Abstract

This study evaluates the patient experience during virtual otolaryngology clinic visits implemented during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Patient satisfaction surveys were queried from January 1, 2020, to May 1, 2020, for both telehealth and in-person visits. A descriptive analysis of the question responses was performed. There were 195 virtual and 4013 in-person visits with surveys completed in this time period. Ratings related to provider-patient communication were poor for virtual visits. Telehealth has become the new norm for most health care providers in the United States. This study demonstrates some of the initial shortcomings of telehealth in an otolaryngology practice and identifies challenges with interpersonal communication that may need to be addressed as telehealth becomes increasingly prevalent.

Keywords: telehealth, patient satisfaction, patient experience, virtual medicine, telemedicine, COVID-19

With the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, otolaryngologists, among other specialties, implemented telehealth strategies to adapt to physical distancing guidelines.1-9 Previous studies demonstrated telehealth to be cost-effective and useful.10-14 Given the perceived utility of remote care under these circumstances, policy changes have readily promoted its increased use across specialties.15

Implementing telehealth on a wide scale presents unique challenges to otolaryngologists given routine use of endoscopy and microscopy.16 However, recent efforts have demonstrated the promising potential of new techniques and tools to evaluate these patients.16-20 As telehealth inevitably becomes prevalent from improved technological access and response to the pandemic, there is an emerging knowledge gap of how these rapidly evolving practices are addressing patient needs and concerns.21

The main objective of this study was to assess the virtual visit experience from the patient’s perspective relative to more traditional in-person clinic visits in the same time period.

Methods

The National Research Corporation is currently used to administer and collect the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (GC CAHPS) survey across outpatient clinics.22 This has continued during the recent conversion to telehealth, although with slight alterations to suit the different platform. Providers have used Doximity Dialer23 videoconferencing software for most visits, with Facetime24 as an alternative. Virtual visit time slots were doubled compared to in-person time slots to allot for technological issues and potential inefficiencies in communication. Cedars-Sinai internal institutional review board exemption was granted for this study since no personal health information was accessed. Patient satisfaction metrics were queried from January 1, 2020, to May 1, 2020, for both telehealth and in-person visits for the 16 otolaryngology providers in our practice. Questions contained in the respective surveys and mean scores are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 . Data from individual surveys were not available, so standard deviation and error were not calculable. Statistical analysis between telehealth and in-person visits was also not calculable, so a descriptive analysis of the results was performed.

Table 1.

Virtual Visit Patient Satisfaction Survey Results.a

| Question | No. | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Did this provider seem to know important information about your medical history? | 173 | 64.7 |

| Did this provider listen carefully to you? | 186 | 82.3 |

| Would you recommend this provider’s office to your family and friends? | 176 | 85.8 |

| Did this provider give you easy to understand information about these health questions or concerns? | 188 | 75.5 |

| Using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst provider possible and 10 is the best provider possible, what number would you use to rate this provider? | 178 | 84.8 |

| Method of connecting to the provider was easy. | 192 | 65.6 |

| Overall quality of the video or call. | 191 | 68.1 |

| Overall trust for the provider. | 184 | 81.5 |

| Amount of waiting before talking to the provider. | 195 | 66.7 |

| Know what to do if more questions. | 181 | 65.2 |

For each question, patients were asked to rate their experience from 0 to 100.

Table 2.

In-Person Visit Patient Satisfaction.a

| Question | No. | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Did this provider seem to know important information about your medical history? | 4013 | 87.6 |

| Did this provider listen carefully to you? | 4013 | 95.9 |

| Would you recommend this provider’s office to your family and friends? | 4013 | 94.5 |

| Did this provider give you easy to understand information about these health questions or concerns? | 4013 | 95.1 |

| Using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst provider possible and 10 is the best provider possible, what number would you use to rate this provider? | 4013 | 89.9 |

| Did this provider spend enough time with you? | 4013 | 93.7 |

| Did this provider show respect for what you had to say? | 4013 | 96.2 |

For each question, patients were asked to rate their experience from 0 to 100.

Results

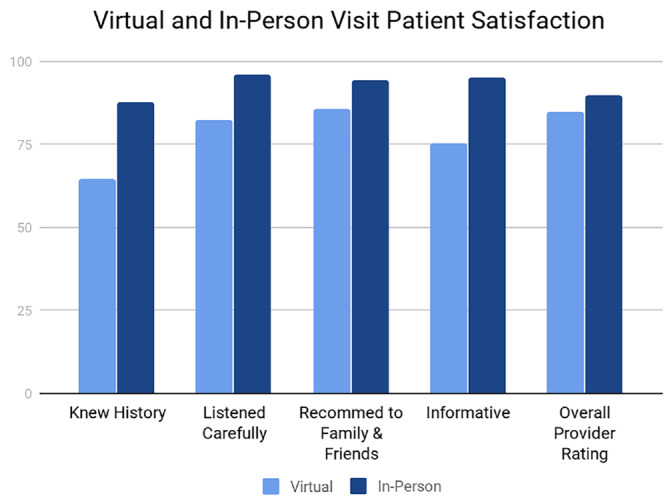

During the study time period, there were 195 virtual visits and 4013 in-person visits with survey results. Results are displayed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Figure 1 shows results from overlapping questions.

Figure 1.

Virtual and in-person visit patient satisfaction survey results for overlapping questions.

Despite allotting double time per visit, scores across the survey were surprisingly low in certain categories. Ratings for ease of connection to the provider (65.6), video quality (68.1), wait times (66.7), knowledge of medical history (64.7), and patient understanding of what to do for follow-up questions (65.2) were poor for virtual visits. Ratings for trust in the provider, provider listening, likelihood to recommend, and overall rating were higher.

Discussion

Physical distancing is critical to curtail the spread of COVID-19.25 Many providers have transitioned most of their clinic visits to virtual visits,26 and these efforts have been bolstered by policy changes by reimbursing entities.27 With so many providers now relying on this method to deliver care, it is critical to determine the efficacy of these services during and after the pandemic.28

Best practices must be established to optimize quality of care in the remote setting.29 There is a particular need to evaluate the subjective patient experience during these virtual visits to determine its impact on the patient-physician relationship.21 Potential harms of relying on virtual visits include diagnostic challenges from the provider’s perspective but also suboptimal interpersonal communication. Although previous studies have described positive patient satisfaction for telehealth services, its applicability in otolaryngology is less known.30

In this study, we report poor ratings on questions relevant to interpersonal communication from patients who underwent virtual visits. Although speculative at best, we postulate that the patient’s subjective experience was influenced negatively by this introduction of telecommunication. Despite doubling the length of visits, patients noted difficulties in communication and longer wait times for their visit. The quality of the video was rated quite low by patients and reflects several variables, including the Internet speeds of each individual and the server speed of the platform’s server. Audio-video lag is especially frustrating during provider-patient conversation, resulting in an individual talking over the other or missing important details. Patients were not queried about Internet speeds, but this is a consideration that might affect the patient experience. Wait times were also poorly rated for video visits. Virtual check-in to complete various forms may take longer for patients and staff to accomplish. In addition, many of these issues may be a result of providers initially adopting telehealth without formal training or equipment and adapting to these new changes quickly. Over time, it is reasonable to expect patient satisfaction to increase as technical difficulties are optimized.

As many otolaryngologists continue telehealth in their practices moving forward, the need remains to determine how these new practice patterns affect the patient experience. Despite the noted advantages that telehealth provides, we observe that there is room for improvement with regards to patient satisfaction in delivering care remotely.

Our study is limited to the experiences of the providers and patients at our single institution during this limited time period, and therefore selection bias may skew the results of this initial report. In addition, statistical analysis could not be performed to directly compare virtual and in-person visits. Future work should elucidate whether patient attitudes change over time as telehealth becomes a more familiar medium.

Conclusion

Due to the COVID-19 crisis, telehealth has abruptly become the new norm for most health care providers in the United States. This study demonstrates some of the initial shortcomings of telehealth in an otolaryngology practice.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Kyohei Itamura, data interpretation, initial manuscript creation, manuscript revision; Franklin L. Rimell, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript revision; Elisa A. Illing, data interpretation, initial manuscript creation, manuscript revision; Thomas S. Higgins, data interpretation, initial manuscript creation, manuscript revision; Jonathan Y. Ting, data interpretation, initial manuscript creation, manuscript revision; Matthew K. Lee, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript revision; Arthur W. Wu, study concept creation, data collection, data interpretation, initial manuscript creation, manuscript revision.

Disclosures: Competing interests: Thomas S. Higgins, Sanofi/Regeneron (consultant, speaker), Optinose (investigator/research grant, speaker), Genentec (consultant), Gossamer (investigator/research grant), and Intersect (investigator/research grant); Arthur W. Wu, Sanofi/Regeneron (medical advisory board, speaker), Optinose (investigator, speaker), and Gossamer (investigator).

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: None.

References

- 1. Liu R, Sundaresan T, Reed ME, Trosman JR, Weldon CB, Kolevska T. Telehealth in oncology during the COVID-19 outbreak: bringing the house call back virtually [published online May 4, 2020]. JCO Oncol Pract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee AKF, Cho RHW, Lau EHL, et al. Mitigation of head and neck cancer service disruption during COVID-19 in Hong Kong through telehealth and multi-institution collaboration [published online May 1, 2020]. Head Neck. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: A systematic review based on current evidence [published online May 5, 2020]. BMC Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lonergan PE, Washington SL, Branagan L, et al. Rapid utilization of telehealth in a comprehensive cancer center as a response to COVID-19 [published online April 15, 2020]. MedRxIV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas E, Gallagher R, Grace SL. Future-proofing cardiac rehabilitation: transitioning services to telehealth during COVID-19 [published online April 23, 2020]. Eur J Prevent Cardiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rismiller K, Cartron AM, Trinidad JCL. Inpatient teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online May 13, 2020]. J Dermatolog Treat. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boehm K, Ziewers S, Brandt MP, et al. Telemedicine online visits in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic: potential, risk factors, and patients’ perspective [published online April 27, 2020]. Eur Urol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hemingway JF, Singh N, Starnes BW. Emerging practice patterns in vascular surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online April 30, 2020]. J Vasc Surg. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saleem SM, Pasquale LR, Sidoti PA, Tsai JC. Virtual ophthalmology: telemedicine in a Covid-19 era [published online April 30, 2020]. Am J Ophthalmol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaw D, Anderson A, Hernandez C, Padilla J, Royer J, Saulog C. Use of telehealth during physical rehabilitation for patients with CHF: a systematic review. Innovation Aging. 2017;1(suppl 1):969-969. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Min J, Khuri J, et al. Effectiveness of mobile health interventions on diabetes and obesity treatment and management: systematic review of systematic reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(4):e15400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xie W, Dai P, Qin Y, Wu M, Yang B, Yu X. Effectiveness of telemedicine for pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: an updated meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials with trial sequential analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsou C, Robinson S, Boyd J, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telehealth in rural and remote emergency departments: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nangrani N. Outcomes of telehealth in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Diabetes 2018. l;67(Supplement 1). [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Medical Association. CMS payment policies & regulatory flexibilities during COVID-19 emergency. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare/cms-payment-policies-regulatory-flexibilities-during-covid-19. Accessed May 5, 2020.

- 16. Goldenberg D, Wenig BL. Telemedicine in otolaryngology. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23(1):35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCool RR, Davies L. Where does telemedicine fit into otolaryngology? An assessment of telemedicine eligibility among otolaryngology diagnoses. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(4):641-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garritano FG, Goldenberg D. Successful telemedicine programs in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(6):1259-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Setzen M, Svider PF, Pollock K. COVID-19 and rhinology: a look at the future [published online April 15, 2020]. Am J Otolaryngol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller LE, Buzi A, Williams A, et al. Reliability and accuracy of remote fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy in the pediatric population [published online April 13, 2020]. Ear Nose Throat J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pappot N, Taarnhøj GA, Pappot H. Telemedicine and e-health solutions for COVID-19: patients’ perspective [published online April 24, 2020]. Telemed J E Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS Clinician & Group Survey 2019, August Accessed May 6, 2020 https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/cg/index.html

- 23. Dialer D. Doximity dialer for iPhone and Android. Accessed May 6, 2020 https://www.doximity.com/clinicians/download/dialer

- 24. Facetime. Facetime on the App Store. Accessed May 6, 2020 https://apps.apple.com/us/app/facetime/id1110145091

- 25. Sen-Crowe B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: staying home save lives [published online April 2, 2020]. Am J Emerg Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic J Am Coll Surg 2020;S1072-7515(20)30375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physicians and other clinicians: CMS flexibilities to fight COVID-19. Accessed May 6, 2020 https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-19-physicians-and-practitioners.pdf

- 28. Pollock K, Setzen M, Svider PF. Embracing telemedicine into your otolaryngology practice amid the COVID-19 crisis: an invited commentary [published online April 15, 2020]. Am J Otolaryngol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prasad A, Brewster R, Newman JG, Rajasekaran K. Optimizing your telemedicine visit during the COVID-19 pandemic: practice guidelines for head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1317-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]