Abstract

Brazilian native fruits are a rich source of polyphenolic compounds that can act as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Here, we determined the polyphenolic composition, anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, antioxidant activity and systemic toxicity in Galleria mellonella larvae of Eugenia selloi B.D.Jacks. (synonym Eugenia neonitida Sobral) extract (Ese) and its polyphenol-rich fraction (F3) obtained through bioassay-guided fractionation. Phenolic compounds present in Ese and F3 were identified by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS. The anti-inflammatory activity of Ese and F3 was tested in vitro and in vivo through NF-κB activation, cytokine release and neutrophil migration assays. The samples were tested for their effects against reactive species (ROO•, O2•-, HOCl and NO•) and for their toxicity in Galleria mellonella larvae model. The presence of hydroxybenzoic acid, ellagitannins and flavonoids was identified. Ese and F3 reduced NF-κB activation, cytokine release and neutrophil migration, with F3 being three-fold more potent. Overall, F3 exhibited strong antioxidant effects against biologically relevant radicals, and neither Ese nor F3 were toxic to G. mellonella larvae. In conclusion, Ese and F3 revealed the presence of phenolic compounds that decreased the inflammatory parameters evaluated and inhibited reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. E. selloi is a novel source of bioactive compounds that may provide benefits for human health.

Introduction

The Brazilian Atlantic rainforest is a rich ecosystem which has been extensively threatened by deforestation. With only 12% of the original area left, it shelters numerous fauna and flora species, including approximately 50% endemic edible fruit trees. Occurring in the Atlantic rainforest, Brazilian native fruit species are part of a yet unknown, neglected and underutilized biodiversity, especially for bioprospecting novel molecules with biological properties [1,2].

The genus Eugenia (Myrtaceae family) has approximately 400 native species occurring in the Atlantic rainforest. Brazilian native species have great economical potential for fresh fruit consumption; production of juice, jam and ice cream; as well as for pharmaceutical and nutritional use [2]. Recent studies reported that Eugenia spp. have anti-cancer (E. uniflora and E. brasiliensis), anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (E. leitonii, E. brasiliensis, E. stipitata, E. myrcianthes and E. involucrata), among others [2–5]. Currently, some traditional fruits and Brazilian native fruit species, such as E. uniflora and Euterpe oleracea, have been termed “superfruits” due to their high levels of phytonutrients (bioactive molecules) that can improve regular consumers’ health [6].

Eugenia fruit species contain a rich nutritional value (minerals and vitamins) and are a promising source of phytonutrients, such as carotenoids, flavanols (catechin, epicatechin), anthocyanidins (cyaniding, delphinidin, malvidin), flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), phenolic acids (gallic acid), and others [2–6]. Scientific evidence suggests that regular intake of bioactive molecules contained in native fruits has been associated with a reduced risk of developing oxidative stress-related diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disorders, cancer, arthritis, chronic inflammatory diseases etc [2–9]. The latter commonly go unnoticed and are triggered by oxidative stress generated by reactive oxygen / nitrogen species (ROS / RNS), resulting in cell damage and tissue injury [9]. ROS and RNS can overly activate an important signaling pathway associated with inflammation, the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and thereby they render the inflammatory process more destructive than resolutive [4,9,10]. Thus, the search for, and application of, novel bioactive compounds able to control the inflammatory process while modulating ROS/RNS generation is much needed.

Recently, our research group reported the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of five Brazilian native fruit species [4]. Eugenia selloi B.D.Jacks. (synonym Eugenia neonitida Sobral), showed the strongest in vivo anti-inflammatory activity in mice model and thus was selected for further analysis in the present study. E. selloi, popularly known as “pitangatuba”, “pitangola”, “pitangão” or “pitanga-amarela”, is a shrub tree approximately two meters high, with dark green leaves. Its fruit is 4 cm long and 3 cm wide, has pleasant bittersweet taste with juicy pulp to consume in natura or in beverages, juices and jams [11]. While E. selloi has been used in folk medicine to treat skin depigmentation and vitiligo–because it contains a photosensitizing substance [11], its anti-inflammatory activity, ROS/RNS scavenging activity, and phytochemical composition, remain to be determined.

Thus, our study hypothesis was that the phytochemical compounds present in E. selloi have ROS/RNS scavenging effects and, consequently, inhibit important pro-inflammatory biomarkers. To test our hypothesis, we determined the phytochemical composition of E. selloi extract (Ese) and its polyphenol-rich fraction (F3) and tested them for their anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, antioxidant activity and systemic toxicity in vivo.

Material and methods

Reagents

The reagents were purchased from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA, USA): LC-18 SPE cartridges 2g. Tedia (Fairfield, OH, USA): formic acid. R&D Systems, Inc: TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 kits. Applied Biological Materials Inc. (Richmond, BC,Canada): RAW 264.7 macrophages transfected with the NF-κB-pLUC gene. J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA): acetonitrile, methanol and ethanol. Millipore Milli-Q System (Millipore SAS, Molsheim, France): purified water. Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA): RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640 medium, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 0111:B4, DMSO (dimethylsulfoxide), carrageenan, dexamethasone, diaminofluorescein-2 (DAF-2), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), (±)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), sodium nitroprusside, sodium hypochlorite solution (NaOCl), nitrotetrazolium blue chloride (NBT), dibasic potassium phosphate, 2,2-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), phenazine methosulfate (PMS), rhodamine 123, dihydrochloride (AAPH) and fluorescein sodium salt. Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA): fetal bovine serum. MERCK KGaA (Frankfurt, Germany): Silicagel 60 (0,063–0,200 mm). Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA): luciferin. Amresco, Inc. (West Chester, Pensilvania, EUA): Lysis buffer TNT, mixture of TRIS BASE and Tween 20.

Plant material and extract preparation

Access to E. selloi fruit was previously granted by the Council for Genetic Heritage Management (Brazilian Ministry of Environment; CGEN #AD4B64F). E. selloi B.D.Jacks. samples were collected several times in a farm named “Rare Fruits” (“Frutas Raras” in Portuguese), located in the city of Campina do Monte Alegre, São Paulo, Southeastern Brazil. The farm is in the Atlantic rainforest subtropical region (Cfb—Köppen climate classification), with an altitude of 612 meters (S 23° 53’ 57.06"; W 48° 51’ 24.68"). Fruit samples were collected from November 2015 to February 2016, and the specimen was identified by experts from the herbarium of the “Luiz de Queiroz” College of Agriculture, University of São Paulo (ESALQ/USP), Piracicaba, São Paulo, under voucher HPL 5279. Only intact (undamaged) fruit samples were collected, which were transported under refrigeration and subsequently washed with water. Fruit pulps were separated, frozen, lyophilized, and stored at -18°C until further analysis. For extract preparation, lyophilized E. selloi pulp (50 g) was mixed with ethanol and water (80:20, v/v; respectively). The mixture was submitted to three ultrasound cycles (30 min each), filtered to separate the liquid content, evaporated and lyophilized. E. selloi extract (Ese) was stored at -20°C until further use.

E. selloi extract fractionation

Ese was submitted to a fractionation system by means of an open dry column chromatography using normal phase silica gel. To recover fractions with different polarities, the mixture of ethyl acetate:methanol:water (77:13:10, v/v) was applied onto the top of the column. After the solvent passed through the whole column, six fractions were recovered, evaporated and lyophilized. The fractions were monitored using Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC). Fluorescent compounds were visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light at 366 nm wavelength. Ese and its most active fraction (F3) were submitted to LC-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis.

Phytochemical analysis

Sugar removal

To remove the sugar content of Ese, 500 mg of the extract was diluted with 5 mL of water and centrifuged (5000 x g for 15 min). The precipitate was dissolved in 5 mL of HCl solution (pH = 2.0) and filtered. In parallel, LC-18 SPE cartridges were conditioned with acidic water and methanol (pH = 2.0). Then, 5 mL of Ese diluted in HCl solution were added to each cartridge until the total liquid content passed through the column. The wash process was repeated with acidic water to remove the sugar content. Finally, the compounds of interest were eluted with methanol, and sugar-free Ese was recovered and stored at -20°C until further use.

High-resolution mass spectrometry analysis (LC-ESI-QTOF-MS)

LC-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis was carried out using a chromatograph (Shimadzu Co., Tokyo) with a quaternary pump LC-30AD, photodiode array detector (PDA) SPD-20A. Reversed phase chromatography was performed using Phenomenex Luna C18 column (4.6 x 250 mm x 5 μm). High-resolution mass spectrometry MAXIS 3G –Bruker Daltonics (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) was fitted with a Z-electrospray (ESI) interface operating in negative ion mode with a nominal resolution of 60,000 m/z. Twenty microliters of Ese and F3 were injected into a liquid chromatography system. The conditions for the analysis of Ese were as follows: nebulizer at 2 Bar; dry gas at 8 L/min; temperature at 200 °C and HV at 4500 V. The mobile phase consisted of two solvents: (A) water/formic acid (99.75/0.25, v/v) and (B) acetonitrile/formic acid/water (80/0.25/19.75, v/v). The flow rate was 1 mL/min, and the gradient was initiated with 10% B, increasing to 20% B (10 min), 30% B (20 min), 50% B (30 min), 90% B (38 min), and decreasing to 10% B (45 min), completing after 55 min. The conditions for the analysis of F3 was similar to those of Ese, except for the mobile phase, which consisted of two solvents: water/formic acid (99.75/0.25, v/v) (A) and acetonitrile (100) (B). The flow rate was 1 mL/min, and the gradient was initiated with 10% solvent B, increasing to 30% B (20 min), 50% B (32 min), 95% B (38 min), 95% B (60 min), and decreasing to 10% B (75 min), completing after 80 min. External calibration was carried out using the software MAXIS 3G –Bruker Daltonics 4.3 to check for mass precision and data analysis. The identification of compounds was performed tentatively by comparison of exact mass, MS/MS mass spectra and molecular formulae available from the scientific literature.

Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity

Cell culture and viability in vitro assay

RAW 264.7 macrophages (ATCC® TIB-71™) transfected with the NF-κB-pLUC gene to express luciferase were cultured in endotoxin-free RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%, v/v), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/mL) and L-glutamine (37 °C, 5% CO2). Macrophages were cultured in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells/mL) and incubated overnight. Ese (10, 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μg /mL) and F3 (0.1, 10, 30, 100 and 300 μg /mL), or culture media (negative control), were added to each well and incubated for 24 h. All groups were stimulated with 10 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS), except the negative control. After this period, the supernatant was removed and an MTT solution (0.3 mg/mL) was added to the wells. The plates remained incubated for 3 h (37 °C, 5% CO2). The supernatant was removed and DMSO was added. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA microplate reader.

NF-κB activation, and TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 levels

Macrophage cells transfected were cultured in 24-well plates (3 × 105 cells/mL). The cells were treated with Ese or F3 at 30, 100 and 300 μg/mL for 30 min before LPS stimulation (10 ng/mL) for 4 h, except the culture media control (negative control). After 4 h, cell lysis buffer and 25 μL of luciferase reagent (luciferin at 0.5 mg/mL) were added to each well. Luminescence was measured using a white microplate reader (SpectraMax M3, Molecular Devices). In addition, TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 levels were determined according to the protocols provided by the manufacturers on an ELISA microplate reader. The results were expressed as pg/mL.

In vivo anti-inflammatory assays

Animals

In vivo experiments were performed with male SPF (specific-pathogen free) C57BL/6JUnib mice, purchased from CEMIB / UNICAMP (Multidisciplinary Center for Biological Research, SP, Brazil), weighing between 22 and 25 g. All animals were housed in vivarium under humidity (40–60%) and temperature (22 ± 2 °C) control in 12 h light-dark cycle, with access to food and water ad libitum. For the experiment, all animals were deprived of food for 8 h before oral administration. This study complied with the National Council for Animal Experimentation Control guidelines for the care and use of animals in scientific experimentation (https://www.mctic.gov.br/mctic/opencms/institucional/concea/paginas/legislacao.html), according to the Brazilian Law 11,794, of October 8, 2008. All animals were euthanized by deepening anesthesia with Ketamine and Xylazine (300 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg, respectively) and, after, submitted to cervical dislocation. The study protocol was previously approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on Animal Research at the University of Campinas (CEUA/UNICAMP, Protocol Number 4371–1, approved on 09/23/2016).

Inhibition of neutrophil migration

Mice received orally (via gavage) single doses of Ese (3 or 10 mg/kg) or F3 (3 or 10 mg/kg). The negative control group received oral administration of 0.9% saline (vehicle) and 2 mg/kg dexamethasone. After 1 h, all animals received an inflammatory challenge by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of the flogistic agent carrageenan (500 μg/cavity) for 4 h, except the vehicle group. Next, the animals were sacrificed, their peritoneal cavities were washed and recovered to count for the total number of leukocytes and neutrophils. The results were expressed as number of neutrophils per cavity. TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 levels were determined using an ELISA microplate reader. The results were expressed as pg/mL.

Evaluation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species scavenging capacity (antioxidant activity)

Peroxyl radical (ROO•)

Briefly, 30 μL of Ese or F3 plus 60 μL of fluorescein and 110 μL of an AAPH solution were transferred to a microplate. The reaction was performed at 37 °C and absorbance was measured every minute for 2 h at 485 nm (excitation) and 528 nm (emission) on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Trolox standard was used at concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 400 μM. The results were expressed as μmol/Trolox equivalents per g of extract/fraction (Ese and F3) [4].

Superoxide anion (O2•-)

The capacity of Ese and F3 to scavenge O2•- generated by the NADH/PMS system was determined as previously described [12]. Briefly, 100 μL of NADH, 50 μL of NBT, 100 μL of Ese or F3 (at different concentrations) and 50 μL of PMS were mixed in the microplate. The assay was performed at 25 °C and absorbance was measured after 5 min at 560 nm. A control was prepared replacing the sample with the buffer, and a blank was prepared for each sample dilution replacing PMS and NADH with the buffer. Absorbance was measured in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and the results were expressed as IC50, the mean concentration (μg/mL) of Ese or F3 required to quench 50% of the superoxide radicals [12].

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl)

The HOCl scavenging activity of Ese and F3 was measured by monitoring their effects on HOCl-induced oxidation of dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR) to rhodamine 123, with modifications. HOCl was prepared using a 1% NaOCl solution, adjusting the pH to 6.2. The reaction mixture contained Ese or F3 at different concentrations, phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), DHR, and HOCl, in a final volume of 300 μL. The assay was carried out at 37 °C in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and fluorescence was measured immediately at 528 ± 20 nm (emission) and 485 ± 20 nm (excitation). The results were expressed as IC50 (μg/mL) of Ese or F3 [4].

Nitric oxide (NO•)

The nitric oxide (NO•) activity of Ese and F3 was determined using diaminofluorescein-2 (DAF-2) as a NO• probe. Briefly, 50 μL of Ese or F3 plus 50 μL of SNP solution, 50 μL of buffer and 50 μL of DAF solution were added to the wells (96-well plate). Changes in fluorescence (excitation = 495 nm, emission = 515 nm) were measured in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) over a 120-min period at 5-min intervals. The results were expressed as IC50 (μg/mL) of Ese or F3 [4].

Systemic toxicity

Galleria mellonella model

To provide preliminary evidence on the potential toxic effects of Ese and F3, their acute systemic toxicity was determined in a G. mellonella L. model. G. mellonella larvae were kindly provided by L. G. Leite from the Biological Institute, Department of Agriculture and Supply (Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil). The larvae were maintained at 37°C in a BOD incubator until use. Six equal increasing doses of Ese and F3 (0.01, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 g/kg) were tested. Larvae with no signs of melanization, weighing 200 to 300 mg, were randomly selected for each group (n = 15). An aliquot of 10 μL of Ese, F3 or control (0.9% NaCl, w/v) were injected into their hemocoel via the last left proleg using a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV). The larvae were incubated at 30 °C and their survival was monitored at selected intervals for up to 72 h. Larvae with no movements upon touch were counted as dead [13].

Statistical analysis

The data were checked for normality and submitted to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). In in vivo toxicity assays, survival curves of treated and untreated G. mellonela larvae were compared using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The results were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Phytochemical analysis

The phenolic compounds were tentatively identified by analysis of their exact masses, MS/MS spectra and molecular formulas using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry analysis (LC-ESI-QTOF-MS). As seen in Table 1, the chemical analysis revealed 16 compounds in Ese, 13 compounds in F3, and 8 compounds present in both samples. Overall, hydroxybenzoic acid, flavanols, ellagitannins, flavone and flavonols were detected in the samples. The chemical fractionation process is shown in supporting information S1 Fig. Visual aspect of Ese, chemical fractionation, yield and thin layer chromatography.

Table 1. Chemical analysis of Ese and F3 by High-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-QTOF-MS).

| Compound | Rt (min) | Molecular formula | [M-H]- | MS fragments (m/z) | Ese | F3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxybenzoic acid | ||||||

| Gallic acid | 4.6 | C7H6O5 | 169.0105 | 125.0209, 117.9917, 140.5531, 150.3022 | - | + |

| Syringic acid hexoside | 14.7 | C15H20O10 | 359.1259 | 153.0888, 197.0771, 212,6754, 119.0322 | + | + |

| Sinapic acid-O-hexoside I | 19.9 | C17H22O10 | 385.1409 | 179.1035, 119.0319, 135,1143, 223.0879 | + | + |

| Sinapic acid-O-hexoside II | 20.1 | C17H22O10 | 385.1409 | 179.1044, 135.1152, 113.0207, 223.0874 | - | + |

| Flavanols | ||||||

| (Epi)catechin | 11.4 | C15H14O6 | 289.0726 | 289.0726, 245.0814, 179.0340, 205.0473 | + | - |

| (Epi)catechin derivative | 12.8 | C15H14O6 | 401.0886 | 289.0725, 245.0825, 205.0508, 179.0342 | + | - |

| Ellagitannins | ||||||

| Ellagic acid | 20.2 | C14C6O8 | 300.9990 | 300.9999, 229.5014, 255.2311, 257.0124 | + | - |

| Galloyl-HHDP-hexoside | 8.3 | C27H22O18 | 633.0559 | 300.9922, 301.9946, 169.0092, 463.0512, 481.0551 | - | + |

| Di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose derivate I | 10.9 | C41H27O26 | 467.0369 [M − 2H]2- | 275.0200, 343.0106, 300.9988,169.0503 | + | + |

| Di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose I | 10.9 | C41H27O26 | 935.0797 | 299.0203, 275.0199, 300.9994, 633.0743 | + | - |

| Di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose derivate II | 11.8 | C41H27O26 | 467.0372 [M − 2H]2- | 275.0200, 169.0146, 301.000, 343.0100 | + | - |

| Di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose II | 11.8 | C41H27O26 | 935.0806 | 275.0200, 299.0206, 633.0737, 300.99898 | + | - |

| Di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose derivate III | 16.6 | C41H27O26 | 467.0365 [M − 2H]2- | 300.9996, 423.1872, 169.0141, 275.0247 | + | - |

| Flavone | ||||||

| Apigenin-7-O-glucoside | 14.0 | C21H20O11 | 431.1810 | 205.1177, 121.0290, 119.0320, 269.2089, 153.0176, 241.9622, 311.4209 | - | + |

| Flavonols | ||||||

| Quercetin-O-hexoside I | 20.2 | C21H20O12 | 463.0887 | 301.0328,271.02445,463.0884, 243.0800 | + | + |

| Quercetin-O-hexoside II | 20.5 | C21H20O12 | 463.0890 | 301.0352, 271.0248, 243.0802, 463.0889 | + | + |

| Quercetin-O-(O-galloyl)-hexoside | 21.2 | C28H24O16 | 615.0996 | 301.0357, 271.0248, 179.0982, 151.0039 | + | + |

| Quercetin-O-acethylhexoside | 22.4 | C23H22O13 | 505.0994 | 221.0238, 301.0335, 506.1011, 463.0024 | + | - |

| Quercetin-3-malonylglucoside | 22.4 | C24H22O15 | 549.0889 | 300.0279, 301.0328, 271.0249, 243.0807 | + | + |

| Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 23.2 | C21H20O11 | 447.0940 | 285.0335, 284.0335, 255.0299, 227.0851 | + | + |

Bold values indicate the main fragments; Rt = retention time; [M-H]- (negative ionization mode) experimental mass of compound; + detected/—not detected.

In vitro anti-inflammatory assays

Viability assay, NF-κB activation, TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 levels

As seen in Fig 1A, treatment with Ese at concentrations up to 300 μg/mL did not significantly affect cell viability in LPS-stimulated macrophages as compared to the culture media control (P > 0.05). However, cells treated with Ese at 1000 μg/mL showed reduced cell viability (14%) as compared to the control (P < 0.05). As expected, LPS treatment (10 ng/mL) did not affect cell viability (P > 0.05).

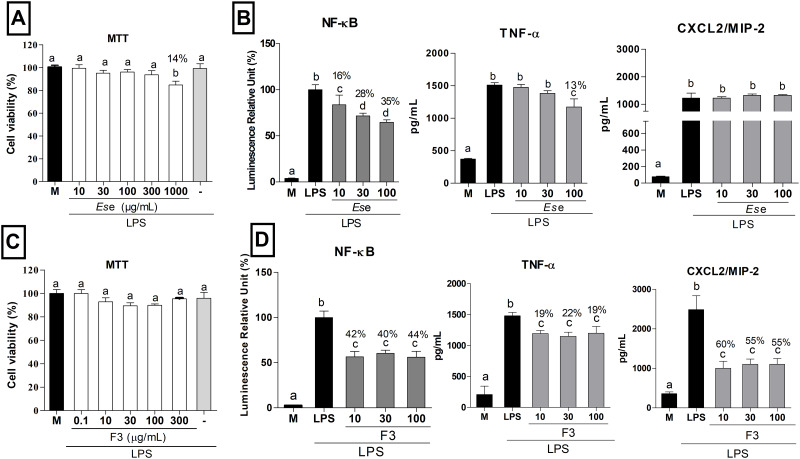

Fig 1. Effects of Ese and F3 on cell viability and inflammation markers in macrophages.

(A and C) Evaluation of RAW 264.7 macrophages treated with culture medium (M), LPS (10 ng/mL,-), Ese (10, 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μg/mL) and F3 (0.1, 10, 30, 100 and 300 μg/mL) for 24h. (B and D) Evaluation of NF-κB activation and TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 release in RAW 264.7 macrophages. The results were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 4. Different letters indicate statistical difference and the symbol % indicates a decrease in NF- kB activation. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, P < 0.05.

Fig 1B shows that treatment with Ese (10, 30 and 100 μg/mL) significantly reduced NF-κB activation by 16%, 28% and 35%, respectively, as compared to LPS-treated cells. Moreover, treatment with Ese reduced TNF-α levels by 13% at 100 μg/mL (P < 0.05), but no significant differences were observed at the concentrations of 10 and 30 μg/mL (P > 0.05). Likewise, treatment with Ese did not affect the release of CXCL2/MIP-2 by macrophages at any tested concentration as compared to LPS-treated cells (P > 0.05, Fig 1B). The polyphenol-rich fraction (F3) from Ese did not affect macrophage viability at any tested concentration as compared to the culture media control and LPS-treated cells (P > 0.05; Fig 1C). Macrophage cells treated with F3 at 10, 30 and 100 μg/mL had NF-κB activation significantly reduced (42%, 40% and 44%, respectively) as compared to LPS-treated cells (P < 0.05; Fig 1D). At 10, 30 and 100 μg/mL, F3 reduced (19%, 22% and 19%, respectively) the release of TNF-α compared to the control (P < 0.05). Finally, at 10, 30 and 100 μg/mL, F3 reduced (60%, 55% and 55%, respectively) CXCL2/MIP-2 levels compared to the control (P < 0.05; Fig 1D). The difference between CXCL2/MIP-2 levels in Fig 1B and 1D is due to biological variability, and the axis Y was normalized to 2400 pg/mL.

The screening of all fractions through MTT viability and NF-κB activation assays is shown in supporting information S2 Fig (Cytotoxicity and NF-κB activation of the polyphenol-fraction from Ese in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells).

In vivo anti-inflammatory assays

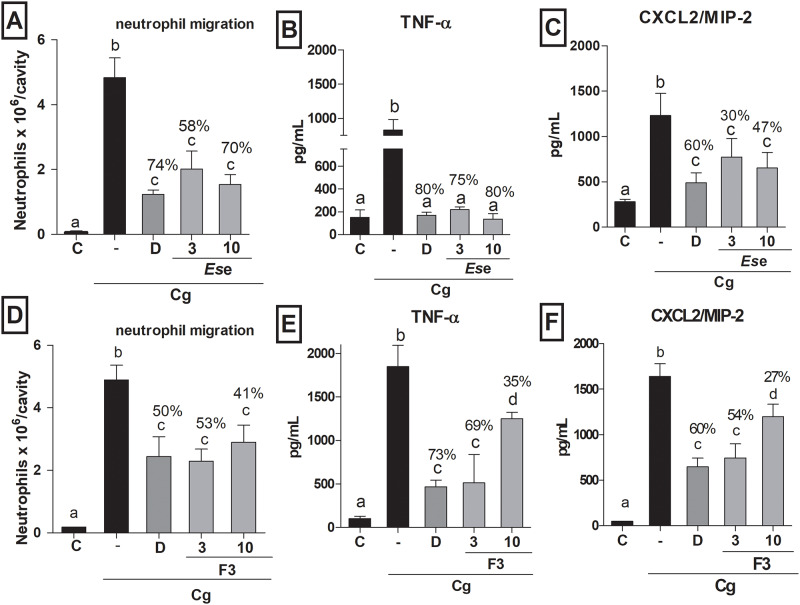

The inhibitory effects of Ese and F3 on neutrophil influx were determined in vivo. Mice pre-treated with Ese at 3 and 10 mg/kg showed a significant decrease in neutrophil influx (58% and 70%, respectively) as compared to those treated with the control carrageenan (Fig 2A). As expected, mice that received dexamethasone showed a significant decrease in neutrophil migration (74%). Interestingly, there was no statistical difference in terms of neutrophil influx between mice treated with Ese (at both doses) and those treated with the positive control dexamethasone, a gold-standard corticosteroid widely used in medicine and dentistry (P > 0.05). Treatment with Ese at 3 and 10 mg/kg also reduced the release of TNF-α (75% and 80%, respectively) and CXCL2/MIP-2 (30% and 47%, respectively) into the peritoneal cavity of mice as compared to each control group, Fig 2B and 2C, respectively.

Fig 2. Effects of Ese and F3 on neutrophil migration and cytokine release in vivo.

(A and D) Effects of vehicle (C), carrageenan (-), dexamethasone (D; 2 mg/kg), Ese or F3 (3 and 10 mg/kg) on neutrophil migration into the peritoneal cavity of mice induced by i.p. administration of carrageenan (500 μg/cavity, -). (B and E) Effects of the treatments on the release of TNF-α (1.5 h) in mice. (C and F) Effects of the treatments on the release of CXCL2/MIP-2 (3 h) in mice. The results were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 5–6. Different letters indicate statistical difference and all groups were compared to each other. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test, P < 0.05.

Mice treated with F3 at 3 and 10 mg/kg showed reduced neutrophil migration (53% and 41%, respectively) in relation to the control group (P < 0.05; Fig 2D). In our study, the positive control dexamethasone reduced neutrophil migration by 50% (P < 0.05). Mice treated with F3 (3 and 10 mg/kg) showed reduced levels of TNF-α (69% and 35%, respectively) and CXCL2/MIP-2 (54% and 27%, respectively) when compared to the control group (P < 0.05; Fig 2E and 2F, respectively). Given the anti-inflammatory potential of Ese and F3, both samples were further tested for their antioxidant activity (ROS / RNS scavenging capacity).

Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species

Ese and F3 were tested for their antioxidant activity against peroxyl radical (ROO•), superoxide anion (O2•-), hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and nitric oxide (NO•). We investigated the antioxidant activity of Ese and F3 against reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, which are biologically equivalent to the human metabolism. As seen in Table 2, while Ese was the most active sample to deactivate superoxide anion O2•- (172 μg/mL), F3 showed the highest capacity to quench peroxyl radical (680 μmol TE/g extract), hypochlorous acid HOCl (1.13 μg/mL) and nitric oxide NO• (5.05 μg/mL) as compared to Ese. The results for the radicals O2•-, HOCl and NO• are expressed as IC50—which means the amount of substance required to deactivate 50% of the radicals. Overall, F3 seems to have a greater concentration of compounds with both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

Table 2. Antioxidant activity of Ese and F3 against peroxyl radical (ROO•), superoxide anion (O2•-), hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and nitric oxide (NO•).

| Sample | ROO• μmol TE/g extract | O2•- μg/mL | HOCl μg/mL | NO•μg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ese | 250 ± 0.008a | 172.00 ± 14.90a | 16.68 ± 1.17a | 11.48 ± 1.84a |

| F3 | 680 ± 0.02b | 849.00 ± 4.04b | 1.13 ± 0.15b | 5.05 ± 1.07b |

ROO• is expressed as μm TE/mg of extract (TE = Trolox equivalent), O2•-, HOCl and NO• are expressed as IC50 (μg/mL). The results were expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation), n = 3. Different letters in the same column indicate statistical difference (P < 0.05), according to Student’s t test.

Toxicity of Ese and F3 in G. mellonella model

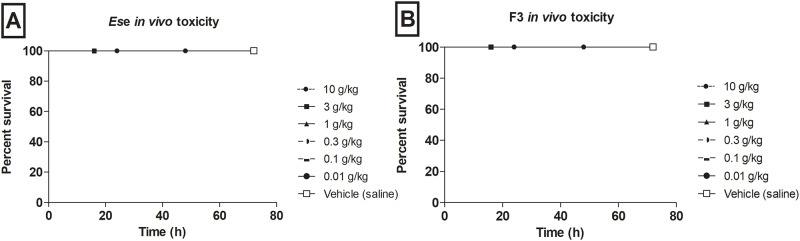

G. mellonella larvae were injected increasing doses of Ese and F3 and had their survival monitored for 72 h. As seen in Fig 3, larvae treated systemically with Ese and F3 did not demonstrate toxic effects at any tested dose (P > 0.05), indicating negligible toxicity of the samples in this in vivo model.

Fig 3. Systemic toxicity of Ese and F3 in G. mellonella larvae model.

Larvae were treated with Ese and F3 at 0.01, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 g/kg or vehicle (saline) and had their survival monitored up to 72 h (P > 0.05, Log-rank test).

Discussion

It is estimated that approximately 1.7 million deaths per year are related to the low intake of fruits and vegetables, despite the wide cultivation of fruits worldwide. A minimum daily intake of 400 g is required for prevention of chronic diseases and several micronutrient deficiencies [14]. Brazilian native fruit species can be an important ally to one’s health as functional foods while fostering agribusiness and protecting deforestation in threatened rainforests and biomes.

In this bioguided study, we demonstrated that E. selloi extract and its polyphenol-rich fraction (F3) have (i) anti-inflammatory and (ii) antioxidant activity and (iii) low toxicity in vivo. Ese and F3 samples were submitted to chemical analysis for tentative identification of compounds based on exact masses, MS/MS spectra and molecular formulas. Gallic acid (m/z 169.0105), identified in F3, is an ion produced at m/z 125 due to loss of a CO2 [15]. Another compound presented a pseudomolecular ion [M-H]− at m/z 359.1259, yielding MS2 fragments at m/z 197 (loss of a hexosyl moiety; [syringic acid-H]−) and 153 (base peak; [syringic acid-H-CO2]−), suggesting that it could be a syringic acid hexoside in Ese and F3 [16]. The fragments corresponding to m/z 385.1409 were tentatively identified as isomers of sinapic acid-O-hexoside [17].

(Epi)catechin (m/z 289.0726) (flavanol class) and (epi)catechin derivative (m/z 401.0886) were also found in Ese, but not in F3. These compounds are stereoisomers characterized by the molecular ion [M-H- 289]-. The fragments of MS2 corresponding to m/z 245, m/z 205 and m/z 179 indicate that the compound is (epi)catechin [12,18]. The ion m/z 245 may result from a loss of a CO2 group [M-H-44]- by decarboxylation or by CH2CHOH- group loss [15].

Ellagic acid (m/z 300.9990), which was detected in Ese, belongs to the class of organic compounds known as ellagitannin. This compound is well known for its antioxidant activity with free radical scavenging properties [19]. Ellagitannin compounds were found in both samples, although galloyl-HHDP-hexoside (m/z 633.0559) was detected only in F3. Two di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose (m/z 935) isomers and three di-HHDP-galloyl-glucose derivate (m/z 467 [M-2H]-2) isomers were identified in Ese and F3, which presented the fragments m/z 633 (M-HHHDP) and m/z 301 (ellagic acid) [18,20,21]. Apigenin-7-O-glucoside (m/z 431.1810) was detected only in F3 based on the m/z 269 fragment, which is typical of apigenin [22].

The following flavonols were identified in Ese and F3: quercetin-O-hexoside (m/z 463); quercetin-O-(O-galloyl)-hexoside (m/z 615.0996), which produced m/z 179 and 151 corresponding a quercetin fragmentation pattern; quercetin-3-malonylglucoside (m/z 549.0889), which presented the m/z 301 fragment, a typical ion following the loss of a hexose molecule [M-H-162]- [4,23,24]. Finally, the kaempferol-3-O-glucoside (m/z 447.0940) was identified in Ese and F3 composition [25].

The compound quercetin-O-acethylhexoside, present only in Ese, was tentatively identified as quercetin-acylated-hexoside based on literature data. This compound showed m/z 505.0994 with fragmentation at m/z 463 due to loss of an acetyl group (42 Da) and m/z at 301 due to loss of a hexoside residue (162 Da) [26].

It is worth noting that some compounds were present in F3, but not in Ese. This can be explained by the fact that F3 was obtained through a fractionation process, that is, chemical purification, in a way that compounds previously undetectable become more concentrated and therefore detectable by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS.

Once Ese and F3 were chemically characterized, we next tested both samples for their anti-inflammatory activity in different models. Inflammation is an orchestrated host response involving different cell types, such as macrophages. The inflammatory response leads to an intracellular increase of ROS and RNS by macrophages, which can activate the NF-κB intracellular pathway [27,28]. Once activated, this nuclear factor initiates a series of cascade reactions resulting in translocation of p65 and p50 dimers to the macrophage nucleus and ultimately induce gene transcription and release of inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 [27,28]. Subsequently, inflammatory mediators increase protein expression on the surface of endothelial cells (selectins and integrins) that control the neutrophil flow into the inflammatory focus [4].

In our study, Ese and F3 reduced NF-κB activation in macrophages, decreased the release of TNF-α and CXCL2/MIP-2 and, consequently, mitigated neutrophil migration in mice. Some chemical compounds as ellagitannin identified in Ese and F3, have been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation and to modulate neutrophil influx during inflammation [13,21,29]. Quercetin and kaempferol are known to reduce NF-κB activation, TNF-α and IL-1β release, as well as to decrease leukocyte recruitment and oxidative stress [5,13,30–32].

Our findings show that Ese and F3 modulated neutrophil migration into the inflammatory focus. Although Ese is a chemically crude extract, a complex mixture of bioactive compounds at low concentration, its inhibitory activity on neutrophil influx did not differ from that of the gold standard dexamethasone, which is a pure monodrug. These findings illustrate the potential of E. selloi as a functional food to reduce or prevent inflammatory diseases and promote health.

In two similar studies, the extracts of E. leitonii seeds and E. brasiliensis pulp (also from the Eugenia genus) reduced neutrophil influx into the inflammatory focus, with no difference from dexamethasone, and also decreased NF-κB activation [533]. Interestingly, these three species (E. leitonii, E. brasiliensis and E. selloi) share two compounds in their chemical composition, ellagic acid and quercetin, which may be responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity observed [33,34].

Despite the benefits of the inflammatory response, an exacerbated presence of neutrophils and other cells generating excessive ROS / RNS production may create an imbalance in pro- and antioxidants, ultimately damaging tissues, DNA, proteins, and other host components [35].

Here, Ese and F3 were further tested for their ROS / RNS scavenging activity. Our findings indicate that F3 was more effective than Ese in this regard, despite the fact that the fractionation process was guided by the anti-inflammatory data. Ese was more effective in quenching the superoxide anion (O2•) compared to F3, which can be explained by the synergism among the phenolic compounds present in the crude extract. Four Eugenia spp. were previously tested for their O2• radical scavenging activity and the authors reported IC50 ranging from 215 to 402 μg/mL, indicating that E. selloi is more potent than those native species. [5]. The superoxide anion contributes to metabolic oxidative stress, resulting in cell damage and genomic instability. Hence, the inhibition of this radical can be an important strategy to prevent diseases related to oxidative stress [35].

The ORAC (oxygen radical absorbance capacity) assay is a direct method to measure hydrophilic and lipophilic chain-breaking antioxidant capacity against the peroxyl radical, generated by AAPH via hydrogen atom transfer reactions [35]. In the context of inflammation, ROS present in the lipid tissue are converted into peroxyl radical and may cause cell membrane damage, neoplasia and, most likely, several inflammatory chronic and degenerative diseases [35,36]. Our findings showed that the peroxyl radical scavenging capacity of F3 was three-fold greater than that of Ese. A previous study testing gallic acid showed ORAC values of 7.88 mol TE/g, which is 32-fold and 12-fold more potent than that of Ese and F3, respectively [37]. Here, isomers of quercetin were identified in both samples and were previously shown to have antioxidant activity against peroxyl radical [38]. The potent peroxyl radical scavenging capacity of Ese and F3 might be due to the chemical compounds present in their composition, such as hydroxybenzoic acid and flavonols.

We next determined the ROS (hypochlorous acid—HOCl) scavenging activity of the samples. Ese and F3 exhibited different IC50 values, which indicated that F3 was approximately 16-fold more potent than Ese to scavenge HOCl. Although Ese is a crude extract, its HOCl radical scavenging activity was comparable to that of Trolox (IC50 of 134 μg/mL), a standard drug [39]. As compared to other native fruits, Ese and F3 were more active than E. brasiliensis and E. leitonii pulp (IC50 of 42 and 109 μg/mL, respectively) [5].

The samples were further tested for their nitric oxide (NO•) scavenging capacity. In this regard, F3 was approximately 2-fold more effective than Ese. A previous study investigated the NO• scavenging capacity of E. stipitata, a Brazilian native fruit belonging to Eugenia genus, and observed an equivalent activity (IC50 of 6.95 μg/mL) [4]. We detected the presence of quercetin derivatives in both samples and this flavonoid is known to be more potent than other antioxidant nutrients, such as vitamin C and vitamin E [40]. In another study, the authors evaluated the NO• scavenging capacity of Monodora myristica extract and observed activity (IC50 of 171.38 μg/mL) and this antioxidant activity could be related with the presence of syringic acid, also identified in Ese and F3 [41].

The different potency observed in the samples can be due to the synergism and chemical composition present in the crude extract and its fraction.

This is the first report on the ROS / RNS scavenging activity E. selloi extract and its purified fraction (F3). ROS and RNS are important components in the inflammation process for their capacity to promote cell / tissue damage in the organism. The question that remains is how and how much ROS and RNS contribute to the inflammatory response. Thus, controlling the balance between oxidation and anti-oxidation through exogenous antioxidants obtained from the diet (e.g., daily fruit intake) is a promising strategy to prevent the onset of inflammatory diseases [10,40].

This is also the first report on the in vivo systemic toxicity of Ese and F3 in G. mellonella larvae. This is a simple, a low-cost, and validated model widely used, because the results obtained in this model correlate with those observed in mammals [42]. In our study, we did not find the lethal dose (LD50) of the samples even when testing a dose 1000 times higher (10 g/kg) than that used in mice (10 mg/kg). In a previous study with other Brazilian native fruit (E. leitonii seed and E. brasiliensis leaf extracts), the authors showed LD50 of 1.5 g/kg for both extracts using G. mellonella model. However, we evaluated the pulp extract in our study, which seems to have negligible toxicity in this model as compared to other parts of Eugenia spp. fruits [13].

Conclusions

E. selloi has proven to be a good source of bioactive compounds, even better than the best fruits traditionally consumed, and it was further shown to modulate the inflammatory process. This study adds value to the promising Brazilian native fruit that have emerged as a source of bioactive compounds providing benefits for human health (functional foods), contributing to the development of agribusiness for many families, and also contributing to preservation of biodiversity, particularly in the Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest.

Supporting information

(TIFF)

(TIFF)

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Helton J. Teodoro Muniz from “Frutas Raras” Farm for providing the Eugenia selloi B.D.Jacks. (pitangatuba) samples used in this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant numbers 2016/02926-6 to JGL and 2017/09898-0 to PLR); the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Grant # 310522/2015-3 to PLR and 307893/2016-2 to SMdA); and part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 to JGL. There was no additional external funding for this study.

References

- 1.Sousa JA, Srbek-Araujo AC. Are we headed towards the defaunation of the last large Atlantic Forest remnants? Poaching activities in one of the largest remnants of the Tabuleiro forests in southeastern Brazil. Environ Monit Assess. 2017; 189:1–13. 10.1007/s10661-017-5854-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Araújo FF, Neri-Numa IA, de Paulo Farias D, da Cunha GRMC, Pastore GM. Wild Brazilian species of Eugenia genera (Myrtaceae) as an innovation hotspot for food and pharmacological purposes. Food Res Int. 2019;121:57–72. 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietrovski EF, Magina MD, Gomig F, Pietrovski CF, Micke GA, Barcellos M, et al. Topical anti-inflammatory activity of Eugenia brasiliensis Lam. (Myrtaceae) leaves. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:479–487. 10.1211/jpp.60.4.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soares JC, Rosalen PL, Lazarini JG, Massarioli AP, da Silva CF, Nani BD, et al. Comprehensive characterization of bioactive phenols from new Brazilian superfruits by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS, and their ROS and RNS scavenging effects and anti-inflammatory activity. Food Chem. 2019;281:178–188. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Infante J, Rosalen PL, Lazarini JG, Franchin M, Alencar SM. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Unexplored Brazilian Native Fruits. PLoS One. 2016; 6;11(4):e0152974 10.1371/journal.pone.0152974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang SK, Alasalvar C, Shahidi F. Superfruits: Phytochemicals, antioxidant efficacies, and health effects—A comprehensive review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.2019;59:1580–1604. 10.1080/10408398.2017.1422111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Souza AM, de Oliveira CF, de Oliveira VB, Betim FCM, Miguel OG, Miguel MD. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Antimicrobial Activities of Eugenia Species—A Review. Planta Med. 2018;84:1232–1248. 10.1055/a-0656-7262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueirôa Ede O, Nascimento da Silva LC, de Melo CM, Neves JK, da Silva NH, Pereira VR, et al. Evaluation of antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and cytotoxic action of fractions from Eugenia uniflora L. and Eugenia malaccensis L.: correlation with polyphenol and flavanoid content. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:125027 10.1155/2013/125027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavecchia T, Rea G, Antonacci A, Giardi MT. Healthy and adverse effects of plant-derived functional metabolites: the need of revealing their content and bioactivity in a complex food matrix. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53:198–213. 10.1080/10408398.2010.520829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1126–1167. 10.1089/ars.2012.5149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negri TC, Berni PRA, Brazaca SGC. Nutritional value of native and exotic fruits of Brazil. Biosaúde. 2016;18:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melo PS, Massarioli AP, Denny C, dos Santos LF, Franchin M, Pereira GE, et al. Winery by-products: extraction optimization, phenolic composition and cytotoxic evaluation to act as a new source of scavenging of reactive oxygen species. Food Chem. 2015;181:160–169. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sardi JC, Freires IA, Lazarini JG, Infante J, de Alencar SM, Rosalen PL. Unexplored endemic fruit species from Brazil: Antibiofilm properties, insights into mode of action, and systemic toxicity of four Eugenia spp. Microb Pathog. 2017;105:280–287. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.02.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO (World Health Organization). Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption around the world [internet], 2017. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/fruit/en/.

- 15.Baskaran R, Pullencheri D, Somasundaram R. Characterization of free, esterified and bound phenolics in custard apple (Annona squamosa L) fruit pulp by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Food Res Int. 2016;82:121–127. Pii: S0963-9969(16)30042. 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barros L, Dueñas M, Pinela J, Carvalho AM, Buelga CS, Ferreira IC. Characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds in four tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) farmers’ varieties in northeastern Portugal homegardens. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2012;67:229–234. 10.1007/s11130-012-0307-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraige K, Dametto AC, Zeraik ML, de Freitas L, Saraiva AC, Medeiros AI, et al. Dereplication by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS and Screening for Biological Activities of Byrsonima Species (Malpighiaceae). Phytochem Anal. 2018;29:196–204. 10.1002/pca.2734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regueiro J, Sánchez-González C, Vallverdú-Queralt A, Simal-Gándara J, Lamuela-Raventós R, Izquierdo-Pulido M. Comprehensive identification of walnut polyphenols by liquid chromatography coupled to linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2014;152:340–348. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell TF, McKenzie J, Murray J, Delgoda R, Bowen-Forbes CS. Rubus rosifolius varieties as antioxidant and potential chemopreventive agents. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;37:49–57. 10.1016/j.jff.2017.07.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grace MH, Warlick CW, Neff SA, Lila MA. Efficient preparative isolation and identification of walnut bioactive components using high-speed counter-current chromatography and LC-ESI-IT-TOF-MS. Food Chem. 2014;158:229–38. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fracassetti D, Costa C, Moulay L, Tomás-Barberán FA. Ellagic acid derivatives, ellagitannins, proanthocyanidins and other phenolics, vitamin C and antioxidant capacity of two powder products from camu-camu fruit (Myrciaria dubia). Food Chem. 2013;139:578–588. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-Las HR, Quifer-Rada P, Andrés A, Lamuela-Raventós R. Polyphenolic profile of persimmon leaves by high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS). J. Funct. Foods. 2016;23:370–377. 10.1016/j.jff.2016.02.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saldanha LL, Vilegas W, Dokkedal AL. Characterization of flavonoids and phenolic acids in Myrcia bella Cambess using FIA-ESI-IT-MS(n) and HPLC-PAD-ESI-IT-MS combined with NMR. Molecules. 2013;18:8402–8416. 10.3390/molecules18078402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aaby K, Grimmer S, Holtung L. Extraction of phenolic compounds from bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) press residue: Effects on phenolic composition and cell proliferation. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2013;54:257–264. 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.05.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelebek H. LC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS characterization of phenolic constituents in Turkish black tea: Effect of infusion time and temperature. Food Chem. 2016;204:227–238. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolniak-Ostek J. Identification and quantification of polyphenolic compounds in ten pear cultivars by UPLC-PDA-Q/TOF-MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016; 49:65–77. 10.1016/j.jfca.2016.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taniguchi K, Karin M. NF-κB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:309–324. 10.1038/nri.2017.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thulasingam S, Massilamany C, Gangaplara A, Dai H, Yarbaeva S, Subramaniam S, et al. miR-27b*, an oxidative stress-responsive microRNA modulates nuclear factor-kB pathway in RAW 264.7 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;352:181–188. 10.1007/s11010-011-0752-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fumagalli M, Sangiovanni E, Vrhovsek U, Piazza S, Colombo E, Gasperotti M, et al. Strawberry tannins inhibit IL-8 secretion in a cell model of gastric inflammation. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:703–712. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chekalina N, Burmak Y, Petrov Y, Borisova Z, Manusha Y, Kazakov Y, et al. Quercetin reduces the transcriptional activity of NF-kB in stable coronary artery disease. Indian Heart J. 2018;70:593–597. 10.1016/j.ihj.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma D, Gondaliya P, Tiwari V, Kalia K. Kaempferol attenuates diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting RhoA/Rho-kinase mediated inflammatory signalling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:1610–1619. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadioglu O, Nass J, Saeed ME, Schuler B, Efferth T. Kaempferol Is an Anti-Inflammatory Compound with Activity towards NF-κB Pathway Proteins. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:2645–2650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazarini JG, Sardi JCO, Franchin M, Nani BD, Freires IA, Infante J, et al. Bioprospection of Eugenia brasiliensis, a Brazilian native fruit, as a source of anti-inflammatory and antibiofilm compounds. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;102:132–139. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lazarini JG, Franchin M, Infante J, Paschoal JAR, Freires IA, Alencar SM, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity and polyphenolic profile of the hydroalcoholic seed extract of Eugenia leitonii, an unexplored Brazilian native fruit. J Funct Foods. 2016;26:249–257. 10.1016/j.jff.2016.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Fattori V, Zarpelon AC, Borghi SM, Staurengo-Ferrari L, Carvalho TT, et al. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits superoxide anion-induced pain and inflammation in the paw skin and spinal cord by targeting NF-κB and oxidative stress. Inflammopharmacology. 2016;24:97–107. 10.1007/s10787-016-0266-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang D, Ou B, Prior RL. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1841–1856. 10.1021/jf030723c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liew SS, Ho WY, Yeap SK, Sharifudin SAB. Phytochemical composition and in vitro antioxidant activities of Citrus sinensis peel extracts. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5331; 1–16. 10.7717/peerj.5331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crascì L, Cardile V, Longhitano G, Nanfitò F, Panico A. Anti-degenerative effect of Apigenin, Luteolin and Quercetin on human keratinocyte and chondrocyte cultures: SAR evaluation. Drug Res (Stuttg). 2018;68:132–138. 10.1055/s-0043-120662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodrigues E, Mariutti LR, Mercadante AZ. Carotenoids and phenolic compounds from Solanum sessiliflorum, an unexploited Amazonian fruit, and their scavenging capacities against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:3022–3029. 10.1021/jf3054214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguirre L, Arias N, Macarulla MT, Gracia A, Portillo MP. Beneficial effects of quercetin on obesity and diabetes. Open Nutraceuticals J. 2011;4:189–198. 10.2174/1876396001104010189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moukette BM, Pieme CA, Njimou JR, Biapa CP, Marco B, Ngogang JY. In vitro antioxidant properties, free radicals scavenging activities of extracts and polyphenol composition of a non-timber forest product used as spice: Monodora myristica. Biol Res. 2015;48:1–17. 10.1186/0717-6287-48-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freires IA, Sardi JC, de Castro RD, Rosalen PL. Alternative Animal and Non-Animal Models for Drug Discovery and Development: Bonus or Burden? Pharm Res. 2017;34:681–686. 10.1007/s11095-016-2069-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIFF)

(TIFF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.