Abstract

While many infectious disorders are unknown to most neurologists, COVID-19 is very different. It has impacted neurologists and other health care workers, not only in our professional lives but also through the fear and panic within our own families, colleagues, patients and their families, and even in the wider public. COVID-19 affects all sorts of individuals, but the elderly with underlying chronic conditions are particularly at risk of severe disease, or even death. Parkinson’s disease (PD) shares a common profile as an age-dependent degenerative disorder, frequently associated with comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular diseases, so PD patients will almost certainly fall into the high-risk group. Therefore, the aim of this review is to explore the risk of COVID-19 in PD based on the susceptibility to severe disease, its impact on PD disease severity, potential long-term sequelae, and difficulties of PD management during this outbreak, where neurologists face various challenges on how we can maintain effective care for PD patients without exposing them, or ourselves, to the risk of infection. It is less than six months since the identification of the original COVID-19 case on New Year’s Eve 2019, so it is still too early to fully understand the natural history of COVID-19 and the evidence on COVID-19-related PD is scant. Though the possibilities presented are speculative, they are theory-based, and supported by prior evidence from other neurotrophic viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2. Neurologists should be on high alert and vigilant for potential acute and chronic complications when encountering PD patients who are suspected of having COVID-19.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pandemic, COVID-19, Parkinson’s disease, SARS-CoV-19

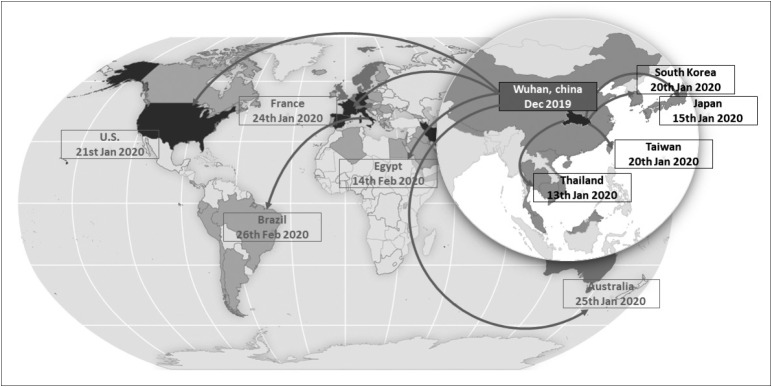

By the time this article is published, the global community will be facing an unprecedented number of more than 2.4 million patients (April 22, 2020) who are infected with a novel zoonotic virus belonging to the coronavirus family, namely, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1,2]. From an epidemic of cases with unexplained lower respiratory infections detected in Wuhan, China at the beginning of December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 infection quickly spread to 213 countries and territories in less than six months (April 22, 2020) [1]. Specifically, in Asia, there are already 48 countries with over 400,000 confirmed cases, mostly residing in China, Iran, Turkey, South Korea, India, and Japan (April 22, 2020) (Figure 1). The World Health Organization (WHO) has officially called it ‘coronavirus disease 2019’ (COVID-19), declared it a public health emergency of international concern and finally a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1].

Figure 1.

World map showing how COVID-19, first identified in Wuhan city, Hubei province, China, has spread over time to the rest of the world. On December 31, 2019, China reported a cluster of pneumonia in people associated with the Huanan seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, Hubei Province. On January 7, 2020, Chinese health authorities confirmed that this cluster was associated with a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). On January 13, 2020, Thailand reported the first imported case of 2019-nCoV infection in a 61-year-old Chinese woman from Wuhan who did not report visiting Huanan seafood market before her trip to Thailand. On January 15, 2020, Japan confirmed the first imported case of 2019-nCoV infection in a 30-year-old Chinese man who was hospitalized four days previously because of lower respiratory tract pneumonia, but did not report traveling to the Huanan seafood market. On January 20, 2020, South Korea and Taiwan confirmed the first imported cases of 2019-nCoV infection. Both cases were travelers from Wuhan, but they did not visit the Huanan seafood market. On January 20, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first case of 2019-nCoV infection in a 35-year-old man who returned to Washington State after traveling to visit his family in Wuhan. Again, he did not visit Huanan seafood market. On January 21, 2020, WHO confirmed human-to-human transmission of 2019-nCoV. On January 24, 2020, the first 2019-nCoV case was confirmed in France, representing the first confirmed case in continental Europe. On January 28, 2020, a Chinese tourist with 2019-nCoV was admitted to the hospital in Paris and died on February 14, 2020, the first mortality case outside Asia. On January 25, 2020, the first 2019-nCoV case was confirmed in Australia. On February 14, 2020, the first 2019-nCoV case was confirmed in Egypt, the first case on the African continent. On February 25, 2020, the first 2019-nCoV case was confirmed in Brazil, a 61-year-old Brazilian man who returned from Lombardy, Italy, the first case on the South American continent.

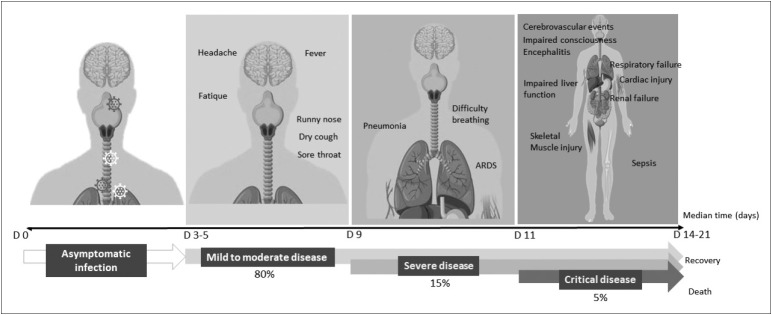

COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory disorder with symptoms ranging from no symptoms (asymptomatic) to severe pneumonia and death (Figure 2) [3]. The median age of patients is 47–51 years with the majority of cases aged between 30–69 years; 51.1–58.9% of patients are male [3,4]. After an incubation period of an average of 5–6 days (range 1–14 days), most patients with COVID-19 (80%) develop mild-to-moderate disease with typical common signs and symptoms including fever (87.9%), dry cough (67.7%), fatigue (38.1%), sputum production (33.4%), shortness of breath (18.6%), sore throat (13.9%), myalgia and arthralgia (14.8%), headache (13.6%), and chills (11.4%) [4]. Approximately 13.8% go on to develop severe disease, which is defined by dyspnea, respiratory frequency > 30/min, blood oxygen saturation < 93%, PaO2/FiO2 < 300, and/or lung infiltrates >50% of the lung field within 24–48 hours. An estimated 6.1% of cases are critical, characterized by respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ failure. A minority of patients (<5%) are either asymptomatic or die (crude fatality ratio, CFR 3.8%). Using available preliminary data from WHO, the median time from onset to clinical recovery for mild cases is approximately two weeks, and there is a three-to-six weeks recovery period for patients with severe or critical disease [4]. The time from onset to the development of severe disease is one week. So far, over 100,000 confirmed deaths have been reported by WHO, with the CFR varying by location, period, and intensity of transmission (April 13, 2020).

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram demonstrating the evolution of the four stages of COVID-19 symptoms. The first stage is asymptomatic, but the majority of the relatively rare cases who are asymptomatic on the date of identification went on to develop disease. Approximately 80% of laboratory confirmed patients had mild-to-moderate disease (Second stage) with typical signs and symptoms including fever, dry cough, fatigue, sputum production, shortness of breath, sore throat, and headache. Approximately 15% have severe disease (Third stage), manifested as severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Approximately 5–6% are critical (Fourth stage), characterized by respiratory failure, septic shock and/or multiorgan failure.

What does this mean for neurologists? Neurologists may be involved in the care or management of COVID-19 patients in different situations. 1) COVID-19 is a pandemic, which means that neurologists in any part of the world are not excluded from the risk of exposure to the disease, either by encountering COVID-19 patients or infection from other modes of transmission. COVID-19 is transmitted via droplets and fomites during close unprotected contact between an infector and an infectee. Even though most infections were reported to occur within households rather than in health care settings, figures from China’s National Health Commission show that more than 3,300 health care workers had been infected as of early March 2020 and that 22 had died [4,5]. In Italy, 20% of responding health-care workers were infected, and some have died. As shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) remain an important issue, health care workers, including neurologists, should be aware of various protective measures when confronting patients with suspected infection so they can protect themselves and avoid passing the infection to their families [6]. 2) Neurologists may encounter individuals who are unaware they are infected, such as those who present with headache, which is observed in 13.6% of patients. Presymptomatic patients may also seek neurological or rhinological advice for the symptoms of hyposmia and hypogeusia, recognized in over 80% of COVID-19 patients, which can occur before the onset of other symptoms [7].

3) Neurologists may be involved in the care of patients with the highest risk for severe disease, including people aged over 60 years and those with underlying conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease and cancer, when neurological presentations consist of alterations of consciousness and respiratory failure due to brainstem involvement [4,8]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also included people who live in a nursing home or long-term care facility as another risk factor for severe illness [9]. Although neurological disorders are not included in the highest risk category in the WHO report, the evidence is mounting that patients with chronic neurological disorders may be at risk for severe COVID-19. In addition to respiratory, fecal, and blood specimens, SAR-CoV-2 has recently been detected in the CSF of two patients with meningitis/encephalitis [10,11]. According to a mortality report from South Korea, patients with underlying neurological disorders of mainly dementia and stroke with an age of over 70 years represented 18.5% of all cases (10 out of 54 cases) [12].

4) For those who survive, a spectrum of neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 have been reported in 36.4% of cases, ranging from dizziness, headache, hyposmia, hypogeusia, dysphagia, muscle pain, seizures, loss of consciousness, and nerve pain with the list continuing to grow [10,11,13-15]. Another series involving 58 patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection reported a much higher prevalence of neurological impairment in 49 patients (84%), consisting of encephalopathy, prominent agitation, confusion and corticospinal tract signs [16]. Neurological presentations were commonly observed in those with severe infection, with stroke being the most common etiology, but cases with encephalitis are also increasingly recognized [15,17]. Two cases of documented CSF invasion presenting with encephalitis and one possible case of acute necrotizing encephalopathy from cytokine storm syndrome following COVID-19 have been reported [10,11,14]. Evidence is also emerging that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the CNS through hematogenous or an upper nasal trancribial route that enables SARS-CoV-2 to reach the brain, or potentially peripheral terminals [18]. Another intriguing hypothesis is related to the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors to treat hypertension and diabetes [19]. As ACE2 is the receptor for SARS-CoV-2, the use of ACE inhibitors could potentially lead to increased expression of ACE2, making the brain cells (e.g., endothelial cells in the brain, neurons, etc.) even more vulnerable to this viral infection. Clinical studies are currently underway to test this hypothesis.

5) Finally, since the best preventative measure is to avoid being exposed to the virus, neurologists should strictly follow preventive and control measures, which may have significant impact on how they manage their patients either as in- or out-patients. Moreover, neurologists should be ready to prepare and adopt certain initiatives to ensure that they are safe, but, at the same time, patients’ neurological care is not neglected or ignored during this challenging period [20,21].

As PD patients share common characteristics with reported COVID-19 patients in terms of age, comorbidities, and a risk of respiratory dysfunction, it is plausible that PD patients or at least certain PD populations (e.g., advanced stage) may be at potential risk for severe COVID-19. The aim of this review is to explore the risk of COVID-19 in PD based on the susceptibility to severe disease, its impact on PD disease severity, potential long-term sequelae, and challenges of PD management during this outbreak, where neurologists need to balance how we can maintain effective care for PD patients without exposing them, or ourselves, to the risk of COVID-19.

ARE PARKINSON’S DISEASE PATIENTS SUSCEPTIBLE TO SEVERE COVID-19?

Clinical vignette

A 77-year-old Korean man with Parkinson’s disease dementia was admitted to the emergency room with alteration of consciousness on February 23, 2020. His past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease (CAD). At admission, he was minimally responsive and hypotensive (61/35, PR = 79/min) with a body temperature of 36°C. He had tachypnea (RR = 26/min) with oxygen saturation of 90% on room air. A diagnosis of septicemia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was suspected and he was treated with inotropes, antibiotics, and respiratory support.

Chest computed tomography revealed diffuse bilateral ground glass opacities and RT-PCR assays of the throat and nasal swab samples were reported two days later as positive for SARS-CoV-2, confirming the diagnosis of COVID-19. The family decided against resuscitation and he was given supportive treatment, without a ventilator, in a negative pressure isolation room. He died six days after admission from respiratory failure (Personal communication with Prof. Ho-Won Lee, Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital, South Korea).

Presence of comorbidities, especially cardiovascular disease

This case illustrates an example of a critical COVID-19 patient who fulfilled the risk criteria for severe disease, including old age and cardiovascular disease. This case also provides perspectives that we can all learn from in terms of the understanding and treatment of this disease, as well as preventive precautions for family members and wider society. From the underlying disease perspective, a cardiovascular disorder comorbidity is considered a high risk for severe disease, with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease reported as between 2.5–12.1% of patients with COVID-19 [3,22]. Compared to the overall CFR of 3.8%, the presence of comorbid conditions significantly increases the CFR, with the highest for cardiovascular disease (13.2%), followed by diabetes (9.2%), hypertension (8.4%), chronic respiratory disorder (8.0%), and cancer (7.6%) [4]. CFR can also increase with age, with the highest mortality observed among people over 80 years (CFR 21.9%) as well as male sex (CFR 4.7%) and retirees (CFR 8.9%) [4]. Although PD is not included as a risk factor for severe disease, PD was mentioned as an underlying disorder associated with mortality in some case series, such as in our case vignette [23].

Whether PD itself poses a risk for severe disease is not entirely clear. Based on published literature since the identification of COVID-19, there is no conclusive evidence of such a risk in PD. The experience from the three most heavily affected regions in Italy does not show an apparent increased risk, although there are no systematic data available [24]. While the risk cannot be confirmed for the whole PD population, there are several theoretical possibilities that a risk for severe disease may still occur in certain PD subgroups. Indirect risk can be estimated through the strong link between PD and a number of comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease. Several cardiac abnormalities have been observed in PD patients, including cardiac autonomic dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, CAD, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death [25]. While the associations between cardiovascular risk factors and PD are not straightforward, the link between cardiovascular disease and PD may be related to a shared sedentary lifestyle in both conditions [26]. In addition, diabetes and cerebrovascular disease are also identified as frequent comorbidities in PD patients and are recognized risk factors for severe disease with COVID-19 [27,28].

Subgroups of Parkinson’s disease patients with underlying respiratory dysfunction and increased risk for aspiration pneumonia

Direct risk for a severe disease with COVID-19 is likely to occur in a subgroup of PD patients, particularly those with respiratory dysfunction. Indeed, dyspnea is a common symptom in PD, observed in 39.2% of patients without a history of lung or heart disease [29]. With frequent cardio-pulmonary comorbidities among PD patients, the number of PD patients with dyspnea is likely to be higher in clinical practice than that observed in clinical trials. When comorbidities are excluded, dyspnea in PD is primarily associated with advanced disease with contributing factors from respiratory muscle weakness, axial manifestations, and abnormal posture (e.g., camptocormia, stoop), causing respiratory muscle rigidity and poor respiratory excursions, finally resulting in ventilatory failure [29,30]. In PD, dyspnea may also occur as part of nonmotor fluctuations, frequently associated with anxiety and depression [31]. Furthermore, the presence of restrictive or obstructive respiratory dysfunction can potentially predispose PD patients to sleep apnea, further compromising these patients’ night-time breathing function [32]. While inspiratory muscle weakness may be clinically evident in advanced stage patients, it has recently been found to be present at a subclinical level in early stage patients whose pulmonary function tests did not disclose any restrictive or obstructive disorders [33]. Central effects of respiratory dysfunction in PD cannot be discounted as an early stage of neurodegeneration in PD also involving brainstem nuclei, affecting the respiratory center in the medulla, which is also targeted by SARS-CoV-2 infection [8]. Therefore, PD patients with underlying respiratory dysfunction could be at significant risk of respiratory failure if infected by SARS-CoV-2.

Pneumonia was identified as the foremost reason for hospital admissions and the most common cause of death among PD patients [34,35]. The inverse association also demonstrates that PD by itself confers a higher probability of dying from pneumonia [36]. As PD progresses, mastication is affected and swallowing is impaired by bradykinesia, rigidity, and dyskinesia, causing pooling of saliva in the mouth, leading to drooling or aspiration of secretions [37,38]. This is important as aspiration of saliva may also occur in between meals. In advanced patients who are weak and frail, their cough becomes weaker because of chest wall rigidity and decreases in the sensory component of the cough reflex. This combination represents a perfect scenario for aspiration pneumonia. As COVID-19 is mainly transmitted through respiratory droplets from coughing and sneezing ultimately infecting alveolar epithelial cells, PD patients may predispose themselves to severe pneumonia by aspirating infected secretions into the lower respiratory tract. However, while this mechanism may seem plausible, there is no published literature supporting this association in PD patients with COVID-19.

Possible altered immune responses in Parkinson’s disease patients

Relative to viruses that cause human upper respiratory tract infection, viruses that cause lower respiratory tract infection are smaller and their infections are mostly limited to tracheobronchitis in healthy individuals but can cause viral pneumonias in immunocompromised patients. Before the outbreak of COVID-19, the most frequent virus that caused acute lower respiratory infections in China was respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), but influenza viruses were the main cause in adults and the elderly [39]. Human coronavirus represented only a minority (1.4%) within this Chinese cohort. If we assume that PD represents a risk for severe disease consisting of pneumonia and ARDS with COVID-19, it is important to determine the immune status responses in general PD populations or certain PD subgroups to identify if they are immunocompromised. Indeed, the concern whether PD can lower immunity in affected patients, making them more susceptible to COVID-19, was recently shared by PD patients and caregivers [40]. Importantly, evidence of dysregulation of immune responses in patients with severe COVID-19 infection is emerging, characterized by elevated levels of infection-related biomarkers and inflammatory cytokines, including a low number of T cells in more debilitating and severe cases [41]. Both helper T cells and suppressor T cells in patients with COVID-19 were found to be below normal levels, with the lowest level of helper T cells in the severe group. In severe cases, the percentage of memory helper and regulatory T cells was also decreased. As PD typically affects people from the sixth decade of life, it is also important to determine a state of immunosenescence, which is associated with dramatic changes in the distribution and competence of immune cells, leading to the loss of adaptive immunity and the gain of nonspecific innate immunity, leaving older individuals susceptible to infection and cancer and unprotected from chronic tissue inflammation [42]. The cooccurrence of weakened adaptive immunity with a bias toward nonspecific tissue inflammation (‘inflammaging’) probably explains why the elderly, particularly those above 80 years, are highly susceptible to severe COVID-19.

DO PARKINSON’S DISEASE PATIENTS DETERIORATE DUE TO THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC?

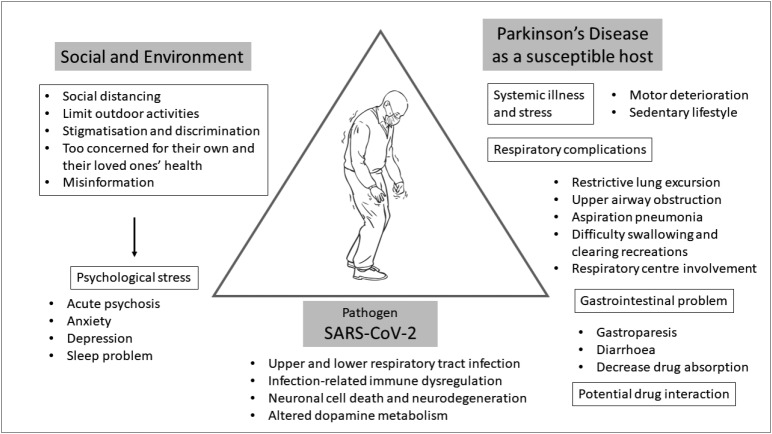

To adequately address this question, we need to determine various aspects of how COVID-19 by itself and by environmental and social factors could have an effect on PD patients (Figure 3). At this moment, there are no available data that provide sufficient information on how COVID-19 itself has an effect on parkinsonian symptoms except for scattered mortality case reports, which include PD among many other underlying disorders. While this lack of information may be interpreted as there being no significant effect of COVID-19 on the overall symptoms of PD patients, it is probably too early to estimate this association and neurologists should be on high alert to evaluate parkinsonian symptoms comprehensively with a particular emphasis on respiratory function for those infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram depicting the disease triangle of COVID-19 in Parkinson’s disease (PD), showing possible interactions between PD patients, the environment, and the pathogen (SARS-CoV-2). Diagram reflecting how COVID-19 may affect Parkinson’s disease patients, ranging from respiratory complications, gastrointestinal symptoms, worsening motor symptoms due to systemic infection, and multiorgan failure when the disease becomes critical. PD patients may also have drug interactions between monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) and cough syrup or nasal decongestants. The impact of COVID-19 on the social and environment of PD patients may contribute to psychological stress and worsening outcomes. The pathogen, SARS-CoV-2, has been shown to cause primarily lower respiratory tract infections, but potentially can lead to immune dysregulation, neuronal cell death and altered dopamine metabolism. The disease triangle is a conceptual model that shows the interaction between the environment, the host, and the infectious agent 71. This model can be used to predict the epidemiological outcomes in public health.

Possible direct impact of COVID-19 on Parkinson’s disease patients with COVID-19

Despite a lack of specific data on COVID-19, the available evidence indicates that PD patients can deteriorate following systemic infections [43]. The clinical spectrum of this phenomenon is wide, ranging from mild worsening to akinetic crisis [43]. Fever and delirium are two of the most important factors found to be associated with motor deterioration and respiratory tract infection found to be the most common contributor [44,45]. As fever is the most common symptom of COVID-19, observed in 87.9% of affected patients and up to 12.3% experience a high fever of more than 39.0°C, there is a strong possibility of subacute worsening of parkinsonism for PD patients with COVID-19 [3,4]. The prevalence of this phenomenon was found to be between 25–32.5% with advanced disease, characterized by long disease duration, high Hoehn & Yahr (HY) stage, cognitive dysfunction, and high dopaminergic medication dosages as potential risk factors [44,45]. The combination of fever and altered dopaminergic medication intake can potentially predispose PD patients to Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome, which is a movement disorder emergency, requiring immediate and aggressive management [46]. Despite improvement of the underlying infection, not all PD patients with this phenomenon fully recover, and some are left with significant disability. Fatal cases have also been reported [45]. The mechanisms underlying this motor deterioration are likely to be complex with variable contributions from individual cases, but include altered medication intake during systemic illnesses, changes in the pharmacodynamics of dopaminergic medications, altered dopamine metabolism in the brain, peripheral inflammatory processes or circulating toxins or cytokines [43]. Therefore, PD patients who possess these risks should be carefully observed and monitored for motor deterioration during a period of active SARS-CoV-2 infection, which should also be extended into the convalescence period.

Possible indirect impact of COVID-19 on Parkinson’s disease patients without COVID-19

The impact of universal preventative measures for COVID-19 exposure on symptoms, functions, activities and stress of PD patients should not be ignored [47]. Advice for everybody to ‘stay-athome’ can limit patient’s outdoor physical activities and mobility, resulting in a sedentary lifestyle for some patients, potentially leading to worsening outcomes. Social distancing limits face-to-face family visits to patients who live alone, and may result in feelings of loneliness and depression. When patients stay at home, they are more likely to spend more time watching the television, listening to the radio and using social media with their 24-hour broadcasting of COVID-19 situations, potentially increasing psychological stress, worsening anxiety and depression that are already common nonmotor symptoms in PD patients. With high levels of fear, PD patients and their families may not think clearly and rationally when reacting to COVID-19, potentially leading to other psychosocial challenges, including stigmatization and discrimination [48]. Psychological stress can affect various motor symptoms, such as tremor, gait, and dyskinesia, as well as reduce the efficacy of dopaminergic medications [49,50].

ARE THERE POTENTIAL CONCERNS FOR POSTENCEPHALITIC PARKINSONISM WITH COVID-19?

So far, no reports of acute parkinsonism following COVID-19 have been reported in the literature. It remains to be seen if SARS-CoV-2 can induce parkinsonism following an episode of encephalitis. The issue of a viral etiology of encephalitis lethargica and postencephalitic parkinsonism continues to be a matter of debate. Much of the linkage of parkinsonism with influenza and many other viruses stem from an outbreak of encephalitis lethargica (EL), also known as von Economo’s disease, and postencephalitic parkinsonism that occurred subsequent to the 1918 pandemic influenza outbreak caused by a type A H1N1 influenza virus [51]. The cause of EL and the link to subsequent postencephalitic parkinsonism remains controversial with clinical features showing both similarities and distinct symptomatology to PD. Following an acute episode, the chronic phase of postencephalitic parkinsonism developed one to five years later, but it could also follow immediately, or more than a decade later, with typical clinical presentations involving upper limb bradykinesia and stiffness associated with frequent episodes of kinesia paradoxica, oculogyric crisis, and psychiatric disturbances [52]. Perhaps, EL is not necessarily a prerequisite to developing postencephalitic parkinsonism, but merely a contributing factor [52]. Although direct evidence for influenza virus has never been substantiated in these cases, proving a negative is also difficult. Despite the etiological controversy, people born during the time of the pandemic influenza outbreak of 1918 have a two-to-three fold-increased risk of PD than those born prior to 1888 or after 1924 [53-55]. While EL and COVID-19 involve different primary organs for their clinical manifestations, they are both pandemics affecting more than one million people with a link to neurotrophic viruses. In addition to parkinsonism, there is a theoretical possibility that SARS-CoV-2 may contribute to accelerated CNS aging in survivors, which could manifest months or years after the infection [56]. Therefore, the medical community should be cautious of neurological comorbidities of COVID-19 that may occur following an outbreak.

MANAGEMENT OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE DURING THE COVID-19 OUTBREAK

As the outbreak of COVID-19 continues globally, neurologists face challenges with new tasks related to the care of COVID-19 patients and existing tasks in providing a continuum of care for their neurological patients, but in a very different situation from their usual clinical practice. Most of the adjustments were not planned in advance and involve maximizing and reallocating human, clinical, and research resources to the priority list of taking care of COVID-19 patients. Undoubtedly, these changes not only affect the routine care of PD patients but also highlight a number of important issues that neurologists should be aware of or consider implementing during this outbreak.

Concerns on dopaminergic medications and device-aided therapies

As mentioned above, PD patients may experience a subacute worsening of their condition, especially motor symptoms, during systemic infections, potentially as a result of altered medication intake and changes in the pharmacodynamics of dopaminergic medications. For those with mild symptoms of COVID-19, patients should be advised to observe their symptoms closely and to seek consultation if their condition, particularly respiratory symptoms, significantly worsen. While most dopaminergic medications can be continued during a period of systemic infections without any absolute contraindications, caution should be noted with the use of cough syrup containing dextromethorphan and cyclobenzaprine or nasal decongestants containing pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, and phenylpropanolamine with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (e.g., selegiline and rasagiline) for potential drug interactions that can intensify sympathomimetic activities [57].

Antiviral (e.g., favipiravir, atazanavir, iopinavir/ritonavir) and anti-malarial (chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine) drugs are being tested for COVID-19 without any specific interactions with dopaminergic medications reported. Therapeutic implications of amantadine, an agent that can block a pore in the envelope protein of SARS-CoV and is no longer used as an antiinfluenza agent due to its high resistance, remain unexplored as a potential treatment of COVID-19 [58].

Patients with device-aided therapies, including deep brain stimulation (DBS), apomorphine and levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel infusions may encounter problems related to hardware, acute adverse events, or severe symptom fluctuations during this outbreak [59-61]. While the recommendations are to postpone device-aided therapies for all new cases, acute problems may arise among those who are already on one of these treatments where immediate interventions may be necessary. For example, if the battery for a DBS system stops working completely and the DBS is no longer effective, patients may experience a significant return of PD symptoms. Although most DBS procedures are considered elective, it is not an elective procedure if it is the end of battery life. In these situations, decisions should be made individually by taking into consideration the risk of complications, exposure risk to COVID-19 for both patients and health care workers, and the availability of all resources to treat that particular complication during this outbreak. In places where there are no limitations of resources, elective procedures can be resumed but full consultations with various experts and appropriate health authorities should be undertaken to ensure that it is safe to do so.

Concerns on outpatient and ambulatory care settings of PD: emerging roles of telemedicine

Another challenge for us as neurologists is how to maintain effective care for PD patients without exposing them to the risk of COVID-19 in the hospital. CDC recommends healthcare facilities delay elective ambulatory provider visits and adjust the way they triage, assess, and care for patients by using methods that do not rely on face-to-face care, such as the use of telemedicine [62]. Telemedicine encompasses a broad range of health care tools, including real-time interactive or synchronous audio and video communications between a patient and a provider (e.g., video conferencing, smartphone health care applications), and other telehealth services, such as simple telephone communication, email and text messages, and remote monitoring of patient data from wearables [20]. Previous studies have suggested that telemedicine for PD is feasible when delivered either in the home or in an off-site clinic or nursing home setting [63]. Most studies have also reported that an adequate and reliable motor examination can be performed via telemedicine with the motor section of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS-III) [64-66]. However, limitations remain for the examination of rigidity, postural instability, and cognitive dysfunction [67]. Benefits with telemedicine are also extended to cost savings, reduction in travel distance, and a reduction in time spent attending appointments [63]. Moreover, rehabilitation and allied health services can be delivered remotely with success stories demonstrated on the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment and physical therapy assessments [68,69]. In general, patient’s views on telemedicine have been favorable for the main advantages, including access to specialists and convenience, but tempered by the concern of loss of hands on care [70]. However, issues with laws, regulations, policies and patient’s confidentiality with telemedicine need to be addressed by the parties involved.

CONCLUSION

While many infectious disorders are unknown to most neurologists, COVID-19 is very different. It has made itself known to neurologists and other health care workers not only in their professions but also because of the fear and panic caused within our own families, colleagues, patients and their families, and the wider public. Since the identification of SARS-CoV-2 on New Year’s Eve 2019, it has spread to 213 countries on almost all continents in less than six months and was declared by WHO as a global pandemic. During this time period, COVID-19 has shown that it is not just a respiratory disorder as neurological complications start to emerge, ranging from mild headache and dizziness to acute encephalitis and loss of consciousness. COVID-19 affects all individuals, but it causes high mortality among the elderly and those with various underlying chronic medical conditions. PD patients are probably included in this at-risk group and the whole PD community should act together to understand, prevent, and protect themselves from COVID-19. If prevention is not possible and PD patients get infected, they should be closely monitored for worsening of their parkinsonian symptoms and signs of severe disease, especially with respect to respiratory function. It is likely that advanced PD patients with existing underlying respiratory dysfunction are particularly at-risk for severe disease and eventually respiratory and multiorgan failure. Those elderly PD patients with comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes) will have a mortality risk that is even higher. While no specific treatments are yet available, prompt supportive management of respiratory function is likely to influence outcomes. Based on its nature of neurotropism, sequelae may start to reveal themselves with time. Some early evidence of hyposmia and encephalitis are important clues that neurologists should continue to follow COVID-19 patients even though they are seronegative and discharged home since long-term complications, including parkinsonism, are all possible.

Acknowledgments

Roongroj Bhidayasiri is supported by a Thailand Science Research and Innovation grant (RTA6280016), International Research Network grant (IRN59W0005) of the Thailand Research Fund, Chulalongkorn Academic Advancement Fund into Its 2nd Century Project of Chulalongkorn University (2300042200), and Center of Excellence grant to Chulalongkorn University (GCE 6100930004-1).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. World Health Organization; 2020 [updated 2020; cited 2020 9 April]; Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavisus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The L. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferioli M, Cisternino C, Leo V, Pisani L, Palange P, Nava S. Protecting healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 infection: practical indications. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0068-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Groups at Higher Risk for Severe Illness. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2020 [updated 2020; cited]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html.

- 10.Zhou L, Zhang M, Wang J, Gao J. Sars-Cov-2: Underestimated damage to nervous system. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020:101642. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, et al. A first Case of Meningitis/Encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korean Society of Infectious D, Korea Centers for Disease C, Prevention Analysis on 54 Mortality Cases of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 10, 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e132. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID19-associated Acute Hemorrhagic Necrotizing Encephalopathy: CT and MRI Features. Radiology. 2020:201187. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, et al. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nath A. Neurologic complications of coronavirus infections. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein BC, Busis NA. COVID-19 is catalyzing the adoption of teleneurology. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldman G, Mayeux R, Claassen J, Agarwal S, Willey J, Anderson E, et al. Preparing a neurology department for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): Early experiences at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emami A, Javanmardi F, Pirbonyeh N, Akbari A. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8:e35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:29. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papa SM, Brundin P, Fung VSC, Kang UJ, Burn DJ, Colosimo C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mds.28067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scorza FA, Fiorini AC, Scorza CA, Finsterer J. Cardiac abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsonism. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;53:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potashkin J, Huang X, Becker C, Chen H, Foltynie T, Marras C. Understanding the links between cardiovascular disease and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2020;35:55–74. doi: 10.1002/mds.27836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yue X, Li H, Yan H, Zhang P, Chang L, Li T. Risk of Parkinson Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Cohort Studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3549. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong CT, Hu HH, Chan L, Bai CH. Prevalent cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease in people with Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1147–1154. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S163493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baille G, Chenivesse C, Perez T, Machuron F, Dujardin K, Devos D, et al. Dyspnea: An underestimated symptom in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;60:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baille G, Perez T, Devos D, Machuron F, Dujardin K, Chenivesse C, et al. Dyspnea Is a Specific Symptom in Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9:785–791. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witjas T, Kaphan E, Azulay JP, Blin O, Ceccaldi M, Pouget J, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: frequent and disabling. Neurology. 2002;59:408–413. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shill H, Stacy M. Respiratory function in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neurosci. 1998;5:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baille G, Perez T, Devos D, Deken V, Defebvre L, Moreau C. Early occurrence of inspiratory muscle weakness in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okunoye O, Kojima G, Marston L, Walters K, Schrag A. Factors associated with hospitalisation among people with Parkinson’s disease - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;71:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pennington S, Snell K, Lee M, Walker R. The cause of death in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:434–437. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bugalho P, Ladeira F, Barbosa R, Marto JP, Borbinha C, Salavisa M, et al. Motor and non-motor function predictors of mortality in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2019;126:1409–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00702-019-02055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leopold NA, Kagel MC. Laryngeal deglutition movement in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48:373–376. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis JA, Molfenter S, Troche MS. Predictors of Residue and Airway Invasion in Parkinson’s Disease. Dysphagia. 2020;35:220–230. doi: 10.1007/s00455-019-10014-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng L, Li Z, Zhao S, Nair H, Lai S, Xu W, et al. Viral etiologies of hospitalized acute lower respiratory infection patients in China, 2009-2013. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad S, Holla VV, Neeraja K, Surisetti BK, Kamble N, Yadav R, et al. Parkinson’s disease and COVID-19: Perceptions and implications in patients and caregivers. Mov Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mds.28088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Aging of the Immune System. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13 Suppl 5:S422–S428. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201602-095AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brugger F, Erro R, Balint B, Kagi G, Barone P, Bhatia KP. Why is there motor deterioration in Parkinson’s disease during systemic infections-a hypothetical view. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2015;1:15014. doi: 10.1038/npjparkd.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umemura A, Oeda T, Tomita S, Hayashi R, Kohsaka M, Park K, et al. Delirium and high fever are associated with subacute motor deterioration in Parkinson disease: a nested case-control study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng KS, Dorfman BJ, Christos PJ, Khadem NR, Henchcliffe C, Piboolnurak P, et al. Clinical characteristics of exacerbations in Parkinson disease. Neurologist. 2012;18:120–124. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318251e6f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajan S, Kaas B, Moukheiber E. Movement Disorders Emergencies. Semin Neurol. 2019;39:125–136. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1677050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helmich RC, Bloem BR. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Parkinson’s Disease: Hidden Sorrows and Emerging Opportunities. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10:351–354. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hemmerle AM, Herman JP, Seroogy KB. Stress, depression and Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2012;233:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zach H, Dirkx MF, Pasman JW, Bloem BR, Helmich RC. Cognitive Stress Reduces the Effect of Levodopa on Parkinson’s Resting Tremor. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23:209–215. doi: 10.1111/cns.12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taubenberger JK. The origin and virulence of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus. Proc Am Philos Soc. 2006;150:86–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoffman LA, Vilensky JA. Encephalitis lethargica: 100 years after the epidemic. Brain. 2017;140:2246–2251. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maurizi CP. Why was the 1918 influenza pandemic so lethal? The possible role of a neurovirulent neuraminidase. Med Hypotheses. 1985;16:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(85)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poskanzer DC, Schwab RS. Cohort Analysis of Parkinson’s Syndrome: Evidence for a Single Etiology Related to Subclinical Infection About 1920. J Chronic Dis. 1963;16:961–973. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(63)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravenholt RT, Foege WH. 1918 influenza, encephalitis lethargica, parkinsonism. Lancet. 1982;2:860–864. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90820-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lippi A, Domingues R, Setz C, Outeiro TF, Krisko A. SARS-CoV-2: at the crossroad between aging and neurodegeneration. Mov Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mds.28084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pray S. Interactions Between Nonprescription Products and Psychotropic Medications. U.S. Pharmacist; 2007 [updated 2007; cited]; Available from: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/interactions-between-nonprescription-products-and-psychotropic-medications.

- 58.Torres J, Maheswari U, Parthasarathy K, Ng L, Liu DX, Gong X. Conductance and amantadine binding of a pore formed by a lysine-flanked transmembrane domain of SARS coronavirus envelope protein. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2065–2071. doi: 10.1110/ps.062730007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jitkritsadakul O, Bhidayasiri R, Kalia SK, Hodaie M, Lozano AM, Fasano A. Systematic review of hardware-related complications of Deep Brain Stimulation: Do new indications pose an increased risk? Brain Stimul. 2017;10:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhidayasiri R, Garcia Ruiz PJ, Henriksen T. Practical management of adverse events related to apomorphine therapy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;33 Suppl 1:S42–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lang AE, Rodriguez RL, Boyd JT, Chouinard S, Zadikoff C, Espay AJ, et al. Integrated safety of levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel from prospective clinical trials. Mov Disord. 2016;31:538–546. doi: 10.1002/mds.26485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Outpatient and ambulatory care settings: Responding to community transmission of COVID-19 in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2020 [updated 2020; cited]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ambulatory-care-settings.html.

- 63.Schneider RB, Biglan KM. The promise of telemedicine for chronic neurological disorders: the example of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:541–551. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dorsey ER, Deuel LM, Voss TS, Finnigan K, George BP, Eason S, et al. Increasing access to specialty care: a pilot, randomized controlled trial of telemedicine for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1652–1659. doi: 10.1002/mds.23145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cubo E, Gabriel-Galan JM, Martinez JS, Alcubilla CR, Yang C, Arconada OF, et al. Comparison of office-based versus home Web-based clinical assessments for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27:308–311. doi: 10.1002/mds.24028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abdolahi A, Scoglio N, Killoran A, Dorsey ER, Biglan KM. Potential reliability and validity of a modified version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale that could be administered remotely. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abdolahi A, Bull MT, Darwin KC, Venkataraman V, Grana MJ, Dorsey ER, et al. A feasibility study of conducting the Montreal Cognitive Assessment remotely in individuals with movement disorders. Health Informatics J. 2016;22:304–311. doi: 10.1177/1460458214556373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dias AE, Limongi JC, Barbosa ER, Hsing WT. Voice telerehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease. Codas. 2016;28:176–181. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20162015161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Kolk NM, de Vries NM, Kessels RPC, Joosten H, Zwinderman AH, Post B, et al. Effectiveness of home-based and remotely supervised aerobic exercise in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:998–1008. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spear KL, Auinger P, Simone R, Dorsey ER, Francis J. Patient Views on Telemedicine for Parkinson Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9:401–404. doi: 10.3233/JPD-181557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scholthof KB. The disease triangle: pathogens, the environment and society. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:152–156. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]