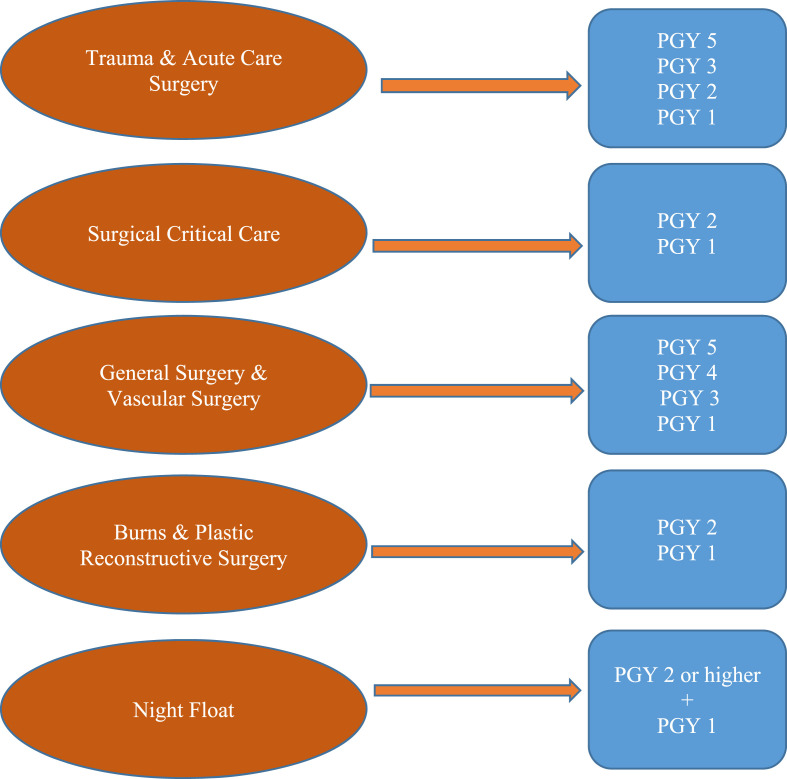

As of May 12, 2020, in the US, COVID-19 has been confirmed in all 50 states with 1,356,037 confirmed cases and over 81,000 deaths.1 In Florida, there is currently 41,923 confirmed cases with 1779 deaths1 with the highest concentration in the South Florida region. Our hospital is a Level 1 Trauma Center with 417-bed hospital providing care to the residents of South Florida. The General Surgery Residency Program consists of 27 surgical residents who rotate between two main hospitals with two residents at a time (PGY 3 and PGY 4) rotating at outside hospitals. At the primary hospital, there is a total number of 13 surgical residents at all times split between four surgical subspecialties: Trauma & Acute Care Surgery, Surgical Critical Care, General & Vascular, and Burn & Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. There is also an intern night float with a PGY 2–5 through PGY 5 acting as the senior resident on call every night.

COVID-19 has impacted the training process of medical students, residents, and fellows.2 Through the collaboration between the Surgical Department leadership team at our Level 1 Trauma Center with the faculty, Chief Residents, Senior and Junior level residents, the rotations were restructured in such a way to minimize the amount of exposure to COVID-19 positive patients, eliminate scheduled gatherings of more than 10 people, alleviate residents burnout, maintain their mental health wellbeing, while continuing to provide educational activities and conferences.

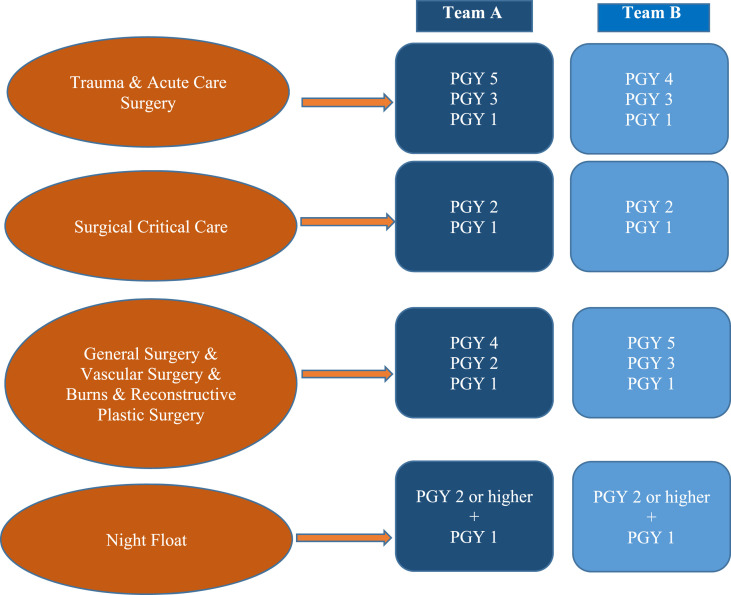

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the General & Vascular Surgery Team suffered a significant reduction in surgical volume. Thus, the four rotations at our program were changed to three rotations with the General & Vascular Surgery Team combining with the Burn & Plastic Reconstructive Surgery team. Resident coverage was reduced by 50%. The new rotations as well as the night float then have two separate teams that rotate weekly. Team A works for 7 days as a Clinical Week and then 7 days as a Didactic & Scholarly week. Team B alternates, working 7 days as a Didactic & Scholarly week and then 7 days as a clinical week (Fig. 1 ). When creating the schedule, the social structure of the residency was taken into account. If residents socialized outside of the hospital normally, they would be on the same team to avoid cross contamination through social interactions that still abided by the Stay-At-Home order. The utmost importance however, was the balance between the level of training to make sure both teams had equal representation of junior and senior residents (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Pre COVID-19 general surgery residency program structure.

Fig. 2.

General surgery residency program structure during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our colleagues at other institutions have approached the COVID-19 pandemic with changes to their residency structure as well.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Depending upon the healthcare system for which they are a part of and how they are integrated in that system as a whole determined how they restructured their respective training. Both similarities and differences can be seen throughout the restructuring.

The Department of Orthopedic Surgery at Johns Hopkins developed an operational plan in order to protect the workforce while providing essential clinical care and maintain the continuity of education and research.4 Their hospital group was also split into 2 teams, Team A and Team B, that worked alternating 14-day shifts. Team A works clinical in-hospital duty and Team B works remotely in hopes to minimize exposure and to allow the opposite team to act as a reserve in the scenario that one of the members of the opposite team falls ill.

The general surgery residency at The University of Washington developed a 3-team approach that rotates weekly: inpatient care, operating care, and clinical care.5 All teams work in isolation from one another in order to prevent the spread COVID-19 if a team member were to contract the virus. Additionally, they utilized virtual hand-offs in order to transition patient care between teams and between day and night.

Drastically different compared to our restructuring was The Department of Surgery at The University of Wisconsin. Their approach was cross-departmental with a content expert overseeing 4 teams that are staffed with clinicians of varying levels.6 These teams would work 5-day blocks and 12-h shifts in order to provide a balance between clinician’s physical and psychological safety as well as minimizing hand-offs during patient care transition.

Internationally, we have also gained insight into their method of continuing surgical education with their residents. Throughout Europe, surgical trainees are being asked to serve roles that can be non-related to surgery, however involve care for COVID-19 patients in areas where there is a shortage of personnel.7

Due to the decreased number of surgical volume and operations, all services and cases are still able to be fully covered by the residents despite the downsize. Patient care is still optimized as the services with the most patients (Trauma & Acute Care Surgery and Surgical Critical Care) still have an adequate number of residents to care for the patients and cover the operations, as well as having residents from the combined service cross-cover whenever required. During the Didactic & Scholarly week, residents are off-site from the hospital and abiding by the Florida Stay-At-Home mandate. Residents are expected to partake in the following activities depending on their level of training via virtual learning: management discussions regarding daily COVID-19 planning, fellowship applications and interviews, scholarly activity in the form of research, academic lecture, and morbidity & mortality conference. Management discussions, academic lecture and morbidity & mortality take place via teleconference through a secured teleconference meeting that can be called in to through telephone or accessed through an application through the smartphone or computer if power point is required.

The immediate effect of the pandemic on surgical education is the steep decline in cases close to graduation. Cancellation of all elective surgical cases severely decreased the number of cases for the surgical residents. Prior to the emergency schedule, the surgery residents logged a mean of 21 major defined cases per day. For the 6 weeks on emergency scheduling, the average major defined cases per day dropped to 10, the vast majority were emergency cases related to our Trauma Center, Burn Center, or emergency general surgery. There were 41 elective cases done, or about 1 per day, that were related to potentially aggressive cancers, symptomatic abdominal pain, or symptomatic vascular disease. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has confirmed that surgery residents and fellows can still graduate without having achieved all the case minima, dependent upon the clearance of the Program Director with input from the Clinical Competency Committee about whether the trainee is capable of practicing safely without supervision.8 Fortunately, since the pandemic struck towards the end of the academic year, our current Chiefs (graduating PGY 5s) are still on track to complete their minimum amount of required cases. The longer-term effect of the steep decline in elective cases is the surgical experience of the current PGY 4s. Depending upon the time taken to transition back to a regular schedule as well as elective cases returning, this could hinder the surgical education in terms of operative experience of the rising chief residents. We continue to closely monitor and follow the recommendations of the ACGME in regards to this, as this is still an evolving situation that changes on a daily basis.8

Reforming the residency to two separate teams with an acceptable number of residents to deliver care and cover operations will also reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection. While the residents are practice proper safety with personal protective equipment in the hospital on their clinical week, this still poses an exposure risk. There is, however, another team of residents who are not at the hospital who are low exposure risk. This allows a resident from the opposite team to be on backup in order to cover if a resident were to contract COVID-19 and require quarantine or hospitalization. The use of secured teleconferencing for academic lecture and morbidity & mortality can also be expanded towards the use of web-based virtual learning in making decisions. Lecture modules can be used to further solidify the training and clinical decision making of residents in times of decreased patient contact in the hospital setting. This will ensure that residents still maintain their clinical decision-making skills.

Burnout and resident mental health are also being affected by the current pandemic. While previous studies have shown that lack of self-care has been associated with emotional exhaustion and lack of personal accomplished,9 residents on their Scholarly & Didactic week may have more time to attend to self-care within the limits of the Stay-At-Home order, which can lead to less symptoms of burnout and improved resident mental health. We consider resident well-being of high importance. Although we do not have an objective measure of resident well-being, chief residents are in close communication with their respective team residents. Any concerns were brought up and addressed in order to maintain both physical and mental well-being in an unprecedented time when the day-to-day work schedule can drastically change. Additionally, weekly updates from residents after their Scholarly & Didactic week allows us to keep close updates on residents.

As the COVID-19 pandemic begins to decrease in number and as elective surgeries resume, the plan is to transition our residents back to their original clinical and academic duties prior to the pandemic. Our residents’ safety and wellbeing has been always been a priority, and it still remains of utmost at this time of crisis. Our commitment to our residents and ensuring that they are safely trained and protected from harm has never been more important than in a time like now. A healthy and safe residency program is indeed defined by the safety and wellbeing of its residents and through the measures we have taken, we have been able to provide this to our residents.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html Published, Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 2.Calhoun Kristine E., Yale Laura A., Whipple Mark E., Allen Suzanne M., Tatum Roger P. 28 April 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Student Surgical Education: Implementing Extreme Pandemic Response Measures in a Widely Distributed Surgical Clerkship Experience the American Journal of Surgery in Press. corrected proofAvailable online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin Allison N., Petroze Robin T. 14 May 2020. Academic Global Surgery and COVID-19: Turning Impediments into Opportunities the American Journal of Surgery in Press. corrected proof Available online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabharwal S., Ficke J., Laporte D. How we do it: modified residency programming and adoption of remote didactic curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nassar A.H., Zern N.K., McIntyre L.K. Emergency restructuring of a general surgery residency program during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: the university of Washington experience. JAMA Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarzaur B.L., Stahl C.C., Greenberg J.A., Savage S.A., Minter R.M. Blueprint for restructuring a department of surgery in concert with the health care system during a pandemic: the University of Wisconsin experience. JAMA Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco-Colino R., Soares A.S., Kuiper S.Z., Zafforini G., Pata F., Pellino G. Surgical training during and after COVID-19: a joint trainee and trainers manifesto. Ann Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACGME Specialty letters to the community. April 15, 2020. www.acgme.org/COVID-19/Specialty-Letters-to-the-Community Published 2020. Accessed.

- 9.Eckleberry-Hunt Jodie. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269–277. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181938a45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]