Abstract

The explosion of the coronavirus onto the global stage has posed unprecedented challenges for governance. In the United States, the question of how best to respond to these challenges has fractured along intergovernmental lines. The federal government left most of the decisions to the states, and the states went in very different directions. Some of those decisions naturally flowed from the disease's emerging patterns. But to a surprising degree, there were systematic variations in the governors’ decisions, and these variations were embedded in a subtle but growing pattern of differences among the states in a host of policy areas, ranging from decisions about embracing the Affordable Care Act to improving their infrastructure. These patterns raise fundamental questions about the role of the federal government's leadership in an issue that was truly national in scope, and whether such varied state reactions were in the public interest. The debate reinforces the emerging reality of an increasingly divided states of America.

As the United States tackled the COVID‐19 outbreak, it could have traveled down several different roads. In South Korea, the national government took strong action with aggressive testing. In Germany, Angela Merkel's aggressive embrace of science produced a relatively successful early campaign against the virus (Miller 2020). In the United States, however, President Donald Trump consciously avoided carving out a clear role for the federal government. Instead, as he wrote in a letter to Senator Charles E. Schumer (D‐NY), “the Federal Government is merely a back‐up for state governments.” 1 The federal response was to avoid a national strategy on what was clearly a national problem.

That puts the American response apart from the rest of the world. There was a different response in every state—as well as in the District of Columbia and in territories across the world from Guam to Puerto Rico. In no other country was the level of friction between the national and subnational governments as high as in the United States. Even in the United Kingdom, where an election weeks before the outbreak of the virus led to a wrenching national debate over keeping the country together, national unity was substantially higher. At the core of these differences—and these frictions—is America's system of governance and, especially, its deep‐rooted traditions of federalism. These traditions, in turn, shaped two important patterns. First, the decisions in each state were not just reactions to the virus but were embedded in a far longer and much wider policy stream. Second, these decisions clustered in important ways, with groups of states following different tactics. A careful look at these interrelated forces provides keen insight into the policy streams of American federalism—and to examine American federalism is to provide insight into the differences in the state responses.

The States as Laboratories

There were many arguments for allowing the states to take the lead. To begin with, the virus did not flare up uniformly. It first hit in Washington State, then in California, and then emerged with a horrible vengeance in New York State. For some states, especially in the middle part of the country, the virus came much later. As the disease developed, it often had surprising patterns, hitting both urban areas and rural hot spots, especially around food processing plants. Crafting a single strategy to try to get ahead of these fast‐moving problems proved extraordinarily difficult. Indeed, as is always the case with big issues that require an emergency response, all disasters are local (FEMA 2013).

Then there was the long‐standing argument that the states should lead because they are “laboratories of democracy,” the phrase coined by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. 2 Brandeis enthusiastically argued for experimentation in the states, and David Osborne's (1990) book of the same name reinforced the case. COVID‐19 seemed to be a problem tailor‐made for state‐based laboratories: individual states could experiment; they could assess what produced the best outcomes; successful experiments could be shared with other states; less successful experiments would be discarded; and the federal government could lead the national effort based on evidence about what worked. COVID‐19 was a policy problem of enormous complexity and uncertainty. No one knew quite what it was, how it behaved, or how best to treat it. Why not allow the states that confronted it first try different strategies so that other states, with cases that developed later, could benefit from the successes? Indeed, there is strong evidence that the state‐by‐state decisions to invoke shelter‐in‐place orders significantly reduced the spread of the virus (Courtemanche et al. 2020). But the bigger question remains: Was it advisable for the federal government to rely on the decisions of state and local governments to frame policies to control and mitigate a virus that was truly national in scope? That is a question that framed the initial debates about how best to respond to pandemic, and it will cast a deep shadow over American federalism for a very long time.

Then there is the enduring argument for “sorting out” government's functions. Is COVID‐19 a problem that state officials ought best to manage, since the most important resources in tackling it lie at the state and local levels? In Federalist No. 51, after all, James Madison argued for the virtues of a “compound republic” with “two distinct governments,” federal and state. Martha Derthick embraced that sorting‐out notion and argued for clear lines of responsibility between the federal government and the states (Derthick 2001; see also Anrig 2010; Bednar 2011; Edwards 2009; Hoover Institution Task Force on K–12 2012; Kendall 2004; Nivola 2005; Oates 1972). The debate, of course, was rooted in the remarkably “ambiguous division of authority” at the core of American federalism, as John Donahue (1997, 5) contended. Perhaps in the ambiguity of legal and constitutional there was authority—perhaps even a mandate—for state governments to carve out their own paths.

And that is just what they did, most notably in the early weeks of the crisis, through governors’ decisions about whether—and when—to lock down their economies. Indeed, in the first phase of the outbreak, the lockdown decision was the central public policy action. Because there was no proven treatment for the virus and no vaccine to prevent it, the best way to prevent its spread was to keep people far enough away from each other to reduce its spread. Otherwise, public health officials warned, the disease would overrun communities and overwhelm hospital emergency rooms, intensive care units, and the supply of ventilators. Reducing economic activity and social interaction was, public health officials believed, the only real line of defense.

One of the first lockdown decisions came from National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) president Mark Emmert, who announced on March 11 that the men's and women's basketball tournaments would be played to empty arenas. That decision startled the country, since a March without March Madness crowds seemed unthinkable. But then a few days later, the NCAA canceled the entire tournament, in response to what NCAA vice president Dan Gavitt called a “global health crisis” (Gavitt 2020). Within days, the governors began locking down their states, beginning on March 19 in California and rippling from there across the country. By the end of March, 32 states had issued lockdown orders. Eleven more states followed in the first week of April, but in the end, seven states (Arkansas, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming) decided not to lock down at all (Ballotopedia 2020). The lockdown decision was invariably one of the most difficult decisions most governors had ever had to make. And the decision to lock down before the end of March proved an important measure of the states’ decisions about responding to the outbreak.

What forces shaped these decisions? It is possible to imagine two approaches. One is that the governors’ decisions would be built on evidence from public health experts. The other is that these decisions would, instead, flow from the broader stream of public policy decisions over the years. It is certainly the case that, especially for the handful of states in which the virus proved especially virulent in its opening weeks, public health experts shaped the strategy. But, as we shall see, as the outbreak spread, it was the broader policy stream, not evidence‐based policies, that dominated. The state‐by‐state decisions about locking down the economy by the end of March provides the important touchstone.

The pivotal question was whether the lockdown decisions followed the seriousness of the outbreak. In fact, the 10 states that experienced the highest death rate by mid‐April were, in fact, far more likely to lock down by the end of March. The death rate provided, sadly, the best evidence of the seriousness of the disease, and it was the most uniform national measure, even though reporting problems made even this measure hard to collect. Because the disease can take several weeks to incubate and inflict its most serious damage, this April death rate provides an indicator of the decisions that the governors faced at the end of March. For the rest of the states, however, there was no pattern between the death rate and the lockdown decision. In fact, the states with the lowest death rate were about as likely to lock down early as those with much higher death rates (see table 1). Moreover, by the middle of May, the rate of new deaths was 12 percent higher in the states that did not lock down in March (Fox et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Governors’ Decisions to Lock Down Their States Compared with the Death Rate

| Deaths/100,000 | Locked Down in March |

|---|---|

| Highest 10 | 9 of 10 |

| Next‐highest 10 | 6 of 10 |

| Middle 10 | 6 of 10 |

| Next‐lowest 10 | 7 of 10 |

| Lowest 10 | 5 of 10 |

Source: COVID‐19 Tracking Project, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/coronavirus‐us‐cases‐deaths/?itid=hp_hp‐banner‐low_web‐gfx‐death‐tracker%3Ahomepage%2Fstory‐ans. Data as of April 26, 2020.

The timing of the governors’ decisions, therefore, was not directly connected with the seriousness of problems they faced. What, then, were they connected with? The states were not operating as “laboratories of democracy,” with different states experimenting with different policy decisions depending on the seriousness of the problem they faced. COVID‐19 created a laboratory, but one without experimentation. The states’ decisions flowed instead from a different pattern.

Systematic Variations

Although the early focus of the crisis centered on a handful of states with a big surge in cases, it quickly became clear that the virus was a genuine emergency, a national crisis instead of a regional outbreak. No part of the country, no matter how far removed from the first cases, was immune. Officials in Iowa discovered 16 cases among travelers recently back from a cruise on Egypt's Nile River. The same trip sparked cases in Texas and Maryland (Helderman et al. 2020). COVID‐19 proved an angry aggressor that paid no attention to borders of any kind.

The pattern of state responses, however, followed the broader stream of political and policy choices that were already in place. Table 2 shows that the states that locked down in March voted for President Trump at a much lower rate and tended to have weaker Republican control of their state governments.

Table 2.

Governors’ Decisions to Lock down their States Compared with Partisan Control

| Republicans Control Governorship, Both Houses of State Legislature | Democrats Control Governorship, Both Houses of State Legislature | Split Partisan Control | Nonpartisan (Nebraska) | Trump Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March lockdown | 6 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 45.7 |

| No March lockdown | 14 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 55.3 |

Source: For state partisan control, Nuttycombe (2020).

The lockdown decisions were also consistent with a broad collection of disparate policy decisions over a far longer time. For example, consider the connection between governors’ lockdown decisions and the states’ previous decisions to expand Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed in 2010. Barack Obama came into office committed to providing health care for all Americans, but he faced two inescapable forces: opposition to the federal government providing health care, which meant he needed to focus on creating a program of health insurance, and opposition to the federal government providing health insurance, which meant he needed to craft a strategy that relied heavily on the states. The ACA thus was not so much a program of federal health insurance as a federal program encouraging the states to create their own state‐based health insurance exchanges and to decide whether to expand the Medicaid program to more recipients. As Sommer (2013) pointed out, the program was “a patchwork of related but not identical strategies, solutions, and regulations.” Some states embraced the ACA and used it to expand health care coverage to their citizens. Others strongly pushed back and refused to expand their Medicaid programs under the ACA's provisions.

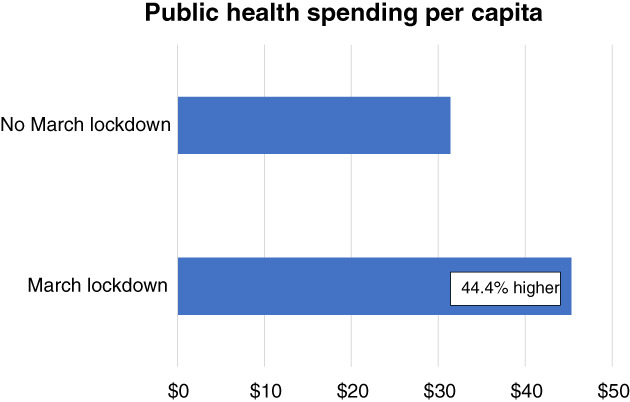

The previous decisions about expanding Medicaid tended to match the governors’ decisions to lock down their states. In the states where governors locked down their economies in March, 87.5 percent had earlier decided to expand Medicaid under the ACA. In the states where the governors did not lock down in March, almost two‐thirds had decided not to expand Medicaid (see table 3). There were also stark differences in the states’ investment in their public health programs. As figure 1 shows, the states that locked down in March also spent significantly more on public health spending—44.4 percent more per capita, in fact.

Table 3.

Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act

| Expansion | No Expansion | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| March lockdown | 28 | 4 | 32 |

| No March lockdown | 7 | 11 | 18 |

Source: Calculated by author.

Figure 1.

Public Health Spending Per Capita

Source: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2020). Data are for 2018.

The differences in public health investments spilled over into a remarkably broad range of other policy outcomes. Consider a wide collection of policy areas: environmental performance, infant mortality, eighth‐grade reading proficiency, poverty rate, the condition of the state's infrastructure (as measured by the percentage of the total bridges that were judged deficient). Table 4 shows a consistent and significant difference in the two groups of states. The states that locked down their economies in March fared better on all of these indicators. Policy outcomes in the states not only vary widely, but the differences among them are growing (Kettl 2020).

Table 4.

Differences between States That Locked Down in March and Those That Did Not

| Environmental Performance (ACE Index) | Infant Mortality Rate (Per 1,000 Live Births) | Eighth‐Grade Reading Proficiency (NAEP Index) | Poverty Rate 2014–16, Average (% of People in Poverty) | Deficient Bridges (% of Total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March lockdown | 15.96 | 5.7 | 33.9 | 12.7 | 7.5% |

| No March lockdown | 7.51 | 6.4 | 31.2 | 13.7 | 8.1% |

| Difference for March lockdown states | 112.4% higher | 11.0% lower | 8.7% higher | 6.8% lower | 6.9% lower |

In the states’ response to the virus, there certainly were partisan differences. The early‐outbreak states—especially Washington, California, and New York—tended to disproportionately lean Democratic, and their Democratic governors tended to among the first and most vocal champions of an aggressive governmental response. The states where the virus hit latest tended to lean Republican. But it is much too simple to argue that the most important strategic decisions were purely the product of partisanship. They are embedded in a much wider, much deeper, and even more important policy stream that has been reshaping American public policy for a far longer time.

The Silent Tsunami

The governors’ decisions about locking down their economies arose out of a silent tsunami. America, of course, is no stranger to disasters, both man‐made and natural. That is why, in fact, Congress created the Department of Homeland Security in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks, and why the states have followed suit. Emergency management experts have long embraced the idea of an “all‐hazards” approach to disasters: create a robust but nimble capacity to respond to disasters, however they emerge, because it is impossible to guess which disaster will occur next and because the response to many disasters builds on a core collection of resources (FEMA 1996; OECD 2018).

The COVID‐19 assault fits within the all‐hazards approach. Indeed, emergency planners had built the capacity for a strong public health response into their response strategy, especially since the September 11 terrorist attacks, and experts had warned about the risks of a global pandemic (Center for Health Security 2019; Nuki 2020). Compared with most of the all‐hazard planning, however, COVID‐19 was a silent tsunami, in several important respects. First, unlike the terrorist attacks or Hurricane Katrina, which followed four years later, the virus was invisible to the public. An invisible microscopic killer, it took a skilled team of artists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to bring it to life with an artistic rendition that quickly became iconic (Kallingal 2020). That stood in dramatic contrast to the terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina, where the scale and importance of the disasters were both clear to all and unmistakable in scope. Second, the root of the problem was unclear, as was what to do about it. Compared with Hurricane Katrina, where the nature of the problem (epic flooding and wind damage) and how to attack it (rescue those the storm had left isolated and devastated), COVID‐19 generated only uncertainty. That carried over, third, to the question of how to create a longer‐term strategy because, the deeper state officials got into the crisis, the more uncertainty they faced about the disease: what it was, how to slow it, how to recover from it, and how to rebuild communities in the long term. Fourth, the scale of the problem was far greater than any previous recent disaster. COVID‐19 hit with a force of 1,000 or more Katrinas, leaving no part of the country unspared. The governors were faced not only with a vast array of problems they could scarcely identify (compare Kettl 2014). They were overwhelmed with what Donald Rumsfeld would have called both “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns” (Graham 2014).

Confronting enormous punctuations to their equilibrium (see Baumgartner and Jones 1993; Baumgartner, Jones, and Mortensen 2014; Jones and Baumgartner 2005), the governors could have used the virus to trigger big changes to their states’ existing policy regimes. Rather, they fell quickly back to the established and accepted patterns of the political culture and policy decisions that had grown up within their states. Indeed, the larger the crisis became, the stronger the incentives were for governors to slide back into the relatively familiar, politically proven policy streams, shaped by the problems, policies, and politics of the past (Kingdon 1984). Even though these past practices risked falling badly out of sync with what an effective response to the disease demanded, it was far less risky to fall onto what the policy streams in each of their states had produced over the years. However, because these policy streams have becoming increasingly divided over the years, with the United States becoming a land of divided states (Kettl 2020), COVID‐19 served only to reinforce the divisions that had already developed in the country. That, in turn, reinforced the growing inequality among the states that had emerged on a wide policy front.

Intergovernmental Friction

The outbreak of COVID‐19 has laid bare a trio of fundamental—and fundamentally important—issues at the core of modern American democracy: the relationship between the federal government and the states, the relationship among the states, and the relationship between the state governments and their localities. In the 1960s, there was a budding consensus that the federal government should take a strong steering role, shaping national policy through a robust system of grants that state and local governments were bound to find irresistible. In part, that was because the federal government came to channel the nation's ambition in fighting wars against problems ranging from poverty to health care. In part, that was also because of lingering distrust of state and local governments flowing from the days of segregation. There was a strong sense that if the nation was going to make large strides, the federal government would need to strap on the boots and fund the effort.

In the decades that followed, however, there was a growing concern that the federal government had overreached, that state and local governments had powerful administrative machinery of their own, and that for both political and policy reasons it made sense to match national programs to local conditions. Along the way, it became increasingly hard for the federal government to reach consensus on any decision of major import. Congress became, as Mann and Ornstein (2006) put it, a “broken branch,” often struggling to move important pieces of legislation. Any major proposal for domestic initiatives immediately became wrapped up in fierce battles about the size of the government and, in the pre‐COVID‐19 days, the size of the deficit.

That increasingly left domestic policy leadership to the states, and the states’ preeminence in turn produced a widely varying patchwork of state government responses to COVID‐19. The federal government did not speak with a single voice, and the president often downplayed the seriousness of the outbreak. At the end of February, President Trump called the virus the “new hoax” of the Democrats, and he suggested that “the press is in hysteria mode” (Palma 2020). Meanwhile, different messages came from the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the cabinet secretaries overseeing them. Of course, the federal government's power to lock down the states was limited, even with President Trump's decision on March 13 to invoke the Stafford Act, which declared a national emergency. But from the procurement of tests to the distribution of ventilators, the states remained largely on their own and often in competition with each other. Without national coordination of the production, price, and allocation of scarce medical supplies, the states ended up competing with each other, and with the federal government, for ventilators and personal protective equipment. “We are literally bidding up the prices ourselves,” complained Governor Andrew Cuomo (D‐NY), pointing to an increase of ventilator prices from $25,000 to $40,000. The result was what economists would predict: escalating demand, in the absence of much greater supply, produced a rapid increase in the price (Feldman 2020). Within states like Georgia and, especially, Texas, moreover, the frictions between the state and local governments boiled over, with fierce battles over who had the authority to set rules for citizens—and which businesses could open when, and under what circumstances.

Even the basic question of where the problem was most serious and how fast it was spreading was impossible to answer because there was no common language for charting the problem, as what defined the problem depended on tests for the virus and different states had different strategies for testing. Some states reported only tests that produced positive results. Some states included negative tests, while others (including Maryland and Ohio) did not. Some states had a significant lag in reporting test results, and some states were reluctant to report test results at all. Some states reported results different from public and private labs. Virginia at first combined results from antibody and diagnostic tests, an approach that compared apples with oranges, and then changed its reporting metrics as the virus wore on. In some states, officials reported the number of positive results compared with the number of specimens taken, which produced a higher infection rate than reporting on the number of individuals tested, because many individuals often had many tests over the course of their disease. Georgia officials admitted that they had bungled a chart that incorrectly showed a downward trend. “Our mission failed. We apologize,” the governor's spokesperson said (Mariano and Trubey 2020). The architect of Florida's virus dashboard was removed, leading critics to charge that the state government was attempting to censor science (Sassoon 2020). Across the states, the infection rate ranged from 5 to 10 percent of tests conducted, even though it was highly unlikely, of course, that the infection rate was twice in high in some states than others (Schulte 2020).

The intergovernmental confusion meant that it was impossible to get a full and accurate picture of the disease, its spread, and its health implications. In fact, the benchmark data for tracking COVID‐19 increasingly came not from governmental sources but, instead, from private and nonprofit organizations. Johns Hopkins University's Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu) was the touchstone for most analysis and reporting. At the University of Washington, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (http://www.healthdata.org/covid) produced the models estimating the likely spread of the disease, on which many federal and state officials depended. At the University of Texas, data scientists developed a separate model because they were unhappy with methodological changes in some of the other tracking systems (https://covid‐19/tacc.utexas.edu). A collaborative of media organizations created their own COVID Tracking Project (https://covidtracking.com).

Many of the data flowed from health care providers to county health departments, from these county health departments to state health departments, and from there to the CDC. The CDC data, in turn, helped fuel the analytical engines at Johns Hopkins, the University of Washington, and the media conglomerates. But when it became apparent that the illness affected minority populations more than others, only 35 states reported the death rate by race, and just two shared information on testing by race. 3 Other data came from social distancing measures derived from mobile phones (Woody et al. 2020), but relying on those data generated debates about privacy.

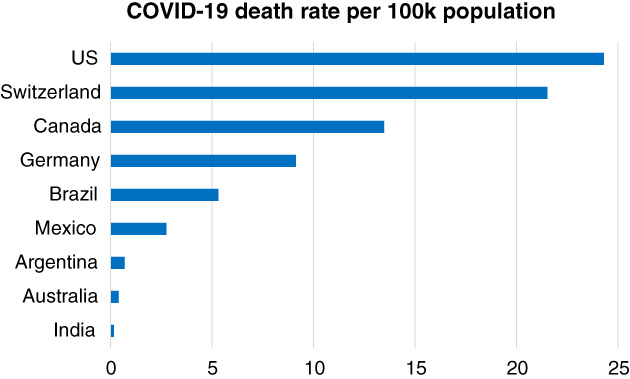

The federal government played a weak steering role for the nation's COVID‐19 response. Indeed, it never framed a truly national strategy to deal with the virus or spoke with a clear national voice on how best to handle it. That left each state to steer its own course, often without a sound base of evidence on which to make decisions. States competed against each other and often moved in very different directions. Other nations, of course, struggled mightily to deal with the large and uncertain course of the disease. But in no other country were the frictions between the national and subnational governments or the variations in strategies among the regions so great. In a mid‐2020 survey, the Edelman Trust Barometer found a larger gap in trust between the national and local governments in the United States than in any other government—four times higher, in fact, than the average of 11 other countries that were surveyed. 4 Moreover, in no other country with a federal system of government was the death rate in the first two months of the pandemic as high as in the United States (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

COVID‐19 Death Rate per 100,000 Population

Source: Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center, “Mortality Analyses,” https//coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Data as of May 10, 2020.

Time will chart the broader implications of the tensions within America's system of government, but the evidence is clear that the intergovernmental frictions—between the federal and the state governments, between the state governments, and between state and local governments—were high and that these frictions had real impact on the health of Americans.

The evidence from the critical initial decisions to lock down the state revealed stark differences among the states. Indeed, the best predictor of the states’ decisions was where the states had already stood in the broad stream of policy decisions and outcomes, ranging from whether to expand Medicaid and how much to invest in public health to their ongoing policies about environmental quality and infrastructure investment. America might be a land where all people are created equal. But with respect to COVID‐19, as in many other policy areas, the risks citizens took and the government they got increasingly depended on where they lived. Indeed, the early evidence from the stark differences between the states was that the effectiveness of the state governments’ responses varied widely, and that Americans in some states were exposed to far greater risks because of the decisions their state governments made.

One of the enduring questions that emerges from the COVID‐19 outbreak is whether governance in the United States failed—or at least did not succeed as Americans needed it to—precisely because it relied so heavily on the states as laboratories, which produced such wide‐ranging experiments. Did some states develop strategies that, given the problems they faced, produce significantly better outcomes? Did frictions in the system—between Washington and some states, between many states, and between some state capitols and their local governments—create much higher risks and cost more lives?

In particular, it will be important to probe the central question of American federalism in the case of COVID: Should the federal government have played a far stronger leadership role? One argument is that a more aggressive federal government could have devised a testing regimen much earlier, ensured that the country geared up its production of testing supplies and personal protective equipment, reduced the competition among the states for supplies, developed a national dashboard for measuring the spread of the virus and the effectiveness of interventions, and directed resources where they were most needed. A counterargument is that a stronger federal role would only have escalated dysfunction, immobilizing the states that developed early and aggressive actions and subjecting the national response to epic problems of coordination. These questions are urgent and require searching, sustained examination, because it is impossible to escape the conclusion that the country's initial response was significantly less successful than in other countries and that its system of federalism lies at the roots. Its clumsy response, in turn, weakened the public's trust and widened political polarization, at precisely the time that citizens and business leaders struggled to determine who to believe as the even tougher decisions about reopening the economy came to center stage. These are issues that cut to the heart of governance in the United States and frame the twenty‐first century's version of the debates that have been at the core of democracy in America since the nation's founding.

The Public Interest on a Wobbly Foundation

The COVID‐19 outbreak was, by any measure, one of the most challenging public policy problems in American history—and indeed one of the most complex that modern governments anywhere have faced. But amid the global challenges, the United States stands apart because of the highly devolved nature of its response. Although COVID‐19 became a clearly national problem, the country did not meet it with a national response. Indeed, the Washington Post’s editorial board argued that creating a robust national testing system was “a uniquely federal responsibility,” a strategy that should have been “a Manhattan Project for the pandemic age.” Instead, President Trump “left the job to governors, and the nation is staggering under the consequences” (Washington Post 2020). For the success that the governors did have, the president took credit. He tweeted, “Remember this, every Governor who has sky high approval on their handling of the Coronavirus, and I am happy for them all, could in no way have gotten those numbers, or had that success, without me and the Federal Governments help. From Ventilators to Testing, we made it happen!” 5

The nation's strategy was built on a wobbly foundation, riven by great tensions of federal versus state power, and then with the states pulling in different directions. The state reactions, in turn, matched the different policy strategies of the states in many other policy areas as well. It is one thing to rely on “laboratories of democracy” to experiment with policy initiatives and determine which ones deserve wider adoption. But it is quite another for the nation's response to a truly national problem to vary so greatly. The American response to COVID‐19 underlines a growing truth about American public policy: The United States is a country with states moving in different directions, and these different directions have grave consequences for the well‐being of Americans. The nation faced fundamental choices at the start of the pandemic: first, whether the federal government would lead on issues that were truly national in scope, but instead it pushed responsibility to the states; and then whether the states would seize the punctuation of the equilibrium to create a new governance regime, but instead they slid back into long‐established and increasingly disparate patterns. At the core, this is the price of American federalism. The virus frames the question of whether that price is simply too high to pay when faced with the biggest policy challenges of the twenty‐first century.

Is this price the inevitable result of James Madison's strategy in 1787 to balance federal and state power, to nudge the Constitution toward ratification? The long history of American democracy is, in fact, one in which the original compromise has fed division as well as experimentation in the laboratories of democracy. But during the COVID‐19 pandemic, that grand compromise exacted a big price, with a federal government unwilling to act to frame a genuine national policy, with states going down different roads, and where the entire creaky system was too slow to act on a problem that paid no attention to state boundaries and that moved faster than government's ability to keep up. Alexander Hamilton framed an alternative vision, of a robust federal government powerful enough to push forward national policies to attack national problems. That, indeed, was the approach advanced with great success in the first weeks by Germany's Angela Merkel, who took on her own state governments (Kupferschmidt and Vogel 2020). Even in Germany, tensions between the central government and the states began rising, although the national government was not shy about forcefully crafting a robust national policy, calling out the states for reopening too quickly and for protecting the strong results that the country won in the important early weeks of the very long campaign against the virus.

The insidious complexity of the virus quickly demonstrated that the first decisions made by government officials were only the initial salvos in a far longer war that was to test the systems of government around the world. But it is impossible to escape the conclusion that the United States faced the virus with a system of governance that was not up to the job, in part because the initial outcomes were less positive than in other federal systems and in part because the treatment of citizens varied so greatly across the country. And the widely—sometimes wildly—varying responses of its governance meant that citizens suffered more than they needed to—and that they suffered more in some places than others.

Decisions about COVID‐19 followed the broader strategies already in place: for the federal government to pass the buck to the states, and for the states to go their own ways, often in different directions. The result was a system of states divided, with deep and enduring implications for Americans and the pursuit of “equal protection of the laws,” as the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution so elegantly puts it.

Biography

Donald F. Kettl is Sid Richardson Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of, among other works, The Divided States of America: Why Federalism Doesn't Work (Princeton University Press, 2020) and The Politics of the Administrative Process, 8th ed. (Sage, 2020).

Email: kettl@austin.utexas.edu

Notes

Letter to Senator Charles E. Schumer, April 2, 2020, https://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000171‐3f7b‐d6b1‐a3f1‐fffb5e270000&nname=playbook&nid=0000014f‐1646‐d88f‐a1cf‐5f46b7bd0000&nrid=00000159‐176e‐db99‐ab5d‐bffe84ac0002&nlid=630318 (accessed May 29, 2020).

New State Ice Co. v. Lieberman, 285 U.S. 262 (1932).

Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center, “State COVID‐19 data by Race,” https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/racial-data-transparency (accessed May 29, 2020).

Edelman Trust Barometer 2020, https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2020‐05/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Spring%20Update.pdf (accessed May 29, 2020).

Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), “Remember this, every Governor who has sky high approval on their handling of the Coronavirus, and I am happy for them all, could in no way have gotten those numbers, or had that success, without me and the Federal Governments help. From Ventilators to Testing, we made it happen!,” Twitter, May 12, 2020, 7:56 a.m., https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1260177007490600960.

References

- American Road Transportation Builders Association . 2020. ARTBA 2020 Bridge Report. https://artbabridgereport.org/reports/ARTBA%202020%20Bridge%20Report%20‐%20State%20Ranking.pdf [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Anrig, Greg . 2010. Federalism and Its Discontents, Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, no. 15. https://democracyjournal.org/magazine/15/federalism‐and‐its‐discontents/ [accessed May 29, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Ballotopedia . 2020. State Government Responses to the Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Pandemic, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/State_government_responses_to_the_coronavirus_(COVID‐19)_pandemic,_2020 [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Baumgartner, Frank R. , and Jones Bryan D.. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, Frank R. , Jones Bryan D., and Mortensen Peter B.. 2014. Punctuated‐Equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking. In Theories of the Policy Process, 3rd ed., edited by Sabatier Paul and Christopher M.. Weible, 155–187. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bednar, Jenna . 2011. The Political Science of Federalism. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 7: 269–88. 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102510-105522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health Security . 2019. Event 201. https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/event201/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Courtemanche, Charles , Garuccio Joseph, Le Anh, Pinkston Joshua, and Yelowitz Aaron. 2020. Strong Social Distancing Measures in the United States Reduced the COVID‐19 Growth Rate. Health Affairs. Published online May 14. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derthick, Martha . 2001. Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, John D. 1997. Disunited States: What's at Stake as Washington Fades and the States Take the Lead. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Chris . 2009. Fiscal Federalism. In Cato Handbook for Policymakers, 7th ed., 63–71. Washington, DC: Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato‐handbook‐policymakers/2009/9/hb111‐5.pdf [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Feldman, Amy . 2020. States Bidding against Each Other Pushing Up Prices of Ventilators Needed to Fight Coronavirus, NY Governor Cuomo Says. Forbes, March 28. https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyfeldman/2020/03/28/states‐bidding‐against‐each‐other‐pushing‐up‐prices‐of‐ventilators‐needed‐to‐fight‐coronavirus‐ny‐governor‐cuomo‐says/#1dd9926f293e [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Fox, Joe , Mayes Brittany Renee, Schaul Kevin, and Shapiro Leslie. 2020. 78,890 People Have Died from Coronavirus in the U.S. Washington Post, May 10. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/coronavirus‐us‐cases‐deaths/?itid=hp_hp‐banner‐low_web‐gfx‐death‐tracker%3Ahomepage%2Fstory‐ans [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Frost, Riordan , and Fiorino Daniel. 2018. The State Air, Climate, and Energy (ACE) Index. Email communication with the author, March 13.

- Gavitt, Dan . 2020. NCAA SVP Dan Gavitt: No DI Men's and Women's Basketball Brackets Will Be Released This Year. NCAA, March 15. https://www.ncaa.com/live‐updates/basketball‐men/d1/ncaa‐cancels‐mens‐and‐womens‐basketball‐championships‐due [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Graham, David A . 2014. Rumsfeld's Knowns and Unknowns: The Intellectual History of a Quip. The Atlantic, March 27. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/03/rumsfelds‐knowns‐and‐unknowns‐the‐intellectual‐history‐of‐a‐quip/359719/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Helderman, Rosalind S ., Hannah Sampson, Dalton Bennett, and Andrew Ba Tran. 2020. The Pandemic at Sea. Washington Post, April 25. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/politics/cruise‐ships‐coronavirus/?itid=hp_hp‐top‐table‐high_cruisefallout‐1020am%3Ahomepage%2Fstory‐ans [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Hoover Institution Task Force on K–12 Education . 2012. Choice and Federalism: Defining the Federal Role in Education. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/choice‐and‐federalism.pdf [accessed May 29, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Bryan D. , and Baumgartner Frank R.. 2005. The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kallingal, Mallika . 2020. Meet the Illustrators Who Gave the Coronavirus Its Face. CNN, April 18. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/17/us/coronavirus‐cdc‐design‐trnd/index.html [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Kendall, Douglas T. , ed. 2004. Redefining Federalism: Listening to the States in Shaping “Our Federalism”. Washington, DC: Environmental Law Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kettl, Donald F. 2014. System under Stress: Homeland Security and American Politics, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kettl, Donald F. 2020. The Divided States of America: Why Federalism Doesn't Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, John W. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt, Kal , and Vogel Gretchen. 2020. Reopening Puts Germany's Much‐Praised Coronavirus Response at Risk. Science, April 27. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/reopening‐puts‐germany‐s‐much‐praised‐coronavirus‐response‐risk [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Mann, Thomas E. , and Ornstein Norman J.. 2006. The Broken Branch: How Congress Is Failing America and How to Get It Back on Track. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano, Willoughby , and Trubey J. Scott. 2020. “It's Just Cuckoo”: State's Latest Data Mishap Causes Critics to Cry Foul. Atlanta Journal‐Constitution, May 13. https://www.ajc.com/news/state‐regional‐govt‐politics/just‐cuckoo‐state‐latest‐data‐mishap‐causes‐critics‐cry‐foul/182PpUvUX9XEF8vO11NVGO/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Miller, Saskia . 2020. The Secret to Germany's COVID‐19 Success: Angela Merkel Is a Scientist. The Atlantic, April 20. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/04/angela‐merkel‐germany‐coronavirus‐pandemic/610225/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Nation's Report Card . 2020. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NEAP) Results. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/profiles/stateprofile?chort=2&sub=RED&sj=AL&sfj=NP&st=MN&year=2019R3 [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Nivola, Pietro . 2005. Why Federalism Matters. Policy Brief Series, Brookings Institution, October 1. https://www.brookings.edu/research/why‐federalism‐matters/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Nuki, Paul . 2020. Exercise Cygnus Uncovered: The Pandemic Warnings Buried by the Government. The Telegraph, March 28. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/03/28/exercise‐cygnus‐uncovered‐pandemic‐warnings‐buried‐government/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Nuttycombe, Chaz . 2020. The State of the States: The Legislatures. University of Virginia Center for Politics, May 7. http://centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/articles/the‐state‐of‐the‐states‐the‐legislatures/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Oates, Wallace E. 1972. Fiscal Federalism. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, David . 1990. Laboratories of Democracy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, Bethania . 2020. Did President Trump Refer to the Coronavirus as a “Hoax”? Snopes, March 2. https://www.snopes.com/fact‐check/trump‐coronavirus‐rally‐remark/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation . 2020. Per Person State Public Health Funding. http://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/rank/117/per‐person‐state‐public‐health‐funding#2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52/a/25/154/false/location [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Sassoon, Alessandro Marazzi . 2020. Florida COVID‐19 Response Loses Data Chief and Transparency. Governing, May 19. https://www.governing.com/next/Florida‐COVID‐19‐Response‐Loses‐Data‐Chief‐and‐Transparency.html?utm_term=Florida%20COVID‐19%20Response%20Loses%20Data%20Chief%20and%20Transparency&utm_campaign=Drawing%20Lessons%20from%20a%20Government%20Protest%20in%20North%20Dakota&utm_content=email&utm_source=Act‐On+Software&utm_medium=email [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Schulte, Fred . 2020. Some States Are Reporting Incomplete COVID‐19 Results, Blurring the Full Picture. Kaiser Health News, March 25. https://khn.org/news/some‐states‐are‐reporting‐incomplete‐covid‐19‐results‐blurring‐the‐full‐picture/ [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Sommer, Alexander H . 2013. State Implementation of the Affordable Care Act. AMA Journal of Ethics, July. https://journalofethics.ama‐assn.org/article/state‐implementation‐affordable‐care‐act/2013‐07 [accessed May 29, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . 2017. Percentage of People in Poverty by State. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/income‐poverty/p60‐259.html [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Washington Post . 2020. This Is Trump's Greatest Failure of the Pandemic. May 11. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/this‐is‐trumps‐greatest‐failure‐of‐the‐pandemic/2020/05/11/29f22f7c‐93ae‐11ea‐82b4‐c8db161ff6e5_story.html [accessed May 29, 2020].

- Woody, Spencer , Tec Mauricio, Dahan Maytal, Gaither Kelly, Lachmann Michael, Fox Spencer J., Meyers Lauren Ancel, and Scott James. 2020. Projections for First‐Wave COVID‐19 Deaths across the US Using Social‐Distancing Measures Derived from Mobile Phones. https://covid‐19.tacc.utexas.edu/media/filer_public/87/63/87635a46‐b060‐4b5b‐a3a5‐1b31ab8e0bc6/ut_covid‐19_mortality_forecasting_model_latest.pdf [accessed May 29, 2020].