Abstract

The convoy model of social relations was developed to provide a heuristic framework for conceptualizing and understanding social relationships. In this Original Voices article, we begin with an overview of the theoretical tenets of the convoy model, including its value in addressing situational and contextual influences, especially variability in family forms and cultural diversity across the life span, but particularly in older adulthood. We also consider the contributions of the convoy model to the field of family gerontology by illustrating concepts, methods, and measures used to test the model, as well as its usefulness and limitations in addressing contemporary issues facing older adults. Finally, we discuss opportunities for innovation and application of the convoy model to the study of later‐life family relationships. In summary, we emphasize the benefits and inclusiveness of the convoy model for guiding current and future research to address challenges facing family gerontology now and in the future.

Keywords: aging families, convoy model, dynamic social networks

background

Successful developments in medicine, public health, and family planning have resulted in increased longevity and dramatic changes in family demographics that have, in turn, significantly influenced the size, shape, and function of the modern family (Antonucci & Wong, 2010). Such demographic shifts include declines in traditional marriage and child bearing; increases in delayed parenting, single parenting, same‐sex parenting, and sequential family parenting as a result of multiple marriages; and significant growth in racial and ethnic minority groups who often exhibit different family structures (Smock & Schwartz, 2020). Moreover, as a result of public health improvements, such as significant mortality reductions in childbirth and early childhood as well as breakthroughs in prevention and treatments of disease, people are living longer and are in better health than at any other period in history (Olshansky et al., 2012; Roberts, Ogunwole, Blakeslee, & Rabe, 2018). Despite how such sociodemographic shifts have changed the composition, function, and characteristics of families, the fundamental importance of close social support relationships to human growth, development, and well‐being remains across the life span. These relationships are especially significant in later life. A challenge for current family gerontology researchers is to incorporate new family forms and experiences while identifying factors that have traditionally supported and/or challenged family and individual resilience throughout the life course.

Families are often viewed as the core of human relationships; to be told “You are like family to me” is among the highest compliments we can bestow on nonfamily relations (e.g., Tannen, 2017). Families are often a source of support, socialization, and comfort throughout one's lifetime, but they can also be a source of negativity, ambivalence, trials, and tribulations (Antonucci, 2001; Connidis & Barnett, 2018). In this article, we consider how the convoy model of social relations informs later‐life family relationships, illustrating its usefulness for understanding older adults as individuals with a lifetime of experience but also as members of dynamic, linked, modern families. We begin by discussing the historical foundation and basic tenets of the convoy model, especially as they apply to family relationships in later life. We note the importance of integrating early life individual and family experiences with later‐life developments and changing times. Further, we emphasize that a convoy allows for movement beyond traditional, biological, or legal definitions of family. Notably, the tenets of the convoy incorporate all close relationships, an especially applicable advantage in light of the emerging importance of diverse, nontraditional, and increasingly complex family forms. Further, we consider measurement and methodological issues associated with the convoy model, elaborate its contributions to family gerontology, and outline how the convoy model can be helpful in promoting innovations for the future.

The Convoy Model of Social Relations

Historical background

Plath (1980) first used the term convoy to apply to the consociates or peer group with whom Japanese boys were raised. He used the term to refer to the mutual socialization among the boys who spend their childhood in age‐graded cohorts. Kahn and Antonucci (1980) extended Plath's use of the term as mutual socialization to develop an overall model that incorporates antecedents and consequences of social relations as well as a detailed specification of distinct elements of social relations (i.e., social networks, social support, and support satisfaction). At a time when social support was emerging as an important influence on a range of outcomes (e.g., health, well‐being), little was known about how to meaningfully, systematically, and scientifically conceptualize or measure important aspects of social relations (Antonucci, 1985; Knipscheer & Antonucci, 1990). Similarly, little was known about social support (i.e., the aid, affect, or affirmation people exchange) or specific factors that might predict the support an individual was likely to need or receive. The convoy model proposed that social relations could be predicted on the basis of specific, identifiable, antecedent factors such as personal and situational characteristics (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980).

At the time the convoy model was developed, social relations and social support were variously and ambiguously defined by objective and subjective characteristics, sometimes referred to as actual and perceived support. The convoy model was developed to incorporate these concepts into a coherent, inclusive model that clearly defines and measures the concepts of interest, thus providing consistency to permit the advancement of social relations science (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). An important goal of the convoy model was to provide a heuristic framework appropriate for people of all ages, from childhood through old age, that captured the nuance of different cultures and circumstances and also identified those factors associated with the causes and consequences of social relations (Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Birditt, 2013). The model was meant to be nonjudgmental and free of bias. Although it was assumed that there would be identifiable culture, age, or gender differences in social relations, a deficit model was not assumed a priori. This alone was innovative, in that most considerations of social relations assumed a Western, traditional family form and that anything that differed from that preconceived traditional perspective was deficient (Knipscheer & Antonucci, 1990).

Life span and life course theories

To better understand social relations across human life, both life span and life course theories were incorporated into the convoy model (Antonucci, Fiori, Birditt, & Jackey, 2010). Thus, to fully understand the background of the convoy model, we briefly describe the contribution of these two theoretical perspectives to the convoy model and how they are directly related to family in later life.

Life span theory was proposed by Baltes (1987; see also Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006) to describe an individual's intraindividual development over time. It emphasizes that development is a lifelong process, involves growth and gains as well as declines and losses, and is both multidirectional as well as multidimensional. Of particular importance in this theory is emphasis on plasticity, the idea that development of any sort is not set in stone but can change, and is influenced by many factors, including sociocultural experience as well as age‐graded, history‐graded, and nonnormative historical events (Baltes et al., 2006). Life span theory emphasizes that individual development over time is best understood through a multidisciplinary lens (e.g., cognitive, social, physical, psychological, economic). Important to this perspective is the notion that the present should be understood as building on or developing from the past, although not necessarily predetermined by it (Baltes, 1987). Rather than assuming that present circumstances or relations develop exclusively in contemporary time with no influence of past experiences, life span theory recognizes that early life experiences affect later‐life experiences. Two points are especially relevant to the family in later life: (a) intraindividual development occurs most often within the family context over an individual's life time, and (b) because that experience is lifelong, earlier individual experiences in the family of origin are likely to influence family in later life. The inclusion of a life span developmental perspective as part of the convoy model offered a new approach to understanding social relations both cross‐sectionally and longitudinally.

Complementing the life span perspective is the life course perspective, which focuses on how roles, organizations, social structures, and societal resources influence developmental trajectories (Elder, 1985; Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003; Hareven, 2018). Life course theory suggests that individuals are shaped by the situations, historical time, and geographical locations they experience over their lifetime. These situations include the timing (or individual age) of life transitions, individual and historical events, behavioral patterns, and role expectations. Environment and contexts influence what the situation is and how it is experienced at a particular age. The life course is an accumulating set of socially defined circumstances involving roles and responsibilities experienced by the individual over time; thus, individuals are intimately connected to the context in which they live (Elder et al., 2003). Individuals develop within families, which have a shared history and social context (Bengtson & Allen, 1993). An important aspect of life course theory is the recognition that lives are linked, shared by people who are close, often family with similar sociohistorical experiences (Elder et al., 2003). For example, the family is perceived as a microsocial group within a macrosocial context—a “collection of individuals with shared history who interact within ever‐changing social contexts across ever increasing time and space” (Bengtson & Allen, 1993, p. 470). Being embedded within a family may translate into dependence and/or codevelopment. Thus, incorporating the life course perspective into the convoy model recognized that social relations are sensitive to changing times and contexts for all ages. As we consider the family in late life, situational contexts are critical. As a prime example, the Great Depression created a shared history in that all families were affected by the economic circumstances of the time (Elder, 2018). The same can be said of the affluence of the 1950s (Galbraith, 1958) and the likely outcomes of the current COVID‐19 pandemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

In offering a framework for what influences the formation of social relations, the convoy model considers personal, life span characteristics (e.g., age, race, sex) while simultaneously recognizing the role of situational, life course characteristics (e.g., roles, norms, and behavior expectations that are imposed by external groups such as family, organizations, and community) as equally likely to influence an individual's social relations (Antonucci, 2001). Further, the convoy model does not privilege either personal or situational characteristics; both are recognized as having important independent and interactive influences on social relations (Antonucci et al., 2010). The convoy model has evolved as a multidisciplinary model that informs research across ages and contexts. It has particular value to the field of family gerontology, as it recognizes the mutual importance of constraint and agency through the lifelong influences and contributions of each family member. We turn next to outline the basic tenets of the convoy model and its application to the family in later life.

Tenets of the convoy model

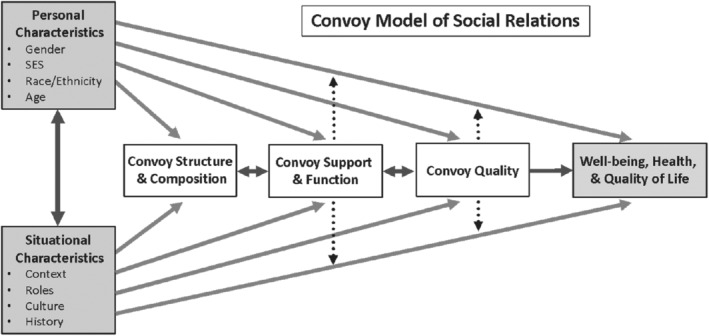

As illustrated in Figure 1, the convoy model posits that both personal and situational factors represent an individual's agency as well as constraints that in turn influence the individual's convoy of social support (Antonucci, 2001). Personal characteristics include individual factors such as age, sex, ethnicity/race, sexuality, socioeconomic status, income, and education. Situational characteristics refer to the context in which people live or have lived, for instance, cultural context or historical events. These also are associated with roles, norms, expectations, and organizations. Ideally, people create convoys to match their personal needs and experiences, but personal and situational characteristics play a role within circumstances that may promote or constrain an individual's ability to create the convoy that would be maximally beneficial to them.

Figure 1.

convoy model of social relations (adapted from kahn & antonucci, 1980 ; antonucci, 2001 ).

The convoy model builds from personal and situational characteristics to permit a more in‐depth assessment of factors determining and influencing the multiple dimensions of social relations. These multiple dimensions include structure, social support, and support satisfaction (Antonucci, 2001). The structure of social relations can be thought of as the objective characteristics of the network such as network size, composition (family or friend), contact mode (text or phone), and frequency. Social support, however, refers to the support actually exchanged, that is, given and/or received. This can be of various types, including aid or instrumental support, affect or emotional support, and affirmation or confirmatory support of an individual's values or beliefs. Finally, support satisfaction refers to individuals' assessment or evaluation of the support they receive. Regardless of the objective content of support given and received, there is a psychological dimension wherein people evaluate the support they receive or provide, determining for themselves whether they are satisfied with it or feel it is adequate to meet their (or the recipient's) needs. All of these separate aspects of social relations combine to influence the health, well‐being, and quality of life of the individual. Although Figure 1 presents a cross‐sectional visualization of the convoy model, all these tenets exist within a life span or life course framework that recognizes change over time. The convoy model thus also posits the longitudinal nature of the convoy, which changes and adapts as the individual ages, while typically maintaining stability as well.

Relation to other theories

Theories in the field of family gerontology have made significant contributions to thought about key characteristics and influences on older adults and their families (see Blieszner & Bedford, 2012, for a comprehensive overview). We highlight two that are prominently used in research addressing aging families, each of which takes a broad approach to the constructs at hand. With comparisons to intergenerational solidarity theory (Bengtson & Roberts, 1991) and socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999), we illustrate the relation of the convoy model to these influential theories that have advanced family gerontology in recent decades.

Early work by Bengtson and Roberts (1991) focused on intergenerational solidarity, arguing that intergenerational family cohesion is best understood through consideration of family affection and norms that, in turn, influenced frequency of association. The consequent sense of solidarity had implications for who would care for family members in need—often, but not exclusively, older family members. Whereas evidence supported these early positive characteristics and noted more intergenerational solidarity than discord, additional evidence revealed the need to include negativity, in the form of conflict, and ambivalence in order to fully capture family functioning (Bengtson, Giarusso, Mabry, & Silverstein, 2002).

Ambivalence challenged the assumptions of solidarity to suggest that positive sentiments coupled with simultaneous irritations better reflect the nature of relationships between generations (Lüscher & Pillemer, 1998). Connidis and McMullin (2002) further elaborated the concept of ambivalence to highlight how social structure and individual agency concerning family situations must be examined simultaneously to better understand the nature of family relations over the life course. For instance, intersecting hierarchies of class and gender may produce very different and ambivalent situations for working women (professional vs. working class) faced with caregiving responsibilities of an aging parent. In other words, positive and negative aspects of relationships arise through the interplay of structural opportunities and constraints on individual action. Informed by this work, the convoy model carefully assumes neither positivity or negativity, but rather assesses multidimensional convoy quality, leaving room for individual interpretation of exchanges from specific network members and recognizing that relationships with the same people can be positive, negative, or both (Antonucci, 2001). Further, the model incorporates the fact that positivity or negativity in relations can change over time, and that perceptions can differ between people (i.e., one spouse perceives positivity while the other perceives ambivalence).

Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST; Carstensen et al., 1999) posits that as people age, they narrow the focus of their emotional contacts to include mostly close family. Younger people, Carstensen et al. (1999) argue, seek a wider array of social interactions because they view the future as unlimited; but when confronted with a more restricted future time frame, either because of old age or life‐threatening illness, people have a tendency to restrict their emotional outreach to only close relations (Carstensen et al., 1999). SST provides an interesting perspective on how and why older adults focus their attention primarily on close family members as well as the emotional components of social interactions. Some constricting of relationships may result from individual changes, perhaps due to physical or cognitive limitations, or to changes in norms and expectations that result in relationship constrictions; such changes may be particularly salient as an individual nears the end of life. The convoy model, however, suggests that such narrowing is not necessarily universal (Antonucci et al., 2013). Instead, social relations likely vary for older adults depending on various personal and situational characteristics.

In contrast to other theories of family gerontology, the convoy model incorporates multiple factors into a single framework. Further, it offers explanations for which types of relationships are most needed by people in specific circumstances. The convoy model considers social relations in the context of long‐term relationships as well as the personal and situational factors that influence them (Antonucci, Birditt, Sherman, & Trinh, 2011). The convoy model acknowledges that families and support networks are dynamic and often respond to demographic, cultural, and psychosocial trends (Antonucci et al., 2013). Hence, the convoy model allows for specificity to the situation, needs, and preferences of older adults and their families.

Measuring the Convoy: The Hierarchical Mapping Technique

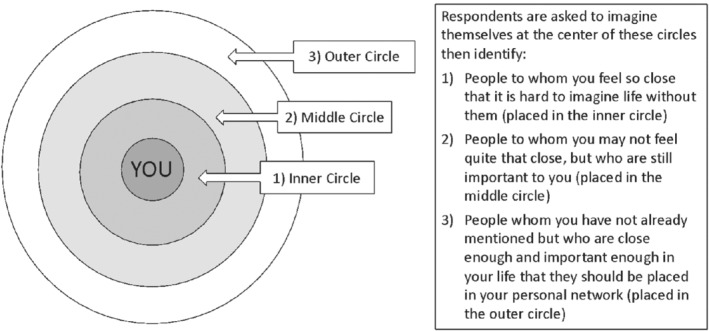

The aforementioned theoretical assumptions are especially useful for identifying how to measure the various dimensions of social relations. The primary assessment method of the convoy is the hierarchical mapping technique (Antonucci, 1986), which is designed to measure network structure (e.g., size, composition) and relationship closeness (i.e., intimate vs. weak ties). The hierarchical mapping technique first presents a series of three concentric circles, with the word you at the center (Figure 2). Respondents are then asked to imagine themselves at the center of the circles and to list the names of important people in their lives according to how close they feel to them. The inner circle represents “people to whom you feel so close that it is hard to imagine life without them.” The middle circle represents “people to whom you may not feel quite that close but who are still important to you.” Finally, the outer circle represents “people whom you have not already mentioned but who are close enough and important enough in your life that they should be placed in your personal network.” Summed together, the three circles represent the overall convoy of the individual; or, when examined separately, they represent distinct levels of closeness within the overall convoy.

Figure 2.

the hierarchical mapping technique (adapted from antonucci, 1986 ).

This method of mapping the convoy is particularly valuable across ages and contexts given the universal nature of this assessment tool. The simple and straightforward nature of the hierarchical mapping technique is readily understood by individuals across the life span, making it a valuable measure for use by people of different ages (or the same individuals longitudinally). The hierarchical mapping technique has been successfully used from middle childhood through late older adulthood (Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Webster, 2019; Manalel & Antonucci, 2019). Moreover, this method easily and successfully translates to different cultural or national contexts and has been used in the United States among diverse groups of older adults including Whites, Blacks, Arab Americans, and Hispanic Americans (e.g., Ajrouch, 2005; Ajrouch, Antonucci, & Janevic, 2001; Winston et al., 2015), as well as in Japan, Mexico, Lebanon, France, and Germany (e.g., Antonucci et al., 2001; Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Abdulrahim, 2014; Fuller‐Iglesias & Antonucci, 2016).

Of central focus is how the convoy model allows for the study of older adults in the context of their social relations but without the constraints of imposing traditional social norms, such as the assumption that one occupies any particular role or is close to another because of that role (Antonucci, 2001). No family, community, or national norm is imposed; rather, the individual identifies closeness with whomever they wish. This may include people to whom they are biologically or legally related or not, people with whom they have primarily positive relations, and also those with whom they have negative or ambivalent relations. People may identify convoy members whom researchers would readily expect, such as close family members or friends, but they may also identify unexpected convoy members, such as a deceased spouse, pet, or infant child. Moreover, information can be gleaned from who is omitted from a convoy, such as a married person not including their spouse. To further understand the meaning of who is (or is not) included in a convoy, pairing the mapping tool with further quantitative and qualitative probing provides important insights into the meanings attributed to individuals' social and family relationships. The hierarchical mapping technique effectively identifies the individual's personal convoy, thereby providing a foundation for measuring multiple dimensions and contexts of social relations across age groups and cultures.

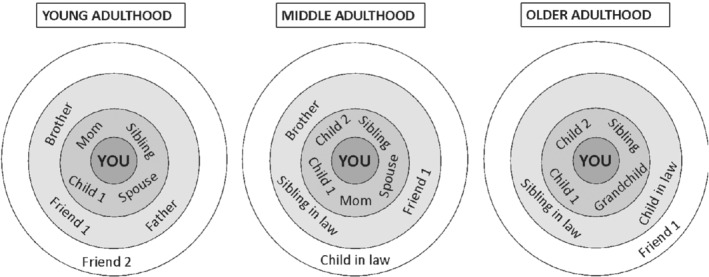

After identifying the membership and closeness of the convoy, we can then assess various structural characteristics. Figure 3 presents an example of the convoy composition for a hypothetical individual's convoy and the normative changes within that convoy composition as they age (based on data from the Survey of Social Relations; Survey Research Center, 2015). Although there is great interindividual variability in convoy composition, Figure 3 demonstrates common patterns in the data (Antonucci et al., 2013), such as an inner circle consisting primarily of nuclear family members, the overall convoy size decreasing with age, naturally occurring changes in the convoy (e.g., due to the birth of children or death of parent), and consistency and stability in placement of convoy members over time. For instance, for the individual in Figure 3, we can identify fluctuation in total network size over time from eight in young adulthood to nine in middle adulthood and seven in older adulthood. Moreover, changes in the size of the individual circles indicate patterns of closeness across the life span, with the inner circle the largest and the outer circle the smallest consistently. The individual in Figure 3 primarily relies on family members in their convoy and maintains relative consistency in the membership and placement of their convoy members across time, yet changes can be observed over the life span, such as the addition of children and in‐laws and the loss of parents or friends. As seen here, the hierarchical mapping technique serves as a starting point for an array of additional factors that a researcher may wish to assess about an individual's convoy.

Figure 3.

example of convoy change over time.

Note. Hypothetical figures based on data for mean circle size and composition in 2015 (Survey Research Center, 2015) synthesized to represent a hypothetical average individual.

Further probing could identify specific support and satisfaction characteristics of relationships with each convoy member. For instance, dynamic methodologies and complex designs are needed to examine the varying types of social support exchanged within convoys, such as different types of tangible (e.g., instrumental help, financial) and intangible (e.g., emotional or affirmational) support (Antonucci et al., 2011). An older adult may rely on some convoy members for instrumental support or direct care but on other convoy members for attachment or emotional fulfillment. Changing family structures and societal norms make this nonbiased assessment method especially critical. The researcher or practitioner is free to focus on whichever aspect of social relations is of interest, and in turn, the support needed, exchanged, and evaluated is assessed based on the individual's perception.

The Convoy Model and Later‐Life Relationships

The convoy model provides conceptual and methodological direction that benefits approaches to the study and understanding of older families. In particular, the conceptualization of a convoy positions the individual as the center of his or her social relations, and the method of identifying convoy members facilitates an organic, rather than predefined, means of defining network membership. This approach enables the identification of social relations by people of all ages, including older adults, and allows for the recognition of finer categories based on variables of interest (e.g., young‐old versus old‐old). In addition, the convoy model allows for older adults to initiate their perspective on and definition of social relations. Thus, the contributions of the convoy model include its facility to ensure the comprehensiveness of social relations, flexibility in defining kin, and adaptability across cultures.

Comprehensiveness

Although some theoretical perspectives in family gerontology benefit from a targeted focus on a specific family relationship or family function, an important contribution of the convoy model is that it provides a broad, comprehensive perspective on social relations. The convoy model permits a macro‐level view and examination of all components and processes involved in an individual's close social support network, including, but not limited to, family ties. Moreover, it allows for an understanding of the role and position of family relationships in the older adult's broader set of social relationships. The comprehensiveness of social relations using the convoy model is perhaps best illustrated by recognition of multiple dimensions: structure, type, quality, and sources of support (see Figure 1). Older adults face loss as well as growth in who is part of their family. For instance, spousal loss through death or divorce increases with age, and the likelihood of younger family members may arise through the birth of grandchildren. The convoy model provides an all‐encompassing framework for these complex and dynamic dimensions as individuals grow older. Adapting strategies to address the changing nature of family ties helps maximize resources available through these relationships as they connect the past to the present (Allen, Blieszner, & Roberto, 2011).

Attending to the multiple dimensions of social relations provides a framework for overcoming limitations inherent to universalizing tenets, eschewing a one‐size‐fits‐all approach to the study of family social relations. A case in point is the multiple dimensions of social network structure. For example, in a recent analysis, Antonucci et al. (2019) showed the ways in which network structure varies by age and closeness similarly and differently across two cohorts of adults aged 50 and older, 25 years apart (from 1980 to 2005). Networks were examined in a systematically nuanced way by including the entire network as a whole but also parsing out levels of closeness as an inherent element of an individual's network. Findings suggest that despite known changes in population demographics between 1980 and 2005, some fundamental elements of social connectedness transcend time and place for older adults. For instance, across both cohorts of older adults, network composition (i.e., proportion of the network that included spouse, children, siblings, and friends) was similar. Further, older adults were most likely to place their children in their inner circle in both cohorts, showing that children remain important and close for older adults.

Although similarities were detected, some elements of networks were different. For example, older adults reported more frequent contact with their convoys in 2005 than in 1980, which may be related to the increased availability and adaptation to methods of communication (e.g., cell phone, social media, video chat). The identification of both similar and different patterns in multiple dimensions of convoy structure contributes to the broader field of family gerontology by facilitating examination of older adults' networks in ways that accommodate change but also detect stability in form and function of social relations. The fact that older adults continue to report support networks that indicate close ties to family provides key insights that contradict the popular view of the declining importance of family and overall social connectedness while also making room for consideration of new qualities of social relations in old age (e.g., communication technologies) not existing in decades prior. Both the conceptual and the methodological strengths of the convoy model illustrate the fundamental role of families regardless of how sociohistorical contexts change.

Defining Kin

It is essential to note that definitions of kin are not universal. For example, different cultural and ethnic groups define kin distinctly (e.g., Taylor, Chatters, Woodward, & Brown, 2013). Because the convoy model does not predefine categories of people as network members, it allows for older adults to incorporate multiple relationship types at varying levels into their social networks. Dilworth‐Anderson and Marshall (1996) aptly noted the need to include nonkin in family research, especially among diverse and minority groups. Although kinship definitions may vary at any point in the life span, this may be especially important in later life. Older people often must adapt to family changes and losses, thereby necessitating a reinterpretation of definitions and meanings of kin. Promoting an extended family member to a close support network member or creating fictive kin by redefining friends as family are illustrative examples (Allen et al., 2011).

The convoy model is adept at allowing for such flexible definitions of family and accounting for the involvement of both kin and nonkin in the social support network because the individual defines not only the membership of their convoy but the closeness of those members as well. Prior research has noted that people of different racial groups have distinct convoy compositions, particularly with regard to family (especially extended) involvement (e.g., Hernandez, 2017); although with age, cultural differences in family involvement may decrease (e.g., Ajrouch et al., 2001). Research explicitly examining fictive kin found that Black individuals were more likely to incorporate fictive kin into their social support network than White individuals (Taylor et al., 2013), highlighting the need to examine situational distinctions in the definition of kin and incorporation of nonkin into the convoy. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender (LGBT) men and women have particular lifetime experiences that influence their patterns of social support over time and are less likely to have traditionally defined family members as they age (Reczek, 2020), thus creating convoys often involves more friends and nontraditional kin, negotiated within existing legal structures of who is defined as family. Recent work applied a convoy model framework to study the support networks of older gay men and similarly emphasized the value in broadening definitions of kin for LGBT elders who often develop families of choice (Tester & Wright, 2016). In sum, the convoy model facilitates inclusion of multiple relationship types into networks as defined by older adults, including diverse definitions of kin in various contexts.

Cultural Contexts

The convoy model also facilitates understanding of older families across cultures and including diverse family forms. Importantly, cultural values, which influence the feelings of family obligation and the extent of family involvement within social networks, may be accounted for using the convoy model. As family research expands its global reach, a growing literature recognizes intergenerational relationships and the universal as well as distinct needs of older adults in families cross‐culturally (Carr & Utz, 2020; Trask, 2009). The roles of older family members may vary across racial, ethnic, and cultural contexts.

In emphasizing personal and situational characteristics as influences on the convoy (Antonucci et al., 2013), the convoy model is able to address race, ethnicity, and culture, and how these affect the structure, quality, and function of social support networks. In an examination of widowhood and convoy characteristics in France, Germany, Japan, and the United States, Antonucci et al. (2001) found that widowed individuals had smaller social networks in France and Germany and less contact frequency in Japan, but there was no association between widowhood and network characteristics in the United States. It may be that widowhood related to social network characteristics in each country except the United States because being widowed in the other countries may carry with it greater role expectations or role restrictions that relate to behavior and interactions with others. These socially determined expectations could influence both the individual's ideas about what is expected as a widow and how others respond to the individual (Antonucci et al., 2001). Although this study did not specifically identify the family composition of those social networks, it indicated cultural differences in the social convoys linked to widowhood status. These cross‐national differences in convoy structure associated with widowhood indicated differences in family dynamics in older adulthood that are likely due to cultural differences in the meaning and/or role of the widow given that all four were wealthy countries. It is clear that convoys of social relations have both different and universal elements across cultures.

Cultural similarities that suggest universal elements in the composition of later‐life social networks were recently identified by Ajrouch, Fuller, Akiyama, and Antonucci (2017), who compared convoy characteristics between Japan, Lebanon, Mexico, and the United States. Specifically, in all four countries, increased age was associated with reporting a greater proportion of children in one's network, and children were more likely to be placed in the closest circle. These similar patterns across nations suggest a common feature of family networks that may reflect that a universal characteristic of human bonding involves keeping children close (Rossi & Rossi, 1990), even in later life. The convoy model's emphasis on distinguishing relationship types in the study of social relations provides opportunity for identifying such patterns.

In sum, these findings provide some initial insights into better understanding cross‐cultural universals and differences in aging family dynamics. Although various challenges exist to furthering the understanding of aging families across national contexts, we suggest that the convoy model provides an ideal framework for cultural comparison. The contributions of the convoy model allow for older individuals to be the focal person at the center of their own social world. A convoy framework could help shift from a perspective focusing on older adults as dependent in families to one of older adults having diverse needs, roles, and abilities to contribute to their family convoys. It remains a challenge to expand the research on aging and family dynamics in understudied racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Native Americans) and contexts (e.g., developing countries); however, given the global demographics of aging, it is essential to focus research efforts on cultural variation in family dynamics in later life. Across time and place, within and across families, the ease of use for distinctive later‐life situations makes possible a more in‐depth understanding of the extended life span within families.

Methodological Approaches Related to the Convoy Model in Later Life

In addition to the aforementioned development of the hierarchical mapping technique that facilitates neutral assessment of the convoy itself, the convoy model also contributes to methodological advancement by providing a framework for defining what to measure and how to measure it (Antonucci et al., 2013). The tenets of the convoy model inform decisions related to methodology and analysis, but it is also the case that commonly used methodologies contribute to the understanding and application of the convoy model. Such methodologies have been developed with populations across the life span, yet have paid special attention to the context of later life. Here we highlight methodological approaches related to aging and late‐life relationships in three key areas: interindividual variability, intraindividual variability, and reciprocity.

Interindividual Variability

A prevalent methodology used in research from a convoy model perspective focuses on understanding interpersonal differences in convoys, providing a mechanism for assessing the heterogeneity of older adults and their families. As individuals age, there is increasing variability between them in terms of their physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development and well‐being (Baltes et al., 2006). This increasing heterogeneity poses challenges for researchers who seek to understand patterns, processes, and mechanisms of aging, including older adults' social well‐being (Lowsky, Olshansky, Bhattacharya, & Goldman, 2014). Given that the convoy model highlights personal characteristics as an essential feature in determining individual differences in convoys, an ongoing body of research has employed designs comparing individual differences in convoy composition and effects among older adults (e.g., Antonucci et al., 2011; Antonucci et al., 2019; Fiori, Antonucci, & Cortina, 2006). Particularly salient among these are studies designed to identify interpersonal variability in personal characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity (e.g., Ajrouch et al., 2001; Ajrouch, Blandon, & Antonucci, 2005; Antonucci et al., 2019). In addition to interindividual variability based on personal characteristics, this line of research takes a person‐centered approach to analysis, permitting, for example, the identification of interindividual differences in typologies of convoys and examination of the support exchanged at subjective and objective levels. This is especially valuable in understanding differences between aging individuals in terms of the structure, function, and quality of their family (and friend) networks. For instance, a family gerontologist might employ a convoy approach to examine differences in instrumental support sources between older men and women based on their parental status. The convoy model advocates assessment of differences between individuals on any specific characteristic or variable of interest, and by doing so, it serves as an excellent framework for understanding family differences in later life.

Intraindividual Variability

In addition to promoting a focus on interindividual variability, the convoy model also posits intraindividual variability in convoys, specifically with regard to change over time in individuals. Time is thus a key methodological focus of the convoy model and should be examined in the short and long terms. Over the long term, the convoy model suggests that there is value in understanding lifelong shifts in convoys over years. Longitudinal methods and modeling of trajectories of change over time have emerged to identify such long‐term within‐person change (i.e., Nesselroade & Ram, 2004). For instance, numerous recent studies have employed multilevel or growth modeling to examine the implications of convoy characteristics, functioning, and quality over time (e.g., Antonucci et al., 2019; Birditt, Jackey, & Antonucci, 2009; Mejía & Hooker, 2015; Pan & Chee, 2019). For older adults in particular, such methods can help determine whether the amount of support available from family or others shifts over time with age and also examine the implications of such changes for that individual. A future direction extending such lines of inquiry could be examining intrafamilial changes within family convoys over time for aging adults.

The convoy model also supports an examination of time in the short term (i.e., patterns of interpersonal support over the course of hours, days, or weeks). Given the many discrete support exchanges that are important to capture within the daily or weekly functioning of a convoy, it is valuable to employ experience sampling methods to explore the variability of daily social support interactions instead of a onetime snapshot. Experience sampling (also referred to as ecological momentary assessment) is an intensive method that asks participants to report on their thoughts, experience, or feelings on numerous occasions over time in their everyday lives (Hektner, Schmidt, & Csikszentmihalyi, 2007). Using such methods, advancing our understanding of support provision on a daily basis can be achieved by having convoy members record the type of support they provide to or receive from other convoy members on a momentary basis throughout the day or in bursts over a short time period. For example, recent research has employed experience sampling to examine older adults' daily interactions with close social partners (e.g., Chui, Hoppmann, Gerstorf, Walker, & Luszcz, 2014; Mejía & Hooker, 2015; Zhaoyang, Sliwinski, Martire, & Smyth, 2018). Moreover, such methods can be valuable to gaining a better understanding of specific situations in the later‐life convoy, such as exploring the experiences, functioning, and well‐being of primary family caregivers of older adults with dementia (e.g., Pihet, Passini, & Eicher, 2017). Such findings could be extended beyond the caregiving dyad to further explore social support within the older adults' broader convoys. For instance, if dyadic or socio‐centric network analysis methods were to be combined with experience sampling methods, incredibly rich data could be gathered on the reciprocal interconnections in late‐life families as well as the functionality and quality of those convoy connections. Thus, when integrated with a convoy model perspective, experience sampling methods can glean complex knowledge about the daily support function and needs of older adults as well as their entire convoy.

Reciprocity and Aging Convoys

The tenets of the convoy model make clear the complexity of relationships, encouraging attention to dynamic interactions among and between network members (Antonucci, 2001). This is especially noteworthy given that older adults often have a lifetime of relationships (e.g., siblings, spouse, children), as well as newly emerging relations (e.g., fictive kin, grandchildren). It is, therefore, critical to be able to assess new means of forging and maintaining relationships as well as how these influence the type and quality of relations, and in turn, well‐being. A key facet of the convoy model is the recognition of reciprocal exchanges between convoy members (Antonucci et al., 2011). Social support is reciprocal in nature, consisting of giving and receiving for all individuals involved, yet the level and function of reciprocity varies across ages and contexts (Antonucci & Jackson, 1990). For instance, within the parent–child relationship, the balance of reciprocity is perceived to shift across the life course with children receiving greater support than they give until their parents reach late life (Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso, & Bengtson, 2002). A lifetime notion of reciprocity is incorporated into the concept of a support bank, which is the idea that people recognize that the provision of support earlier in life to a close other may qualify them to receive support when needed later in life (Antonucci, 2001). As families age, challenges such as role reversal and late‐life dependency emerge that may test the notion of the support bank as well as the strength and functioning of an older adult's convoy. Recognizing the significance of reciprocal interactions in social relations, the convoy model advocates for sampling multiple age groups and multiple relationships in the quest to better understand social relations and well‐being within families and across generations.

The convoy model emphasizes the reciprocal and dynamic nature of the provision and receipt of support over the lifetime (Antonucci et al., 2011), thus employing research methodologies that account for reciprocity is key especially within family gerontology. By integrating methods that acknowledge the reciprocity inherent in social support relationships (Wrzus & Wagner, 2018), we can develop a more nuanced and complete understanding of convoy dynamics as people age. The use of dyadic analysis methods, such as actor–partner interdependence modeling, has proved valuable in identifying the reciprocal dynamics of relationships (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), with significant implications for understanding social support within convoys. Studies using dyadic analysis methods have identified the reciprocal effects of support within the marital and parent‐child relationships for well‐being in mid‐ to later life (e.g., Birditt, Miller, Fingerman, & Lefkowitz, 2009; Ermer & Proulx, 2019). For instance, by collecting data from both the individual and core convoy members, researchers have examined concordance between perceived support (by the respondent) and enacted support (by convoy member), which permits a better understanding of the reciprocity of social support in middle to older adulthood (Birditt, Antonucci, & Tighe, 2012). The increased availability of longitudinal data is making the possibility of further exploring the reciprocal dynamics of the support bank increasingly feasible.

In terms of research on aging families, future studies will benefit from applying a convoy framework to understanding intrafamilial change over time. Although the aforementioned dyadic research is burgeoning in the field of family science (e.g., Lyons & Sayer, 2005), recent developments in socio‐centric network analysis could be an important next direction in later‐life family research. In contrast to the typical egocentric methods of the convoy model, in which methodologies focus on the individual at the center of the network, socio‐centric methods focus on the network as an entire unit, and the analysis focuses on interconnections in the larger network (Knoke & Yang, 2019). Such socio‐centric network analysis methods could permit a better understanding of changes in the family convoy and its interconnections over time, and could document consistencies and disparities between an individual's self‐identified convoys within families. Moving beyond the individual level will be essential for understanding late‐life family relationships, as they have become increasingly complex and dynamic. Moreover, as it becomes increasingly clear that family dynamics in later life may challenge the notion of reciprocity, it will be key to determine whether reciprocity between some connections within a given convoy may compensate for the lack of reciprocity in other connections.

The convoy model highlights the importance of developing and utilizing methods that can address inter‐ and intraindividual change in convoys, the situational and personal circumstances that influence convoys, and the outcomes affected by convoys across the life span but especially in later life. In the future, longitudinal applications of the convoy model will be especially relevant to understanding changes in aging families over time. Moreover, it is imperative to go beyond the individual level, with dyadic, triadic, and socio‐centric network methods that collect and analyze data from both the older adult and their convoy members.

Opportunities for Future Innovation

The convoy model has proved a valuable conceptual framework for the field of family gerontology. It has been successfully used to further understanding of social relationships across the life course, including later life. As the field of family gerontology moves into the 2020s and beyond, it is useful to consider how the convoy model might be helpful in addressing challenges we face due to changing times and evolving historical contexts. In particular, the convoy model will continue to be especially useful for understanding late‐life families because of its flexibility in accounting for demographic and societal shifts, cultural variability, and dynamic intergenerational connections. As we look to the future, we anticipate that the convoy model will promote innovation and applications to better understand and foster quality of life among aging families. Four illustrative examples of potential future directions for how the convoy model can be used to address emerging challenges include (a) changing family forms in later life, (b) the role of weak ties in later‐life families, (c) technology and new ways of connecting, and (d) prevention and intervention opportunities.

Changing Family Forms in Later Life

Families evolve and change over time, and their form and function are affected by what is going on around them in the larger society (Allen et al., 2011; Bengtson & Allen, 2009). The convoy model, with its attention to situational factors and relationship type, is receptive to changing family forms in later life including step and blended families (Sherman, Webster, & Antonucci, 2013), LGBTQ families (Reczek, 2020), childless elders (Klaus & Schnettler, 2016), and fictive kin (Taylor et al., 2013). Of central relevance to the future of family gerontology will be a better understanding of how families evolve as life expectancies increase and birth rates decline (Smock & Schwartz, 2020). As family form and function change at the broadest level, these demographic changes mean that biological families tend to be smaller. As a result, older adults will increasingly hold central roles in their families and create new meaning in their relationships (Blieszner & Bedford, 2012). Further, family changes in later life include increased opportunities for intergenerational relationships as well as shifts in living arrangements, such as living apart together (Carr & Utz, 2020). We argue that even though the form of families may change during later life, their fundamental function of providing support has not; however, theorists and researchers need to adapt concepts and methods to best understand late‐life family functioning. The convoy model serves as a malleable heuristic to inform innovations in research and application to address changing family forms now and in future decades.

With increased recognition of later‐life family contexts across ethnic groups within the United States and across the globe, a valuable direction to which the convoy model can contribute new insights is in furthering research on cultural diversity in the field of family gerontology. For instance, in a role‐based model of social support, multigenerational family dynamics across cultural contexts may be overlooked if a researcher assumes that parent–child is the primary dynamic in the family, when the grandparent–grandchild, extended family, or fictive kin dynamic may also (or instead) be central. Further, as many families experience divorces and remarriages; challenges such as substance abuse; or absence due to military service, incarceration, or distant employment, the older generation is sometimes the most consistent adult presence that younger generation members experience (Carr & Utz, 2020). Using the convoy model to identify long‐term resources that are most helpful for meeting the needs of multiple family members, including older and younger family members, will help identify resources that are available and needed by each member of the family and that should be supported by policy, legal institutions, and society in general. It may also be useful in identifying programs that can be designed to optimize resources and minimize limitations or risks of the increasingly common multigenerational family. Although families have always been resilient and responsive to changing sociodemographics, the convoy provides a conceptualization that will continue to adapt over time as a variety of factors influence the family form, functioning, and experiences of aging individuals and their families.

Role of Weak Ties

A key but often overlooked aspect of the convoy model is its recognition of and potential ability to examine weak ties. The strength‐of‐weak‐ties proposal (Granovetter, 1983) substantially advanced thinking about social networks by drawing attention to the centrality of distant relationship types that ultimately serve as resources to access myriad opportunities. The convoy model differentiates the level of closeness of network members who are considered important to the individual, with the third level of closeness representing weaker ties. This third level (i.e., outer circle) of the concentric circle diagram (see Figure 2) used to measure an individual's convoy provides rich opportunities to examine the role of these weaker ties in older adults' social relations and overall well‐being.

Later‐life families exist in larger contexts. Relationships that older family members develop and maintain include those outside of family and identified through various avenues such as community organizations, formal service providers, and even social media (Ajrouch et al., 2019). The ability to recognize and identify weak ties as a critical part of an older adults' convoy represents a new direction for better documenting the form and function of social relations. Better understanding of the role of weak ties within family convoys, and in addition to family boundaries, has the potential to reveal a diversity of pathways of well‐being. In a recent study, Huxhold, Fiori, Webster, and Antonucci (2020) longitudinally examined weak ties among people age 40 years and older. They found that having a greater number of weaker ties earlier was associated with having more close ties over a period of 25 years. They also found that the number of weak ties earlier in life was associated with both more positive affect and less depressed affect over time. In another study, Kemp, Ball, and Perkins (2013) modified the convoy model specifically in the context of assisted living with a goal of better understanding how formal and informal caregivers interact and work together. For each focal care recipient, the researchers observed and interviewed multiple informal (e.g., adult children, spouses) and formal (e.g., assisted living staff, outside medical professionals) caregivers and then combined data from multiple sources to develop a synthesized picture of the functioning of the care convoy. Through this method they identified the important function of weaker ties who may not have been identified solely with the usual hierarchical mapping technique. This brings to light the importance of considering other methods to pair with or expand the hierarchical mapping technique to enable researchers to identify less central ties who play significant roles in the lives of older adults.

Future focus on the prominence of weak ties for older adults in the context of their families and beyond could also address the challenge of overcoming age‐segregated societal structures and/or the expectation that older people want to or should decrease their social ties. Western cultural norms, in particular, have perpetuated a societal structure that separates role expectations according to age (Riley, Kahn, Foner, & Mack, 1994). For instance, by these norms, formal education is an expectation reserved primarily for youth, workforce participation is primarily reserved for middle‐aged adults, and leisure activities an expectation for older adults. Weak ties provide opportunities to overcome normative role behaviors because they potentially link older adults to opportunities outside of their family units (e.g., older people attending college classes in their community, learning a new language, participating in Elderhostel programming). Further, weak ties may be particularly beneficial for older adults who live far from immediate family. In such cases, neighbors or new relationships may emerge as key during an emergency situation because of health obstacles that prevent an older adult from leaving the home (Greenfield, 2016). The quick development of neighborhood networks to assist at‐risk neighbors during the current COVID‐19 pandemic is a case in point (Simon, 2020). Weak ties will increasingly become central avenues of opportunity as demographic transitions influence family forms. Beyond using the outer circle of the convoy to indicate weaker ties, a fruitful new direction might be to add a fourth concentric circle to the hierarchical mapping technique that asks to include individuals whom the older adult may not think of as important or close but who nevertheless are part of daily life. Perhaps another way to address this could be adapting the hierarchical mapping technique to assess frequency of contact, with the inner circle representing people with whom an individual has daily contact, the middle circle representing weekly, and the outer representing monthly.

Technology and New Ways to Connect

Technological advancements are fundamentally changing social relations and the ways families relate to one another. Internet communication technologies and smartphones have introduced a new mode through which social relations occur, facilitating connections between individuals wherever they are instead of requiring presence at specific locations. Technology is revolutionizing communication patterns, profoundly changing how we connect to family members and friends. Advances in communication technology and social media offer new ways for older adults to establish social connectedness with family and friends (e.g., Czaja, Boot, Charness, Rogers, & Sharit, 2017). This may be particularly relevant for families separated by geographical distance, especially in the case of international migration. Technology creates new opportunities for providing care from afar, opening up new areas for examining intergenerational family ties. Further, new technologies have spawned new forms of shared meaning making using innovative modes of expression beyond verbal language, yet the range of technological access and ability among older adults creates a disparity, with a large portion of older adults left out from such shared storytelling (Barbosa Neves & Casimiro, 2018). The convoy framework could be used to better understand how transnational family ties are sustained with the support of new technologies and the effects this type of social connection has on the well‐being of older adults and their families. Although we are only beginning to understand how closeness of relationship influences the use of technology to communicate (e.g., Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Manalel, 2017), the convoy model will be extremely useful in identifying social networks that arise because of connections through technology and the potential inequalities that exist within and across families. For instance, including questions that inquire as to whether a convoy member lives in the same country as the older adult might be included. Testing the effects of personal and situational characteristics have on the prevalence of transnational networks would provide novel insights into potential inequalities within families and across older adults who have transnational family members.

Recent research has demonstrated that older adults successfully forge new relationships using social media, at least in Western countries, in addition to maintaining existing or rekindling old relationships (Rogers et al., 2019). Preliminary data indicate that quality of relationship influences mode of communication and may actually enhance positive relationships but exacerbate negative relationships (Antonucci et al., 2017). The ability to hone in on networks that older adults create and sustain through smartphones offers the ability to better understand new ways of having and enacting social relations during later life. Some practitioners laud the use of technology as a means to keep older adults connected, whereas others fear that it further isolates them (Barbosa Neves & Casimiro, 2018). The convoy model can be adapted to guide research to examine how technology influences social relations within the family and whether increased technology use improves or worsens the convoy connections of older people. For example, using the convoy heuristic to measure a smartphone or social media convoy would identify these forms of social relations, which could then be examined in the context of personal and situational factors as well as their effects on health and well‐being. Ultimately, these new convoys may provide innovative insights into developing prevention and intervention programs that maximize the well‐being of older people, their families, and other social relations.

Prevention and Intervention

Researchers using a convoy model framework have typically engaged in primary research studies, yet there are important avenues for applied research using the convoy model, particularly with regard to prevention and intervention. An important applied area of inquiry to pursue is the study of effective ways to intervene to promote positive convoy functioning and/or prevent dysfunctional interactions within convoys. For instance, a convoy model framework would be beneficial to the design of a study seeking to reduce loneliness among older adults by taking a comprehensive approach to understanding availability of social support (i.e., the structure of the older adult's social convoy), type of social support available (i.e., the extent to which an older adult receives aid, affect, and affirmation), and satisfaction with social support (i.e., the older adult's perception of the quality of support they are receiving). By comprehensively assessing each of these dimensions, researchers can determine for which level to design an intervention, for example, to attempt to reduce loneliness (e.g., perhaps loneliness is not due to convoy size but to a lack of affirmation from that convoy).

Additionally, the convoy model provides an excellent framework for developing interventions for aging families because of its recognition of personal and situational characteristics. A study by Webster and Antonucci (2019) adapted the convoy model in an attempt to promote successful aging and social engagement among low‐income residents of senior housing by intervening to promote better interpersonal relationships. Initial findings indicate the importance of designing interventions that are sensitive to the population's specific situational and contextual factors, in this case low‐income older adults. Further development of interventions to promote healthy aging by leveraging older adults' convoys in situational and cultural contexts would be a productive direction of further inquiry. Building on the aforementioned cross‐national research (Ajrouch et al., 2017; Antonucci et al., 2001), researchers could seek to develop interventions for older families in a specific context. For instance, perhaps interventions for widows in France or Germany might warrant focusing on increasing availability of social support for older widows, whereas in Japan or the United States the needed intervention may not target the availability but rather the quality or function of support in widowhood. Convoys could be used to design interventions to address improving health behaviors or advancing sustainable development goals.

A primary topic of study that can benefit from using the convoy model to frame intervention research is informal caregiving in later life. Promoting a better and more supportive social convoy would not only reduce the burden for family caregivers but also improve communication and involvement of the broader support network, resulting in better outcomes for the elder‐care recipient at the center of the convoy, families, and society more generally. In recent years, interventions have been developed to test programs seeking to improve caregivers' social support (e.g., Dam, de Vugt, Klinkenberg, Verhey, & van Boxtel, 2016). Other researchers have used a convoy approach to address specific caregiving circumstances, such as end‐of‐life care (Albright et al., 2016) or caregiving in blended families (Sherman et al., 2013). Albright et al. (2016) found that the size of family convoys decreases for caregivers during hospice, suggesting the need for intervention to foster better convoy support during this time. Sherman et al. (2013) demonstrated both positive and negative attributes in their research on dementia caregiving in late‐life remarriages in which negativity and tension were experienced between spousal caregivers and stepchildren in particular. These represent examples of how the convoy model can be adapted as a framework for prevention or intervention work for aging families. Furthermore, we note that there is a need for culturally appropriate interventions. Given cultural differences in values related to elder‐care practices (Knight & Sayegh, 2010), interventions should recognize and prioritize the distinct features and needs of aging families in diverse cultural contexts. Future directions for caregiving interventions include exploring methods to intervene to foster more supportive convoy structures in later life, especially as the ability to reciprocate support dwindles with older adults' declining cognitive or physical health.

In terms of designing an intervention, the convoy model promotes an approach that examines social networks and support from a broad and reciprocal perspective. Interventions based on an individual convoy or convoys of multiple individuals in a family could be designed to build on resources of the older family member and to identify gaps to be addressed. For instance, given the likelihood of losing same‐aged peer convoy members as they age (e.g., death of spouse, siblings), perhaps intervention models could be designed to plan for this eventuality and address the “replacement” of lost convoy members with younger family members. Future research could explore such questions across cultural contexts and potentially gain new insights as to how different cultural groups successfully adapt family convoys to address late‐life losses. Furthermore, by identifying mutually supportive relationships, the convoy itself, as opposed to the individual, could serve as a unit of intervention. We can envision designing a program that includes the entire family convoy of the aging individual to intervene to prevent or address concerns such as loneliness or safe aging‐in‐place. By conducting research across cultural contexts, researchers may determine distinct problems to address and resources available.

The convoy model provides the flexibility to guide such research so as to identify and meet the needs of older people and their families by recognizing situational context as key to understanding the convoy and family functioning. For instance, imagine an intervention that takes a convoy perspective to promote support of elders within a tribal Native American community; it would be essential that researchers first possess an awareness and understanding of cultural values and practices as well as the role of fictive kin, tribal elders, historical events, and traumas before developing such an intervention. The convoy model has just begun to be used as a framework to inform prevention and intervention studies. It shows great promise as an adept framework for future inquiry as a means for promoting better social support and interactions among aging families in particular.

Conclusion

The convoy model presents a useful framework to advocate for a better quality of life for older people and their families. Family gerontology may benefit from the convoy model because it is clear that family structure evolves as societies change, yet the critical role of close relations remains stable (Antonucci et al., 2019). As demographic trends foreshadow a future of longer, healthier life expectancies and fewer children, it is likely that older adults will increasingly have active roles in intergenerational family units for longer periods of time (Carr & Utz, 2020). As we have outlined, the convoy model provides a useful heuristic for extending our view of changing families and evolving roles between family members, including the presence of older adults. The convoy model is an apt theoretical framework for use across the life span and over the life course, but it is especially valuable in highlighting the central role of older adults in the family. We have highlighted the ways in which the convoy model identifies key issues for understanding the role of older adults within families. The convoy model is particularly useful in that it can continually be adapted to address new questions as they arise and as new methods are developed. As the functions and needs of families shift, meaningful concepts and innovative methods are needed to capture and understand family functioning in later life. In this article we have highlighted several such illustrative methods and assert that the convoy model provides an ideal, flexible framework for researchers to continue to innovate as they study aging families and their convoys.

author note

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG045423, R01 AG057510, and P30 AG059300). We would like to thank the members of the Life Course Development program at ISR for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Moreover, we would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and guest editors Amy Rauer, Áine Humble, and Elise Radina for their insightful suggestions during the revision process.

references

- Ajrouch, K. J. (2005). Arab‐American immigrant elders' views about social support. Ageing & Society, 25, 655–673. 10.1017/S0144686X04002934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch, K. J. , Antonucci, T. C. , & Janevic, M. R. (2001). Social networks among Blacks and Whites: The interaction between race and age. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56, S112–S118. 10.1093/geronb/56.2.S112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch, K. J. , Antonucci, T. C. , & Webster, N. J. (2016). Volunteerism: Social network dynamics and education. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 309–319. 10.1093/geronb/gbu166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch, K. J. , Blandon, A. Y. , & Antonucci, T. C. (2005). Social networks among men and women: The effects of age and socioeconomic status. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 60, S311–S317. 10.1093/geronb/60.6.S311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch, K. J. , Fuller, H. R. , Akiyama, H. , & Antonucci, T. C. (2017). Convoys of social relations in cross‐national context. Gerontologist, 58, 488–499. 10.1093/geront/gnw204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright, D. L. , Washington, K. , Parker‐Oliver, D. , Lewis, A. , Kruse, R. L. , & Demiris, G. (2016). The social convoy for family caregivers over the course of hospice. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51, 213–219. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K. R. , Blieszner, R. , & Roberto, K. A. (2011). Perspectives on extended family and fictive kin in the later years: Strategies and meanings of kin reinterpretation. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 1156–1177. 10.1177/0192513X11404335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. (1985). Social support: Theoretical advances, recent findings and pressing issues In Sarason I. G. & Sarason B. R. (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research and applications (pp. 21–37). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 10.1007/978-94-009-5115-0_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. (1986). Measuring social support networks: Hierarchical mapping technique. Generations, 10, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control In Birren J. E. (Ed.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Ajrouch, K. J. , & Abdulrahim, S. (2014). Social relations in Lebanon: Convoys across the life course. Gerontologist, 55, 825–835. 10.1093/geront/gnt209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Ajrouch, K. J. , & Birditt, K. S. (2013). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist, 54, 82–92. 10.1093/geront/gnt118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Ajrouch, K. J. , & Manalel, J. A. (2017). Social relations and technology: Continuity, context, and change. Innovation in Aging, 1(3), 1–9. 10.1093/geroni/igx029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Ajrouch, K. J. , & Webster, N. J. (2019). Convoys of social relations: Cohort similarities and differences over 25 years. Psychology and Aging, 34, 1158–1169. 10.1037/pag0000375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Birditt, K. S. , Sherman, C. W. , & Trinh, S. (2011). Stability and change in the intergenerational family: A convoy approach. Ageing & Society, 31, 1084–1106. 10.1017/S0144686X1000098X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Fiori, K. L. , Birditt, K. , & Jackey, L. M. (2010). Convoys of social relations: Integrating life‐span and life‐course perspectives In Freund A. F., Lamb M. L., & Lerner R. M. (Eds.), Handbook of lifespan development (pp. 434–473). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , & Jackson, J. S. (1990). The role of reciprocity in social support In Sarason B. R., Sarason I. G., & Pierce G. R. (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 173–198). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , Lansford, J. E. , Schaberg, L. , Smith, J. , Baltes, M. , Akiyama, H. , … Dartigues, J. F. (2001). Widowhood and illness: A comparison of social network characteristics in France, Germany, Japan, and the United States. Psychology and Aging, 16, 655–665. 10.1037/0882-7974.16.4.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. , & Wong, K. M. (2010). Public health and the aging family. Public Health Reviews, 32, 512–531. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life‐span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology , 23, 611–626. 10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P. B. , Lindenberger, U. , & Staudinger, U. M. (2006). Life span theory in developmental psychology In Lerner R. M. & Damon W. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 569–664). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa Neves B., & Casimiro C. (Eds.). (2018). Connecting families? Information & communication technologies, generations, and the life course. Chicago, IL: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. L. , & Allen, K. R. (2009). The life course perspective applied to families over time In Boss P. G., Doherty W. J., LaRossa R., Schumm W. R., & Steinmetz S. K. (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 469–504). Boston, MA: Springer; 10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. , Giarrusso, R. , Mabry, J. B. , & Silverstein, M. D. (2002). Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: Complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 568–576. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00568.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. L. , & Roberts, R. E. (1991). Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: An example of formal theory construction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 856–870. 10.2307/352993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S. , Antonucci, T. C. , & Tighe, L. (2012). Enacted support during stressful life events in middle and older adulthood: An examination of the interpersonal context. Psychology and Aging, 27, 728–741. 10.1037/a0026967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S. , Jackey, L. M. , & Antonucci, T. C. (2009). Longitudinal patterns of negative relationship quality across adulthood. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 64, 55–64. 10.1093/geronb/gbn031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]