Abstract

Objective

To date, no randomised trials have compared the efficacy of vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy with other standard regimens for Helicobacter pylori treatment. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy of the 7-day vonoprazan and low-dose amoxicillin dual therapy as a first-line H. pylori treatment, and compared this with vonoprazan-based triple therapy.

Design

This prospective, randomised clinical trial was performed at seven Japanese institutions. Patients with H. pylori–positive culture test and naive to treatment were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either VA-dual therapy (vonoprazan 20 mg+amoxicillin 750 mg twice/day) or VAC-triple therapy (vonoprazan 20 mg+amoxicillin 750 mg+clarithromycin 200 mg twice/day) for 7 days, with stratification by age, sex, H. pylori antimicrobial resistance and institution. Eradication success was evaluated by 13C-urea breath test at least 4 weeks after treatment.

Results

Between October 2018 and June 2019, 629 subjects were screened and 335 were randomised. The eradication rates of VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies were 84.5% and 89.2% (p=0.203) by intention-to-treat analysis, respectively, and 87.1% and 90.2% (p=0.372) by per-protocol analysis, respectively. VA-dual was non-inferior to VAC-triple in the per-protocol analysis. The eradication rates in strains resistant to clarithromycin for VA-dual were significantly higher than those for VAC-triple (92.3% vs 76.2%; p=0.048). The incidence of adverse events was equal between groups.

Conclusion

The 7-day vonoprazan and low-dose amoxicillin dual therapy provided acceptable H. pylori eradication rates and a similar effect to vonoprazan-based triple therapy in regions with high clarithromycin resistance.

Trial registration number

UMIN000034140.

Keywords: helicobacter pylori - treatment, antibiotics - clinical trials, gastric inflammation, clinical trials

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Macrolides, including clarithromycin, readily induce changes in the resistome of Helicobacter pylori, and the clarithromycin resistance of H. pylori is high and increasing worldwide.

Usage of clarithromycin should be discontinued as an empirical treatment in wide-scale strategies for H. pylori infection.

Vonoprazan strongly inhibits gastric acid secretion, and vonoprazan-based triple therapy (VAC-triple) achieves sufficient eradication rates and high safety.

What are the new findings?

Vonoprazan and low-dose amoxicillin dual therapy for 7 days (VA-dual) is a regimen with minimal usage of antibiotics and is simpler than current H. pylori therapies.

VA-dual achieved acceptable eradication rates of 85% in intention-to-treat and 87% in per-protocol analyses.

VA-dual achieved an eradication rate of over 85% for both clarithromycin-susceptible and clarithromycin-resistant strains, and achieved a higher eradication rate than VAC-triple against clarithromycin-resistant strains.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

In the era of growing antimicrobial resistance, VA-dual is a potential new first-line H. pylori therapy for cases of high clarithromycin resistance because it provides an acceptable eradication rate and high safety, and will have a potentially less negative impact on future antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection is common chronic bacterial infections in humans, affecting approximately 50% of the global population.1 Although the prevalence of H. pylori is generally declining, the prevalence of the infection and the reinfection rates remain high in several regions.2 As H. pylori infection causes gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue and gastric cancer, H. pylori eradication treatment is performed worldwide to improve and reduce these conditions.3–5

The eradication effect of H. pylori treatment has decreased owing to increasing its antimicrobial resistance. Recent international guidelines recommend four-drug combination therapies containing 2–3 kinds of antibiotics for 10–14 days as the first-line treatment for H. pylori in regions with high clarithromycin (CLA) resistance to overcome its antimicrobial resistance.6–8 However, these quadruple regimens have several disadvantages, including severe side effects, high cost and low compliance due to the use of multiple antibiotic agents for a long period; these features have hampered its implementation in routine clinical practice. Furthermore, the use of multiple antibiotic agents in H. pylori treatment can increase the risk of future antimicrobial resistance. Thus, novel regimens and approaches enabling minimal antibiotic usage and shorter treatment duration are required to prevent antimicrobial resistance while achieving sufficient eradication rates.

Dual therapy composed of a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) and amoxicillin (AMO) is the simplest regimen for H. pylori treatment and, because it is a single antibiotic therapy, we expect it will not contribute to the development of H. pylori antibiotic resistance. Maintaining a near-neutral pH in the stomach during eradication therapy is important to succeed dual therapy regimen. Vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, provides a stronger and longer-lasting effect on the gastric acid suppression than other PPIs.9 Therefore, vonoprazan is expected to be more effective than other PPIs when used in dual therapy with AMO for the H. pylori eradication treatment. However, the efficacy of such dual therapy for H. pylori eradication has not been studied yet and no randomised studies have assessed the efficacy of dual therapy consisting of vonoprazan and AMO for H. pylori eradication.

The aim of this proof of concept study was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of the 7-day vonoprazan and low-dose AMO dual therapy (VA-dual) and to compare it with a 7-day vonoprazan, AMO and CLA triple therapy (VAC-triple) as the first-line treatments for H. pylori.

Methods

Study design and ethical issues

This study was designed as a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/) on 14 September 2018.

Study population

Consecutive patients who underwent oesophagogastroduodenoscopy to evaluate the cause of any abdominal symptom or screening for upper GI cancer were recruited in seven institutions in Japan between October 2018 and June 2019. All the 629 recruited patients were screened and underwent H. pylori culture test through biopsy of the gastric mucosa. Patients were eligible if they were aged 20–79 years and had confirmed H. pylori infection by culture test. Patients were excluded if they had any of the following: history of receiving H. pylori eradication therapy; allergy to any of the study drugs; history of gastric surgery; use of PPIs, antibiotics or steroids that could not have been discontinued during this study; pregnancy or breast feeding; lack of informed consent.

H. pylori strains and antimicrobial susceptibility test

At least two biopsies were collected from the gastric antrum and corpus to isolate H. pylori strains. Biopsy specimens were used to inoculate Helicobacter selective agar medium (Nissui Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan) containing 10% laked horse blood and incubated under microaerophilic condition (85% N2, 10% CO2, 5% O2) at 37℃ for 7–10 days. The culture was considered positive if one or more colonies showed Gram negativity, urease, oxidase, catalase, and spiral or curved rods in morphology.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of H. pylori isolates was determined by the microbroth dilution method using Eiken Chemical dry plates (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan). Each well of a 96-well microplate was coated with twofold serial dilutions of AMO and CLA and air-dried. A saline suspension of the test strain was added to each well, and the cultures were incubated at 35℃ for 3 days in a microaerophilic atmosphere (O2, 10%; CO2, 5%). The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of a test antibiotic that completely inhibited visible bacterial growth. MIC values of ≥0.12 µg/mL for AMO and ≥1 µg/mL for CLA were defined as resistance break points.

Randomisation and trial intervention

The 335 eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either VA-dual or VAC-triple in a 1:1 allocation ratio. VA-dual consisted of 20 mg vonoprazan (Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) twice daily and 750 mg AMO twice daily for 7 days. The VAC-triple consisted of 20 mg vonoprazan twice daily, 750 mg AMO twice daily and 200 mg CLA twice daily for 7 days. AMO and CLA used in both therapies were from Takeda Pharmaceutical or of generic branding. The treatment group was randomly assigned by the UMIN Medical Research Support INDICE Cloud System. Randomisation was performed by dynamic balancing using the minimisation method, with stratification by age (<60 years vs ≥60 years), sex (male vs female), AMO resistance of H. pylori (MIC <0.12 µg/mL vs MIC ≥0.12 µg/mL), CLA resistance of H. pylori (MIC <1 µg/mL vs MIC ≥1 µg/mL) and institution. A computer-generated randomisation list was used, which was preordered for each stratum. The randomisation sequence was concealed for all investigators. Patients and investigators were not blinded to the allocated treatment group.

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint in this study was the H. pylori eradication rate in the VA-dual and VAC-triple groups. Eradication success was evaluated at least 4 weeks after the treatment period using the 13C-urea breath test (UBT) (UBIT tablet; Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) with success defined as a result of <2.5‰. Prior to the UBT, patients were not permitted to take PPIs or any antibiotics. The primary analysis was determined by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. The ITT analysis was defined to include all randomised patients. The patients who were lost to follow-up or did not undergo UBT were regarded as treatment failures in the ITT analysis. The PP analysis included patients who achieved >80% (6 days) of drug compliance and underwent UBT. Drug compliance was recorded in a specific questionnaire form by patients.

The secondary endpoints were the frequency and severity of adverse events and the comparison of the eradication rates between VA-dual and VAC-triple according to CLA susceptibility or MIC values of AMO. The adverse events induced by the study drugs were documented in a specific questionnaire form filled in by patients for 14 days from the start of the therapy. When patients reported any adverse event in the questionnaire form, the investigators inquired them and assessed the severity using the 1 to 4 grading system based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) V.5.0.10 The outcomes in this study were not changed after the trial commenced.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

In previous studies, the eradication rates were between 94%11 and 91%12 in similar regimens for first-line H. pylori treatment. We assumed H. pylori eradication rates of 90% in both VA-dual and VAC-triple groups and used non-inferiority design in this study; statistically, a non-inferiority margin of −10% was the recommended level in a non-inferiority anti-infective trial13 and in H. pylori treatment trials,14–16 although a non-inferiority margin of −10%, compared with the 90% of estimated eradication rate of VAC-triple, may be clinically insufficient. Assuming a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.025 (one-sided), at least 284 patients (142 patients in each group) would be required in the non-inferiority trial. Assuming a follow-up loss of 10%, a sample size of 320 patients (160 patients in each group) was planned.

Comparative non-inferiority of the two groups was assessed through the derivation of a two-sided 95% CI and hypothesis testing (one-sided μ-test). Differences between groups were analysed using Pearson’s χ2 test and Student’s t-test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. All p values were two-sided, except for the test of non-inferiority, and were considered statistically significant if p value <0.05. All analyses were computed using the R V.3.5.2 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient enrolment and baseline characteristics

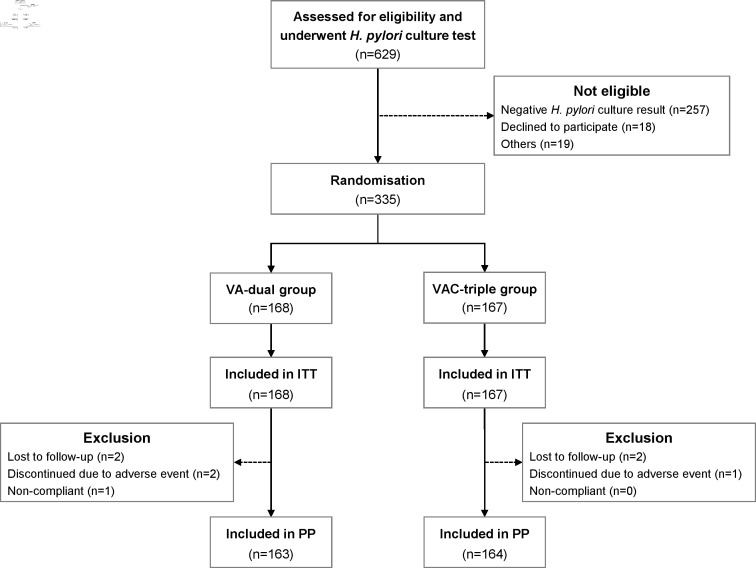

The flow chart for patients enrolled in this study is shown in figure 1. In total, 629 patients were assessed for eligibility and underwent H. pylori culture test within the 9-month study period; 335 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to either the VA-dual or the VAC-triple treatment group. The baseline demographic data, clinical characteristics and rates of antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori were not significantly different between the two groups (table 1). Two patients in the VA-dual group and two patients in the VAC-triple group were lost to follow-up and did not undergo UBT.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient enrolment. ITT, intention-to-treat; PP, per protocol; VA-dual, vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy; VAC-triple, vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and prevalence of antimicrobial resistance of study patients

| VA-dual (n=168) |

VAC-triple (n=167) |

P value | |

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 61.2±11.5 | 61.3±10.4 | 0.912 |

| Range | 34–79 | 26–79 | |

| Sex (male/female) | 106/62 | 103/64 | 0.789 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean±SD) | 23.9±3.2 | 23.9±3.4 | 0.979 |

| Range | 16.3–35.7 | 16.1–33.3 | |

| Disease-associated Helicobacter pylori | |||

| Gastric ulcer | 18 (10.7%) | 25 (15.0%) | 0.244 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 23 (13.7%) | 20 (12.0%) | 0.639 |

| ER for gastric neoplasia | 9 (5.4%) | 6 (3.6%) | 0.435 |

| MALT lymphoma | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.318 |

| Cigarette smoking | 38 (22.6%) | 41 (24.6%) | 0.677 |

| Alcohol drinking | 25 (14.9%) | 29 (17.4%) | 0.536 |

| Daily use PPI before the trial | 10 (6.0%) | 6 (3.6%) | 0.311 |

| Antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori | |||

| Amoxicillin | 0 | 0 | – |

| Clarithromycin | 40 (23.8%) | 42 (25.1%) | 0.776 |

BMI, body mass index; ER, endoscopic resection; MALT lymphoma, mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor; VAC-triple, vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy; VA-dual, vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy.

H. pylori eradication rates

The successful H. pylori eradication rates for each therapy are shown in table 2. In the ITT analysis, the H. pylori eradication rate was 84.5% (95% CI 78.2% to 89.6%, 142/168) in the VA-dual group and 89.2% (95% CI 83.5% to 93.5%, 149/167) in the VAC-triple group. In the PP analysis, the H. pylori eradication rate was 87.1% (95% CI 81.0% to 91.8%, 142/163) and 90.2% (95% CI 84.6% to 94.3%, 148/164) in the VA-dual and the VAC-triple groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Eradication rates of each therapy group

| Analysis | VA-dual | VAC-triple | Difference from VAC-triple (adjusted 95% CI for difference) |

P value for difference* | P value for non-inferiority† |

| ITT | 84.5% (142/168) | 89.2% (149/167) | 4.7% (–11.8% to 2.4%) | 0.203 | 0.073 |

| 95% CI | 78.2% to 89.6% | 83.5% to 93.5% | |||

| PP | 87.1% (142/163) | 90.2% (148/164) | 3.1% (–9.9% to 3.7%) | 0.372 | 0.024 |

| 95% CI | 81.0% to 91.8% | 84.6% to 94.3% |

*The p values were obtained from two-sided comparisons of difference between the VA-dual group and VAC-triple group.

†The p values were obtained from one-sided test comparisons of non-inferiority between the VA-dual group and VAC-triple group.

ITT, intention-to-treat; PP, per protocol; VAC-triple, vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy; VA-dual, vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy.

The lower bound of the 95% CI for the difference of eradication rates of the VA-dual group from VAC-triple group was greater than the prespecified non-inferiority margin in the PP analysis. However, in the ITT analysis, it was less than the non-inferiority margin, and the VA-dual group did not reach statistically significant noninferiority compared with the VAC-triple group.

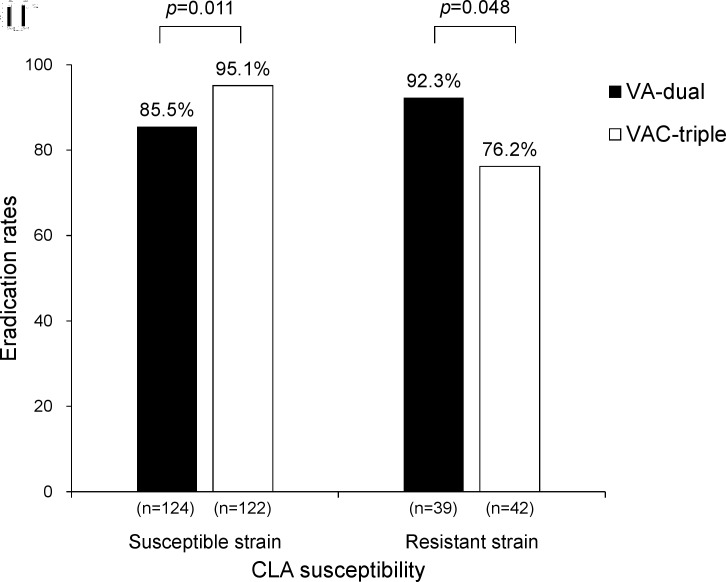

Eradication rates according to antimicrobial susceptibility of H. pylori

The resistance rate of H. pylori to CLA was 24.5% (82/335). Subgroup analysis was performed to determine the effect of CLA resistance on the eradication rate in the PP population (figure 2). In the CLA-susceptible strain, the eradication rate in the VAC-triple group was significantly higher than that in the VA-dual group (85.5% vs 95.1%, p=0.011). In contrast, for the CLA-resistant strain, the eradication rates in the VA-dual group were significantly higher than those in the VAC-triple group (92.3% vs 76.2%, p=0.048). The eradication rates of CLA-susceptible and CLA-resistant strains were similar in the VA-dual group (85.5% vs 92.3%, p=0.267). The eradication rate of the CLA-susceptible strain was significantly higher than that of the CLA-resistant strain in the VAC-triple group (95.1% vs 76.2%, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Eradication rates of each therapy groups in the presence of clarithromycin resistance in PP population. CLA, clarithromycin; PP, per protocol; VA-dual, vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy; VAC-triple, vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy.

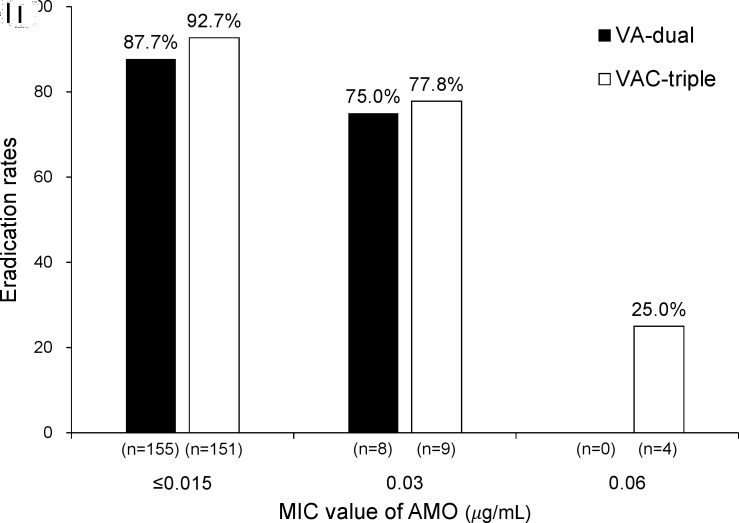

The AMO MIC values were categorised into three groups: ≤0.015, 0.03 or 0.06 µg/mL. The proportions of each MIC value were 93.1% (312/335), 5.7% (19/335) and 1.2% (4/335), respectively. The eradication rates in the VA-dual and VAC-triple groups for each AMO MIC group in the PP population are shown in figure 3. The difference in eradication rates between the ≤0.015 and 0.03 groups was not significant for the two therapies (VA-dual: 87.7% vs 75.0%, p=0.294; VAC-triple: 92.7% vs 77.8%, p=0.111). In the VAC-triple group, the eradication rate in the 0.06 of MIC group was significantly lower than that in the ≤0.015 of MIC group (25.0% vs 92.7%, p<0.001) and also lower than that in the 0.03 of MIC group, although not statistically significant (25.0% vs 77.8%, p=0.071).

Figure 3.

Eradication rates of each therapy groups according to MIC value of amoxicillin in PP population. AMO, amoxicillin; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; PP, per protocol; VA-dual, vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy; VAC-triple, vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy.

Compliance and adverse events

Three patients in the VA-dual group and one patient in the VAC-triple group failed to take at least 80% of the study drugs. Among these four patients, two patients in the VA-dual group discontinued the treatment because of skin rash. One patient in the VAC-triple group discontinued the treatment because of diarrhoea and nausea, but underwent UBT, and eradication success was confirmed.

The adverse events of all patients are shown in table 3. The total adverse event rates were similar between the VA-dual and VAC-triple groups (27.4% vs 30.5%, p=0.524). Overall, 91.4% of the adverse events were mild (grade 1 in CTCAE) and 8.6% were moderate (grade 2 in CTCAE). There was no indication of severe adverse events (grades 3–4 in CTCAE). All adverse events, except skin rash, were spontaneously cured without intervention. Four patients who developed a skin rash were cured with oral or external anti-allergic agents or low-dose steroids. No patients were hospitalised because of adverse events.

Table 3.

Adverse events in each therapy group

| Adverse event | VA-dual (n=168) |

VAC-triple (n=167) |

P value |

| Diarrhoea | 16 (9.5%) | 25 (15.0%) | 0.128 |

| Moderate | 1 | 3 | |

| Bloating | 20 (11.9%) | 14 (8.4%) | 0.286 |

| Moderate | 1 | 0 | |

| Constipation | 10 (6.0%) | 8 (4.8%) | 0.637 |

| Skin rash | 9 (5.4%) | 5 (3.0%) | 0.280 |

| Moderate | 4 | 1 | |

| Nausea | 5 (3.0%) | 4 (2.4%) | 0.742 |

| Moderate | 0 | 1 | |

| Abdominal pain | 6 (3.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.155 |

| Moderate | 1 | 0 | |

| Dysgeusia | 3 (1.8%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0.994 |

| Oral mucositis | 0 | 6 (3.6%) | 0.013 |

| Others | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.995 |

| Total patients | 46 (27.4%) | 51 (30.5%) | 0.524 |

VAC-triple, vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin triple therapy; VA-dual, vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomised controlled study to reveal the efficacy of a 7-day vonoprazan and low-dose AMO dual therapy. The VA-dual therapy provided acceptable H. pylori eradication rates of 85% in the ITT analysis and 87% in the PP analysis. The eradication rates of the CLA-resistant strain in the VA-dual therapy were higher than those in the VAC-triple therapy. Moreover, adverse events hindered the compliance of VA-dual therapy in only 1%.

Standard triple therapy (STT) consisting of a PPI, AMO and CLA is no longer effective in many regions of the world owing to increasing CLA resistance of H. pylori; four-drug combination therapy such as bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (BQT) or concomitant quadruple therapy (CQT) are currently recommended as first-line treatments in areas with high CLA resistance.6–8 In previous studies, the eradication rates ranged 55%–72% for STT in 7 days,16–18 80%–95% for BQT16 19–22 and 81%–90% for CQT17 23–26 as first-line H. pylori eradication treatments. The eradication rates of VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies in this study were higher than those previously reported for the 7-day STT and as high as the ones reported for BQT and CQT although the CLA resistance rate was 25% in this study. The high eradication rates achieved with the VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies could be attributable to strong gastric acid suppression and the maintenance of high pH in the stomach provided by vonoprazan. Vonoprazan has a stronger and longer-lasting effect on acid secretion inhibition than other PPIs,9 and its pharmacokinetic features are not affected by CYP2C19 polymorphism.27 H. pylori eradication rates of 86%–93% were achieved with a regimen similar to VAC-triple therapy as first-line treatment.12 28 29 Another explanation for the high eradication rates for VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies could be related to the fact that the strain infecting the subjects was not resistant to AMO. H. pylori resistance rate to AMO is still lower than that to other antibiotics and is usually overlooked when determining the H. pylori treatment regimens. However, resistance to AMO substantially differs among world regions (38% in Africa region, 14% in Eastern Mediterranean region, 12% in Southeast Asia region, 8% in Americas region, and 0%–1% in European and Western Pacific regions).30 The resistance breakpoint was set to MIC ≥0.12 µg/mL, which is a stricter cut-off value than the commonly used MIC breakpoint of 0.5 μg/mL31; because there was no AMO resistance in this study, VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies could achieve high eradication rates of H. pylori. Thus, both VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies could be alternative regimens as first-line H. pylori treatment in the regions with no AMO resistance. However, as the inverse relationship between H. pylori eradication rate and AMO MIC values was revealed in this study, the efficacy of both VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies might be limited to the regions with moderate to high AMO resistance.

A dual therapy consisting of PPI and AMO was first reported in the 1990s as a first-line treatment against H. pylori infection (table 4). The efficacy of a low-dose and/or less frequent dual therapy consisting of AMO (2.0 g/day or less) and PPI (twice/day or less) resulted in unacceptable eradication rates.32–34 Recently, high-dose and high-frequency dual therapy, defined as the administration of both AMO (≥2.0 g/day) and PPI (at least twice daily) for 14 days, has been reported to have greater H. pylori eradication efficacy as first-line therapy.35–38 However, side effects and poor patient compliance due to high dose, high administration frequency and long duration of treatment are the most common setbacks. Thus, the high-dose and high-frequency AMO–PPI dual therapy has been subsequently used as a rescue/salvage treatment. As the important factor to a successful dual therapy regimen is to maintain a near-neutral pH in the stomach to make H. pylori sensitive to AMO and vonoprazan has a stronger effect on acid secretion inhibition than other PPIs, it is expected to be more effective when used in combination with AMO for eradication of H. pylori. We demonstrated that VA-dual therapy achieved 87% of eradication rates in PP analysis and was non-inferior to VAC-triple therapy. However, the eradication effect of VA-dual did not achieve the clinically sufficient eradication rate of 90%. Further, the 10% non-inferiority margin, compared with 90% of eradication rate for VAC-triple therapy, may be clinically inappropriate because this setting means that the lower bound of the 95% CI of the VA-dual eradication rates could be 80%, which is also insufficient for H. pylori treatment in clinical practice. Another key parameter to the success of a dual therapy regimen is to maintain steady AMO plasma concentrations above the MIC level for its bactericidal effect against H. pylori. The results of a retrospective study in which dual therapy (vonoprazan 20 mg twice daily and AMO 500 mg three times daily for 7 days) provided an eradication rate of 93% as first-line treatment39 suggested that high administration frequency of AMO could improve the eradication rate in vonoprazan-based dual therapy to values similar to those of high-dose and high-frequency AMO–PPI dual therapy. Thus, further adjustments in the administration frequency and dose of AMO are necessary to improve the eradication effect of the VA-dual therapy.

Table 4.

Studies of PPI and amoxicillin dual therapies as first-line Helicobacter pylori treatment

| Studies | Study design | Sample size | Dose of PPI | Dose of amoxicillin | Treatment duration (days) | Eradication rates (ITT) |

| Koizumi W et al 32 | RCT | 31 | Omeprazole 20 mg qd | 500 mg tid | 14 | 42% |

| Cottrill MR et al 33 | RCT | 85 | Omeprazole 40 mg qd | 1000 mg twice daily | 14 | 44% |

| Wong BC et al 34 | RCT | 75 | Lansoprazole 30 mg twice daily | 1000 mg twice daily | 14 | 57% |

| Schwartz H et al 35 | RCT | 60 | Lansoprazole 30 mg twice daily | 1000 mg tid | 14 | 45% |

| Schwartz H et al 35 | RCT | 60 | Lansoprazole 30 mg tid | 1000 mg tid | 14 | 70% |

| Yang J et al 36 | RCT | 116 | Esomeprazole 20 mg qid | 750 mg qid | 14 | 88% |

| Yu L et al 37 | RCT | 80 | Esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily | 1000 mg tid | 14 | 93% |

| Yang JC et al 38 | RCT | 150 | Rabeprazole 20 mg qid | 750 mg qid | 14 | 95% |

| Furuta et al 39 | Retrospective study | 56 | Vonoprazan 20 mg twice daily | 500 mg tid | 7 | 93% |

| Present study | RCT | 168 | Vonoprazan 20 mg twice daily | 750 mg twice daily | 7 | 85% |

ITT, intention-to-treat; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor; qd, once daily; qid, four times daily; RCT, randomised controlled trial; tid, three times daily.

The results of the subgroup analysis by CLA susceptibility in this study were unexpected. The eradication rate of the CLA-resistant strain achieved with VA-dual therapy was significantly higher than that achieved with VAC-triple therapy. As the VA-dual therapy consists of fewer antibiotic agents than the VAC-triple therapy, it is unlikely that the eradication rate of VA-dual therapy is higher than that of VAC-triple therapy, regardless of the antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori. This difference in eradication of the CLA-resistant strain between the two treatment groups can be attributed to chance as the p value was borderline and the sample size was small. The AMO MIC cut-off value may also account for this difference. Although none of the patients was infected with an AMO-resistant strain, seven patients receiving VAC-triple therapy and two patients receiving VA -dual therapy had MIC of ≥0.03 µg/mL in group with patients with CLA-resistant strains. The subgroup analysis of eradication rates according to the MIC of AMO showed that the eradication rate for the VAC-triple therapy in the 0.06 of MIC group was lower than that in the ≤0.015 and 0.03 of MIC group. This disparity in the proportion of AMO MIC between the groups potentially affected the eradication rates and resulted in a lower eradication rate in the VAC-triple group. Another possible explanation for the CLA-resistant eradication difference observed between the VA-dual and VAC-triple therapies regards the pharmacokinetic interaction of vonoprazan and CLA. Because both vonoprazan and CLA are metabolised by the same hepatic enzyme (cytochrome P450 3A4), administering both drugs together increases the maximum plasma concentration and the area under the plasma concentration–time curve of vonoprazan by 1.5-fold to 1.9-fold in comparison with the administration of vonoprazan alone.40 Vonoprazan has a strong gastric acid inhibitory effect and the gastric pH level often exceeds 7 even when administered alone.9 27 Thus, when vonoprazan is administered with CLA, the maximum pH level may increase or the duration of this effect may be extended. H. pylori grows at a narrow external pH range between 6 and 7 and is sensitive to growth-dependent antibiotics including AMO. Previously, the optimal pH for H. pylori growth was studied in vitro and it was reported that the growth of this bacterium was poorer at pH 7.9 than at pH 7.2.41 Thus, the vonoprazan–CLA interaction might cause suboptimal gastric acid pH levels (ie, >7), resulting in a decrease in the H. pylori sensitivity to AMO in the VAC-triple therapy.

Another benefit of VA-dual therapy is related to the optimal the use of antibiotic agents, which, in the long term, will have minimal impact on the antimicrobial resistance scenario. H. pylori antimicrobial resistance is a global priority. WHO published its first-ever list of antimicrobial resistant ‘priority pathogens’ in 2017, and CLA-resistant H. pylori was categorised as a high-priority bacterium in the same tier as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium.42 Macrolides, including CLA, are commonly used to treat bacterial infectious diseases; however, they can readily induce alterations in the resistome of bacteria, including H. pylori. The use of long-acting macrolides is significantly associated with the resistance of H. pylori to CLA43 and previous exposure of CLA has a negative impact on the success of some H. pylori treatments.44 45 The international guidelines recommend that clarithromycin be no longer used in empirical treatment for H. pylori infection. The resistance rates to metronidazole and levofloxacin have increased >15% in many regions of the world in recent years adding to the observed increase in CLA resistance.30 Thus, given the alarming increase of the rates of resistance to CLA and to various families of antibiotics, treatment strategies have to be re-evaluated and the best approach relies on the appropriate use of antibiotics for the treatment of H. pylori. Therefore, antimicrobial susceptibility testing is the best way to optimise and reduce antibiotics for H. pylori eradication treatment as well as the treatment of other common infections. However, antimicrobial susceptibility testing is not performed routinely in the clinical practice because of the invasiveness of the endoscopy procedure, the limited availability of laboratory culture facilities and cost concerns. The VA-dual therapy offers an alternative regimen for H. pylori eradication treatment in the era of increasing antimicrobial resistance. We demonstrated that the VA-dual therapy provides acceptable H. pylori eradication rates. As it is a single antibiotic therapy and antibiotic consumption is low, with no use of CLA, and H. pylori is hardly resistant to AMO, we expect that VA-dual therapy will not contribute to the increase in antimicrobial resistance rates. The results of this study suggest that VA-dual therapy can be used as first-line H. pylori empirical treatment, and that susceptibility-based therapies using multiple antibiotic agents should be used as rescue therapy only in cases where the VA-dual therapy fails. This treatment strategy should limit unnecessary antibiotic usage, prevent widespread resistance development of other organisms and reduce the costs of H. pylori treatment.

This study design has several advantages: first, the study was a randomised controlled trial corrected from multiple centres; and second, the antibacterial susceptibility of H. pylori was confirmed in all enrolled patients and was used as stratification factor in randomisation. However, owing to the open-label nature of the study design, the lack of blinding may have influenced the reporting of side effects. In addition, only Japanese patients enrolled in this study; as vonoprazan has been introduced recently outside of Japan, studies with a double-blind design should also be performed in other countries.

In conclusion, the 7-day vonoprazan and low-dose AMO dual therapy provided acceptable H. pylori eradication rates and was similar to the effect of vonoprazan-based triple therapy as a first-line H. pylori eradication therapy in a country with high resistance to CLA. The VA-dual therapy has advantages, including single antibiotic and low antibiotic consumption; however, there is also the potential to improve its eradication effect through adjustments in the administration of AMO. Thus, further studies should be demanded to develop VA-dual therapy with proper adjustments and to establish new first-line H. pylori eradication treatments in the era of growing antimicrobial resistance.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Mitsuru Esaki, Hitoshi Shibuya and Toshiki Horii from Nihon University School of Medicine, Toyotaka Kasai and Hiroyuki Eto from Fukaya Red Cross Hospital, and Yoshioki Yoda from Yamanashi Koseiren Health Care Center for collecting data and valuable assistance in conducting this study, and Mikitaka Iguchi from Wakayama Medical University for conducting Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ShoSuzuki12

Contributors: SS, TG and CK planned and designed the study. SS and TG wrote the manuscript. SS, RI, HirI, YO, MasO, MN and KK had leadership in each institution and collected data. HisI, MotO and MK made critical revision of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was founded by Nihon University School of Medicine.

Competing interests: TG received honorarium from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the manufacturer of study drugs.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating unit, and the protocol was not changed after the trial commenced.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. De-identified data sets and protocol of the present study will be made available by reasonable request from the UMIN Individual Case Data Repository (https://www.umin.ac.jp/icdr/index.html).

References

- 1. Sjomina O, Pavlova J, Niv Y, et al. . Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2018;23:e12514 10.1111/hel.12514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leja M, Axon A, Brenner H. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2016;21:3–7. 10.1111/hel.12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sugano K. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 2019;22:435–45. 10.1007/s10120-018-0876-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doorakkers E, Lagergren J, Engstrand L, et al. . Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment and the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in a Western population. Gut 2018;67:2092–6. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sjomina O, Heluwaert F, Moussata D, et al. . Helicobacter pylori infection and nonmalignant diseases. Helicobacter 2017;22:e12408 10.1111/hel.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, et al. . Acg clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:212–39. 10.1038/ajg.2016.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, et al. . The Toronto consensus for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults. Gastroenterology 2016;151:e14:51–69. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, et al. . Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017;66:6–30. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sakurai Y, Mori Y, Okamoto H, et al. . Acid-inhibitory effects of vonoprazan 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 20 mg or rabeprazole 10 mg in healthy adult male subjects—a randomised open-label cross-over study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:719–30. 10.1111/apt.13325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Cancer Institute Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v5.0, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Furuta T, Yamade M, Uotani T, et al. . Tu1299—vonoprazan-based dual therapy with amoxicillin is as effective as the triple therapy for the eradication of H. pylori. Gastroenterology 2018;154:S-927 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)33125-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kusano C, et al. . The efficacy and tolerability of a triple therapy containing a potassium-competitive acid blocker compared with a 7-day PPI-based low-dose clarithromycin triple therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:949–56. 10.1038/ajg.2016.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Sullivan LM. Non-inferiority trials: design concepts and issues—the encounters of academic consultants in statistics. Stat Med 2002;22:169–86. 10.1002/sim.1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Q, Zhang W, Fu Q, et al. . Rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized non-inferiority trial of amoxicillin or tetracycline in bismuth quadruple therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1736–42. 10.1038/ajg.2016.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang W, Chen Q, Liang X, et al. . Bismuth, lansoprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole or clarithromycin as first-line Helicobacter pylori therapy. Gut 2015;64:1715–20. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier J-C, et al. . Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:905–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim BJ, Lee H, Lee YC, et al. . Ten-day concomitant, 10-day sequential, and 7-day triple therapy in first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized nationwide trial in Korea. Gut Liver 2019. [Epub ahead of print: 22 Jul 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim BJ, Yang Chang‐Hun, Song HJ, et al. . Online registry for nationwide database of Helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: correlation of antibiotic use density with eradication success. Helicobacter 2019;24:e12646 10.1111/hel.12646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liou J-M, Fang Y-J, Chen CC, et al. . Concomitant, bismuth quadruple, and 14-day triple therapy in the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 2016;388:2355–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31409-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fiorini G, Zullo A, Saracino IM, et al. . Pylera and sequential therapy for first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication: a culture-based study in real clinical practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30:621–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miehlke S, Frederking D, Günther T, et al. . Efficacy of three-in-one capsule bismuth quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in clinical practice in a multinational patient population. Helicobacter 2017;22:e12429 10.1111/hel.12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tursi A, Di Mario F, Franceschi M, et al. . New bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori: a first Italian experience in clinical practice. Helicobacter 2017;22:e12371 10.1111/hel.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molina-Infante J, Lucendo AJ, Angueira T, et al. . Optimised empiric triple and concomitant therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in clinical practice: the OPTRICON study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:581–9. 10.1111/apt.13069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNicholl AG, Marin AC, Molina-Infante J, et al. . Randomised clinical trial comparing sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in routine clinical practice. Gut 2014;63:244–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choe JW, Jung SW, Kim SY, et al. . Comparative study of Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of concomitant therapy vs modified quadruple therapy comprising proton-pump inhibitor, bismuth, amoxicillin, and metronidazole in Korea. Helicobacter 2018;23:e12466 10.1111/hel.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cosme A, Lizasoan J, Montes M, et al. . Antimicrobial susceptibility-guided therapy versus empirical concomitant therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in a region with high rate of clarithromycin resistance. Helicobacter 2016;21:29–34. 10.1111/hel.12231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jenkins H, Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, et al. . Randomised clinical trial: safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of repeated doses of TAK-438 (vonoprazan), a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:636–48. 10.1111/apt.13121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murakami K, Sakurai Y, Shiino M, et al. . Vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, as a component of first-line and second-line triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a phase III, randomised, double-blind study. Gut 2016;65:1439–46. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kusano C, Gotoda T, Suzuki S, et al. . Safety of first-line triple therapy with a potassium-competitive acid blocker for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children. J Gastroenterol 2018;53:718–24. 10.1007/s00535-017-1406-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Savoldi A, Carrara E, Graham DY, et al. . Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori: a systematic review and meta-analysis in World Health Organization Regions. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1372–82. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arslan N, Yılmaz Özlem, Demiray-Gürbüz E. Importance of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for the management of eradication in Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:2854–69. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i16.2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koizumi W, Tanabe S, Hibi K, et al. . A prospective randomized study of amoxycillin and omeprazole with and without metronidazole in the eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;13:301–4. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.01559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cottrill MR, McKinnon C, Mason I, et al. . Two omeprazole-based Helicobacter pylori eradication regimens for the treatment of duodenal ulcer disease in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:919–27. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong BC, Xiao SD, Hu FL, et al. . Comparison of lansoprazole-based triple and dual therapy for treatment of Helicobacter pylori-related duodenal ulcer: an Asian multicentre double-blind randomized placebo controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:217–24. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwartz H, Krause R, Sahba B, et al. . Triple versus dual therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori and preventing ulcer recurrence: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and/or amoxicillin in different dosing regimens. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:584–90. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.169_b.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang J, Zhang Y, Fan L, et al. . Eradication efficacy of modified dual therapy compared with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as a first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:437–45. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yu L, Luo L, Long X, et al. . High‐dose PPI–amoxicillin dual therapy with or without bismuth for first‐line Helicobacter pylori therapy: a randomized trial. Helicobacter 2019;13:e12596 10.1111/hel.12596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang JC, Lin CJ, Wang HL, et al. . High-dose dual therapy is superior to standard first-line or rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:895–905. 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Furuta T, Yamade M, Kagami T, et al. . Dual therapy with vonoprazan and amoxicillin is as effective as triple therapy with vonoprazan, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Digestion 2019:1–9. 10.1159/000502287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sakurai Y, Shiino M, Okamoto H, et al. . Pharmacokinetics and safety of triple therapy with vonoprazan, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or metronidazole: a phase 1, open-label, randomized, crossover study. Adv Ther 2016;33:1519–35. 10.1007/s12325-016-0374-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sjostrom JE, Larsson H. Factors affecting growth and antibiotic susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori: effect of pH and urea on the survival of a wild-type strain and a urease-deficient mutant. J Med Microbiol 1996;44:425–33. 10.1099/00222615-44-6-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. . Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the who priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:318–27. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, et al. . Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut 2013;62:34–42. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boltin D, Levi Z, Gingold-Belfer R, et al. . Impact of previous exposure to macrolide antibiotics on Helicobacter pylori infection treatment outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:900–6. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Muñoz-Gómez P, Jordán-Castro JA, Abanades-Tercero M, et al. . Macrolide use in the previous years is associated with failure to eradicate Helicobacter pylori with clarithromycin-containing regimens. Helicobacter 2018;23:e12452 10.1111/hel.12452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]