Abstract

Greater Poland is a region with a high risk of cancer. In terms of age-standardised incidence rate, it is ranked 2nd for men and 3rd for women out of Poland’s 16 provinces. Incidence structure in the region of Greater Poland is similar to that in other West European countries. The most common cancers in men are lung, prostate and colorectal, in women: breast, colorectal and lung. In 2016, nearly every third cancer-related death in the region was caused by lung cancer. In women, it was cause no. one. The incidence of chronic diseases, including cancer, is expected to further grow in view of the global ageing of the population. This means that malignancies will remain to be a major challenge for public health care.in the Greater Poland region.

Keywords: Cancer incidence trends, Cancer epidemiology

1. Introduction

Greater Poland is one of Poland’s largest provinces both in terms of area (second largest with 29,825 sq. km) and population (third most populous with population of 3,477,755). The population of the province is feminised with 106 women per 100 men. It consists of 31 country districts and 4 townships districts, divided into 226 communes (including 118 rural communes, 89 rural-municipal communes and 19 municipalities). Cancer represents the second most common death cause in the Greater Poland region following cardiovascular diseases.26 Considering the population ageing forecasts for the region, that health-related and economic issue will grow even bigger. Greater Poland is a region with a high risk of cancer. In 2016, both its male and female populations were ranked second in Poland in terms of age standardised incidence. In terms of mortality, Greater Poland was ranked third for male population, and fifth for female population. The National Cancer Control Programme implemented by a legislative act in 2005 was meant to reduce cancer incidence and mortality as well as improve treatment efficacy within ten years. The Greater Poland region has started implementing both the national programmes (such as Population-Based Programme for Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical and Colorectal Cancers, Population-Based Programme for Early Detection of Breast Cancer and, additionally, from 2019 - the National Programme for Prevention of Skin Cancers) and provincial programmes (Programme for Prevention of Head & Neck Cancers or Programme for Early Detection of Lung Cancer). In 2020, the Greater Poland Cancer Centre will start carrying out its self-designed programme called Prevention of Severe Pneumonia and Post-Influenza Complications in Cancer Patients. Cancer registration in Poland is based on a legal act and conducted by the National Cancer Registry and its 16 regional offices. The Greater Poland Cancer Registry is the only active population-based registry that collects detailed data on cancer incidence and mortality in the Greater Poland region. The Registry collects data from a specific area (using the ICD-10 and O3 classification for topography and morphology), for a population of strictly defined structure and size. For years, the Greater Poland Cancer Registry has been marked with a high level of completeness and quality of data collected. For the 2016 data, a 100% completeness was again achieved (Poland’s average 98%) and quality (i.e. proportion of histology confirmations) of 92% (Poland’s average 90%).24

2. Aim

To assess trends in cancer incidence in the Greater Poland region in 1999 and 2016 and compare them to other European countries. Analysis of age standardised incidence rates in Greater Poland in 1999-2016 and comparison to Europe’s average.

3. Material and method

The article analyses data on the incidence of cancers in the province of Greater Poland by gender, district, age and site (according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision) and compares data for Poland and Europe. The article was based on data from the National Cancer Registry as collected from Cancer Notification Forms. Compared 5 the most common cancers (by sex) in Greater Poland Region with Poland and Europe. Incidence comparisons to Europe were based on data from the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer, and Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), while those regarding five-year survival rates were based on CONCORD-3 studies. The study employed several basic statistical indicators, such as absolute numbers, proportions, and crude age-standardised rates. The article uses a direct result standardisation method with ‘standard world population’ taken as a standard population.

4. Results

In 2016, 15,867 new cancer cases were reported to the Greater Poland Cancer Registry (7,925 men and 7,942 women). Compared to 1999, the number of new cases rose by 54% (5,556) – for detailed data for 1999 and 2016 seen Table 1.

Table 1.

Cancer incidence, Wielkopolska region, 1999-2016.1

| year | Male |

Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolute number | crude rate | ASRw | absolute number | crude rate | ASRw | |

| 1999 | 5 128 | 314,2 | 272,8 | 5 183 | 302,3 | 209,7 |

| 2000 | 5 264 | 319,4 | 271,7 | 5 387 | 310,2 | 214 |

| 2001 | 5 367 | 324,4 | 274,4 | 5 559 | 319,0 | 215,3 |

| 2002 | 5 584 | 332,3 | 275,4 | 5 616 | 317,8 | 211,5 |

| 2003 | 5 749 | 345,8 | 281,1 | 5 722 | 322,9 | 211,5 |

| 2004 | 5 908 | 351,6 | 282,2 | 5 770 | 327,3 | 213,2 |

| 2005 | 6 340 | 359,8 | 282,5 | 6 282 | 341,3 | 219,9 |

| 2006 | 6 513 | 374,2 | 298,2 | 6 178 | 337,8 | 215,3 |

| 2007 | 6 749 | 385,5 | 289,3 | 6 746 | 369,0 | 230,1 |

| 2008 | 7 086 | 404,7 | 298,9 | 6 714 | 360,8 | 224,6 |

| 2009 | 6 964 | 398,5 | 290,5 | 6 749 | 366,5 | 227,3 |

| 2010 | 6 722 | 401,5 | 287,2 | 6 859 | 388,1 | 235,3 |

| 2011 | 6 850 | 408,1 | 285,2 | 6 966 | 393,1 | 235,2 |

| 2012 | 7 140 | 424,4 | 290,3 | 7 122 | 400,9 | 234,2 |

| 2013 | 7 534 | 447,2 | 299,1 | 7 515 | 422,5 | 248,3 |

| 2014 | 7 291 | 432,0 | 283,3 | 7 530 | 422,6 | 244,9 |

| 2015 | 7 921 | 468,6 | 298,5 | 8 060 | 451,9 | 253,2 |

| 2016 | 7 925 | 468,3 | 294,0 | 7 942 | 444,8 | 250,2 |

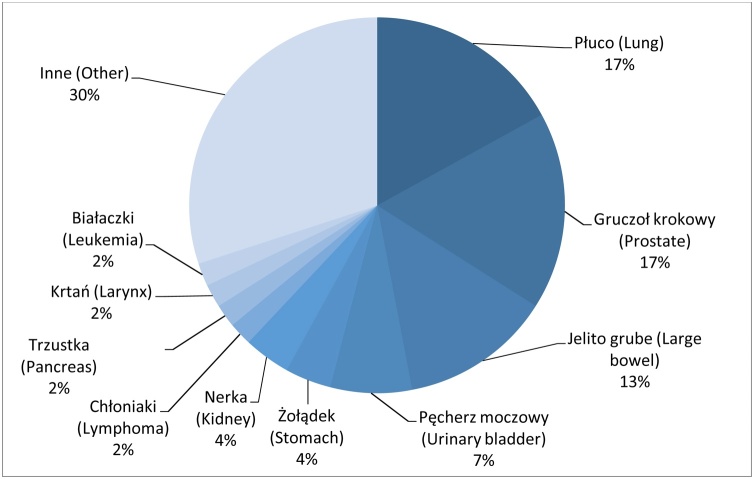

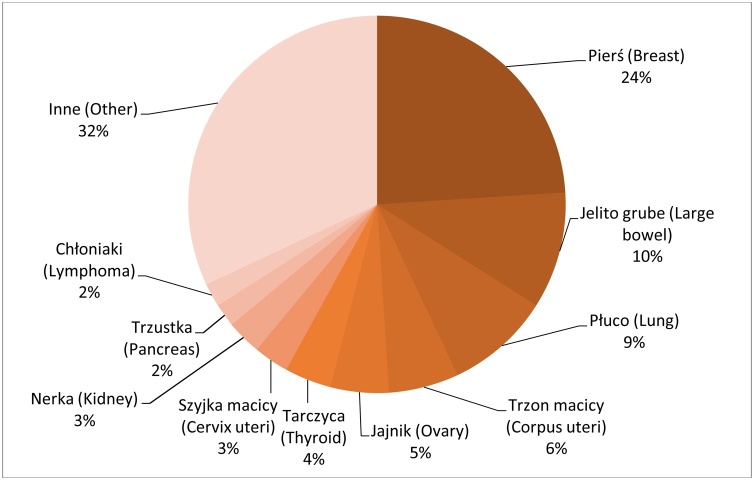

In 2016, the most common cancers in men were lung, prostate, colorectal cancers, urinary bladder and stomach. In women, the most prevalent cancer types are breast, colorectal, lung cancers, corpus uteri and ovary.1,2 In Poland in 2016, the most common cancers in men were prostate, lung, colorectal cancers, urinary bladder and stomach. In women, the most prevalent cancer types are breast, lung, colorectal cancers, corpus uteri and ovary.1 In Europe, the most common cancers in men were prostate, lung, colorectal cancers, urinary bladder and stomach. In women, the most prevalent cancer types are breast, colorectal, lung cancers, corpus uteri and melanoma of skin (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).27

Fig. 1.

Cancer incidence distribution in men, Wielkopolska region, 2016.1

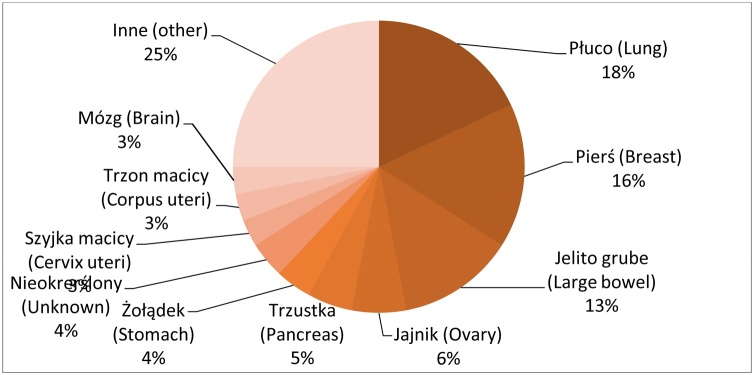

Fig. 2.

Cancer incidence distribution in women, Wielkopolska region, 2016.1

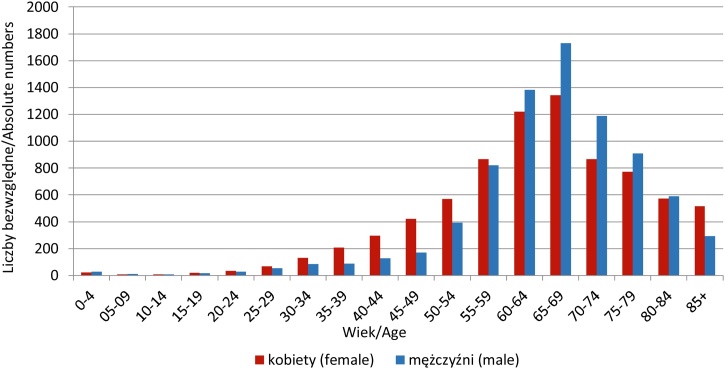

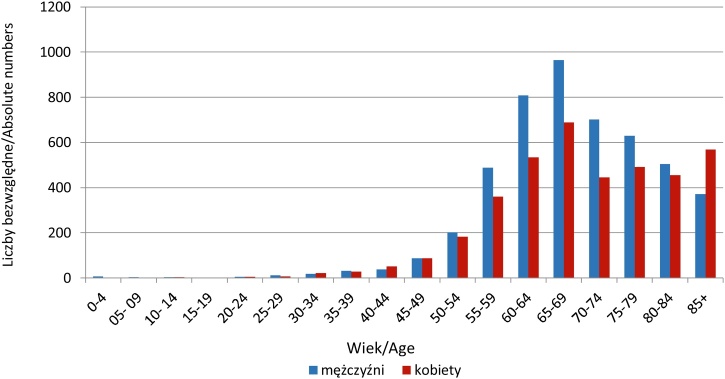

The youngest patient was 2 days old, the oldest was 102 years old (88% of diagnosed patients were aged 50+, versus 82% in 1999). Incidence distribution by gender and age groups in 2016 is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Number of cancer cases in the region of Wielkopolska by age groups, 2016.1

In 2016, 459 cancer cases were detected in the Greater Poland region through screening tests (compared to 29 in 2005 when the National Cancer Control Programme was launched). Of them, 421 were breast cancers, 9 cervical cancers, and 4 colorectal cancers. 121 cancer cases were diagnosed in children aged 0–19 (the incidence crude rate in children is 16/100,000 of both sexes). According to the Central Statistical Office data, 8,813 cancer-related deaths were registered in the province of Greater Poland in 2016 (4,879 men and 3,934 women) representing an increase by nearly 19% as compared to 1999 (i.e. by 1,430 cases – Table 2). Data from 1999 and 2016 are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cancer-related deaths in the Wielkopolska region in 1999-2016.1

| year | Male |

Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolute number | crude rate | ASRw | absolute number | crude rate | ASRw | |

| 1999 | 4 149 | 254,7 | 219,5 | 3 234 | 188,1 | 117,6 |

| 2000 | 4 108 | 251,9 | 212,5 | 3 321 | 192,9 | 117,8 |

| 2001 | 4 178 | 255,8 | 211,6 | 3 408 | 197,6 | 119,0 |

| 2002 | 4 193 | 258 | 210,5 | 3 391 | 196,8 | 116,9 |

| 2003 | 4 266 | 262,3 | 209,6 | 3 329 | 193,0 | 111,7 |

| 2004 | 4 550 | 279,3 | 220,8 | 3 407 | 197,2 | 112,8 |

| 2005 | 4 345 | 266,2 | 206,4 | 3 540 | 204,4 | 114,5 |

| 2006 | 4 572 | 279,6 | 217,1 | 3 679 | 212,0 | 123,7 |

| 2007 | 4 570 | 279 | 205,5 | 3 710 | 213,3 | 116,7 |

| 2008 | 4 606 | 280,4 | 201,2 | 3 573 | 204,8 | 107,9 |

| 2009 | 4 545 | 275,7 | 194,8 | 3 713 | 212,1 | 111,5 |

| 2010 | 4 603 | 277,5 | 192,1 | 3 615 | 205,3 | 105,3 |

| 2011 | 4 545 | 270,8 | 185,0 | 3 636 | 205,2 | 104,8 |

| 2012 | 4 498 | 267,4 | 177,4 | 3 66 | 206,4 | 103,3 |

| 2013 | 4 432 | 163,1 | 169,7 | 3 547 | 199,4 | 100,4 |

| 2014 | 4 577 | 271,2 | 171,7 | 3 697 | 207,5 | 102,1 |

| 2015 | 4 760 | 281,6 | 174,7 | 3 757 | 210,6 | 99,6 |

| 2016 | 4 879 | 288,3 | 173,9 | 3 934 | 220,3 | 102,4 |

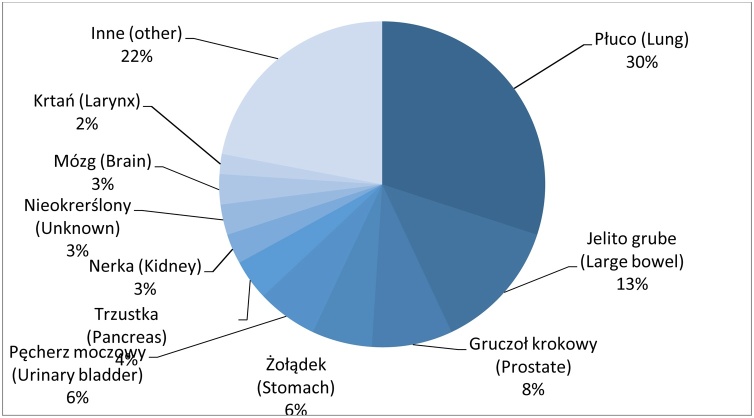

In 2016, the most common cause of cancer-related death in men was cancer of the lung followed by colorectum and prostate (Fig. 4), in women: cancer of the lung followed by breast and colorectum (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Death distribution in men, Wielkopolska region, 2016.

Fig. 5.

Death distribution in women, Wielkopolska region, 2016.

Approximately 95% deaths were recorded for patients aged 50+ (as compared to 90% in 1999). Absolute number of cancer-related deaths in the Greater Poland region by age groups is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Number of cancer-related deaths in the region of Wielkopolska by age groups, 2016.

5. Discussion

Contrary to a common belief, only a small proportion of malignancies develop due to inherited predispositions. A vast majority results from a long-lasting accumulation of DNA damage. There is clear evidence that cancer can be prevented, and from 80% to 90% of cancers occurring in western populations can be attributed to environmental factors, such as food habits and social or cultural behaviour.2 Among factors increasing the risk of cancer, 30% are related to smoking, 30% to improper diet, 15% to inherited factors, 5% to infections, 5% to job-related factors, 5% to obesity and lack of physical activity, 3% to abuse of alcohol, 2% to UV radiation, 2% to drugs, 2% to environment pollution and 1% to other factors.3 Not only nations, but even populations of particular regions differ in their lifestyles (including diets, smoking, physical activity, etc.), which has a strong impact on the incidence and course of diseases and, consequently, also life expectancy. The 2015 European health report by WHO indicated smoking, alcohol, overweight and obesity as the main public health issues in the WHO Europe region, underlining their importance as main risk factors for premature mortality due to the most common non-communicable diseases (such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases).4 In turn, analyses conducted under the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study show that in Polish (as in the other Central European natons) smoking, wrong diet and high blood pressure are the factors responsible for the loss of the highest number of disability adjusted life-years (DALY).5 In 2017, the behavioural, i.e. modifiable, risk factors alone were caused the loss of 37% of disability adjusted life-years, of which 14% is directly attributable to diet (overweight and obesity excluded) and 17% to smoking. The proportion of regular smokers in Poland is estimated to be slightly above EU average. The latest studies by the National Institute of Public Health - National Institute of Hygiene (NIZP-PZH) and Central Statistical Office (GUS) indicate a decrease in the proportion of male Poles regularly smoking tobacco from 41% in 1996 to 28% in 2018; in the case of Polish females, the decrease is less pronounced: from 19% to 15%.6 The NIZP-PZH and GUS studies do not take into account regional analyses, the only available data20,21 reflect the decrease in the proportion of male smoker population of the Greater Poland region from 43.2% in 2006 to 36.0% in 2014,. In the case of female population, the decrease is smaller: from 27% to 22%, respectively. Analysis of smoking prevalence by place of residence (urban/rural) does not show much difference for men, for women, however, region from 43.2% in 2006 to 36.0% in 2014,. In the case of female population, the decrease is smaller: from 27% to 22%, respectively. Analysis of smoking prevalence by place of residence (urban/rural) does not show much difference for men, for women, however.7, 8, 9 Consumption of alcohol in Poland has for many years remained at a level similar to Europe’s average. According to the estimates of the WHO Global Health Observatory, in 2015-2017 it was 10.5 L/person for the age group of 15+ and was lower by 0.2 litre than in the period of 2009-2011.10 There are no regional analyses regarding the use of alcohol; however, data from the National Agency for Alcohol Related Problems Resolution.25 indicate that the amount of alcohol sold in the Greater Poland region in 2018 accounted for 9% of the total alcohol sales in Poland. With the disability adjusted life-years (DALY) rate of 14% for men, Poland is ranked at the 10th position among EU countries (together with Lithuania). The DAILY rate of 2% for women is one of the lowest in EU, with only seven countries scoring better.11 The global burden of disease studies confirm an adverse impact of overweight on health identifying it as the fourth most significant risk factor in terms of the total burden of disease for Poland’s population, and the fifth most significant factor for all the Central and Western European countries.5 In Poland, it causes the loss of 11% disability adjusted life-years (DALY) for men and 12% for women. According to WHO estimates for 2016, the proportion of men with excessive body mass (BMI 25+) in the UE is over 60% (69% for Poland), and over 50% (57% for women). For Greater Poland, the results are slightly better. According to data for 2014,21 the proportion of Greater Poland male population with BMI 25+ is 66%, while for female population it is 41%. Improper diet, in particular low intake of vegetables and fruit, may lead to obesity, hipercholesterolemia and shortage of vitamins, contributing, among others, to cancer. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017, insufficient consumption of fruit in Poland leads to the loss of 4% of disability adjusted life-years, while the low consumption of vegetables, to 3%.5 According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Poland has for many years been among the countries with the lowest consumption of fruit in Europe. In 2013, it was 60.2 kg/person/year versus the EU’s average of 103.7 kg/person/year. Consumption of vegetables (excluding potatoes) in Poland is close to EU’s average.12 The consumption of fruit and vegetables is related to consumers’ financial position.13 Low level of physical activity in Poland is responsible for the loss of 2% of disability adjusted life-years.5 According to WHO recommendations, individuals aged 18-64 should do physical activity of moderate intensity every week for at least 150 min. or physical activity of high intensity for at least 75 min.14 However, the results of Eurobarometre survey of 2017, indicate that only 7% of EU citizens aged above 15 years regularly (5x a week or more) do sports or physical exercise, while 14% engage in other recreational forms of activity (cycling, dancing, survey of 2017, indicate that only 7% of EU citizens aged above 15 years regularly (5x a week or more) do sports or physical exercise, while 14% engage in other recreational forms of activity (cycling, dancing, gardening etc.).15 Differences between particular countries are substantial but, regrettably, in this regard, too, Poland’s performance is poor with 5% of population taking regular physical exercise, and 9% engaging in other forms of activity. As many as 56% of Poles do not do any sports at all (11% in Greater Poland).21 The level of physical activity is closely related to education: the proportion of population who do no physical exercise is 81% for individuals with secondary education or lower and 36% for those with higher education. Over the 17 years, the number of new cancer cases in Poland rose by 47% (by 54% in Greater Poland – Table 3). The National Cancer Registry data show that a high discrepancy in this respect across the 16 provinces: from 252% growth in the Lublin province to 17% growth in the Podlasie province (Table 3).

Table 3.

Increase in the number of cancer cases in Poland’s 16 provinces, 2016 vs. 1999.1

| provinces | cancer incidence, 1999 year | cancer incidence 2016 year | 2016 vs 1999 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Podlaskie | 3 639 | 4 251 | 117% |

| Opolskie | 3 310 | 4 042 | 122% |

| Śląskie | 15 733 | 19 556 | 124% |

| Świętokrzyskie | 4 958 | 6 182 | 125% |

| Małopolskie | 10 520 | 13 249 | 126% |

| Dolnośląskie | 10 556 | 13 413 | 127% |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 4 936 | 7 088 | 144% |

| Mazowieckie | 13 536 | 19 541 | 144% |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 6 608 | 9 855 | 149% |

| Pomorskie | 7 483 | 11 300 | 151% |

| Wielkopolskie | 10 316 | 15 867 | 154% |

| Podkarpackie | 5 275 | 8 656 | 164% |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 3 637 | 6 260 | 172% |

| Lubelskie | 4 826 | 9 186 | 190% |

| Łódzkie | 5 289 | 11 653 | 220% |

| Lubuskie | 1 149 | 4 041 | 352% |

| Total | 111 771 | 164 140 | 147% |

This high discrepancy requires further studies to determine whether it only results from the differences in the completeness of cancer registration and level of diagnosis or from big differences in the awareness and related health behaviour. For example, the preventive mammography coverage for the female population of the Greater Poland region as of 01/01/2016 was 52% (Poland's average: 44%, EU’s average 49%).22,23 For cytology the coverage for the female population of the Greater Poland region as of 01/02/2016 was 16% (Poland's average: 21%, EU’s average 46%).22,23 In 2011, the head of the Greater Poland Cancer Centre together with the head of Head & Neck Surgery and ENT Oncology Clinic began efforts aimed to extend the National Cancer Control Programme to include the National Programme for Prevention and Early Detection of Head and Neck Cancers module. Since June 2014, the GPCC has coordinated the implementation of this innovative (for both Polish and European standards) programme. In 2014-2016, 6,000 male individuals from the Greater Poland region were examined, 405 were referred for further diagnosis and 47 were diagnosed with cancer. Based on Greater Poland’s experience gathered through the pilot prevention screening, the nationwide programme was launched in July 2017.24 In terms of age-standardised incidence rates, Poland is ranked 29th out of 39 European countries (ASRw = 254/100,000; max. 374/100 000 in Ireland; min. 174/100,000 in Albania).16 In terms of age-standardised mortality rates, Poland is ranked 6th out of 39 European countries (ASRw = 137/100,000; max. 156/100 000 in Hungary; min. 84/100,000 in Finland).16 The average incidence rate and high mortality rate are associated with the efficacy of treatment. The CONCORD-3 report on five-year survival rates in cancer patients in particular countries worldwide (covering the period from 2004 to 2014) demonstrates that, despite the progress Poland made in cancer treatment, the effectiveness is still unsatisfactory (compared to other European countries). A clear progress has been made in prostate cancer where the five-year survival rate rose in the reference period by 10 percent points (from 68.8% to 78.1%). A significant progress (also reaching 10 percent points) was also achieved in the treatment of haemato-oncological diseases (leukaemia, lymphomas and plasma myelomas). In the case of paediatric lymphomas, the five-year survival rate increased from 81.7% to 92.6%, in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia from 79.6% to 86.9%. In adults, the effectiveness of treatment of plasma myeloma rose from 18.9% to 27.3%. For breast cancer, it rose from 71.3% to 76.5%; for colon cancer from 45.3% to 52.9%, and for rectal cancer from 42.5% to 48.4%. In many European countries, the effectiveness of cancer treatment is better, e.g. breast cancer patients’ five-year survival rate in Norway is 87.7%, in Sweden 88.8%.17 Ageing of society combined with an irrational aversion to preventive medicine will constitute an important factor of cancer incidence and mortality in the second half of the 21 st century. According to the National Cancer Registry forecasts, the number of new cancer cases in Poland will rise to over 176,000 by 2025 (i.e. by 7%).18 In turn, GLOBOCAN forecasts a growth to nearly 204,000, i.e. by 24%. A similar increase of 27% by 2025 is predicted by the Greater Poland Cancer Registry (the number of new cancer cases in the Greater Poland region expected to exceed 20,150, with 9,000 deaths – Table 4).

Table 4.

Predicted global increase in the number of cancer cases and deaths in the Wielkopolska region.19

| year | Male incidence | Female incidence | Male mortality | Female mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 8 270 | 8 216 | 4 750 | 3 829 |

| 2018 | 8 482 | 8 424 | 4 783 | 3 859 |

| 2019 | 8 699 | 8 636 | 4 816 | 3 889 |

| 2020 | 8 922 | 8 854 | 4 849 | 3 920 |

| 2021 | 9 151 | 9 077 | 4 883 | 3 951 |

| 2022 | 9 385 | 9 306 | 4 917 | 3 982 |

| 2023 | 9 626 | 9 541 | 4 951 | 4 013 |

| 2024 | 9 872 | 9 781 | 4 985 | 4 045 |

| 2025 | 10 125 | 10 028 | 5 020 | 4 077 |

6. Conclusion

According to predictions, cancer incidence in Poland (and Greater Poland) will rise, among others, because of the global ageing of the population (and accumulation of carcinogenic factors). Effective cancer control requires a strategy to guide the patient from educative actions through (prevention), diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, reconnaissance up to the return to professional and social life. Owing to disease prevention, direct (related to therapy) and indirect (e.g. arising from patients’ and their family members’ absence at work) costs can be reduced. Great Poles must be persuaded to change their lifestyles. However, without effective organisational solutions, the system will not manage to deal with the lifestyle disease epidemic; therefore, health expenditure needs to be increased (currently, mean amount of spending per capita in the EU is EUR 2,892 versus EUR 1,341 in Poland!). Data collected by the Greater Poland Cancer Registry allow to develop a health care strategy for the Greater Poland Province and define future demand for beds, medical staff and necessary equipment in oncology care. The most significant task of the Registry is to gather information for use in scientific research, publications, patient follow-up and cancer control programmes.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Contributor Information

Agnieszka Dyzmann-Sroka, Email: agnieszka.dyzmann-sroka@wco.pl.

Julian Malicki, Email: julian.malicki@wco.pl.

Agnieszka Jędrzejczak, Email: agnieszka.jedrzejczak@wco.pl.

References

- 1.Wojciechowska U., Didkowska J. Zachorowania i zgony na nowotwory złośliwe w Polsce. Krajowy Rejestr Nowotworów, Centrum Onkologii - Instytut im. Marii Skłodowskiej - Curie. Dostępne na stronie http://onkologia.org.pl/raporty/ dostęp z dnia 01/06/2019.

- 2.Zatoński W. Europejski Kodeks Walki z Rakiem, 2003 r., Centrum Onkologii-Instytut im. M. Skłodowskiej-Curie, Warszawa 2009.

- 3.Beliveau R., Gingras D. Delta; 2007. Dieta w walce z rakiem. Profilaktyka i wspomaganie terapii przez odżywianie. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO, Regional Office for Europe, the European health report 2015, dostępne 9.11.2018 r.).

- 5.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation GBD Compare https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/(dostępne: 12.11.2018).

- 6.Wojtyniak B., Goryński P. NIZP-PZH; Warszawa: 2018. Sytuacja zdrowotna ludności Polski i jej uwarunkowania. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GUS . 1998. Stan Zdrowia Ludności Polski w 1996 r. Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- 8.GUS . 2011. Stan Zdrowia Ludności Polski w 2009 r. i. Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- 9.GUS . 2016. Stan Zdrowia Ludności Polski w 2014 r. Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Health Obsevatory data repository http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A1029?lang=eng, dostęp 22.11.2018r.).

- 11.Suplement to: GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: systematic analyzes for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. http://dx.doi.ogr/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31310-2 publish online Aug 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ Dane: FAOSTAT Data Base, 2015.

- 13.GUS . 2018. Budżety gospodarstw domowych w 2017 r. Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . 2010. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.TNS Opinion & social dla Generalnej Dyrekcji Komisji Europejskiej ds. Edukacji, Młodzieży, Sportu i Kultury, Special Eurobarometer 472, Sport and Physical Activity 2017.

- 16.WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Global Cancer Observatory. Dostępne na stronie: https://gco.iarc.fr/ dostęp z dnia 3.09.2019 r.

- 17.Allemani C., Matsuda T, et al. Global surveillence of trends in cancer survival 2000-2014 (CONCORD-3): analysis of indyvidual records for 37 515 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 polpulation-based registries in 71 countries, published online Jan. 30, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Didkowska J., Wojciechowska U., Zatoński W. Centrum Onkologii-Instytut; Warszawa: 2009. Prognozy zachorowalności i umieralności na nowotwory złośliwe w Polsce do 2025 r. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyzmann-Sroka A., Trojanowski M. The M. Sklodowska-Curie memorial, Greater Poland Cancer Center, Bulletin No 15; Poznań: 2018. Cancer in the region of Greater Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badanie “Wiedza o nowotworach i profilaktyce zrealizowane w ramach Narodowego Programu Zwalczania chorób nowotworowych na zlecenie COI w Warszawie, przeprowadzone w 2006 roku przez PBS-DGA.

- 21.Badanie “Wiedza o nowotworach i profilaktyce zrealizowane w ramach Narodowego Programu Zwalczania chorób nowotworowych na zlecenie COI w Warszawie, przeprowadzone w 2014 roku przez PBS-DGA.

- 22.Dane o realizacji programu profilaktyki raka piersi i raka szyjki macicy dostępne na stronie Ministerstwa Zdrowia: www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/profialktyka-onkologiczna, data wejścia: 2020-03-02.

- 23.Cancer screening in the European Union 2017 . International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon France: 2017. Report on the implamentation of the Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening. January. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyzmann-Sroka A., Trojanowski M., Grochowicz J. i wsp., Cancer in the region in Greater Poland, 2016. Greater Poland Cancer Center, Bulletin No. 15, Poznań 2018.

- 25.Profilaktyka i rozwiązywanie problemów alkoholowych w Polsce w samorządach gminnych w 2018 roku. PARPA,25.09.2019 r.

- 26.Statistical yearbook 2016. Wielkopolskie Voivodship. Statistical Office in Poznań.

- 27.GLOBOCAN 2018, International Agency for Research on Cancer, dostępne na stronie: www.gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis, data wejścia: 2020-03-10.