Dear Editor,

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. Risk factors associated with respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19 include older age, neutrophilia and elevated inflammatory and coagulation markers [1]. Inflammation is often accompanied by systemic hypoferremia and low iron levels may impair hypoxia sensing and immunity [2], and increase the risk of thromboembolic complications [3]—which are all of significant concern in COVID-19. However, the iron status of COVID-19 patients is unclear. Therefore, we sought to characterise iron parameters, including serum iron, in COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) patients and relate these to disease severity.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated any serum iron profiles that were measured in critically ill patients with COVID-19 within 24 h of admission to the ICU, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK, between March 31, 2020, and April 25, 2020. Relevant clinical and laboratory data were extracted from routine datasets. The number of patients who had died, had been discharged, and were still in ICU as of May 12, 2020 was recorded.

We stratified patients according to severity of hypoxemic respiratory failure on admission to ICU—severe (PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 100 mmHg) versus non-severe (PaO2/FiO2 ratio 100–300 mmHg). All patients with severe hypoxemia required invasive mechanical ventilation and prone positioning. Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare nonparametric continuous variables between these two groups. All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was defined as P < .05. Analyses were performed using PRISM version 8 (GraphPad Software).

Results

A total of 30 patients were included. Table 1 shows the demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the included patients. Overall, 17 (57%) patients were male. The median (interquartile range (IQR)) age was 57 (52–64) years.

Table 1.

Clinical, laboratory and iron profile characteristics of study cohort, total and stratified by severity of hypoxemia

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 30) | Severe (n = 10) | Non-severe (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 57 (52–64) | 57 (53–75) | 57 (52–64) | 0.949 |

| Males, n (%) | 17 (57) | 5 (50) | 12 (60) | |

| Females, n (%) | 13 (33) | 5 (50) | 8 (40) | |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR) | 13.0 (9.8–15) | 14.5 (12–20) | 13 (12–18) | 0.7512 |

| Clinical Frailty Scale, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 23 (77) | 9 (90) | 14 (70) | |

| 2 | 4 (13) | 1 (10) | 3 (15) | |

| > 3 | 3 (10) | 0 | 3 (15) | |

| Respiratory support, n (%) | ||||

| Non-invasive ventilation | 18 (60) | 7 (701) | 11 (55) | 0.509 |

| Invasive ventilation | 26 (87) | 10 (100) | 16 (80) | 0.378 |

| Prone position | 17 (57) | 10 (100) | 7 (35) | 0.004 |

| Advanced cardiovascular support, n (%) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 0.379 |

| Advanced renal support, n (%) | 10 (33) | 5 (50) | 5 (25) | 0.271 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio, median (IQR) | 127.5 (87–200.6) | 82.5 (77–87) | 190.8 (127.5–277.5) | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory data (normal range) | ||||

| Haemoglobin (g/L) (120–150), mean (SD) | 130.4 (20.1) | 124.7 (16.7) | 133.2 (21.4) | 0.280 |

| White cell count (× 109/L) (4.0–11.0), mean (SD) | 10.6 (4.8) | 11.0 (5) | 10.4 (4.7) | 0.733 |

| Lymphocyte count (× 109/L) (1.0–4.0), mean (SD) | 0.74 (0.4) | 0.50 (0.2) | 0.87 (0.42) | 0.015 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) (0–500), median (IQR) | 3286 (1302–14,227) | 9505.5 (845–5023) | 2462 (1453–9850) | 0.462 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) (1.5–4.0), median (IQR) | 6 (5.5–6.3) | 6 (5.5–6.3) | 6.1 (5.5–6.4) | 0.670 |

| CRP (mg/L) (0–5), mean (SD) | 246.2 (100.1) | 235.8 (101.8) | 251.4 (101.5) | 0.69 |

| Iron parameters (normal range) | ||||

| Ferritin (mcg/l) (10–200), median (IQR) | 1476.1 (656.6–2698) | 903.8 (566.9–2789.2) | 1566.1 (729–2511.5) | 0.569 |

| Serum iron (μmol/L) (11–30), median (IQR) | 3.6 (2.5–5) | 2.3 (2.2–2.5) | 4.3 (3.3–5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Transferrin (g/L) (1.8–3.6), median (IQR) | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) | 1.3 (0.8–1.8) | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) | 0.784 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) (16–50), median (IQR) | 9 (7–13) | 7 (6–12) | 12 (8–14) | 0.122 |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 16 (53.5) | 7 (70) | 9 (45) | 0.203 |

| Outcome as of 10 May 2020, n (%) | ||||

| Died in ICU | 6 (20) | 5 (50) | 1 (5) | |

| Still alive in ICU | 16 (53) | 3 (30) | 13 (65) | |

| Discharged alive from ICU | 8 (27) | 2 (20) | 6 (30) | |

| ICU length of stay, median (IQR), days | 8 (4–11) | 7 (4–9) | 9 (4–12) | |

Abbreviations: APACHEII Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, CRP C-reactive protein, ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation

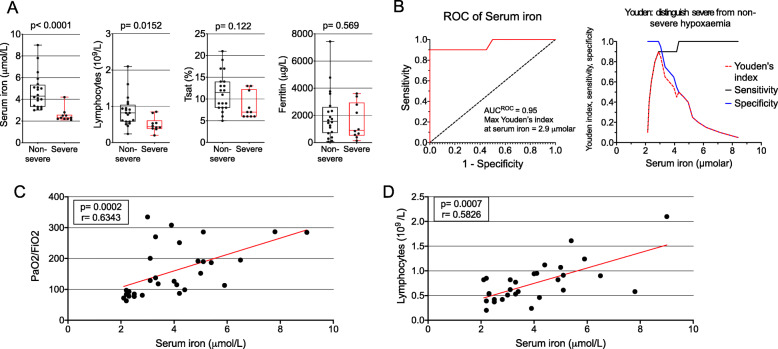

Compared with patients with non-severe hypoxemia, patients with severe hypoxemia had significantly lower levels of serum iron (median 2.3 (IQR, 2.2–2.5) vs 4.3 (IQR, 3.3–5.2) μmol/L, p < 0.001) and lymphocyte counts (mean (SD) 0.50 (0.2) vs. 0.87 (0.4), p = 0.0152). There were no statistically significant differences in transferrin saturation and serum ferritin levels between groups (Fig. 1a). The area under the curve for receiver operating characteristic curves for serum iron to identify severe hypoxemia was 0.95; the optimal Youden Index for distinguishing between severe and non-severe hypoxemia was a serum iron concentration of 2.9 μmol/L (sensitivity 0.9, specificity 1.0) (Fig. 1b). By linear regression, serum iron was associated with lymphocyte count and PaO2/FiO2 ratio (Fig. 1c, d). The proportion of patients with pulmonary emboli was numerically higher in patients with severe hypoxemia, but this was not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Associations between markers of iron status, lymphocyte count and severity of hypoxemia. a Boxplots show the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles (box); 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers); and data points (circles) of serum iron, transferrin saturation (Tsat) and serum ferritin, stratified by severity of hypoxemia. b Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and Youden Index for serum iron in distinguishing severe and non-severe hypoxemia. c Correlation serum iron and PaO2/FiO2 ratio. d Correlation between serum iron and lymphocyte count

Discussion

This is the first study describing iron status in COVID-19. Our data suggest that serum iron may be a useful biomarker for identifying disease severity in COVID-19, whilst also being a potential therapeutic target. Serum iron was lower when compared with other cohorts of non-COVID-19 ICU patients reported previously, including those with sepsis [4]. The association of serum iron with lymphocyte counts could reflect the requirement of the adaptive immune response for iron [5] and may contribute to possible T cell dysfunction reported in COVID-19 [6].

Hypoferremia is likely to be due at least in part to inflammation-driven increases in hepcidin concentrations [2]. Anti-inflammatory drugs such as tocilizumab will likely suppress hepcidin synthesis through inhibition of interleukin-6 (IL-6) [6] and so increase serum iron. Other potential therapeutic strategies include hepcidin antagonists and hypoxia-inducible factor inhibitors. Additionally, unlike hepcidin and IL-6, serum iron is measured widely and so could assist with identification and monitoring of severity of disease. Our results support performing a larger study to better characterise these patterns.

Acknowledgements

Collaborating authors:

Stuart R. McKechnie, PhD1

Simon J. Stanworth, DPhil2,3

1. Adult Intensive Care Unit, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

2. Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

3. Haematology Theme, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, UK

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease-2019

- FiO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- PaO2

Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Shah and Prof Drakesmith had full access to all of the anonymised data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: A. Shah, J.N. Frost and H. Drakesmith. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of manuscript: A. Shah and H. Drakesmith. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: A. Shah and J.N. Frost. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was required for this study. A.S. is currently supported by an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship (NIHR-DRF-10-094).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research ethics committee approval was not required for this study as per the UK Health Research Authority Decision tool (http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the local institutional board (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development) approved ethical oversight and waiver of consent. No direct patient identifiable data were collected.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Akshay Shah, Email: akshay.shah@linacre.ox.ac.uk.

Collaborators:

References

- 1.Wang D, Yin Y, Hu C, et al. Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24:188. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litton E, Lim J. Iron metabolism: an emerging therapeutic target in critical illness. Crit Care. 2019;23:81. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2373-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livesey JA, Manning RA, Meek JH, Jackson JE, Kulinskaya E, Laffan MA, et al. Low serum iron levels are associated with elevated plasma levels of coagulation factor VIII and pulmonary emboli/deep venous thromboses in replicate cohorts of patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Thorax. 2012;67:328–333. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tacke F, Nuraldeen R, Koch A, Strathmann K, Hutschenreuter G, Trautwein C, et al. Iron parameters determine the prognosis of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1049–1058. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jabara HH, Boyden SE, Chou J, Ramesh N, Massad MJ, Benson H, et al. A missense mutation in TFRC, encoding transferrin receptor 1, causes combined immunodeficiency. Nat Genet. 2016;48(1):74–78. doi: 10.1038/ng.3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riva G, Nasillo V, Tagliafico E, Trenti T, Luppi M. COVID-19: room for treating T cell exhaustion? Crit Care. 2020;24:229. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02960-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analysed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.