Abstract

Background

International professional bodies have been quick to disseminate initial guidance documents during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the absence of firm evidence, these have been developed by expert committees, limited in participant number. This study aimed to validate international COVID-19 surgical guidance using a rapid Delphi consensus exercise.

Methods

Delphi statements were directly mapped to guidance from surgical professional bodies in the US and Europe (SAGES/EAES), the UK (Joint RCS), and Australasia (RACS), to validate content against international consensus. Agreement from ≥70% participants was determined as consensus agreement.

Results

The Delphi exercise was completed by 339 individuals from 41 countries and 52 statements were mapped to the guidance, 47 (90.4%) reaching consensus agreement. Of these, 27 statements were mapped to SAGES/EAES guidance, 21 to the Joint RCS document, and 33 to the RACS document. Within the SAGES/EAES document, 92.9% of items reached consensus agreement (median 89.0%, range 60.5–99.2%), 90.4% within the Joint RCS document (87.6%, 63.4–97.9%), and 90.9% within the RACS document (85.5%, 18.7–98.8%). Statements lacking consensus related to the surgical approach (open vs. laparoscopic), dual consultant operating, separate instrument decontamination, and stoma formation rather than anastomosis.

Conclusion

Initial surgical COVID-19 guidance from the US, Europe and Australasia was widely supported by an international expert community, although a small number of contentious areas emerged. These findings should be addressed in future guidance iterations, and should stimulate urgent investigation of non-consensus areas.

Keywords: COVID-19, Delphi consensus, Guidance, Surgery

Highlights

-

•

339 international experts across 41 countries participated in this Delphi process on surgical practice in COVID-19.

-

•

90–93% agreement with guidance from SAGES/EAES (US/Europe), Joint UK Royal Colleges, Royal Australasian College of Surgery.

-

•

This study validates the guidance issued by these bodies.

-

•

A small number of contentious issues require urgent attention.

1. Introduction

Surgical practice has rapidly changed in response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic [1]. Many hospitals have quickly filled to capacity with non-surgical patients and a substantial, yet poorly understood, risk from COVID-19 to staff and patients has emerged [2].

International professional bodies have been quick to disseminate initial guidance documents during the COVID-19 pandemic [[3], [4], [5]]. In the absence of firm evidence [6], and with insufficient time to consult their memberships, guidance has been based predominantly on experiential reports and has been developed by expert committees within these professional bodies; limited in participant number, yet far-reaching in influence [7]. Such leadership, while helpful in aligning early OR practice, is not comprehensive, and cannot hope to integrate the perspectives of the wider medical community. With this approach comes a risk of disproportionate reliance upon a limited perspective, and the representativeness of the guidance produced is unclear [7].

This study aimed to validate the emerging international guidance on surgical practice in COVID-19 against wider international expert consensus.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This study was reported in line with STROCSS [8] and is registered online at http://researchregistry.com (UIN: researchregistry5675) [9].

Participation in this consensus study was open to all stakeholders in relation to OR practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stakeholders were defined as individuals whose work related to the OR (including endoscopy and dentistry), or who had specific knowledge relevant to the novel coronavirus.

COVID-19 surgical guidance documents from (i) the Society of American Gastroenterological Surgeons/European Association of Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES/EAES), (ii) the Joint Royal Colleges of Surgeons (Joint RCS) in the United Kingdom, and (iii) the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS), were deconstructed to extract their individual component items, which were mapped to statements produced within a Delphi consensus process, either a priori (SAGES/EAES and Joint RCS) or post hoc (RACS), if issued after the consensus exercise started.

2.2. Data sources and delphi methodology

In a recent rapid systematic review of OR practice in COVID-19, the very limited nature of the literature base was reported, with a clear need for a novel methodological approach during the rapidly emerging pandemic [6]. Four key domains of OR practice emerged; physical resources, personnel factors, patient factors, and procedure-related factors. The earlier systematic review informed the development of the methodology employed in this mapping study of Delphi consensus responses to guidance items.

Twitter was chosen as the social media platform for delivery for two reasons. First, because of its ability to allow global distribution and engagement, and second, because of its automatic online cataloguing of responses and ability to flag themes, using the hashtag symbol (e.g. #surgery). This permitted rapid turnaround of a high number of responses in order to expedite project progression. A dedicated Twitter account (@OpCOVID) was created to act as the vehicle for distribution and collection of stakeholder interactions.

Phase I - Question collation. Stakeholders were requested, via Twitter, to provide questions relating to the four domains of OR practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. The project was promoted by OpCOVID collaborators via personal Twitter accounts and direct engagement of relevant stakeholders, paying particular attention to relevant, prominent Twitter users. Questions contributed were reviewed by three collaborators (AB, CB, RE), to assess for repetition, themes, and relevance.

Phase II - Question answering. Firstly, identified questions were presented to stakeholders via Twitter, with an invitation to report personal and observed practices and experiences, and to signpost relevant evidence and guidance. Meanwhile, collaborators simultaneously interrogated the literature for emerging evidence-based answers and guidance; this evidence was used to stimulate on-going discussion. All responses were extracted, recorded, and the resources identified were downloaded for phase III analysis. During this phase, the same three collaborators (AB, CB, RE) used the deconstructed international guidance items, alongside all other data collected via the social media campaign, to directly inform the development of relevant Delphi statements, in order to ensure effective mapping to the guidance would be possible.

Phase III - Consensus exercise. Answers from phase II were used to develop a series of statements within a modified Delphi questionnaire, delivered using Google Forms. Where evidence and/or guidance were identified in phases I and II, these were signposted within the Delphi statement, including links directly to the source(s). A single-round exercise was employed to maximise participation and permit rapid completion. Global Delphi participants were sought via social media emails to stakeholder organisations, and electronic contact with relevant collaborator contacts. Demographic data collected within the Delphi exercise included country of practice, area of expertise, stage of training, and highest academic qualification.

2.3. Data analysis

A three-point Likert scale was used (one = agree; two = unsure; three = disagree), with an escape option (outside of my expertise) if required. ‘Consensus agree’ (consensus that the statement was appropriate) was defined as more than 70% of participants allocating an item a score of one AND fewer than 25% of participants allocating a score of three. ‘Consensus disagree’ (consensus that the statement was not appropriate) was defined as more than 70% of participants allocating an item a score of one AND fewer than 25% of participants allocating a score of three. ‘Non-consensus’ was defined as more than 33% of participants allocated an item a score of one AND 33% or more allocating a score of three. All other combinations were considered ‘equivocal’.

All Delphi statements directly related to a given extracted guidance item were reported. The median (range) agreement was reported and, where any statement was relevant to more than one guidance item, de-duplication ensured it was counted once only in consensus calculations for each guidance document.

3. Results

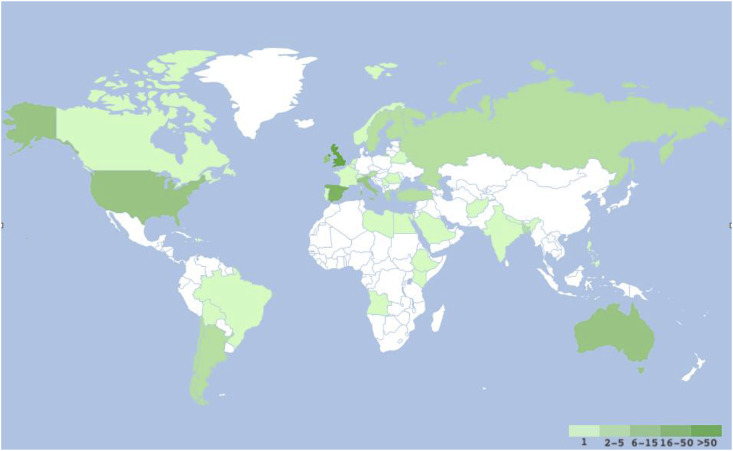

The Delphi exercise was completed by 339 experts, from 41 countries (Table 1 ), covering all six World Health Organization (WHO) regions (Fig. 1 ). A majority of participants were at attending/consultant level (204, 60%), and most were surgeons (282 [82%]). Most participants held a doctorate or masters degree (258, [75%] Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of the participants: specialism, grade and academic achievement.

| Specialty | n (%) | Grade | n (%) | Highest Academic Achievement | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | 279 (82.3) | Attending or equivalent | 204 (60.2) | Doctorate | 137 (40.4) |

| Anaesthesiologist/Intensivist | 29 (8.6) | Resident or equivalent | 96 (28.3) | Masters | 119 (35.1) |

| Other Medical Professional | 16 (4.7) | Intern or equivalent | 21 (6.2) | Bachelor | 74 (21.8) |

| Nurse | 9 (2.7) | N/A | 18 (5.3) | Other | 9 (2.7) |

| Operating Department Practitioner | 5 (1.5) | ||||

| Other Non-Medical Professional | 1 (0.3) |

CONSENSUS AGREEMENTS.

Consensus agree: >70% agree, <25% disagree.

Consensus disagree: >70% disagree, <25% agree.

Non-consensus: ≥33% agree, ≥33% disagree.

Equivocal: All other combinations.

Fig. 1.

Choropleth of Delphi participation.

3.1. SAGES/EAES document

The content of the SAGES/EAES document is shown, mapped to consensus statements, in Table 2 . Consensus was generally very high with a median consensus of 89.0% (range 60.5–99.2%). Of 27 Delphi statements (de-duplicated from 32), relating to 26 guidance items, 26 (92.9%) reached consensus agreement.

Table 2.

Society of American Gastroenterological and Endoscopic Surgeons/European Association of Endoscopic Surgeons guidance mapped to Delphi statements.

| Published guidance item |

Agree (%) | Unsure (%) | Disagree (%) | Outside of expertise (n/330) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guidance mapped to Delphi statement(s) | ||||

| Rationing | ||||

| All elective surgical and endoscopic cases should be postponed at the current time. These decisions however should be made locally, based on COVID-19 burden and in the context of medical, logistical and organizational considerations. There are different levels of urgency related to patient needs, and judgment is required to discern between them. However, as the numbers of COVID-19 patients requiring care is expected to escalate over the next few weeks, the surgical care of patients should be limited to those whose needs are imminently life threatening. These may include patients with malignancy that could progress, or with active symptoms that require urgent care. All others should be delayed until after the peak of the pandemic is seen. This minimizes the risk to both, patient and health care team, as well as minimizes utilization of necessary resources, such as beds, ventilators, and personal protective equipment (PPE). | ||||

| All elective work should be postponed at present unless delay substantially affects the prognosis | 91.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1 |

| All non-essential hospital or office staff should be allowed to stay home and telework. All in-person educational sessions should be cancelled and could be replaced by online resources. The minimum number of necessary providers should attend patients during rounds and other encounters. Adherence to hand washing, antiseptic foaming, and appropriate use of PPE should be strictly enforced. When necessary, in-person surgical consultation should be performed by decision makers only. | ||||

| The minimum number of necessary providers should attend patients during rounds and other encounters | 99.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1 |

| All non-urgent in-person clinic/office visits should be cancelled or postponed, unless needed to triage active symptoms or manage wound care. All patient visits should be handled remotely when possible, and in person only when absolutely necessary. Access to clinics should be maintained for those special circumstances to avoid patients seeking care in the ED. Only a minimum of required support personnel should be present for these visits, and PPE should again be appropriately utilized. When in critical need, consideration should be given to redeploying OR resources for intensive care needs. | ||||

| All in-person clinic/office work should be cancelled or delivered electronically, unless this substantially affects the prognosis | 93.8 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 1 |

| Multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings should be held virtually as possible and/or limited to core team members only, including surgeon, pathologist, Clinical Nurse Specialist, radiologist, oncologist and coordinator. The MDT is responsible for the decision making and classifying the patient's priority level of need for surgery. | ||||

| MDTs should be conducted virtually where possible | 96.7 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 2 |

| Decisions regarding management strategies should be taken by the MDT wherever possible | 96.5 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 4 |

| Procedural | ||||

| It is strongly recommended however, that consideration be given to the possibility of viral contamination to staff during surgery either open, laparoscopic or robotic and that protective measures are strictly employed for OR staff safety and to maintain a functioning workforce. | ||||

| Viral contamination of staff is possible during surgery either open, laparoscopic or robotic surgery | 92.3 | 1.9 | 5.9 | 16 |

| Proven benefits of MIS of reduced length of stay and complications should be strongly considered in these patients, in addition to the potential for ultrafiltration of the majority or all aerosolized particles. Filtration of aerosolized particles may be more difficult during open surgery. | ||||

| Filter devices be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy | 88.1 | 2.3 | 9.6 | 36 |

| There may be enhanced risk of viral exposure to proceduralists/endoscopists from endoscopy and airway procedures. When these procedures are necessary, strict use of PPE should be considered for the whole team, following Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or WHO guidelines for droplet or airborne precautions. This likely includes, at a minimum, N95 masks and face shields. | ||||

| Where endoscopy is essential, staff should wear the recommended PPE appropriate for an AGP | 95.6 | 0 | 4.4 | 23 |

| There is very little evidence regarding the relative risks of Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) versus the conventional open approach, specific to COVID-19. We will therefore continue to monitor emerging evidence and support novel research to address these issues. | ||||

| [No mapped statement available] | ||||

| Although previous research has shown that laparoscopy can lead to aerosolization of blood borne viruses, there is no evidence to indicate that this effect is seen with COVID-19, nor that it would be isolated to MIS procedures. Nevertheless, erring on the side of safety would warrant treating the coronavirus as exhibiting similar aerosolization properties. For MIS procedures, use of devices to filter released CO2for aerosolized particles should be strongly considered. | ||||

| Laparoscopy should be considered a coronavirus aerosol generating procedure | 74.5 | 6.9 | 18.6 | 33 |

| Practical measures | ||||

| Consent discussion with patients must cover the risk of COVID-19 exposure and the potential consequences. | ||||

| Consent discussions with patients must cover the added risk of COVID exposure and the potential consequences | 95.9 | 0 | 4.1 | 1 |

| If readily available and practical, surgical patients should be tested pre-operatively for COVID-19. | ||||

| Where safe and possible, surgical patients should be tested pre-operatively for COVID-19. | 94.7 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 1 |

| If needed and possible, intubation and extubation should take place within a negative pressure room. | ||||

| Intubation and extubation should take place within a negative pressure room where possible | 89.4 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 27 |

| Operating rooms for presumed, suspected or confirmed COVID-19 positive patients should be appropriately filtered and ventilated and if possible, should be different than rooms used for other emergent surgical patients. Negative pressure rooms should be considered, if available. | ||||

| Operating rooms should be filtered and ventilated, ideally with negative pressure, for CV19 patients | 87.2 | 2.8 | 10 | 19 |

| Separate operating rooms and access routes should be used for patients with COVID | 94.1 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2 |

| Only those considered essential staff should be participating in the surgical case and unless there is an emergency, there should be no exchange of room staff. | ||||

| Only essential staff should be in the OR for CV19 patients, with no exchange of room staff, except for emergency situations. | 97.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1 |

| All members of the OR staff should use PPE as recommended by national or international organization including the WHO or CDC. Appropriate gowns and face shields should be utilized. These measures should be used in all surgical procedures during the pandemic regardless of known or suspected COVID status. Placement and Removal of PPE in should be done according to CDC guidelines. | ||||

| PPE definition should universally be based on WHO guidance to avoid confusion | 82.6 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 6 |

| In the non-theatre environment PPE should follow WHO guidance: 1. Close contact - Mask, gown, gloves, face mask/googles. 2. AGP - Respirator (FFP2/N95), gown, gloves, face mask/googles, sleeved apron | 88.6 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5 |

| All patients should be considered to be COVID contagious unless proven otherwise during the pandemic | 89.9 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 4 |

| Electrosurgery units should be set to the lowest possible settings for the desired effect. Use of monopolar electrosurgery, ultrasonic dissectors, and advanced bipolar devices should be minimized, as these can lead to particle aerosolization. If available, monopolar diathermy pencils with attached smoke evacuators should be used. | ||||

| Electrocautery should be used sparingly and on the lowest possible settings for the desired effect | 76.5 | 6.1 | 17.4 | 29 |

| Use of devices that can lead to promote aerosolization (monopolar electrosurgery, ultrasonic dissectors, advanced bipolar devices) should be minimized. | 80.4 | 3.4 | 16.3 | 13 |

| Monopolar diathermy pencils with attached smoke evacuators should be preferred if electrosurgery is required | 87.6 | 0.6 | 11.8 | 25 |

| Surgical equipment used during procedures with COVID-19 positive or Persons Under Investigation (PUI)/suspected COVID patients should be cleaned separately from other surgical equipment. | ||||

| Surgical equipment used in patients with COVID should have separate decontamination pathways | 60.5 | 20.3 | 19.2 | 48 |

| Laparoscopy | ||||

| Incisions for ports should be as small as possible to allow for the passage of ports but not allow for leakage around ports. | ||||

| Laparoscopic port site incisions should be kept as small as possible | 84.8 | 4.6 | 10.6 | 37 |

| CO2 insufflation pressure should be kept to a minimum and an ultra-filtration (smoke evacuation system or filtration) should be used, if available. | ||||

| Filter devices be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy | 88.1 | 2.3 | 9.6 | 36 |

| Laparoscopic port site incisions should be kept as small as possible | 84.8 | 4.6 | 10.6 | 37 |

| All pneumoperitoneum should be safely evacuated via a filtration system before closure, trocar removal, specimen extraction or conversion to open. | ||||

| Filter devices be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy | 88.1 | 2.3 | 9.6 | 36 |

| Endoscopy | ||||

| The ability to control aerosolized virus during endoscopic procedures is lacking, so all members in the endoscopy suite or operating room should wear appropriate PPE, including gowns and face shields. Placement and Removal of PPE should be done according to CDC guidelines. | ||||

| PPE practice in endoscopy should mirror that of any other AGP | 94.6 | 1 | 4.4 | 44 |

| Since patients can present with gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19, all emergent endoscopic procedures performed in the current environment should be considered as high risk. | ||||

| PPE practice in endoscopy should mirror that of any other AGP | 94.6 | 1 | 4.4 | 44 |

| Since the virus has been found in multiple cells in the gastrointestinal tract and all fluids including saliva, enteric contents, stool and blood, surgical energy should be minimized. | ||||

| Electrocautery should be used sparingly and on the lowest possible settings for the desired effect | 76.5 | 6.1 | 17.4 | 29 |

| Removal of caps on endoscopes could release fluid and/or air and should be avoided. | ||||

| Removal of caps on endoscopes could release fluid and/or air and should be avoided | 76 | 4.3 | 19.7 | 106 |

| Endoscopic procedures that require additional insufflation of CO2or room air by additional sources should be avoided until we have better knowledge about the aerosolization properties of the virus. This would include many of the endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoluminal procedures. | ||||

| Endoscopic procedures involving additional insufflation (e.g. endoscopic mucosal resection), should be avoided during the pandemic | 74.6 | 4.8 | 20.6 | 87 |

| Endoscopic equipment used during procedures with COVID-19 positive or PUI patients should be cleaned separately from other endoscopic equipment. | ||||

| Surgical equipment used in patients with COVID should have separate decontamination pathways | 60.5 | 20.3 | 19.2 | 48 |

The only statement not reaching consensus related to decontamination of surgical and endoscopic equipment in cases involving persons suspected or known to have COVID-19. Although not reaching consensus, a majority of 60.4% supported using separate decontamination pathways, the remaining two fifths equally split between being unsure (20.3%), and in disagreement (19.2%).

3.2. Joint RCS document

The content of the Joint RCS document is mapped to consensus statements in Table 3 . Consensus was again very high with a median consensus of 87.6% (range 63.4–97.9%). Of 21 statements (de-duplicated from 25), 19 (90.4%) reached consensus agreement.

Table 3.

– Joint United Kingdom Royal College of Surgeons guidance mapped to Delphi statements.

| Published guidance item |

Agree (%) | Unsure (%) | Disagree (%) | Outside of expertise (n/339) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guidance mapped to Delphi statement(s) | ||||

| 0. Increased risks apply to all patients. | ||||

| [Reverse wording] Screening questions are a poor way to identify potential patients with COVID | 73.4 | 17.2 | 9.4 | 0 |

| 1. Acute patients are our priority. COVID-19 should be sought in any patient needing emergency surgery: use history, COVID-19 testing, recent CT chest (last 24h) or failing that CXR. Any patient undergoing abdominal CT scan should also have CT chest. Current tests for COVID-19 may be false negative. | ||||

| The thorax should be included in emergency abdominal CT scans in patients with unknown COVID status | 90.2 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 0 |

| While false negative rates remain substantial, COVID status should be assessed using a CT thorax in patients with unknown COVID status requiring (non-emergent) urgent surgery (e.g. cancer) | 70.8 | 18.7 | 4.3 | 0 |

| 2. Any patient currently prioritised to undergo urgent planned surgery must be assessed for COVID-19 as above and the current greater risks of adverse outcomes factored into planning and consent. Consider stoma formation rather than anastomosis to reduce need for unplanned post-operative critical care for complications. | ||||

| Where safe and possible, surgical patients should be tested pre-operatively for COVID-19. | 94.7 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 0 |

| Consent discussions with patients must cover the added risk of COVID exposure and the potential consequences | 95.9 | 4.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Predicted length of stay and impact upon need for ITU should be taken into account in the procedure choice | 90.9 | 7 | 2.1 | 0 |

| Stoma formation should be considered rather than anastomosis to reduce the need for unplanned post-operative critical care for complications | 64 | 15.8 | 20.2 | 0 |

| 3. All theatre staff should use PPE during all operations under general anaesthetic whether by laparoscopy or laparotomy and infection control practices should be followed, as determined by local and national protocol. Those protocols advise on levels of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) based on risk from proximity to potential viral load. When COVID-19 status is positive or uncertain, international experience recommends Full Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) be used for laparotomy but shortages prevent this in most areas and stratification is necessitated with lesser measures for low-risk cases. Full PPE is advised for positive or suspected patients and includes double layers of disposable gloves and gown, eye protection and FFP3 mask. It is imperative to practise sterile donning and doffing of PPE in advance. Procedural tasks are slower and more difficult when wearing full PPE. In low risk patients it may be pragmatic currently to use appropriately reduced measures, including a type 2R fluid resistant mask with visor and disposable gown and gloves as a minimum. | ||||

| PPE level should be determined by (inter)national guidance rather than local policy | 85.4 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 0 |

| The minimum standard for "full" PPE should include: double layers of disposable gloves, water-resistant gown with full length sleeves, eye protection, and N95-99/FFP2-3 mask | 91.9 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 0 |

| All staff in theatre should use the same level of PPE for patients with COVID, regardless of proximity to the patient | 74.2 | 10.5 | 15.3 | 0 |

| Maximal level PPE should be worn for any laparotomy in patients with COVID | 93.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 0 |

| 4a. Laparoscopy is considered to carry some risks of aerosol-type formation and infection and considerable caution is advised. The level of risk has not been clearly defined and it is likely that the level of PPE deployed may be important. Advocated safety mechanisms (filters, traps, careful deflating) are difficult to implement. Consider laparoscopy only in selected individual cases where clinical benefit to the patient substantially exceeds the risk of potential viral transmission in that particular situation. | ||||

| Laparoscopy should be considered a coronavirus aerosol generating procedure | 74.5 | 18.6 | 6.9 | 0 |

| Filter devices be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy | 88.1 | 9.6 | 2.3 | 0 |

| 4b. Where non-operative management is possible (such as for early appendicitis and acute cholecystitis) this should be implemented. Appropriate non-operative treatment of appendicitis and open appendicectomy offer alternatives. | ||||

| An open approach should be favoured over laparoscopy unless the clinical benefit substantially exceeds the risk of potential viral transmission | 63.4 | 15.9 | 20.7 | 0 |

| Predicted length of stay and impact upon need for ITU should be taken into account in the procedure choice | 90.9 | 7 | 2.1 | 0 |

| Non-operative management should be preferentially implemented where possible | 85.5 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 0 |

| Trauma injuries should preferentially be managed non-surgically where this appears safe in the short term | 77.8 | 14.9 | 7.3 | 0 |

| 5a. Minimum number of staff in theatre | ||||

| Only essential staff should be in the OR for CV19 patients, with no exchange of room staff, except for emergency situations. | 97.9 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0 |

| 5b. Appropriate PPE for all staff in theatre depending on role and risk | ||||

| All staff in theatre should use the same level of PPE for patients with COVID, regardless of proximity to the patient | 74.2 | 10.5 | 15.3 | 0 |

| 5c. Smoke evacuation for diathermy/other energy sources | ||||

| Monopolar diathermy pencils with attached smoke evacuators should be preferred if electrosurgery is required | 87.6 | 11.8 | 0.6 | 0 |

| 5d. Team changes will be needed for prolonged procedures in full PPE | ||||

| Only essential staff should be in the OR for CV19 patients, with no exchange of room staff, except for emergency situations. | 97.9 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0 |

| 5e. Higher risk patients are intubated and extubated in theatre – staff immediately present should be at a minimum. | ||||

| Only essential staff should be in the OR for CV19 patients, with no exchange of room staff, except for emergency situations. | 97.9 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0 |

| 6. Only emergency endoscopic procedures should be performed. No diagnostic work to be done and BSG guidance followed. Upper GI procedures are high risk AGPs and full PPE must be used. | ||||

| Where endoscopy is essential, staff should wear the recommended PPE appropriate for an AGP | 95.6 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Only emergency endoscopy and urgent cancer evaluations should be performed during the pandemic | 90.6 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 0 |

| 7. Consider the diagnosis and risk of COVID-19 in other situations in Emergency General Surgery settings and act accordingly. Presentations with intestinal symptoms occur and COVID-19 may present initially as an apparent post-operative complication. Naso-gastric tube placement may be an aerosol generating procedure (AGP). AGPSs are high risk and full PPE is needed. Consider carrying out in a specified location. | ||||

| Where possible, elective surgery should be conducted in hospitals designated as non-COVID or clean sites | 81.2 | 8.1 | 10.7 | 0 |

The two statements not reaching consensus both related to operative aspects of surgical practice. Firstly, the preferential selection of an open approach rather than laparoscopy was favoured by a majority of 63.4% participants; 20.7% were unsure, and 15.9% disagreed. The second, a more specific point, was the consideration of stoma formation in preference to gastrointestinal anastomoses to reduce the risk of complications, with 64.0% in support, 20.2% unsure, and 15.8% in disagreement.

3.3. RACS document

The content of the RACS document is mapped to consensus statements in Table 4 . Once again consensus was very high with a median consensus of 85.5%, although an outlier led to a wide range (18.7–98.8%). Of 33 statements (de-duplicated from 39), 30 (90.9%) reached consensus agreement.

Table 4.

– Royal Australasian College of Surgeons guidance mapped to Delphi statements.

| Published guidance item |

Agree (%) | Unsure (%) | Disagree (%) | Outside of expertise (n/339) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guidance mapped to Delphi statement(s) | ||||

| Principles 1. Emergency operations will still be necessary for patients with acute, life-threatening conditions. Precautions with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) appropriate to the patient's COVID-19 risk (if known) must be used (see COVID-19 precautions in the operating theatre). | ||||

| PPE level should be determined by (inter)national guidance rather than local policy | 85.4 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 1 |

| Principles 2. Urgent operations (Category 1 in Australia and Non-Deferrable in New Zealand) will be required for patients who will come to harm if delayed more than 4–6 weeks. Depending on the availability of full PPE, a slightly lower level of PPE may be acceptable for those patients who are COVID-19 negative and have a very low risk of having been exposed to the virus so that full PPE is conserved for use with higher risk cases. | ||||

| PPE level should be determined by (inter)national guidance rather than local policy | 85.4 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 1 |

| Clear local plans should be outlined in case supplies of PPE run low or run out | 95.5 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2 |

| All elective work should be postponed at present unless delay substantially affects the prognosis | 91.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1 |

| Principles 3. Where possible, operations for all other patients should be deferred. There is no justification to perform any procedure that can be deferred for six weeks without risk of significant harm to the patient. | ||||

| All elective work should be postponed at present unless delay substantially affects the prognosis | 91.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1 |

| Principles 4. Opt for non-operative management wherever possible. | ||||

| Non-operative management should be preferentially implemented where possible | 85.5 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 0 |

| Trauma injuries should preferentially be managed non-surgically where this appears safe in the short term | 77.8 | 14.9 | 7.3 | 0 |

| Principles 5. Select procedures that minimise the risk of resource consuming complications. For example consider making a stoma rather than an anastomosis in co-morbid patients. | ||||

| Predicted length of stay and impact upon need for ITU should be taken into account in the procedure choice | 90.9 | 7 | 2.1 | 10 |

| Stoma formation should be considered rather than anastomosis to reduce the need for unplanned post-operative critical care for complications | 64 | 15.8 | 20.2 | 42 |

| Endovascular approaches should be used as a bridge to open surgery to expedite discharge where feasible | 78.4 | 18.1 | 3.4 | 107 |

| Principles 6a-d. Outpatients: all referrals should be triaged and appointments deferred whenever possible. | ||||

| All in-person clinic/office work should be cancelled or delivered electronically, unless this substantially affects the prognosis | 93.8 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 1 |

| Principles 7. During this escalating phase of the COVID-19 pandemic it is important that the resources of private hospitals are available to support public hospital services if they become overwhelmed. Private hospital patients who experience complications can consume public hospital resources, especially intensive care. For both these reasons, it is important that no non-urgent elective surgery is undertaken at private hospitals during any period of ‘lockdown’. Private hospitals may be in a position to provide a relief valve for urgent procedures in non-COVID-19 infected patients from the public and the private sectors. Patients and procedures should be carefully selected based on absolute need (i.e. life- threatening conditions only), risk of complications, and safety of staff. | ||||

| All elective work should be postponed at present unless delay substantially affects the prognosis | 91.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1 |

| Precautions 1a-e. High risk - Positive test for COVID-19; Close contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19; International travel within the last 14 days; Sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, fever >38C | ||||

| [Reverse wording] All patients should be considered to be COVID contagious unless proven otherwise during the pandemic | 89.9 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 4 |

| [Reverse wording] Screening questions are a poor way to identify potential patients with COVID | 73.4 | 17.2 | 9.4 | 18 |

| Precautions 2. At least 15% of patients are asymptomatic | ||||

| [No mapped statement available] | ||||

| Precautions 3. Chest x-ray or CT Chest could be considered on clinical grounds | ||||

| The thorax should be included in emergency abdominal CT scans in patients with unknown COVID status | 90.2 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 12 |

| While false negative rates remain substantial, COVID status should be assessed using a CT thorax in patients with unknown COVID status requiring (non-emergent) urgent surgery (e.g. cancer) | 70.8 | 18.7 | 10.5 | 34 |

| Precautions 4. The number of people in the operating theatre should be kept to a minimum | ||||

| Only essential staff should be in the OR for CV19 patients, with no exchange of room staff, except for emergency situations. | 97.9 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1 |

| Precautions 5. Conversation should be kept to a minimum | ||||

| [No mapped statement available] | ||||

| Precautions 6. The operation should be consultant led with no, or one trainee or registrar | ||||

| The most senior person available should perform procedures (e.g. operating/intubating) | 75.1 | 9.5 | 15.4 | 2 |

| Precautions 7. PPE training/sign-off should be undertaken as prescribed by your hospital or jurisdiction i.e. watch recommended videos and attend PPE training session. | ||||

| Every staff member must receive formal training in PPE use before any contact with potential patients with COVID | 98.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0 |

| Precautions 8. Minimum PPE will be recommended by your hospital/jurisdiction. PPE for surgery may include a regular surgical mask for low risk operations or well-fitting face mask (N95 or FF2/3 respirators for high risk cases), eye protection (goggles or visor preferred), full hair cover, impervious gown, and gloves x 2. Also consider impervious foot and ankle cover. | ||||

| PPE level should be determined by (inter)national guidance rather than local policy | 85.4 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 1 |

| The minimum standard for "full" PPE should include: double layers of disposable gloves, water-resistant gown with full length sleeves, eye protection, and N95-99/FFP2-3 mask | 91.9 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 5 |

| Precautions 9. PPE should be removed carefully using a sterile technique, and face and hands washed with soap and water. (PPE training) | ||||

| Teams should practice doffing procedures in advance, following an agreed protocol | 97 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2 |

| Precautions 10. The operation will take longer due to COVID-19 PPE requirements | ||||

| [No mapped statement available] | ||||

| Precautions 11. Consider a second surgeon or team back-up for long complicated operations due to fatigue, dehydration | ||||

| Dual consultant operating can be clinically beneficial in patients with COVID | 59.7 | 26.2 | 14.2 | 14 |

| Precautions 12. You should shower as soon as reasonable and when you get home remove footwear outside, keep footwear separate, take work clothes off, shower and wash clothes separately from family's clothes. | ||||

| Teams should practice doffing procedures in advance, following an agreed protocol | 97 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2 |

| Precautions 13. Particular caution must be taken during Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGP). Appropriate filters and extraction systems should be used to minimise aerosolization. There are many circumstances in the operating theatre where aerosolization can occur, including: | ||||

| [Related but different wording] It is clear which procedures are aerosol generating | 18.7 | 20.8 | 60.5 | 2 |

| Precautions 13a. AGP: Any activity around the oropharynx, including face-mask ventilation, endotracheal or oropharyngeal intubation, extubation, nasogastric intubation. | ||||

| Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal surgery should be avoided where possible | 84 | 16 | 0 | 189 |

| All procedures involving close contact with the face, head and neck be considered high risk for staff in patients with COVID | 95.5 | 3.5 | 1 | 27 |

| Use of any drill in the mouth should be considered an AGP; a rubber dam and high volume suction should be used where possible | 94.1 | 5.9 | 0 | 118 |

| Where endoscopy is essential, staff should wear the recommended PPE appropriate for an AGP | 95.6 | 4.4 | 0 | 23 |

| Precautions 13b. AGP: Energy based haemostasis devices: Diathermy, laser or ultrasonic plume. Only use with suction | ||||

| Filter devices be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy | 88.1 | 9.6 | 2.3 | 36 |

| Electrocautery should be used sparingly and on the lowest possible settings for the desired effect | 76.5 | 17.4 | 6.1 | 29 |

| Use of devices that can promote aerosolization (monopolar electrosurgery, ultrasonic dissectors, advanced bipolar devices) should be minimized. | 80.4 | 16.3 | 3.4 | 13 |

| Monopolar diathermy pencils with attached smoke evacuators should be preferred if electrosurgery is required | 87.6 | 11.8 | 0.6 | 25 |

| Precautions 13c. AGP: Bone saws, drills, burrs, and nibblers. Use guards, screens, suction-exhaust systems | ||||

| Sawing or shaving bone constitutes an aerosol generating procedure | 72.1 | 22.9 | 5 | 99 |

| Precautions 13d. AGP: Laparoscopic venting – use suction, no free or filtered venting | ||||

| Laparoscopy should be considered a coronavirus aerosol generating procedure | 74.5 | 18.6 | 6.9 | 33 |

| Filter devices be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy | 88.1 | 9.6 | 2.3 | 36 |

| Laparoscopic port site incisions should be kept as small as possible | 84.8 | 10.6 | 4.6 | 37 |

| Laparoscopic CO2 insufflation pressure should be kept to a minimum | 82.7 | 15.6 | 1.7 | 38 |

| Precauations 13e. AGP: Wound irrigation – Use a closed system if possible. | ||||

| Maximal level PPE should be worn for any laparotomy in patients with COVID | 93.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 21 |

The three statements not reaching consensus related to procedural and personnel aspects. Similarly to the Joint RCS document, the RACS guidance advocated consideration of stoma formation to minimise the risk of resource-consuming complications. As outlined above, a little under two thirds (64.0%) of participants supported this assertion. The second statement failing to reach consensus described the provision of dual attending/consultant operating. This was mapped to the item recommending allocation of a second consultant or attending in patients with COVID19. A majority of 59.7% participants agreed with dual operating, while 26.2% were unsure, and 14.2% disagreed that it had clinical benefits. The final statement that failed to reach consensus related to participants’ understanding of which procedures were aerosol generating. Fewer than one fifth (18.7%) of participants felt that it was clear which procedures generate aerosols, while 20.5% were unsure and 60.5% felt that it was unclear.

4. Discussion

This study has validated international guidance documents related to surgical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic against broad international expert consensus. The approach engaged 339 worldwide multidisciplinary experts, working in the precise clinical settings of interest, namely the operating rooms in regions affected by COVID-19, making the respondent pool experience-rich. Consensus agreement was evident in 90–93% of statements mapped to the international guidance documents, strongly supporting the initial guidance issued by SAGES/EAES, Joint RCS and RACS.

Consensus statements covered four key domains of practice, as identified in a preliminary systematic review: physical resources, personnel factors, patient factors, and procedure-related factors [6]. The 90% of statements achieving consensus covered all four domains. Within the physical resources domain there was clear support for measures to prevent cross-contamination, such as negative pressure operating rooms and separation of COVID and non-COVID areas. Regarding personnel factors there was a clear priority for protecting the staff, participants agreeing upon the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) according to protocols and restriction to essential personnel only in exposed environments. Patient-related factors reaching consensus included discussion of the additional risk of COVID-19 in consent processes, considering all patients to be contagious, and actively screening patients requiring procedures, including the use of thoracic computerised tomography where required. Supported procedural factors were predominated by statements related to restricting workload to essential urgent and emergent work, e.g. prioritising non-operative management where feasible and safe, and reducing potential aerosolisation, e.g. minimising electrosurgical smoke, using filtration devices.

The small number of mapped statements failing to reach consensus demonstrates the representativeness of the guidance content in relation to wider expert opinion. Non-consensus statements were predominantly within the procedural domain, illustrating uncertainty regarding the operative approach, the actual risk of aerosolisation of procedures such as laparoscopy, and decisions on stoma formation to reduce post-operative complication risks. In addition, one statement each in the physical and personnel domains, reflected uncertainty over the appropriate way to decontaminate surgical equipment, and the benefit or otherwise of dual consultant operating. Although some evidence has emerged regarding aerosolisation and surface stability of the novel coronavirus pathogen [10], how these early findings specifically relate to real-world practice remains far from clear [6,7].

Reliable data influencing surgical practice in the context of COVID-19 remain scarce. Traditional methods of determining best practice underperform in this fast-moving pandemic [6], and real-time sharing of experience and evidence has taken the lead, while research groups [11] and journals [12] have quickly mobilised to catch up. The guidance documents examined herein are notable in their similarity, addressing themes audible in the corridors of surgical units across the world. The haste with which such guidance has been produced and issued is highly commendable, but beyond this, it is clear from this Delphi exercise that those constructing the documents have very effectively represented the views of this large number of international experts in surgical practice.

This study has a number of limitations. Although participants were drawn from all WHO global regions, a majority was based in Europe, so the findings cannot be assumed to be fully representative in the US and Australasia. A single phase Delphi consensus exercise was used, although this compromise permitted the rapid turnaround of this time sensitive project, without reliance upon physical presence from international participants. Two of the three documents examined were issued prior to the consensus process and the documents themselves may have influenced participants’ interaction with consensus statements.

5. Conclusion

This Delphi process achieved broad international participation and has validated 90% of the content of early guidance issued by SAGES/EAES, Joint RCS, and RACS on surgical practice in COVID-19. It has demonstrated a clear and consistent ability among multiple professional bodies to produce internationally representative guidance in the early phase of this pandemic. Areas of contention included the surgical approach, dual consultant operating, the separation of decontamination pathways, and consideration of stoma formation rather than anastomosis. These should be carefully considered by guidance issuers, and represent key targets for urgent research.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required, in accordance with the HRA online tool.

Registration

This project is registered in the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/j8zym/where a protocol can be found. The project is also registered at http://researchregistry.com (UIN: researchregistry5675).

Funding

No funding was received for this project.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Funding sources

Nil.

Research registration Unique Identifying number (UIN)

-

1.

Name of the registry: Research Registry

-

2.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry5675

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/registrationdetails/5ed82f0792120d00159b9d0a/

Author contribution

Beamish AJ – Conceived the study and was involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, and writing, including approval of the final manuscript.

Brown C, Abdelrahman T, Ryan Harper E, Harries RL, Egan RJ were involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, and writing. All approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for its content.

All additional collaborators (JA, TE, LH, OJ, SL, WL, OL, KL, DR, RT and AW) were involved in study design, data collection, and critical revision of the manuscript. All approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for its content.

Guarantor

Andrew J Beamish is guarantor for the work in its entirety.

Data statement

The research data will be available upon request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

WSRI Collaborative is grateful for the support of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS) and this work is conducted as part of the RCS COVID Research Group portfolio. This project is registered in the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/j8zym/(https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/j8zym) and on researchregistry.com: UIN: researchregistry5675.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.015.

Contributor Information

Beamish AJ, Email: beamishaj@gmail.com.

the Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative:

Ansell J, Evans T, Hopkins L, James O, Lewis S, Lewis WG, Luton O, Mellor K, Robinson D, Thomas R, and Williams A

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.COVIDSurg Collaborative Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJS. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng M.H., Boni L., Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann. Surg. 2020:10. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000003924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, European Association for Endoscopic Surgery SAGES and EAES Recommendations Regarding Surgical Response to COVID-19 Crisis. https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/ Accessed: 21st April 2020.

- 4.Association of Surgeons of Great Britain & Ireland Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/joint-guidance-for-surgeons-v2/ Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Royal College of Surgeons of England, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, et al. Updated Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance on COVID-19. Accessed: 21st April 2020.

- 5.Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . Issued 17 April 2020. Guidelines for the Management of Surgical Patients during the Covid 19 Pandemic.https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5137/racs-guidelines-for-the-management-of-surgical-patients-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf Accessed: 21st April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdelrahman T., Ansell J., Brown C., Egan R., Evans T., Ryan Harper E., Harries R.L., Hopkins L., James O., Lewis S., Lewis W.G., Luton O., Mellor K., Powell A.G., Robinson D., Thomas R., Williams A., Beamish A.J. Systematic review of recommended operating room practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJS Open. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs5.50304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelrahman T., Beamish A.J., Brown C., Egan R.J., Evans T., Ryan Harper E., Harries R.L., Hopkins L., James O., Lewis S., Lewis W.G. Surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic: operating room suggestions from an international Delphi process. Br. J. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R., Abdall-Razak A., Crossley E. STROCSS 2019 Guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2019;72:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Registry Research. https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/registrationdetails/5ed82f0792120d00159b9d0a/ Accessed 4th June 2020.

- 10.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., de Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.COVIDSurg Collaborative Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellcome Trust. Press statement: publishers make coronavirus (COVID-19) content freely available and reusable. Issued 16 March 2020. https://wellcome.ac.uk/press-release/publishers-make-coronavirus-covid-19-content-freely-available-and-reusable Available at: Accessed 13 May 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.