Abstract

Objective:

To compare whites and African-Americans in terms of dementia risk following index stroke.

Methods:

The data consisted of billing and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis codes from the South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs office on all hospital discharges within the state between 2000 and 2012. The sample consisted of 68,758 individuals with a diagnosis of ischemic stroke prior to 2010 (49,262 white [71.65%] and 19,496 African-Americans [28.35%]). We identified individuals in the dataset who were subsequently diagnosed with any of 5 categories of dementia and evaluated time to dementia diagnosis in Cox Proportional Hazards models. We plotted cumulative hazard curves to illustrate the effect of race on dementia risk after controlling for age, sex, and occurrence of intervening stroke.

Results:

Age at index stroke was significantly different between the 2 groups, with African-Americans being younger on average (70.0 [SD 12.5] in whites versus 64.5 [SD 14.1] in African-Americans, P <.0001). Adjusted hazard ratios revealed that African-American race increased risk for ailS categories of dementia following incident stroke, ranging from 1.37 for AD to 1.95 for vascular dementia. Age, female sex, and intervening stroke likewise increased risk for dementia.

Conclusions:

African-Americans are at higher risk for dementia than whites within 5 years of ischemic stroke, regardless of dementia subtype. Incident strokes may have a greater likelihood of precipitating dementia in African-Americans due to higher prevalence of nonstroke cerebrovascular disease or other metabolic or vascular factors that contribute to cognitive impairment.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, dementia, MCI (mild cognitive impairment), survival analysis

Introduction

Stroke and dementia share a number of risk factors, including hypertension and diabetes,1–4 and stroke approximately quadruples the risk of dementia.5,6 Prevalence of dementia among those with stroke is approximately equal to that in individuals without stroke who are 10 years older.5 Cerebrovascular disease contributes to a majority of cases of dementia evaluated with autopsy7–9 These observations suggest that the burden of common forms of dementia may be mitigated by aggressive stroke prevention measures.

Both stroke and dementia are leading causes of serious disability, and spare no age, sex, or ethnic origin. However, African-Americans are more impacted by stroke than any other racial group.10 In addition, African-Americans are at higher risk than whites for dementia.11,12 Hypertension and other vascular risk factors likely underlie both of these disparities. Racial differences in the incidence of dementia among people with established cerebrovascular disease have not been well studied, especially in the highly stroke-prone southeastern US region. Such an investigation could lead to clinical research that informs the most appropriate treatment regimes, including modifications of recommendations based on physiological or behavioral differences.

Methods

Statewide encounter-level data were obtained from the South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office, which monitors all uniformed billing data for emergency department (ED) and inpatient discharges in the state, with the exception of Veterans Affairs or military health systems. Death certificate information, provided by the state Department of Health and Environment Control were linked to the discharge database. Individuals at least 18 years old with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), Clinical Modification 433.00–434.91 and 436) between 2000 and 2010 were identified. For individuals meeting criteria, data on all other inpatient and ED encounters from 2000 to 2012 regardless of diagnosis were obtained.

Analyses were limited to non-Hispanic African-American/black and white subjects as other race groups composed <2% of the sample. The final sample included 68,758 individuals, of whom 49,262 (71.65%) were white and 19,496 (28.35%) were African-American.

As a first analysis step, index (initial) strokes were identified. Individuals with transient ischemic attack or hemorrhagic stroke were not excluded, but these diagnoses were not considered index strokes (4511 individuals with previous events in these categories). Data following index strokes occurring prior to 2008 were censored at 5 years (1825 days) or at the date of death if it occurred within 5 years of discharge. Those occurring during or after 2008 were censored at December 31st, 2012 or at the time of death if it occurred prior to that date. Individuals with any dementia diagnosis prior to index stroke were excluded, but those with initial dementia diagnosis coincident with index stroke were retained and time to diagnosis was set at 0 days. Case fatalities at time of index stroke were excluded from analyses.

Second, dementia diagnoses were identified and sorted into codes representing Alzheimer disease (AD-8 ICD-9 codes), vascular dementia (4 ICD-9 codes), Alzheimer disease-related dementias (ADRD-13 additional codes distinct from the AD and vascular dementia codes), and non-ADRD (10 other ICD-9 dementia codes). We defined the outcome of “all-type” dementia as any dementia diagnosis code. We excluded diagnosis codes for neurodegenerative diseases that do not entail dementia, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Codes used for each category are listed in the Supplementary data. “Cases” were defined (for each analysis) as individuals who never received any dementia diagnosis prior to index stroke, but at some point subsequently received a dementia diagnosis code (respectively, any code for all-type dementia, ADRD, AD, non-ADRD, or vascular dementia).

Time to dementia diagnosis was entered as the dependent variable into Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) regression models. For each dementia diagnosis type, we assessed the racial composition of the sample in unadjusted analysis. Predictor variables in the adjusted CPH models included age, sex, race, intervening stroke, and the interaction of race and intervening stroke, where intervening stroke was defined as the presence of any stroke after the index stroke but prior to dementia diagnosis, death, or censoring. Cumulative hazard plots were generated to illustrate differences in dementia risk by race over 5 years of follow up, after adjusting for the other predictors. Stepwise selection was used to determine significant risk factors for each dementia diagnosis type via adjusted CPH models stratified by intervening stroke status. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All P values were 2-sided and considered significant at P <.05. This study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

The analytic sample included 68,758 nondemented individuals with ischemic stroke, of whom 71.65% were white and 28.35% black or African-American, 49% male, with mean age of 68 (SD 13) years. Age at index stroke was significantly different between the 2 groups, with African-Americans being younger on average (70.0 [SD 12.5] in whites vs. 64.5 [SD 14.1] in African-Americans, P <.0001). Table 1 shows unadjusted rates of diagnoses within the 5 categories of interest for whites and African-Americans. The proportion of individuals in this sample who developed dementia was 13.33% (n = 9163). Among whites, 12.7% developed dementia, compared to 15.0% among blacks. African-American race appeared to increase risk for all dementia diagnosis categories except AD (unadjusted hazard ratio .99; 95% confidence intervals [CI].93–1.06) and Non-ADRD (unadjusted hazard ratio 1.04; 95% CI (.97–1.11).

Table 1.

Unadjusted racial comparison of dementia within 5 years of index stroke by subtype

| Dementia sub type, n (%) | Total (n = 68,758) | White (n = 49,262) | African-American (n= 19,496) | Unadjusted HR (95% Cl) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause | 9,163 (13.33) | 6,240 (12.67) | 2,923 (14.99) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.28) | <.0001 |

| ADRD | 8350 (12.14) | 5694 (11.56) | 2656 (13.62) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | <.0001 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 4604 (6.70) | 3320 (6.74) | 1284 (6.59) | .99 (.93, 1.06) | .8649 |

| Vascular dementia | 3340 (4.86) | 2021 (4.10) | 1319 (6.77) | 1.69 (1.58, 1.82) | <.0001 |

| Non-ADRD | 4182 (6.08) | 2982 (6.05) | 1200 (6.16) | 1.04 (.97, 1.11) | .2832 |

ADRD, Alzheimer disease-related dementias; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratios.

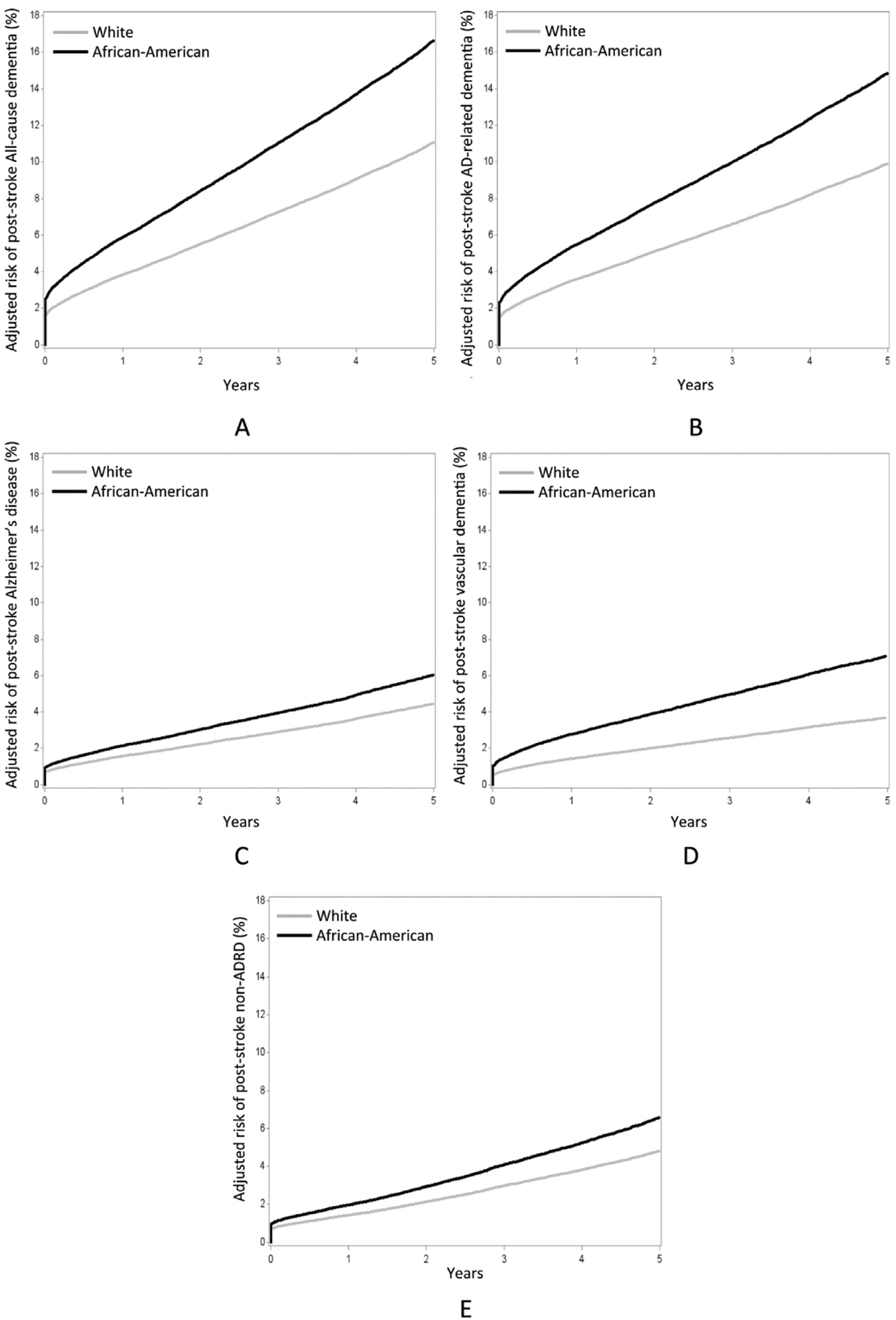

Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) and 95% CI are shown in Table 2 for the 5 sets of dementia diagnosis codes (columns) with the predictors of interest. African-American race increased risk for all 5 categories of dementia following incident stroke, ranging from 1.37 for AD to 1.95 for vascular dementia. Fig 1A–E depict the cumulative hazard for African-American and white individuals in each dementia diagnosis category after adjusting for all other predictors. The presence of intervening stroke significantly increased risk for all 5 categories of dementia, ranging from 5.27 for AD to 11.52 for vascular dementia. Female sex had no effect on risk of vascular dementia diagnosis, but otherwise increased risk for dementia up to a maximum aHR of 1.23 for AD. Each year of age increased risk of dementia, with aHR ranging from 1.05 for vascular dementia to 1.10 for AD.

Table 2.

Adjusted HR(95% Cl) of dementia by associated factors

| Factors | All-cause HR (95% Cl) | ADRD HR (95% Cl) | Alzheimer’s disease HR (95% Cl) | Vascular dementia HR (95% Cl) | Non-ADRD HR (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African-American | 1.55 (1.48, 1.63) | 1.54 (1.46, 1.62) | 1.37 (1.28, 1.47) | 1.95 (1.80, 2.11) | 1.38 (1.28, 1.48) |

| Intervening stroke | |||||

| No | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Yes | 8.99 (8.53, 9.47) | 8.59 (8.14,9.08) | 5.27 (4.87, 5.70) | 11.52 (10.63, 12.48) | 5.92 (5.47, 6.42) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) |

| Female | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.30) | - | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) |

| Age (years) | 1.07 (1.06, 1.07) | 1.07 (1.06, 1.07) | 1.10 (1.09, 1.10) | 1.05 (1.04, 1.05) | 1.08 (1.08, 1.09) |

ADRD, Alzheimer disease-related dementias; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratios; ref, reference.

Models are adjusted for all factors listed and the interaction of intervening stroke and race (P values for interactions are <.01 for all models, except for vascular dementia P =.54) with significant HRs presented.

Figure 1.

Adjusted cumulative incidence curves of (A) All-cause dementia, (B) Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia (ADRD), (C) Alzheimer’s disease, (D) Vascular dementia, (E) non-Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia (non-ADRD) by race group. Covariates in the adjusted Cox proportional hazards models include intervening stroke, gender, age, and the interaction of intervening stroke and race (interaction P < .01 for all models except vascular dementia, for which P =.54).

Table 3 shows adjusted HR for all 5 sets of dementia codes, stratified for individuals with or without intervening stroke. African-American race persisted as a risk factor for dementia following index stroke, with aHR ranging from 1.38 for AD to 2.02 for vascular dementia among those with no intervening stroke as compared to whites. Among those with an intervening stroke, African-American race increased the risk for all-cause dementia, ADRD, and vascular dementia compared to whites, but has no effect on non-ADRD; whereas white race increases the risk for AD as compared to African-American. Furthermore, risk for AD among African-Americans with an intervening stroke was relatively reduced (OR.84), while risk for AD among African-Americans without intervening stroke was substantially increased (OR 1.38).

Table 3.

Adjusted HR (95% CI) of dementia by associated factors stratified by intervening stroke status

| Factors | All-cause | ADRD | Alzheimer’s disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervening stroke | No intervening stroke | Intervening stroke | No intervening stroke | Intervening stroke | No intervening stroke | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| AA | 1.15 (1.05, 1.27) | 1.58 (1.50, 1.66) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) | 1.57 (1.49, 1.67) | .84 (.71,.98) | 1.38 (1.29, 1.48) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | - | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) |

| Female | - | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | - | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18) | - | 1.29 (1.20, 1.38) |

| Factors | Vascular dementia | Non-ADRD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervening stroke | No intervening stroke | Intervening stroke | No intervening stroke | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) |

| Black | 1.67 (1.46, 1.90) | 2.02 (1.86, 2.20) | - | 1.40 (1.30, 1.51) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | - | - | - | 1.00 (ref) |

| Female | - | - | - | 1.13 (1.05, 1.21) |

| Age (years) | - | 1.06 (1.05, 1.06) | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04) | 1.09 (1.08, 1.09) |

AA, African-American; ADRD, Alzheimer disease-related dementias; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratios; ref, reference. *Models adjusted for all factors found to be significant via stepwise regression.

Discussion

These data suggest that ischemic stroke imparts higher risk for dementia diagnosis in African-Americans than in whites within 5 years, regardless of dementia subtype. A review of previous studies of poststroke dementia indicates that the dementia risk at 1 year poststroke is approximately 25%.13 Our results indicate that in South Carolina, the risk of all-cause dementia at 1 year after initial stroke is approximately 11% for whites and 16% for African-Americans (Fig 1A). Hazard ratios for all forms of dementia considered here are higher for African-Americans, but the discrepancy is larger among individuals with no intervening stroke diagnosis. One interpretation for this finding is that nonstroke cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease (i.e., hypertension and aFib)/4–16 and metabolic diseases (i.e., diabetes and obesity)17,18 that contribute to cognitive impairment are highly prevalent among African-Americans even prior to stroke. As such, incident strokes may have a greater likelihood of precipitating dementia in African-Americans than in whites. The stratified analysis (Table 3) reveals that African-Americans with an intervening stroke have a reduced risk for subsequent diagnosis of AD (OR.84), while those without intervening stroke have an increased risk (OR 1.38). This interaction serves to explain why the adjusted model reveals an overall increased risk for AD that the unadjusted model does not detect.

We made the decision to censor at 5 years in order to control bias in varying lengths of follow-up times (i.e., some patients with up to 13 years versus some with less than 1 year of follow-up). We had some concern that other nonstroke vascular conditions that were not assessed may have contributed to dementia over longer follow-up periods. While 5 years of follow up may underestimate the true incidence of poststroke dementia, a sensitivity analysis allowing complete follow-up over the 13 year period (2000–2012) revealed no significant changes in the estimated hazards by race after adjusting for intervening stroke, gender, age, and the interaction of intervening stroke and race; thus 5 years appears to be adequate for the goals of this study (see supplemental Table e-1).

Previous studies have investigated the question of whether race and stroke interact to increase risk for cognitive decline, but have failed to find a relationship.19,20 The sample sizes for these studies were substantially smaller than for our study. One study had only 31 individuals with stroke out of 1130 participants19 and the other had 334 individuals with stroke out of 4908 participants (34 of whom were African-Americans).20 Thus, these studies might have been underpowered to detect an effect. Importantly, one cannot conclude on the basis of these studies that race and stroke do not interact in the genesis of dementia, as conventional statistical methods do not provide a basis for quantifying the probability of a null hypothesis. The striking racial disparity in poststroke dementia risk in our larger sample (9163 individuals with stroke and subsequent dementia, 2923 of whom were African-American) suggests that further exploration of a potential stroke x race interaction is warranted, and raises additional questions, such as whether the disparity persists in other stroke belt states or outside the stroke belt.

Due to the nature of our database, we were unable to account for the influence of other disparities known to be relevant. For example, educational level relates to risk for dementia,5 and African-Americans are more likely than whites to report a low level of formal education.21 Similarly, our database did not include information on socioeconomic status. Lower socioeconomic status may indirectly affect dementia risk, such as by reducing treatment adherence, access to healthier lifestyle options, or access to newer generations of antihypertensives. Our database did not contain stroke-free individuals to act as controls. Our database contained only healthcare encounter information (e.g., hospital discharge) and public records (deaths), so we could not account for these potentially important mediating variables. Finally, the diagnoses were rendered in inpatient or ED settings and were neither verified clinically in an outpatient setting nor pathologically confirmed. Nevertheless, the pattern of increased dementia risk among African-Americans following index ischemic stroke is robust across the spectrum of clinical diagnoses considered here, and warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.05.048.

References

- 1.Moroney JT, Bagiella E, Tatemichi TK, et al. Dementia after stroke increases the risk of long-term stroke recurrence. Neurology 1997;48:1317–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin YP, De Legge S, Ostbye T, et al. The reciprocal risks of stroke and cognitive impairment in an elderly population. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2006;2:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hersi M, Irvine B, Gupta P, et al. Risk factors associated with onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of the evidence. Neurotoxicology. 2017;61:143–187. 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu C, Xu W, Fratiglioni L. Vascular and psychosocial risk factors in Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiological evidence toward intervention. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;20:689–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rhonchi D, Palmer K, Pioggiosi P, et al. The combined effect of age, education, and stroke on dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia in the elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007;24:266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honig lS, Tang M-X, Albert S, et al. Stroke and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol2003;60:1707–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, et al. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology 2007;69:2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Crane PK. Pathological correlates of dementia in a longitudinal, population-based sample of aging. Ann Neurol2007;62:406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savva GM, Wharton SB, Ince PG, et al. Age, neuropathology, and dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2302–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleindorfer D Sociodemographic groups at risk: race/ethnicity. Stroke 2009;40(suppl1):S75–S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glymour MM, Kosheleva A, Wadley VG, et al. Geographic distribution of dementia mortality. Elevated mortality rates for black and white Americans by place of birth. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2011;25:196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manly JJ, Mayeux R. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendlebury ST. Dementia in patients hospitalized with stroke: rates, time course, and clinico-pathologic factors. Int J Stroke 2012;7:570–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Elbaz A, et al. Predicting cognitive decline: a dementia risk score vs. the Framingham vascular risk scores. Neurology 2013;80:1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Nabi H, et al. Predictive utility of the Framingham general cardiovascular disease risk profile for cognitive function: evidence from the White hall II study. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2326–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viticchi G, Falsetti L, Buratti L, et al. Framingham risk score can predict cognitive decline progression in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36:2940–2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luchsinger J, Gustafson DR. Adiposity, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheirners Dis 2009;16:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts AS, Loskutova N, Burns JM, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in early Alzheimer’s disease and healthy older adults. J Alzheimers Dis 2013;35:253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knoprnan D, Mosley TH, Catellier DJ, et al. Fourteenyear longitudinal study of vascular risk factors, APOE genotype, and cognition: The ARIC MRl Study. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2009;5:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine DA, Kabeto M, Langa KM, et al. Does stroke contribute to racial differences in cognitive decline? Stroke 2015;46: 1897–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sautter JM, Thomas PA, Dupre ME, et al. Socioeconomic status and the black-white crossover. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1566–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.