Abstract

Background

Solanum melongena (SM) is commonly known as the garden egg fruit or eggplant. It can be eaten fresh or cooked and has a large history of consumption in West Africa. This study focused on interventions of aqueous extract of SM (garden eggs) fruits on Mercury chloride (HgCl2) induced testicular toxicity in adult male Wistar rats.

Methods

Thirty-two adult male Wistar rats were randomly divided into four groups (A-D) of eight (n = 8) rats each. Group A Served as control and was given 10 ml/kg/day of distilled water, Group B- 500 mg/kg B.W of SM, Group C received 40 mg/kg B.W HgCl2 and Group D- 500 mg/kg B.W of SM and 40 mg/kg B.W HgCl2). The administration was done by gastric gavage once a day, for twenty-eight consecutive days. Testicular weight, semen analysis revealing the sperm count and sperm motility were assessed, gross parameters of the testis and testicular histology were assessed. Testicular oxidative stress markers viz a viz malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and reduced glutathione (GSH) were also assessed.

Results

assessment of the histological profiles of the testes showed a derangement of the cytoarchitecture and deterioration of sperm quality after HgCl2 administration and a marked improvement was observed after SM administration. Similarly, SM was associated with increased antioxidant parameters (SOD, CAT, GPx, and GSH) and decreased MDA in SM + HgCl2 rats.

Conclusion

It was concluded that S. melongena offers protection against free radical mediated oxidative stress of rats with mercury chloride induced testicular toxicity.

Keywords: Testis, Garden eggs, Solanum melongena, Mercury chloride

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

It has been reported that mercury chloride an environment toxicant causing oxidative stress and induced reproductive dysfunction. However modulating role of Solanum melongena has not been study. Therefore, ameliorative potential of Solanum melongena on mercury chloride induced testicular toxicity was investigated using animal model.

What this study adds to the field

Solanum melongena augments spermatogenesis and attenuates HgCl2 induced testicular toxicity through an antioxidant system of activities. Therefore, we can infer from our findings that Solanum melongena has pro-fertility properties. Thus, it is recommended for infertile men.

Mercury has been recognized as an industrial hazard that adversely affects the male reproductive system of humans and animals [1]. Mercury (Hg) is a ubiquitous element in the environment causing oxidative stress in the exposed individuals thereby leading to tissue damage. Its contamination and toxicity have posed a serious hazard to human health. Mercury is a highly toxic metal that results in a variety of adverse neurological, renal, respiratory, immune, dermatological, reproductive and developmental disorders [2]. Its wide industry-related effects on humans and animal biosystem have been well documented [3]. The release of mercury from dental amalgam dominates exposure to inorganic mercury and may have an acceptable risk among the general population [4]. Mercury affects accessory sex glands function in rats and mice through androgen deficiency [5]. Mercury chloride (HgCl2) is one of the most toxic forms of mercury because it easily forms organomercury complexes with proteins [6]. HgCl2 has been reported as highly toxic metal that results in a variety of adverse hepatotoxic, hematological changes and also nephrotoxic effects on male Wistar rats [7], [8]. Consumption of a high quantity of mercury-contaminated fish changes the blood pressure and cardiac autonomic activity [9]. HgCl2 is considered to be one of the pro-oxidants that induce oxidative stress [10]. Oxidative stress occurs when the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as, superoxide anion (•O−2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical (•OH) exceeds the body's defense mechanism, causing damage to macromolecules such as DNA, proteins, and lipids [11] and trigger many pathological processes in the male reproductive system [12]. Excessive production of ROS above normal levels results in lipid peroxidation and membrane damage leading to loss of sperm motility [13].

Solanum melongena (SM) commonly called African eggplant or garden egg is among the oldest vegetables indigenous to tropical Africa [14]. It is widely cultivated across West Africa especially for the nutritional, medicinal and economic values of its leaves and fruits. The fruit may be consumed freshly raw, dried, cooked and in salad form [15]. SM is a common and popular vegetable crop grown in the subtropics, tropics and it is called “brinjal” in India, “yalo” in the Hausa tradition of northern Nigeria and “aubergine” in Europe [16]. Eggplant is a perennial plant but grown commercially as an annual crop [17]. The fruit is easily eaten as a snack and it has been reported to be high in phytochemicals like saponins, flavonoids, tannins, dietary fiber, alkaloids, nasunin, steroids, proteins, carbohydrates and ascorbic acid in both the crown and the fruit [18], [19], [20], [21].

The testis is the main organ of the male reproductive system and the testicular parenchyma is composed of seminiferous tubules from which spermatozoa are produced that maintain generation and Leydig cells that produce testosterone which is responsible for male sexuality and secondary male sex characteristics [22], [23], [24]. There are several numbers of agents that can adversely affect the male reproductive system. These occur by interfering with sexual maturation, production, and transport of spermatozoa, the spermatogenic cycle, sexual behavior and fertility [25]. These agents may also play an adverse or beneficial role on the Leydig cells, thereby affecting testosterone production [26]. An in vivo study using adult male mice found a reduction in sperm count in the testis, vas deferens, and cauda epididymis revealing the inhibitory effects of HgCl2 on spermatogenesis [27]. Rats exposed to HgCl2 for 81 days experienced a reduction in the weights of the left and right testes and prostate in a high-dose group, and the seminal vesicles weights, in mid and high-dose groups, were significantly decreased when compared to controls [28]. Male fertility can be impaired by various toxicants known to target Sertoli cells, which play an essential role in spermatogenesis. Sertoli cells from male Sprague–Dawley rats exposed in vitro to mercury had severely inhibited inhibin production [29]. Bull spermatozoa exposed to 50–300 μmol/L concentration range of HgCl2 revealed reduced sperm membrane and DNA integrity [30]. This study, therefore, focused on the assessment of interventions of aqueous extract of SM on HgCl2 induced testicular toxicity in adult male Wistar rats.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade. They were products of Sigma Aldrich, Germany.

Plant material

Fresh fruits of SM were bought from “Oja Oba” market in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria in the month of April. Botanical identification was performed at the Herbarium section of Biological Science Department of Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria by Dr.K.D Ileke.

Extraction of plant material

The extraction of the plant material was done by modification of the method reported by Jamil et al. [31]. The fruits were thoroughly washed in sterile water and were shade-dried to a constant weight in the laboratory. The air-dried fruits were weighed using Gallenkamp (FH2406B, England) electronic weighing balance and were milled with automatic electrical Blender (model FS-323, China) to a powdered form. An aqueous extract was made from 1 kg of SM fruits which were soaked in distilled water (5 L) and the mixture boiled for 15 min. The heated decoction was taken and allowed to cool at room temperature, filtered and oven-dried as described by Pierre et al. [32] to give a dried aqueous extract that weighs 60.2 g. The extraction was carried out in the Department of Food Laboratory, Federal University of Technology, Akure. The working solution was prepared at a final concentration of 154 mg/ml in distilled water.

Administration of extract and mercury chloride

Aqueous extract of SM was administered orally by gastric gavage at a dose of 500 mg/kg body weight daily for 28 days, while 40 mg/kg body weight of HgCl2 was administered orally daily for 28days. The oral LD50 for HgCl2 was calculated to be 75 mg/kg [33].

Experimental animals

A total of 32 adult male Wistar rats weighing between (170 ± 30 g) were used for the study. The rats were fed with standard rat chow. They had access to water ad libitum. The rats were randomly divided into 4 groups of 8 rats per group. A-control group received normal saline, Group B- 500 mg/kg B.W of SM fruit extract, Group C- 40 mg/kg B.W of HgCl2 and Group D-500 mg/kg B.W of SM fruit extract + 40 mg/kg B.W HgCl2. All experimental protocols followed the guidelines stated in the “Guide to the care and use of Laboratory Animals Resources”, National Research Council, DHHS, Pub. No NIH 86–23 [34] and in accordance with ethical approval of the Department of Human Anatomy, Federal University Technology, Akure, Nigeria.

Collection of samples

At the end of the experimental period, blood was obtained for biochemical analysis by puncturing the retro-orbital venous sinus. After collection of blood samples, the animals from all groups were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the testes, vas deferens, epididymis, prostate glands, and seminal vesicles were excised from surrounding tissues and placed into tubes. Organs were dried between two sheets of filter paper and their wet weight was determined. The gonadosomatic index (GSI) was expressed as a percentage of the total body weight in relation to the testis weight, GSI = (testes weight/total body weight) × 100. Left epididymis was weighed, while right epididymis was rinsed in warm phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for the evaluation of sperm quality. Whereas left testes were processed for histological procedure, right testes were processed for determination of MDA, GSH, SOD, CAT, and GPx.

Semen analysis

Orchidectomy was performed by open castration method. The testicle was exposed by incising the tunica vaginalis and the cauda epididymides were harvested. The cauda epididymides of rats in each of the experimental group were removed and minced thoroughly in a specimen bottle containing normal saline for few minutes to allow the sperms to become motile and swim out from the cauda epididymis [35].

Sperm count and motility studies

The semen was then taken with a 1 ml pipette and dropped on a clean slide, and covered with coverslips. The slides were examined under a light microscope for sperm motility [36]. And with the aid of the improved Neubauer hemocytometer (Deep 1/10 mm LABART, Germany) counting chamber as described by Asada et al. [37], the spermatozoa were counted under the light microscope. Counting was done in five chambers.

Determination of oxidative stress parameters

Testicular superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined according to the method described by Aebi [38] and GSH-Px activity was determined by GSH-Px assay kit, detailed procedures for the above measurements were performed according to the kits' protocol. Catalase activity (CAT) was estimated in testis homogenate by the method reported by Moron et al. [39]. The specific activity of catalase has been expressed as μmoles of H2O2 consumed/min/mg protein. The difference in absorbance at 240 nm per unit time is a measure of catalase activity. The non-enzymic GSH was analyzed by the method of Ohkawa et al. [40].

Determination of testicular malondialdehyde (MDA)

The lipid peroxidation products were evaluated by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) [41] and were determined by modifying the method of Goering et al. [42].

Testicular histology preparation

The histology of the testes was done by modification of the method reported by Oluyemi et al. [43]. The organs were harvested and fixed in Bouin's fluid for 24 h after which it was transferred to 70% alcohol for dehydration. The tissues were passed through 90% and absolute alcohol and xylene for different durations before they were transferred into two changes of molten paraffin wax for 1 h each in an oven at 65 °C for infiltration. They were subsequently embedded and serial sections cut using rotary microtome at 5 microns. The tissues were picked up with albumenized slides and allowed to dry on a hot plate for 2 min. The slides were dewaxed with xylene and passed through absolute alcohol (2 changes); 70% alcohol, 50%alcohol and then to water for 5 min. The slides were then stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of X100.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences between the groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed the Newman–Keuls (SNK) test for multiple comparisons. Differences yielding p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses of data were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Results

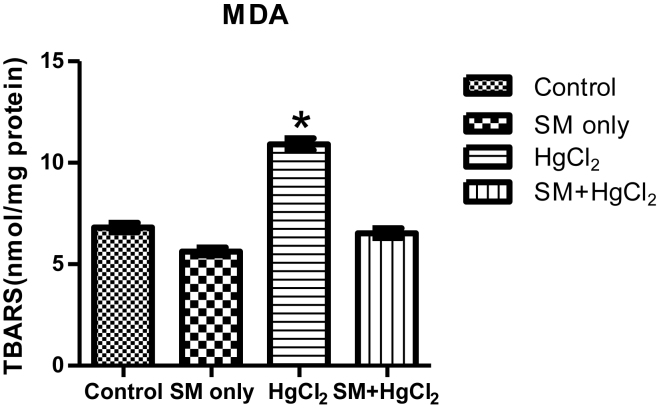

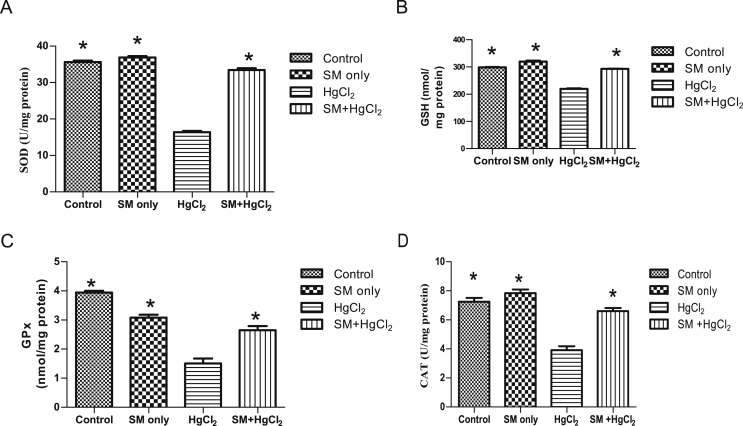

MDA levels and antioxidant (CAT, SOD, GSH, GPx) levels

As shown in Fig. 1, the MDA levels in the HgCl2 group increased significantly (p < 0.05) compared with the control and SM group but decreased in SM + HgCl2 group compared to the HgCl2 only group. The anti-oxidant levels (CAT, SOD, GSH, and GPx) decreased significantly in the HgCl2 group compared to the control group. The CAT, SOD, GSH, and GPx levels in SM and SM + HgCl2 group was also increased (p < 0.05) compared to the HgCl2 only group [Fig. 2].

Fig. 1.

Effects of HgCl2 and SM treatment on TBARS (nmol MDA/mg protein) levels of testicular damage. Bars are mean ± SEM. * Significantly higher than Control, SM, SM + HgCl2 at p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Effects of HgCl2 and SM treatment on testicular antioxidant levels of experimental rats: (A) SOD, (B) GSH, (C) GPx and (D) CAT). Bars are mean ± SEM. * Significantly dissimilar from HgCl2 at p < 0.05.

Sperm motility and sperm count analysis

After twenty-eight days (28 days) of the administration, there was a significant decreased in mean sperm motility of group C treated with 40 mg/kg BW of Mercury chloride in comparison with groups A, B, and D treated with normal saline, 500 mg/kg BW of SM fruit extract, and 500 mg/kg of SM fruit extract and 40 mg/kg BW mercury chloride (p < 0.05). There was also decreased in sperm motility of groups B and D compared to control group A. The groups of rats that were treated with 40 mg/kg BW of Mercury chloride (Group C) demonstrated significant decrease in sperm count when compared to groups A, B, and D values, also sperm count of groups B and D significantly lower than that of the control group (p < 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Effects of HgCl2 and SM treatment on Sperm motility and sperm count after 28 days.

| Groups | Description | Motility (%) | Sperm Count (x 106/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Control (Normal saline) | 89.48 ± 3.07+ | 88.93 ± 1.68+ |

| B | 500 mg/kg of Solanum melongena | 83.91 ± 2.75+* | 81.11 ± 2.26 +* |

| C | 40 mg/kg of HgCl2 | 39.39 ± 0.78* | 27.80 ± 0.62* |

| D | 40 mg/kg HgCl2 and 500 mg/kg Solanum melongena | 72.88 ± 3.36+* | 79.41 ± 1.09 +* |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 8; +Significantly higher from the HgCl2 group (p<0.05); * Significantly dissimilar from the Control group (p<0.05).

Weights of the body and reproductive organ

The values of body and organs weights are shown in [Table 1]. There was a significant increase in the body weight of the experimental animals across the groups. The weights of testes and accessory sex organs were significantly lower (p < 0.05) in HgCl2-treated group when compared with the control and SM group. However, the values of accessory sex organs of SM + HgCl2 group were significantly higher than those of the HgCl2 group. Also, the gonadosomatic index (GSI) value of the HgCl2 group was significantly lower than that of control (p < 0.05) and SM treated groups. The GSI of SM + HgCl2 was lower (not significantly) compared to the control group.

Table 1.

Body, organ weights (g) and the gonadosomatic index (GSI) of adult rats treated with Solanum melongena and HgCl2 for twenty-eight days.

| Groups | Initial weight(g) | Final weight | Testis | GSI | Epididymis | Vas deference | Ventral prostate | Seminal vesicle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 177.0 ± 1.35 | 221.80 ± 1.8+ | 1.78 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.02+ | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 |

| Group B | 174.9 ± 1.04 | 208.00 ± 1.6+ | 1.67 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.02+ | 0.16 ± 0.01* | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.02* | 0.85 ± 0.01 |

| Group C | 173.5 ± 1.27 | 187.40 ± 1.1 | 1.35 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.0 | 0.15 ± 0.01* | 0.09 ± 0.01* | 0.38 ± 0.02* | 0.47 ± 0.01* |

| Group D | 177.6 ± 1.15 | 195.40 ± 1.43+ | 1.44 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.04* | 0.11 ± 0.01* | 0.46 ± 0.02* | 0.58 ± 0.01* |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 8; *Significantly different from Group A at p < 0.05; +Significantly dissimilar from Group C at p < 0.05.

Group A: Control (Normal saline); Group B: 500 mg/kg B.W of SM; Group C: 40 mg/kg B.W of HgCl2; Group D: 40 mg/kg B.W of HgCl2 +500 mg/kg SM.

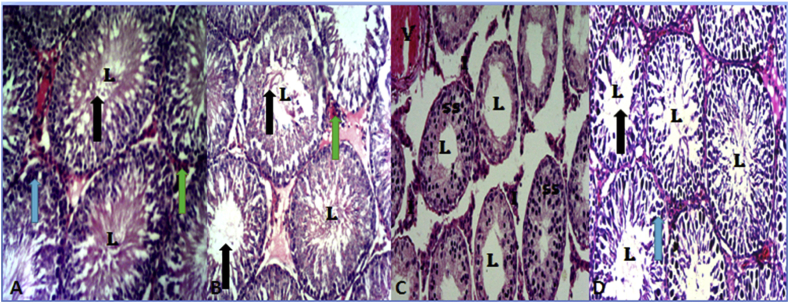

Histology of the testes

Cross section of the testis of animals after 28 days of the study shown that group A had normal testis histoarchitecture with normal seminiferous tubule composed of supporting cells (Sertoli cells) and spermatogenic cells. The spermatozoa are arranged in rows between and around the cells of Sertoli. Group B showed matured spermatozoa in the lumen of seminiferous tubules. In group C there is degeneration of the spermatogenic cells of the germinal epithelium, occlusion of the lumen of seminiferous tubules, hypertrophy of seminiferous tubules and irregular vacuolized basement membrane. Group D showed normal cellularity in germinal epithelium, increased in the spermatogenic cells in the lumen of seminiferous tubules and interstitial cells of Leydig in the interstitium compared with the control [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of the testis of rats in control (A), SM (B) and SM + HgCl2 (C) groups illustrating the typical structure of the seminiferous tubule showing the stages of spermatogenesis, spermatogonia (light blue arrows), sperm cells (black arrows), and the interstitial cells of Leydig (green arrow), sperm cells in the lumen (L) and normal germinal epithelium (GM). Group C (HgCl2) showing hypocellularity, reduction in cells of the spermatogenic series (SS) as a result of degeneration, sloughing and shortening of seminiferous epithelium; The seminiferous tubules show a single layer of basal spermatogonia; widened empty lumen (L); widened interstitium (I) due to tubular atrophy as a result of degeneration, and V shows vascular haemorrhage.

Discussion

Mercury is a widespread toxic environmental and industrial pollutant [44]. It has been reported that exposure of experimental animals to inorganic or organic forms of mercury are associated with induction of oxidative stress [45], [46]. Oxidative damage may result from decreased clearance of ROS by scavenging mechanisms. Generation of ROS in the cytoplasm of cells may increase the hydrogen peroxide production and lipid peroxidation of the mitochondrial membrane, resulting in loss of membrane integrity and finally cell necrosis or apoptosis [47], [48], [49].

In this study, consumption of HgCl2 is associated with increased levels of oxidative stress and decreased levels of GSH along other antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, and GPx) [Fig. 2]. The decrease in SOD, CAT, GSH and GPx levels in the testis suggests the toxic effects of HgCl2 in the experimental rats. The administration of SM countered the action of HgCl2 on testicular cells thereby mitigating the decrease in antioxidants levels. Since the significance of GSH in the detoxification of chemically reactive metabolite in drug-induced toxicity after a decrease in GSH has been well established [50], [51], it then follows that an increase in oxidation and decreased synthesis of GSH would cause a decrease in GSH levels. Therefore, an increase in antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, GSH, and GPx) after administration of SM might contribute to ameliorating oxidative stress.

MDA is a known biomarker of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. The increased MDA levels in testicular tissue associated with the administration of HgCl2 in this study is an important indication of lipid peroxidation as reported by De Lamirande and Gagnon [52]. Treatment of rats with a combination of SM and HgCl2 attenuated the HgCl2 induced increase in MDA content, which indicates that SM is rich in antioxidant constituents such as phenol, chlorogenic acid, anthocyanin, ascorbic acid and flavonoids [19], [20], [21]. We can deduce that these rich antioxidant constituents of SM boosted the testicular enzymatic antioxidants to effectively scavenge the free radicals preventing lipid peroxidation, therefore reducing HgCl2 toxicity.

In the present investigation, reduction in sperm count, epididymis weight and motility were accompanied with an increased in abnormalities of sperm in rats following exposure to HgCl2, which imply that HgCl2 may interfere with spermatogenesis by crossing the blood-testis barrier and gaining access to germinal cells. The adverse effects of HgCl2 on mammalian testicular tissue have been reported with marked testicular spermatogenic degeneration at the spermatocyte level in rats [13]. The spermatozoa membranes are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, so they are susceptible to ROS attack and lipid peroxidation [53] as a result of exposure to mercury. Lipid peroxidation reaction causes membrane damage which leads to a decrease in sperm motility, presumably by a rapid loss of intracellular ATP, and an increase in sperm morphology defects [54], [55]. Mercury compounds have been reported to cause DNA breaks by means of free-radical-mediated reactions [45] that may cause an increase in the frequency of spermatozoa with abnormal heads.

Several active components in SM [19], [20], [21] may scavenge ROS generated by mercury, reduce lipid peroxidation and enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes whereby leading to protection against mercury-induced testicular toxicity which is manifested by an increase in sperm abnormalities. This result indicates that SM fruits extract has an effect on the mitochondria found in the body of the spermatozoon where energy is being synthesized in form of adenosine triphosphate, that increases the sperm motility [56]. Hence, the antioxidative properties of SM may play a positive role in the defense against oxidative stress induced by HgCl2.

A Previous study has reported weight reductions of accessory sex organs after HgCl2 and Spirulina platensis administration [57]. In this study, the values of body and organs weights are shown in Table 1. There was a significant increase in the body weight of the experimental animals across the groups and the weights of testes and accessory sex organs decreased significantly (p < 0.05) in HgCl2 treated and SM + HgCl2 groups when compared with the control and SM groups. However, the values of accessory sex organs of SM + HgCl2 group were significantly higher than those of the HgCl2-exposed group. Also, the gonadosomatic index (GSI) value of HgCl2-treated and SM + HgCl2 group was significantly lower than that of control and SM treated groups. This is in disagreement with the report that the aqueous extract of SM fruits has the potential to decrease mean body weights of rats [31]. This also disagrees with the report that garden eggplant reduces weight gain by reducing the serum total cholesterol, triglyceride and increase serum HDL cholesterol in the comparative study of the effect of SM (garden egg) fruit, oat, and apple on serum lipid profile [58].

In this study, HgCl2 treatment is associated with degeneration of the spermatogenic cells of the germinal epithelium, occlusion of the lumen of seminiferous tubules, hypertrophy of seminiferous tubules and irregular vacuolation of the basement membrane. For decades, it has been made clear that testosterone which is produced by the interstitial cells of Leydig is a necessary prerequisite for the maintenance of established spermatogenesis [59]. The reduced cellularity of the interstitium in testis of animals treated with HgCl2 only would lead to a decrease in testosterone resulting in the poor spermatogenesis observed. The group B treated with SM only compared very well with the control group; it revealed normal histoarchitecture of the testes and abundant luminal spermatozoa after twenty-eight days of oral consumption of SM fruit [Fig. 3]. This is in accordance with the report of Jamil et al. [31], that aqueous extract of SM fruit did not induce any lesion in the histology of the testes after twenty-eight days of administration. These also concur with the work of Cody et al., Harbone and Williams, who stated that plants containing flavonoids are effective in the prevention of lesion, mainly because of their antioxidant properties [60], [61], [62]. However, in all the test groups, there was an observed increased in spermatogenic activity towards the lumen of the seminiferous tubule. This increase cellular activity was from the basement membrane up to the lumen of the seminiferous tubules of the testes. This was evidenced by the reduced number of primary spermatogonia cells. This is an indication that they might have differentiated to next level of spermatogenic cells. From our observation, when SM aqueous extract was administered concurrently with HgCl2, it protected the testis from the harmful effects of HgCl2. This protective nature of SM aqueous extract is enhanced by some of its antioxidant constituents [19], [20], [21] the presence of ascorbic acid and flavonoids which is known for their protection on cell membranes and scavenging effects on free radicals and increased testosterone formation by the interstitial cells of Leydig [61], [63], [64].

We, therefore, conclude that HgCl2 caused a lesion in the germinal epithelium and hypocellularity of the interstitium. However, SM promoted germinal epithelial growth and protected the cytoarchitecture of the testis from lesions due to the harmful effect of HgCl2. SM augments spermatogenesis and attenuates HgCl2 induced testicular toxicity through an antioxidant system of activities. Therefore, we can infer from our findings that SM has pro-fertility properties which may be beneficial to those who eat it.

Ethical approval

All authors hereby declare that all experiments have been examined and approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Acknowledgment

Authors are grateful to Dr. Ileke for the identification and authentication of the plants used for this research work.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Mohamed A.B., Khaled H., Fadhel G., Ali B., Asma O., Abdelaziz K. Testicular toxicity in mercuric chloride treated rats: association with oxidative stress. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risher J.F., Amler S.N. Mercury exposure: evaluation and intervention, the inappropriate use of chelating agents in the diagnosis and treatment of putative mercury poisoning. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . WHO; Geneva: 1991. World health organization. Inorganic mercury, environmental health criteria No 118. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekstrand J., Bjorkman L., Edlund C., Sandborgh E. Toxicological aspects on the release and systemic uptake of mercury from dental amalgam. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998;106:678–686. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1998.eos10602ii03.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao M. Histophysiological changes of sex organs in methyl mercury intoxicated mice. Endocrinol Exp. 1989;23:60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorschieder F.L., Vimy M.J., Summers A.O. Mercury exposure from “silver” tooth filling: emerging evidence questions a traditional dental paradigm. FASEB J. 1995;9:504–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzunhisarcikli M., Aslantürk A., Kalender S., Apaydın F.G., Baş H. Mercuric chloride-induced hepatotoxic and hematologic changes in rats: the protective effects of sodium selenite and vitamin E. Toxicol Ind Health. 2016;32:1651–1662. doi: 10.1177/0748233715572561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apaydın F.G., Bas H., Kalender S., Kalender Y. Subacute effects of low dose lead nitrate and mercury chloride exposure on the kidney of rats. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;41:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valera B., Dewailly E., Poirier P. Impact of mercury exposure on blood pressure and cardiac autonomic activity among Cree adults. Environ Res. 2011;111:1265–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan A., Atkinson A., Graham T., Thompson S., Ali S. Effects of inorganic mercury on reproductive performance of mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valko M., Morris H., Cronin M.T. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr Med Chem. 1995;12:161–208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal A., Saleh R.A., Bedaiwy M.A. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:829–843. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04948-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vachhrajani K., Makhija S., Chinoy N., Chowdhury A. Structural and functional alterations in testis of rats after mercuric chloride treatment. J Reprod Biol Comp Endocrinol. 1988;8:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prohens J., Blanca J.M., Neuz F. Morphological and molecular variation in a collection of eggplant from a secondary centre of diversity: implications for conservation and breeding. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2005;130:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anosike C.A., Obidoa O., Ezeanyika L.U. The anti-inflammatory activity of garden egg (Solanum aethiopicum) on egg albumin-induced oedema and granuloma tissue formation in rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:62–66. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veeraragavathatham T., Jawaharlal M., Seemanthini R. Tamil Nada Agricultural University; Coimbatore: 2006. SUSVEG- asia bringal manual (TNAU) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westerfield Robert. 2008. Pollination of vegetable crops.http://pubs.caes.uga.edu/caespubs/pubs/PDF/C93 4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinedu S.N., Olasumbo A.C., Eboji O.K., Emiloju O.C., Arinola O.K., Dania D.I. Proximate and phytochemical analyses of Solanum aethiopicum L. And Solanum macrocarpon L. Fruits. Res J Chem Sci. 2011;1:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson P.M., Yanga R.Y., Tsoua S.C., Ledesmaa D., Englea L., Lee T.C. Diversity in egg plant (Solanum melongena) for superoxide scavenging activity, total phenolics, and ascorbic acid. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;219:594–596. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noda Y., Kneyuki T., Igarashi K., Packer M.L. Antioxidant activity of nasunin, an anthocyanin in eggplant Peels. Toxicology. 2000;148:119–123. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiwari A., Jadon R.S., Tiwari P., Nayak S. Phytochemical investigations of crown of Solanum melongena fruit. Int J Phytomed. 2006;1:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Copenhaver W.M., Kelly D.E., Wood R.L. 17th ed. The Williams and Wilkins Company; Philadelphia, USA: 1978. Bailey's text book of histology; pp. 611–643. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellmann H.D., Eurell J.A. 5th ed. Williams and Wilkins, A Waverly Company; Philadelphia, USA: 1998. A textbook of veterinary histology; pp. 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hafez R.S. 7th ed. vols. 3–12. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia, USA: 2000. pp. 37–43. (Reproduction in farm animals). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimmel G.L., Clegg E.D., Crisp T.M. Reproductive toxicity testing: a risk assessment perspective. In: Witorsch R.J., editor. Rep.Toxicol. 2nd ed. Raven Press; New York: 1995. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooradian A.D., Morley J.E., Korenman S.G. Biological actions of androgens. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:1–28. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma A.K., Kapadia A., Fransis G.P., Rao M.V. Reversible effects of mercuric chloride on reproductive organs of the male mouse. Reprod Toxicol. 1996;10:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(95)02058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atkinson A., Thompson S.J., Khan A.T., Grahamu T.C., Ali S., Shannon C. Assessment of a two-generation reproductive and fertility study of mercuric chloride in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monsees T.K., Franz M., Gebhardt S., Winterstein U., Schill W.B., Hayatpour J. Sertoli cells as a target for reproductive hazards. Andrologia. 2000;32:239–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2000.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arabi M. Bull spermatozoa under mercury stress. Reprod Domest Anim. 2005;40:454–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2005.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamil D.U., Mabrouk M.A., Alhassan A.W., Magaji R.A. Effect of aqueous extract of Solanum melongena fruits (garden eggs) on some male reproductive variables in adult wistar rats. Rep Opinion. 2015;7:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierre W., Esther N., Nkeng-Efouet P., Alango N.T., Benoît A.K. Reproductive effects of Ficus asperifolia (Moraceae) in female rats. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:49–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghaleb A.O., Tahia H.S., Rajashri R.N., Said Z.M., Reda M.A. A sub-chronic toxicity study of mercuric chloride in the rat. Jordan J Biol Sci. 2012;5:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Research Council . 1985. DHHS, pub. No NIH 86 – 23. Guide to the care and use of laboratory animals Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saalu L.C., Udeh R., Oluyemi K.A., Jewo P.I., Fadeyibi L.O. The ameliorating effects of grape fruit seed extract on testicular morphology and function of varicocelized rats. Int J Morphol. 2008;26:1059–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pant, Srivastava Testicular and spermatotoxic effects of quinalphos in rats. J Appl Toxicol. 2003;23:271–274. doi: 10.1002/jat.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asada K., Takahashi M., Nagate M. Assay and inhibitors of spinach superoxide dismutase. Agric Biol Chem. 1984;38:471–473. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moron M.S., Depierre J.W., Mannervik B. Levels of GSH, GR and GST activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;582:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. Assay of lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1984;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aboul-Soud M.A., Al-Othman A.M., El-Desoky G.E., Al-Othman Z.A., Yusuf K., Ahmad J. Hepatoprotective effects of vitamin E/selenium against malathion-induced injuries on the antioxidant status and apoptosis-related gene expression in rats. J Toxicol Sci. 2011;36:285–296. doi: 10.2131/jts.36.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goering P.L., Morgan D.L., Ali S.F. Effect of mercury vapour inhalation on reactive oxygen species and antioxidant enzymes in rat brain and kidney are minimal. J Appl Toxicol. 2002;22:167–172. doi: 10.1002/jat.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oluyemi K.A., Jimoh O.R., Adesanya O.A., Omotuyi I.O., Josiah S.J., T Oyesola T.O. Effects of crude ethanolic extract of Garcinia cambogia on the reproductive system of male Wistar rats (Rattus novergicus) Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:1236–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nogueira C.W., Soares F.A., Nascimento P.C., Muller D., Rocha J.B. 2, 3- Dimercaptopropane -1-sulfonic acid and meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid increase mercury- and cadmium-induced inhibition of σ-amino levulinate dehydratase. Toxicology. 2003;184:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park E.J., Park K. Induction of reactive oxygen species and apoptosis in BEAS-2B cells by mercuric chloride. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007;21:789–790. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jezek P., Hlavata L. Mitochondria in homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in cell, tissues, and organism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:2478–2503. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaur P., Aschner M., Syversen T. Glutathione modulation influences methyl mercury-induced neurotoxicity in primary cell cultures of neurons and astrocytes. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh I.S., Datar S., Koch C.J., Shapiro I.M., Shenker B.J. Mercuric compounds inhibit human monocyte function by inducing apoptosis: evidence for formation of reactive oxygen species, development of mitochondrial membrane permeability transition and loss of reductive reserve. Toxicology. 1997;124:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(97)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saalu L.C., Oyewopo A.O., Enye L.A., Ogunlade B., Akunna G.G., Bello J. The hepatorejuvinative and hepato-toxic capabilities of Citrus paradise Macfad fruit juice in Rattus Norvegicus. Afri J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;6:1056–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trush M.A., Mimnaugh E.G., Gram T.E. Activation of pharmacologic agents to radical intermediates. Implications for the role of free radicals in drug action and toxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:3335–3346. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90609-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boujbiha M.A., Hamden K., Guermazi F., Bouslama A., Omezzine A., Kammoun A. Testicular toxicity in mercuric chloride treated rats: association with oxidative stress. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mandava V. Rao BG Antioxidative potential of melatonin against mercury-induced intoxication in spermatozoa in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:935–942. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Lamirande E., Gagnon C. Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa. I. Effects on the motility of intact spermatozoa and on sperm axonemes; and II. Depletion of adenosine triphosphate plays an important role in the inhibition of sperm motility. J Androl. 1992;13:368–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kistanova E., Marchev Y., Nedeva R., Kacheva D., Shumkov K., Georgiev B. Effect of the Spirulina platensis induced in the main diet on boar sperm quality. Biotechol Anim Husb. 2009;25:547–557. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duke J. St. Martin's Press; US: 1998. The Green Pharmacy: The ultimate compendium of Natural remedies from the world's foremost Authority on healing and herbs. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaber E.E., Samir A.B., Ibrahim M.A., Zeid A.A., Mourad A.M. Aboul-Soud et al. Improvement of Mercuric Chloride-Induced Testis Injuries and Sperm Quality Deteriorations by Spirulina platensis in rats. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edijala J.K., Asagba S.O., Eriyamremu G.E., Atomatofa U. Comparative effect of garden egg fruit, oat and apple on serum lipid profile in rats fed a high cholesterol diet. Pak J Nutr. 2005;4:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zirkin B.R. Spermatogenesis: its regulation by testosterone and FSH, Semin. Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:417–421. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cody V., Middleton E., Harborne J.B. Plant flavonoids in biology and medicine biochemical, pharmacological and structural-activity relationships. Alan Liss; New York: 1986. pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harborne J.B., Williams C.A. Advances in flavonoids research since 1992. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:481–504. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eskenazi B., Kidd S.A., Marks A.R., Sloter E., Block G., Wyrobek A.J. Antioxidant intake is associated with semen quality in healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1006–1012. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ukwenya V., Ashaolu O., Adeyemi D., Obuotor E., Tijani A., Abayomi Biliaminu A. Evaluation of antioxidant potential of methanolic leaf extract of Anacardium Occidentale (Linn) on the testes of streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. Eur J Anat. 2013;17:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saalu L.C., Oluyemi K.A., Omotuyi I.O. α-tocopherol (vitamin E) attenuates the testicular toxicity associated with experimental cryptorchidism in rats. Afri J Biotech. 2007;6:1373–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ledesmaa D., Englea L., Lee T.C. Diversity in eggplant (Solanum melongena) for superoxide scavenging activity, total phenolics, and ascorbic acid. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;219:594–596. [Google Scholar]