Watch the interview with the author

Abbreviations

- COVID‐2019

coronavirus disease 2019

- CSPH

clinically significant portal hypertension

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- EV

esophageal varix

- EVH

esophageal variceal hemorrhage

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- LS

liver stiffness

- LT

liver transplant

- NSBB

nonselective beta blocker

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- Y90

yttrium 90 radioembolization

Management of Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) pandemic has resulted in more than 60,000 deaths in the United States as of April 30, 2020. 1 Although patients with liver disease have been deemed at increased risk for serious illness by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 little is known about the natural history of SARS‐CoV‐2 in liver disease. Patients with advanced liver disease may be at increased risk because of immune dysfunction, frequent hospitalization, high rates of comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, obesity), and decreased access to antiviral therapies that are potentially hepatotoxic (e.g., remdesivir, interleukin‐6 pathway antagonists). In the United States, the prevalence rate of liver disease is 2.3% in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2, 3 and international registries and population‐based data suggest a high mortality in cirrhosis. 4 , 5 However, the true prevalence and impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 on patients with liver disease remains unknown.

Regardless of this prevalence, the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic has caused seismic shifts in the management of patients with advanced liver disease. Lack of access to routine care and decreased yet variable liver transplant (LT) volumes 6 , 7 , 8 have caused significant changes in the management of these patients, the impact of which will be significant.

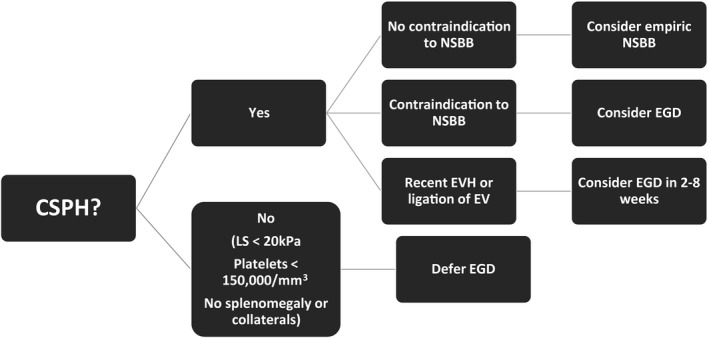

For example, optimal care for patients with cirrhosis includes screening for esophageal varices (EVs) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Several societies have recommended alterations in current practices based on risk assessment for individual patients. 9 , 10 , 11 Although screening for varices with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) among patients with evidence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) is recommended, 12 liver stiffness <20 to 25 kPa alone or combined with platelets >150,000/mm3 can rule out CSPH with high specificity, reducing the urgency for EGD (Fig. 1). In addition, some have also advocated more liberal use of nonselective beta blockers (NSBBs) in those patients without contraindications who cannot undergo EGD. 9 However, some patients cannot safely delay EGD, including those with acute bleeding or those undergoing serial banding until eradication. 12 The timing and availability of EGD thus depends on several factors, including local SARS‐CoV‐2 prevalence, patient risk, physician comfort, and the treatment center’s resources.

Fig 1.

Proposed algorithm for screening and treatment of EVs.

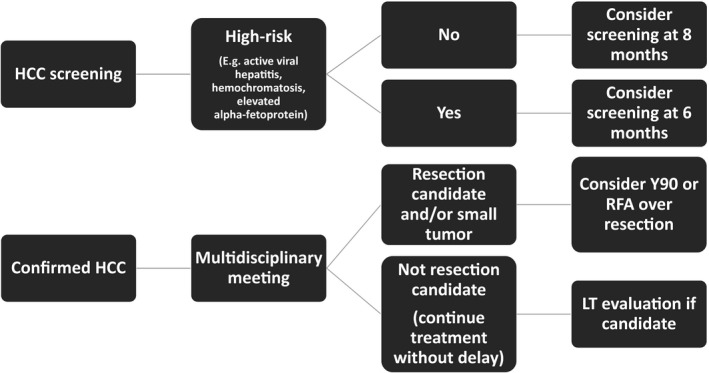

HCC screening practices have also been significantly impacted. Although screening every 6 months is recommended, 13 the optimal interval based on tumor doubling time is 4 to 8 months. 14 Thus, it is reasonable to marginally prolong HCC screening up to 8 months in selected patients, while being mindful of those with multiple HCC risk factors (Fig. 2). Conversely, in patients with established or indeterminate HCC who require short‐term follow‐up or staging, a multidisciplinary discussion is crucial to select individualized treatments and intervals. 9 , 10

Fig 2.

Proposed algorithm for screening and treatment of HCC.

LT Evaluation and Management of Transplant Candidates

The LT evaluation process requires extensive noninvasive and invasive testing, 15 , 16 and given the appropriate discouragement of in‐person visits, telemedicine should be used to expedite LT evaluation. 9 Data from the Veterans Administration show that telemedicine should be embraced; two recent studies noted that it was associated with a shorter time to transplant listing and ruled out 60% of futile evaluations. 17 , 18

For patients on the transplant wait list, telehealth visits have become increasingly common, and because of difficulties obtaining laboratory testing regularly, the United Network for Organ Sharing has relaxed its requirement on the frequent updating of Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease scores. 19 For patients with HCC, maintaining treatment of active cancer is crucial. Prioritization of locoregional therapies, such as yttrium 90 radioembolization (Y90), 20 that reduce time to tumor progression are essential and may be preferable to surgical resection to reduce hospitalization and recovery times.

Finally, whether to proceed with LT for a listed patient must be individualized and based on the patient’s anticipated wait‐list survival, local SARS‐CoV‐2 prevalence, local availability of resources and staff, and ability to test the donor and recipient. Most organ procurement organizations are testing donors, excluding those who test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 and, in some cases, even those who are deemed high‐risk despite testing negative. 9 , 21 , 22

Management of LT Recipients

There is great concern that transplant recipients with chronic immunosuppression could be at high risk for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and a severe disease course. Because only a limited number of LT recipients with SARS‐CoV‐2 have been reported in the literature, 23 , 24 the risk for infection and severe outcomes remain unknown. In the largest series of transplant recipients to date, of 13 liver recipients, 31% had severe disease. 24 Among the 90 solid organ transplant recipients in this series, 16 (18%) died, including 24% of hospitalized patients and 52% of those who required intensive care. Although time from LT did not significantly predict coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) severity, data from Italy suggest that patients with remote LT on minimal immunosuppression may be paradoxically at high risk for severe disease, 23 highlighting the important role of the immune response in the severe manifestations of the virus and how little is known about the impact of the amount and type of immunosuppression. Expert panels currently disagree about whether decreased immunosuppression is routinely recommended, 9 , 11 , 22 and there is currently no evidence on which to base recommendations. In addition, the safety and efficacy of antiviral and immunomodulatory strategies in transplant recipients are not established. Thus, treatment in this setting must be individualized according to the patient’s severity of disease, comorbidities, and risk for rejection, all of which may evolve over time.

Unanswered Questions

There are many essential unanswered questions regarding the impact of COVID‐19 on transplant candidates and recipients. These include basic incidence and prevalence data, which will help guide testing and management of the transplant wait list. This will require accurate and widely available testing for both active SARS‐CoV‐2 and antibodies indicating prior infection. This must be done quickly to understand whether transplant candidates and recipients are less likely to form antibodies and whether these antibodies confer protection from reinfection. Rapid and accurate testing for the donor and recipient at the time of an offer will be critical to resumption of transplant activities moving forward. We must better understand which aspects of the immune response are helpful or detrimental to tailor immunosuppression management. The risk for SARS‐COV‐2–related hepatic decompensation or graft rejection is unknown. Finally, to the extent that safety can be maintained, we must advocate that transplant candidates and recipients are studied in clinical trials of investigational and novel antiviral therapeutic strategies to ensure that they are not disadvantaged in this therapeutic arena.

Potential conflict of interest: R.R. owns stock in Gilead. E.C.V advises Gilead and has received a grant from Salix.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): cases in the U.S. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): groups at higher risk for severe illness. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html. Accessed April 30, 2020. [PubMed]

- 3. Gold J, Wong K, Szablewski C, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID‐19—Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69;545‐550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. SECURE Cirrhosis Registry . Updates and data. Available at: https://covidcirrhosis.web.unc.edu/updates-and-data/. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 5. Singh S, Khan A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID‐19 among patients with preexisting liver disease in United States: a multi‐center research network study. Gastroenterology. Available at: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyarsky BJ, Chiang TPY, Werbel WA, et al. Early impact of COVID‐19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Am J Transplant. Available at: 10.1111/ajt.15915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. United Network for Organ Sharing . COVID‐19 and solid organ transplant. Available at: https://unos.org/covid/. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 8. Agopian VG, Verna EC, Goldberg D. Changes in liver transplant center practice in response to COVID‐19: unmasking dramatic center‐level variability. Liver Transpl. Available at: 10.1002/lt.25789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fix OK, Hameed B, Fontana RJ, et al. Clinical Best Practice Advice for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: AASLD Expert Panel Consensus Statement. Hepatology. Available at: 10.1002/hep.31281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meyer T, Chan S, Park J.Management of HCC during COVID‐19: ILCA guidance. 2020. Available at: https://ilca-online.org/management-of-hcc-during-covid-19-ilca-guidance/. Published April 8, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 11. Boettler T, Newsome PN, Mondelli MU, et al. Care of patients with liver disease during the COVID‐19 pandemic: EASL‐ESCMID position paper. JHEP Rep 2020;2:100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garcia‐Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, et al. AASLD practice guidelines: portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management. Hepatology 2017;65:310‐335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68:723‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rich NE, John BV, Parikh ND, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrates heterogeneous growth patterns in a multi‐center cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. Available at: 10.1002/hep.31159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Leary JG, Lepe R, Davis GL. Indications for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1764‐1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the AASLD and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology 2014;59:1144‐1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. John BV, Love E, Dahman B, et al. Use of telehealth expedites evaluation and listing of patients referred for liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Available at: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Konjeti VR, Heuman D, Bajaj JS, et al. Telehealth‐based evaluation identifies patients who are not candidates for liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:207‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. United Network for Organ Sharing . Actions address transplant candidate data reporting, candidate inactivation related to COVID‐19. Available at: https://unos.org/news/transplant-candidate-data-reporting-candidate-inactivation-related-to-covid-19/. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 20. Salem R, Gordon AC, Mouli S, et al. Y90 radioembolization significantly prolongs time to progression compared with chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1155‐1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Association of Organ Procurement Organizations . COVID‐19 (coronavirus) Bulletin. Available at: https://www.aopo.org/information-about-covid-19-coronavirus-is-being-released-rapidly-we-will-post-updates-as-we-receive-them. Updated April 20, 2020. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 22. American Society of Transplantation . 2019‐nCoV (coronavirus): FAQs for organ donation and transplantation. Available at: https://www.myast.org/sites/default/files/COVID19%20FAQ%20Tx%20Centers%2003.20.2020-FINAL.pdf. Updated March 20, 2020. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 23. Bhoori S, Rossi R, Citterio D, et al. COVID‐19 in long‐term liver transplant patients: preliminary experience from an Italian transplant centre in Lombardy. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. Available at: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30116-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pereira MR, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, et al. COVID‐19 in solid organ transplant recipients: initial report from the US epicenter. Am J Transplant. Available at: 10.1111/ajt.15941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]