Abstract

Background

Primary central nervous system tumors (PCNST) among adolescents and young adults (AYA, 15–39 y) have rarely been reported. We present a nationwide report of PCNST histologically confirmed in the French AYA population between 2008 and 2013.

Methods

Patients were identified through the French Brain Tumor Database (FBTDB), a national dataset that includes prospectively all histologically confirmed cases of PCNST in France. Patients aged 15 to 39 years with histologically confirmed PCNST diagnosed between 2008 and 2013 were included. For each of the 143 histological subtypes of PCNST, crude rates, sex, surgery, and age distribution were provided. To enable international comparisons, age-standardized incidence rates were adjusted to the world-standard, European, and USA populations.

Results

For 6 years, 9661 PCNST (males/females: 4701/4960) were histologically confirmed in the French AYA population. The overall crude rate was 8.15 per 100 000 person-years. Overall, age-standardized incidence rates were (per 100 000 person-years, population of reference: world/Europe/USA): 7.64/8.07/8.21, respectively. Among patients aged 15–24 years, the crude rate was 5.13 per 100 000. Among patients aged 25–39 years, the crude rate was 10.10 per 100 000. Age-standardized incidence rates were reported for each of the 143 histological subtypes. Moreover, for each histological subtype, data were detailed by sex, age, type of surgery (surgical resection or biopsy), and cryopreserved samples.

Conclusion

These data represent an exhaustive report of all histologically confirmed cases of PCNST with their frequency and distribution in the French AYA population in 2008–2013. For the first time in this age group, complete histological subtypes and rare tumor identification are detailed.

Keywords: adolescent and young adult, brain tumor, epidemiology, neuro-oncology, neuropathology, neurosurgery

Key Points.

1. For the first time, incidence data for rare tumors are presented at a national level.

2. Almost all malignant primary CNS tumors have a histologically confirmed diagnosis.

3. Histological grouping distributions are close to those observed in the United States.

Importance of the Study.

Reports focused on epidemiology of primary central nervous system tumors among adolescents and young adults (15–39 y) are very rare. Only the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) has provided a comprehensive report including frequency and distribution of primary central nervous system tumors in adolescents and young adults, but it did not detail all rare tumor subtypes. We reference CBTRUS for US comparisons unless otherwise stated. Here, all subtypes are detailed, and age-standardized incidence rates were adjusted to the world-standard, European, and United States populations to allow for comparisons. In addition, our methodology based on the inclusion of histologically proven cases ensures that analyses presented in this study are based on the highest quality data available from collection practices in France. This study offers many perspectives in the fields of clinical epidemiology and research.

Primary central nervous system tumors (PCNST) found in adolescents and young adults (AYA) are a distinct group of tumors that pose challenges for diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Cancers that occur in this age group have specific biological, epidemiological, and therapeutic issues.1,2 In this age group, PCNST are among the most common cancers,3–6 and deaths due to PCNST are the third most common cause of cancer death in the United States.3 Recent analysis has reported that while cancer survival has been improving overall, the AYA population has not experienced the same increases in survival.4 For a long time, this specific population has been neglected by both pediatric and adult oncologists, with a lack of specific clinical trials and treatment guidelines.1,7,8 Even the definition of the AYA age group is not consensual: while age ranges from 15 to 24 years and from 15 to 29 years have been previously used, the US National Institutes of Health established a wider range including patients aged from 15 to 39 years. Furthermore, the most commonly diagnosed PCNST histologies in AYA are different than those in younger or older age groups.5,9–11 In addition, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 classification,12,13 there are 143 histological subtypes in PCNST, with different causes, prognostic factors, and treatments. Epidemiological data on PCNST are poor with few national registries, as the declaration is not mandatory in many countries. Among existing registries, the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS),10 the Canadian Cancer Registry,14 the Austrian Brain Tumor Registry,15 and the registries from Scandinavia,16 England,17 and other regional registries18 provide important data on the PCNST epidemiology, although they do not provide extensive data for all WHO subtypes and rarely report in-depth analysis concerning the AYA population.5

In this report based on systematic histologically confirmed PCNST cases in France from 2008 to 2013, we aimed at providing exhaustive descriptive epidemiological data and incidence rates for all histological subtypes of PCNST in the AYA population (15–39 y). Considering that no study has previously provided an accurate epidemiological assessment of all PCNST subtypes (including rare histological subtypes) in the AYA population, this report could help to better understand their impact on the population, to identify subpopulation at risk, and to serve as a reference for searchers and clinicians investigating new therapies.

Patients and Methods

Data Source and Patients Selection

The French Brain Tumor Database (FBTDB) identified and recorded all patients (eg, AYA) with newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed PCNST since 2006 in France, and prospectively collected initial data. FBTDB is one of the largest clinical databases for brain tumors in Europe, and its methodology was previously published.19–23 In summary, FBTDB is based on a network of all neurosurgeons, pathologists, and neuro-oncologists involved in PCNST, in collaboration with all societies focused on PCNST. Data are collected from two sources. First, a data sheet, which is available in all operating rooms where neurosurgery is performed, is filled out by both the neurosurgeon and the pathologist. Second, a listing of all cases analyzed by each pathology department is collected annually, to ensure the exhaustiveness of the collection.19–23

Here, we conducted a nationwide population-based study. All AYA (15–39 y) with newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed PCNST between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2013 in metropolitan France were included (metropolitan France includes mainland France and nearby islands in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea and excludes overseas territories). Tumors were described using the WHO 2007 classification.12 Note: pituitary tumors do not belong to the PCNST according to the WHO classification, but are included in a few PCNST registries such as the CBTRUS and were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: secondary tumors of the CNS (metastases), duplicate records for recurrent disease (in that case, data from the first surgery were recorded if within the inclusion period), and patients from abroad or French overseas departments.

Main Measures

Because some tumors share the same International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) code, FBTDB collects and records the name of each histological type and subtype.19–23 Here, incidence rate, sex distribution, type of surgery (resection or biopsy), and number of cryopreserved samples were provided for each histological subtype according to the ICD-O third revision PCNST classification.12 Note, the ICD-O-3 codes found in the 2007 WHO classification were adopted by SNOMED (the systematized nomenclature of medicine issued by the College of American Pathologists). The list of the included codes is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical Analysis

Crude incidence rates (CR) and age-standardized incidence rates (ASR) per 100 000 person-years were calculated for each histological subtype of PCNST. CR corresponded to the number of new cases occurring in each considered population (metropolitan France) during the period 2008–2013; it was expressed as the number of cases per 100 000 person-years. To enable international comparisons, ASR truncated the age groups to 15–24, 25–39, and 15–39. ASR is the theoretical rate that would have occurred if the observed age-specific rates applied in appropriate portion of the reference population.24 ASR were computed on a direct standardization model with Europe (ASReu), United States (ASRus), and worldwide (ASRww) standard populations as references. The statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software and GraphPad Prism 7.0.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by French legislation (CCTIRS 10.548, CNIL 911013) and by all the French societies involved in neuro-oncology: the Société Française de Neurochirurgie and the Club de Neuro-Oncologie from the Société Française de Neurochirurgie, the Société Française de Neuropathologie, and the Association des Neuro-Oncologues d’Expression Française.

Results

Overall Descriptive Characteristics, Crude Rates, and Age-Standardized Incidence Rates

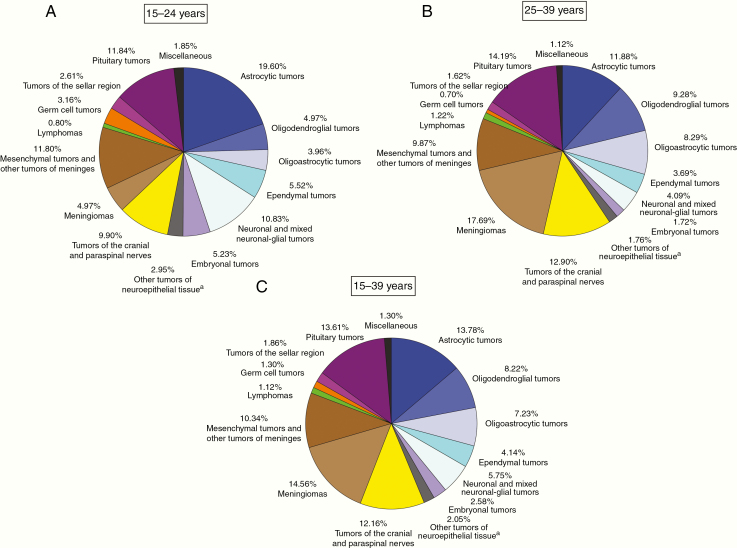

Between 2008 and 2013, 9661 PCNST were histologically confirmed in the French AYA population (15–39 y). Among all diagnosed PCNST, 4701 were in males and 4960 were in females. The characteristics of all the cases—including the number of cases, the type of surgery, the presence of cryopreserved samples, the ASR adjusted on world-standard population (ASRww), Europe population (ASReu), and US population (ASRus) in the 15–39 years of age population—are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The main results are summarized in Table 1, which shows the case distribution by histology, sex, annual average, and ASRus. The overall CR was 8.15 per 100 000 person-years (ASRww, ASReu, and ASRus were respectively 7.64, 8.07, and 8.21 per 100 000). The overall CR in the 15–24 year old population was 5.13 per 100 000 person-years (ASRww, ASReu, and ASRus were respectively 5.11, 5.12, and 5.11 per 100 000). The overall CR in the 25–39 year old population was 10.10 per 100 000 person-years (ASRww, ASReu, and ASRus were respectively 9.79, 10.03, and 10.20 per 100 000). Complete data for 15–24 and 25–39 year old populations are provided in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. The distribution of PCNST by histological groupings in the 15–24 year old, 25–39 year old, and 15–39 year old populations are provided in Fig. 1. Tumors of neuroepithelial tissue were the most represented histological subgroup in the 15–39 year old population, accounting for about 43.7% of all PCNST (CR: 3.57 per 100 000 person-years).

Table 1.

Case distribution by histology, sex, annual average, and age-standardized incidence rates to the US population in AYA (15–39 y) (period of inclusion: 2008–2013, 6-y total = 9661)

| Histology | Male | Female | Annual Average | ASRus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumors of Neuroepithelial Tissue | 2417 | 1808 | 704.2 | 3.59 |

| Gliomas | 1879 | 1425 | 550.7 | 2.81 |

| Glioma, NOS | 42 | 39 | 13.5 | 0.07 |

| Astrocytic tumors | 763 | 568 | 221.8 | 1.13 |

| Astrocytoma, NOS | 55 | 37 | 15.3 | 0.08 |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | 192 | 145 | 56.2 | 0.29 |

| Pilomyxoid astrocytoma | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | 15 | 21 | 6.0 | 0.03 |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | 22 | 26 | 8.0 | 0.04 |

| Fibrillary astrocytoma | 37 | 19 | 9.3 | 0.05 |

| Gemistocytic astrocytoma | 16 | 10 | 4.3 | 0.02 |

| Protoplasmic astrocytoma | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.00 |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 59 | 45 | 17.3 | 0.09 |

| Glioblastoma | 328 | 239 | 94.5 | 0.49 |

| Giant cell glioblastoma | 17 | 15 | 5.3 | 0.03 |

| Gliosarcoma | 6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Gliomatosis cerebri (a) | 12 | 6 | 3.0 | 0.02 |

| Oligodendroglial tumors | 436 | 358 | 132.3 | 0.67 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 306 | 236 | 90.3 | 0.46 |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | 130 | 122 | 42.0 | 0.21 |

| Oligoastrocytic tumors | 385 | 313 | 116.3 | 0.59 |

| Oligoastrocytic tumors, NOS | 54 | 36 | 15.0 | 0.08 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 204 | 181 | 64.2 | 0.33 |

| Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma | 127 | 96 | 37.2 | 0.19 |

| Ependymal tumors | 253 | 147 | 66.7 | 0.34 |

| Subependymoma | 20 | 7 | 4.5 | 0.02 |

| Myxopapillary ependymoma | 66 | 35 | 16.8 | 0.09 |

| Ependymoma, NOS | 114 | 72 | 31.0 | 0.16 |

| Cellular ependymoma | 5 | 7 | 2.0 | 0.01 |

| Papillary ependymoma | 5 | 2 | 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Clear cell ependymoma | 10 | 3 | 2.2 | 0.01 |

| Tanicytic ependymoma | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Anaplastic ependymoma | 32 | 19 | 8.5 | 0.04 |

| Choroid plexus tumors | 23 | 30 | 8.8 | 0.04 |

| Choroid plexus papilloma | 21 | 25 | 7.7 | 0.04 |

| Atypical choroid plexus papilloma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Choroid plexus carcinoma | 2 | 5 | 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Other neuroepithelial tumors | 4 | 10 | 2.3 | 0.01 |

| Astroblastoma | 1 | 4 | 0.8 | 0.00 |

| Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Angiocentric glioma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Esthesioneuroblastoma | 3 | 4 | 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Neuronal and mixed neuronal-glial tumors | 316 | 239 | 92,5 | 0.47 |

| Dysplastic gangliocytoma of cerebellum (Lhermitte-Duclos) | 2 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma | 6 | 5 | 1.8 | 0.01 |

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor | 69 | 54 | 20.5 | 0.10 |

| Gangliocytoma | 10 | 6 | 2.7 | 0.01 |

| Ganglioglioma | 160 | 102 | 43.7 | 0.22 |

| Anaplastic ganglioglioma | 10 | 9 | 3.2 | 0.02 |

| Central neurocytoma | 48 | 50 | 16.3 | 0.08 |

| Extraventricular neurocytoma | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Cerebellar liponeurocytoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Papillary glioneuronal tumor | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor of the fourth ventricle | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Paraganglioma | 7 | 8 | 2.5 | 0.01 |

| Tumors of the pineal region | 23 | 27 | 8.3 | 0.04 |

| Pinealoma, NOS | 7 | 6 | 2.2 | 0.01 |

| Pineocytoma | 7 | 5 | 2.0 | 0.01 |

| Pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation | 1 | 9 | 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Pineoblastoma | 6 | 6 | 2.0 | 0.01 |

| Papillary tumor of the pineal region | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Embryonal tumors | 172 | 77 | 41.5 | 0.21 |

| Medulloblastoma, NOS | 112 | 52 | 27.3 | 0.14 |

| Desmoplastic medulloblastoma | 29 | 7 | 6.0 | 0.03 |

| Medulloblastoma with extensive nodularity | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Anaplastic medulloblastoma | 7 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.01 |

| Large cell medulloblastoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumor | 20 | 10 | 5.0 | 0.03 |

| CNS neuroblastoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| CNS ganglioneuroblastoma | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Medulloepithelioma | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Ependymoblastoma | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor | 2 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Tumors of the Cranial and Paraspinal Nerves | 599 | 576 | 195.8 | 1.00 |

| Schwannoma (neurilemoma, neurinoma) | 492 | 479 | 161.8 | 0.83 |

| Schwannoma (neurofibromatosis) | 18 | 11 | 4.8 | 0.02 |

| Cellular schwannoma | 8 | 4 | 2.0 | 0.01 |

| Plexiform schwannoma | 1 | 4 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| Melanotic schwannoma | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Neurofibroma, NOS | 36 | 42 | 13.0 | 0.07 |

| Plexiform neurofibroma | 5 | 5 | 1.7 | 0.00 |

| Neurofibroma (neurofibromatosis) | 22 | 14 | 6.0 | 0.03 |

| Perineurioma, NOS | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Perineurioma, malignant | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) | 12 | 10 | 3.7 | 0.02 |

| Epithelioid MPNST | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| MPNST with mesenchymal differentiation | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.00 |

| Melanotic MPNST | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| MPNST with glandular differentiation | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Tumors of Meninges | 857 | 1549 | 401.0 | 2.06 |

| Tumors of meningothelial cells | 375 | 1032 | 234.5 | 1.21 |

| Meningioma, NOS | 87 | 285 | 62.0 | 0.32 |

| Meningothelial meningioma | 108 | 323 | 71.8 | 0.37 |

| Fibrous (fibroblastic) meningioma | 26 | 78 | 17.3 | 0.09 |

| Transitional (mixed) meningioma | 39 | 154 | 32.2 | 0.17 |

| Psammomatous meningioma | 10 | 19 | 4.8 | 0.03 |

| Angiomatous meningioma | 6 | 6 | 2.0 | 0.01 |

| Rare variety meningioma, NOS | 12 | 25 | 6.2 | 0.03 |

| Microcystic meningioma | 1 | 12 | 2.2 | 0.01 |

| Secretory meningioma | 0 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Clear cell meningioma | 0 | 4 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Chordoid meningioma | 2 | 8 | 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Rhabdoid meningioma | 3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Metaplastic meningioma | 3 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.01 |

| Atypical meningioma | 70 | 98 | 28.0 | 0.14 |

| Papillary meningioma | 3 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Anaplastic meningioma | 5 | 13 | 3.0 | 0.02 |

| Mesenchymal tumors | 352 | 368 | 120.0 | 0.61 |

| Benign mesenchymal tumor, NOS | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Lipoma | 18 | 10 | 4.7 | 0.02 |

| Angiolipoma | 3 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.01 |

| Hibernoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Liposarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | 1 | 13 | 2.3 | 0.01 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Leiomyoma | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Rhabdomyoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Chondroma | 2 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 7 | 12 | 3.2 | 0.02 |

| Osteoma | 8 | 20 | 4.7 | 0.02 |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 3 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Osteochondroma | 2 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Hemangioma | 284 | 281 | 94.2 | 0.48 |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Hemangiopericytoma | 5 | 11 | 2.7 | 0.01 |

| Anaplastic hemangiopericytoma | 10 | 4 | 2.3 | 0.01 |

| Angiosarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Ewing’s sarcoma-PNET | 9 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.01 |

| Primary melanocytic lesions | 14 | 7 | 3.5 | 0.02 |

| Diffuse melanocytosis | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Melanocytoma | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Malignant melanoma | 13 | 7 | 3.3 | 0.02 |

| Meningeal melanomatosis | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Other neoplasms related to the meninges | 116 | 142 | 43.0 | 0.22 |

| Hemangioblastoma | 116 | 142 | 43.0 | 0.22 |

| Lymphomas and Hematopoietic Neoplasms | 67 | 41 | 18.0 | 0.09 |

| Malignant lymphoma, NOS | 65 | 40 | 17.5 | 0.09 |

| Plasmacytoma | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Granulocytic sarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Germ Cell Tumors | 104 | 22 | 21.0 | 0.11 |

| Germinoma | 71 | 12 | 13.8 | 0.07 |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Yolk sac tumor | 3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Choriocarcinoma | 3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Teratoma, NOS | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Teratoma mature | 14 | 5 | 3.2 | 0.02 |

| Immature germ cell tumors, NOS | 4 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.00 |

| Teratoma immature | 2 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Teratoma with malignant transformation | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Mixed germ cell tumor | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Tumors of the Sellar Region | 107 | 73 | 30.0 | 0.15 |

| Craniopharyngioma | 97 | 65 | 27.0 | 0.14 |

| Adamantinous craniopharyngioma | 7 | 7 | 2.3 | 0.01 |

| Papillary craniopharyngioma | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Granular cell tumor | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Pituicytoma | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| Spindle cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Pituitary Tumors | 486 | 829 | 219.2 | 1.11 |

| Pituitary adenoma, typical | 204 | 280 | 80.7 | 0.41 |

| Non-secreting pituitary adenoma | 32 | 30 | 10.3 | 0.05 |

| Pituitary adenoma with functional activity-secreting | 15 | 15 | 5.0 | 0.02 |

| Adenoma lactant | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Follicle stimulating hormone–secreting pituitary adenoma | 43 | 36 | 13.2 | 0.07 |

| Prolactinoma | 74 | 244 | 53.0 | 0.26 |

| Pituitary adenoma with multiple hormonal secretions | 13 | 18 | 5.2 | 0.03 |

| Growth hormone–secreting pituitary adenoma | 52 | 48 | 16.7 | 0.08 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone–secreting pituitary adenoma | 3 | 5 | 1.3 | 0.01 |

| Adrenocorticotropin hormone–secreting pituitary adenoma | 49 | 148 | 32.8 | 0.17 |

| Malignant tumor of the pituitary gland (neuroendocrine carcinoma) | 0 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.00 |

| Miscellaneous | 64 | 62 | 21.0 | 0.11 |

| Chordoma | 13 | 15 | 4.7 | 0.02 |

| Malignant NOS/suspicion | 8 | 8 | 2.7 | 0.01 |

| Other | 43 | 39 | 13.7 | 0.07 |

| Total | 4701 | 4960 | 1610.2 | 8.21 |

Age-standardized incidence rates were adjusted to the United States populations (ASRus) to allow for comparisons. ASR are per 100 000 person-years and rounded to two decimal places. NOS, not otherwise specified.

(a) The diagnosis of gliomatosis cerebri is probably much underestimated because the histological diagnosis is most often based on a single histological specimen.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of PCNST by histology and age groups. (A) 15–24 years (6-year total = 2373), (B) 25–39 years (6-year total = 7288), (C) 15–39 years (6-year total = 9661). Reported percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. a: includes choroid plexus tumors and tumors of the pineal region (Supplementary Table 1), astroblastoma, chordoid glioma of the third ventricle, angiocentric glioma, and esthesioneuroblastoma.

Incidence Rates by Sex and Histology

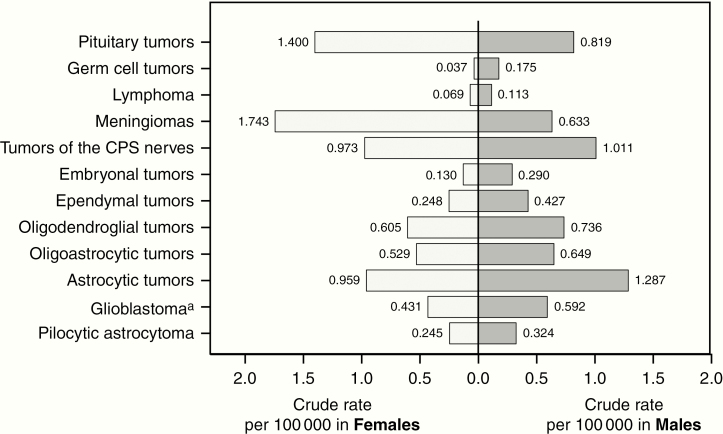

Overall, the incidence of PCNST in females (CR: 8.38 per 100 000 person-years) was higher than that in males (CR: 7.93 per 100 000 person-years). This difference by sex tended to increase with aging, partly due to the increasing incidence of tumors of the meningothelial cells in older females (CR: 0.23 per 100,000 person-years in females age 15–24 y and CR: 2.69 per 100 000 person-years in females age 25–39 y). CR by sex for selected histology groupings in AYA are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Crude rates of PCNST by sex for selected histology groupings and histologies. CPS: Cranial and paraspinal. a: includes ICD-O-3 histology codes 9440/3, 9441/3, and 9442/3.

Incidence Rates by Age and Histology

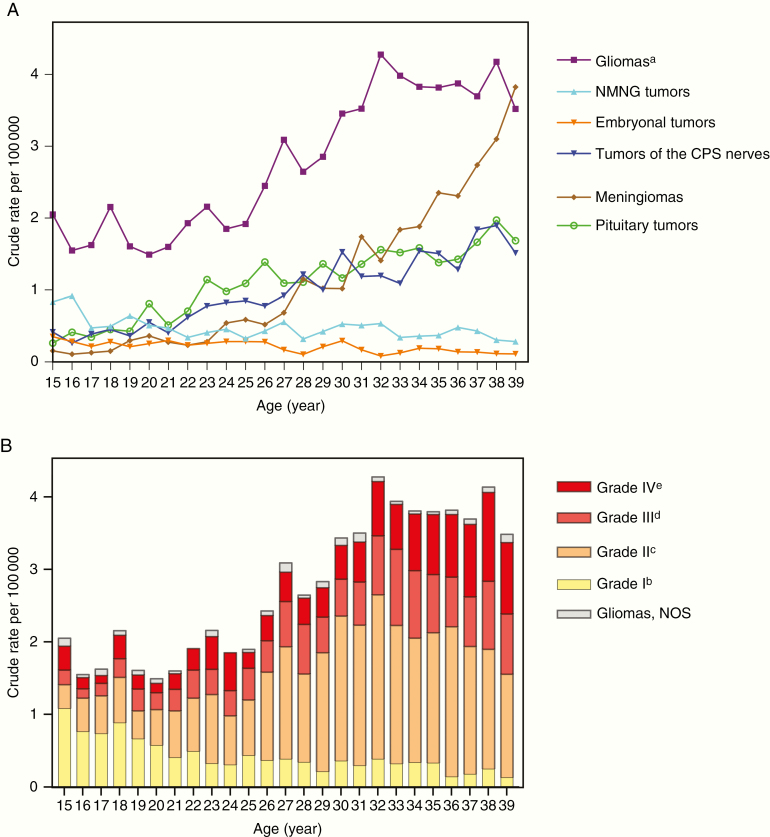

The most common histological category among all patients age 15–39 years was glioma (CR in persons aged 15 y was 2.05 per 100 000 person-years, and CR in persons aged 38 y was 4.18 per 100 000 person-years), except at the age of 39 years, where the incidence of meningiomas exceeded the incidence of gliomas (3.82 per 100 000 person-years vs 3.52 per 100 000 person-years). CR for principal histological subtypes by age are presented in Fig. 3A. CR for gliomas depending on malignancy grade (WHO 2007) by age are presented in Fig. 3B.

Fig. 3.

(A) Crude rates of PCNST by age for selected histology groupings and (B) crude rates of gliomas by age and distribution by grade of malignancy (WHO 2007).

NMNG: neuronal and mixed neuronal-glial. CPS: Cranial and paraspinal. NOS: not otherwise specified.

a: includes astrocytic tumors, oligoastrocytic tumors, oligodendroglial tumors, ependymal tumors, and gliomas not otherwise specified (NOS)

b: includes ICD-O-3 histology codes 9421/1, 9384/1, 9383/1, 9394/1

c: includes ICD-O-3 histology codes 9425/3, 9424/3, 9400/3, 9420/3, 9411/3, 9410/3, 9450/3, 9382/3 (excluding anaplastic oligoastrocytoma), 9391/3, 9392/3

d: includes ICD-O-3 histology codes 9401/3, 9451/3, 9382/3 (excluding non-anaplastic oligoastrocytoma), 9392/3

e: includes ICD-O-3 histology codes 9440/3, 9441/3, 9442/3

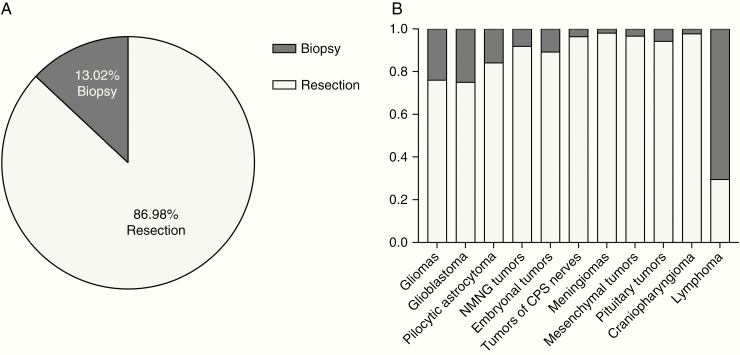

Surgical Technique: Resection and Biopsy

Surgical resection was performed in 86.98% of patients for whom data were available (ie, 7814 patients; Supplementary Table 1). Fractions of biopsies and resections depending on histological subtypes are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of biopsies and surgical resections (N = 7814). (A) Overall distribution among PCNST, and (B) distribution of biopsies and resections for selected histology groupings and histologies. Reported percent/fraction may not add up to 100%/1.0 due to rounding.

Discussion

For the first time, exhaustive data for all histologically confirmed cases of PCNST in the French AYA population are reported. Due to the huge heterogeneity of these tumors, data about many rare subtypes of PCNST are also provided.

Comparison to Other AYA Cancers

PCNST are the third most common tumors in AYA in the United States (10.43 per 100 000 person-years, which is close to our results reporting 8.18 per 100 000 person-years), with only breast cancers (21.22 per 100 000 person-years) and thyroid cancers (10.84 per 100 000 person-years) occurring more frequently.5 Other French cancer registries used for the surveillance of cancers in AYA (15–24 y) reported PCNST as the fifth most common cancer, following lymphomas and hematopoietic neoplasms, gonadal germ cell tumors, thyroid carcinomas, and melanomas,25 although these results included only 11 French departments (out of 97) and did not include AYA aged over 24 years. In addition, germ cell tumors of the central nervous system were not included in the PCNST subcategory.

Differences and Similarities with Existing Registries for PCNST in the AYA Population

For most tumor categories, the patterns by sex and age reflected those found in the literature.

When adjusting French ASR to the United States population, the frequency of PCNST described in the French AYA population is close to the US AYA population5: for example, ASRus per 100 000 persons were 0.29 for pilocytic astrocytoma (0.28 in the US), 0.49 for glioblastoma (0.48 in the US), 0.34 for ependymal tumors (0.37 in the US), 1.00 for tumors of cranial and paraspinal nerves (0.91 in the US), 2.06 for tumors of meninges (1.98 in the US), 0.11 for germ cell tumors (0.12 in the US), and 0.14 for craniopharyngioma (0.13 in the US).

In our study, overall PCNST ASRus was 8.21 per 100 000, which is slightly lower than the CBTRUS reports (10.43 per 100 000). This overall difference may be explained by a lower incidence of pituitary tumors in our report (ASRus was 1.11 per 100 000 vs 3.10 per 100 000 in the US), which may be related to the fact that most tumors of the pituitary do not undergo surgery and remained underdiagnosed through our histologically based registry. In addition, we found a lower frequency for meningiomas (ASRus was 1.21 vs 1.74 per 100 000 in the US) but a higher incidence rate for mesenchymal tumors (ASRus was 0.61 vs 0.07 per 100 000 in the US) with a similar overall incidence rate in the tumors of meninges subcategory (ASRus was 2.06 vs 1.98 per 100 000 in the US). In addition, the incidence rates in oligodendroglial tumors were higher in the French AYA population than in the US AYA population (ASRus was 0.46 for oligodendrogliomas and 0.21 for anaplastic oligodendrogliomas vs respectively 0.29 and 0.08 per 100 000 in the US). This difference is probably related to the Daumas-Duport grading system,26 whose influence was strong among the French pathologist community.

Comparison with data from other developed regions is difficult because of the different definitions used for AYA, the use of different classification systems for PCNST (eg, inclusion or exclusion of non-malignant tumors), and reports from confined areas without nationwide coverage or with an important heterogeneity regarding the registration regulations and procedures. For example, in a Canadian nationwide study (2009–2013),14 most histological categories in malignant tumors reported in the 20–34 year old range had incidences close to our results, although non-malignant tumors were not included in this study. Other registries from different regions and countries studying overall cancer incidences and survival rates in AYA were reported, although most of these reports did not provide detailed incidences by histologies and ASR allowing accurate international comparison. Available reports seem to indicate a lower incidence rate of PCNST, such as the Italian registries (2003–2008)27 in AYA aged 15–19 years (incidence rates per 100 000 were 2.8 for males and 3.0 for females, including non-malignant PCNST but excluding embryonal tumors); the Shanghai registries (2003–2005)28 in AYA aged 15–49 years (incidence rates per 100 000 were 3.3 for males and 4.3 for females); the Southern and Eastern Europe registries (1990–2014)29 in AYA aged 15–39 years including only malignant tumors (overall incidence rate was 2.81 per 100 000 with an important heterogeneity depending on registries and period of registration); and the Netherlands registry (1989–2009)30 in AYA aged 15–29 years where European standardized rates per 100 000 are presented for astrocytoma (1.04 in males, 0.81 in females), ependymoma (0.18 in males and females), and medulloblastoma (0.23 in males, 0.16 in females).

Resection, Biopsy, and Cryopreservation

The percentage of resection versus biopsy from 7814 patients was higher in the AYA population than in the general population (86.98% vs 79.1%, based on a previous study using the FBTDB results from 2006–201122). These numbers certainly reflect a more radical surgical management in AYA than in the overall population. In addition, rates of cryopreservation were higher in this study than rates observed in the overall population (34.6% vs 23.4%22).

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is that the FBTDB does not collect cases without histology confirmation, which causes a selection bias. In some selected histologically confirmed subtypes, ASR reported in this study may be lower than ASR observed in other registries, including medically treated pituitary tumors, non-operated meningiomas, non-biopsied brainstem gliomas, and medically treated germ cell tumors. Nonetheless, even if our methods do not allow an exact estimation of incidence rates in PCNST, the methodology of the FBTDB ensures exhaustiveness in the recording of all histologically confirmed PCNST in metropolitan France. Such histological population-based studies are essential to validate prognostic factors and are representative of the overall oncological care management requiring histological confirmation for treatment purpose.

Another limitation is that in France multiple histopathological reviews are not yet performed systematically unless patients are enrolled in clinical trials or in a national biological database. Nonetheless, histological diagnosis was always made by experienced neuropathologists; more than 90% of these neuropathologists work in public academic centers. Moreover, recently French pathologists, in accordance with the French National Cancer Institute, have decided to perform a pathologic review for all rare PCNST, as part of a national project entitled “RENOCLIP.”

Analysis of molecular markers is increasingly performed for PCNST, and is now part of the diagnosis for some histological subtypes (ie, diffuse astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas). Unfortunately, our study was conducted prior to 2016, and data were based on the WHO 2007 classification, so it did not include the analysis of molecular markers. However, the current data based on the 2007 WHO classification will serve as a reference for future epidemiological studies using the new classification.

Perspectives

The findings of this study provide an exhaustive resource for epidemiologists, clinicians, and translational researchers in a field of neuro-oncology that has been poorly investigated so far.

While the entire spectrum of PCNST can be observed at any age, the study of the transition of tumor types in AYA is a key point to understand the tumorigenesis and the underlying differences in the biology of tumors in this age group relative to younger and older patients.

These data also emphasize the persistence and decrease over age of certain tumors often considered as “pediatric” (eg, pilocytic astrocytomas, germ cell tumors, embryonal tumors) during the AYA years (Figures 1 and 3). These patterns suggest that practical management of some tumors in adulthood may involve both pediatric and adult neuro-oncologists.

This report could also help to better understand the impact of PCNST on the AYA population, to identify subpopulations at risk, and to serve as a reference for researchers investigating specific treatment guidelines, the majority of which are derived from younger or older patient populations and often produce underwhelming results.4

Conclusion

For the first time, these data based on 9661 histologically confirmed tumors described the frequency and distribution of PCNST in the French AYA population (15–39 y). Histological subtypes for all PCNST including rare tumors were presented by age, sex, surgery, and cryopreservation. Moreover, for all histological subtypes, age-standardized incidence rates were adjusted to the worldwide, European, and United States populations to allow for comparisons. In addition, the reported distribution of PCNST in France reflected an expected pattern based on the previously CBTRUS report regarding AYA in the United States. The exhaustiveness of histological population-based studies allows many perspectives in the fields of clinical epidemiology and research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all neuropathologists, neurosurgeons, and neuro-oncologists who helped to record all cases of PCNST. All collaborators are listed in Supplementary Text 1.

With the participation of the Société Française de Neurochirurgie (SFNC) and the Club Neuro-Oncologie of the Société Française de Neurochirurgie (CNO-SFNC), the Société Française de Neuropathologie (SFNP), and the Association des Neuro-Oncologues d’Expression Française (ANOCEF).

Funding

This work was conducted with the financial support, as grants, of Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, Associations pour la Recherche sur les Tumeurs Cérébrales (ARTC-Nord, ARTC-Sud), Sophysa Laboratory, Département de l’Hérault, and Groupe de Neuro-Oncologie du Languedoc-Roussillon.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authorship statement

SN, SZ, LB, FBa, FBe, HMD, BT contributed to data collection and analysis. LB conceived and designed the analysis. FBe conducted statistical analysis. All authors helped in interpreting the findings and were involved in the management of the database. SN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed toward subsequent revisions and approved the submitted manuscript.

References

- 1. Bleyer A, Barr R, Hayes-Lattin B, Thomas D, Ellis C, Anderson B; Biology and Clinical Trials Subgroups of the US National Cancer Institute Progress Review Group in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology The distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(4):288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kieran MW, Walker D, Frappaz D, Prados M. Brain tumors: from childhood through adolescence into adulthood. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4783–4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2012 Incidence, WONDER Online Database. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewis DR, Seibel NL, Smith AW, Stedman MR. Adolescent and young adult cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014(49):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, de Blank PM, et al. American Brain Tumor Association adolescent and young adult primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(suppl 1):i1–i50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trama A, Botta L, Foschi R, et al. ; EUROCARE-5 Working Group Survival of European adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer in 2000-07: population-based data from EUROCARE-5. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frappaz D, Sunyach MP, Le Rhun E, et al. ; au nom de l’ANOCEF, GO-AJA, de la SFCE Adolescent and young adults (AYAs) brain tumor national web conference. On behalf of ANOCEF, GO-AJA and SFCE societies. Bull Cancer. 2016;103(12):1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Desandes E, Guissou S, Chastagner P, Lacour B. Incidence and survival of children with central nervous system primitive tumors in the French National Registry of Childhood Solid Tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(7):975–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(suppl_4):iv1–iv86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ostrom QT, de Blank PM, Kruchko C, et al. Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation infant and childhood primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2015;16(Suppl 10):x1–x36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walker EV, Davis FG; CBTR founding affiliates Malignant primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in Canada from 2009 to 2013. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(3):360–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wöhrer A, Waldhör T, Heinzl H, et al. The Austrian Brain Tumour Registry: a cooperative way to establish a population-based brain tumour registry. J Neurooncol. 2009;95(3):401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deltour I, Johansen C, Auvinen A, Feychting M, Klaeboe L, Schüz J. Time trends in brain tumor incidence rates in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, 1974–2003. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(24):1721–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arora RS, Alston RD, Eden TO, et al. Are reported increases in incidence of primary CNS tumours real? An analysis of longitudinal trends in England, 1979–2003. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(9):1607–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baldi I, Gruber A, Alioum A, et al. ; Gironde TSNC Registry Group Descriptive epidemiology of CNS tumors in France: results from the Gironde Registry for the period 2000-2007. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(12):1370–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bauchet L, Rigau V, Mathieu-Daudé H, et al. French brain tumor data bank: methodology and first results on 10,000 cases. J Neurooncol. 2007;84(2):189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rigau V, Zouaoui S, Mathieu-Daudé H, et al. ; Société Française de Neuropathologie (SFNP), Société Française de Neurochirurgie (SFNC); Club de Neuro-Oncologie of the Société Française de Neurochirurgie (CNO-SFNC); Association des Neuro-Oncologues d’Expression Française (ANOCEF) French brain tumor database: 5-year histological results on 25 756 cases. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(6):633–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zouaoui S, Rigau V, Mathieu-Daudé H, et al. ; Société française de neurochirurgie (SFNC) et le Club de neuro-oncologie de la SFNC; Société française de neuropathologie (SFNP); Association des neuro-oncologues d’expression française (ANOCEF) French brain tumor database: general results on 40,000 cases, main current applications and future prospects. Neurochirurgie. 2012;58(1):4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Darlix A, Zouaoui S, Rigau V, et al. Epidemiology for primary brain tumors: a nationwide population-based study. J Neurooncol. 2017;131(3):525–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fabbro-Peray P, Zouaoui S, Darlix A, et al. Association of patterns of care, prognostic factors, and use of radiotherapy-temozolomide therapy with survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a French national population-based study. J Neurooncol. 2019;142(1):91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyle P, Parkin DM. Statistical methods for registries. In: Jensen OM, Parkin DM, MacLennan R, Muir CS, Skeet RG, ed. Cancer registration: principles and methods. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;( 95):129–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Desandes E, Clavel J, Lacour B, Grosclaude P, Brugières L. La surveillance des cancers de l’adolescent et du jeune adulte en France. Bull Epidemiol Hebd, INVS. 2013;49–50:497–500. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daumas-Duport C, Beuvon F, Varlet P, Fallet-Bianco C. Gliomas: WHO and Sainte-Anne Hospital classifications. Ann Pathol. 2000;20(5):413–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. AIRTUM Working Group, CCM, AIEOP Working Group. Italian cancer figures, report 2012: cancer in children and adolescents. Epidemiol Prev. 2013;37(1 Suppl 1):1–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu QJ, Vogtmann E, Zhang W, et al. Cancer incidence among adolescents and young adults in urban Shanghai, 1973–2005. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Georgakis MK, Panagopoulou P, Papathoma P, et al. Central nervous system tumours among adolescents and young adults (15–39 years) in Southern and Eastern Europe: registration improvements reveal higher incidence rates compared to the US. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aben KK, van Gaal C, van Gils NA, van der Graaf WT, Zielhuis GA. Cancer in adolescents and young adults (15–29 years): a population-based study in the Netherlands 1989–2009. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(7):922–933. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.