Capsule summary:

Treatment of high-risk infants with HDM SLIT during early life resulted in a trend for reduction in asthma rates mid-childhood. This may be a viable preventative therapy for childhood asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, Immunotherapy, Prevention, Childhood, Randomized controlled trial, Atopy

To the Editor,

Asthma has increased in recent decades worldwide with prevalence up to 15%, in the US, the direct cost of uncontrolled asthma is estimated at over $300 billion during next 20 years (1). Allergic sensitization in early life, particularly multiple sensitization, carries the greatest risk for later asthma (2) and therefore primary prevention must target infancy, prior to sensitization occurring. Evidence has emerged that exposure to a high dose of allergen early in life can drive the developing immune system towards a state of tolerance (3).

One such strong immune stimulus is house dust mite (HDM), a potent, prevalent allergen. The Mite Allergy Prevention Study (MAPS) was the first trial investigating HDM sub-lingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for primary prevention of atopy in non-sensitized infants (4, 5). In this proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, one year of HDM SLIT led to a significant reduction in any sensitization compared to placebo. The treatment was safe and acceptable to families. We report the results of assessment at age 6.5 years, five years after cessation of immunotherapy.

The study was carried out as described in the Supplementary Material. Briefly, 111 infants, aged 5 months and at high risk of atopy (≥2 first-degree atopic relatives) but with negative skin-prick tests (SPT) were recruited and randomized to either oral HDM or saline placebo twice daily for 12 months. At 6 years participants underwent assessment for asthma, a priori primary outcome. Validated questionnaires were used for wheeze, as well as rhinitis, food allergy and eczema. They underwent SPT to nine allergens and an extensive respiratory assessment including spirometry with reversibility, exhaled nitric oxide and methacholine bronchial hyper-responsiveness. This information was used to diagnose definite or likely asthma by an adjudication committee of three blinded, experienced, independent clinicians (see Supplementary Material for definitions). An observational birth cohort “Immune Tolerance in Early Childhood” (ITEC) of high risk infants was also recruited at the same time as MAPS. These infants were similar to the MAPS participants at baseline, and assessed identically at age 6. An intention to treat analysis was undertaken using Stata software, version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, USA) and GraphPad Prism v7 (San Diego, USA).

Of the 111 infants originally randomized into study (Fig S2), 41 participants in the SLIT (71·9%) and 44 participants in the placebo group (81·5%) completed the assessment at age six. The groups were well-balanced, although the placebo group had a longer duration of breastfeeding and less pet exposure at home compared to the SLIT group at baseline (Table S1). The ITEC participants were similar to the MAPS placebo group except for a shorter breastfeeding duration and younger age at baseline (Table S2).

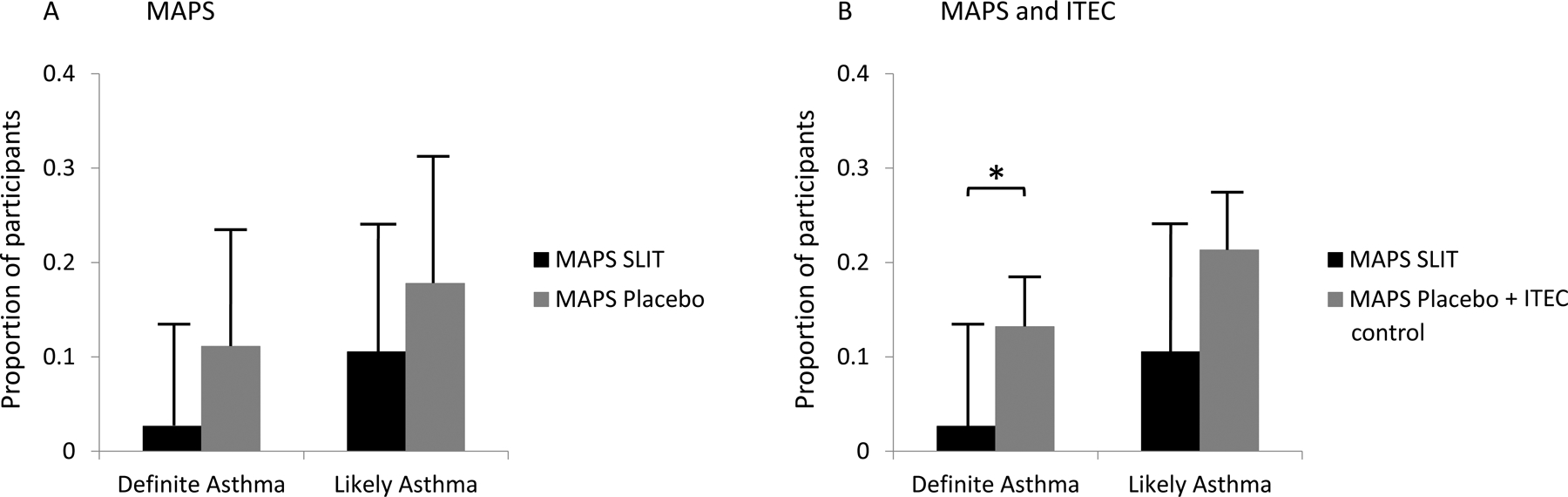

A trend for lower rates of asthma (primary outcome) was noted in the SLIT group. For definite asthma, there was 1 case (2·9%) in the SLIT and 5 (13·5%) in the placebo groups (10·6% difference, 95% CI 23·0%, −1·8%, p = 0·11). For likely asthma, 4 (10·8%) participants in the SLIT and 8 (20·0%) in the placebo were affected (p = 0·27) (Figure 1A). There was no difference between the groups in lung function, FeNO and BHR (Supplementary Material), or other atopic outcomes (Table S4).

Figure 1:

Comparison of definite asthma and likely asthma (definite + probable) diagnosis between: A MAPS SLIT and MAPS placebo groups; B MAPS SLIT and MAPS placebo + ITEC control groups. Bars represent proportion of participants within group, with 95% CI bars. *= p <0·05.

In a secondary analysis, incorporating ITEC cohort with MAPS placebo group, to increase power, significantly lower rates of definite asthma were seen in the SLIT group (1 case [2·9%]) compared to 26 [16·8%]), [13·8% difference, 95% CI 22·0%, 5·7%, p = 0·04]) (figure 1B), and a trend for less “likely asthma” was noted (13·6% difference, 95% CI 26·2%, −2·3 %, p = 0·07). Removing from analysis the 12 ITEC participants sensitized at baseline did not alter the results (Table S6).

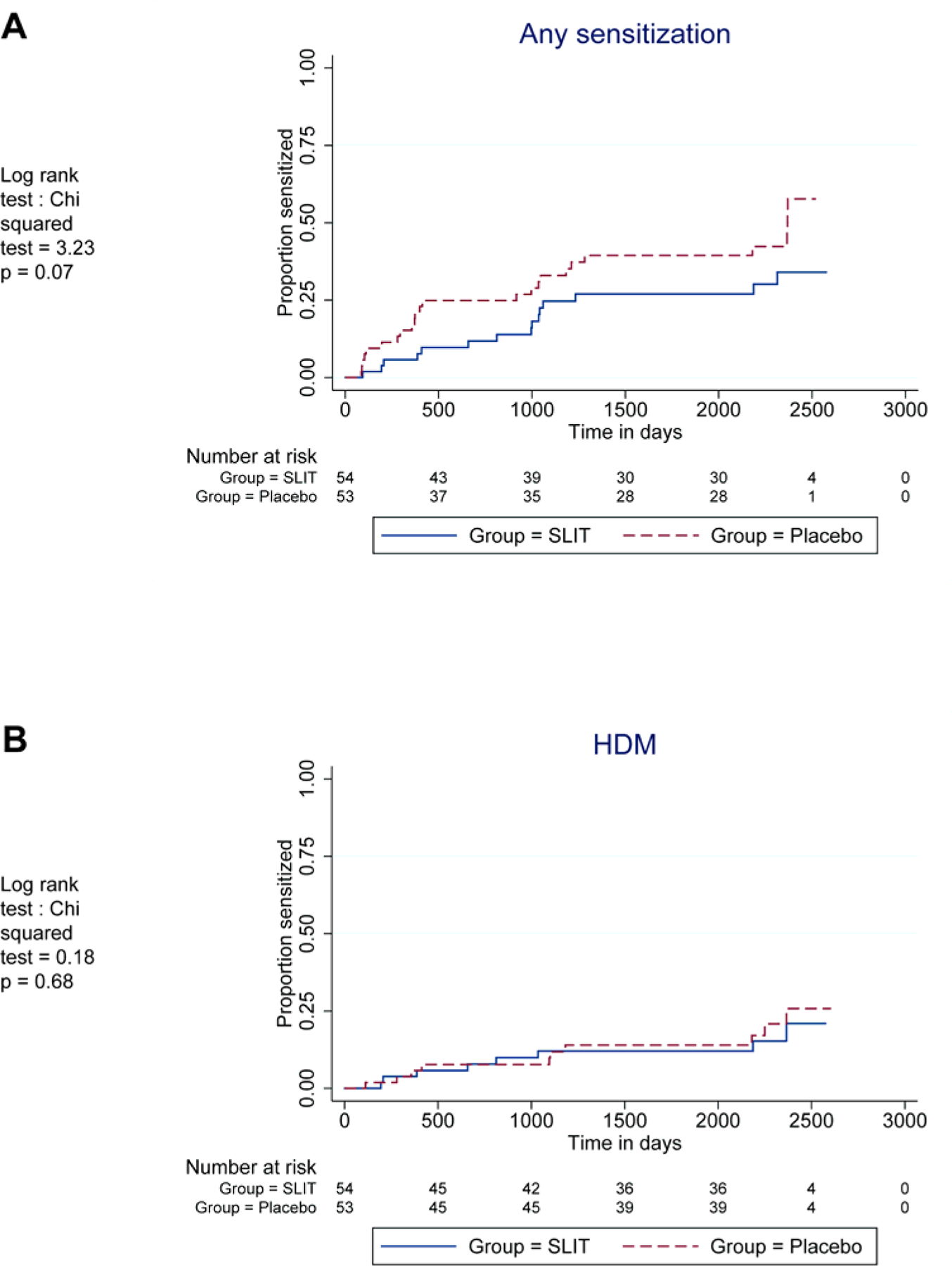

For the secondary outcome of any allergic sensitization a trend was maintained for reduced sensitization in the SLIT group compared to placebo (p= 0·07) (Figure 2A), in a time-to-event analysis. At age six, 15 (27·8%) children were sensitized in the SLIT compared to 24 (45·4%) in the placebo group, (18·2% difference [95% CI, 35·1% to −1·8%, p= 0·06]). No difference was seen in rates of sensitization to HDM alone (Figure 2B, Table S5).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meyer plot comparing SLIT and placebo participants’ cumulative sensitization to any common allergen (A) or HDM alone (B) over the entire study follow-up period up.

We have mirrored the early food allergen exposure inducing tolerance approach with HDM for respiratory allergies. HDM allergen was selected as it is a potent immune reactor modulating the developing immune system through allergenic, endotoxin and enzymatic effects with a bystander effect on other allergens (6)..

A recent meta-analysis on the use of AIT as primary immunoprophylaxis was inconclusive (7). This was ascribed to the limited body of evidence of the short term-effect of AIT on prevention, with no published RCTs investigating the long-term preventive effects of AIT. Previous studies have failed to demonstrate a role for the use of immunotherapy in the prevention of asthma and sensitization in young children (8, 9). However, the populations studied were older, and already sensitized to at least one allergen.

Our study was a small, single-centre proof-of-concept study and therefore has a number of limitations. Sample size was small, and the study was only powered to assess correct ordering of sensitization. It may also have been more effective to use a larger allergen dose and longer duration of treatment, although the allergen dose used has been shown to induce immunological response. Nonetheless, we established safety, feasibility and preliminary proof of efficacy of SLIT in this young population.

To increase power of analysis a comparison was made between SLIT group and the placebo group combined with ITEC participants as additional controls. Both MAPS and ITEC participants were recruited in parallel from the same population and the two cohorts were highly comparable, except breast feeding was more frequent in the MAPS placebo group than ITEC cohort. As SLIT participants were also breast fed less than the MAPS placebo group, combining the MAPS placebo and ITEC cohort equalized breastfeeding rates.

In summary, this remains the only double-blind, placebo-controlled study investigating primary prevention of asthma and atopy using allergen immunotherapy, demonstrating that early life administration of HDM SLIT may reduce childhood asthma. The results seen when the larger ITEC study is incorporated into the analysis gives credence to this conclusion. Further, adequately powered studies are now required to assess the efficacy of this approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their families and the research team at both study sites, Drs Connett, Legg and Woolf for evaluating asthma data, Southampton National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre and National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases, US (R01AI121426-01).

Sources of funding:

This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, UK, through its funding of Southampton NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, and National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases, US (R01AI121426-01). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing the report.

Conflict of Interest:

G. Roberts has received research support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and National Institute of Health (NIH); he has received lecture fees from ALK-Abello and is a member of the ALK-Abello advisory board, and has a patent held by the university. Dr. Arshad reports grants from NIHR, UK; grants from National Institute of Health, USA, non-financial support and other from ALK-Abello, Denmark. In addition, Dr. Arshad has a patent for use of house dust mite allergen immunotherapy for primary prevention of asthma and atopy pending. Dr. Vijayanand reports grants from the NIH during the conduct of the study.

Abbreviations

- SLIT

sub-lingual immunotherapy

- HDM

House dust mite

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Yaghoubi M, Adibi A, Safari A, FitzGerald JM, Sadatsafavi M. The Projected Economic and Health Burden of Uncontrolled Asthma in the United States. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019;200(9):1102–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Niggemann B, Gruber C, Wahn U. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2006;368(9537):763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372(9):803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zolkipli Z, Roberts G, Cornelius V, Clayton B, Pearson S, Michaelis L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of primary prevention of atopy using house dust mite allergen oral immunotherapy in early childhood. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;136(6):1541–7.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alviani C, Roberts G, Moyses H, Pearson S, Larsson M, Zolkipli Z, et al. Follow-up, 18 months off house dust mite immunotherapy, of a randomized controlled study on the primary prevention of atopy. Allergy. 2019;74(7):1406–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregory LG, Lloyd CM. Orchestrating house dust mite-associated allergy in the lung. Trends in Immunology. 2011;32(9):402–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kristiansen M, Dhami S, Netuveli G, Halken S, Muraro A, Roberts G, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for the prevention of allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2017;28(1):18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holt PG, Sly PD, Sampson HA, Robinson P, Loh R, Lowenstein H, et al. Prophylactic use of sublingual allergen immunotherapy in high-risk children: a pilot study. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;132(4):991–3.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szepfalusi Z, Bannert C, Ronceray L, Mayer E, Hassler M, Wissmann E, et al. Preventive sublingual immunotherapy in preschool children: first evidence for safety and pro-tolerogenic effects. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2014;25(8):788–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.