1. Introduction

In the COVID-19 epidemic context, because of the shortage of diagnostic RT-PCR tests (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction), the French public health strategy as of April 7, 2020 is to obtain as many positive tests as possible to be able to follow the epidemic evolution. Thus, the use of tests has been restricted. They are performed with nasopharyngeal samples, which sensitivity is moderate (70%) [1]. In real conditions though, can the prescription relevance and the sampling quality influence these results?

2. Methodology

This cross-sectional study was based on COVID-19 RT-PCR tests performed at the Dynabio laboratory, a group of five laboratories in Rillieux-la-Pape, Lyon and Meyzieu (Rhône), France. They were carried out in a polyclinic, a medicalized nursing home, and in outpatient settings. Samples were analyzed by EUROFINS CBM69 Médipole laboratory.

Sampling was performed by the biologist within the laboratory, by previously trained nurses within the polyclinic, and by a member of the health care team within the medicalized nursing home.

As per recommendations, tests were reserved to patients with COVID-19 evocative symptoms such as respiratory or general symptoms (fever, asthenia, stiffness), and with one of the following criteria [2]: severe symptoms (hospitalization), severe risk factors, health care workers, pregnancy, exploration of an infection source in a community setting.

For outpatients, prescribers had to fill in a medical questionnaire to document these indications. Given the difficulty to perform this on the Lafayette site (Lyon), biologists had to collect samples exclusively at home and thus had to strictly control the prescription relevance. They prioritize situations for which a positive test would induce a change in the patient care, relying on the presence of fever and respiratory disorders, contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case, and health care workers.

Tests performed between March 12 and April 7, 2020 were included. Some of them were excluded because they were duplicate or because the file was incomplete. A total of 279 tests were analyzed.

We performed correlation tests according to the prescriber (emergency departments versus outpatient wards), to the sampler (nurses, biologists, health care team in a medicalized nursing home), and to the laboratory.

3. Results

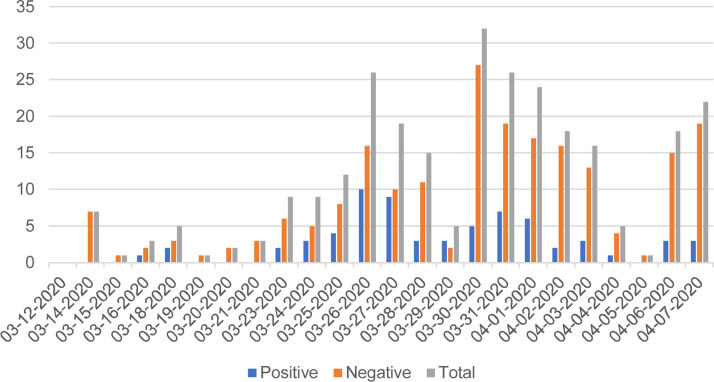

A total of 67 tests (24%) out of 279 were positive. The number of daily tests increased until March 30, reaching a peak of 32 tests performed, five of which were positive (Fig. 1 ). Overall, 20% of the tests were positive for women against 31% for men. The percentage of positive tests seemed to increase with age (30% for people aged over 81) (Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Number of tests performed by date.

Table 1.

Correlation test data and result presentation.

| Positive |

Negative |

Inconclusive |

Correlation test result |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | P | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female (n = 186) | 38 | (20) | 147 | (79) | 1 | (1) | |

| Male (n = 93) | 29 | (31) | 61 | (66) | 3 | (3) | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 0–40 (n = 85) | 16 | (19) | 68 | (80) | 1 | (1) | |

| 41–60 (n = 89) | 22 | (25) | 66 | (73) | 2 | (2) | |

| 61–80 (n = 68) | 18 | (27) | 49 | (72) | 1 | (1) | |

| 81–100 (n = 37) | 11 | (30) | 26 | (70) | 0 | (0) | |

| Prescriber | 0.04a | ||||||

| Outpatient wards (n = 191) | 42 | (22) | 146 | (76) | 3 | (2) | |

| Emergency departments (n = 58) | 21 | (36) | 36 | (62) | 1 | (2) | |

| Clinic hospitalization (n = 19) | 1 | (5) | 18 | (95) | 0 | (0) | |

| Medicalized nursing home (n = 11) | 3 | (27) | 8 | (73) | 0 | (0) | |

| Sampler | 0.67b | ||||||

| Nurse in a clinic (n = 76) | 22 | (29) | 53 | (70) | 1 | (1) | |

| Biologist (n = 192) | 42 | (22) | 147 | (77) | 3 | (1) | |

| Medicalized nursing home (11) | 3 | (27) | 8 | (73) | 0 | (0) | |

| Sampling site | |||||||

| Lafayette (Lyon) (n = 11) | 6 | (55) | 5 | (45) | 0 | (0) | |

| Croix-Rousse (Lyon) (n = 96) | 20 | (21) | 74 | (77) | 2 | (2) | |

| Loup Pendu (Rillieux-la-Pape) (n = 140) | 36 | (26) | 102 | (73) | 2 | (1) | |

| Les Verchères (Rillieux-la-Pape) (n = 11) | 3 | (27) | 8 | (73) | 0 | (0) | |

| Carreau (Meyzieu) (n = 21) | 2 | (10) | 19 | (90) | 0 | (0) | |

| Total | 67 | (24) | 208 | (75) | 4 | (1) | |

| Sampling site (samples collected by biologists) | 0.07c | ||||||

| Lafayette (Lyon) (n = 11) | 6 | (55) | 5 | (45) | 0 | (0) | 0.02d |

| Croix-Rousse (Lyon) (n = 96) | 20 | (21) | 74 | (77) | 2 | (2) | |

| Loup Pendu (n = 62) | 14 | (23) | 47 | (76) | 1 | (1) | |

| Verchères (n = 6) | 0 | (0) | 6 | (100) | 0 | (0) | |

| Carreau (n = 17) | 2 | (12) | 15 | (88) | 0 | (0) | |

Chi2 test (Yates’ correction) on prescribers: outpatient versus emergency departments.

Fischer's exact test on samplers.

Fischer's exact test on sampling sites (samples collected by biologists).

Fischer's exact test on sampling sites (samples collected by biologists): Lafayette versus other laboratories.

Outpatient prescriptions represented 191 tests, of which 42 (22%) were positive. Among those tests, 11 were performed by the Lafayette site, six of which were positive (55%). Emergency prescriptions accounted for 58 tests, of which 21 (36%) were positive.

The tests were significantly more frequently positive when prescribed within emergency departments than outpatient wards (P = 0.04). However, the type of sampler did not seem to have any impact on the test result (P = 0.67). Results of the various laboratories were of little significance (P = 0.07). However, it is interesting to compare the Lafayette site with other sites with less restrictive indications for tests. The tests were significantly more frequently positive when biologists applied a strict control of indications (P = 0.02).

4. Discussion

A peak seemed to have been reached around March 30. Chronological data seems to be similar to those of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region [3]. Indeed, the epidemic follow-up indicators have been decreasing since the first weeks of April. The positivity rate (24 %) is close but higher than the region private laboratories positivity rate (20%).

COVID-19 can have several clinical forms: from pauci-symptomatic forms to feverish respiratory distress. Patients presenting with severe symptoms are more likely to have COVID-19 and thus to be tested positive. Time between symptom onset and performance of the test can also change the results [4]; the timeframe for test positivity therefore seems to be longer in patients presenting with severe forms [5].

We can assume that patients consulting at the emergency department have more severe clinical presentations. This could explain why the tests are significantly more frequently positive in the emergency departments than in outpatient wards. Unfortunately, we were not able to collect and analyze a sufficient amount of clinical data to support these assumptions. A further study including clinical data could clarify those results.

In the present study, the rate of positive tests tends to increase with age. As previously mentioned, the clinical form could explain this result as older people are more likely to be seriously affected [6]. Besides, as older patients can have difficulty moving, their physician might only prescribe the tests for highly suspicious cases. Finally, as most elderly people live in nursing homes where the prescription rules are different, results may be biased.

The tests were significantly more frequently positive if biologists restricted their use with an additional interrogation, only allowing tests for high probability situations. Physicians are indeed subject to a certain pressure from very anxious patients. To deal with it, they can adopt a systematic attitude and test every patient presenting with the slightest clinical sign, which can be confused with signs of benign viral diseases or allergies for example. They may also have a more tempered attitude: testing highly suspicious patients. Biologists’ contribution can temper those two attitudes.

5. Conclusion

Control of the prescription relevance by biologists enabled to restrain access to the tests in order to improve the epidemic follow-up by maximizing positive results. Extension of testing indications to contain the epidemic requires biologists to adapt their practices. A further study accurately describing clinical features would allow for a more appropriate prescription of tests.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human partic-pants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

References

- 1.Kokkinakis I., Selby K., Favrat B., Genton B., Cornuz J. Covid-19 diagnosis: clinical recommendations and performance of nasopharyngeal swab-PCR. Rev Med Suisse. 2020;16(689):699–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé . Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé; 2020. COVID-19. Recommandations aux professionnels de santé en charge des prélèvements de dépistage par RT-PCR. Fiche ARS. [Internet]https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/covid-19__rt-pcr-ambulatoire-fiche-ars.pdf [quoted on 22th may 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santé publique France . Santé publique France; 2020. COVID-19 : point épidémiologique en Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes du 9 avril 2020. [Internet]https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/regions/auvergne-rhone-alpes/documents/bulletin-regional/2020/covid-19-point-epidemiologique-en-auvergne-rhone-alpes-du-9-avril-2020 [quoted on 22th may 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lippi G., Simundic A.-M., Plebani M. Potential preanalytical and analytical vulnerabilities in the laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:1070–1076. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y., Yang M., Shen C., Wang F., Yuan J., Li J., et al. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections. medRxiv. 2020 [2020.02.11.20021493] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]