The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has resulted in more than 4.3 M infections and 297,000 deaths worldwide [1]. It has placed an unprecedented demand on healthcare and overwhelmed the capacity of critical care services in some countries. The manifestations of COVID-19 vary from fever and mild upper respiratory tract symptoms to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multiple organ failure resulting in death [2]. Worsening disease may be driven by increased viral load and hyper-inflammation in addition to increasing age and co-morbidities [2]. Capitalising on this knowledge, several trials are underway testing the efficacy of anti-viral agents, anti-malarial agents, immune modulators, and angiotensin receptor blockers.

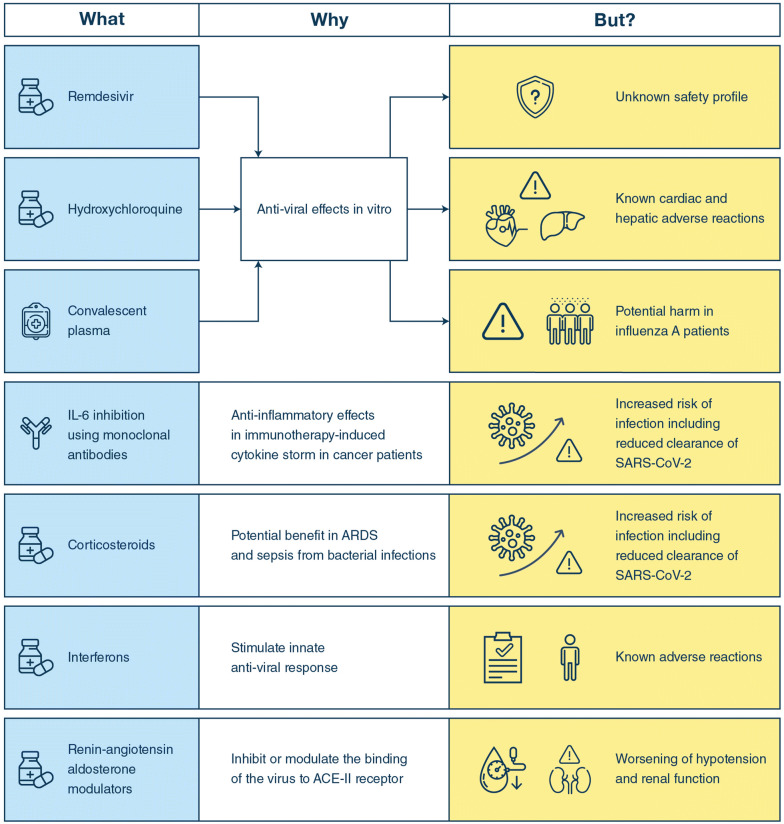

Currently, there are no approved treatments for COVID-19, and care is therefore supportive. Some patients have been treated off-label or in compassionate use programs with agents having potential antiviral and/or immunomodulatory actions (Fig. 1) [3]. For now, a few of these agents have been assessed in randomized clinical trials (RCT) but none in RCTs with the quality to assess the balance between benefits and harms [4, 5]. In addition, there are observational studies of the use of remdesivir [6], hydroxychloroquine [7] and convalescent plasma [8] in patients with COVID-19, but they have major methodological flaws. The publication of these results in high impact journals combined with mainstream and social media attention and well-intentioned, but misguided physician enthusiasm, has meant a rapid uptake of unproven interventions in several countries. Researchers have expressed concerns about the endorsement of such therapies by prominent political leaders and governments [9, 10].

Fig. 1.

Potential beneits and harms of interventions used in patients with COVID-19

In this background, the key question is if these drugs provide real benefit to patients. The question is particularly important in the critically ill COVID-19 patients because they have more at stake; benefit from the interventions may improve their survival and quality of life—harm may do the opposite.

Indirect evidence from other viral respiratory infections

The development of treatments for viral respiratory infections has been a very challenging process despite decades of research into the viruses and the host response. While remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine may have in vitro effects against SARS-CoV-2 [3], they were not developed for this. The failure of remdesivir in Ebola virus disease [11], for which it was developed, and the modest effects of antivirals in patients with influenza or respiratory syncytial virus makes it less likely that remdesivir or hydroxychloroquine will benefit patients with COVID-19. While the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial allegedly found shorter time to recovery as compared to placebo in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 as announced by a press release [12], we need to see the full trial report, including the methodological details, effects on patient-important outcomes and adverse effect, to understand these results. In particular as a fully published similar trial from China found no obvious benefit of remdesivir in these patients [13].

The case may be different for convalescent plasma as this by concept is specific against SARS-CoV-2. Again, data from influenza should dampen our expectations. In a placebo-controlled RCT, the use of anti-influenza hyperimmune intravenous immunoglobulin (hIVIG) provided no overall benefit for adults hospitalised with influenza infection [14]. In that trial, there may have been an interaction in the intervention effect by the type of influenza; those with influenza A may have been harmed from hIVIG while those with influenza B may have benefited. The latter observation shows the complexity and risk of the use of untested interventions in severe viral disease no matter how good the a priori rationale appears.

Indirect evidence from ARDS and sepsis

Similarly, in ARDS and sepsis the development of therapeutic interventions has been challenging. While the case has been built for the use of inhibitors of the ‘cytokine storm’, which is believed to drive worse outcomes in COVID-19, such strategies have failed in previous trials of various inflammatory modulators. And some of these modulators may have harmed patients [15]. While the nonspecific anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids may offer some benefit in patients with ARDS [16] and appear to benefit those with sepsis [17], most of these patients have bacterial infections and receive appropriate antibiotic therapy. As noted above, there is no effective antiviral agent against SARS-CoV-2. The obvious risk of using steroids in patients with COVID-19 is the suppression of the immune system, which may be the patient’s only defense against the virus. In contrast, interferon-beta may stimulate the innate anti-viral response, and interferon-beta-1a was recently tested in non-COVID-19 ARDS because of proposed effects on the vascular leakage [18]. The results of the latter trial were neutral both regarding efficacy and adverse effects, but interferon-beta-1a has multiple registered adverse effects when given for other indications.

Lessons from the use of low-level-evidence interventions in other critically ill patients

Unfortunately, the situation described above is not unique in critical care; many interventions administered to critically ill patients have been based on pathophysiological reasoning of expected benefit with less focus on adverse effects. Thus, many interventions in critical care have been shown to offer no benefit or result in harm when finally tested in RCTs [19]. The risk of harm from interventions may be higher when the adverse reaction appears indistinguishable from the natural history of the disease as it was the case for hydroxyethyl starch and kidney injury in patients with sepsis [20]. Clearly, this risk is also present for patients with COVID-19. While we still have very limited understanding of the pathophysiology, it is obvious that many of these patients develop the severe complications seen in other critically ill patients including brain, circulatory, hepatic and kidney failure and thromboembolic events. It will be very difficult, if not impossible, to determine if these severe complications arise primarily from the disease or from severe adverse reactions to off-label interventions used in patients with COVID-19.

Summing all this up, the net benefit is far from certain for all the therapeutic agents now used off-label or in compassionate use programs against SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, and the risk of harm is high. The testing of these interventions in large, multi-center, randomized trials with high internal and external validity, is not only a scientific necessity, but also an ethical and a moral imperative. The setting of an RCT protects the patients through the rigorous monitoring and handling of serious adverse events and helps future patients and society by producing unbiased results on the delicate balance between the benefits and harms.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

AP is the Sponsor of the COVID STEROID trial (NCT04348305), which is funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and supported by Pfizer Denmark. BK is site investigator for the SOLIDARITY trial for Apollo Hospitals, Chennai and the country PI for the Lessening Organ dysfunction with VITamin C in Sepsis trial (LOVIT India).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.(2020) Coronavirus resources center. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed 14 May 2020

- 2.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS, China Medical Treatment Expert Group for C Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borba MGS, Val FFA, Sampaio VS, Alexandre MAA, Melo GC, Brito M, Mourao MPG, Brito-Sousa JD, Baia-da-Silva D, Guerra MVF, Hajjar LA, Pinto RC, Balieiro AAS, Pacheco AGF, Santos JDO, Jr, Naveca FG, Xavier MS, Siqueira AM, Schwarzbold A, Croda J, Nogueira ML, Romero GAS, Bassat Q, Fontes CJ, Albuquerque BC, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, Monteiro WM, Lacerda MVG, CloroCovid T. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208857. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung IF-N, Lung K-C, Tso EY-K, Liu R, Chung TW-H, Chu M-Y, Ng Y-Y, Lo J, Chan J, Tam AR, Shum H-P, Chan V, Wu AK-L, Sin K-M, Leung W-S, Law W-L, Lung DC, Sin S, Yeung P, Yip CC-Y, Zhang RR, Fung AY-F, Yan EY-W, Leung K-H, Ip JD, Chu AW-H, Chan W-M, Ng AC-K, Lee R, Fung K, Yeung A, Wu T-C, Chan JW-M, Yan W-W, Chan W-M, Chan JF-W, Lie AK-W, Tsang OT-Y, Cheng VC-C, Que T-L, Lau C-S, Chan K-H, To KK-W, Yuen K-Y. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. The Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G, Asperges E, Castagna A, Feldt T, Green G, Green ML, Lescure FX, Nicastri E, Oda R, Yo K, Quiros-Roldan E, Studemeister A, Redinski J, Ahmed S, Bernett J, Chelliah D, Chen D, Chihara S, Cohen SH, Cunningham J, D'Arminio Monforte A, Ismail S, Kato H, Lapadula G, L'Her E, Maeno T, Majumder S, Massari M, Mora-Rillo M, Mutoh Y, Nguyen D, Verweij E, Zoufaly A, Osinusi AO, DeZure A, Zhao Y, Zhong L, Chokkalingam A, Elboudwarej E, Telep L, Timbs L, Henne I, Sellers S, Cao H, Tan SK, Winterbourne L, Desai P, Mera R, Gaggar A, Myers RP, Brainard DM, Childs R, Flanigan T. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Courjon J, Giordanengo V, Vieira VE, Dupont HT, Honore S, Colson P, Chabriere E, La Scola B, Rolain JM, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;10:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, Yang Y, Li J, Yuan J, Wang F, Li D, Yang M, Xing L, Wei J, Xiao H, Yang Y, Qu J, Qing L, Chen L, Xu Z, Peng L, Li Y, Zheng H, Chen F, Huang K, Jiang Y, Liu D, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Liu L. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1582–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathi S, Ish P, Kalantri A, Kalantri S. Hydroxychloroquine prophylaxis for COVID-19 contacts in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30313-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim AHJ, Sparks JA, Liew JW, Putman MS, Berenbaum F, Duarte-Garcia A, Graef ER, Korsten P, Sattui SE, Sirotich E, Ugarte-Gil MF, Webb K, Grainger R, Alliancedagger C-GR. A rush to judgment? Rapid reporting and dissemination of results and its consequences regarding the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT, Jr, Tshiani Mbaya O, Proschan M, Mukadi D, LusakibanzaManzo M, Nzolo D, TshombaOloma A, Ibanda A, Ali R, Coulibaly S, Levine AC, Grais R, Diaz J, Lane HC, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, PALM Writing Group. Sivahera B, Camara M, Kojan R, Walker R, Dighero-Kemp B, Cao H, Mukumbayi P, Mbala-Kingebeni P, Ahuka S, Albert S, Bonnett T, Crozier I, Duvenhage M, Proffitt C, Teitelbaum M, Moench T, Aboulhab J, Barrett K, Cahill K, Cone K, Eckes R, Hensley L, Herpin B, Higgs E, Ledgerwood J, Pierson J, Smolskis M, Sow Y, Tierney J, Sivapalasingam S, Holman W, Gettinger N, Vallee D, Nordwall J, PALM Consortium Study Team A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(2020) NIH clinical trial shows remdesivir accelerates recovery from advanced COVID-19. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-clinical-trial-shows-remdesivir-accelerates-recovery-advanced-covid-19. Accessed 14 May 2020

- 13.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, Fu S, Gao L, Cheng Z, Lu Q, Hu Y, Luo G, Wang K, Lu Y, Li H, Wang S, Ruan S, Yang C, Mei C, Wang Y, Ding D, Wu F, Tang X, Ye X, Ye Y, Liu B, Yang J, Yin W, Wang A, Fan G, Zhou F, Liu Z, Gu X, Xu J, Shang L, Zhang Y, Cao L, Guo T, Wan Y, Qin H, Jiang Y, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Cao B, Wang C. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. The Lancet. 2020;395:1521–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey RT, Jr, Fernandez-Cruz E, Markowitz N, Pett S, Babiker AG, Wentworth D, Khurana S, Engen N, Gordin F, Jain MK, Kan V, Polizzotto MN, Riska P, Ruxrungtham K, Temesgen Z, Lundgren J, Beigel JH, Lane HC, Neaton JD, INSIGHT FLU-IVIG Study Group Anti-influenza hyperimmune intravenous immunoglobulin for adults with influenza A or B infection (FLU-IVIG): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:951–963. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30253-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher CJ, Jr, Agosti JM, Opal SM, Lowry SF, Balk RA, Sadoff JC, Abraham E, Schein RM, Benjamin E. Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein. The soluble TNF Receptor Sepsis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1697–1702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S, Levy MM, Derde L, Dzierba A, Du B, Aboodi M, Wunsch H, Cecconi M, Koh Y, Chertow DS, Maitland K, Alshamsi F, Belley-Cote E, Greco M, Laundy M, Morgan JS, Kesecioglu J, McGeer A, Mermel L, Mammen MJ, Alexander PE, Arrington A, Centofanti JE, Citerio G, Baw B, Memish ZA, Hammond N, Hayden FG, Evans L, Rhodes A. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;28:1–34. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rygard SL, Butler E, Granholm A, Moller MH, Cohen J, Finfer S, Perner A, Myburgh J, Venkatesh B, Delaney A. Low-dose corticosteroids for adult patients with septic shock: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1003–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranieri VM, Pettila V, Karvonen MK, Jalkanen J, Nightingale P, Brealey D, Mancebo J, Ferrer R, Mercat A, Patroniti N, Quintel M, Vincent JL, Okkonen M, Meziani F, Bellani G, MacCallum N, Creteur J, Kluge S, Artigas-Raventos A, Maksimow M, Piippo I, Elima K, Jalkanen S, Jalkanen M, Bellingan G, INTEREST Study Group Effect of intravenous interferon beta-1a on death and days free from mechanical ventilation among patients with moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:725–733. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perner A, Myburgh J. Ten 'short-lived' beliefs in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1703–1706. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, Tenhunen J, Klemenzson G, Aneman A, Madsen KR, Moller MH, Elkjaer JM, Poulsen LM, Bendtsen A, Winding R, Steensen M, Berezowicz P, Soe-Jensen P, Bestle M, Strand K, Wiis J, White JO, Thornberg KJ, Quist L, Nielsen J, Andersen LH, Holst LB, Thormar K, Kjaeldgaard AL, Fabritius ML, Mondrup F, Pott FC, Moller TP, Winkel P, Wetterslev J. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer's acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:124–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]