Highlights

-

•

In the occurrence of new-onset neurological symptoms in COVID-19 patients, we should suspect an acute ischemic stroke.

-

•

Acute ischaemic stroke continues to be a treatable medical emergency also during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

-

•

Arterial thrombotic events may not only occur in severe cases of COVID-19; but also appear in mild-moderate cases.

-

•

Several pathogeneses may be behind ischemic strokes in COVID-19, in addition to the serious infection coagulopathy.

Keywords: Ischaemic stroke etiologies, COVID, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus disease, Multiple cerebral infarcts, Intrathecal inflammation, Multivessel cerebral infarction

Dear Editor,

COVID-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV2, presents with a broad range of signs and symptoms. Although COVID-19 mainly causes a respiratory syndrome, neurological manifestations have been described in more than a third of patients, both in mild-moderate cases of the infection, as associated or as a complication in severe and critical cases. Anosmia, ageusia, myalgias and headache have been widely described in patients with mild symptoms; while acute cerebrovascular disease, seizures, polyneuritis and encephalopathies have been observed in the most severe cases [1,2].

In this report, we present a patient who was admitted with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 multilobar pneumonia who developed a complex cortical visual deficit consistent with a partial Antons syndrome plus simultagnosia.

A 67-year-old man with a history of hypertension, heavy smoking, and harmful alcohol consumption was brought to the emergency department after being found dazed and confused by his neighbours. He lived alone. His medications included enalapril and acetylsalicylic acid. Upon arrival at the emergency department, he reported a dry cough in the last five days without fever or chills as long as he could recall. On examination, hypoventilation was auscultated in both lungs, basal oxygen saturation was always higher than 93%, and he was afebrile and normotensive. A chest radiograph showed multilobar pneumonia and a nasopharyngeal swab reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) resulted positive for SARS-CoV-2. Consequently, he was admitted to the internal medicine department and treated with a combination of hydroxychloroquine, ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Prophylactic anticoagulation with LMWH and conventional low-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy was also prescribed.

The patient responded positively, without pulmonary complications and with a resolution of the respiratory syndrome both clinically and radiologically. A daily analysis showed peak levels of white cell count in 13.10 × 103μL (lymphocytes 1.9 × 103μL), fibrinogen 543 mg/dL, D-dimer 1777 μg/L, lactate dehydrogenase 341 IU/L, high-sensitivity C reactive protein 3.86 mg/dL, serum ferritin 1107 μg/L; all other parameters were found within normal ranges.

After fifteen days, the neurology service was consulted because the patient remains confused and a significant gait ataxia of undetermined time was detected. Neurological examination showed temporo-spatial disorientation, dysarthria, partial cortical blindness and anosognosia with visual confabulation, optic ataxia, difficulty in visual scanning, simultagnosia, and mild left hemihypoesthesia. An unenhanced brain CT scan was performed showing bilateral parietooccipital and right cerebellar hypoattenuating lesions with areas of cortical hyperattenuating involvement. Differential diagnosis at this point included: subacute ischaemic lesions, posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy, and acute necrotizing encephalopathy; these three entities have been previously observed in the context of a viral infection and recently described in patients with COVID-19 who presented altered mental status and acute cortical visual impairment [3,4].

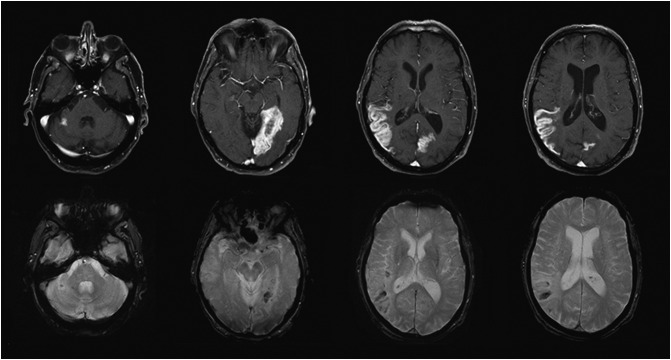

The brain MRI confirmed arterial ischaemic lesions involving the posterior segment of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA), the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA), and a segment of the right superior cerebellar artery (SCA) with a high signal in the long TR sequences with hematic remains of petechial cortical distribution (cortical laminar necrosis). The MR angiography showed normality of the visualised portion of the carotid and vertebrobasilar system, the Willis polygon and the venous sinuses (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI

The top row images show enhanced axial T1 spin-echo fat-saturated sequences. The gyriform enhancement pattern confined to arterial territories suggests subacute ischemia (late phase) in the territory of the right SCA, left PCA and right MCA (left to right).

The bottom row images depict axial T2 gradient echo sequences with blooming artefacts consistent with petechial haemorrhages in the same territory.

An extensive aetiological study of stroke was carried out, which included ECG monitoring for AF screening; transthoracic echocardiogram; supra-aortic and transcranial arterial duplex ultrasound; full-body CT scans; autoimmune serologic testing of the blood (antiphospholipid antibodies included) and serologies of HIV, syphilis, herpes virus and hepatovirus; and a thrombophilia screening test. No remarkable findings were found. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed elevated white blood cell counts (30 cells/mm3, lymphocytes-90%-) and proteins (3141 mg/L) with normal glucose. A Film Array Meningitis/Encephalitis Multiplex PCR Assay, which targets 14 bacteria, viruses, and fungi, was negative, and PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was not performed due to lack of validation for this test in CSF. No other microorganism was detected in cultures. Oligoclonal bands (OCB) analysis showed a type 4 “mirror pattern” reflecting a systemic inflammatory response.

One month after admission, the patient is recovering favourably without new clinical events and the abnormal CSF-findings have normalised after a control lumbar puncture.

We, therefore, present an unusual case of simultaneous multivessel cerebral infarctions, without known extracerebral thrombotic events, in a patient with a moderate COVID-19 who did not develop acute respiratory distress syndrome or disseminated intravascular coagulation. The temporal association with the infectious disease COVID-19, and the lack of other common causes of stroke, lead us to consider that they are associated.

So far, the majority of published cases linking ischaemic stroke to COVID-19 were severe or critical COVID-19 cases with significant hemodynamic and analytical disturbances, especially with D-dimer rates above 5000 ng/mL [5,6].

Moreover, the CSF-analysis, in this case, presented hyperproteinorraquia and lymphocytic pleocytosis greater than expected for an ischaemic stroke. Previous studies carried out in stroke patients showed a variable range of reactive pleocytosis up to 64 Mpt/L cell and nonspecific proteins up to 1507 mg/L in CSF [7]. In cases describing higher concentrations of cells and proteins, such as our case, pathogens causing vascular damage were found. The OCB mirror pattern in CSF (in which identical clones of IgG proteins are present in CSF and serum), suggests that the IgG has entered the central nervous system (CNS) from the systemic circulation, this passive filtration is facilitated by blood-brain barrier damage. This pattern only indicates systemic immune activation but it has been previously observed in cases of systemic viral infections with neurological involvement as cerebral vasculitis (the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis is difficult, in many cases cerebral biopsy is required and it is not always possible to confirm the presence of multiple cerebral artery stenosis in the imaging exam) [8].

It seems clear that patients with severe COVID-19 may suffer an ischaemic stroke or cerebral venous thrombosis because of the hypercoagulability that coincides with the critical illness [9]. But it seems reasonable too to consider that in milder COVID-19 syndromes, other pathophysiological mechanisms may well explain the occurrence of cerebral infarctions. Thereby in other viral infections that have been associated with a higher stroke risk, the vasculitis caused by a direct infection of the cerebral arteries; as well as sustained inflammation triggering instability of atherosclerotic plaque, and a transient thrombophilia have been proposed as the potential mechanisms lead to the cerebral ischaemia [10].

Further studies are needed to clarify the different pathogenic pathways by which COVID-19 may cause strokes and to identify the factors that put COVID patients at higher risk of suffering a stroke.

Informed consent

All patients in the stroke unit have signed an informed consent to collect and use their anonymised data for research purposes.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mao L., Wang M., Chen S., He Q., Chang J., Hong C. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. JAMA Neurol. 10 April 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Ani F., Chehade S., Lazo-Langner A. Thrombosis risk associated with COVID-19 infection. A scoping review. Thromb Res. 27 May 2020;192:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaya Y., Kara S., Akinci C., Kocaman A.S. Transient cortical blindness in COVID-19 pneumonia; a PRES-like syndrome: A case report. J Neurol Sci. 28 April 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116858. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poyiadji N., Shahin G., Noujaim D., Stone M., Patel S., Griffith B. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 3 Mar 2020:201187. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyrouti R., Adams M.E., Benjamin L., Cohen H., Farmer S.F., Yen Goh Y. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 30 April 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodigiani C., Lapichino G., Carenzo L., Cecconi M., Ferrazzi P., Sebastian T. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 23 April 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakapenia A., Barlinn K., Pallesen L.P., Köhler A., Siepmann T., Winzer S. Low diagnostic yield of routine cerebrospinal fluid analysis in juvenile stroke. Front Neurol. 2018;9:694. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro Caldas A., Geraldes R., Neto L., Canhão P., Melo T.P. Central nervous system vasculitis associated with hepatitis C virus infection: a brain MRI-supported diagnosis. J Neurol Sci. 2014;336:152–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D., Kant K.M. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. Jul 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagliano P., Spera A.M., Ascione T., Esposito S. Infections causing stroke or stroke-like syndromes. Infection. 1 April 2020 doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01415-6. Preprint. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]