Abstract

Objective

To determine the consistency between CT findings and real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and to investigate the relationship between CT features and clinical prognosis in COVID-19.

Methods

The clinical manifestations, laboratory parameters, and CT imaging findings were analyzed in 34 COVID-19 patients, confirmed by RT-PCR from January 20 to February 4 in Hainan Province. CT scores were compared between the discharged patients and the ICU patients.

Results

Fever (85%) and cough (79%) were most commonly seen. Ten (29%) patients demonstrated negative results on their first RT-PCR. Of the 34 (65%) patients, 22 showed pure ground-glass opacity. Of the 34 (50%) patients, 17 had five lobes of lung involvement, while the 23 (68%) patients had lower lobe involvement. The lesions of 24 (71%) patients were distributed mainly in the subpleural area. The initial CT lesions of ICU patients were distributed in both the subpleural area and centro-parenchyma (80%), and the lesions were scattered. Sixty percent of ICU patients had five lobes involved, while this was seen in only 25% of the discharged patients. The lesions of discharged patients were mainly in the subpleural area (75%). Of the discharged patients, 62.5% showed pure ground-glass opacities; 80% of the ICU patients were in the progressive stage, and 75% of the discharged patients were at an early stage. CT scores of the ICU patients were significantly higher than those of the discharged patients.

Conclusion

Chest CT plays a crucial role in the early diagnosis of COVID-19, particularly for those patients with a negative RT-PCR. The initial features in CT may be associated with prognosis.

Key Points

• Chest CT is valuable for the early diagnosis of COVID-19, particularly for those patients with a negative RT-PCR.

• The early CT findings of COVID-19 in ICU patients differed from those of discharged patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, Tomography, Pneumonia, Thorax

Introduction

A real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test is the gold standard for COVID-19 infection diagnosis. However, sample quality may limit its accuracy. In addition, the RT-PCR test requires a relatively long time. Several studies have compared the consistency between RT-PCR and CT findings [1–5]. In the present study, we aimed to systematically analyze RT-PCR, CT, and the clinical outcome of COVID-19 infection from January 26 to February 4, 2020, to determine whether chest CT was a discriminant for the clinical outcome.

Material and methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hainan General Hospital and written informed consent was gained from each patient.

From January 21, 2020, until February 4, 2020, 36 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection were admitted to our hospitals. Among them, two patients were excluded because chest CT was missing due to the very severe condition of the patient. Thus, 34 patients with chest CT performed in our hospital (NeuViz 128 CT, Neusoft) were included in this study. Chest CT settings were as follows: 120 kV; automatic tube current, 300–496 mA; iterative reconstruction slice thickness, 5 mm.

Four patients did not have a second CT scan. In the other 30 patients, a total of 112 chest CT scans were performed and each patient underwent an average of 4 ± 1 CT scans at a mean interval of 3 ± 1 days. The mean interval between the first and second CT scans was 3 ± 2 days.

CT review

CT images were analyzed by two trained radiologists with 14 years and 8 years of experience (F.C. and H.J.C., respectively). They reviewed the images independently. If there was a disagreement, a third trained radiologist (Y.C.) adjudicated the final decision.

CT scans were evaluated for the following features: (1) lesion number; (2) lesion distribution; (3) initial location of the lesions; (4) lobe involvement; (5) presence; and (6) lesion patterns, including pure ground-glass opacity (GGO) [6], GGO with interlobular septal thickening or reticulation, or intralobular networks in GGO, and GGO with consolidation or cavitation; and (7) other abnormalities including pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy (defined as a lymph node > 1 cm in short-axis diameter), pleural thickening, and pericardial effusion.

A follow-up study was performed in these patients. During follow-up, a semi-quantitative scoring standard was used to quantitatively assess the pulmonary involvement of all lesions according to the area involved [7]. Five lobes of the lung were assessed based on these criteria: 0, no involvement; 1, < 5% involvement; 2, 5–25% involvement; 3, 26–49% involvement; 4, 50–75% involvement; 5, > 75% involvement. The total CT score consisted of the sum of all five lobe scores and ranged from 0 (no involvement) to 25 (maximum involvement). The lesion number, lesion location, initial location of lesions, number of lobes involved, lesion patterns, and scores were compared between discharged patients and ICU patients.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables are demonstrated as a percentage (%). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 21 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

Clinical manifestations

The final cohort consisted of 34 patients. The average time interval between the onset of symptoms and admission was 6.3 ± 5.6 days. The average age was 54.5 years (Table 1). There were 23 (62%) men. All patients had an exposure history. The most common symptoms at the onset of illness were fever (29 [85%] of 34 patients) and cough (27 [79%]) (Table 1). On admission, most patients had a normal (24 [71%] patients) or decreased (9 [26%] patients) white blood cell count. Twenty-three [68%] patients showed lymphopenia (lymphocyte count < 1.0 × 109/L; Table 1), and 27 (79%) patients presented with decreased eosinophil count. Most (25/33 available data [76%]) patients had increased C-reactive protein levels on admission (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients infected with COVID-19

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (38%) |

| Male | 21 (62%) |

| Age (years) (28–73) | 54.5 ± 11.8 |

| Exposure history | 100% |

| Clinical symptoms | |

| Fever | 29 (85%) |

| Cough | 27 (79%) |

| Fatigue | 17 (50%) |

| Nasal congestion | 2 (6%) |

| Rhinorrhea | 1 (3%) |

| Sneezing | 0 (0%) |

| Sputum production | 10 (29%) |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (3%) |

| Sore throat | 7 (19%) |

| Pleura pain | 0 (0%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (3%) |

| Chest tightness | 8 (24%) |

| Biochemical results | |

| White blood cell count (normal range, 3.5–9.5 × 109/L) | 24 normal (71%), 9 (26%) decreased, 1 (3%) increased |

| Lymphocyte percentage (normal range, 20–50%) | 23 normal (68%), 11 (32%) decreased, 0 increased |

| Neutrophil count (normal range, 1.8–6.3 × 109/L) | 27 (79%) normal, 5 (15%) decreased, 2 (6%) increased |

| Lymphocyte count (normal range, 1.1–3.2 × 109/L) | 10 (29%) normal, 23 (68%) decreased, 1 (3%) increased |

| Monocyte count (normal range, 0.1–0.6 × 109/L) | 30 (88%) normal, 0 decreased, 4 (12%) increased |

| Eosinophil count (normal range, 0.02–0.52 × 109/L) | 7 (21%) normal, 27 (79%) decreased, 0 increased |

| Basophil count (normal range, 0–0.06 × 109/L) | 33 (97%) normal, 0 decreased, 1 (3%) increased |

| Red blood cell count; male (normal range, 4.3–5.8 × 1012/L); female (normal range, 3.8–5.1 × 1012/L) | 28 (82%) normal, 4 (12%) decreased, 2 (6%) increased |

| Hemoglobin; male (normal range, 130–175 g/L); female (normal range, 115–150 g/L) | 29 (85%) normal, 5 (15%) decreased, 0 increased |

| Hematocrit; male (normal range, 0.4–0.5); female (normal range, 0.35–0.45) | 27 (79%) normal, 6 (18%) decreased, 1 (3%) increased |

| Mean corpuscular volume (normal range, 82–100 fL) | 32 (94%) normal, 2 (6%) decreased, 0 increased |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (normal range, 27–34 pg) | 32 (94%) normal, 2 (6%) decreased, 0 increased |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (normal range, 316–354 g/L) | 32 (94%) normal, 2 (6%) decreased, 0 increased |

| Red blood cell volume distribution width RDW-CV (normal range, ≤ 15%) | 33 (97%) normal, no decreased, 1 (3%) increased |

| Serum retinol-binding (normal range, 25–70 mg/L) | 12 (43%) normal, 16 (57%) decreased, 0 increased |

| C-reactive protein (normal range, 0.068–8.2 mg/L) | 8 (24%) normal, 0 decreased, 25 (76%) increased |

Chest CT scan revealed the typical abnormalities of COVID-19 pneumonia in 32/34 cases, on admission. The average delay from first symptom onset to CT was 6.4 ± 6.5 days. Among them, 10 (29%) had negative results at the initial RT-PCR. These ten patients all presented with typical positive findings on CT (Fig. 1).

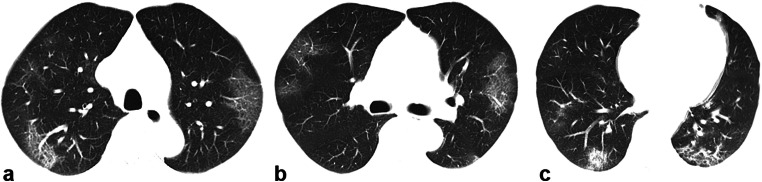

Fig. 1.

A 62-year-old man with a history of exposure, presenting with fever, cough, expectorating white phlegm, nausea, and vomiting. a–c Axial unenhanced chest CT revealed multiple confluent and patchy ground-glass and consolidative pulmonary opacities in the subpleural area bilaterally upon hospital admission on January 29, 2020. The patient underwent a swab test, which was negative for COVID-19 according to a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay on January 30, 2020. The patient underwent a second swab RT-PCR test on January 31, 2020, and the COVID-19 infection was finally confirmed

Six (18%) patients had a single lesion on the first CT scan, two (6%) had double lesions, and most (26, 76%) patients had multiple lesions. The patients with lesions showed a mainly subpleural area (N = 24) distribution or a distribution of both subpleural and centro-parenchymal lesions (N = 10). Among the 26 patients with multiple lesions, 4 (12%) had two lobes involved, 1 (2%) had three lobes involved, 6 (18%) had four lobes affected, and 17 had five lobes affected (50%).

The lower lobes were mostly involved (23, 68%, Table 2), 5 (15%) patients having the upper lobe as the primary lesion location, while 6 (18%) patients with lesions scattered. No one showed lung cavitation or lymphadenopathy. One (3%) patient had small amounts of pleural effusion. Fourteen (41%) patients showed pleural thickening. Three (9%) patients showed mild pericardial effusion.

Table 2.

Manifestations of first CT in 34 patients

| Details of imaging examination | |

| Days from first symptom onset to first CT scan | 6.4 ± 6.5 days |

| Nucleic acid test | |

| Negative in the first RT-PCR | 10 (31%) |

| Positive in the first RT-PCR | 24 (69%) |

| CT imaging stages on admission | |

| Early stage | 15 (44%) |

| Progressive stage | 19 (56%) |

| Absorption period | 0 |

| Lesion number | |

| Single | 6 (18%) |

| Double | 2 (6%) |

| Multiple | 26 (76%) |

| Lesion distribution | |

| Subpleural | 24 (71%) |

| Centro-parenchymal | 0 |

| Both subpleural and centro-parenchymal | 10 (29%) |

| Primary location of lesions | |

| Upper lobe | 5 (15%) |

| Middle lobe | 0 (0%) |

| Lower lobe | 23 (68%) |

| Scattered distribution | 6 (17%) (ICU, 3; no ICU, 3) |

| Number of lobes involved | |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 6 (18%) |

| 2 | 4 (12%) |

| 3 | 1 (3%) |

| 4 | 6 (18%) |

| 5 | 17 (50%) |

| Lesion patterns | |

| Pure ground-glass opacity | 22 (65%) |

| GGO with reticular and/or interlobular septal thickening | 9 (27%) |

| GGO with consolidation | 3 (8%) |

| Cavitation | 0 |

| Other findings | |

| Pleural effusion | 1 (3%) |

| Lymphadenectasis | 0 |

| Pleural thickening | 14 (4%) |

| Pericardial effusion | 3 (9%) |

At early stage (0–4 days after first symptom onset), subpleural GGO was the main feature (Figs. 2a and 3a). Later (5–13 days after first symptom onset), various imaging features including diffuse GGO and consolidation coexisted (Fig. 2b–d), with lesion spread to multiple lobes. At the absorption stage (≥ 14 days after first symptom onset), lesions gradually absorbed.

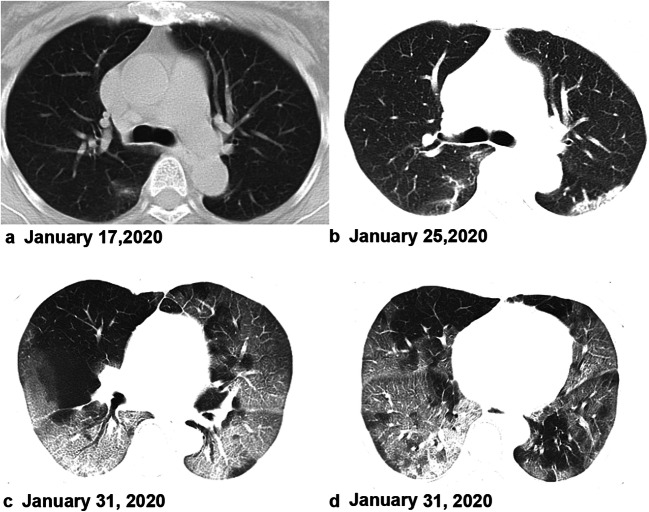

Fig. 2.

A 64-year-old woman, who was a local resident of Wuhan, presented with fever on January 16. Axial unenhanced chest CT revealed patchy ground-glass opacity in the lower lobe of the right lung on January 17 (a). Follow-up CT revealed the infection had progressed and the lesions had extended to a bilateral multilobe distribution with consolidation (b). c, d A 73-year-old man presented with cough 8 days before presentation at the hospital. The CT images on admission showed bilateral, multiple lobular and subsegmental areas of GGO with subsegmental areas of consolidation, indicating the disease was severe

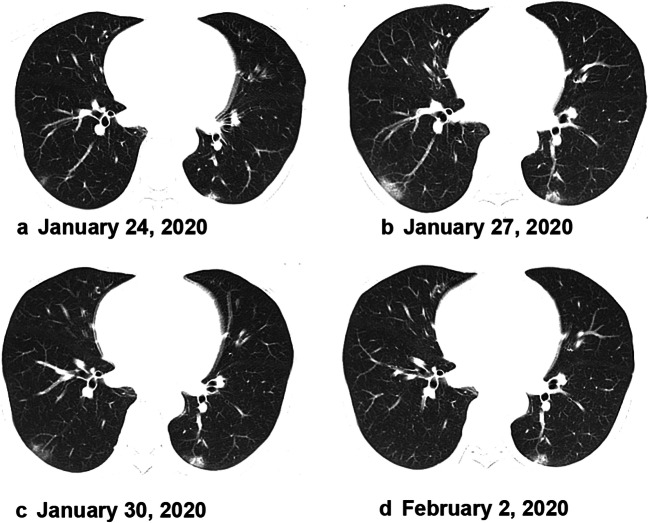

Fig. 3.

A 50-year-old woman with a history of exposure presented with cough and white phlegm for 4 days, accompanied by headache, muscle aches, and no fever. Axial unenhanced CT scan showed small patchy ground-glass lesions in the left lung and the inferior lobe of the right lung upon hospital admission on January 24, 2020 (a). The patient was confirmed with COVID-19 infection on January 26, 2020. The lesions showed progression on January 27, 2020 (b). The lesions on a chest CT scan were smaller by January 30, 2020 (c). The lesions were absorbed then before February 22, 2020 (d). This patient was discharged 4 days later

Prognosis

Among the 30 patients with available follow-up on CT, 8 showed apparent absorption during follow-up (Table 3, Figs. 3 and 4) and were discharged from the hospital. Six patients are still receiving treatment in the intensive care unit, and 28 are still receiving treatment in general wards. Eighty percent of the ICU patients were in the progressive stage of the disease. On the contrary, 75% of the discharged patients were in the early stage of the disease. Four (80%) ICU patients had multiple lesions and the distribution of the lesions involved both the subpleural area and parenchyma (Figs. 2c, d and 5), while only 2 (25%) of the discharged patients had both subpleural involvement and centro-parenchymal involvement. Three (60%) ICU patients had scattered lesions, with the primary location of lesions in discharged patients primarily in the lower lobe. Three (60%) ICU patients and 2 (25%) discharged patients had 5 lobes involved, respectively. Three (60%) ICU patients and 3 (37.5%) discharged patients had GGO with reticular and/or interlobular septal thickening/consolidation, respectively. ICU patients had significantly higher scores in the right upper lobe, right middle lobe, and right lower lobe and a higher total score.

Table 3.

CT patterns between ICU and discharged patients on initial CT scan

| CT patterns | ICU (5) | Discharged (8) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage | ||

| Early stage | 1 (20%) | 6 (75%) |

| Progressive stage | 4 (80%) | 2 (25%) |

| Absorption period | 0 | 0 |

| Lesion number | ||

| Single | 1 (20%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Double | 0 | 1 (12.5%) |

| Multiple | 4 (80%) | 6 (75%) |

| Lesion distribution | ||

| Subpleural | 1 (20%) | 6 (75%) |

| Centro-parenchymal | 0 | 0 |

| Both subpleural and centro-parenchymal | 4 (80%) | 2 (25%) |

| Initial location of lesions | ||

| Upper lobe | 1 (20%) | 2 (25%) |

| Middle lobe | 0 | 0 |

| Lower lobe | 1 (20%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Scattered distribution | 3 (60%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Number of lobes involved | ||

| 1 | 0 | 1 (12.5%) |

| 2 | 1 (20%) | 2 (25%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (12.5%) |

| 4 | 1 (20%) | 2 (25%) |

| 5 | 3 (60%) | 2 (25%) |

| Lesion patterns | ||

| Pure ground-glass opacity | 2 (40%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| GGO with reticular and/or interlobular septal thickening | 1 (20%) | 2 (25%) |

| GGO with consolidation | 2 (40%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Cavitation | 0 | 0 |

| CT score of every lobe | ||

| Right upper lobe | 1 ± 1 | 3 ± 1* |

| Right middle lobe | 1 ± 1 | 3 ± 2* |

| Right lower lobe | 1 ± 1 | 4 ± 2* |

| Left upper lobe | 1 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 |

| Left lower lobe | 1 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 |

| Total score | 5 ± 3 | 15 ± 8* |

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (minimum–maximum). *Mann-Whitney U test showed statistical difference in the right upper lobe, right middle lobe, right lower lobe, and total score between the discharged patients and ICU patients

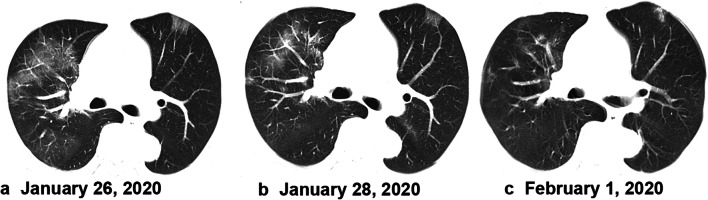

Fig. 4.

A 55-year-old man, who was a local resident of Wuhan, presented with cough and fever. Fever was accompanied by dizziness, headache, chest tightness, shortness of breath, and diarrhea. Axial unenhanced chest CT showed multiple small patchy ground-glass lesions bilaterally upon hospital admission on January 26, 2020 (a). After treatment (b, c), the lesions on chest CT showed a gradual absorption on January 28, 2020, and February 1, 2020. This patient was discharged 5 days later without clinical symptoms

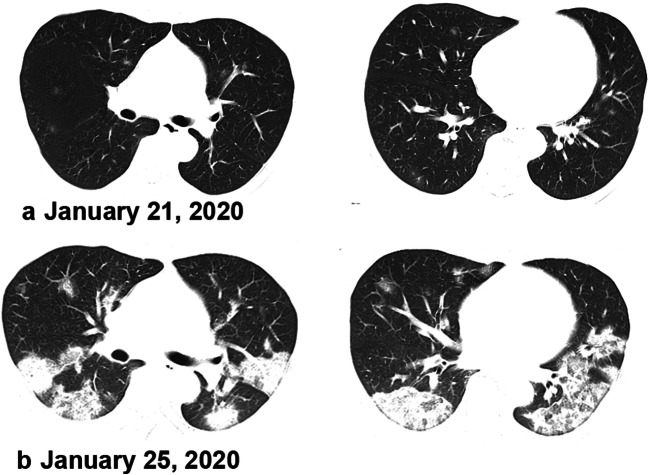

Fig. 5.

A 45-year-old man, who was a local resident of Wuhan and who had a history of exposure, presented with fever, cough, expectorating yellow phlegm, stuffy nose, runny nose, headache, and obvious muscle aches. CT scan revealed multiple sparse patchy ground-glass lesions in the subpleural area and parenchyma bilaterally upon hospital admission on January 21, 2020. The patient was admitted into an intensive care unit. CT revealed obvious progression of the disease on January 25, 2020

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that chest CT can play a crucial role in early diagnosis of COVID-19, especially in patients with a negative RT-PCR. The present study showed that all 10 patients with a negative first RT-PCR displayed typical CT manifestations at their first CT examination.

Although the specificity of the RT-PCR test is high, its accuracy largely depends on the quality of sampling. In addition, the relatively long detection time may not be adaptable to the clinical workflow and medical decision-making during an outbreak. Our study indicated that patients with a positive CT and a negative RT-PCR should be included in isolation treatment, which may be helpful in controlling the source of infection as soon as possible.

The CT imaging features of COVID-19 pneumonia are not really specific when compared with both H1N1 and SARS [8, 9]. Multifocal, bilateral ground-glass opacities, with a peripheral subpleural distribution, were found in most of our patients, in accordance with previous studies [10–14].

Beyond diagnosis, the imaging characteristics of progressive lesions on CT may help determine the prognosis. The lesions in 8 patients were decreasing in size and they were discharged from the hospital during follow-up. Five were receiving intensive care at the time of the study. Eighty percent of the ICU patients were in the progressive stage of the disease at their initial appearance, while most of the discharged patients were in the early stage at their first CT scan. CT is helpful in monitoring disease progression and evaluating the effectiveness of treatment. In addition, our study found that lesion involvement and distribution may be used as indicators for subsequent outcomes: the discharged patients showed fewer lobes involved and lesions mainly located in the subpleural area and lower lobe, while the ICU patients seemed to have more lobes involved and a scattered distribution of lesions. This is consistent with the results of Huang et al [15]. Pure GGO may be associated with a better outcome, while more lobe involvement and a scattered distribution should alert clinicians to a worse prognosis.

This study had several limitations that should be mentioned. The sample size was small. In addition, the present results were from 5-mm-thick slices, which may have misdiagnosed some subtle findings, such as tiny pulmonary nodules.

In conclusion, CT imaging is valuable in the early diagnosis of COVID-19 disease, with a special interest in symptomatic patients with a negative RT-PCR, which can efficiently screen for symptomatic COVID-19 patients in a timely manner. CT is also useful for monitoring follow-up. Early CT features may have a prognostic value. Whether a given treatment is beneficial could also be assessed with chest CT.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

2019 novel coronavirus

- CT

Computed tomography

- GGO

Ground-glass opacity

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- RT-PCR

Real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Funding information

This work was supported by the Key R & D plan of Hainan Province (ZDYF (XGFY) 2020001); Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [818MS124]; National Nature Science Foundation of China [grant number 81971602, 81760308, 81801684, 81871346]; the Program of Hainan Association for Science and Technology Plans to Youth R & D Innovation [QCXM201919].

Compliance with ethical standards

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Prof. Feng Chen.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Statistics and biometry

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Study subjects or cohorts overlap

No study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported before.

Methodology

• retrospective

• cross-sectional study

• performed at one institution

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hui Juan Chen and Jie Qiu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H et al (2020) Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 10.1148/radiol.2020200642:200642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J et al (2020) Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 10.1148/radiol.2020200432:200432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kim H, Hong H, Yoon SH (2020) Diagnostic performance of CT and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for coronavirus disease 2019: a meta-analysis. Radiology. 10.1148/radiol.2020201343:201343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Long C, Xu H, Shen Q, et al. Diagnosis of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): rRT-PCR or CT? Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108961. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J (2020) Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 10.1148/radiol.2020200343:200343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Franquet T. Imaging of pulmonary viral pneumonia. Radiology. 2011;260:18–39. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11092149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YC, Yu CJ, Chang SC, et al. Pulmonary sequelae in convalescent patients after severe acute respiratory syndrome: evaluation with thin-section CT. Radiology. 2005;236:1067–1075. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2363040958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan Y, Tao XF, Shi YX, Liu SY, Chen JQ. Initial HRCT findings of novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2012;6:e114–e119. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong KT, Antonio GE, Hui DS, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: thin-section computed tomography features, temporal changes, and clinicoradiologic correlation during the convalescent period. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:790–795. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song F, Shi N, Shan F, et al. Emerging coronavirus 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295:210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295:202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Z, Guo D, Li C et al (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019: initial chest CT findings. Eur Radiol. 10.1007/s00330-020-06816-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Li K, Fang Y, Li W et al (2020) CT image visual quantitative evaluation and clinical classification of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Eur Radiol. 10.1007/s00330-020-06817-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kim H (2020) Outbreak of novel coronavirus (COVID-19): what is the role of radiologists? Eur Radiol. 10.1007/s00330-020-06748-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]