Abstract

During the rapid rise of the COVID-19 pandemic, a reduction of the numbers of patients presenting to emergency departments has been observed. We present an early study from a German psychiatric hospital to assess the dynamics of mental health emergency service utilization rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results show that the numbers of emergency presentations decreased, and a positive correlation between these numbers and mobility of the general public suggests an impact of extended measures of social distancing. This finding underscores the necessity of raising and sustaining awareness regarding the threat to mental health in the context of the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemics, Psychiatry, Emergency treatment

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic affects most aspects of society and represents a major psychosocial stressor whose impact on the incidence of mental disorders has already been noted [1]. It is therefore potentially worrisome that a reduction of numbers of patients seeking medical emergency care has been observed by clinicians worldwide [2, 3]. Reasons for this phenomenon are not properly understood even though some suggest that patients’ fear of in-hospital infection causes avoidance behavior.

This retrospective study aimed to quantify the dynamics of mental health emergency service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic and to assess a potential impact of the partial lockdown in Germany. It was performed at the Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim, Germany, a large psychiatric hospital serving a catchment area of ~ 300,000 people caring for nearly all psychiatric emergencies in the city of Mannheim (~ 4500 presentations/year). Patient allocation to the hospital’s emergency service is carried out by practice-based physicians, physicians from other hospitals in the city, emergency medical service providers and/or police departments. The service is also open for self-referring patients. All patients requiring evaluation and/or treatment for a mental health condition are seen by the emergency service staff.

During the pandemic, the service has been operating unrestrictedly, however, precautionary measures have been taken to minimize risk of infection transmission. All presenting patients were asked to disinfect their hands and don a face mask upon arrival in the hospital. As part of a screening assessment to identify potentially infected patients, a targeted history regarding symptoms of illness and recent contact with patients with proven SARS-CoV-2 infection was obtained and patients’ temperature was taken. If patients were unable to provide necessary information, every effort was made to obtain this from family or acquaintances.

Data of patients seeking help from hospital emergency service between 01/01/2019 and 04/21/2019 and between 01/01/2020 and 04/19/2020 were collected from clinical service records and included demographic data and final diagnosis after psychiatric evaluation. Anonymized mobility data of the general public were obtained from Teralytics, Zurich, Switzerland.

Week 12 when the pandemic risk was raised to “high” by the German regulator was defined as the week when the COVID-19 pandemic impacted public life and extended measures for social distancing, e.g., through the closure of schools and daycare institutions, were beginning to be implemented.

Weeks 1–11 (early) and 12–15 (late) were categorized into a variable “epoch” for years 2019 and 2020. Poisson regression was used to test if the rate of admissions changed as a function of year, epoch and year-by-epoch interaction (reflecting impact of the pandemic), expressed as rate ratio (RR) along with its 95% confidence interval. With Spearman’s rho, correlations between mobility and emergency service presentations were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.

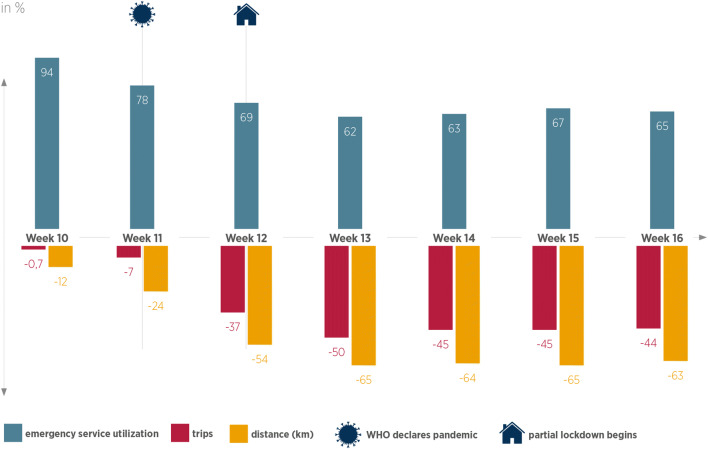

Emergency service presentation rates decreased significantly by 26.6% [RR = 0.734, p = 0.009, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.58–0.93] between early (weeks 1–11) and late (weeks 12–15) epochs in 2019 and 2020, reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Significant year-by-epoch-interactions were found for presentations due to organic mental disorders including dementia (− 51.6%, RR 0.484, p = 0.024, 95% CI 0.26–0.91) and affective disorders (− 42.3%; RR = 0.577, p = 0.016, 95% CI 0.37–0.90) but only in the latter did we find an interaction driven by a difference between the epochs before and after the pandemic’s onset. Beginning week 12, a pronounced decrease in mobility of the general public in Mannheim was observed, which predicted reduced emergency service utilization (number of trips rs 0.631, p = 0.012, kilometers traveled rs = 0.538, p = 0.038) and a reduced number of presentations due to affective disorders (number of trips rs = 0.783, p = 0.001, kilometers traveled rs = 0.787, p = 0.001; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Difference (in %) of mental health service utilization (positive Y axis) between weeks 10–15 in 2020 and weeks 10–15 in 2019, and difference (in %) of number of trips (red) and kilometers traveled (orange) in Mannheim (negative Y axis), between calendar weeks 2–11 and weeks 12–15 in 2020

This study identified a decrease of mental health emergency service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic and for the first time extends observations made in other specialties [2, 3] to psychiatry.

In the context of quarantine and social distancing, themselves risk factors for mental disorders [4], as well as their repercussions on financial and job security, mental health issues are expected to increase during the pandemic, as they did during previous societal crises. We identified a particular impact of the pandemic on the number of presentations due to affective disorders, which is concerning since bi-directional influences between depressive symptoms and social disconnectedness and isolation exist [5]. The correlation of lower service utilization rates and decreased population mobility moreover suggests an impact of extended measures of social distancing on patients’ willingness to seek help for mental health problems through in-hospital consultations. On a related note, medical workers from all around the world have been joining campaigns urging people to stay home, which may inadvertently contribute to this development.

Our observation warrants serious attention even more so because this development occurred against a backdrop of sufficient capacities for patient evaluation, admission and care with the hospital’s emergency mental health service operating in an uninterrupted and unrestricted manner during the pandemic.

Disasters such as the current pandemic in particular impact on society’s most vulnerable populations, among them patients with mental illness. Our findings underscore the need for raising and sustaining awareness regarding the threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic for mental health—for those with mental illness but potentially also for previously healthy people [6]. It is paramount for psychiatry to ensure that state-of-the-art service be delivered in these challenging times through the development and refinement of adaptive strategies in patient care within the broader context of the healthcare system through engaging with patients, clinicians and health policies [7]. These include, for example, the implementation and extended use of alternative strategies of mental healthcare delivery like telehealth [8, 9] to ensure accessibility to psychiatric care, the development of online tools to support individuals with risk factors and mitigate the effects of social isolation [10], and the creation of encouraging, safe and trusting environments for walk-ins. Efforts like these will be essential to avoid serious healthcare and economic consequences resulting from undiagnosed or untreated mental disorders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Matthias Gondan, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, for statistical advice.

Funding

CH receives a grant for postdoctoral lecture qualification within the Olympia Morata Program of Heidelberg University.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bersano A, Pantoni L. On being a neurologist in Italy at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. Neurology. 2020;94(21):905–906. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, Dixon S, Rade JJ, Tannenbaum M, Chambers J, Huang PP, Henry TD. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;S0735–1097(20):34913–34915. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Madsen KR, Koushede V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e62–70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman KR, Petkova E, Bhui KS, Schulze TG. A global needs assessment in times of a global crisis: world psychiatry response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(3):e48. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druss BG. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu N, Pan S, Sun J, Wang Z, Mao H. Mental health treatment online during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosc. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myin-Germeys I. Digital technology in psychiatry: towards the implementation of a true person-centered care in psychiatry. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;270(4):401–402. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meinert E, Milne-Ives M, Surodina S, Lam C. Agile requirements engineering and software planning for a digital health platform to engage the effects of isolation caused by social distancing: case study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19297. doi: 10.2196/19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]