than published norms, but was greater among those who tended to get outside more often, exercise more, perceive more social support from family, friends, and significant others, sleep better, and pray more often. Psychological resilience in the face of the pandemic is related to modifiable factors.

Dear editor,

During recent months, the COVID-19 pandemic has upended normal existence for much of the world's population including the United States. The resulting social isolation and economic uncertainty have led to significant increases in mental health concerns, including loneliness, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Killgore et al., 2020), however, people differ widely in how they respond to challenges and difficulties. The ability to withstand setbacks, adapt positively, and bounce back from adversity is described as “resilience” (Luthar and Cicchetti, 2001). We wanted to identify key behaviors and other factors that may contribute to psychological resilience during the pandemic period. Here, we focused on resilience as the self-perceived trait-like ability to cope in the face of adversity, as measured by the Connor-Davidson Risk Scale (CD-RISC) (Connor and Davidson, 2003).

During the third week of the COVID-19 stay-at-home guidance in the United States (i.e., April 9–10, 2020), we collected online questionnaires from 1,004 English speaking participants in all 50 states (18–35 years; 562 females). Participants completed the CD-RISC, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (Beck et al., 1996), the Zung Self-Rated Anxiety Scale (SAS) (Zung, 1971), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988) and questions about sleep, emotional state, exercise, and daily activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, during the first weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown in the United States, we found that psychological resilience among those sampled was significantly lower for the CD-RISC (M = 66.84, SD=17.48; t (1579)=16.29, p<.00001) compared to published normative data for this scale (Connor and Davidson, 2003). This suggests that the level of self-perceived psychological resilience among the U.S. populace may have been adversely affected by the ongoing crisis, perhaps through acute changes in emotional outlook or perceived support. Psychological resilience is vital for the ability to cope effectively with hardship, uncertainty, and change. This was clear in our sample, as lower scores on the CD-RISC were unambiguously associated with worse mental health outcomes, including more severe depression (r = −0.55, p<.00001) and suicidal ideation (r = −0.38, p<.00001) scores on the BDI, and more severe anxiety scores on the SAS (r = −0.42, p<.00001). Lower resilience was also associated with greater worry about the effects of COVID-19, including higher scores on several 7-point Likert scales assessing concerns such as: “I fear we will never be free of COVID-19” (r = −0.17, p<.00001), “since the outbreak, I feel scared about the future” (r = −0.31, p<.00001), “I have a persistent deep sense of dread from this crisis” (r = −0.29, p<.00001), and “I worry about how this crisis is affecting my mental health” (r = −0.33, p<.00001) as examples. Those with lower resilience expressed greater difficulty coping with the emotional challenges of the pandemic crisis.

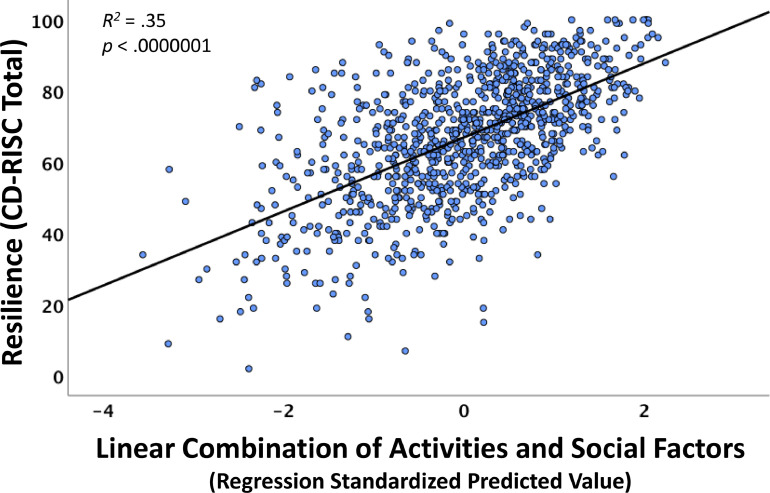

Owing to the fundamental role of resilience in sustaining mental health, we sought to identify common social factors and daily activities that predicted greater resilience during the lockdown. Multiple linear regression with stepwise entry and deletion demonstrated that greater resilience was predicted by a linear combination of several variables (adjusted R 2 = 0.350, F 7,971=76.19, p<.00001) including: more days per week spent outside in the sunshine for at least 10 min (β =0.07, p=.012), more minutes of daily exercise (β =0.09, p=.0004), greater perceived family support (β =0.14, p<.0001), more perceived social support from friends (β =0.17, p<.00001), lower severity of insomnia (β = −0.18, p<.00001), greater perceived care and support from a close significant other (β =0.18, p<.00001), and greater frequency of prayer (β =0.23, p<.00001). As shown in Fig. 1 , those who scored higher on this combination of factors also tended to show greater resilience during the lockdown.

Fig. 1.

Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown was predicted by a linear combination of daily activities and social support. The x-axis reflects each individual's standardized predicted value from the seven combined resilience items. The y-axis reflects the score on the CD-RISC.

Of course, these associations need to be considered in light of the cross-sectional nature of the data and the restricted age range, which potentially limits the generalizability of the findings to older groups or those whose life circumstances may differ from this sample. Nonetheless, bolstering psychological resilience should be a primary public health emphasis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social support from family, friends, and a special caring loved one were each independently associated with greater resilience in our sample. During periods of shelter-in-place orders, it is important to foster these relationships and to find creative ways to stay emotionally connected with those we care about. Daily activities are also important. Exposure to the outdoors and sunlight for a few minutes each day and getting a bit more exercise were both also associated with greater resilience. Finally, spiritual health is another facet of well-being to consider, as more frequent prayer was independently associated with greater resilience in our sample. We find that those who actively engaged in these vital activities and nurtured their relationships tended to be the most resilient to the challenges to mental health imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

None.

Declaration of Competing Interests

None.

References

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Brown G.K. 2nd ed. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Connor K.M., Davidson J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D., Cloonan S.A., Taylor E.C., Dailey N.S. Loneliness: a signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S.S., Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001;12(4):857–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G.D., Dahlem N.W., Zimet S.G., Farley G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung W.W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]