Abstract

Background

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is common and disabling in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Predictors of EDS are unclear, and data on biological correlates of EDS in PD are limited. We investigated clinical, imaging and biological variables associated with longitudinal changes in sleepiness in early PD.

Methods

The Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative is a prospective cohort study evaluating progression markers in participants with PD who are unmedicated at baseline (n=423) and healthy controls (HC; n=196). EDS was measured with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Clinical, biological and imaging variables were assessed for associations with EDS for up to 3 years. A machine learning approach (random survival forests) was used to investigate baseline predictors of incident EDS.

Results

ESS increased in PD from baseline to year 3 (mean±SD 5.8±3.5 to 7.55±4.6, p<0.0001), with no change in HC. Longitudinally, EDS in PD was associated with non-tremor dominant phenotype, autonomic dysfunction, depression, anxiety and probable behaviour disorder, but not cognitive dysfunction or motor severity. Dopaminergic therapy was associated with EDS at years 2 and 3, as dose increased. EDS was also associated with presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction, whereas biofluid markers at year 1 showed no significant associations with EDS. A predictive index for EDS was generated, which included seven baseline characteristics, including non-motor symptoms and cerebrospinal fluid phosphorylated-tau/total-tau ratio.

Conclusions

In early PD, EDS increases significantly over time and is associated with several clinical variables. The influence of dopaminergic therapy on EDS is dose dependent. Further longitudinal analyses will better characterise associations with imaging and biomarkers.

INTRODUCTION

Although Parkinson’s disease (PD) is defined by its motor manifestations, non-motor symptoms (NMS) are also common and often more disabling than motor symptoms.1 Disorders of sleep and wakefulness are among the most common NMS in PD. Specifically, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) affects 16% to 55% of patients with PD, increasing with disease duration and severity.2–4 This symptom negatively impacts safety and quality of life4,5 and has been associated with male sex, older age, non-tremor dominant (TD) phenotype, autonomic dysfunction, cognitive impairment and psychosis.6–8 The aetiology of EDS in PD is multi-factorial, related to neurodegeneration within the ascending arousal systems, dopaminergic medication effects, nocturnal sleep dysfunction and as yet unknown factors.6,9,10 It is well established that EDS is more common in moderate to advanced PD compared with healthy controls (HC).3,4

We previously reported baseline characteristics related to EDS in a cohort of de novo unmedicated patients with PD and matched HC recruited into the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI).11 In this cohort, there was no difference in EDS, as measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), between de novo PD and controls.2 Associations with EDS included depression, autonomic dysfunction, anxiety and probable rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder (pRBD). Interestingly, there was no association between EDS and cognition or motor severity at baseline. The only biological variable associated with EDS was marginally lower levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) beta-amyloid 1–42 (A-beta).

Although multiple cross-sectional studies address EDS in PD, few investigate its longitudinal incidence and prevalence.6,7,12,13 One study examined longitudinal changes in EDS in 153 de novo patients with PD compared with HC, finding that participants with PD had more EDS over time.13 Another study found more frequent and longer napping among established, recent and even prediagnostic PD cases compared with controls.14 In all but one7 longitudinal study, EDS prevalence increased over time.6,12,13No prior studies report the influence of imaging and CSF biological markers on longitudinal incidence and prevalence of EDS, which is of paramount significance given the putative association between EDS and the extent of neurodegeneration in PD.10 Additionally, questions remain regarding the influence of medications, motor and NMS and degree of nigrostriatal dopamine depletion on EDS in PD. In light of these knowledge gaps, we aimed to better characterise the epidemiological, clinical and biological factors associated with EDS in PD by investigating its incidence and longitudinal prevalence among participants with PD and HC in the PPMI cohort. Further, we assessed the baseline clinical and biological predictors of incident development of EDS in PD.

METHODS

Participants

All participants were enrolled in PPMI, an observational, international, multicentre investigation of clinical, biological and neuroimaging markers of PD progression, previously described in detail.11 In brief, participants include 423 patients with PD who were drug naive and within 2 years of diagnosis at enrolment and 196 matched HC. Enrolment required at least two of three cardinal signs of PD (bradykinesia, rigidity or rest tremor) as well as dopamine transporter deficit on 123I ioflupane imaging (DaTscan). Each PPMI site received approval from an ethical standards committee on human experimentation, and participants gave written informed consent.

Data were accessed from the PPMI database (www.ppmi-info.org) on 1 July 2015.

Assessments

Participants were evaluated at baseline and yearly with the ESS,15 a validated measure of EDS in which participants rate their likelihood of falling asleep in eight situations. Items are ranked 0–3, with higher scores indicating more sleepiness and maximum score of 24. This scale has high test–retest correlation, high internal consistency and unidimensionality (ie, all items of the scale measure one thing: sleepiness).16 The ESS also correlates with objective measures of sleepiness in PD,17,18 is sensitive to change due to an intervention19 and is recommended by the Movement Disorders Society Sleep Scale Task Force to assess EDS in PD.19 Participants were categorised as having EDS if ESS was ≥1020 and having severe EDS if ESS was ≥17.15 Subjects were also assessed with the Movement Disorders Society—Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS),21 which was also used to classify participants as TD or non-TD at each time point.22 The Postural Instability/Gait Disorder (PIGD) score was also calculated.22 Additional assessments included the Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage,23 the Modified Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale (S&E),24 the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),25 the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale,26 the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease—Autonomic (SCOPA-AUT),27 the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) state and trait subscores,28 the Questionnaire for Impulsive–Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale29 and the REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder Screening Questionnaire (RBDSQ).30 Participants were classified as screening positive for pRBD if they scored >5 on the RBDSQ or if they answered affirmatively for at least one of the four subitems of item 6 of RBDSQ.31 Data on obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) were obtained by patient report of prior diagnosis. Data on sedative use were ascertained from study medication logs based on the Federal Drug Administration drug classification. Dopaminergic therapy usage was calculated as levodopa equivalent dose (LED), as previously described.32

Participants were also evaluated with DaTscan at screening and years 1 and 2 to assess the degree of presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction, analysed as per the imaging technical operations manual (www.ppmi-info.org).11 Biological assessments included serum urate, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) epsilon-4 genotype and CSF analysis of A-beta 1–42, total tau (T-tau), tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (P-tau181) and unphosphorylated alpha-synuclein. Details of sample collection, processing and biomarker analyses were previously reported.33

Statistical methods

Longitudinal analysis of EDS in PD and HC

t-Test or χ2 test was used to compare baseline demographics and clinical characteristics between PD subjects and controls and to compare demographics, clinical characteristics and DaTscan measures at each time point between patients with PD with and without EDS. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare CSF biologics between patients with PD with and without EDS.

Linear or logistic mixed models were used to test for changes in sleep characteristics over time separately in patients with PD and controls and to test for differences in sleep characteristics between groups over time. In these latter models, an interaction between time and group was tested before testing for overall group difference. A significant test of interaction indicates a difference in rates of change over time. If the test of interaction was not significant at 0.10 level, the interaction term was removed from the model and a test for overall group difference was reported. Models without the interaction term assume similar rates of change in the groups; therefore, a test for overall group difference was only reported when the interaction was not significant. Significance was considered achieved if p<0.05.

Predictive modelling of incident EDS

The goal was to predict incident EDS using variables measured at study entry. The outcome of years to EDS from baseline was censored for 73% of the sample. Because the analysis was exploratory and involved 33 baseline variables (online supplementary table 1), the machine learning method of random survival forests (RSF) was used.34 This is a useful method for exploratory analysis in neurodegenerative diseases.35

RSF is a variant of random forests for right-censored data and is based on recursive regression trees grown on bootstrap samples of the data. Here, 2000 trees were grown for each group of predictors, with <1% missing data for predictors (none missing for time to EDS), which was handled using dynamic iterated imputation.34 Ranking of variable merit (strength of prediction) was based on variable importance (comparative prediction error under randomisation) and minimal depth (how deep in a tree a variable tends to appear). To provide reliable ranking, the 2000-tree RSF was run five times, yielding 10 rankings (two per measure). The rankings were summarised by the median of the normalised ranks (each rank divided by 33) and by a p value that indicates the probability of a variable’s rank position under random ordering. The ranking score of −log(p value) was used to order the variables and determine subgroups for additional analysis. Two models were planned prior to analysis, and five models were unplanned. The planned models included a reference model with no predictors (reference 0) and the model with all 33 predictors (RSF-33). One unplanned model was a Cox model with seven predictors included to clarify the nature of predictor effects. All models were developed on the full data set, and the concordance index, C, was used to index in-sample prediction accuracy. C indexes the extent to which the predicted survival for a pair of participants correctly orders them in terms of their actual time to EDS. A recent survey of oncology and cardiovascular research found mean C=0.78 with a lower quartile of 0.69.36 Therefore, C<0.69 represents a ‘small’ effect. Because C is not a strictly proper scoring rule, the time-dependent Brier Score (BS) was used to compare the training predicted probabilities and the test observed EDS status in the crossvalidation. A weighted form of the BS was used to account for censoring bias. A pseudo-R2 was computed for each model, indicating the proportional reduction relative to the model with no predictors. RSF is further detailed in the supplementary material.

RESULTS

At the time of download from the PPMI database (www.ppmi-info.org) on 1 July 2015, data were available for 397 participants with PD at year 1, 378 at year 2 and 204 at year 3. For HC, data were available for 185 participants at year 1, 172 at year 2 and 133 at year 3. Demographics of HC and participants with PD (total and ±EDS) were previously reported.2 Specifically, there were no significant differences between HC and participants with PD in terms of age, gender, education, ethnicity, race or ApoE epsilon−4 genotype.2 Further, when comparing participants with PD with (n=66) and without (n=357) EDS at baseline, there were no significant differences in age, gender, education, ethnicity, race, family history of PD, duration of disease, age of diagnosis of PD, side most affected by motor symptoms or ApoE epsilon−4 genotype.2

Longitudinal change in EDS in PD and HC

Participants with PD had a significant increase in mean ESS score from baseline to year 3 (p<0.0001) (table 1). This increase in ESS exceeds a clinically meaningful change (≥20%).37 Further, there was a significant longitudinal increase in the proportion of participants with PD who were classified as having EDS (p=0.0005), whereas HC demonstrated no increase in ESS over time and no significant longitudinal increase in the proportion classified as having EDS. In addition, rates of change in EDS over time were significantly different between PD and HC (group×visit interaction, p<0.0001). The proportion of participants with PD with severe EDS (ESS≥17) also significantly increased over time. There were too few HC with severe EDS to perform longitudinal analysis on this group.

Table 1.

Sleep disorders over time in PD and HC

| Patients with PD | HC | p Values | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline (n=423) | Year 1 (n=397) | Year 2 (n=378) | Year 3 (n=204) | p Value (change over time) | Baseline (n=196) | Year 1 (n=185) | Year 2 (n=172) | Year 3 (n=133) | p Value (change over time) | Group×visit interaction | PD vs HC |

| ESS | <0.0001 | 0.801 | <0.0001 | NA* | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.5) | 6.1 (4.0) | 6.8 (4.1) | 7.6 (4.6) | 5.6 (3.4) | 5.4 (3.2) | 5.5 (3.5) | 5.7 (3.7) | ||||

| (Min, max) | (0, 20) | (0, 21) | (0, 23) | (0, 24) | (0, 19) | (0, 16) | (0, 17) | (0, 18) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| EDS | 0.0005 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| Negative (<10) | 357 (84.4%) | 329 (83.3%) | 284 (77.4%) | 143 (73.0%) | 171 (87.7%) | 165 (89.2%) | 149 (86.6%) | 111 (83.5%) | ||||

| Positive (≥10) | 66 (15.6%) | 66 (16.7%) | 83 (22.6%) | 53 (27.0%) | 24 (12.3%) | 20 (10.8%) | 23 (13.4%) | 22 (16.5%) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Severe EDS | 0.013 | NA† | NA† | NA† | ||||||||

| Negative (<17) | 421 (99.5%) | 388 (98.2%) | 359 (97.8%) | 188 (95.9%) | 194 (99.5%) | 185 (100.0%) | 171 (99.4%) | 130 (97.7%) | ||||

| Positive (≥17) | 2 (0.5%) | 7 (1.8%) | 8 (2.2%) | 8 (4.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.3%) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| RBD score | <0.0001 | 0.28 | <0.0001 | NA* | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.12 (2.7) | 4.11 (2.8) | 4.54 (3.0) | 4.93 (2.9) | 2.83 (2.3) | 2.81 (2.3) | 2.61 (2.3) | 2.68 (2.2) | ||||

| (Min, max) | (0, 12) | (0, 13) | (0, 13) | (0, 12) | (0, 11) | (0, 11) | (0, 11) | (0, 11) | ||||

| Missing | 3 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| RBD | 0.0001 | 0.52 | 0.01 | NA* | ||||||||

| Negative (≤5) | 312 (74.3%) | 292 (74.3%) | 248 (67.4%) | 118 (60.2%) | 171 (87.2%) | 164 (88.7%) | 154 (90.1%) | 120 (90.2%) | ||||

| Positive (>5) | 108 (25.7%) | 101 (25.7%) | 120 (32.6%) | 78 (39.8%) | 25 (12.8%) | 21 (11.3%) | 17 (9.9%) | 13 (9.8%) | ||||

| Missing | 3 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| RBD question 6 | 0.0005 | 0.006 | <0.0001 | NA† | ||||||||

| Negative (no parts >0) | 227 (53.8%) | 235 (59.6%) | 188 (51.1%) | 85 (43.4%) | 132 (67.4%) | 130 (70.3%) | 136 (79.1%) | 99 (74.4%) | ||||

| Positive (1+ parts >0) | 195 (46.2%) | 159 (40.4%) | 180 (48.9%) | 111 (56.6%) | 64 (32.6%) | 55 (29.7%) | 36 (20.9%) | 34 (25.6%) | ||||

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| OSA | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.54 | 0.072 | ||||||||

| Negative | 399 (94.3%) | 372 (93.7%) | 355 (93.9%) | 189 (92.7%) | 190 (96.9%) | 178 (96.2%) | 166 (96.5%) | 127 (95.5%) | ||||

| Positive | 24 (5.7%) | 25 (6.3%) | 23 (6.1%) | 15 (7.4%) | 6 (3.1%) | 7 (3.8%) | 6 (3.5%) | 6 (4.5%) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; HC, healthy controls; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; PD, Parkinson’s disease; RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder.

PD versus HC comparison is not applicable if test of interaction was significant.

There were not enough positive results in the HC group to run analysis.

Regarding other sleep disorders, the proportion of participants with PD with pRBD increased over time, whether this was assessed by the total RBDSQ (score >5) or question 6 alone (table 1). The proportion of HC screening positive for pRBD by question 6 of RBDSQ decreased over time, and the rates of change in pRBD were significantly different between PD and HC. There was no significant longitudinal change in the diagnosis of OSA among participants with PD or HC, although there was a trend toward higher proportion of OSA diagnosis in PD compared with HC. To better characterise the influence of OSA diagnosis on EDS among participants with PD, we performed subgroup analysis based on OSA diagnosis. There was no difference in ESS score or EDS in those with and without OSA at baseline and year 3. However, at years 1 and 2, ESS was higher, and there were more participants with PD with EDS among those with OSA (online supplementary table 2). Treatment status of OSA is not known, limiting interpretation.

The characteristics of participants with PD with and without EDS in the 3 years following enrolment are shown in table 2. At each time point, subjects with EDS had worse total, part I (neuropsychiatric and NMS assessment) and part II (patient-completed experiences of daily living) MDS-UPDRS, with no significant difference in part III (motor) MDS-UPDRS or H&Y stage, although the number of subjects with H&Y >2 was small. The S&E score was lower (more impaired) in participants with PD with EDS at years 2 and 3 only. Participants without EDS were more likely to be classified as TD than participants with EDS, and those with EDS had worse (higher) PIGD scores on the MDS-UPDRS. There was no significant difference between groups in terms of most affected side. In regard to association of EDS with other NMS, there was no significant difference in cognition (MoCA) between groups at any time point. Similar to baseline findings in this cohort,2 EDS was associated with depression, autonomic dysfunction, anxiety and pRBD at each time point. In contrast to baseline, subjective impulsivity was higher among those with EDS at years 1 and 2, but not year 3.

Table 2.

PD motor and non-motor characteristics and medication use over time by EDS status

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PD EDS+(n=66) | PD EDS−(n=329) | p Value | PD EDS+(n=83) | PD EDS−(n=284) | p Value | PD EDS+(n=53) | PD EDS−(n=143) | p Value |

| MDS-UPDRS mean (SD) | |||||||||

| MDS-UDPRS total | 45.2 (18.1) | 38.5 (15.7) | 0.006 | 51.9 (17.8) | 41.3 (16.2) | <0.0001 | 59.1 (23.9) | 45.5 (16.2) | 0.0004 |

| MDS-UDPRS part I | 9.0 (5.4) | 6.3 (4.3) | <0.0001 | 10.5 (5.5) | 6.9 (4.6) | <0.0001 | 12.1 (6.2) | 7.3 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| MDS-UDPRS part II | 9.6 (5.8) | 7.1 (4.8) | 0.0004 | 10.8 (6.0) | 7.3 (4.8) | <0.0001 | 13.3 (7.1) | 7.9 (4.7) | <0.0001 |

| MDS-UDPRS part III | 26.6 (10.9) | 25.2 (11.0) | 0.41 | 29.3 (12.3) | 27.2 (11.0) | 0.22 | 34.2 (15.9) | 30.2 (11.4) | 0.12 |

| Missing | 11 | 63 | 29 | 71 | 21 | 44 | |||

| Hoehn & Yahr | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.46 | ||||||

| Stage 0 | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Stage 1 | 18 (32.7%) | 75 (28.3%) | 9 (16.7%) | 56 (26.3%) | 5 (15.6%) | 18 (18.2%) | |||

| Stage 2 | 33 (60.0%) | 180 (67.9%) | 42 (77.8%) | 145 (68.1%) | 22 (68.8%) | 73 (73.7%) | |||

| Stages 3–5 | 4 (7.3%) | 9 (3.4%) | 3 (5.6%) | 10 (4.7%) | 5 (15.6%) | 8 (8.1%) | |||

| Missing | 11 | 64 | 29 | 71 | 21 | 44 | |||

| S&E | 0.92 | 0.017 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 90.4 (6.7) | 90.5 (6.7) | 86.8 (9.6) | 89.2 (7.5) | 82.9 (9.7) | 88.1 (7.9) | |||

| (Min, max) | (70, 100) | (70, 100) | (60, 100) | (60, 100) | (50, 100) | (60, 100) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| TD/non-TD classification | 0.004 | 0.12 | 0.081 | ||||||

| TD | 28 (50.9%) | 189 (71.0%) | 31 (57.4%) | 146 (68.5%) | 18 (56.2%) | 72 (72.7%) | |||

| Non-TD | 27 (49.1%) | 77 (29.0%) | 23 (42.6%) | 67 (31.5%) | 14 (43.8%) | 27 (27.3%) | |||

| Missing | 11 | 63 | 29 | 71 | 21 | 44 | |||

| Tremor score | 0.16 | 0.68 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.53 (0.4) | 0.61 (0.4) | 0.64 (0.5) | 0.61 (0.4) | 0.65 (0.3) | 0.74 (0.5) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 2.0) | (0, 1.6) | (0, 2.2) | (0, 2.5) | (0, 1.2) | (0, 2.3) | |||

| Missing | 11 | 63 | 29 | 71 | 21 | 44 | |||

| PIGD score | 0.014 | 0.065 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.40 (0.3) | 0.30 (0.3) | 0.44 (0.3) | 0.33 (0.4) | 0.68 (0.7) | 0.39 (0.4) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 1.6) | (0, 1.8) | (0, 1.6) | (0, 3.0) | (0, 3.0) | (0, 2.0) | |||

| Missing | 11 | 63 | 29 | 71 | 21 | 44 | |||

| Side most affected | 0.24 | 0.057 | 0.090 | ||||||

| Left | 29 (43.9%) | 136 (41.3%) | 34 (41.0%) | 121 (42.6%) | 20 (37.74%) | 54 (37.76%) | |||

| Right | 34 (51.52%) | 188 (57.14%) | 44 (53.0%) | 159 (56.0%) | 30 (56.6%) | 88 (61.5%) | |||

| Symmetric | 3 (4.6%) | 5 (1.5%) | 5 (6.0%) | 4 (1.4%) | 3 (5.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| MoCA | 0.12 | 0.080 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.8 (3.2) | 26.4 (2.7) | 25.7 (4.0) | 26.4 (2.9) | 25.6 (3.8) | 26.2 (3.0) | |||

| (Min, max) | (15, 30) | (19, 30) | (9, 30) | (16, 30) | (13, 30) | (14, 30) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| GDS | 0.035 | 0.0006 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.26 (2.8) | 2.43 (2.9) | 3.55 (3.2) | 2.34 (2.7) | 3.91 (3.4) | 2.14 (2.4) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 15) | (0, 14) | (0, 15) | (0, 15) | (0, 14) | (0, 11) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SCOPA-AUT | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.73 (7.9) | 10.15 (5.8) | 15.72 (8.3) | 10.31 (5.5) | 16.30 (7.0) | 11.51 (6.4) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 45) | (0, 39) | (0, 42) | (0, 32) | (2, 31) | (0, 30) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| STAI—state subscore | 0.003 | 0.0001 | 0.015 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 35.76 (9.6) | 31.79 (10.0) | 36.06 (10.7) | 31.28 (9.7) | 34.74 (10.3) | 31.06 (8.9) | |||

| (Min, max) | (21, 60) | (20, 77) | (20, 70) | (20, 76) | (20, 60) | (20, 67) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| STAI—trait subscore | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.24 (10.2) | 31.78 (9.3) | 36.42 (9.4) | 31.37 (9.3) | 37.15 (10.5) | 31.55 (9.1) | |||

| (Min, max) | (22, 60) | (20, 73) | (21, 59) | (20, 66) | (21, 56) | (20, 63) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| QuIP | 0.002 | 0.040 | 0.27 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.33 (0.7) | 0.13 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.8) | 0.26 (0.6) | 0.43 (0.8) | 0.31 (0.7) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 3) | (0, 3) | (0, 4) | (0, 5) | (0, 4) | (0, 4) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| RBD | 0.023 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||||||

| Negative (≤5) | 41 (63.1%) | 251 (78.5%) | 38 (45.8%) | 209 (73.6%) | 21 (39.6%) | 97 (67.8%) | |||

| Positive (>5) | 24 (36.9%) | 77 (23.5%) | 45 (54.2%) | 75 (26.4%) | 32 (60.4%) | 46 (32.2%) | |||

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| RBD question 6 | 0.0001 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Negative (all parts=0) | 25 (38.5%) | 210 (63.8%) | 29 (34.9%) | 158 (55.6%) | 10 (18.9%) | 75 (52.5%) | |||

| Positive (one or more parts >0) | 40 (61.5%) | 119 (36.2%) | 54 (65.1%) | 126 (44.4%) | 43 (81.1%) | 68 (47.6%) | |||

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Utilisation of sedatives | 0.96 | 0.54 | 0.017 | ||||||

| No sedatives used | 54 (81.8%) | 270 (82.1%) | 65 (78.3%) | 231 (81.3%) | 33 (62.3%) | 113 (79.0%) | |||

| Sedatives used | 12 (18.2%) | 59 (17.9%) | 18 (21.7%) | 53 (18.7%) | 20 (37.7%) | 30 (21.0%) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Treated at Year 1 | Treated at Year 2 | Treated at Year 3 | |||||||

| Variable | PD EDS+(n=43) | PD EDS−(n=184) | p Value | PD EDS+(n=69) | PD EDS−(n=230) | p Value | PD EDS+(n=50) | PD EDS−(n=120) | p Value |

| Total LED | 0.23 | 0.0006 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 230.4 (139.5) | 277.8 (184.3) | 410.3 (246.6) | 291.9 (188.1) | 493.2 (269.2) | 315.7 (186.7) | |||

| (Min, max) | (50, 600) | (30, 850) | (100, 1050) | (50, 940) | (100, 1000) | (75, 920) | |||

| Missing | 18 | 73 | 20 | 91 | 15 | 42 | |||

| LED subtotal—dopamine agonists | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.63 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 84.4 (90.9) | 58.8 (91.9) | 94.9 (143.6) | 80.5 (111.3) | 83.1 (119.4) | 95.1 (124.9) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 300) | (0, 450) | (0, 825) | (0, 450) | (0, 450) | (0, 480) | |||

| Missing | 18 | 73 | 20 | 91 | 15 | 42 | |||

| LED subtotal—non-dopamine agonists | 0.080 | 0.004 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 146.0 (166.4) | 218.9 (190.7) | 315.4 (272.5) | 211.4 (193.2) | 410.1 (306.7) | 220.5 (186.8) | |||

| (Min, max) | (0, 600) | (0, 800) | (0. 1050) | (0, 800) | (0, 1000) | (0, 750) | |||

| Missing | 18 | 73 | 20 | 91 | 15 | 42 | |||

| Use of classes of PD medications* | |||||||||

| Levodopa±entacapone | 13 (30.2%) | 70 (38.0%) | 0.34 | 32 (46.4%) | 100 (43.5%) | 0.67 | 36 (72.0%) | 51 (42.5%) | 0.0005 |

| MAO-B inhibitors | 18 (41.9%) | 77 (41.9%) | 0.999 | 31 (44.9%) | 100 (43.5%) | 0.83 | 17 (34.0%) | 55 (45.8%) | 0.16 |

| Dopamine agonists | 17 (39.5%) | 62 (33.7%) | 0.47 | 32 (46.4%) | 92 (40.0%) | 0.35 | 22 (44.0%) | 49 (40.8%) | 0.70 |

| Amantadine | 2 (4.7%) | 21 (11.4%) | 0.19 | 8 (11.6%) | 30 (13.0%) | 0.75 | 7 (14.0%) | 22 (18.3%) | 0.49 |

| Anticholinergics | 2 (4.7%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0.36 | 4 (5.8%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.030 | 4 (8.0%) | 6 (5.0%) | 0.45 |

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; LED, levodopa equivalent dose; MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorders Society—Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale;MAO-B; Monoamine oxidase-B,MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PIGD, Postural Instability/Gait Disorder; QuIP, Questionnaire for Impulsive–Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder; SCOPA-AUT, Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease—Autonomic; S&E, Modified Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale; STAI, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; TD, tremor dominant.

There was no significant difference in sedative use at years 1 or 2, but at year 3, more participants with PD with EDS used sedatives than those without EDS (table 2). Regarding dopaminergic therapy, there was no difference in total LED at year 1. At years 2 and 3, however, participants with EDS had a significantly higher total LED than those without EDS. There was no significant difference between groups for the dopamine agonist LED subtotal at any time point, although the dopamine agonist LED in the group was relatively low (table 2).

Biological correlates of EDS

Participants with PD with EDS demonstrated significantly more presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction, as measured by DaTscan, in the contralateral and ipsilateral caudate and contralateral putamen compared with patients with PD without EDS at years 1 and 2 (table 3). DaTscan is not obtained at year 3.

Table 3.

Presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction over time as measured by DaTscan

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PD EDS+(n=66) | PD EDS−(n=329) | p Value | PD EDS+(n=83) | PD EDS−(n=284) | p Value |

| Contralateral caudate | 0.022 | 0.044 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.51 (0.49) | 1.66 (0.49) | 1.43 (0.50) | 1.58 (0.52) | ||

| (Min, max) | (0.58, 2.57) | (0.26, 3.58) | (0.49, 2.92) | (0.53, 3.52) | ||

| Missing | 4 | 37 | 22 | 101 | ||

| Ipsilateral caudate | 0.002 | 0.028 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.73 (0.62) | 1.97 (0.53) | 1.69 (0.61) | 1.88 (0.56) | ||

| (Min, max) | (0.60, 3.26) | (0.31, 3.81) | (0.25, 2.92) | (0.49, 3.72) | ||

| Missing | 4 | 37 | 22 | 101 | ||

| Contralateral putamen | 0.008 | 0.012 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.53 (0.19) | 0.62 (0.23) | 0.50 (0.21) | 0.58 (0.21) | ||

| (Min, max) | (0.20, 1.12) | (0.07, 1.81) | (0.07, 1.15) | (0.15, 1.47) | ||

| Missing | 4 | 37 | 22 | 101 | ||

| Ipsilateral putamen | 0.012 | 0.092 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.69 (0.29) | 0.80 (0.31) | 0.67 (0.28) | 0.75 (0.33) | ||

| (Min, max) | (0.08, 1.56) | (0.03, 2.12) | (0.07, 1.55) | (0.21, 2.21) | ||

| Missing | 4 | 37 | 22 | 101 | ||

Note: Year 3 DaTscan data are not yet available.

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; PD, Parkinson’s disease.

At baseline, we previously reported marginally lower levels of CSF A-beta in participants with PD, with compared with without EDS.2 This was no longer the case at year 1 (table 4). There were also no significant differences between groups in CSF t-tau, p-tau, t-tau/A-beta, p-tau/A-beta, p-tau/t-tau, alpha-synuclein, serum urate or ApoE epsilon−4 genotype. Biological data for years 2 and 3 were not yet available when data were accessed.

Table 4.

Biologics at year 1 in participants with PD by EDS status

| Year 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PD EDS+(n=66) | PD EDS−(n=329) | p Value* |

| A-beta | 0.65 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 377.2 (125.8) | 376.4 (98.3) | |

| (Min, max) | (184.4, 732.5) | (144.1, 669.1) | |

| Missing | 33 | 186 | |

| t-tau | 0.85 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 (12.9) | 43.3 (18.2) | |

| (Min, max) | (22.9, 75.9) | (16.6, 128.8) | |

| Missing | 34 | 186 | |

| p-tau | 0.79 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 19.3 (14.1) | 18.3 (11.1) | |

| (Min, max) | (5.4, 57.9) | (5.4, 61.8) | |

| Missing | 33 | 187 | |

| t-tau/A-beta | 0.92 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.07) | |

| (Min, max) | (0.08, 0.26) | (0.06, 0.51) | |

| Missing | 34 | 186 | |

| p-tau/A-beta | 0.85 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.04) | |

| (Min, max) | (0.02,0.26) | (0.01, 0.28) | |

| Missing | 33 | 187 | |

| p-tau/t-tau | 0.83 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.47 (0.29) | 0.47 (0.35) | |

| (Min, max) | (0.16, 1.17) | (0.07, 2.48) | |

| Missing | 34 | 187 | |

| Alpha-synuclein | 0.33 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1760.0 (748.0) | 1897.6 (817.3) | |

| (Min, max) | (805.1, 4396.4) | (352.4, 5157.1) | |

| Missing | 33 | 186 | |

| Urate | 0.21 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 322.6 (79.5) | 309.3 (75.6) | |

| (Min, max) | (184.0, 529.0) | (161.0, 500.0) | |

| Missing | 5 | 30 | |

| Apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 genotype | 0.07 | ||

| 0 | 36 (62.07%) | 229 (76.59%) | |

| 1 | 20 (34.48%) | 63 (21.07%) | |

| 2 | 2 (3.45%) | 7 (2.34%) | |

| Missing | 8 | 30 | |

p Values are from Mann-Whitney U tests.

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; PD, Parkinson’s disease.

Predictors of incident EDS

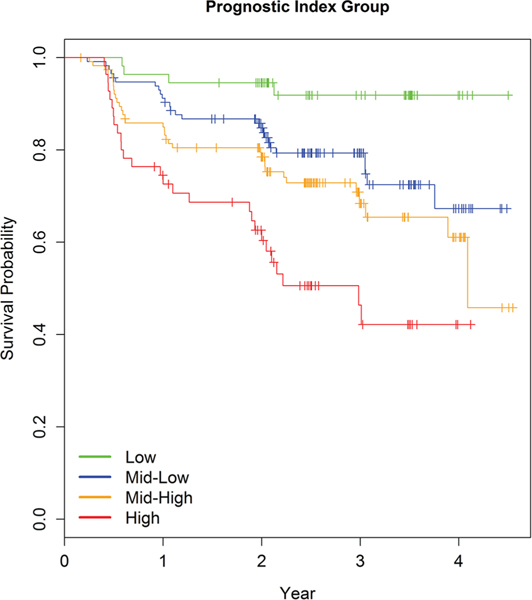

To determine baseline clinical and biological variables that predict incident development of EDS, we evaluated the 353 participants with PD in this cohort who did not have EDS at baseline. Ninety-four (27%) subsequently developed EDS. Results based on in-sample concordance and crossvalidated prediction accuracy showed that the best model had seven variables (SCOPA-AUT, STAI-Trait, MDS-UPDRS Part I, STAI-State, MDS-UPDRS total score, MDS-UPDRS Part II and p-tau/t-tau) and weakly predicted time to EDS (C=0.65, pseudo R2=0.03) (online supplementary table 3). Prediction using these seven variables was similar to using all 33 variables and only marginally better than the model including no predictors. Ancillary analysis using Cox models suggested no important interactions or non-linear effects. HRs indicated that higher relative risk of EDS was associated with higher scores on the seven predictors. The strongest effect was for p-tau/t-tau, which had an estimated HR of 2, but a wide CI (95% CI 0.9 to 4.41) (online supplementary table 4). A prognostic index (PI) for risk of EDS was computed based on the seven-predictor Cox model estimates, and four risk groups of unequal size were formed. Survival curves varied by PI risk group, with higher PI scores indicating greater relative risk of incident development of EDS (figure 1).

Figure 1.

EDS survival curves by risk group defined by quartile cutoffs of the linear combination of predictors. EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness.

DISCUSSION

This international, multicentre study is the largest reported longitudinal investigation of the incidence of EDS and its associated clinical, DaTscan and biological characteristics in patients with de novo, untreated PD at baseline. Further, this is the only study to our knowledge to evaluate the association between CSF biomarkers and EDS in patients with PD and to investigate how these clinical and biological variables might predict incident development of EDS in this patient population. At baseline, no difference in the prevalence of EDS in untreated patients with PD and HC was present.2 In contrast, EDS increased longitudinally in PD but remained unchanged among HC. This is consistent with other longitudinal studies evaluating EDS in PD6,7,12,13and raises several interesting considerations in regard to EDS pathophysiology in PD.

Our findings, as well as those of others,38 suggest that EDS may be related to more significant neurodegeneration within the ascending arousal system of the brainstem, implicating involvement of non-dopaminergic mechanisms. The identified characteristics associated with EDS in this study lend support to this idea. Specifically, similar to findings in this cohort at baseline,2 EDS was not associated longitudinally with an increase in motor severity as measured by MDS-UPDRS Part III but was associated with higher PIGD score. This PIGD (or non-TD) phenotype was previously demonstrated to predict more rapidly progressive disability in PD39 and has been associated with cholinergic dysfunction within the brainstem, specifically involving the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN).40 Further, clinical NMS associated with EDS over time in this cohort include autonomic dysfunction, depression, anxiety and pRBD, all of which can be related to greater spread of neurodegeneration within the brainstem in areas responsible for controlling alertness, autonomic function, mood and REM atonia. For example, Lewy pathology and neuronal loss have been identified in the locus coeruleus (norepinephrine), raphe nuclei (serotonin), dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and PPN (both predominantly cholinergic) and the reticular formation.41,42 Disruption of these monoaminergic systems could explain the association between EDS, mood disturbance, autonomic dysfunction, dream enactment and PIGD phenotype in PD. These findings are also in line with recently proposed NMS phenotypes, with the ‘PARK sleep’ phenotype being associated with more brainstem involvement and including symptoms of EDS, RBD and autonomic disturbances.43,44

Similar to baseline findings in this cohort, EDS was not associated with cognitive dysfunction longitudinally. This could be explained by the minimal change in MoCA scores over the 3 years and to the early disease stage. We will continue to follow this cohort to determine if baseline EDS is associated with cognitive decline over time, as has been reported in more advanced cohorts.45

Interestingly, despite the lack of association of EDS with motor symptom severity, participants with EDS had more presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction on DaTscan. The significantly reduced binding in the bilateral caudate nuclei fits in this context because reduced dopamine transporter binding is an independent predictor of NMS in PD46 and NMS are more likely to be associated with reduced dopamine transporter binding in the caudate, whereas motor severity is more associated with reduced binding in the putamen.46,47 Similar to our findings, a smaller sample of 12 patients with PD demonstrated significant correlation between ESS and reduced dopamine transporter binding, particularly within the caudate.48 Because of the design of PPMI, this association can be followed longitudinally to determine whether the association of EDS with reduced contralateral putaminal binding will portend more severe motor disability over time.

Medications used to treat PD, particularly dopamine agonists, can contribute to EDS.7,12 In this cohort, the influence of dopaminergic medications on EDS in PD is highlighted by absence of differences compared with HC at baseline, when the PD group were unmedicated. The differences between groups emerged as participants with PD started medications. Compared with those without EDS, participants with EDS had significantly higher LED in years 2 and 3. The unexpected lack of association between EDS and dopamine agonist LED can likely be explained by the low dose of agonists used in the entire cohort.

One unique aspect of this cohort is the availability of CSF biomarkers. To date, these results are only available at baseline and year 1. Similar to baseline findings, there was no association between EDS and alpha-synuclein or tau (although tau did contribute to a multivariable PI predictive of EDS, as discussed below). Further, the marginal association of EDS with reduced A-beta at baseline was no longer evident at 1 year. We will continue to follow over time to determine any additional biomarker associations. Specific to the relationship with EDS, the analyses could be expanded in the future to include measurements of orexin, which is deficient in narcolepsy and has been demonstrated to correlate with objective measures of sleepiness in PD.49

Another novel feature of this study is the use of RSF analysis to predict incident development of EDS in participants PD without EDS at baseline. The best prediction model with seven variables weakly predicted time to EDS. CSF p-tau/t-tau emerged as the strongest predictor of incident EDS, with a HR near 2, although the CI was wide and none of the clinical or biological variables were robust predictors of incident EDS. Despite this, the seven-variable model could be used to stratify risk for subsequent development of EDS, which could prove instrumental in providing appropriate patient education, guiding safe behaviours and determining treatments. Because of the role of tau as a biomarker of neurodegeneration, it will be of great interest in future analyses to evaluate whether CSF tau values increase at greater rates in those with EDS.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size and comprehensive longitudinal clinical and biomarker assessments. Limitations include the subjective evaluation of EDS, without objective confirmation, particularly because objective and subjective EDS outcomes are often disparate in PD.4 However, subjective EDS consistently shows clinically important consequences and reduced quality of life and is a useful research tool for prognostic stratification.4,5 Similarly, RBD and OSA were based on self-report and not polysomnographically confirmed, and treatment status of OSA was not available. Another limitation is that longitudinal CSF data analysis on this cohort in years 2 and 3 is pending. Finally, the lack of a questionnaire dedicated to addressing nocturnal sleep characteristics may limit our ability to fully understand all the factors that could contribute to development of EDS over time.

In conclusion, we present the largest longitudinal, case–control study of clinical and biological variables associated with EDS in patients with de novo unmedicated PD at baseline and predictors of incident development of EDS in PD. Our findings indicate that EDS increases over time in PD, while remaining stable in HC. EDS is associated with non-TD phenotype, autonomic dysfunction, depression, anxiety, pRBD and increasing dopaminergic medications. Predictors of incident development of EDS include autonomic dysfunction, anxiety and CSF p-tau/t-tau. Taken together, our findings suggest that EDS is a potential manifestation of more severe brainstem neurodegeneration and increasing dopaminergic therapy in patients with early PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

PPMI—a public–private partnership—is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including AbbVie, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Covance, GE Healthcare, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Meso Scale Discovery, Pfizer, Piramal, Roche, Servier, UCB and Golub Capital. Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) database (www.ppmi-info.org/data). For up-to-date information on the study, visit www.ppmi-info.org.

Funding AWA receives grant funding from the NIH NINDS (K23 NS080912), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG022838) and the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1 TR00141). LMC (i) receives support from the NIH (P50 NS053488), (ii) receives support as site principal investigator of the Parkinson’s Progression Marker’s Initiative and (iii) receives royalties from Wolters Kluwer (for book authorship). JDL receives funding from CHDI, Michael J. Fox Foundation and NIH. RP received grants from the Fonds de la Recherche en Sante Quebec, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Parkinson Society, the Weston-Garfield Foundation and the Webster Foundation, as well as funding for consultancy from Biotie, Roche and Biogen. WO is a Hertie Senior Research Professor supported by the Charitable Hertie Foundation, Frankfurt/Main, Germany. TS received research funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the National Institutes of Health and the National Parkinson Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests AWA is an investigator for studies sponsored by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and Abbvie. JDL has a consulting agreement with NeuroPhage and is a paid consultant for Roche Pharma and Azevan Pharmaceuticals. BH received honoraria as a consultant, for advisory board and/or for speaking for UCB, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Lilly, Axovant and Mundipharma, and Travel Support from Habel Medizintechnik and Vivisol, Austria. GM is an investigator for studies sponsored by UCB Pharma Brussels, Novartis, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Paul Ehrlich Institute Langen/Germany, Jazz Pharma/USA and Bioprojet; serves on speaker’s bureau for UCB Pharma Brussels; and is on the advisory board of UCB Pharma. RP receives speaker fees from Boehringer, Novartis Canada and Teva Neurosciences. SL is employed by Molecular NeuroImaging, LLC. KM has ownership in inviCRO, LLC and a consultant for Pfizer, GE Healthcare, Lilly, BMS, Piramal, Biogen, Prothena, Roche, Neuropore, US WorldMeds, Neurophage, UCB, Oxford Biomedica and Lysosomal Therapetic, Inc. TS has received consulting honoraria from National Parkinson Foundation, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Harbor, UCB, IMPAX, Acadia, Lundbeck, Eli Lilly and Company, Allergan, Merz Inc and US WorldMeds.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2011;26:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simuni T, Caspell-Garcia C, Coffey C, et al. Correlates of excessive daytime sleepiness in de novo Parkinson’s disease: A case control study. Mov Disord 2015;30:1371–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knipe MD, Wickremaratchi MM, Wyatt-Haines E, et al. Quality of life in young-compared with late-onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2011. 26 2011 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chahine LM, Amara AW, Videnovic A. A systematic review of the literature on disorders of sleep and wakefulness in Parkinson’s disease from 2005 to 2015. Sleep Med Rev 2016;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meindorfner C, Körner Y, Möller JC, et al. Driving in Parkinson’s disease: mobility, accidents, and sudden onset of sleep at the wheel. Mov Disord 2005;20:832–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu K, van Hilten JJ, Marinus J. Course and risk factors for excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;24:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breen DP, Williams-Gray CH, Mason SL, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness and its risk factors in incident Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:233–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbaan D, van Rooden SM, Visser M, et al. Nighttime sleep problems and daytime sleepiness in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rye DB. Excessive daytime sleepiness and unintended sleep in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2006;6:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato S, Watanabe H, Senda J, et al. Widespread cortical and subcortical brain atrophy in Parkinson’s disease with excessive daytime sleepiness. J Neurol 2012;259:318–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative. The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol 2011;95:629–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gjerstad MD, Alves G, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinson disease: is it the drugs or the disease? Neurology 2006;67:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tholfsen LK, Larsen JP, Schulz J, et al. Development of excessive daytime sleepiness in early Parkinson disease. Neurology 2015;85:162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao J, Huang X, Park Y, et al. Daytime napping, nighttime sleeping, and Parkinson disease. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1032–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagell P, Broman JE. Measurement properties and hierarchical item structure of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in Parkinson’s disease. J Sleep Res 2007;16:102–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monaca C, Duhamel A, Jacquesson JM, et al. Vigilance troubles in Parkinson’s disease: a subjective and objective polysomnographic study. Sleep Med 2006;7:448–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poryazova R, Benninger D, Waldvogel D, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinson’s disease: characteristics and determinants. Eur Neurol 2010;63:129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Högl B, Arnulf I, Comella C, et al. Scales to assess sleep impairment in Parkinson’s disease: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord 2010;25:2704–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnulf I, Konofal E, Merino-Andreu M, et al. Parkinson’s disease and sleepiness: an integral part of PD. Neurology 2002;58:1019–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord 2008;23:2129–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stebbins GT, Goetz CG, Burn DJ, et al. How to identify tremor dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty groups with the movement disorder society unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale: comparison with the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov Disord 2013;28:668–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967;17:427–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwab R, England A. Projection technique for evaluating surgery in Parkinson’s disease. In: Gillingahm F, Donaldson I, eds. Third Symposium of Parkinson’s Disease Edinburgh, Scotland: E&S Livingstone, 1969:152–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weintraub D, Oehlberg KA, Katz IR, et al. Test characteristics of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in Parkinson disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:169–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Forjaz MJ, Frades-Payo B, et al. Independent validation of the scales for outcomes in Parkinson’s disease-autonomic (SCOPA-AUT). Eur J Neurol 2010;17:194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendall PC, Finch AJ, Auerbach SM, et al. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: a systematic evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1976;44:406–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E, Papay K, et al. Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive disorders in Parkinson’s Disease-Rating Scale. Mov Disord 2012;27:242–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stiasny-Kolster K, Mayer G, Schäfer S, et al. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire—a new diagnostic instrument. Mov Disord 2007;22:2386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolitho SJ, Naismith SL, Terpening Z, et al. Investigating rapid eye movement sleep without atonia in Parkinson’s disease using the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire. Mov Disord 2014;29:736–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:2649–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang JH, Irwin DJ, Chen-Plotkin AS, et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 1–42, T-tau, P-tau181, and α-synuclein levels with clinical features of drug-naive patients with early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:1277–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB, Blackstone EH, et al. Random survival forests. Ann Appl Stat 2008;2:841–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simuni T, Long JD, Caspell-Garcia C, et al. Predictors of time to initiation of symptomatic therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2016;3:482–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins GS, de Groot JA, Dutton S, et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bogan RK, Roth T, Schwartz J, et al. Time to response with sodium oxybate for the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness and cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnulf I, Neutel D, Herlin B, et al. Sleepiness in Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson disease. Sleep 2015;38:1529–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Post B, Merkus MP, de Haan RJ, et al. Prognostic factors for the progression of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Mov Disord 2007;22:1839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller ML, Bohnen NI. Cholinergic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2013;13:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sulzer D, Surmeier DJ. Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2013;28:715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marras C, Chaudhuri KR. Nonmotor features of Parkinson’s disease subtypes. Mov Disord 2016;31:1095–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauerbier A, Jenner P, Todorova A, et al. Non motor subtypes and Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;22(Suppl 1):S41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anang JB, Gagnon JF, Bertrand JA, et al. Predictors of dementia in Parkinson disease: a prospective cohort study. Neurology 2014;83:1253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erro R, Pappatà S, Amboni M, et al. Anxiety is associated with striatal dopamine transporter availability in newly diagnosed untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:1034–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seibyl JP, Marek KL, Quinlan D, et al. Decreased single-photon emission computed tomographic [123I]beta-CIT striatal uptake correlates with symptom severity in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 1995;38:589–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Happe S, Baier PC, Helmschmied K, et al. Association of daytime sleepiness with nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration in early Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 2007;254:1037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wienecke M, Werth E, Poryazova R, et al. Progressive dopamine and hypocretin deficiencies in Parkinson’s disease: is there an impact on sleep and wakefulness? J Sleep Res 2012;21:710–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.