Abstract

BACKGROUND

Ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) is a rare, autosomal recessive, multisystem disorder. Because most clinicians have low awareness of the disease, only scarce reports of AT exist in the literature, especially of cases with lymphoma/leukemia.

CASE SUMMARY

A 7-year-old girl with a history of recurrent respiratory tract infections was referred to our department because of unstable walking for 5 years and enlarged neck nodes for 2-mo duration. Physical examination revealed scleral telangiectasia and cerebellar ataxia. Elevated alpha-fetoprotein, decreased serum immunoglobulin, and decreased T cell function were the major findings of laboratory examination. Histological analysis of cervical lymph node biopsy was suggestive of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. Genetic examination showed heterozygous nucleotide variation of c.6679C>T and heterozygous nucleotide variation of c.5773 delG in the ATM gene; her parents were heterozygotes. The final diagnosis was AT with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians should strengthen their understanding of AT diseases. Gene diagnosis plays an important role in its diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Ataxia-telangiectasia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, Child, Case report, ATM gene

Core tip: Ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) is a rare, autosomal recessive, multisystem disorder. Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations of the ATM gene is the pathogenic factor and there is no specific treatment for AT. Through this study of a case of AT complicated with Hodgkin's lymphoma, it is suggested that clinicians should strengthen their understanding of AT diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) is a rare and complex neurocutaneous syndrome with a poor prognosis. For children with scleral telangiectasia, cerebellar ataxia, and recurrent respiratory tract infections, AT should be considered[1]. A case of AT complicated with Hodgkin's lymphoma was admitted to Linyi People's Hospital of Shandong in July 2019, which is reported as follows.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 7-year-old girl presented with a 5-year history of unstable walking and a 2-mo history of enlarged neck nodes.

History of present illness

The child developed appropriately until 2 years of age. Subsequently, the parents noticed that the child had frequent falls and unsteady gait. Her language and motor development lagged behind that of other children of the same age. Two months prior to clinical presentation, the child developed enlarged lymph nodes in the neck.

History of past illness

The child had a history of recurrent respiratory tract infections.

Personal and family history

The birth history and feeding history were uneventful. There was no history of similar illness in the family.

Physical examination upon admission

On examination, the child had cervical and submental mobile lymphadenophathy, with the largest being 22 mm × 11 mm in size. The patient had conjunctival telangiectasia, truncal ataxia, wide-base gait, unstable standing, widening roadbed, intension tremor, and dysdiadokinesia, suggestive of cerebellar ataxia.

Laboratory examinations

Investigations showed increased leukocyte count (13.36 × 109/L; normal range: 3.5-9.5 × 109/L), increased alpha-fetoprotein (323.91 IU/mL; normal: < 9.96 IU/mL), and reduced immunoglobulin A (IgA; < 0.25 g/L, normal range: 0.7-4 g/L), immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1.90 g/L; normal range: 7-16 g/L) and immunoglobulin M (IgM; 0.3 g/L; normal range: 0.4-2.3 g/L). Tests for cytomegalovirus-IgM and Epstein-Barr viral capsid antigen-IgM were positive; however, that for cytomegalovirus DNA was negative and for Epstein-Barr virus DNA was positive (1.25E5).

Imaging examinations

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed widened and deepened sulcus of bilateral cerebellar hemispheres, bilateral sinusitis, and a small effusion in the left mastoid process.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

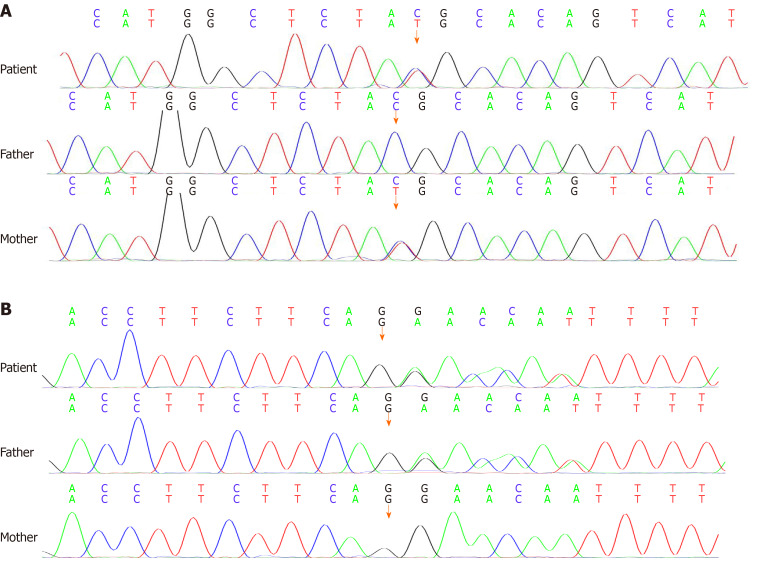

Cervical lymph node biopsy was suggestive of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma, and immunohistochemistry showed CD3 (-), CD20 (-), CD21 (+), Bcl-2 (-), CD30 (+), Ki67-MIB1 (80%), CD15 (-), Pax-5 (weak +), and MUM-1 (weak +). Gene examination showed the heterozygous nucleotide variation of c.6679C>T and heterozygous nucleotide variation of c.5773 delG. The parents were found to be heterozygotes (Figure 1). The final diagnosis was AT with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Figure 1.

Genetic findings. A: The missense variation of c.6679C>T in exon 46 was inherited from the mother, which was normal in the father; B: The shift mutation of c.5773delG in exon 39 was inherited from the father, which was normal in the mother.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, the child’s parents were unwilling to pursue further treatment due to the poor prognosis of the disease and financial constraints.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Follow-up was performed every 0.5 mo for 1 year. In the end, the child died of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome caused by repeated severe infections.

DISCUSSION

AT is a rare, autosomal recessive, multisystem disorder, involving nerves, blood vessels, the skin, and the endocrine and monocyte-macrophage system. The incidence is 1 in 40000 to 200000 people. In this case, the patient was first admitted to the Department of Neurology for ataxia at the age of 2 years, but lack of follow-up was the main cause of delayed diagnosis. In the admission described herein, the definite diagnosis was based upon scleral telangiectasia, cerebellar ataxia, recurrent respiratory tract infection, and gene mutation detection.

AT is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations of the ATM gene, which is located on chromosome 11q22-23 and encodes a large basic protein involved in many physiological processes, such as cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, and oxidative stress[2,3]. This patient harbors a compound heterozygous mutation of the ATM gene. The heterozygous nucleotide mutation of c.6679C>T (nucleotide in coding region 6679 changes from C to T) is a missense variation, resulting in the 2227 amino acid changing from arginine to cysteine; its pathogenicity has been reported in the literature[1]. The heterozygous nucleotide mutation of c.5773 delG (a G nucleotide deletion in the coding region at 5773) results in a frameshift mutation, in which the change of amino acid synthesis starts with glycine in the coding region at 1925 and terminates with the changed 12th amino acid. The above variants, inherited from parents separately, accord with autosomal recessive inheritance and might affect the function of proteins, which is implicated as the pathogenic variation leading to the disease.

AT is a multisystem disorder[4,5], and ataxia is one of the early clinical manifestations. Although the children usually start walking at a normal age, they wobble or sway when walking, standing still, or sitting, and may appear almost as if they are drunk. Generally, many patients are confined to a wheelchair in their teens[6]. Telangiectasia is usually appreciated around 3-6 years of age and occurs successively in the conjunctiva, eyelid, cheek, and skin folds of limbs. Some children have frequent infections of the respiratory tract (ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia) because of susceptibility to viruses and bacteria. Abnormalities in cell cycle regulation and cell apoptosis caused by the ATM gene mutation lead to immunodeficiency, high sensitivity to radiation, and increased tumor susceptibility[7,8]. A variety of laboratory abnormalities occur in most people with AT, including low levels of one or more classes of immunoglobulins, low numbers of lymphocytes in the blood, and increasing alpha-fetoprotein levels in serum. At present, due to the widespread use of antibiotics, children with AT have a significantly reduced chance of dying from infectious diseases in their early years and their survival time is significantly prolonged, which has significantly increased the incidence of lymphoma, leukemia, and other tumors.

The main manifestations of our case were cerebellar ataxia, conjunctival telangiectasia, poor immunity, elevated alpha-fetoprotein, decreased serum immunoglobulin, and decreased T cell function, which highly matched with the core symptoms of AT. The literature reports that 10%-25% of AT patients may develop malignant tumors, of which 85% are lymphoma and leukemia[9]. In our case, the child suffered secondary Hodgkin's lymphoma, which is characterized by swollen cervical lymph nodes and may be accompanied by persistent or periodic fever. If the swollen lymph nodes compress nerves, it may cause pain. Its diagnosis relies on lymph node puncture smear and pathological biopsy. About 50% of Reed-Sternberg cells of classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma show Epstein-Barr virus genome fragments, and positive expression of CD30 antigen is an important immune marker[10].

Currently, there is no specific treatment for AT[11]. Treatment includes symptomatic supportive treatment, improvement of immune status, and prevention and control of infections. For AT patients with secondary tumors, careful chemotherapy and radiation therapy are required but the treatment effect is not as good as that for the primary tumor, and the risk of infection is also increased. The prognosis of the disease is poor, with most patients dying from severe pulmonary infection or cancer[12].

CONCLUSION

Through the study of this case, it is suggested that clinicians should strengthen their understanding of AT diseases and that gene diagnosis plays an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of rare genetic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the patient and her parents for allowing publication of this rare case report.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The patient’s guardian agreed to the genetic test and signed a written informed consent form.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 2, 2020

First decision: April 22, 2020

Article in press: May 16, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dhanushkodi M, Moustaki M S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Xiao-Ling Li, Department of Pediatrics (III), The Linyi People’s Hospital, Linyi 276000, Shandong Province, China.

Yi-Lin Wang, Department of Pediatrics (III), The Linyi People’s Hospital, Linyi 276000, Shandong Province, China. lxl801527@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Sandoval N, Platzer M, Rosenthal A, Dörk T, Bendix R, Skawran B, Stuhrmann M, Wegner RD, Sperling K, Banin S, Shiloh Y, Baumer A, Bernthaler U, Sennefelder H, Brohm M, Weber BH, Schindler D. Characterization of ATM gene mutations in 66 ataxia telangiectasia families. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:69–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paz A, Brownstein Z, Ber Y, Bialik S, David E, Sagir D, Ulitsky I, Elkon R, Kimchi A, Avraham KB, Shiloh Y, Shamir R. SPIKE: a database of highly curated human signaling pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D793–D799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumada S. [Ataxia Telangiectasia] Brain Nerve. 2019;71:380–382. doi: 10.11477/mf.1416201280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teive HA, Moro A, Moscovich M, Arruda WO, Munhoz RP, Raskin S, Ashizawa T. Ataxia-telangiectasia - A historical review and a proposal for a new designation: ATM syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2015;355:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perlman SL, Boder Deceased E, Sedgewick RP, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;103:307–332. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-51892-7.00019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nissenkorn A, Levy-Shraga Y, Banet-Levi Y, Lahad A, Sarouk I, Modan-Moses D. Endocrine abnormalities in ataxia telangiectasia: findings from a national cohort. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:889–894. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suarez F, Mahlaoui N, Canioni D, Andriamanga C, Dubois d'Enghien C, Brousse N, Jais JP, Fischer A, Hermine O, Stoppa-Lyonnet D. Incidence, presentation, and prognosis of malignancies in ataxia-telangiectasia: a report from the French national registry of primary immune deficiencies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:202–208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beraldi R, Meyerholz DK, Savinov A, Kovács AD, Weimer JM, Dykstra JA, Geraets RD, Pearce DA. Genetic ataxia telangiectasia porcine model phenocopies the multisystemic features of the human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:2862–2870. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vassilakopoulos TP, Chatzidimitriou C, Asimakopoulos JV, Arapaki M, Tzoras E, Angelopoulou MK, Konstantopoulos K. Immunotherapy in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Present Status and Future Strategies. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1071. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhary MW, Al-Baradie RS. Ataxia-telangiectasia: future prospects. Appl Clin Genet. 2014;7:159–167. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S35759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Os NJH, Jansen AFM, van Deuren M, Haraldsson A, van Driel NTM, Etzioni A, van der Flier M, Haaxma CA, Morio T, Rawat A, Schoenaker MHD, Soresina A, Taylor AMR, van de Warrenburg BPC, Weemaes CMR, Roeleveld N, Willemsen MAAP. Ataxia-telangiectasia: Immunodeficiency and survival. Clin Immunol. 2017;178:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]