The cardiovascular complications of patients infected with COVID‐19, the prognostic impact of baseline cardiovascular conditions in infected patients, and the potential for angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker interaction with COVID‐19 severity has garnered considerable attention and research. Yet, the pandemic's psychosocial impact on an uninfected patient's decision to voluntarily present to the hospital for non‐COVID‐19 urgent care is yet to be completely understood or investigated. Acute heart failure (AHF) is the most common reason for hospital admission among the elderly, and the rate of AHF hospitalizations may increase during natural disasters. 1 However, behind the curtain of the COVID‐19 pandemic a concerning trend is emerging. Patients are reluctant to present to the hospital for urgent or emergent non‐COVID‐19 reasons, including AHF.

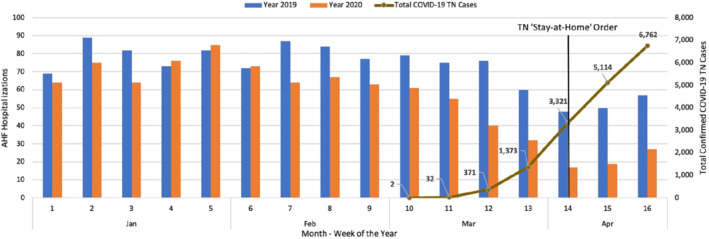

Early reports of patient‐initiated healthcare system interactions indicate patients are prioritizing avoidance of potential COVID‐19 exposure over their health needs. Internationally, patients are avoiding or delaying care for emergent conditions such as acute coronary syndrome and stroke. 2 , 3 In response, the American College of Cardiology released a statement urging patients to seek medical care for heart attack and stroke symptoms. 4 Rapid quantification of AHF admissions is more difficult than other cardiovascular conditions because it is a clinical diagnosis which is often not clear immediately upon hospital admission. Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) is experiencing an unprecedented decrease in AHF hospital admissions, which is echoed in conversations with various academic medical centres across the country. We report admissions to VUMC for AHF, illustrating a mean decrease of 62 ± 7% in the AHF hospital census from March 22nd to April 20th relative to the same calendar day last year (Figure 1 ). 5 The percentage difference in AHF hospitalizations from 2019 to 2020 was significantly different (−11 ± 12% vs. −46 ± 16%, P = 0.0012) in the pre‐COVID‐19 period (Weeks 1–9) compared to the COVID‐19 period (Weeks 10–16). Normally, reports of national AHF hospitalization rates originate from administrative coding or quality registries, but these methods can be impeded by delays in reporting and analysis. No other data are currently available to determine the extent of decrease in hospitalizations for AHF. While limited in scope, our single‐centre AHF hospitalization data are based upon a validated algorithm using clinical variables collected and recorded in real time. 6

Figure 1.

The number of hospital admissions for acute heart failure (AHF) in weekly intervals to Vanderbilt University Medical Center decreased both compared to the same time period in 2019 and in current year as confirmed cases of COVID‐19 began to rise. 5 The ‘stay‐at‐home’ order for the state of Tennessee (TN) was signed on April 2, 2020.

Delaying care until symptoms are critical could theoretically lead to fewer admissions but a higher severity of illness in patients that do seek care. However, patient characteristics of severity at AHF hospital admission were not different between the pre‐COVID‐19 period and the following COVID‐19 period of 2020 at VUMC. Patients did not differ in admission systolic blood pressure (120 ± 23 mmHg vs. 117 ± 22 mmHg, P = 0.25), blood urea nitrogen (33 ± 23 mg/dL vs. 34 ± 26 mg/dL, P = 0.64), serum creatinine (1.9 ± 1.6 mg/dL vs. 1.6 ± 1.2 mg/dL, P = 0.16), B‐type natriuretic peptide (1121 ± 1319 pg/mL vs. 1198 ± 1324 pg/mL, P = 0.58), or serum sodium (138 ± 4 mEq/L vs. 137 ± 5 mEq/L, P = 0.62) in the pre‐COVID‐19 period and COVID‐19 period, respectively. Likewise, neither the need for admission to an intensive care unit (17% vs. 22%, P = 0.25), length of stay (9 ± 8 days vs. 11 ± 10 days, P = 0.07) nor the inpatient mortality rate (5.9% vs. 2.8%, P = 0.16) differed in the pre‐COVID‐19 period and COVID‐19 period, respectively. Compared to the pre‐COVID‐19 period, older patients may have been less likely to seek AHF hospital admission during the COVID‐19 period [mean age 68 years, 95% confidence interval (CI) 67–70 vs. 66 years, 95% CI 64–68; P = 0.13] but the difference in mean patient age was not statistically significant.

Of the numerous consequences of decreasing AHF hospitalizations, the adverse impact on patient health is the most concerning. Patient's quality of life may be diminished by trying to suffer through debilitating symptoms under a cloud of anxiety that the very care one needs necessitates going to the perceived most dangerous place. Measures to decrease AHF hospital admissions for reimbursement reasons have been associated with increases in mortality, raising the question if suppression of AHF hospitalizations at the patient‐level could increase the risk of death. 7 While we did not observe a trend toward increased mortality in our cohort, a larger population is needed to adequately investigate this question. Additionally, clinical trials with AHF hospitalizations as a primary endpoint may require longer‐than‐anticipated study durations to adequately measure differences between treatments. These changes in study duration will need to be incorporated into the statistical analysis plan well in advance of the original planned endpoint of the study as the number of patients being followed is reduced over time, especially if there is a planned duration of follow‐up.

The reasons patients delay care are likely multifactorial and complex. The intense media coverage could unintentionally move patients from a healthy respect for COVID‐19 into a state of fear, in which the hospital is viewed as a danger to be avoided at all costs. The appropriate reallocation of hospital resources to COVID‐19 treatments may leave patients without the traditional avenues for assessment and triage. Alternatively, one must entertain the idea that AHF hospital admissions are decreased due to decreased exacerbations. Stay‐at‐home orders could theoretically improve medication and dietary adherence.

The first step in determining how to address the issue is to determine the scope of the problem. Implantable, remote haemodynamic monitoring data from ongoing clinical trials (GUIDE‐HF, NCT03387813) analysed by time periods could ascertain if patients are maintaining goal haemodynamic parameters without hospitalization needs or are delaying care for worsening cardiac function. Analyses of international AHF registries would facilitate comparisons of national and regional hospital admission trends. Understanding the extent of reduced AHF hospitalization rates will be critical for the care of patients with heart failure in the COVID‐19 era.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Contributor Information

Zachary L. Cox, Email: zachary.l.cox@vumc.org

Pikki Lai, Email: Christine.lai@VUMC.org.

References

- 1. Nakamura M, Tanaka F, Nakajima S, Honma M, Sakai T, Kawakami M, Endo H, Onodera M, Niiyama M, Komatsu T, Sakamaki K, Onoda T, Sakata K, Morino Y, Takahashi T, Makita S. Comparison of the incidence of acute decompensated heart failure before and after the major tsunami in Northeast Japan. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1856–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tam CF, Cheung KS, Lam S, Wong A, Yung A, Sze M, Lam YM, Chan C, Tsang TC, Tsui M, Tse HF, Siu CW. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak on ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Washington Post. Patients with heart attacks, strokes and even appendicitis vanish from hospitals. April 19, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/patients‐with‐heart‐attacks‐strokes‐and‐even‐appendicitis‐vanish‐from‐hospitals/2020/04/19/9ca3ef24‐7eb4‐11ea‐9040‐68981f488eed_story.html (20 April 2020).

- 4. American College of Cardiology . American College of Cardiology urges heart attack, stroke patients to seek medical help. April 14, 2020. https://www.acc.org/about‐acc/press‐releases/2020/04/14/10/17/american‐college‐of‐cardiology‐urges‐heart‐attack‐stroke‐patients‐to‐seek‐medical‐help (20 April 2020).

- 5. Tennessee State Government . Tennessee novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) unified command. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/885e479b688b4750837ba1d291b85aed (22 April 2020).

- 6. Cox ZL, Lewis CM, Lai P, Lenihan DJ. Validation of an automated electronic algorithm and “dashboard” to identify and characterize decompensated heart failure admissions across a medical center. Am Heart J 2017;183:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE, Wasfy JH, Haneuse S, Shen C, Yeh RW. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program with mortality among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. JAMA 2018;320:2542–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]