Abstract

This article examines the coping strategies of individuals during the confinement in France using a sensemaking lens. We draw on two studies consisting of 85 qualitative surveys followed by a diary in which 20 individuals wrote about their experiences during the first three weeks of the confinement. We employ an interpretative phenomenological approach to analyse the data. The findings reveal two patterns in the ways men and women cope with their experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The first pattern shows intensification of gender performativity manifested in the reproduction of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ reactions to the crisis. The second pattern detects a tendency towards a gradual deflection from gender performances through mental improvisations that foster new awareness of the crisis presenting an opportunity to transcend traditional gender roles. Our study highlights some potential emancipatory implications the COVID‐19 crisis may have for the practices of ‘doing gender’ and perceptions of work–life balance therefore instigating a transition towards more egalitarian households.

Keywords: COVID‐19, gender performativity, mental improvisations, minimal organizations, sensemaking

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic of 2020 — and the compulsory regime of domestic confinement in many countries across the world — has led millions of families to face unprecedented and challenging circumstances. No one was adequately prepared to not only drastically change professional and private routines but also continue as if it was ‘business as usual’. The organizational literature tends to describe such occurrences of discontinuity as ‘disruptions’ — for instance, large‐scale alterations of modi operandi that catch actors off guard and radically transform existing orders (e.g., Gustafsson, Gillespi, Searle, & Dietz, 2020). However, in these accounts potentially disruptive events also have a degree of manageability, as actors eventually attempt to make sense of a new situation and adapt to it (Meyer, 1982). These two sets of reactions are intrinsically intertwined, since sensemaking responses dictate the choices of subsequent actions and adaptations.

To this end, various streams in the literature — from entrepreneurship to crisis management — treat disruptions as irrevocable changes that alter or eliminate taken‐for‐granted practices and relationships. This assumption of irrevocability stems from sensemaking convergence — for instance, sooner or later everyone (more or less) adapts, in the face of de‐legitimation (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), obsolescence (McGahan, 2004) or inefficiency (Hannah & Freeman, 1977). But in practice, full convergence rarely takes place. Many organizations and individuals resist change in their patterns of thinking and their actions, amidst a storm of disruption and even to their detriment. A case in point is inter‐gender relations and the related resistance to embrace transformative disruption (McCarthy & Moon, 2018). This predicament also marks family life which is vividly demonstrated in Force Majeure, a Swedish movie that tells the story of an idyllic, family ski holiday that is interrupted by a catastrophic reckoning. The main protagonists are confronted with the dilemma of how to make sense of their actions amidst a complete break from certainty. An avalanche of five seconds is enough to shatter all behavioural conventions and to reveal inconvenient truths in a seemingly exemplary, modern marriage. What comes after the avalanche is not a transformation of behavioural patterns but rather a desperate attempt to restore appearances, reinforce routines and resume role‐playing. The characters employ the full weaponry of performativity to keep their predispositions intact.

Karl Weick (2009) observed and theorized the same rigidities in sensemaking through his studies of individual interactions in disrupted organizational settings. Drawing on his insights, we argue that a specific disruption can only be deemed transformative or detrimental after the variability of individual responses to the unforeseen and the unexpected — or what we term ‘coping strategies’ — is understood. We address this claim by investigating and critically evaluating the coping strategies that individuals developed in the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the COVID‐19 outbreak and the subsequent — and compulsory — order of domestic confinement. Furthermore, we also interrogate the role of gender in the formulation and articulation of crisis management responses under conditions of mandatory domesticity. Finally, we explore whether the COVID‐19 crisis could disrupt conventional household arrangements and clear a path for a broader and bolder feminist transformation of inter‐gender relations in the private sphere of co‐habitation.

To address these goals, we first present the dynamics of role‐playing and performativity in high‐stress situations. Drawing from the work of Karl Weick (1993) on the Mann Gulch disaster, we investigate the collapse of sensemaking within the context of household organization. We then present the methodology and main findings, followed by a discussion of the main insights and implications for future research in the area of gender equality.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Minimal organizations and the collapse of sensemaking

In moments of catastrophic reckoning, what is broken in a society — including the institutions of that society — is often revealed by way of haunting images or heartbreaking stories. A sinking Titanic surrounded by half‐empty boats carrying first‐class passengers to safety, or a worry‐worn migrant mother holding two hungry children during the Great Depression are profound images that depict the unfairness and frailty of the human condition. In the social sciences, we make sense of such daunting realities by employing macro‐level vocabulary to describe collective moral failures, to generalize the implications of large‐scale disasters for political and socioeconomic systems (e.g., Collapse by Jared Diamond, 2005), and to comprehend their perseverance. However, according to Graeber and Wengrow (2018), actors in these types of systems — before, during and after they crumble — experienced the most pain:

at the small scale — at the level of gender relations, age groups, and domestic servitude — the kind of relationships that contain at once the greatest intimacy and the deepest forms of structural violence. If we really want to understand how it first became acceptable for some to turn wealth into power, and for others to end up being told their needs and lives don’t count, it is here that we should look.

These relationships constitute what Karl Weick (1993) deemed ‘minimal organizations’ (p. 632), which are characterized by established routines, the division of labour, behavioural norms and symbolic order. At a more personal level, disasters rip off the veil of (often wilful) ignorance concerning choices made in household roles. Disasters also allow questioning of rules that otherwise guide and inform individual behaviours under the comparatively ‘normal’ conditions of daily life.

Minimal organizations — like other established structures of relations — are susceptible to sudden losses of meaning. The literature describes such losses as fundamental surprises, inconceivable or incomprehensible events (Weick, 1993) and exogenous shocks (Cattani, Ferriani, & Lanza, 2017). What all these situations have in common is some degree of unfathomability and, according to Weick (1993), the ‘perceiver’s inability to rebuild some sense of what is happening’ (p. 633). He borrowed the philosophical concept of ‘cosmology’ to describe how individuals could come to terms with what initially escaped or distorted their sensemaking by developing or imposing a temporary perspective of order over the perceived chaos and acting as if its unfolding were ‘normal’. Weick (1993) emphasized that these everyday cosmologies remain susceptible to disruption when people suddenly and deeply feel that the universe is no longer a rational, orderly system’ (p. 633). What makes this type of disruption so shattering is that ‘both the sense of what is occurring and the means to rebuild that sense collapse together’ (p. 633). In the case of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the fear of losing a temporary perspective of order is not only what drives household members in their response to the crisis but also what sustains them in their struggle to avoid the collapse of an intelligible perception of the world.

Furthermore, the rationality of formulating coping strategies in such situations often remains highly contextual, in that it is motivated by perceived levels of appropriateness and by a respect for established cultural and social norms. As argued by Weick (1993), since ‘social actors need to create and maintain intersubjectively binding normative structures’ (p. 634), individuals impose constraints on their sensemaking efforts as they navigate the stormy waters of a burgeoning disaster, and they curb impulses to break free from learnt models of behaviour. In other words, the more our responses to crises rely on contextual rationality, the more likely our coping strategies will include an impersonation of our appropriate selves, and a reproduction of the status quo in the more problematic aspects of interactions and exchanges with others. In a minimal organization like a household, responses to a crisis like COVID‐19 may translate into ‘doing gender’, which has already appeared in the behavioural patterns of political leaders reacting to the global pandemic.1

Coupling Weick’s insights with recent work on moral reflexivity (Shadnam, 2020), we argue that the moment of formulating and enacting a response to the conditions of mandatory confinement is the moment of choosing who to be with respect to the demanding situation. The mode and form of such self‐presentation depend on one’s sensitivity to perceived contextual demands and the repertoire of symbolic resources that are available to the individual for conducting her response to the crisis in the way that surpasses the dictates of customary sensemaking.

2.2. Role improvisations as a resilience to crisis

Given that we present a coping strategy of an individual in the state of emergency as a quest to choose who to be, a salient set of symbolic resources that feed into this quest are identities. Identities constitute an integral part of evaluative categories offered by cultural norms (Callero, Howard, & Piliavin, 1987; Hitlin, 2008). However, identities are often vague and incomplete narratives that individuals tailor to author their own self‐concept (Clarke, Brown, & Hailey, 2009). From a sensemaking perspective, self‐concept is a system that is operationally closed yet sensitive to environmental triggers, as individuals continuously work to reduce complexity — especially in extreme situations (Weick, 1993). In this sense, a force majeure coping strategy can be taken on when individuals attempt to reduce the complexity of a disturbance that requires a quick definition of the self in relation to challenging circumstances.

Furthermore, previous research on sensemaking during disasters has demonstrated that individuals either stubbornly stick to customary identities that sustain a temporary perspective of order or opt for new ones that have a better fit with a changing reality (Gladwell, 2008). To deal with identity choices, individuals must be able to justify and defend their choices in front of others — or according to Weick (1993), ‘people try to make things rationally accountable to themselves and to others’ (p. 635).

Consequently, when individuals disclose their identity choices in demanding circumstances, they simultaneously search for justifications. Therefore, a set of available justifications is also a set of symbolic resources, with significant conditioning effects on the reflexivity and ability of individuals to deviate from normative expectations related to prescribed functions in a (minimal) organization (Shadnam, 2020).

According to Weick (1993), as a crisis unfolds all recognizable patterns of sensemaking break. An important source of resilience against total collapse may emerge from reconstituting conventional role systems and engaging in role improvisations. Deliberate abandonment of the learnt and the known helps avert the panic that paralyses cohesive action and that leads to organizational disintegration. Weick (1993) explained that as role structures lose their meaning in the face of persistent challenges, people endeavour to make sense of what is happening. As a result, individuals increase and intensify attentiveness to their own actions, whereby a more acute‐level self‐awareness creates the conditions that enable them to break free from prescriptive and performative ways of sensemaking. As stated earlier, these improvisations are bounded, since the choice of who to be in times of crisis remains constrained — and defined — by available justifications that render them sensible.

In a traditional household, the most common sets of justifications that render behaviour ‘sensible’ in the eyes of individuals, as well as the eyes of others, are gender‐centric. Thus, we investigate how gender influences sensemaking in a time of confinement and what improvisational responses around gender roles emerge in a deepening crisis.

3. METHODS

Two qualitative studies were employed to examine the ways in which individuals experienced and coped with the period of confinement associated with the COVID‐19 crisis in France. Study 1 consisted of 85 participants who completed 14, mostly open‐ended, questions concerning their perceptions and emotions during confinement. The qualitative survey identified themes related to the experiences of the participants. In Study 2, a qualitative diary study was conducted with 20 individuals — ten females and ten males — who wrote about their experiences on a daily basis for three weeks. Diary studies are increasingly being used in management and organizational psychology (van Eerde, Holman, & Totterdell, 2005). As this method is often employed to investigate stress, emotions and the work–home interface (Bono, Foldes, Vinson, & Muros, 2007; Butler, Grzywacz, Bass, & Linney, 2005; Ilies, Schwind, & Heller, 2007; Tschan, Rochat, & Zapf, 2005), a diary study was well‐suited to interrogate issues of interest during the COVID‐19 crisis. The diary method also allowed collection of data in the natural context of individuals, capturing ‘life as it [was] lived’ (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003, p. 597). Both Study 1 and 2 afforded insights into lived experiences of individuals during confinement in France.

3.1. Recruitment and sample

A convenience and snowball sampling technique was employed to recruit participants for both studies. Individuals self‐selected, which was an appropriate approach as diary completion requires a high level of commitment (Symon, 1998). For Study 1, the final sample included 85 working adults of which 55 per cent identified as female. The average age was 41 years, with a range in age of 30–64 years. All participants were living and working in France. Participants were employed in a variety of sectors including health care, retail, administration, customer services and education. For Study 2, the final sample included ten individuals identifying as female and ten identifying as male. The average age was 41 years.

3.2. Instruments and approach

To ensure consistency and realism of our data, we used a sequential exploratory approach. The qualitative survey (Study 1) identified salient themes, which were then built upon in the diary study (Study 2). The survey utilized a qualitative approach, which helped define and investigate variation in the population (Jansen, 2010). Previous research has established the usefulness of the qualitative survey in capturing lived experiences of individuals (Fink, 2003). The aim of the qualitative survey is not to produce frequencies or descriptive statistics but rather to determine the diversity of accounts on some topic of interest within a given population. In this case study, the qualitative survey captured the experiences of individuals during the time of confinement that resulted from the COVID‐19 crisis. Participants answered 14, mostly open‐ended, essay questions. A link to the anonymized online survey was sent to potential respondents by email. The survey included questions about feelings and emotions, encountered difficulties, and potential positive aspects of confinement, identity and work–life balance. A final, open‐ended question allowed participants to share any other information they felt pertinent to the case. The survey was administered in French, and back‐and‐forth translation was applied in translating the data into English.

The diary study included daily entries written by 20 individuals during confinement. They were asked to write each evening about their experiences of confinement on that day. A relatively long period of time (i.e., three weeks, including weekends) and a relatively small sample (i.e., 20 individuals) was chosen to capture how the experiences of the participants evolved over time. Our approach was in line with previous research, which has favoured a prolonged, small sample approach for tracking changes over time (Fuller et al., 2003). Participants were told that they could either provide handwritten entries — which were digitized by the research team at the end of the study — or typed responses — which were sent by email to the research team. As Internet use increased considerably during the COVID‐19 crisis and led to connection problems for some, the option of a paper‐and‐pencil diary was a useful way to mitigate online challenges. The diary study sought to track experiences, feelings, perceptions and attitudes over time. All participants received a daily reminder with some questions to guide their thinking. These guiding questions were not identical each day but rather covered the same topics using slightly different wordings. A semi‐freeform diary was employed; guiding questions covered the topics under study but left space for other themes to emerge. The participants were told they could contact the research team at any time by email or telephone in case of any questions. All recruited participants completed their daily diary logs throughout the entire study period (i.e., 21 days). We sensed a strong motivation to participate in the respondents, which may have been positively influenced by the increase in free time for most participants during confinement. While no monetary compensation was provided for participation, we acknowledge a selection bias — for instance, we do not know in what ways responses of individuals who declined to participate would have differed from those who accepted the invitation.

At the end of the three‐week period, the research team contacted each participant for a short interview over Skype or by telephone to ensure that the interpretations of the diary data by the research team aligned with the intentions of the participants. With an average duration of 35 minutes, these interviews helped clarify any ambiguities and were, thus, included in the analysis. These interactions also offered a chance for a shared reflexivity and a validation of the findings (Bauer & Gaskell, 2000), as well as a time for the research team to arrive at a communicative validation of the findings. Thus, this step provided a greater level of confidence in the analysis and findings. Table 1 provides a description of the two data sources used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Description of data sources

| Data source | Number of participants | Number of pages of analysed text | Content | Time period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey study | 85 | 58 | 14 questions to identify themes to explore further | 16/03/2020–23/03/2020 |

| Diary entries | 20 | 512 | Semi‐structured approach with questions to guide reflection based on the themes identified in survey study | 16/03/2020–12/04/2020 |

| Interviews at the end of diary study | 20 | 90 | Individual interview with each participant to ask for clarification where necessary and to ensure that the interpretations of the research team of the diary data aligned with the way the participants’ intentions | 11/04/2020–12/04/2020 |

4. ANALYSIS

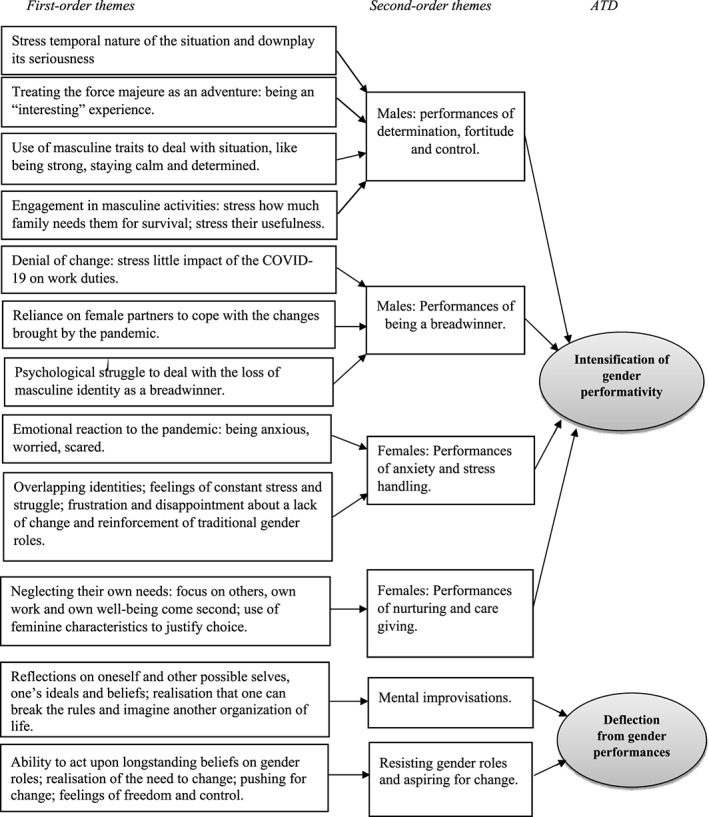

The research team analysed the qualitative survey data by hand using content analysis (Stemler, 2001). While frequency counting was employed, the team was mindful that words do have multiple meanings (Krippendorff, 2018). An interpretative phenomenological approach was applied to the diary study data to capture — and make sense of — personal perceptions and experiences of the participants (Smith & Shinebourne, 2012). Following Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (2013), analysis was conducted in three, interrelated steps in an iterative manner. The research team went back and forth between the various sources of data, including diary entries, short interviews, surveys and coding schema. Figure 1 illustrates how the analysis evolved from first‐order themes to broader categories and theoretical dimensions.

FIGURE 1.

Data structure [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

During the first step of the analysis, each member of the research team read the diaries, transcripts and survey responses several times to get a sense of the data. The data were coded using open coding (Locke, 2001) with a focus on the lived experiences and sensemaking process of the participants. In addition, a contextually sensitive approach was adopted whereby the wider social context was considered during the interpretation of the findings. The coding schema evolved as new codes were added, new sub‐codes were created and existing codes were merged. First‐order codes appear on the left in Figure 1. Next, the research team focused on the connections between codes and the identification of higher‐order conceptual codes. At this point, the analysis shifted away from a descriptive formulation of first‐order codes — whereby the exact words of the participants were used to closely align with the perspectives of the participants — and proceeded towards a higher level of abstraction through the creation of meaningful themes. The ways in which the participants made sense of their subjective experiences during the COVID‐19 crisis were then linked to the notion of gender performativity. These second‐order themes are found in the middle in Figure 1. In the third and final step of analysis, the research team returned to the literature to further investigate emergent themes and to determine whether any key constructs were missed. The final, aggregated set of theoretical dimensions is found on the right in Figure 1.

5. FINDINGS

The findings demonstrate that the COVID‐19 crisis was a catalyst in gender‐centric sensemaking as individuals sought to cope with the crisis. Two distinct patterns emerged from the data. On the one hand, gender performativity intensified as manifested in the reproduction of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ reactions to the crisis. Both female and male respondents engaged in performative behaviours that reinforced conventional gender roles. On the other hand, the COVID‐19 crisis also augmented self‐awareness and attentiveness to the traditional gender role system and, in some cases, offered an opportunity for its reconstruction or dismantlement. Both genders highlighted that the crisis allowed them to act upon long‐standing beliefs and wishes to change their work–life balance, as well as adopt more egalitarian modes of co‐habitation.

5.1. The intensification of gender performativity

Both male and female household members coped with the COVID‐19 crisis through gender performativity. On the one hand, males engaged in performances of determination, strength and control as breadwinner of the household. On the other hand, females demonstrated both performances of anxiety and sensitivity to stress handling, and performances of nurturing and caregiving. These themes are elaborated through selected, illustrative quotes.

5.1.1. Performances of determination, fortitude and control

Male participants tended to downplay the seriousness of the situation and stressed its temporary nature. Many of the male respondents constructed their sensemaking of the crisis along the following lines: ‘I can’t wait to get back to work, I’m glad this is not forever’ and ‘It’s only for a couple of months, I can’t wait that everything will get back to normal.’ In addition, male respondents used traits — such as determination and decisiveness, typically associated with masculinity — to explain how they coped with the reality of COVID‐19. As one participant during the first week of the confinement reported: ‘We just have to keep our heads cool and deal with the situation with calmness and determination.’ While only some of the male participants admitted that they were afraid and disoriented, female participants frequently reported feeling frightened, anxious and worried.

Apart from downplaying the seriousness of the COVID‐19 pandemic and highlighting its temporary nature, male respondents also reported on changes in their lives during confinement. Rather than embracing the new situation, they treated it as an adventure or an exploit, using terms such as interesting and fascinating to describe the new experiences. For example, one participant reported: ‘My wife can still work, so I’m now responsible for everything at home, doing the cooking, home‐schooling the kids, and everything. It’s an interesting experience.’ Similarly, another participant declared: ‘I’m discovering a whole new world of responsibilities at home. It is fascinating. It’s good to feel useful again.’ While expressing a positive reaction to new domestic experiences, male respondents also stressed once more that the situation was temporary and that things would go back to normal in several weeks or months. Many male participants actively used terms that highlighted the temporality of the change in role — such as ‘for the time being’, ‘for the moment’ and ‘for now’. Furthermore, the male respondents described their new household responsibilities in a masculine manner, emphasizing the difficult and effortful aspects of their helpfulness at home. For example, one male participant wrote: ‘We have complementary roles at home. I’m doing the heavy stuff in the house.’ They tended to stress their usefulness through the usual masculine activities they performed at home: ‘I realize how many things needed to be done at home. I’m finally doing these things now, which is cool.’ They also stressed how much their families needed their reassuring presence. Once more, they used terms like ‘being strong’ to show that a masculine attitude of imposing discipline would be helpful in getting through the COVID‐19 crisis. As one participant reported: ‘This requires a strong will and determination. I make sure my family complies with the guidelines of the government.’ In the same vein, another participant wrote: ‘It’s important to stick to the rules. We have to be strong and determined.’

5.1.2. Performances of being a breadwinner

Men reflected on the enforced changes in their daily activities. As one diary‐participant confessed: ‘We’ve had 10 days now and it’s increasingly difficult for me. I’ve always felt good at work; it’s an important part of me and now there is this void.’ The diary study data revealed that men found being off work increasingly difficult over time. Those men who continued working from home considered that doing so while having children around was ‘impossible’ or ‘incompatible’. They tried to reduce the impact of the confinement by behaving as if nothing changed apart from their workspace: ‘I’m working from home, but I don’t let this affect my work. I’m behind my computer as usual. I do the same hours and only have lunch with the family.’ They tended to rely on their partners to absorb the shock of confinement by employing stereotypical justifications:

She’s better with the kids, so I let her do the home schooling. It’s good this way’ and It’s more important than ever to show that I’m doing my work well, so it’s really not an option to help out at home right now. I’m earning more than my wife, so my work comes first.

Men whose professional activity had been greatly reduced or had ceased altogether struggled more psychologically and reported feelings of alienation. All the additional activities they had to engage in their household could not replace or compensate for their inability to work outside the home. As one participant reported:

I’ve noticed how important work is to me; it’s actually all I have. I feel truly lost right now. I don’t know what do to. My role is to earn money for the family and that role has been taken away from me.

5.1.3. Performances of anxious coping and stress handling

Female participants experienced confinement differently. They tended to have a more emotional reaction to the COVID‐19 crisis and frequently mentioned feeling overwhelmed, anxious, stressed and on edge. They explained that their multiple identities as professional, mother and wife now overlapped, leading to feelings of inadequacy, ineptness and failing on all fronts. One participant related such feelings most acutely: ‘I’m a bad mother, a bad wife, and a bad worker.’ Almost all female participants reported difficulty in juggling paid work and home‐schooling children. However, rather than describing new household duties in terms of being ‘impossible’ as their male counterparts did, they reported that working from home — while managing all the rest — was still ‘the ideal solution’. This was a seemingly contradictory position, as the female respondents appeared to make sense of a physically and mentally draining mix of roles as an inevitable and natural state of affairs. While female participants highlighted the normality of assuming responsibilities on multiple fronts: ‘As my work can be easily done from home, I’m not really disturbed’, they also stressed how difficult it was for them to make sense of the new situation.

As they reflected on their own household experiences, they were aware that obligatory confinement had reinforced — not tempered — traditional divisions of gender roles. One female participant conveyed this realization:

It’s been two weeks now and I kind of expected that my husband would gradually become more involved with the kids, the cooking, etc., but for some reason he seems to be pretty cool, and I’m running around as usual. I had hoped this would disrupt certain patterns at home.

Disappointment could be detected concerning desirable yet missed opportunities to change established household modi operandi in several narratives. One diary entry reflected the bitterness of losing hope for a fair division of duties:

In the beginning, I tried to stay on top of things, making sure the children are ready for their online courses and buying groceries. I also tried to support (husband) as he finds it difficult to be at home all the time without anything to do. However, it’s too much for me now; I can’t handle everything. I need my husband to support me too, but I’m the one juggling with every single bit. It’s frustrating and disappointing. I had so hoped for a change!

When a change towards an egalitarian division of the domestic burden was acknowledged, many female respondents were nevertheless sceptical that this temporary improvement would become a new norm:

It’s pretty funny, because my husband feels he’s amazing now that he does a few new things now and then, but it’s still a far cry from equal sharing. As soon as this is over, things will just continue as if nothing had ever happened.

5.1.4. Performances of nurturing and caregiving

The female participants tended to neglect their own needs when adapting to confinement, in contrast to their male partners who sought to reduce the impact of the COVID‐19 crisis on their work. Female participants also prioritized the needs of others over their own. In the third week of confinement, one female participant justified the inevitability of her self‐sacrifice in the following diary entry:

I’m the primary caregiver, so this falls on me. I cannot say this makes my life easier, but many of the tasks that need to be done are kind of fixed. I cannot reduce or remove them; I just need to do it. Cooking, cleaning, schooling, it’s impossible not to do it.

Consequently, female participants also felt antagonized in neglecting or downplaying their own needs in the new, demanding circumstances: ‘Not only my work suffers; I have absolutely no time for myself. I struggle to find the time to phone friends and family, to do sports, or simply relax.’ These female participants justified their self‐abandonment by stressing the naturalness of treating domestic errands as obvious priorities. One participant spoke quite bluntly: ‘Of course, my kids are my priority right now.’ Others pointed out that they were better prepared or naturally predisposed to carry out certain duties: ‘Someone needs to do it, and I guess it’s easier for me than for my husband to do the home‐schooling thing.’ In the same vein, one respondent directly expressed her rationalization for taking over home‐schooling: ‘Compared to my partner, it seems more natural to me to look after the kids.’

5.2. Deflecting gender performances

While there was an intensification of gender performativity resulting in the reinforcement of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ gender roles during confinement, there also was a second tendency that emerged from the survey and diary data. Some participants from both genders engaged in a deeper introspection about their predicament and started articulating less formulaic responses to the situation as confinement continued. This resulted in an expressed willingness for self‐questioning to revise traditional gender roles. Some respondents went so far as to acknowledge the need for both resistance and change in the state of their tasks and roles within their households. These strategies of deflection thus included: mental improvisations, and resisting gender roles and aspiring for change.

5.2.1. Mental improvisations

Mental improvisations took the form of reflections on the experience of alienation, which was created by a misalignment between an actualized and envisioned/aspirational self. These existential questions activated introspective sensemaking, whereby participants critically interrogated their choices, ideals and beliefs. This engagement — in an Arendtian exercise of ‘thinking without a banister’ (Arendt, 2018) — opened the way for new ‘imaginaries’ (Grünberg & Matei, 2020) that stretched from discovering the real meaning of freedom in daily life, to entertaining the idea of the world embracing a new sense of power and changing accordingly. Many participants viewed the crisis as an opportunity to follow the Nietzschean call for a re‐evaluation of all actions and values: ‘It is a necessity to take a break and take a step back.’ One male participant confessed: ‘I’m finally able to do what I’ve secretly always wanted: work at my own pace without wasting a lot of time on transportation.’ Many male participants admitted that the COVID‐19 crisis allowed them to put things in perspective and forced them to adapt to a new way of existence in which their ‘life [now] comes before their work’, and that the crisis ‘allowed them to exist without their work’. As a gradual process, male participants found confinement to be psychologically challenging in the first week, but by the second week, some allowed their sensemaking to evolve by accepting the dissolution of their masculine professional selves or downgrading the significance of this role altogether. As time passed, they adapted to the new situation and, rather than resisting, they started imagining other possible selves:

It’s day 13 today … I’m thinking about whether this situation is going to change the way society functions. Will we all go back to work, back to the rush, once this is all over? I don’t think so. I think this can be an opportunity to profoundly change the way we live and that includes myself, my own behavior, both at work and at home. I no longer want to be this absent dad who only cares about his work. I know what I no longer want, but I do not know what I want to become.

Many reflected on the long‐term effects of the pandemic and hoped to resume work with a different rhythm in the future. Having time to think led some to re‐encounter a sense of their own agency and question some taken‐for‐granted norms of domestic organization. As one male participant reported: ‘I’ve realized that our roles [within the family] are very different and that this is open to change as long as we want it.’ Although mental improvisations were more common among male participants, female respondents also highlighted that the current situation allowed them to act upon long‐standing beliefs: ‘Work–life balance has always been an important concept to me, but my work ethic has also made me work a lot during the week.’

5.2.2. Resisting gender roles and aspiring for change

Another form of deflection was observed in participants that resisted even further embeddedness and normalization of traditional gender roles in the household, and in participants that aspired for wider change. Some were aware of — and attentive to — the traditional role system and perceived the COVID‐19 crisis as an opportunity to reconstruct it for the better:

At home, I can see that things are changing. Slowly, very slowly. The presence of my partner is weird as we’re very used to his absence. However, I guess that over time this could be something positive, it could change the way we organize ourselves at home.

Both gender groups highlighted that the crisis had allowed them to act upon their long‐standing beliefs. They emphasized that the crisis had validated a perceived unfairness that perpetuated organizational routines of housekeeping. Some participants reported that they aspired for real change: ‘The confinement could lead to a real change I think. I really hope the world will become a better place and that things will change.’ Many of them had adopted a ‘now or never’ attitude; they viewed the situation as a once‐in‐a‐lifetime opportunity to push for changes in domestic, inter‐gender relations.

Participants also highlighted that they had tried to change their ways of dealing with household responsibilities, but they did so with little success. The pandemic had forced a change in domestic life that they had aspired to have but had never managed to obtain. As one participant mentioned:

It’s been years that we [the couple] try to make some structural changes to the way we balance our jobs, the kids, the household, etc. We just never succeeded. This [COVID‐19] is the push we needed.

Therefore, in at least some cases the ongoing crisis triggered and was the catalyst for resisting traditional gender roles and offered a platform for change. The diary data also revealed that aspirations for change and longing for liberation from the imperatives of gender‐centric performances had already been strengthening over time. As one female respondent confessed: ‘I’ve always felt it, wanted it, and now the time has come to make sure we rebalance things, to become who we really are deep inside.’ Finally, the newly encountered agency and perceived weakening of social control had strengthened the perception of the pandemic as a lever for gender emancipation. This sense of freedom was voiced by one of the female participants: ‘We’re very much dependent on the perception and judgment of others, our consumption, our work. Now, I feel free to make my own choices.’

Taken as a whole, our analysis not only unveiled a repertoire of individual coping strategies during confinement but also revealed their evolution over time. While normative, gender‐centric social expectations provided a sense of orientation and informed most of sensemaking at the beginning of confinement, these expectations began to disappear as the crisis progressed and as hidden tensions — that could no longer be ignored — surfaced. Some participants continued to engage in gender performances as a way of handling increasing uncertainty, and others began to deflect and unburden themselves from fulfilling social expectations in favour of improvised explorations of their new selves and visions of family life.

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the coping strategies of individuals in the situations of unprecedented novelty and exigencies. We were particularly interested to revisit Karl Weick’s insights on organizational resilience and collapse of sensemaking in the context of household organizing in the times of the COVID‐19 pandemic. While organizational scholars have focused on assessing and predicting the resilience capacity of public systems and institutions during the pandemic, they have devoted considerably less time on investigating how minimal organizational structures — for instance, families and households — have weathered the storm. Some early voices have predicted that the crisis will eventually be ‘a disaster for feminism’, because it will worsen domestic abuse, reassert traditional gender roles and further increase the domestic burden of women (Lewis, 2020). For many, juggling work and care leads to competing time demands, and previous research has indeed shown how paternalistic relationships prevent women from complying with such demands (Ruiz Castro, 2012).

While we agree with the central tenet of the essay by Helen Lewis (2020) — for instance, that the pandemic affected men and women differently, our study uncovered a more nuanced picture. While the participants confirmed a flight to gender performances, they also discovered some space for agency and resistance. Therefore, our findings echo conclusions offered by Rebecca Solnit in her book A Paradise Built in Hell (2010). Solnit (2010) presented a series of disaster case studies that not only positioned emergencies as moments of worsening conditions and great suffering but also as moments of human improvisation, solidarity and resolve. In light of these findings, future research should examine the social and individual implications of crises, not only in terms of expected struggles and difficulties but also in terms of choices and reflections individuals make along the way as they try to cope with inevitabilities. Our findings also align with Grünberg and Matei (2020) who showed that women used a range of morphologies and vocabularies in understanding how they relate to their families and workplaces as paradigms become unsustainable. Might the current crisis compel similar radical acts of self‐reflection, self‐assessment and eventual solidarity?

In our study, we observed that at the beginning of the obligatory domestic confinement the strategies of coping with extraordinary circumstances fell along the lines of accentuated gender performances, wherein awareness of gender‐centric social expectations provided some contours of intelligibility in the situation that was otherwise unfathomable. Consequently, we contend that when disaster strikes, gender performativity can offer an initial orientation amidst chaos; it compensates and reassures at the same time as it grants a temporary perspective of order. However, as the COVID‐19 crisis progressed and deepened, the need for resilient coping strategies emerged. Here we discovered a split in sensemaking options and arguably in capacity for resilience: some individuals obstinately sought to remain in gender character even if doing so made them miserable, while others chose to abandon role‐playing in favour of something ‘more meaningful’ encountered by them during the confinement.

These results are in line with earlier research on teleworking that revealed gendered processes simultaneously reinforcing traditional gender roles and enhancing work–life balance (Sullivan & Lewis, 2001). They also signal the need to revisit critical questions raised by Weick in the discussion of the Mann Gulch disaster — up to what point can we play a default (gendered) version of ourselves — the perfect wife, the strong father or the devoted mother — in conditions that require us to respond in more mindful and radical ways? Paradoxically, resilience amidst hardship can be achieved through a willingness ‘to disavow perfection’ (Weick, 1993, p. 650), a sentiment immortalized in the lines of Leonard Cohen’s (1992) song, ‘The Future’: ‘Ring all the bells that still can ring, forget your perfect offering, there is a crack (a crack) in everything, that’s how the light gets in.’

Like any other edifice of social convention, a traditional system of gender roles is not immune to ‘cracks’ over time. In times of major upheavals and unforeseen catastrophes, it may risk losing its meaning and with it, previously unquestionable utility, thus letting the light in (Alexievich, 1988). Debilitated and diminished importance of putting up a performance of gender perfection creates the possibilities for deflection. The novelty of the condition of social norms losing their significance under the predicament of force majeure ignites introspection and prompts some individuals to create their own meanings through more profound contextual reflection and attentiveness to the previously concealed aspects of their domestic lives. In the case of the COVID‐19 crisis, in the absence of rules on how to behave and with the tools of performativity cast aside, improvised self‐ruling emerged as household members stepped into unknown territory. Similar to musical improvisation, they did not know where the crisis would lead or end, but as guidelines and gender prescriptions were suspended or became irrelevant, something meaningful, unique and inimitable could materialize. Following Weick (1993), when individuals are unafraid of underperforming or disappointing others, individual resourcefulness is increased, and new options for interaction through mutual adaptation, trust and creativity are possible. When a traditional role structure ceases to make sense, the normalized and take‐for‐granted system of defining prerogatives and dividing authority becomes obsolete, and the construction of a new organization of relationships is required. Here, our conclusions again align with Weick (1993): individual coping strategies can offer sustainable sources of resilience, pave the way for mutually respectful interactions, and stabilize sensemaking when these strategies are simultaneously constitutive and destructive. Our findings demonstrate that liberation and fervent aspiration for change commences not when individuals try to reconcile their old and new selves, past and present experiences, private and professional identities, but when they give up entirely on a possibility of such reconciliation and resolutely refuse to be guided by the standards of their pre‐crisis behaviours. Exploring new imaginaries, making new vows and attaining new ideals discovered during the COVID‐19 crisis required individuals to have the courage to move beyond gender complacency. Only then could the commandments of equity in the home be envisioned and put into motion:

Almost everyone nowadays insists that participatory democracy, or social equality, can work in a small community or activist group, but cannot possibly ‘scale up’ to anything like a city, a region, or a nation‐state. But the evidence before our eyes, if we choose to look at it, suggests the opposite. Egalitarian cities, even regional confederacies, are historically quite commonplace. Egalitarian families and households are not.… Here too, we predict, is where the most difficult work of creating a free society will have to take place. (Graeber & Wengrow, 2018)

7. IMPLICATIONS, LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Although the context of the COVID‐19 crisis is unique and somewhat non‐conventional, the findings of this study have implications beyond situations of survival. First, we highlight the importance of drawing more and much closer attention to the role of gender in social sensemaking of minimal organizations such as households and families. An unfortunate result of bifurcating human life into public and private spheres is that the domestic realm has been shielded from much‐needed examination by organizational scholars. Second, the methodological approach of this study helped build and illuminate a phenomenological account of change as a product of introspective self‐questioning. By drawing insights from sensemaking framework and moral reflexivity, we demonstrate that — in the absence of a mobilized agency through critical reflection on the most trivial yet most fundamental choices of daily action — meaningful and lasting change in gender relations remains illusory. Therefore, future research should investigate the generative potential of agentic introspections and mental improvisations in fostering new forms of egalitarian intersubjectivities (Wheatley, 2013).

The limitations of our study are obvious and related to the composition of the sample. Since the participants were drawn from households with a privileged socioeconomic status and from an affluent European country, the boundary conditions of our findings must be acknowledged. The experience of confinement for middle‐class families in France is not representative of less privileged contexts. However, individual responses to the COVID‐19 crisis carry a degree of universality: although gendered reactions will differ from one context to another, gendered expectations will still play a role in constructing these reactions.

While we can and should critically dispute the extent of gender performativity across various settings and groups, it does not change the fact that individuals will look for psychological safety in the reinforcement of familiar (and justifiable) roles and doing gender is what initially offers a sense of orientation. But it is equally important to admit that one’s background, socioeconomic status and other circumstances will determine the conditions that foster capacity for radical reflexivity and deflection. We hope and encourage future research to study and extend our understanding of these issues.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interest to be reported.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors listed in alphabetical order and contributed equally to the manuscript.

Biographies

Sophie Hennekam is Professor at Audencia Business School in Nantes, France. Her research revolves around diversity issues, invisible and stigmatized populations, identity and identity transition as well as the creative workforce. She has published in journals including Human Relations, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Human Resource Management Journal and Work Employment and Society.

Yuliya Shymko is an Associate Professor at Audencia Business School in Nantes, France. Her main research interests include strategic alliances, corporate governance in emerging economies, business ethics and cross‐sector collaboration in the creative industries. She has published in journals such as Academy of Management Journal and Management Decision.

Hennekam S, Shymko Y. Coping with the COVID‐19 crisis: force majeure and gender performativity. Gender Work Organ. 2020;27:788–803. 10.1111/gwao.12479

ENDNOTE

For example, President Emmanuel Macron of France repeatedly used battlefield and military metaphors in his second address to the nation to not only describe the current situation but also affirm the firmness of actions by the government.

REFERENCES

- Alexievich, S. (1988). War’s unwomanly face. Moscow, Russia: Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. (2018). In Kohn J. (Ed.), Thinking without a banister: Essays in understanding 1953–1975. New York, NY: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. W. , & Gaskell, G. (2000). Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook for social research. London, UK: Sage. 10.4135/9781849209731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, N. , Davis, A. , & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616. 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono, J. E. , Foldes, H. J. , Vinson, G. , & Muros, J. P. (2007). Workplace emotions: The role of supervision and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1357–1367. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A. B. , Grzywacz, J. G. , Bass, B. L. , & Linney, K. D. (2005). Extending the demands–control model: A daily diary study of job characteristics, work–family conflict and work–family facilitation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 155–169. 10.1348/096317905X40097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callero, P. L. , Howard, J. A. , & Piliavin, J. A. (1987). Helping behavior as role behavior: Disclosing social structure and history in the analysis of prosocial action. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50, 247–256. 10.2307/2786825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani, G. , Ferriani, S. , & Lanza, A. (2017). Deconstructing the outsider puzzle: The legitimation journey of novelty. Organization Science, 28, 965–992. 10.1287/orsc.2017.1161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C. A. , Brown, A. D. , & Hailey, V. H. (2009). Working identities? Antagonistic discursive resources and managerial identity. Human Relations, 62, 323–352. 10.1177/0018726708101040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L. (1992). The future. New York, NY: Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: How societies choose to fail or succeed. New York, NY: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. J. , & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160. 10.2307/2095101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A. (2003). The survey handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 10.4135/9781412986328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, J. A. , Stanton, J. M. , Fisher, G. G. , Spitzmueller, C. , Russell, S. S. , & Smith, P. C. (2003). A lengthy look at the daily grind: Time series analysis of events, moods, stress, and satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1019–1033. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D. A. , Corley, K. G. , & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16, 15–31. 10.1177/1094428112452151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. New York, NY: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Graeber, D. , & Wengrow, D. (2018). How to change the course of human history. Eurozine. Retrieved from https://www.eurozine.com/change-course-human-history

- Grünberg, L. , & Matei, Ș. (2020). Why the paradigm of work–family conflict is no longer sustainable: Towards more empowering social imaginaries to understand women’s identities. Gender, Work and Organization, 27, 289–309. 10.1111/gwao.12343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, S. , Gillespi, N. , Searle, R. , & Dietz, G. (2020). Preserving organizational trust during disruption. Organization Studies. 10.1177/0170840620912705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, M. T. , & Freeman, J. (1977). Population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 929–964. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin, S. (2008). Moral selves, evil selves: The social psychology of conscience. New York, NY: Springer. 10.1057/9780230614949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, R. , Schwind, K. M. , & Heller, D. (2007). Employee well‐being: A multi‐level model linking work and non‐work domains. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16, 326–341. 10.1080/13594320701363712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, H. (2010). The logic of qualitative survey research and its position in the field of social research methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2). Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1002110

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H. (2020). The coronavirus is a disaster for feminism. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/feminism-womens-rights-coronavirus-covid19/608302/

- Locke, K. (2001). Grounded theory in management research. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, L. , & Moon, J. (2018). Disrupting the gender institution: Consciousness‐raising in the cocoa value chain. Organization Studies, 39, 1153–1177. 10.1177/0170840618787358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGahan, A. M. (2004). How industries change. Harvard Business Review, 82, 86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A. D. (1982). Adapting to environmental jolts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 515–537. 10.2307/2392528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Castro, M. (2012). Time demands and gender roles: The case of a big four firm in Mexico. Gender, Work and Organization, 19, 532–554. 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2012.00606.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shadnam, M. (2020). Choosing whom to be: Theorizing the scene of moral reflexivity. Journal of Business Research, 110, 12–23. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A. , & Shinebourne, P. (2012). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 10.1037/13620-005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solnit, R. (2010). A paradise built in hell: The extraordinary communities that arise in disaster. New York, NY: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7, 137–146. 10.7275/z6fm-2e34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, C. , & Lewis, S. (2001). Home‐based telework, gender, and the synchronization of work and family: Perspectives of teleworkers and their co‐residents. Gender, Work and Organization, 8, 123–145. 10.1111/1468-0432.00125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Symon, G. (1998). Qualitative research diaries. In Symon G. & Cassell C. (Eds.), Qualitative methods and analysis in organizational research (pp. 94–117). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tschan, F. , Rochat, S. , & Zapf, D. (2005). It’s not only clients: Studying emotion work with clients and co‐workers with an event‐sampling approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 195–220. 10.1348/096317905X39666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Eerde, W. , Holman, D. , & Totterdell, P. (2005). Editorial. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 151–154. 10.1348/096317905X40826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 628–652. 10.2307/2393339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. E. (2009). Making sense of the organization: The impermanent organization. Chichester, UK: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, D. (2013). Location, vocation, location? Spatial entrapment among women in dual career households. Gender, Work and Organization, 20, 720–736. 10.1111/gwao.12005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]