Abstract

Objective

To determine whether dietary intake of flavonols is associated with Alzheimer dementia.

Methods

The study was conducted among 921 participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), an ongoing community-based, prospective cohort. Participants completed annual neurologic evaluations and dietary assessments using a validated food frequency questionnaire.

Results

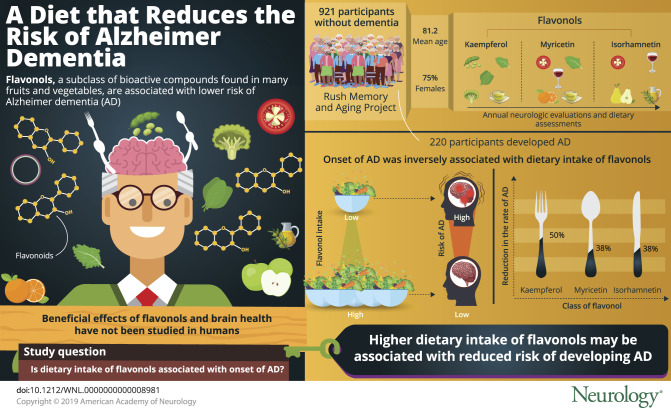

Among 921 MAP participants who initially had no dementia in the analyzed sample, 220 developed Alzheimer dementia. The mean age of the sample was 81.2 years (SD 7.2), with the majority (n = 691, 75%) being female. Participants with the highest intake of total flavonols had higher levels of education and more participation in physical and cognitive activities. In Cox proportional hazards models, dietary intakes of flavonols were inversely associated with incident Alzheimer dementia in models adjusted for age, sex, education, APOE ɛ4, and participation in cognitive and physical activities. Hazard ratios (HRs) for the fifth vs first quintiles of intake were as follows: for total flavonol, 0.52 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33–0.84); for kaempferol, 0.49 (95% CI, 0.31–0.77); for myricetin, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.4–0.97); and for isorhamnetin, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.39–0.98). Quercetin was not associated with Alzheimer dementia (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.43–1.09).

Conclusion

Higher dietary intakes of flavonols may be associated with reduced risk of developing Alzheimer dementia.

Flavonoids are a class of polyphenol representing more than 5,000 bioactive compounds that are found in a variety of fruits and vegetables. A number of flavonoid classes, including flavonols, are known to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.1–4 Two previous studies reported that high levels of flavonoid intakes are associated with lower risk of Alzheimer dementia1,5 but to date, there has not been investigation of the flavonol subclass in humans, even though it is the most abundant flavonoid in foods. Animal studies have demonstrated that dietary flavonols improved memory and learning and decreased severity of Alzheimer disease neuropathology including β-amyloid, tauopathy, and microgliosis.6,7 In this study, we related dietary intakes of flavonols, including kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, and isorhamnetin, to the development of Alzheimer dementia in a large community study.

Methods

Study population

The study was conducted in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), an ongoing (1997–present) community-based cohort of older persons dwelling in Chicago area retirement communities and public housing. Volunteers, who have consented to being participants of MAP, have no known dementia at enrollment and undergo annual clinical neurologic examinations.8 Beginning in 2004, participants were asked to complete a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) during their annual evaluations. As of August 2018, a total of 1,920 older persons were enrolled in MAP, and 1,062 completed a FFQ, of whom 970 had at least 2 clinical evaluations to assess disease incidence. We excluded 36 participants who had a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer dementia at the time of their baseline diet assessment and 13 participants who had missing data on model covariates, leaving 921 participants for the analyses relating flavonol intake to incident Alzheimer dementia.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center approved the study and all participants gave written informed consent.

Data availability

Anonymized data, used for the study, are available through the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center (RADC). Qualified investigators can find information regarding the formal requirements for access to data on the RADC research resource-sharing hub (https://www.radc.rush.edu).

Alzheimer dementia

As described previously,9 the clinical diagnosis of probable Alzheimer dementia was determined at each annual evaluation using a 3-stage process: computerized scoring of performance on 19 cognitive tests and impairment rating for cognitive domains based on a decision tree mimicking clinical judgment; clinical judgment after review of the impairment ratings and clinical information by a neuropsychologist blinded to participant demographics; and final diagnostic classification by an experienced clinician (neurologist, geriatrician, or geriatric nurse practitioner) after review of all available data and examination of the participant. The clinical diagnoses of Alzheimer and other dementias are based on criteria of the joint working group of the Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association.9,10

Dietary assessment

Diet was assessed by a modified version of the Harvard FFQ that was validated for use in an older Chicago population.11 The FFQ ascertains usual frequency of intake of 144 food items over the previous 12 months. Nutrient levels and total energy for each food item were based either on natural portions (e.g., 1 egg) or according to age- and sex-specific serving sizes from national diet surveys. For food levels (grams per serving) of the flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, and isorhamnetin) and total flavonols (calculated as the sum of the 4 individual flavonols), we used the Nutrition Coordinating Center Flavonoid and Proanthocyanidin Provisional Table from University of Minnesota. The majority of values in this table are based on the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3.3 (March 2018) and the USDA Database for the Proanthocyanidin Content of Selected Foods, Release 2.1 (March 2018). Some values, however, are based on journal values from other studies.12 The bioactive contents of the food items were multiplied by the intake frequency and summed across all FFQ items. The top food item contributors to the individual flavonols in our cohort were kale, beans, tea, spinach, and broccoli for kaempferol; tomatoes, kale, apples, and tea for quercetin; tea, wine, kale, oranges, and tomatoes for myricetin; and pears, olive oil, wine, and tomato sauce for isorhamnetin. Energy adjustment of nutrients was computed using the regression residual method.13 Flavonol intakes were based on the first completed valid FFQ, the analytic baseline for each participant in the analyses of incident Alzheimer dementia.

Model covariates

Nondietary model covariates were obtained from structured interview questions and measurements at the clinical evaluation of participants' analytic baseline. Age (in years) was computed from self-reported birth date and date of the baseline cognitive assessment. Education (years) is self-reported years of regular schooling. APOE genotyping was performed using high-throughput sequencing as previously described.14 Participation in cognitively stimulating activities was computed as the average frequency rating, based on a 5-point scale, of different activities (e.g., reading, playing games, writing letters, visiting the library).15 Physical activity (hours per week) was computed from self-reported minutes spent within the previous 2 weeks on 5 activities: walking for exercise, yard work, calisthenics, biking, and water exercise.16 Number of depressive symptoms was assessed by a modified 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale.17 Body mass index (BMI) (weight in kg/height in m2) was computed from measured weight and height and modeled as 2 indicator variables, BMI ≤20 and BMI ≥30, with BMI >20 and <30 as the referent. Hypertension history was determined by self-reported medical diagnosis, measured blood pressure (average of 2 measurements ≥160 mm Hg systolic or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic) or current use of hypertensive medications. Myocardial infarction history was based on self-reported medical diagnosis or use of cardiac glycosides (e.g., lanoxin, digitoxin). Diabetes history was determined by self-reported medical diagnosis or current use of diabetic medications. Information on medications was obtained by interviewer inspection. Clinical diagnosis of stroke was based on clinician review of self-reported history, neurologic examination, and cognitive testing history.18

Statistical analyses

We used Cox proportional hazards models programmed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to investigate the relationships between dietary intakes of the flavonols and the development of Alzheimer dementia. Basic-adjusted models included terms for confounders with the most established scientific evidence for association with Alzheimer dementia: age, sex, education, participation in cognitively stimulating activities, physical activity, and APOE ε4 status.8 Further analyses added covariates to the basic-adjusted models. We analyzed flavonol intakes modeled in quintiles and as a single ordinal variable in which intake levels within each quintile were scored the median quintile value. We report the p value of the ordinal variable as a measure of linear trend. Effect modification of flavonol associations by various covariates was investigated by including a multiplicative term between the flavonol categorical trend variable and the potential effect modifier in the basic-adjusted model. Statistically significant interactions were further investigated by reanalyzing the basic-adjusted models within strata of the effect modifier. Throughout, statistical significance corresponds to p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Among the 921 MAP participants who initially did not have dementia in the analyzed sample, 220 developed Alzheimer dementia (39.06 cases per 1,000 person-years) during the follow-up period (mean follow-up 6.1 years; SD 3.1). The mean age of the sample was 81.2 years (SD 7.2), with the majority (n = 691, 75%) being female (table 1). Participants with the highest intake of total flavonols had higher levels of education and were more likely to participate in physical and cognitive activities (table 1). Spearman correlation coefficients among dietary intakes of the individual flavonols were low to moderate (range of r = 0.14 to r = 0.51), as were the correlations of flavonols to high-quality diet scores (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH], Mediterranean, and Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay [MIND]) (r = 0.13–0.48).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics by quintile of 921 Rush Memory and Aging Project participants

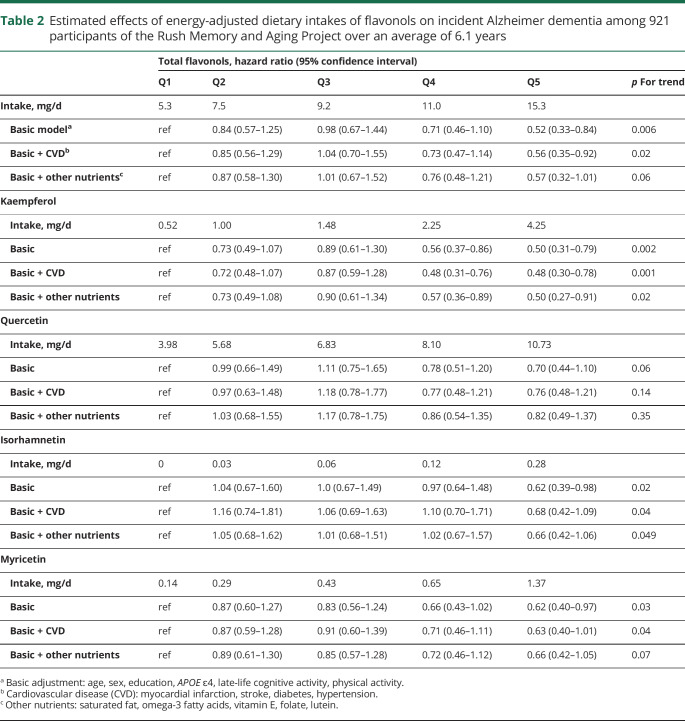

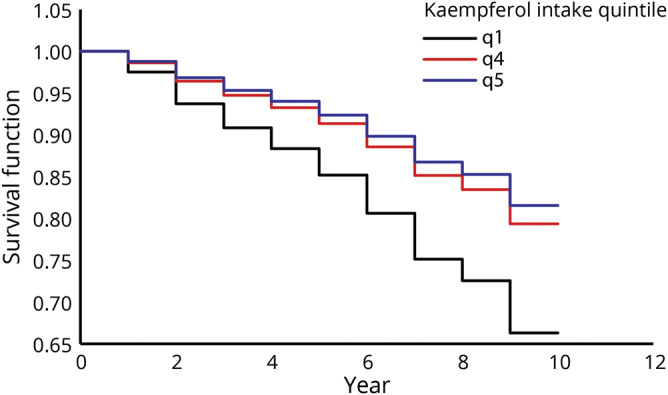

Dietary intakes of total flavonols (figure 1) and the flavonol constituents were statistically significantly associated with reduced risk of Alzheimer dementia (table 2). Participants in the highest vs lowest quintiles of total flavonol intake had a 48% lower rate of developing AD in the basic-adjusted model including the covariates age, sex, education, APOE ɛ4, late-life cognitive activity, and physical activity (table 2). Among the flavonol constituents, isorhamnetin, kaempferol (figure 2), and myricetin were each associated with a reduction in the rate of incident AD, with reductions of 38%, 50%, and 38%, respectively, for persons in the fifth vs first quintiles of intake (table 2). Dietary intake of quercetin was not associated with incident AD (hazard ratio [HR], 0.70; confidence interval [CI], 0.44–1.10). The tests for linear trend were statistically significant for total flavonols and all subclasses except for quercetin (p = 0.06).

Figure 1. Estimated survival function of Alzheimer dementia by quintiles 1, 4, and 5 of dietary intake of total flavonols over time.

Table 2.

Estimated effects of energy-adjusted dietary intakes of flavonols on incident Alzheimer dementia among 921 participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project over an average of 6.1 years

Figure 2. Estimated survival function of Alzheimer dementia by quintiles 1, 4, and 5 of dietary intake of kaempferol over time.

We next investigated whether the flavonol associations with AD could be attributed to their potential protective effects on cardiovascular conditions by adding terms for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke to the basic model. There were no substantial changes in the results (table 2). We then explored whether intakes of other nutrients related to AD, including vitamin E, saturated fat, folate, lutein, and omega-3 fatty acids, could account for the results. However, there were no material changes in the estimated effects (table 2).

In secondary analyses, we further adjusted for BMI and depression, covariates that may be both risk factors and clinical sequelae of AD.8 The effect estimates for flavonols in these models were either materially unchanged or more protective. The association of total flavonols with Alzheimer dementia was statistically significant; the HR (95% CI) for Q5 vs Q1 of total flavonol intake was 0.49 (0.30–0.79) (p = 0.003). Effect estimates for the flavonol constituents were as follows: kaempferol (HR Q5 vs Q1, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.33–0.83; p = 0.005), quercetin (HR Q5 vs Q1, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38–0.97; p = 0.02), isorhamnetin (HR Q5 vs Q1, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34–0.88; p = 0.008), and myricetin (HR Q5 vs Q1, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39–0.98; p = 0.02).

In subsequent analyses, we investigated independent effects of the flavonols by simultaneously modeling all 4 (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, and isorhamnetin) in the basic-adjusted model. In these analyses, only kaempferol (p for trend = 0.03) had an independent association with AD. The other flavonols were not statistically significant: isorhamnetin (p for trend = 0.053), quercetin (p for trend = 0.83), and myricetin (p for trend = 0.35).

To investigate the extent to which the observed protective associations of flavonol intake may be biased by preclinical effects of AD on dietary behavior, we reanalyzed the data after excluding cases (n = 29) that were diagnosed during the first year of follow-up. In these analyses, the findings were unchanged for intakes of total flavonol (Q5 vs Q1: HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.34–0.94; p for trend = 0.03), kaempferol (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.29–0.80; p = 0.007), isorhamnetin (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.40–1.10; p = 0.04), and myricetin (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.33–0.89; p = 0.01). However, the findings for quercetin were not statistically significant (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.42–1.12; p = 0.11). In further analyses that removed the first 2 years of follow-up (n = 65), the flavonol associations were no longer statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05, but strongly suggestive: total flavonol (p-trend = 0.051), kaempferol (p-trend = 0.051), quercetin (p-trend = 0.07), myricetin (p-trend = 0.08), and isorhamnetin (p-trend = 0.13). We investigated to what extent baseline mild cognitive impairment could bias the protective association of dietary flavonols and Alzheimer dementia. We reran our basic model after excluding those with MCI at baseline (n = 217). The statistical significance remained for total flavonol (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.20–0.84; p = 0.02) and kaempferol (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.27–0.99; p = 0.045). The association with quercetin (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26–1.02; p = 0.03) was highly suggestive while myricetin (p = 0.38), and isorhamnetin (p = 0.23) became nonsignificant.

We explored potential effect modification in the observed associations by age (≤80, >80), sex, education (≤12 years, >12 years), and APOE ɛ4 status in the basic-adjusted model. The only statistically significant modification of effect was by sex, such that the association of total flavonol intake was stronger in men (Q5 vs Q1: HR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.08–0.76) than in women (Q5 vs Q1: HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.35–0.99).

Discussion

In this community-based prospective study of older persons, we found evidence that higher flavonol intake through food sources, and kaempferol and isorhamnetin in particular, may be protective against the development of Alzheimer dementia. The associations were independent of many diet and lifestyle factors and cardiovascular-related conditions.

To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the relation of flavonol intake with incident Alzheimer dementia. Two previous studies reported inverse associations with incident AD and intake of the larger class of total flavonoids, of which flavonols are a subclass.1,5 In a previous study, we found that kaempferol intake, which is abundant in leafy green vegetables, was associated with slower rate of cognitive decline.19 The Nurses' Health Study observed higher global cognitive scores over 6 years among women with higher flavonoid intakes.20 The PAQUID study (Personnes Agées Quid) reported an association between total flavonoid intake and cognitive decline over 10 years of follow-up.21 Earlier studies have demonstrated an association of healthy diet patterns with Alzheimer dementia and cognitive decline.22,23 Although the correlations of these diets with flavonol intake, as mentioned above, are mild to moderate, these studies lend support to the prior temporal effect of dietary exposure on Alzheimer dementia.

We focused on flavonols for these analyses due to the fact that the biochemical composition of this flavonoid subclass likely makes them particularly effective antioxidants.2,3 The catechol structure, found in polyphenolic compounds and abundant in flavonols, has the capability to act as a radical ion scavenger. This action can take place in the plasma, and the gut, where flavonols can limit reactive oxygen species formation.3 In animal models, treatment with kaempferol and myricetin significantly reduced the level of oxidative stress via increased activity of superoxide dismutase in the hippocampus and improved learning and memory capabilities.6 Another model of transgenic mice with AD-like pathology found that 3-month treatment with a myricetin derivative, dihydromyricetin, improved cognition and reduced the accumulation of soluble Aβ40 in the hippocampus and both soluble and insoluble Aβ42 in the cortex.24 In mice that were injected with Aβ25-35 to induce an Alzheimer dementia–like disease, the mice that were then supplemented with oral intake of quercetin exhibited improved cognitive function and memory and inhibited lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide in the brain vs the Aβ25-35 control group.25 Another animal model of triple transgenic AD mice demonstrated that mice treated with quercetin vs the vehicle-treated mice had significantly lower β-amyloidosis and tauopathy and decreased astrogliosis and microgliosis in several parts of the brain. Quercetin supplementation also improved cognitive function as measured by memory and learning.7 Animal models have demonstrated that flavonoids may act directly on neurons and glia through a signal transduction cascade. There is also an indirect effect via interaction with the cerebral vascularity as well as the blood–brain barrier.4,26 Furthermore, in vitro studies have demonstrated the capability of some flavonoid constituents and metabolites to cross the blood–brain barrier.27

The study has a number of strengths that lend to the validity of the findings. These include the prospective design among community-dwelling residents, structured annual neurologic assessments, standardized diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer dementia, a long follow-up period (up to 12 years), use of a comprehensive, validated diet assessment tool, and annual assessment of the major lifestyle and other factors associated with dementia. A limitation of the study is its observational study design, and thus the possibility of residual confounding by measured and unmeasured factors. The FFQ is a self-reported tool and may introduce recall bias. Given that our population sample was almost exclusively white, highly educated, and altruistically motivated (organ donation is a requirement for participation), the findings cannot be generalized to nonwhite, low-educated, or nonvolunteer populations. In addition, there is the possibility that dietary changes in participants with subclinical AD biased the observed estimates of effect. It is difficult to determine whether this could lead to underestimation or overestimation of the observed associations. However, supportive findings from long follow-up studies of flavonoid intake and cognitive decline20,21 would appear to lessen this alternative explanation of our findings.

Our findings suggest that dietary intake of flavonols may reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer dementia. Confirmation of these findings is warranted through other longitudinal epidemiologic studies and clinical trials in addition to further elucidation of the biologic mechanisms. Although there is more work to be done, the associations that we observed are promising and deserve further study.

Acknowledgment

Thomas M. Holland, MD, and Martha Clare Morris, ScD, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center study staff and the Memory and Aging Project participants.

Glossary

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- DASH

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaire

- HR

hazard ratio

- MAP

Rush Memory and Aging Project

- RADC

Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center

- USDA

US Department of Agriculture

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

Supported by the NIH, National Institute on Aging grant RF1AG051641 (PIs: Martha Clare Morris, ScD; Sarah L. Booth, PhD) and grant R01AG017917 (PI: David A. Bennett, MD); and partially supported by the USDA Agricultural Research Service under Cooperative Agreement No. 58-1950-7-707. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the US Department of Agriculture.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2002;287:3223–3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youdim KA, Spencer JPE, Schroeter H, Rice-Evans C. Dietary flavonoids as potential neuroprotectants. Biol Chem 2002;383:503–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietta P. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J Nat Prod 2000;63:1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youdim KA, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. Flavonoids and the brain: interactions at the blood–brain barrier and their physiological effects on the central nervous system. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;37:1683–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commenges D, Scotet V, Renaud S, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Barberger-Gateau P, Dartigues JF. Intake of flavonoids and risk of dementia. Eur J Epidemiol 2000;16:357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lei Y, Chen J, Zhang W, et al. In vivo investigation on the potential of galangin, kaempferol and myricetin for protection of D-galactose-induced cognitive impairment. Food Chem 2012;135:2702–2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maria SGA, Ignacio MMJ, Ramírez-Pineda Jose R, Marisol LR, Edison O, Patricia CGG. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates Alzheimer's disease pathology and protects cognitive and emotional function in aged triple transgenic Alzheimer's disease model mice. Neuropharmacology 2015;93:134–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:646–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology 2006;27:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris MC, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire by cognition in an older biracial sample. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:1213–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flavonoid and Proanthocyanidin Provisional Table. University of Minnesota Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Kelly JF, Bennett DA. Apolipoprotein E e4 allele is associated with more rapid motor decline in older persons. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2005;11:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Physical activity and motor decline in older persons. Muscle Nerve 2007;35:354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 1993;5:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett DA. Secular trends in stroke incidence and survival, and the occurrence of dementia. Stroke 2006;37:1144–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris MC, Wang Y, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Dawson-Hughes B, Booth SL. Nutrients and bioactives in green leafy vegetables and cognitive decline: prospective study. Neurology 2017;90:e214–e222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devore EE, Kang JH, Breteler MMB, Grodstein F. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann Neurol 2012;72:135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letenneur L, Proust-Lima C, Le Gouge A, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Flavonoid intake and cognitive decline over a 10-year period. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1364–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dement 2015;11:1007–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, et al. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimer Dement 2015;11:1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang J, Kerstin Lindemeyer A, Shen Y, et al. Dihydromyricetin ameliorates behavioral deficits and reverses neuropathology of transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Res 2014;39:1171–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Lee J, Lee S, Cho EJ. Quercetin and quercetin-3-b-D-glucoside improve cognitive and memory function in Alzheimer's disease mouse. Appl Biol Chem 2016;59:721–728. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaeger BN, Parylak SL, Gage FH. Mechanisms of dietary flavonoid action in neuronal function and neuroinflammation. Mol Aspects Med 2018;61:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youdim KA, Dobbie MS, Kuhnle G, Proteggente AR, Abbott NJ, Rice-Evans C. Interaction between flavonoids and the blood–brain barrier: in vitro studies. J Neurochem 2003;85:180–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data, used for the study, are available through the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center (RADC). Qualified investigators can find information regarding the formal requirements for access to data on the RADC research resource-sharing hub (https://www.radc.rush.edu).