Abstract

Background

Amid growing antimicrobial resistance, there is an increasing focus on antibiotic stewardship efforts to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. In this context, novel approaches for treating infections without antibiotics are being explored. One such strategy is the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs). Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the rates of symptom resolution and infectious complications in adult women with uncomplicated UTIs treated with antibiotics versus NSAIDs.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, CINHAL, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, EMBASE, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception until January 13, 2020, for randomized controlled trials comparing NSAIDs with antibiotics for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs in adult women. Studies comparing symptom resolution between groups were eligible. Two authors screened all studies independently and in duplicate; data were abstracted using a standardized template. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool.

Results

Five randomized trials that included 1309 women with uncomplicated UTI met inclusion criteria. Three studies (1130 patients) favored antibiotic therapy in terms of symptom resolution. Two studies (179 patients) found no difference between NSAIDs and antibiotics in terms of symptom resolution. Three studies reported rates of pyelonephritis, two of which found higher rates in patients treated with NSAIDs versus antibiotics. Between two studies that reported this outcome (747 patients), patients randomized to NSAIDs received fewer antibiotic prescriptions compared with those in the antibiotics group. Three studies were at low risk of bias, one had an unclear risk of bias, and one was at high risk of bias.

Discussion

For the outcomes of symptom resolution and complications in adult women with UTI, evidence favors antibiotics over NSAIDs.

Prospero

CRD42018114133

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-05745-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: urinary tract infection, systematic review, NSAIDs, antibiotics, antibiotic stewardship

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common, ranking as the second most frequent indication for antibiotic prescribing in the outpatient setting.1, 2 The majority of UTIs are “uncomplicated,” occurring in non-pregnant adult women who are not immunocompromised and have normal genitourinary structure and function.3 Each year, 12.6% of women will have a UTI, and half of all women will have at least one UTI by age 32.4 The standard of care for uncomplicated UTI is oral antibiotic therapy, which typically leads to rapid symptom resolution and reduces the risk of complications such as pyelonephritis.5

In recent years, growing antibiotic resistance has led to efforts to use antibiotics more judiciously. Specifically for uncomplicated UTIs, these initiatives have sought to reduce the amount—either duration or frequency—and spectrum of antibiotics.6–8 Interviews with women indicate willingness to delay or avoid antibiotic prescriptions when safe to do so.9, 10 Furthermore, some UTIs are self-limited without treatment and thus may not require antibiotic therapy.11 For example, a randomized controlled trial comparing nitrofurantoin with placebo for uncomplicated UTI demonstrated spontaneous symptomatic cure or improvement in over half of participants receiving placebo who had UTIs as proven by a combination of symptoms/signs and positive laboratory testing.12 While a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found placebo to be inferior to antibiotics for resolution of UTI symptoms,13 it is unclear whether non-antibiotic treatment regimens for uncomplicated UTIs may be feasible as an outpatient antibiotic stewardship strategy. For example, cranberry extract was initially considered a potential antibiotic-sparing option; however, subsequent research has not supported its use in the treatment of UTI over antibiotics.14

One potential antibiotic-sparing treatment for UTI is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) which potentially provides relief from dysuria related to elevated prostaglandin E2 levels.15, 16 Targeting symptom relief is particularly attractive as dysuria, frequency, and urgency may be misattributed to UTI when in fact no infection is present (e.g., “urethral syndrome”).17 Furthermore, though evidence is mixed, NSAIDs may also have direct antimicrobial properties.18–21 Within this context, Bleidorn and colleagues demonstrated in a 2010 randomized pilot study that NSAIDs were non-inferior for improving symptoms as well as preventing relapse and non-serious adverse events when compared with antibiotics for uncomplicated UTI.22 Conversely, in 2015, Gágyor and colleagues found treatment with NSAIDs to be less effective compared with treatment with antibiotics for symptom relief and to result in more cases of pyelonephritis.23 Similarly, evidence has been mixed for using NSAIDs for UTI in other contexts. While NSAIDs may be less effective than antibiotics for inpatient UTI,24 there is a potential role for NSAID therapy as part of antibiotic stewardship efforts that include delayed antibiotic prescriptions.25

To better understand whether NSAIDs may help in management of UTI and reduce overall antibiotic prescribing, we performed a systematic review of randomized controlled trials to determine the effect of treatment with NSAIDs versus antibiotics for uncomplicated UTI on symptom resolution, development of infectious complications, and antibiotic prescribing frequency.

METHODS

We published a protocol (PROSPERO CRD42018114133) and followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) recommendations in the conduct of this systematic review.26

Data Sources and Searches

A medical librarian (WT) performed literature searches in the following databases from their inception through January 13, 2020: PubMed, CINHAL (EBSCO), Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, EMBASE (Embase.com), and ClinicalTrials.gov. Searches for each database included appropriate controlled vocabulary terms when available, combined with keywords such as “UTIs,” “Analgesics,” and “Antibiotics” (Appendix). No search restrictions were placed on publication date, language, or completion status. To ensure inclusion of clinical trials that may have been completed but not yet published, we reviewed the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials website as well. We also performed hand-searched of bibliographies to ensure inclusion of all relevant articles.

Study Selection

Randomized controlled trials were eligible for inclusion if they compared antibiotics versus NSAIDs for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs. Uncomplicated UTIs were defined as UTIs (diagnosed based on symptoms of urgency, dysuria, frequency, or suprapubic tenderness, with or without dipstick or culture evidence of bacteriuria) in non-pregnant adult women who were not immunocompromised and had no prior urological procedures or hardware. “Adult” was defined as 18 years of age or older for studies conducted in countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). For studies conducted in other countries, a lower age limit of 15 years of age was used after discussion among two authors (MRC, PKP). Two authors (MRC, PKP) independently determined study eligibility. A third author (VV) resolved any differences of opinion between the two primary reviewers. Interrater agreement for study eligibility was assessed using Cohen’s kappa.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data were extracted from the included studies by one author (MRC) and verified by another (PKP) using a standardized template. Data extracted included the number and type of patients, definitions of UTI, and outcome measures (time to symptom resolution, number of antibiotic prescriptions, cases of pyelonephritis).

Two authors (MRC and PKP) independently assessed the risk of bias in included trials using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool.27 Studies were only defined as “low risk” if they met the criteria for low risk of bias for all six domains. Studies with missing methodological data were considered to be at unclear risk of bias.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The primary outcome of interest was the proportion of individuals with resolution of symptoms by day 3 or day 4 post-randomization. In accordance with existing studies, we chose 30 days post-randomization for assessment of secondary outcomes that included (a) incidence of pyelonephritis and (b) number of antibiotic prescriptions. For all outcomes, we reported the difference in risk with 95% confidence intervals. When data regarding symptom resolution in both groups were available, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) with antibiotics versus NSAIDs to achieve symptom resolution by day 3 or 4 post-randomization in one additional person as the reciprocal of the difference in risk, or 1/(absolute risk reduction). Because of clinical heterogeneity in antibiotic exposure, NSAID selection, and outcomes reported in included studies, we did not conduct formal meta-analyses.

RESULTS

Search Results and Study Details

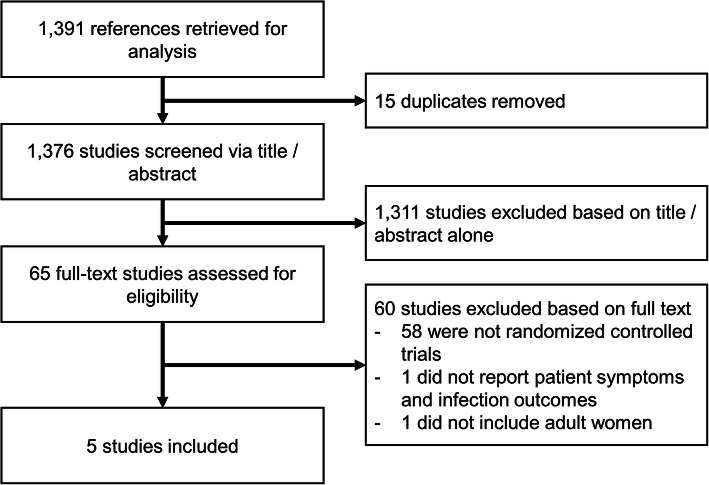

A total of 1391 citations were retrieved by our search, including 15 duplicates removed prior to screening. Of these, 65 full-text studies were eligible for inclusion following title and abstract review and 5 randomized clinical trials were included (Fig. 1). Interrater agreement for study inclusion was excellent at 0.97. Four studies were conducted in Europe, and one was conducted in Pakistan.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Characteristics of Included Patients

Four studies22, 23, 28, 29 included adult women over the age of 18 while one study30 included women over the age of 15. Upper age limits ranged from 50 to 70 years, with one study22 having no upper age limit (Table 1). UTIs were generally defined as a constellation of typical symptoms (i.e., dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic/lower abdominal pain). One study28 included individuals with self-diagnosed symptomatic cystitis if they had urine dipstick results positive for nitrites, leukocyte esterase, or both. Four studies22, 23, 28, 29 excluded patients with upper UTI signs (i.e., fever and back pain), pregnancy, diabetes, prior urological interventions, immunosuppressive states, urinary catheterization, recent UTI, current antibiotic or NSAID use, or contraindications to study drugs. Four studies22, 23, 28, 29 included baseline urine culture results at the time of inclusion, though culture results were not used as eligibility criteria (Table 1). The share of patients with positive urine cultures at the time of inclusion ranged from 67 to 86% in the NSAID groups and 64 to 80% in the antibiotic groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Randomized Controlled Trials

| Study, year | Country | Publication status | Patients, n | Definition of UTI | Patients with positive urine cultures, n (%)* | Gender and age criteria | Follow-up period, days | Medication regimen | Risk of bias† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSAID | Antibiotic | NSAID | Antibiotic | NSAID | Antibiotic | |||||||

| Bleidorn et al., 2010 | Germany | Full text | 40 | 39 | Typical symptoms of a UTI (dysuria and/or frequency) | 31 (86) | 24 (80) | Women > 18 years | 28 | Ibuprofen 400 mg 3 × per day for 3 days | Ciprofloxacin 250 mg 2 × per day (+ 1 placebo) for 3 days | Unclear |

| Gágyor et al., 2015 | Germany | Full text | 248 | 246 | Dysuria and/or frequency/urgency of micturition, with or without lower abdominal pain | 179 (76) | 181 (77) | Women 18–65 years | 28 | Ibuprofen 400 mg 3x per day for 3 days plus 1 sachet placebo granules | Fosfomycin-trometamol 3 g sachet × 1 plus placebo tablets 3 × per day for 3 days | Low |

| Jamil et al., 2016 | Pakistan | Full text | 50 | 50 | Symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, and suprapubic pain associated with UTI | NR | NR | Women 15–50 years | 5 | Potassium citrate 2 × per day + Flurbiprofen 100 mg 2 × per day for 5 days | Ciprofloxacin 250 mg 2 × per day for 5 days | High |

| Kronenberg et al., 2017 | Switzerland | Full text | 133 | 120 | One or more symptoms of typical lower UTI (dysuria, frequency, macrohematuria, cloudy or smelly urine) or self-diagnosed symptomatic cystitis if urine dipstick positive for nitrites, leukocytes, or both | 96 (72) | 89 (74) | Women 18–70 years | 30 | Diclofenac 75 mg 2 × per day for 3 days | Norfloxacin 400 mg 2 × per day for 3 days | Low |

| Vik et al., 2018 | Norway, Denmark, and Sweden | Full text | 194 | 189 | Dysuria combined with either increased urinary frequency or urgency or both, with or without visible hematuria | 121 (67) | 113 (64) | Women 18–60 years | 28 | Ibuprofen 600 mg 3 × per day for 3 days | Pivmecillinam 200 mg 3 × per day for 5 days | Low |

NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UTI, urinary tract infection; NR; not reported

*Percentage of patients with a “positive culture” at the time of enrollment of those with reported urine culture results. The cutoff for identifying “positive cultures” varied between studies from ≥ 102 colony forming units/mL to ≥ 105 colony forming units/mL

†Assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool

Study Medications

All studies compared the use of NSAIDs with antibiotic therapy for the treatment of uncomplicated UTIs (Table 1). One study30 used potassium citrate in addition to NSAID therapy in the treatment arm. The NSAID was ibuprofen in three trials,22, 23, 29 flurbiprofen in one trial,30 and diclofenac in one trial.28 Antibiotic therapy also varied across studies with two studies22, 30 using ciprofloxacin, one study23 using fosfomycin-trometamol, one study28 using norfloxacin, and one study29 using pivmecillinam.

Symptom Resolution Outcomes

Though all studies included symptom resolution as a primary outcome, the method of assessment differed (Table 2). Symptom resolution was assessed as follows: percent of patients with symptom resolution on day 3 (one study28); percent of patients with symptom resolution on day 4 (two studies22, 29); symptom burden on days 0–7 measured as area under the curve of the sum of daily symptom scores (one study23); and comparison of pre- and post-treatment symptom scores on day 5 (one study30). For these endpoints, two studies tested for non-inferiority only, using non-inferiority margins of 10%23 and 25%,29 one tested for non-inferiority (using a 15% non-inferiority margin) and superiority,28 and two tested for differences between the two groups22, 30. The results for these primary outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes of Included Randomized Controlled Trials

| Study, year | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Findings | ||

| Bleidorn et al., 2010 | Symptom resolution by day 4 (test for difference) | No significant difference between NSAIDs and antibiotics in achieving symptom resolution by day 4 | Burden of symptoms, frequency of relapses, secondary antibiotic treatments, incidence of adverse events |

| Gágyor et al., 2015 | Burden of symptoms on days 0–7, measured as AUC of the sums of daily symptom scores (test for non-inferiority); number of courses of antibiotics on days 0–28 (test for superiority) | NSAIDs inferior to antibiotics in achieving symptom resolution as measured by the ratio of the AUC of the sum of symptom scores on days 0–7 for both groups | Number of adverse events (including pyelonephritis), frequency of relapses, symptom burden, number of antibiotic doses per patient |

| Jamil et al., 2016 | Comparison of post-treatment total symptom scores on day 5 (test for difference) | No significant difference between symptom scores on day 5 for NSAID and antibiotic groups | Comparison of scores for specific symptoms (frequency, urgency, dysuria, suprapubic pain) |

| Kronenberg et al., 2017 | Symptom resolution by day 3 (test for non-inferiority and superiority) | NSAIDs inferior to antibiotics in achieving symptom resolution and antibiotics superior to NSAIDs in achieving symptom resolution by day 3 | Use of antibiotics up to day 30, re-consultation for UTIs, mean composite symptom scores, adverse events (including pyelonephritis), time to resolution of symptoms, working days lost, satisfaction with management |

| Vik et al., 2018 | Symptom resolution by day 4 (test for non-inferiority) | NSAIDs inferior to antibiotics in achieving symptom resolution by day 4 | Duration of symptoms and symptom load; proportion of patients with a positive second urine culture, in need of a medical consult for UTI within 4 weeks, and who received antibiotics during the study period; frequency of adverse events (including pyelonephritis) |

NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UTI, urinary tract infection; AUC, area under the curve

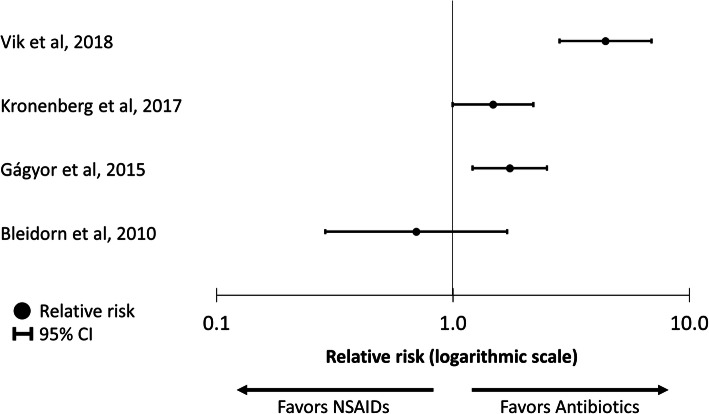

Of the studies reporting symptom resolution by day 3 or 4 post-randomization (all low risk of bias), one smaller study22 (79 patients) demonstrated no significant difference between NSAIDs and antibiotics for symptom resolution (58% of patients treated with NSAIDs had symptoms resolution at 3 days versus 52% of those treated with antibiotics, p = 0.744 for difference). Three larger studies23, 28, 29 (1130 total patients) demonstrated higher rates of symptom resolution in the antibiotic groups, with symptom resolution 17 to 35 percentage points higher in the antibiotic group compared with the NSAID group (Table 3; Fig. 2). One study30 (high risk of bias) compared symptom scores at the end of the trial, day 5 post-randomization, and found no significant difference in scores between the NSAID and antibiotic groups (1.4 versus 1.9; p = 0.13 for difference). Table 4 shows the NNT with antibiotics to achieve symptom resolution in one additional patient by days 3 to 4 post-randomization, which range from 3.029 to 6.4.23

Table 3.

Summary of Reported Outcomes in Randomized Controlled Trials Assessing NSAIDs Versus Antibiotics for Women with Uncomplicated UTIs

| Patients, n | Patients with symptom resolution by day 3 or 4, n (%) | Mean of post-treatment total symptom score on day 5* | Women receiving antibiotics for any reason during study period, n (%) | Patients with pyelonephritis during the study period, n (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, year | NSAID | Antibiotic | NSAID | Antibiotic | Risk difference (95% CI)† | NSAID | Antibiotic | p value | NSAID | Antibiotic | Risk difference (95% CI)‡ | NSAID | Antibiotic | Risk difference (95% CI)§ |

| Bleidorn et al., 2010 | 40 | 39 | 21 (58)| | 17 (52)| | 9 (− 13 to 31)| | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gágyor et al., 2015 | 248 | 246 | 91 (39)| | 129 (56)| | 17 (9 to 26)| | NR | NR | NR | 85 (35) | 243 (100) | − 65 (− 71 to − 59) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 1.7 (− 0.3 to 3.6) |

| Jamil et al., 2016 | 50 | 50 | NR | NR | NR | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.13 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kronenberg et al., 2017 | 133 | 120 | 72 (54)¶ | 96 (80)¶ | 27 (15 to 38)¶ | NR | NR | NR | 82 (62) | 118 (98) | − 37 (− 46 to − 28) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (1 to 8) |

| Vik et al., 2018 | 194 | 189 | 70 (39)| | 131 (74)| | 35 (27 to 43)| | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (1 to 8) |

UTI, urinary tract infection; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NR, not reported

*Total symptom score is the sum of symptom scores for urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, and pain

†Positive numbers indicate higher rates of symptom resolution among patients receiving antibiotics compared with those receiving NSAIDS

‡Positive numbers indicate higher rates of antibiotic use in the NSAID group

§Positive numbers indicate higher rates of pyelonephritis in the NSAID group

|Symptom resolution by day 4

¶Symptom resolution by day 3

Fig. 2.

Comparison of relative risk of symptom resolution by day 4 post-randomization for patients treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus antibiotics.

Table 4.

Number Needed to Treat with Antibiotics Rather than Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) to Achieve Symptom Resolution in One Additional Person by Day 3 or 4 or Prevent One Additional Case of Pyelonephritis by Day 28 to 30

| Study* | NNT to achieve symptom resolution in one additional patient by day 3 or 4† | NNT to prevent one additional case of pyelonephritis by days 28 to 30‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Gágyor et al., 2015 | 6.4 | 62.1 |

| Kronenberg et al., 2017 | 3.9 | 22.2 |

| Vik et al., 2018 | 3.0 | 27.7 |

NNT, number needed to treat

*Bleidorn et al. (2010)22 was not included as it demonstrated higher symptom resolution in the NSAID group compared with the antibiotic group and did not report subsequent cases of pyelonephritis. Jamil et al. (2016)30 was not included as it did not report the number of individuals with symptom resolution by day 3 or 4 and did not report subsequent cases of pyelonephritis

†Number needed to treat to achieve additional symptom resolution calculated for three trials that included symptom resolution by day 3 or 4 as a primary or secondary outcome and there was a statistically significant difference in symptom resolution between the NSAID and antibiotic groups

‡Number needed to treat to prevent one additional case of pyelonephritis calculated for three trials that reported incidence of pyelonephritis in the study period

Secondary Outcomes

Two studies23, 28 reported the proportion of participants that received antibiotics for any reason during the study period—both studies reported fewer antibiotic prescriptions in the NSAID versus antibiotic groups (Table 3). Three studies23, 28, 29 reported rates of pyelonephritis during the trial period. Among these, pyelonephritis was uncommon, occurring in fewer than 5% of patients in any arm. Two studies found patients who received antibiotics had lower rates of pyelonephritis compared with those who received NSAIDs. Table 4 shows the number of individuals who would need to be treated with antibiotics over NSAIDs to avoid one case of pyelonephritis.

Risk of Bias

Three of the studies were found to have a low risk of bias, one was found to have an unclear risk of bias, and one was found to have a high risk of bias (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we evaluated five randomized controlled trials (of 1309 patients) comparing NSAIDs with antibiotics for treatment of uncomplicated UTI. Although study protocols and reported outcomes were heterogeneous, two smaller studies that were at high and unclear risk of bias found no difference between NSAIDs and antibiotics, while three studies with low risk of bias supported antibiotic therapy over NSAIDs in terms of symptom resolution. Furthermore, two studies at low risk of bias found higher risks of pyelonephritis in patients who received NSAIDs versus antibiotics; the third study with low risk of bias also found a higher risk of pyelonephritis in patients receiving NSAIDs, but the confidence interval for the risk difference included zero. In sum, these findings support the use of antibiotics as first-line treatment for uncomplicated UTI for both symptom resolution and prevention of pyelonephritis.

Despite the superiority of antibiotic therapy, 39–58% of participants in the NSAID groups achieved symptom resolution by day 3 or 4.22, 23, 28, 29 For comparison, a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials demonstrated clinical success (symptom improvement or resolution by first follow-up visit) in 25–54% of participants in the placebo arms.13, 25 One possible explanation for why many UTI symptoms resolved without antibiotic therapy is that not all women included in the studies may have had true UTIs. Inclusion in most studies was based on symptoms alone—a commonly accepted approach for uncomplicated UTIs31 that is consistent with several clinical practice guidelines from countries where the trials were conducted.32–34 However, clinical symptoms only correctly diagnose UTIs half of the time.31, 35 Thus, it is possible that a large number of participants may not have had a UTI or been at risk of worsening infection. Indeed, in the four studies that collected urine specimens for culture at the time of inclusion, only 64–86% of patients in either study arm had positive cultures.22, 23, 28, 29 Women often suffer from urinary symptoms for a host of reasons (e.g., incontinence, medication side effects) that are misdiagnosed as a UTI.36 Barriers to obtaining timely urine testing often promote alternatives to testing, such as “as needed” antibiotic prescriptions or prescriptions by phone.37

Furthermore, even patients with “positive” urine cultures may have asymptomatic bacteriuria and thus not require treatment. Misdiagnosis of UTI is particularly common in elderly women who have other long-standing urinary tract symptoms, such as incontinence.38–40 However, the maximum age cutoffs used in four out of five studies (50 to 70 years of age) likely avoided some challenges of diagnosing UTIs in the elderly—while also limiting generalizability to these groups. In summary, although there is a subset of individuals who clearly benefit from antibiotics, there is likely another segment that does not benefit from antibiotics and could be appropriately treated with NSAIDs or no therapy.

Another important finding from the included studies was that only 2.0–4.5% of individuals treated with NSAIDs subsequently developed pyelonephritis (based on 3 studies with 1130 patients).23, 28, 29 Thus, to avoid one case of pyelonephritis, 22 to 62 people would need to be treated with antibiotics. Notably, these reported rates of pyelonephritis in NSAID groups were higher than placebo arms of prior clinical trials (0.4%41 and 2.6%12). While better follow-up to assess outcomes in the NSAID studies may be partially responsible, NSAIDs have also been associated with worse outcomes in other infections, such as community-acquired pneumonia,42, 43 possibly due to immune suppresion.44 These and other potential adverse effects of NSAIDs must be better understood before these drugs can be used for uncomplicated UTI.

In summary, this review demonstrates the superiority of antibiotics over NSAIDs for the treatment of uncomplicated UTIs. However, future research should focus on better diagnosing UTI and stratifying women with uncomplicated UTIs to identify the subset that would benefit from antibiotic treatment while avoiding unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. Other potential antibiotic-sparing strategies should be further explored as well, including delayed antibiotic prescriptions for lingering symptoms only,37 point-of-care testing–driven prescribing algorithms,45 and provider audit reports and reminders.46 Given the high incidence of uncomplicated UTIs (and likely misdiagnosed UTIs) as well as the number of antibiotic prescriptions written for these infections,1, 2, 4, 47 elimination of even a quarter of antibiotic prescriptions for uncomplicated UTIs would result in tens of thousands fewer antibiotic courses per year. Such a shift in practice patterns could have significant downstream ramifications, including reducing the number of adverse drug reactions, Clostridium difficile infections, and multi-drug resistant organisms.48

This review has several strengths, including a comprehensive literature search that included multiple databases without language filters as well as a published protocol. It also has several limitations. We could not perform a meta-analysis given substantial heterogeneity in treatment across studies. Second, there was substantial variability in reported outcomes. Third, only five trials met inclusion criteria, limiting the ability to detect rare outcomes. Fourth, the follow-up period for all studies was 1 month or less, preventing the assessment of long-term impact of NSAID versus antibiotic therapy on patient outcomes, though a follow-up study to one trial demonstrated no impact on recurrent UTI or pyelonephritis from 28 days to 6 months post-randomization.49

CONCLUSION

This review adds two important pieces of information to what is currently known about UTI. First, it confirms the role of antibiotics as first-line treatment for uncomplicated UTIs compared with symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs. Second, it demonstrates that about half of patients experience symptom resolution with NSAIDs alone, indicating a potential target to reduce antibiotic prescriptions. While fewer than 5% of those using NSAIDs developed pyelonephritis, the potential adverse effects of NSAIDs as treatment need to be considered. Taken together, these data point to the importance of future research to identify patients who would most benefit from antibiotic therapy so that prescribing can be targeted towards those individuals while avoiding prescribing to those who would not derive incremental benefit. Such an approach would ensure women have adequate, prompt symptom resolution while at the same time avoiding unnecessary antibiotic prescribing—the kind of “win-win” that is the ultimate goal of antibiotic stewardship efforts.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 63 kb)

(DOCX 29 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This review of published literature did not include identifiable private information and thus did not require review by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Matthew R. Carey, Email: mrcarey@med.umich.edu.

Payal K. Patel, Email: payalkp@med.umich.edu.

References

- 1.Lundborg CS, Olsson E, Molstad S. Antibiotic prescribing in outpatients: a 1-week diagnosis-prescribing study in 5 counties in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(6):442–8. doi: 10.1080/00365540110080647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen I, Hayward AC. Antibacterial prescribing in primary care. J Antibicrob Chemother. 2007;60(Suppl 1):i43–47. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolle LE. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foxman B, Brown P. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: transmission and risk factors, incidence, and costs. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17(2):227–41. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooton TM. Clinical practice: uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1028–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1104429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed October 5, 2019.

- 7.Antibiotic / Antimicrobial Resistance 2017. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html. Published 2017. Accessed July 2, 2019.

- 8.Butler CC, Dunstan F, Heginbothom M, et al. Containing antibiotic resistance: decreased antibiotic-resistant coliform urinary tract infections with reduction in antibiotic prescribing by general practices. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:785–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leydon GM, Turner S, Smith H, et al. Women’s views about management and cause of urinary tract infection: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2010;340:c279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, Moll van Charante EP, et al. Women with symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection are often willing to delay antibiotic treatment: a prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7(12):653–60. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christiaens TC, De Meyere M, Verschraegen G, et al. Randomised controlled trial of nitrofurantoin versus placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adult women. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:729–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falagas ME, Kotsantis IK, Vouloumanou EK, et al. Antibiotics versus placebo in the treatment of women with uncomplicated cystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Infect. 2009;58:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guay DR. Cranberry and urinary tract infections. Drugs. 2009;69:775–807. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farkas A, Alajem D, Dekel S, et al. Urinary prostaglandin E2 in acute bacterial cystitis. J Urol. 1980;124(4):455–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheeler MA, Hausladen DA, Yoon JH, et al. Prostaglandin E2 production and cyclooxygenase-2 induction in human urinary tract infections and bladder cancer. J Urol. 2002;168(4 Pt 1):1568–73. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little P, Merriman R, Turner S, et al. Presentation, pattern, and natural course of severe symptoms, and role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among patients presenting with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2010;340:b5633. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elvers KT, Wright SJ. Antibacterial activity of the anti-inflammatory compound ibuprofen. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;20(2):82–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obad J, Suskovic J, Kos B. Antimicrobial activity of ibuprofen: new perspectives on an “Old” non-antibiotic drug. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2015;71:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah PN, Marshall-Batty KR, Smolen JA, et al. Antimicrobial activity of ibuprofen against cystic fibrosis-associated gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62(3). 10.1128/AAC.01574-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Whiteside SA, Dave S, Reid G, et al. Ibuprofen lacks direct antimicrobial properties for the treatment of urinary tract infection isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2019;68(8):1244–52. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bleidorn J, Gágyor I, Kochen MM, et al. Symptomatic treatment (ibuprofen) or antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) for uncomplicated urinary tract infection?--results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Med. 2010;8:30. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gágyor I, Bleidorn J, Kochen MM, et al. Ibuprofen versus fosfomycin for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h6544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aloush SM, Al-Awamreh K, Abu Sumaqa Y, et al. Effectiveness of antibiotics versus ibuprofen in relieving symptoms of nosocomial urinary tract infection: a comparative study. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2019;31(1):60–64. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore M, Trill J, Simpson C, et al. Uva-ursi extract and ibuprofen as alternative treatments for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women (ATAFUTI): a factorial randomized trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(8):973–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from https://www.handbook.cochrane.org.

- 28.Kronenberg A, Butikofer L, Odutayo A, et al. Symptomatic treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in the ambulatory setting: randomised, double blind trial. BMJ. 2017;359:j4784. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vik I, Bollestad M, Grude N, et al. Ibuprofen versus pivmecillinam for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamil MN, Farooq U, Sultan B, et al. Role of symptomatic treatment in comparison to antibiotics in uncomplicated urinary tract infections. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2016;28:734–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson ML, Gaido L. Laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infections in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(8):1150–8. doi: 10.1086/383029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kranz J, Schmidt S, Lebert C, et al. Uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired urinary tract infection in adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(50):866–73. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flottorp S, Oxman AD, Cooper JG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute urinary tract problems in women. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke. 2000;120(15):1748–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 88, 2012.

- 35.Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL, et al. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2002;287:2701–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cox L, Rovner ES. Lower urinary tract symptoms in women: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Opin Urol. 2016;26:328–33. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:90–6. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petty LA, Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, et al. Risk factors and outcomes associated with treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(11):1519–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Ferry SA, Holm SE, Stenlund H, et al. Clinical and bacteriological outcome of different doses and duration of pivmecillinam compared with placebo therapy of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women: the LUTIW project. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25(1):49–57. doi: 10.1080/02813430601183074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basille D, Plouvier N, Trouve C, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may worsen the course of community-acquired pneumonia: a cohort study. Lung. 2017;195(2):201–08. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9973-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voiriot G, Dury S, Parrot A, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs may affect the presentation and course of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2011;139(2):387–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bancos S, Bernard MP, Topham DJ, et al. Ibuprofen and other widely used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit antibody production in human cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;258(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, et al. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–73. doi: 10.3310/hta13190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vellinga A, Galvin S, Duane S, et al. Intervention to improve the quality of antimicrobial prescribing for urinary tract infection: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ. 2016;188:108–15. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med. 2002;113(Suppl 1A):5s–13s. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright J, Paauw DS. Complications of antibiotic therapy. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97(4):667–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bleidorn J, Hummers-Pradier E, Schmiemann G, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infections and complications after symptomatic versus antibiotic treatment: follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Ger Med Sci. 2016;14:Doc01. doi: 10.3205/000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 63 kb)

(DOCX 29 kb)