Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is a global pandemic that has caused severe health threats and fatalities in almost all communities. Studies have detected severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) in saliva with a viral load that lasts for a long period. However, researchers are yet to establish whether SARS‐CoV‐2 can directly enter the salivary glands. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the presence of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)/transmembrane serine proteases 2 (TMPRSS2) expression in salivary glands using publicly available databases. The distribution of ACE2 and TMPRSSs family in salivary gland tissue and other tissues was analyzed. The Genotype‐Tissue Expression dataset was employed to explore the ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in various body organs and salivary glands in a healthy population. The single‐cell sequencing data for salivary gland samples (including submandibular salivary gland and parotid gland) from mice were collected and analyzed. The components and proportions of salivary gland cells expressing the key protease TMPRSSs family were analyzed. Transcriptome data analysis showed that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were expressed in salivary glands. The expression levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were marginal without significant differences in different age groups or between men and women. Single‐cell RNA sequence analysis indicated that TMPRSS2 was mainly expressed in salivary gland epithelial cells. We speculate that SARS‐CoV‐2 may be entered in salivary glands.

Keywords: ACE2, COVID‐19, TMPRSS2

Highlights

Our research found that human salivary glands have a host cell receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2. This implies that the virus might gain entry into the salivary glands. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear and should further be explored.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane serine proteases 2

1. INTRODUCTION

Several unknown pneumonia cases were reported in Wuhan, Hubei, China in early December 2019. 1 , 2 Sequencing of the respiratory tract samples from pneumonia patients confirmed that they had a respiratory virus that was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). Since then, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreaks have caused significant mortality and morbidity in China. By 11 February 2020, a total of 72 314 individuals were diagnosed with COVID‐19, 1023 death cases were recorded, and more than 21 675 suspected cases were reported in China. Currently, SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cases have been recorded in almost every part of the globe. The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused major illnesses and deaths, and it has been declared a global health emergency by the World Health Organization. 3 The spread of COVID‐19 became unstoppable at the start of December 2019 and had attained the necessary epidemiological criteria to be declared a pandemic after having infected more than 100 000 people in 100 countries and regions. COVID‐19 is currently a global pandemic that has severely affected economy. 4 , 5 , 6

SARS‐CoV entry into the cell is induced by the binding of viral spike (S) protein to cellular receptors triggered by host cell proteases. The S protein of SARS‐CoV binds to angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as the host cell receptor and it is triggered by specific transmembrane serine proteases (TMPRSS) including TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS11D. 7 Current research classifies SARS‐CoV‐2 in the coronavirus family, β‐CoV, which is closely related to SARS‐CoV. 8 , 9 The SARS‐CoV‐2 genome has an identical sequence with SARS‐CoV. 10 , 11 Therefore, the researchers have proposed that SARS‐CoV‐2 and SARS‐CoV use the same receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 to gain entry into the cell. Moreover, recent studies indicate that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are potential host receptors for SARS‐CoV‐2. 11 , 12 Multiple bioinformatic studies have identified potential routes for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, salivary glands, and urinary systems. 13 , 14 , 15 A study by Xu et al 16 reported that the ACE2 receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2 was highly expressed in epithelial cells of the oral mucosa specifically in tongue. Clinical studies have also demonstrated that SARS‐CoV‐2 is present in saliva characterized by a higher viral load in the first weeks after the onset of symptom and lasted for a long duration. 17 , 18 However, it has not been established whether SARS‐CoV‐2 directly invade into the salivary glands. Therefore, this study employed a bioinformatic analysis to determine the distribution of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in salivary glands.

2. METHODS

2.1. Transcriptome data

This study explored the distribution and expression of ACE2 and TMPRSSs family in various body tissues but mainly focused on the salivary gland. The bulk RNA‐Seq profiles for normal salivary glands were collected from the Genotype‐Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (https://commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx/). The GTEx dataset incorporated 71 normal salivary gland tissues (Table S1). The expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in different organs was explored. Disparities in gender and age were examined.

2.2. scRNA‐Seq profiles from the database

The single‐cell RNA (scRNA) data for normal salivary glands in Mus musculus were obtained from the two Gene Expression Omnibus datasets, GSE113466 19 and GSE132867, 20 for the submandibular salivary gland and parotid gland, respectively. First, the scRNA data for the gland and parotid gland were analyzed separately and then merged using the “IntegrateData” function in the Seurat 3.1.4. The Seurat was used to identify different cell types following the canonical markers and cell classification in the original literature. The data were normalized using the LogNormalize method. The first 2000 highly variable feature genes were used for cell clustering analysis. Cell types with high ACE2 and TMPRSSs family expression levels were identified based on the scRNA‐Seq datasets. The cell scatter plot was generated using the t‐distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding method.

2.3. Functional enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) 21 of the normal salivary gland in the GTEx dataset was conducted to determine an overall pathway of gene‐set activity score for each sample. The gene sets having the c2/c5 curated signatures were downloaded from the Molecular Signature Database of Broad Institute. The Gene Ontology (GO)/Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) terms between the highly ACE2 expressed group and the lowly ACE2 expressed group were identified. The significant enrichment pathway was determined based on the false discovery rate of less than 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Analyzing ACE2 and TMPRSSs expression in tissues from a healthy population

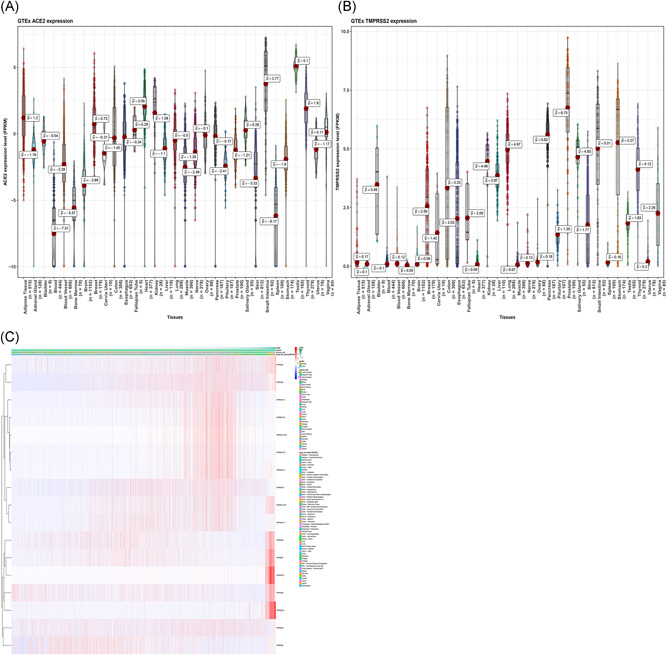

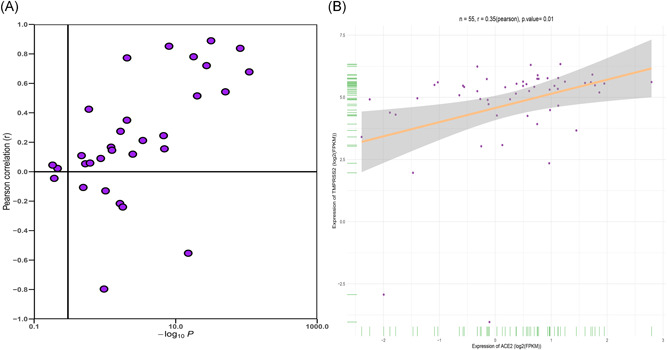

Several SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected patients exhibited potential target organs including the lung, kidney, testis, tears, and oral mucosa. We explored the vulnerable organs to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the healthy population. Data from the GTEx project indicated that ACE2 was highly expressed in the testis, small intestine, and adipose tissue, whereas the spleen and blood showed lower expression levels. In addition, the TMPRSS2 was highly expressed in the pituitary gland and prostate, whereas the spleen, heart, adipose tissue, and blood showed lower expression levels. Both ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were moderately expressed in oral mucosa and salivary glands (Figure 1A,B). The heatmap analysis showed that the TMPRSSs family and ACE2 was expressed across the organs (Figure 1C). The findings reported an increase in ACE2 and TMPRSSs family gene expression. The ACE2 expression level was positively correlated with TMPRSS2 in most organs including the salivary glands, small intestine, and kidney. On the contrary, a negative correlation between ACE2 and TMPRSS2 was observed in the fallopian tube, breast, and prostate (Table S2 and Figure 2A). In the salivary glands, we reported a positive correlation (Pearson's correlation coefficient R = .35, P = .01, N = 55; Figure 2B) whereby an increase in TMPRSS2 expression level by 1 log2 (reads per kilobase million [RPKM]) value increased ACE2 expression level by approximately 0.35 log2 (RPKM) value.

Figure 1.

RNA‐Seq analysis of the GTEx datasets. A, Violin plot of ACE2 expression in normal tissues, colored by organs; B, Violin plot of TMPRSS2 expression in normal tissues, colored by organs, the y‐axis represents the ACE2/TMPRSS2 expression levels, and the unit is FPKM, the x‐axis represents different organs; C, Heatmap of ACE2/TMPRSSs family as expressed across organs. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; FPKM, fragments per kilobase million; GTEx, Genotype‐Tissue Expression; RNA‐Seq, RNA sequencing; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in GTEx data (A) in GTEx all organs; (B) in salivary glands. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; GTEx, Genotype‐Tissue Expression; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2

3.2. Effect of age and gender differences on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression

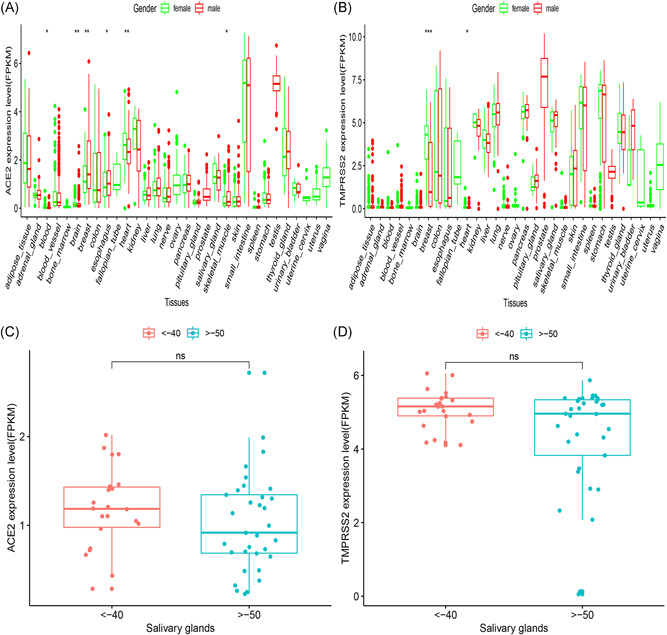

In this study, we compared and analyzed the GTEx levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in humans. The expression levels for ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were significantly altered between the male and female populations in the blood, brain, breast, heart, esophagus, and skeletal muscle organ (Figure 3A,B). A marginal but not significant difference in ACE2 or TMPRSS2 expression was observed in different age groups, or between men and women. This result was consistent with the epidemiological characteristics of over 70 000 cases released by the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on 11 February 2020 (with a 0.99: 1 ratio in Wuhan and 1.06: 1 in the whole country). 22 The level of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the salivary glands was relatively higher in the younger population compared to the elderly population (Figure 3C,D). However, no statistical significance was observed in the expression levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 based on age disparity.

Figure 3.

RNA‐Seq analysis of public GTEx datasets. A box plot showing gender disparities of (A) ACE2 and (B) TMPRSS2 across organs. The disparities of age (C, D) shown in the salivary glands. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; FPKM, fragments per kilobase million; GTEx, Genotype‐Tissue Expression; RNA‐Seq, RNA sequencing; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2

3.3. Correlation analysis

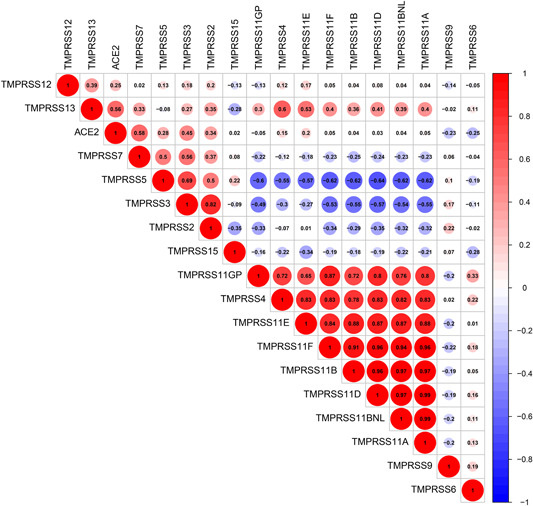

The correlation analysis of the salivary gland tissues determined the co‐expression relationship between the ACE2 and TMPRSSs family. Through Pearson's correlation analysis, ACE2 was reported to correlate with several TMPRSS genes including TMPRSS2, TMPRSS5, TMPRSS3, and TMPRSS7 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The correlation of ACE2 and TMPRSSs family in GTEx salivary gland samples. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; GTEx, Genotype‐Tissue Expression; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2

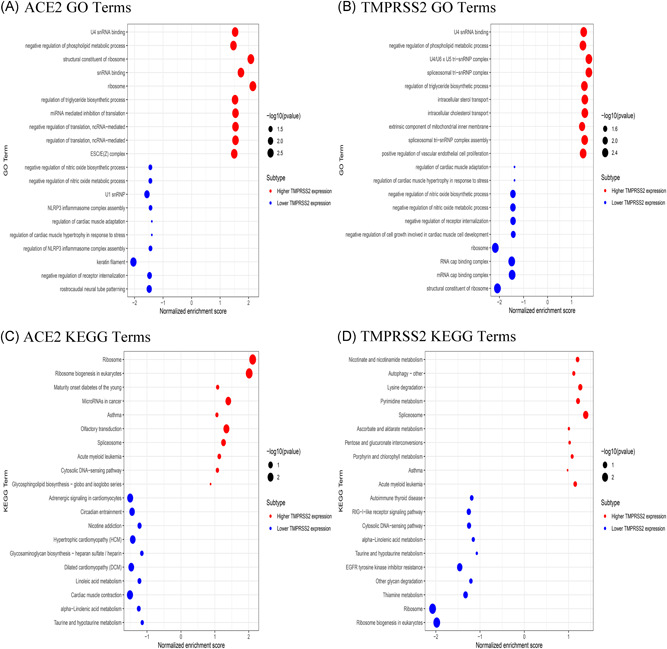

3.4. Functional enrichment analysis

The gene expression profiles of 55 healthy salivary gland samples were obtained from the GTEx dataset to examine the potential biological processes associated with ACE2 and TMPRSS2. On the basis of the median for ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression levels, samples were divided into higher expression group and lower expression group. The GSEA was conducted to determine the ACE2/TMPRSS2‐related functional enrichment categories. The enrichment of GO terms mainly occurred in the U4 snRNA binding, negative regulation of phospholipid metabolic process, and in the ribosome (Figure 5A,B). Higher expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 potentially activated the ribosomal pathway which is associated with coronavirus as reported in several studies. 23 , 24 Ribosome was identified to be involved in the synthesis of viral RNA and proteins, and virus replication. The KEGG analysis revealed that asthma, spliceosome, and autophagy were activated in the higher expression group (Figure 5C,D). Notably, previous studies have reported that the importance of the process of autophagy in virus entry and replication has been increasingly understood. 25 , 26

Figure 5.

Functional enrichment analysis using GSEA method in GTEx salivary gland samples. The top 20 GO and KEGG terms are shown. (A,C) ACE2; (B,D) TMPRSS2. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; GO, Gene Ontology; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; GTEx, Genotype‐Tissue Expression; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2

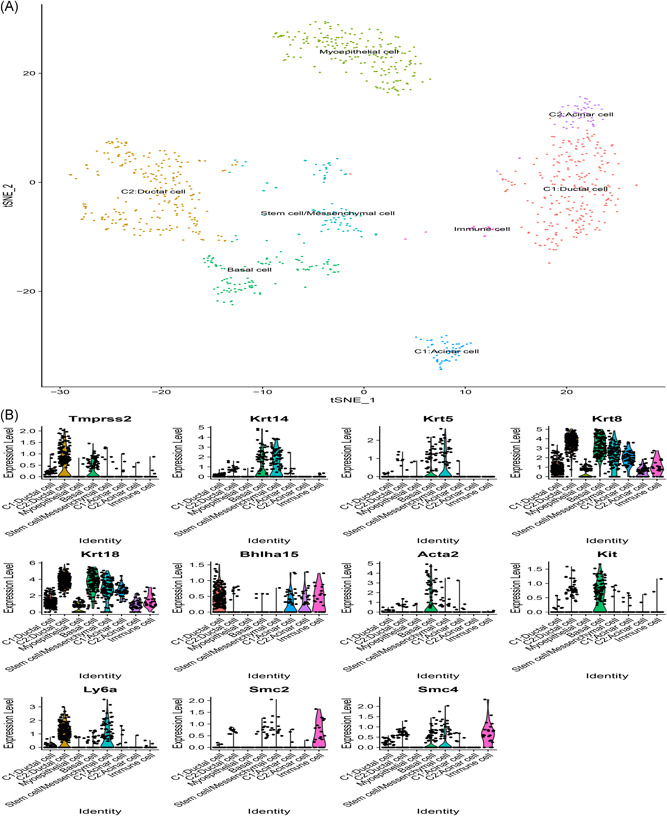

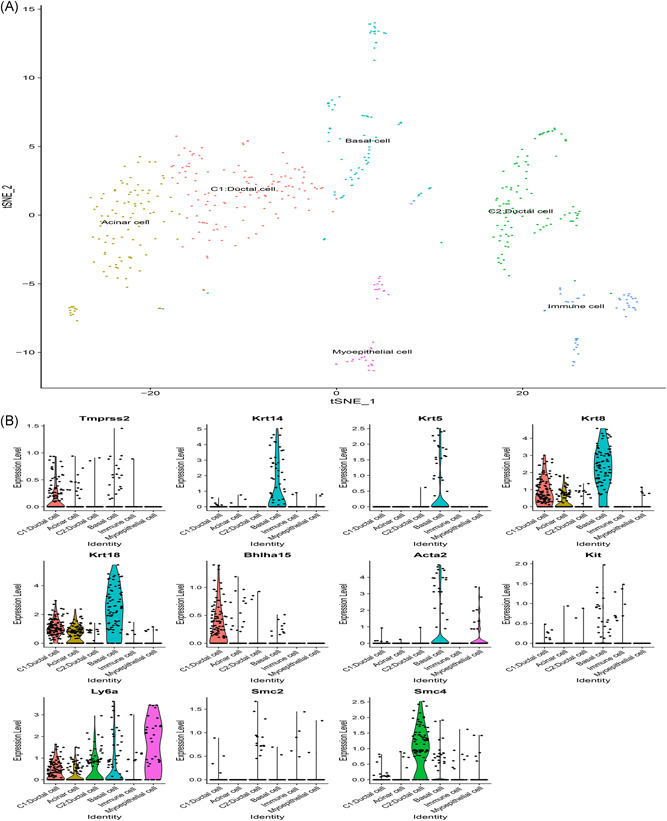

3.5. Analyzing the scRNA‐Seq data in salivary gland tissue

From the scRNA‐Seq data, expression level for ACE2 was mostly recorded at 0. ACE2 was filtered after the initial quality check thereby assessing the expression pattern for TMPRSS2 in the mouse salivary glands. We analyzed the published scRNA‐Seq dataset for submandibular and parotid glands. In the mouse submandibular gland dataset, a total of 1031 cells attained standard quality control and were retained for subsequent analyses. On the basis of the expression of a set of markers, eight distinct cell populations were identified including ductal cell, stem cell/mesenchymal cell, acinar cell, myoepithelial cell, basal cell, and immune cell (Figure 6A). It was reported that TMPRSS2 was highly localized in the ductal cell and basal cell (Figure 6B). On the contrary, TMPRSS2 expression was not observed in immune cells. In the mouse parotid gland dataset, a total of 1276 cells attained standard quality control and were retained for further analyses. Single cells were grouped into six subclusters based on the canonical markers and cell classification in the literature. We reported that TMPRSS2 was highly expressed in the ductal cell, basal cell, and acinar cell (Figure 7A,B), whereas no expression was observed in the immune cell.

Figure 6.

Single‐cell RNA‐Seq analysis of the submandibular gland in Tabula Muris from public dataset. A, Eight cell types identified by the cell markers and clustered by the tSNE method; B, Violin plot of TMPRSS2 expression across different cell types. RNA‐Seq, RNA sequencing; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2; tSNE, t‐distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

Figure 7.

Single‐cell RNA‐Seq analysis of the parotid gland in Tabula Muris from public dataset. A, Six cell types identified by the cell markers and clustered by the tSNE method; B, Violin plot of TMPRSS2 expression across different cell types. RNA‐Seq, RNA sequencing; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2; tSNE, t‐distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

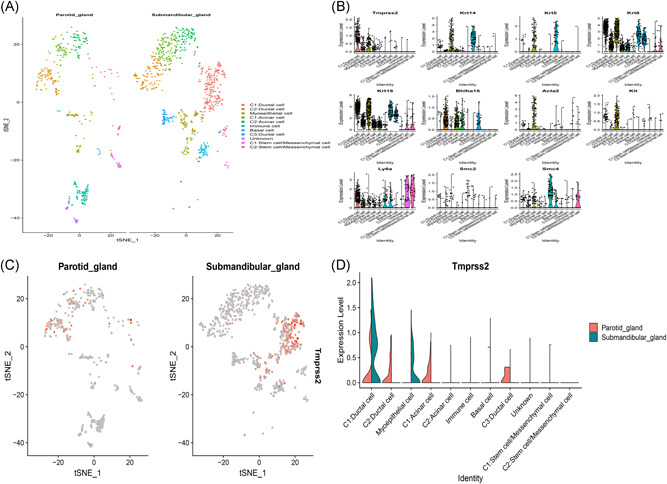

Since the parotid and submandibular glands have similar tissue, we merged the two scRNA‐Seq data into one dataset. A total of 1492 cells attained standard quality control and were retained for further analyses. On the basis of the expression of a set of markers, 11 distinct cell populations were identified including ductal cell, stem cell/mesenchymal cell, acinar cell, myoepithelial cell, basal cell, and immune cell (Figure 8A,B). The results implicated that TMPRSS2 is highly expressed in the submandibular salivary gland than in the parotid gland (Figure 8C). TMPRSS2 was highly expressed in ductal and acinar cells in parotid glands, whereas in submandibular glands, it was highly expressed in the ductal and myoepithelial cells (Figure 8D). These observations indicated that TMPRSS2 is expressed on the surface of salivary gland cells; therefore, SARS‐CoV‐2 can potentially gain entry into the salivary glands.

Figure 8.

Integration analysis of two single‐cell RNA‐Seq datasets in salivary glands. A, 11 cell types identified by the cell markers and clustered by the tSNE; B, Scatter plots of all the cells with TMPRSS2 and other genes; C, The dot plot showing the distribution of TMPRSS2 in salivary glands; D, Violin plot showing the disparities between parotid and submandibular gland of TMPRSS2 expression. RNA‐Seq, RNA sequencing; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine proteases 2; tSNE, t‐distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

4. DISCUSSION

In the last two decades, coronaviruses have caused two severe pandemics including the SARS in 2002 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome in 2012. 27 The COVID‐19 outbreak in Wuhan in December 2019 has spread to multiple regions and countries globally posing a major public health threat. With the increase in the number of cases and expansion of the scope of infection, people were paying close attention to the future development of the epidemic. 22 Currently, cases of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection have been recorded in over 100 countries in different regions; therefore, it is a public health emergency worldwide. 28 Similar to SARS‐CoV infection, the spike (S) protein of SARS‐CoV‐2 utilizes ACE2 and TMPRSS2 as the host cellular receptors to gain entry into host cells thereby rapidly replicates and spreads into body organs. Researchers have so far not developed an effective treatment or vaccine clinically approved for treating COVID‐19.

Many studies have focused on lung damage as a result of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; however, infection of the salivary glands has not been explored. Therefore, we explored the distribution of ACE2 and TMPRSSs gene expression levels in a healthy population. In addition, the differences in ACE2 and TMPRSS2 gene expression were determined based on the age and gender through the analysis of transcriptome data. Although higher expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 was observed in the female population, no statistical significance was determined. This is consistent with a previous report that indicated gender disparity was not detected. Moreover, the ACE2/TMPRSS2 expression level in the salivary glands in the younger population was marginal higher than in the elderly population, but no statistically significance was observed.

Recent studies have reported the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 in saliva with a viral load that lasts for a long duration. A report by Lu et al indicated that SARS‐CoV‐2 can be transmitted through the mucous membranes including saliva, conjunctival secretions, and tears. 29 Several reports on ophthalmologists getting infected through routine diagnosis and treatment have also been published. Moreover, a clinical study that analyzed 2019‐nCoV nucleic acid in saliva samples from COVID‐19 patients reported potential SARS‐CoV‐2 entrance into the salivary glands. 17 Therefore, it is vital to perform an in‐depth study on saliva as a SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission pathway. Findings from the scRNA‐Seq datasets indicate that TMPRSS2 is superficially expressed on the salivary gland cells. Of note, TMPRSS2 is highly expressed in the ductal cell compared to the acinar and basal cells. Therefore, we speculated that salivary glands may act as a reservoir for SARS‐CoV‐2 thereby increasing viral load in the saliva.

In addition, previous studies reported that 99% of patients did not have clinical manifestations of oral human papillomavirus (HPV). However, HPV DNA was detected in 81% in samples from oral mucosa and anti‐HPV IgA was detected in oral mucosa samples. 30 Similar to HPV infection, SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is characterized by a few symptoms from salivary gland injury. In addition, a recent pilot experiment showed that 4 out of 62 stool specimens were positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 and an additional 4 patients tested via rectal swabs had SARS‐CoV‐2 in the gastrointestinal tract and saliva. 31 Therefore, the findings from this study confirm that in addition to the respiratory tract and lung organs, SARS‐CoV‐2 can enter other organs, such as saliva and gastrointestinal tract.

In conclusion, this study used the transcriptome data to analyze the expression levels for ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in salivary glands among a healthy population. Results from the scRNA‐Seq analysis accurately located the expression and distribution of TMPRSS2 in salivary glands. TMPRSS2 is mainly expressed in salivary gland epithelial cells. These findings confirm that human salivary glands have a host cell receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2. This implies that the virus might gain entry into the salivary glands. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear and should further be explored.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jukun Song, Yamei Li, Xiaolin Huang, and Zhihong Chen wrote the main manuscript text; Jukun Song and Yongdi Li prepared all the figures; Zhu Chen and Xiaofeng Duan contributed to data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The works was supported by Guiyang Science and Technology Bureau (expression of Fox M1‐specific gene in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its stability mechanism, No.: Zhuke Contract [2018] No. 1‐84); Guiyang Science and Technology Bureau (the effect of nicotine on the growth of common bacteria in plaque biofilm, No.: SKLODR‐2016‐01), and Guiyang Science and Technology Bureau (Bacteriostasis and Clinical Evaluation of Miao Medicine Longzhangkou Liquid on Mucositis around Implant, No.: Zhuke Contract [2018] No. 1‐59).

Song J, Li Y, Huang X, et al. Systematic analysis of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in salivary glands reveals underlying transmission mechanism caused by SARS‐CoV‐2. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2556–2566. 10.1002/jmv.26045

Contributor Information

Zhu Chen, Email: 17784810646@163.com.

Xiaofeng Duan, Email: dxf11223344@163.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data could be obtained from TCGA websites.

REFERENCES

- 1. Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, et al. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):457‐460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team . The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID‐19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145‐151.32064853 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eurosurveillance Editorial Team . Note from the editors: World Health Organization declares novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) sixth public health emergency of international concern. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(5):200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gatto M, Bertuzzo E, Mari L, et al. Spread and dynamics of the COVID‐19 epidemic in Italy: effects of emergency containment measures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(19):10484‐10491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khachfe HH, Chahrour M, Sammouri J, Salhab H, Makki BE, Fares M. An epidemiological study on COVID‐19: a rapidly spreading disease. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parodi SM, Liu VX. From containment to mitigation of COVID‐19 in the US. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1441‐1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tian HY. 2019‐nCoV: new challenges from coronavirus. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;54:E001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kannan S, Shaik Syed Ali P, Sheeza A, Hemalatha K. COVID‐19 (novel coronavirus 2019)—recent trends. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(4):2006‐2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hofmann H, Geier M, Marzi A, et al. Susceptibility to SARS coronavirus S protein‐driven infection correlates with expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and infection can be blocked by soluble receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(4):1216‐1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peng YD, Meng K, Guan HQ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 112 cardiovascular disease patients infected by 2019‐nCoV. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2020;48:E004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang F, Liu N, Wu JY, Hu LL, Su GS, Zheng NS. Pulmonary rehabilitation guidelines in the principle of 4S for patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV). Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43:E004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses . The species severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019‐nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. To KKW, Tsang OTY, Leung WS, et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS‐CoV‐2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. To KKW, Tsang OTY, Yip CCY, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song EAC, Min S, Oyelakin A, et al. Genetic and scRNA‐seq analysis reveals distinct cell populations that contribute to salivary gland development and maintenance. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oyelakin A, Song EAC, Min S, et al. Transcriptomic and single‐cell analysis of the murine parotid gland. J Dent Res. 2019;98(13):1539‐1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439(7077):682‐687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention . The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID‐19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Irigoyen N, Firth AE, Jones JD, Chung BY, Siddell SG, Brierley I. High‐resolution analysis of coronavirus gene expression by RNA sequencing and ribosome profiling. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(2):e1005473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gomez GN, Abrar F, Dodhia MP, Gonzalez FG, Nag A. SARS coronavirus protein nsp1 disrupts localization of Nup93 from the nuclear pore complex. Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;97(6):758‐766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang N, Shen HM. Targeting the endocytic pathway and autophagy process as a novel therapeutic strategy in COVID‐19. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1724‐1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benvenuto D, Angeletti S, Giovanetti M, et al. Evolutionary analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2: how mutation of non‐structural protein 6 (NSP6) could affect viral autophagy. J Infect. 2020;S0163‐4453(20):30186–30189. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, Munster VJ. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(8):523‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi GJTL. COVID‐19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225‐1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. J Med Virol. 2020;92:589‐594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peixoto AP, Campos GS, Queiroz LB, Sardi SI. Asymptomatic oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in women with a histopathologic diagnosis of genital HPV. J Oral Sci. 2011;53(4):451‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

Data could be obtained from TCGA websites.