Abstract

Background

A small percentage of incomplete optical colonoscopies (OCs) are the result of an obstructing tumor. According to current guidelines, CT colonography (CTC) is performed to prevent missing a synchronous tumor. The aim of this study was to evaluate how frequently a synchronous tumor was found on CTC and how often this led to a change in the surgical plan.

Methods

In this retrospective study, a total of 267 patients underwent CTC after an incomplete OC as a result of an obstructing colorectal carcinoma (CRC). Among them, 210 patients undergoing surgery met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The OC report, CTC report and surgical report of these patients were retrospectively evaluated for the presence of synchronous tumors using surgery and post-operative colonoscopy as the gold standard.

Results

Six of the 210 patients (2.9%) showed signs of a synchronous CRC proximal to the obstructing tumor on CTC. In three of these patients, a synchronous CRC was confirmed during surgery. All these tumors caused a change in the surgical plan. Three out of the six tumors found on CTC were found to be large, non-malignant polyps. All these polyps were located in the same segment as the obstructing tumor and therefore did not alter the surgical plan.

Conclusion

In patients with obstructing CRC, the frequency of synchronous CRCs proximal to this lesion is low. Performing a CTC leads to a change in surgical plan based on the presence of these synchronous tumors in 1.4% of the cases. CTC should be employed as a one-stop shop in patients with an obstructing CRC.

Keywords: CT colonography, optical colonoscopy, colorectal carcinoma, synchronous tumor, pre-operative evaluation

Introduction

Worldwide, colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third most common cancer in men and the second in women [1]. Optical (endoscopic) colonoscopy (OC) is currently the gold standard for the detection of CRCs. However, 10–13% of all colonoscopies are incomplete [2,3]. These colonoscopies are predominantly incomplete due to looping of the colon, decreased colon mobility or poor bowel preparation. Only 7% of the incomplete colonoscopies are the result of an obstructing tumor [3].

In patients who have an incomplete OC due to an obstructing CRC, the presence of a synchronous tumor should be excluded. Large population-based studies show that close to 4% of all CRC patients have synchronous colorectal tumors [4,5]. Of these synchronous tumors, 34–46% are located in a different surgical segment than the index tumor [4,5]. In general, these synchronous tumors are significantly smaller than solitary tumors and index tumors [6]. As a result of the high accuracy of computed tomography colonography (CTC) for both CRC and large polyps [7–9], the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) recommend to perform a CTC after an incomplete colonoscopy resulting from an obstructing CRC [10].

In this study, we examined the added value of performing a CTC in patients with an incomplete colonoscopy resulting from an obstructing CRC, by calculating the frequency of synchronous tumors and by evaluating how frequently performing a CTC led to a change of the surgical plan.

Materials and methods

This retrospective observational cohort study was performed in VieCuri Medical Centre, Venlo, The Netherlands—a large non-academic hospital. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committees.

Patients

Between January 2007 and February 2017, a total of 267 patients underwent CTC because they had a histopathologically proven obstructing CRC on OC. Fifty-seven patients who did not undergo surgical resection were excluded from this study, as it was impossible to confirm or exclude the presence of a synchronous tumor in these patients. Most of these patients did not undergo surgical resection as a result of present metastases at the time of diagnosis. The remaining 210 patients were all included in this study.

OC protocol

Bowel preparation consisted of a low-fiber diet for 72 hours, with Bisocadyl 10 mg in the morning and one sachet of Picoprep® (Sodium picosulfate; Magnesium oxide; Citric acid, Ferring B.V.) in the evening before OC. In addition, the patient consumed 2 liters of clear liquid. Another sachet of Picoprep® was taken 4 hours prior to the OC and another 2 liters of clear liquid was taken 3 hours before the examination. Klean-Prep® (Polyethylene Glycol and Electrolytes, Norgine B.V.) was used instead of Picoprep® if the patient had a kreatinine clearance <30 mmol/L. Patients were sedated with Fentanyl 0.1 mg/2 mL or Midazolam 5 mg/1 mL until conscious sedation was reached. Colonic distension was obtained by inflating the bowel with carbon dioxide. Once a lesion suspected of being a carcinoma was identified, biopsies were taken for histopathological examination and the lesions were marked with a Spot Endoscopic Marker ™ (GI supply). A CRC was considered to be obstructing if the colonoscope was unable to pass the lesion. If the colonoscope was able to pass the lesion but could not reach cecal intubation, it was also excluded from this study. All colonoscopies were performed by experienced gastroenterologists or specialized nurses supervised by these gastroenterologists.

CTC protocol

In all patients, bowel preparation consisted of a low-fiber diet for 48 hours, with 150 mL magnesium citrate in the morning and Bisocadyl 10 mg in the morning as well as in the evening on the day before CTC was performed. Fecal tagging was performed with Barium Sulphate, which was ingested the evening before the examination. The CTC was performed by trained technicians on a 64-MDCT (Brilliance 64, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) or on 128 MDCT (Somatom, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), imaging in both supine and prone positions. Colonic distension was reached by administering 1 mL scopolamine butyl 20 mg/mL or, when this was contraindicated, 1 mL glucagon 1 mg/mL intravenously and subsequently automated low-pressure delivery of carbon dioxide by a colon insufflator device (PROTOCO2L, E-Z-EM). Intravenous contrast (120 mL Omnipaque 300 mg/mL) was administered, allowing evaluation of distant metastases. The supine scan was made in portal venous phase. Imaging data were reviewed by one of four trained radiologists on a dedicated 3D workstation (Extended Brilliance Workspace 3.0 or 4.0, Philips Healthcare; Best, The Netherlands) using a 3D analysis with endoview, filet view and computer-assisted detection (CAD), in addition to the traditional 2D images.

Pre-operative imaging

Patients who had an incomplete OC resulting from an obstructing tumor were preoperatively analysed in the following week. In case the tumor was located in the colon, a chest X-ray and a contrast-enhanced CTC were performed. In case the tumor was located in the rectum, an MRI of the rectum for local staging was added. If the gastroenterologist was certain the tumor was located in the cecum or ascending colon (including hepatic flexure), no additional CTC was performed, as it would not change the surgical procedure. If the gastroenterologist was not certain whether the tumor was located in the right hemicolon, a CTC was performed preoperatively to verify tumor localization.

Statistical analyses

If CTC showed a synchronous tumor that was missed on OC as a result of an obstructing CRC, either surgery or post-operative colonoscopy was performed to confirm the presence of a synchronous tumor. A change in the primary surgical plan was defined as a surgical procedure other than the one that would have been performed for the obstructing CRC only. Descriptive statistics were performed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences version 22.0 (SPSS).

Results

A total of 210 patients met the in- and exclusion criteria. Mean age of the patients was 73 years (range, 38–99 years) and 50.0% were male (n = 105).

CTC was unable to evaluate the colon proximal to an obstructing tumor in 10 cases (4.8%). This resulted mainly from an inability to insufflate the colon proximal to a pinpoint stenosis. In 2 of these 10 patients, a right hemicolectomy was performed because the obstructing tumor was located in the right hemicolon. In four of these patients, post-operative colonoscopy did not show signs of a tumor proximal to the anastomosis. The other four patients did not receive post-operative colonoscopy because the patient was diagnosed with distant metastases, because the patient deceased or because of non-adherence.

In 49 out of 210 cases (23.3%), CTC was able to evaluate the colon proximal to an obstructing tumor but CTC quality was suboptimal. This was caused by inadequate bowel distension (n = 20), fecal contamination (n = 19) or a combination of both (n = 10). Twenty-two of the 49 patients did not undergo a post-operative colonoscopy, mainly because, in these patients, the tumor had already metastasized. In 27 of these 49 cases, a post-operative colonoscopy was performed. In one of these cases, a tumor proximal to the obstructing lesion was found on post-operative OC that pre-operative CTC did not locate. This patient had an obstructing sigmoid tumor (pT4N0). As CTC could not locate the synchronous tumor preoperatively in this patient, a sigmoidectomy was performed. At post-operative colonoscopy (9 months later), a second tumor in the ascending colon (pT3N0) was found. Based on this finding, a subtotal colectomy was performed.

In 151 of the 210 patients (71.9%), CTC quality was optimal. In 88 of these 151 cases, a post-operative colonoscopy was performed. None of these patients had a synchronous tumor that was not located on CTC. Sixty-three patients did not undergo post-operative colonoscopy. This occurred mainly because the patient was diagnosed with metastases, because the patient deceased or because the follow-up time after surgery was less than 12 months.

According to surgery, the obstructing tumors were located in the rectum (n = 21), sigmoid colon (including rectosigmoid junction) (n=106), descending colon (including splenic flexure) (n=25), transverse colon (n=12), ascending colon (including hepatic flexure) and cecum (n=46). There were 14 synchronous CRCs present in these 210 patients (6.7%). CTC located all but one of these synchronous tumors. Ten out of these 14 CRCs were distal to the obstructing CRC and were also shown on OC.

Six patients (2.9%) showed signs of a synchronous CRC proximal to the obstructing tumor on CTC. In three of these patients (1.4%), a synchronous CRC was confirmed during surgery. These CRCs were located in a different surgical segment as the obstructing carcinoma, and thus changed the surgical plan (Figure 1). In three out of six tumors found on CTC (1.4%), the tumors turned out to be large non-malignant polyps of respectively 2, 2 and 3 cm instead of CRCs. These polyps were located in the same surgical segment as the obstructing CRC and did not alter the surgical plan. A summary of the characteristics of all synchronous tumors proximal to an obstructing CRCs can be found in Table 1.

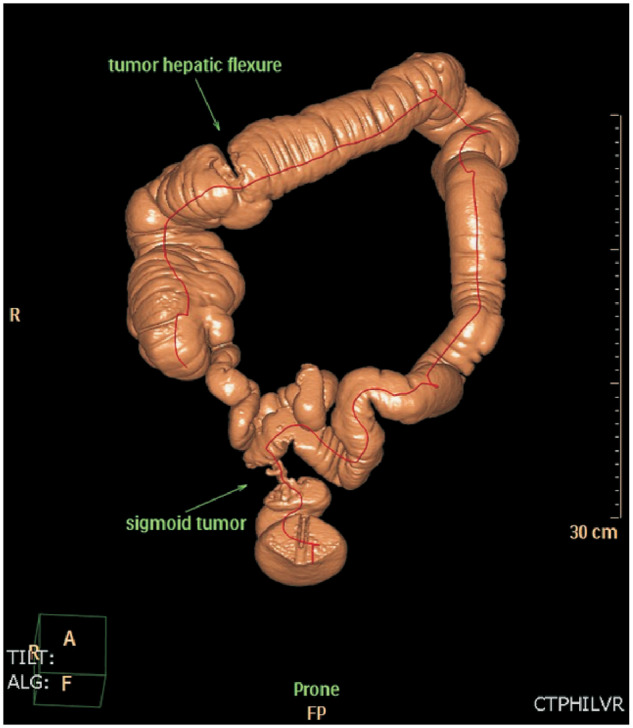

Figure 1.

A patient who underwent optical colonoscopy was found to have an obstructing T4 tumor in the sigmoid colon. A CT colonography that was performed to rule out synchronous tumors proximal to the obstructing tumor showed a synchronous tumor in the hepatic flexure. Based on this information, a subtotal colectomy was performed. Surgery confirmed the presence of a synchronous tumor in the hepatic flexure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of synchronous tumors found on CT colonography

| Tumor number | Localization of obstructing tumor | Localization of synchronous tumor | TNM stage of obstructing tumor | TNM stage of synchronous tumor | Modification of surgical plan | Type of surgery performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Sigmoid colon | Cecum | T3N0 | T1N0 | Yes | Sigmoid resection and ileocecal resection |

| #2 | Sigmoid colon | Hepatic flexure | T4N1 | T2N0 | Yes | Subtotal colectomy |

| #3 | Sigmoid colon | Descending colon | T4N1 | T2N1 | Yes | Extended left-sided hemi colectomy |

| #4 | Rectum | Sigmoid colon | T3N0 | Advanced adenoma 2 cm | No | Low anterior resection |

| #5 | Hepatic flexure | Cecum | T3N0 | Advanced adenoma 3 cm | No | Right-sided hemi colectomy |

| #6 | Rectum | Sigmoid colon | T3N0 | Advanced adenoma 2 cm | No | Low anterior resection |

Fifteen out of 210 patients had 23 advanced polyps (polyps >10 mm) proximal to the obstructing tumor on CTC. Nine out of these 15 patients underwent post-operative surveillance colonoscopy (60%). The mean time between surgery and postsurgical colonoscopy was 7 months (range 1–12 months). None of these polyps was found to be malignant during post-operative colonoscopy or following surgical resection. All of the polyps could be endoscopically removed.

Discussion

In our study, the pre-operative identification of synchronous CRCs by CTC caused a change in the primary surgical plan in 1.4% of the cases. Although the prevalence of synchronous tumors proximal to an obstructing tumor is low, pre-operative detection of synchronous tumors is essential, as it prevents secondary surgery and simultaneously might prevent development to an advanced stage of the synchronous tumor. In the Netherlands, the number of newly diagnosed patients with colorectal cancer was 15 273 in 2016 [11]. Approximately 16% of these tumors are obstructing [12]. If we extrapolate our findings, secondary surgery could have been prevented in 34 patients during that year. Furthermore, CTC could delay the post-operative interval of performing an OC. Current guidelines recommend performing a post-operative OC 3 months after resection to exclude the presence of synchronous tumors [13]. In our study, the colon was already optimally visualized proximal to the obstructing tumor in 71.9% of the cases. In these cases, due to the high negative predictive value of CTC for synchronous advanced neoplasia [9], performing an OC could be delayed to 12 months after resection.

We found that, in 1.4% of the cases, CTC caused a change in the primary surgical plan as a result of the presence of a synchronous carcinoma proximal to the obstructing tumor, compared to 1.9–6.7% found in previous studies [14–16]. This relatively low percentage compared to other studies can be explained by variance due to the low prevalence of synchronous tumors combined with the small sample sizes in all studies. Furthermore, in our study, 45 patients with an obstructing tumor in the cecum and ascending colon were included. Finding a synchronous tumor proximal to this obstructing tumor would never lead to a change in the surgical plan based on this finding, as a right hemicolectomy would be performed either way. These patients underwent CTC because tumor localization of the obstructing tumor was uncertain on OC, which is a known flaw of OC [17].

Three patients in our study were found to have a large lesion at CTC, which was interpreted as malignancy but turned out to be a large non-malignant adenoma instead. CTC has a limited capability in differentiating advanced adenomas from CRCs [9]. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of CTC might be lower in obstructing CRC due to inadequate bowel distension and fecal contamination (in our study, 28.1% of the CTCs had suboptimal or poor quality) [9]. This might lead to unnecessary resections, as most polyps can be endoscopically removed [18,19]. On the other hand, when a polyp cannot be removed endoscopically, secondary surgery is needed [19]. If there is any doubt on CTC whether a lesion is a CRC or a large polyp, an intra-operative OC can be performed.

When a CRC is detected, a contrast-enhanced CT abdomen is usually performed to exclude metastases. Huisman et al. found in their study that two out of three synchronous tumors found on CTC were also visible on conventional staging CT abdomen [14]. However, the overall sensitivity and negative predictive value of abdominal CT following an incomplete OC are lower than that of CTC [9,20]. This can be explained by the significantly smaller size of synchronous tumors compared to index tumors [6,20–22], which makes it particularly hard for conventional CT abdomen to identify the lesion. Since our institution always performs a contrast-enhanced CTC in order to localize potential metastases and in addition to rule out the presence of synchronous tumors, it was not possible to evaluate whether synchronous tumors would also have been identified at a conventional abdominal CT.

Pre-operative evaluation of the colon by CTC does not only allow the detection of synchronous tumors; it also enables the correct visualization of the pre-operative localization of the tumor. In terms of tumor localization, CTC compares favorably with respect to optical colonoscopy [15–17,23–25] and a change in surgical plan based on CTC localization is required in 4–12% of the performed CTCs [15–17]. In a recent study in our patient population, we showed that overall CTC had a lower segmental localization error rate than OC and that this difference was specifically prominent for descending colon tumors [17]. CTC optimizes pre-operative information given to the patient and allows the surgeon to assess the length and the quality of the colon (e.g. extensive diverticulosis or a dolichocolon), which might influence resection type and estimated operation time. In addition, in case of contrast-enhanced CTC, information on the anatomy of mesenteric vessels in relation to the tumor can be obtained simultaneously [26,27].

In conclusion, in patients with obstructing CRC, the frequency of synchronous CRC is low. Performing a CTC leads to a change in the surgical plan based on the presence of these synchronous tumors in 1.4% of the cases. The added clinical value of performing CTC preoperatively, however, does not only lie within the ability of CTC to find a synchronous tumor; pre-operative evaluation of the colon also grants the surgeon the ability to evaluate the length and quality of the colon and the ability to better localize the tumor(s) preoperatively. For these reasons, CTC should be employed as a one-stop shop in patients with obstructing CRC.

Conflict of interest statement: none declared.

References

- 1.GLOBACAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr (21 April 2017, date last accessed).

- 2. Shah HA, Paszat LF, Saskin R. et al. Factors associated with incomplete colonoscopy: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aslinia F, Uradomo L, Steele A. et al. Quality assessment of colonoscopic cecal intubation: an analysis of 6 years of continuous practice at a university hospital. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Latournerie M, Jooste V, Cottet V. et al. Epidemiology and prognosis of synchronous colorectal cancers. Br J Surg 2008;95:1528–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mulder SA, Kranse R, Damhuis RA. et al. Prevalence and prognosis of synchronous colorectal cancer: a Dutch population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol 2011;35:442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oya M, Takahashi S, Okuyama T. et al. Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: clinico-pathological features and prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2003;33:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pickhardt PJ, Hassan C, Halligan S. et al. Colorectal cancer: CT colonography and colonoscopy for detection—systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 2011;259:393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simons PC, Van Steenbergen LN, De Witte MT. et al. Miss rate of colorectal cancer at colonography in average-risk symptomatic patients. Eur Radiol 2013;23:908–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park SH, Lee JH, Lee SS. et al. CT colonography for detection and characterisation of synchronous proximal colonic lesions in patients with stenosing colorectal cancer. Gut 2012;61:1716–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spada C, Stoker J, Alarcon O. et al. Clinical indications for computed tomographic colonography: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) Guideline. Eur Radiol 2015;25:331–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. https://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl (29 October 2017, date last accessed).

- 12. Serpell JW, McDermott FT, Katrivessis H. et al. Obstructing carcinomas of the colon. Br J Surg 1989;76:965–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA. et al. Colonoscopy surveillance after colorectal cancer resection: recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:337–46;quiz 347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huisman JF, Leicher LW, de Boer E. et al. Consequences of CT colonography in stenosing colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim JH, Kim WH, Kim TI. et al. Incomplete colonoscopy in patients with occlusive colorectal cancer: usefulness of CT colonography according to tumor location. Yonsei Med J 2007;48:934–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flor N, Ceretti AP, Mezzanzanica M. et al. Impact of contrast-enhanced computed tomography colonography on laparoscopic surgical planning of colorectal cancer. Abdom Imaging 2013;38:1024–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Offermans T, Vogelaar FJ, Aquarius M. et al. Preoperative segmental localization of colorectal carcinoma: CT colonography vs. optical colonoscopy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017;43:2105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doniec JM, Löhnert MS, Schniewind B. et al. Endoscopic removal of large colorectal polyps: prevention of unnecessary surgery? Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46:340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Binmoeller KF, Bohnacker S, Seifert H. et al. Endoscopic snare excision of ‘giant’ colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;43:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pang EJ, Liu WJ, Peng JY. et al. Prediction of synchronous colorectal cancers by computed tomography in subjects receiving an incomplete colonoscopy: a single-center study. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato T, Alonso S, Muto Y. et al. Clinical characteristics of synchronous colorectal cancers in Japan. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lam AK, Carmichael R, GertraudBuettner P. et al. Clinicopathological significance of synchronous carcinoma in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg 2011;202:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neri E, Turini F, Cerri F. et al. Comparison of CT colonography vs. conventional colonoscopy in mapping the segmental location of colon cancer before surgery. Abdom Imaging 2010;35:589–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cho YB, Lee WY, Yun HR. et al. Tumor localization for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. World J Surg 2007;31:1491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sali L, Falchini M, Taddei A. et al. Role of preoperative CT colonography in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:3795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flor N, Campari A, Ravelli A. et al. Vascular map combined with CT colonography for evaluating candidates for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Korean J Radiol 2015;16:821–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matsuki M, Okuda J, Kanazawa S. et al. Virtual CT colectomy by three-dimensional imaging using multidetector-row CT for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Abdom Imaging 2005;30:698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]