We read with great interest the article ‘COVID‐19: what if the brain had a role in causing the deaths?’ by Tassorelli and co‐workers, in which the authors generate and summarize hypotheses as to how severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 may enter the peripheral and central nervous system and cause life‐threatening complications [1]. With this letter, we would like to contribute to this discussion by highlighting how different complications of COVID‐19 may result in damage to central and peripheral parts of the swallowing network leading to dysphagia in critically ill COVID‐19 survivors.

As demonstrated by a recent survey, dysphagia is a key concern in intensive care units (ICUs) [2]. According to the DYnAMICS trial, dysphagia affects more than 10% of patients after extubation, about half of whom remain dysphagic on hospital discharge [3]. Importantly, in this study, the incidence of dysphagia was even higher in specific subgroups, in particular in emergency admissions (18.3%) and in patients with acute neurological conditions, and was independently associated with overall disease severity and with increased length of mechanical ventilation (MV). Dysphagia in the critically ill has been identified as a key predictor of pneumonia, extubation failure, need for tracheostomy and prolonged MV, increased length of stay and overall adverse outcome and mortality [4].

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic is spreading worldwide with more than 3 million cases to date and growing numbers of ICU admissions. According to recent publications, around 5% of patients require ICU treatment with a high proportion in need of prolonged MV due to acute respiratory distress syndrome and vasopressor treatment for septic shock [5]. In addition to these conditions, which were identified as key risk factors for the development of critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy, other neurological complications such as stroke, encephalitis, skeletal muscle injury and Guillain–Barré syndrome have also been reported in COVID‐19 [6].

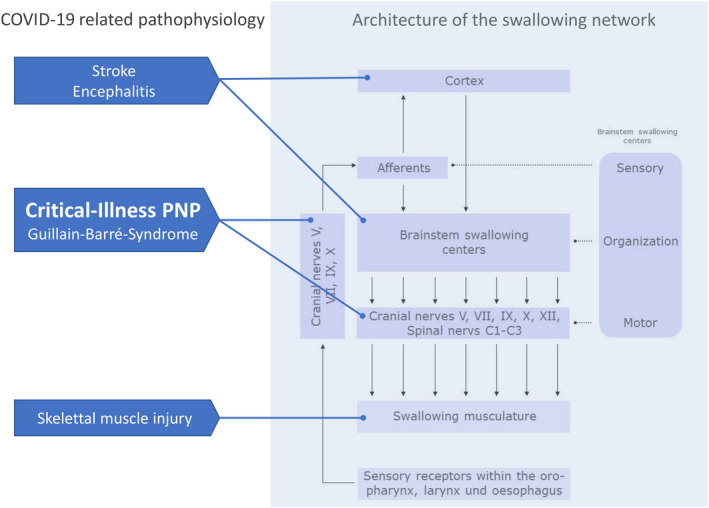

The act of swallowing is coordinated and executed by a widely distributed network that incorporates cortical, subcortical and brainstem structures as well as downstream peripheral nerves and muscles. As summarized in Fig. 1, all mentioned complications of COVID‐19 target this network at different levels and critically ill patients are therefore prone to dysphagia. Although this goes unnoticed and is of less relevance during the period of MV, dysphagia and related complications enter the scene when patients have been extubated or, in case of previous tracheostomy, the question of possible decannulation arises after successful weaning from MV. At this critical juncture, careful assessment of safety and efficacy of swallowing including management of pharyngeal secretions seems of utmost importance in COVID‐19 survivors, as these patients are, due to the severity of lung disease, particularly prone to suffering from respiratory complications subsequent to tracheal aspiration.

Figure 1.

Dysphagia due to COVID‐19‐related pathophysiology. The swallowing network has a multilevel architecture comprising cortical, subcortical and brainstem structures as well as peripheral nerves and muscles. Clinical sequelae and complications of COVID‐19 target different parts of this swallowing network. PNP, Polyneuropath.

The diagnostic workup in this context usually comprises an aspiration screening (e.g. water swallow test as implemented in the Bernese ICU Dysphagia Algorithm [4]) and, in case of screening abnormalities, a full dysphagia assessment, including, where appropriate, instrumental testing with fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing [4]. Importantly, the respective diagnostic steps are likely aerosol‐generating procedures, as patients, in particular those with severe dysphagia and aspiration, regularly cough during these tests. Because of the involved risks of virus transmission through aerosol emissions, dysphagia experts should wear appropriate personal protective equipment when approaching patients with COVID‐19. Subsequent to the initial dysphagia assessment and implementation of first therapeutic interventions like dietary modifications and simple compensatory maneuvers, more refined treatments should be decided on a case‐by‐case basis with the option to postpone these until the patient has tested negative.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

R.D. and T.W. declare no financial or other conflicts of interest. P.Z. reports (full departmental disclosure) grants from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International, B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd, Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestlé, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lily and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien and Nycomed outside the submitted work. J.C.S. reports (full departmental disclosure) grants from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International, B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd, Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestlé, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lily and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien and Nycomed outside the submitted work.

References

- 1. Tassorelli C, Mojoli F, Baldanti F, Bruno R, Benazzo M. COVID‐19: what if the brain had a role in causing the deaths? Eur J Neurol 2020; 27: e41–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marian T, Dunser M, Citerio G, Kokofer A, Dziewas R. Are intensive care physicians aware of dysphagia? The MAD(ICU) survey results. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44: 973–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schefold JC, Berger D, Zurcher P, et al. Dysphagia in mechanically ventilated ICU patients (DYnAMICS): a prospective observational trial. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 2061–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zuercher P, Moret CS, Dziewas R, Schefold JC. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Crit Care 2019; 23: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020; 77: 683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]