Key Points

Anti-CD45RC mAb inhibits aGVHD and induces tolerance to recipient alloantigens in rats, mice, and humans.

Anti-CD45RC mAb preserves immune responses against third-party alloantigens, graft-versus-tumor, and memory immune responses.

Abstract

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is a widely spread treatment of many hematological diseases, but its most important side effect is graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Despite the development of new therapies, acute GVHD (aGVHD) occurs in 30% to 50% of allogeneic BMT and is characterized by the generation of effector T (Teff) cells with production of inflammatory cytokines. We previously demonstrated that a short anti-CD45RC monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment in a heart allograft rat model transiently decreased CD45RChigh Teff cells and increased regulatory T cell (Treg) number and function allowing long-term donor-specific tolerance. Here, we demonstrated in rat and mouse allogeneic GVHD, as well as in xenogeneic GVHD mediated by human T cells in NSG mice, that both ex vivo depletion of CD45RChigh T cells and in vivo treatment with short-course anti-CD45RC mAbs inhibited aGVHD. In the rat model, we demonstrated that long surviving animals treated with anti-CD45RC mAbs were fully engrafted with donor cells and developed a donor-specific tolerance. Finally, we validated the rejection of a human tumor in NSG mice infused with human cells and treated with anti-CD45RC mAbs. The anti-human CD45RC mAbs showed a favorable safety profile because it did not abolish human memory antiviral immune responses, nor trigger cytokine release in in vitro assays. Altogether, our results show the potential of a prophylactic treatment with anti-human CD45RC mAbs in combination with rapamycin as a new therapy to treat aGVHD without abolishing the antitumor effect.

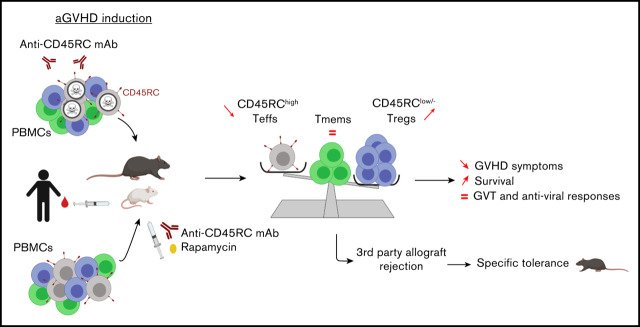

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Allogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantation (BMT) is the best treatment of BM failure syndromes, congenital immune deficiencies and for various hematologic malignancies. Unfortunately, acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD; aGVHD) is a frequent (30% to 50%) life-threatening complication of BMT.1 In aGVHD, donor T cells present in the BMT become activated against recipient antigens and attack recipients’ tissues through cell-mediated cytotoxicity and production of inflammatory cytokines.1

A variety of treatments are used either in prophylactic and/or curative protocols, but there is a clear need for new therapeutics because a high proportion of patients developing aGVHD are bad responders, thus leading to high morbidity and mortality rates. In addition, excessive immunosuppression aiming to control aGVHD frequently leads to severe infections.1,2 Another significant proportion of patients (≈40%) develops chronic GVHD with high morbidity and also mortality.1,2 Among the prophylactic standard of care treatments, steroids, immunosuppressors and polyclonal antithymocyte globulins (ATGs) are routinely used.2 If aGVHD occurs, a first line of standard-of-care treatments includes higher doses of steroids and immunosuppressors such as calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or rapamycin.2 For aGVHD patients unresponsive to steroids and immunosuppressors, there is no real standard of care and a variety of treatments are used including ATG, rapamycin, Jak inhibitors, anti-CD2, CD3, CD25, CD26, CD30, CD52, CCR5, and interleukin 6 (IL-6) antibody (Ab) treatments, as well as cell therapy with regulatory T cells (Tregs) or mesenchymal stem cells, with encouraging results in early clinical trials.1,2 However, none of these treatments has shown efficacy in large multicentric clinical trials.2 Another requirement is that aGVHD prophylactic or curative treatments should not ablate T cells present in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) preparation because donor T cells may be implicated in the graft-versus-leukemia/tumor (GVL/T) effect, as well as in immune recovery against infectious agents.

CD45RC is an isoform of CD45 that we showed to be expressed at least in both rats3-10 and humans11-14 at high levels in T cells (T CD45RChigh) precursors of Th1 as well as in terminally differentiated effector memory (TEMRA) cells that are responsible for acute solid organ rejection and aGVHD. Conversely, Th2 precursors as well as CD4+ and CD8+ Foxp3+ Treg that are able to inhibit acute solid organ rejection and aGVHD are all CD45RClow/- both in rats3-10 and humans.11-14 In a solid organ transplantation fully MHC-incompatible rat model, we showed that a short course of anti-CD45RC mAb treatment induced preferential depletion of CD45RChigh T cells leading to permanent allogeneic tolerance through the induction of activated donor-specific CD8+ and CD4+ Tregs.9 In anti-CD45RC–treated animals, memory and de novo immune responses were preserved.

In the present manuscript, we further explored the use of anti-CD45RC mAb treatment in aGVHD. We applied ex vivo or in vivo an anti-CD45RC prophylactic treatment of aGVHD in semi-allogeneic rat and mouse models of BMT, as well as in the model of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) transfer into NSG mice. We used 3 species-specific anti-CD45RC mAbs, including a new chimeric anti-human mAb called ABIS-45RC. Ex vivo depletion of donor CD45RChigh T cells prior to infusion into recipients prevented aGVHD in >90% of grafted animals. In vivo anti-CD45RC mAb treatment alone significantly prolonged survival synergistically with a suboptimal dose of rapamycin. Long-surviving animals showed complete donor chimerism, tolerance to recipient alloantigens, and preservation of immune responses against third-party alloantigens. Importantly, the graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect in immune-humanized NSG mice treated with the new chimeric anti-human CD45RC ABIS-45RC mAb was preserved. We also showed that ABIS-45RC induced apoptosis of human CD45RChigh T cells, only recognized immune cells in a variety of human tissues, and preserved in vitro antiviral immune responses without inducing cytokine release by human immune cells. Finally, in a preclinical validation of CD45RC as a therapeutic target, we analyzed its expression in BM and blood of BMT patients and showed that CD45RC expression in T cells was the same as in healthy individuals.

Altogether, we show the potential of anti-human CD45RC mAbs as a new therapy against aGVHD.

Materials and methods

Animals and models

Hemi-incompatible aGVHD rat model.

The rat GVHD model15 was used with some modifications. Briefly, 2 × 107 male Lewis (Lew) T cells or equivalent of FACSAria-sorted CD45RC− male Lew T cells were injected IV in 8- to 9-week-old F1 Lew/Brown Norway (BN) male rats treated at day −1 with whole-body sublethal irradiation of 4.5 Gy. T cells were obtained by negative selection after incubation with anti-CD161 (3.2.3), anti-CD45RA (OX33), and anti-CD11b/c (OX42) mAbs. Recipients of total T cells were treated with anti-CD45RC mAb (OX22) or isotype control mAb (3G8) starting at day 0 until day 30 at 1.5 mg/kg per injection intraperitoneally every 2.5 days, and rapamycin (Rapamune; Pfizer) 0.8 or 0.4 mg/kg every day from day 0 to day 10 orally. Injected rats were scored (weight loss, posture, activity, fur texture, skin integrity) (supplemental Table 1) every day and euthanized when score was over 10. Experimental procedures were specifically approved by the local ethic committee (no. APAFIS# 3143 for rat and 2525 for NSG mice).

Hemi-incompatible aGVHD mouse model.

Female C57BL/6J (B6, H-2b) and female (B6×C3H) F1 (H-2bxk) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (France) and used at 8 to 10 weeks of age. Ten- to 12-week-old recipient (B6×C3H) F1 female mice received a lethal 10 Gy irradiation (radiograph) followed by retro-orbital infusion of 107 BM cells and 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6 donors. BM and T-cell suspensions were prepared using leg bones and lymph nodes, respectively, as previously described.16,17 GVHD was evaluated 3 times per week as previously described in detail.16,17 Briefly, each of the 5 following parameters were scored 0 (if absent) or 1 if present: weight loss >10% of initial weight, hunching posture, skin lesion, dull fur, and diarrhea. Dead mice received a total score of 5. Anti-CD45RC mAb (DNL1-9 clone) and isotype control mAb (R35-95 clone) were purchased from BD Biosciences. Recipient mice were treated intraperitoneally every 2.5 days with 0.8 mg/kg of the antibodies . Experimental procedures were specifically approved by the local ethic committee (no. APAFIS#11511-2017092610086943).

aGVHD model in immune-humanized NSG mouse.

Recipient NSG mice (8- to 12-week old) treated 16 hours earlier with whole-body sublethal irradiation of 1.5 Gy were injected IV with 1.5 × 107 PBMCs or CD45RAlow/− PBMCs or ABIS-45RC preincubated PBMCs or equivalent of FACSAria-sorted CD45RClow/− or CD45RAlow/− PBMCs or ABIS-45RC preincubated PBMCs from healthy volunteer (HV) donors. PBMC-transplanted mice received a chimeric (mouse-human) anti-human CD45RC mAb (ABIS-45RC clone) every 2.5 days at 0.8 mg/kg per injection intraperitoneally starting from day 0 until day 20 with or without rapamycin orally (0.4 mg/kg per day for 10 days). Body weights were monitored every day for 100 days. Recipients were euthanized when percentage of weight loss was ≥20% of their initial weight. Groups of 5 to 10 animals were treated and matched in age, sex, and initial weight and randomly treated.

Histological analysis

Rats were euthanized at day 28 or after day 150 for long survivors to harvest small intestine. Organs were fixed in PFA 4% at least for a week. Slides were included in paraffin, sliced in 5-µm sections and colored with Hematoxylin Eosin Safran (HES) by the MicroPicell platform (Université de Nantes). Images were captured using Nanozoomer slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics). A scoring was done by an anatomopathologist in a blinded manner. Villi, apoptosis of the crypts, regeneration of the crypts, loss of the crypts, inflammation of the chorion, and mucosal ulceration from the small intestine were scored from 0 to 4 according to the level of lesions.

Skin graft on GVHD long survivor rats

GVHD F1 Lew/BN long survivor rats (>day 120 after GVHD induction) were grafted on their back with full skin from Lew, BN, and third-party Sprague-Dawley rats. Graft rejection was scored every day from day 0 to day 50.

GVT model in immune-humanized NSG mouse

A total of 5 × 106 MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were injected subcutaneously in 100 μL of PBS into the flank of male NSG mice (8 to 12 weeks old). When the tumor was detected, 1.5 × 107 PBMCs from a HV donor were injected IV (day 0). Transplanted mice received anti-human CD45RC mAb (ABIS-45RC) every 2.5 days at 0.8 mg/kg per injection intraperitoneally starting from day 0 until day 20 with or without rapamycin orally (0.4 mg/kg per day for 10 days). Body weight and tumor size were measured twice per week for 60 to 70 days, and mice were euthanized when percentage of weight loss was ≥20% of their initial weight or when the tumor size reached 3000 mm3. Groups of 5 to 10 animals were matched in age, sex, and initial weight and randomly treated. Tumor volume was calculated using the following formula18: V = π/6 × f(length × width)3/2; females: f = H/LW = 1.58 ± 0.01; males: f = H/LW = 1.69 ± 0.03.

Cohort of cord blood–grafted patients

The expression of CD45RC on PBMCs was analyzed from cryopreserved samples among a cohort of 88 recipients of an unrelated double cord blood transplantation (UCBT). All recipients were included in a clinical trial assessing the role of double UCBT in patients with de novo or secondary AML aged between 15 and 65 years.19 All received the same conditioning regimen, consisting of cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg per day on day −6, fludarabine 40 mg/m2 per day from day −6 to day −2, and TBI at 2 Gy at day −1 and GVHD prophylaxis regimen consisting of cyclosporine with mycophenolate mofetil. Cyclosporine was started at day −3 and maintained until day +100, then it was slowly tapered until 6 months and stopped in absence of GVHD. MMF was started at day −3 at 30 mg/kg per day and stopped at day +30. CD45RC expression on T cells was analyzed in patients before the graft, and 3 and 24 months after the graft.

mAbs and staining

PBMCs from rats in aGVHD model were analyzed at days 7, 15, 22, and 50 to follow engraftment of injected cells. PBMCs were stained with anti-CD3 (R7/3 APC [allophycocyanin]), anti-CD4 (OX35 PeCy7), and anti-CD45RC (OX32 PE [phycoerythrin]). Anti-rat major histocompatibility complex class I and II (MHC-I and MHC-II) RT1n (recognizing the n MHC expressed by F1 recipient Lew/BN cells; biotin plus streptavidin PerCP) and RT1l (recognizing the l MHC-I expressed by F1 recipient Lew/BN and Lew donor cells; fluorescein isothiocyanate) were used to distinguish injected T cells from recipient cells.

For mouse cells, splenocytes or PBMCs were stained with anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD25 (PC61), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD19 (ID3), anti-CD49b (DX5), anti-CD11c (HL3), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-Ly6c (AL-21), and anti-CD45RC (DNL1.9) mAbs from BD Biosciences. Cells were further fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-Foxp3 mAb (MF23; BD Biosciences). The fluorescence was measured with a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience); FlowJo software was used to analyze data. Cells were first gated on their morphology and then dead cells were excluded by staining with fixable viability dye.

For human cells, 50 µL or 100 μL of fresh EDTA whole blood were stained with combinations of appropriate mAbs (supplemental Tables 2 and 3), followed by erythrocyte lysis (versalyse; Beckman Coulter). After washing, cells were analyzed on a Navios flow cytometer and data analyzed using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter) and FlowJo software.

Cell death assay

Splenocytes, purified by negative selection, from mice were incubated with medium, isotype control Ab (clone 3G8 or R35-95, 10 µg/mL), dexamethasone (20 µg/mL), or anti-CD45RC mAbs (clone DNL1-9, 10 µg/mL) for 1 to 18 hours. Then, cells were stained with anti-CD3 (145-2C11) and anti-CD45RC (3H1437) mAbs, annexin V (BD Biosciences), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Percentage of late apoptosis was obtained by gating on DAPI+ annexin V+ cells among CD45RC+ T or non-T cells by flow cytometry.

Human PBMCs were incubated with medium, isotype control Ab (clone 107.3, 10 µg/mL), ATG (Thymoglobuline; 20 µg/mL; Sanofi) or anti-CD45RC mAb (clone ABIS-45RC, 10 µg/mL) for 1 to 18 hours. Then, cells were stained with anti-CD3 (clone SK7; BD Biosciences), annexin V and DAPI. Percentage of apoptosis was obtained by gating on DAPI+ Annexin V+ cells among T or non-T cells by flow cytometry.

Detection of T-cell activation by CMV in the presence of anti-human CD45RC ABIS-45RC mAbs

PBMCs from healthy volunteers that were seropositive for previous CMV infection or not were cultured in complete medium, comprising VLE-RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with stable glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (all from Biochrom) and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (PAA). This study was approved by the Charité University Medicine Ethical Committee (Institutional Review Board). Informed consent was documented. Freshly isolated PBMCs were stimulated for 14 hours with overlapping CMVpp65/IE-1 peptide pools (15 mers, 11-aa overlap; JPT Peptide Technologies) at 1 μg/mL each peptide or 1 μg/mL Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB) superantigen (Sigma) in the absence or presence of ABIS-45RC mAb at 10 µg/mL. For functional and phenotypic characterization, 5 × 106 PBMCs per 1 mL of complete medium were stimulated in polystyrene round bottom tubes (Falcon; Corning) at 37°C in humidified incubators and 5% CO2.

For analysis of antigen-induced intracellular CD137 expression and IFN-γ production, we added 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Sigma) for the last 12 hours of stimulation. After harvesting, extracellular staining was performed using fluorescently conjugated monoclonal antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes. To exclude dead cells, LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain dye (Invitrogen) was added. After washing, we stained fixed cells at 4°C with the following fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs for 30 minutes: anti-CD3 (BV650, clone OKT3), anti-CD4 (PerCp-Cy5.5, clone SK3), anti-CD8 (BV570, clone RPA-T8), anti-CD137 (phycoerythrin-Cy7, clone 4B4-4), and anti–IFN-γ (BV605, clone 4S.B3). All antibodies were purchased from BioLegend, unless indicated otherwise. Cells were analyzed on a LSR-II Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo version 10 software (Tree Star). For ex vivo analysis, at least 2 × 106 events were recorded. Lymphocytes were gated based on the forward scatter (FSC) vs side scatter (SSC) profile and subsequently gated on FSC (height) vs FSC to exclude doublets. Unstimulated PBMCs were used as controls and respective background responses were subtracted from antigen-reactive cytokine production. Negative values were set to 0. Measurements were performed in the immunologic study laboratory of the BCRT.

TNF-α cytokine release assay in the presence of anti-CD45RC mAbs

TNF-α release was assessed using human PBMCs (106 per well) from freshly isolated PBMCs ex vivo or rested in preculture at high density (107 per well) for 24 hours. PBMCs were then cultured in RPMI medium (10% fetal calf serum) and nonstimulated, or stimulated with either 50 µg/mL ABIS-45RC mAb, 50 µg/mL isotype control mAb, or 1 µg/mL OKT3 mAb for 24 hours at 37°C. TNF-α release was detected by applying the Ella-system assay (ProteinSimple) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For each sample respective OD values of TNF-α concentration calculated based on a calibration curve were obtained by subtracting the blank provided by the vendor. The mean concentrations and standard deviations of the samples were calculated. Measurements were performed in the immunologic study laboratory of the BCRT.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prims (GraphPad Software Inc) and represented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) with *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001. Differences between groups were assessed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), nonparametric Bonferroni posttest. Survival was analyzed by Mantel Cox, log-rank test.

Experimental procedures were specifically approved by the local ethic committee (nos. APAFIS# 3143 for rat and 2525 for NSG mice). Experimental procedures were specifically approved by the local ethic committee (no. APAFIS#11511-2017092610086943). This study was approved by the internal review board of Hôtel-Dieu Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris.

Results

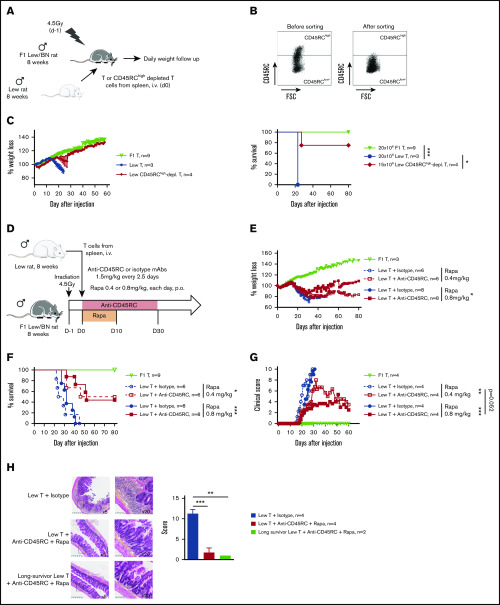

Ex vivo or in vivo CD45RC targeting prevents aGVHD and induces donor-specific tolerance in F1 Lew/BN rats

To address CD45RC targeting potential in aGVHD, we set up a new model of semi-allogeneic aGVHD with adoptive transfer of total T cells of Lew origin (RT1l) into Lew/BN (RT1l/n) rats and assessed the weight loss and survival of the recipients (Figure 1A). The injection of 15 × 106 enriched Lew T cells (purity > 80%) was sufficient to induce a reproducible weight loss in all treated animals, whereas recipients injected with <10 × 106 Lew T cells or 20 × 106 F1 Lew/BN T cells as control did not lose weight nor develop aGVHD (supplemental Figure 1A). To determine the potential of targeting CD45RC on total T cells in aGVHD, we first used a protocol where CD45RChigh cells were ex vivo depleted from total T cells and the subsequent sorted CD45RClow/− cells (Figure 1B) adoptively transferred. Infusion of CD45RChigh-depleted Lew T cells resulted in absence of weight loss and indefinite allograft survival in most of the recipients, whereas animals adoptively transferred with total T cells lost weight and all died by day 20 after injection (Figure 1C), showing that CD45RChigh cells are necessary for the induction of aGVHD and elimination of these cells results in inhibition of aGVHD.

Figure 1.

Ex vivo or in vivo depletion of CD45RChighT cells associated with a suboptimal dose of rapamycin induces long-term survival in a model of aGVHD in F1 Lew/BN rats. (A) Schematic of the protocol: 8-week-old F1 male Lew/BN (RT1l/n) rats, obtained following crossing of Lew (RT1l) female and BN (RT1n) male rats, were irradiated 4.5 Gy 1 day before being transferred with total T cells or CD45RChigh-depleted T cells enriched from Lew splenocytes. (B) Splenocytes were stained for CD45RC with an anti-CD45RC mAb (OX32) (y-axis) before sort and after depletion of CD45RChigh cells and cell sorting using the anti-CD45RC mAb OX22 clone binding a distinct epitope than OX32. (C) F1 rats received either 20 × 106 F1 or Lew T cells or 15 × 106 Lew T cells. Results are expressed in percentage of weight loss for each recipient and percentage of survival. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA and log rank (Mantel Cox) tests. *P < .05; ***P < .001. Two independent experiments. (D) Schematic of the protocol: Lew or Lew/BN F1 T cells enriched from splenocytes were transferred (20 × 106) into irradiated (d-1) F1 rats. Recipients were treated with anti-rat CD45RC mAbs (n = 6-8) or isotype control mAbs (n = 6-8) every 2.5 days for 30 days in association with suboptimal doses (0.4 or 0.8 mg/kg) of rapamycin each day for 10 days. Results are expressed in mean percentage of weight loss (E) and survival (F). Four independent experiments. (G) Animals were assessed at different times after injection for a clinical score of aGVHD (see supplemental Table 1) and euthanized at score 10. Two independent experiments. (H) Histological analysis of small intestine (ileum) and scoring of lesions was performed at day 28 in rats treated with isotype control or anti-CD45RC mAb and rapamycin or in long survivors rats at day 150 (original magnification ×5 and ×20). The black squares indicate the zone of ×20 magnification. Results are expressed in mean ± SEM. **P < .01; ***P < .001. depl., depleted; FSC, forward scatter; p.o., per os (orally).

To further determine the potential of the depleting anti-CD45RC mAbs as a treatment of aGVHD, we treated Lew/BN rats injected with 20 × 106 Lew T cells with transient administration (from day 0 to day 30) of anti-CD45RC or isotype control mAbs alone or in conjunction with 2 different suboptimal doses of rapamycin (ie, 0.4 mg/kg per day and 0.8 mg/kg per day from day 0 to day 10) (Figure 1D). Although transient anti-CD45RC mAbs alone treatment did not delay significantly aGVHD (supplemental Figure 1B), suboptimal dose of rapamycin in combination with anti-CD45RC mAbs resulted in a synergistic inhibition of aGVHD development and even induction of long-term survival in 50% of the recipients for both doses of rapamycin (Figure 1E-F). Rapamycin in combination with isotype control mAbs did not delay GVHD occurrence (Figure 1E-F). In the groups cotreated with anti-CD45RC mAbs and rapamycin, we observed that, although all recipients developed clinical signs of aGVHD, recipients that received 0.8 mg/kg rapamycin together with anti-CD45RC mAbs developed less clinical symptoms in terms of weight loss and recovered faster compared with the other groups (Figure 1G). Anti-CD45RC mAb-treated recipients were efficiently depleted in CD45RChigh T cells as showed by flow cytometry in the blood at day 10 (supplemental Figure 1C). Histological analysis of the small intestine showed strong infiltration and lesions in isotype control mAb-treated recipients, whereas rats treated with the anti-CD45RC mAb and rapamycin showed low infiltration and absence of lesions at early and late time points as shown by the histological scoring (Figure 1H).

We then analyzed the engraftment of donor cells at different time points following injection of T cells in the recipients using the haplotype markers for donors (RT1l+) or F1 recipients (RT1l+/n+) (Figure 2A). We observed that in the blood, engraftment of donor cells increased with time as shown by the percentage of donor RT1l+ RT1n− cells (Figure 2B). We observed no correlation between engraftment and the treatment or the GVHD occurrence. In the peripheral blood of animals that survived >50 days, cells were of donor origin, suggesting a complete tolerance of engrafted cells (RT1l) toward recipient antigens (RT1l/n). Analysis of absolute number of cells in spleen, blood, BM, and lymph node of F1 recipient, long survivor F1 rat transferred with F1 T cells or long survivor F1 rat transferred with Lew T cells and treated with anti-CD45RC mAb and rapamycin, showed significantly less cells in spleen and lymph nodes of tolerant Lew T-cell transferred F1 recipients treated with anti-CD45RC and rapamycin compared with the other groups (Figure 2C), suggesting that anti-CD45RC mAb decreased the proliferation of engrafted cells. This decrease reflected a global decrease of all cell subsets in spleen, blood, and lymph nodes, with in particular a decrease in T, B, granulocytes, and MDSC cells (supplemental Figure 2). In contrast, we observed an increase of all subsets in the BM (supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Anti-CD45RC mAb and rapamycin treatment induces tolerance in T-cell transferred Lew/BN F1 rats. (A) Control staining was realized on Lew (RT1l), BN (RT1n) and F1 Lew/BN (RT1l/n) PBMCs using anti-RT1l and anti-RT1n antibodies. (B) Top, Representative staining with anti-RT1n and anti-RT1l mAbs at different time points (days 7, 15, 22, and 50) on PBMCs of Lew/BN F1 rats injected with 2 × 107 Lew T cells and treated either with anti-CD45RC mAbs or isotype control mAbs and a suboptimal dose of rapamycin. Bottom, Results are expressed in mean of percentage of RT1n-RT1l+ cells among PBMCs ± SEM. Three independent experiments. (C) Absolute number of cells in spleen, blood (PBMC), BM, and lymph node (LN) were analyzed in Lew/BN F1 rats, long survivor rats transferred with either Lew/BN F1 T cells or Lew T cells and treated with anti-CD45RC mAbs and rapamycin. **P < .01; ***P < .001. (D) Long survivor F1 rats (>day 120) transferred with Lew T cells and treated with anti-CD45RC mAbs and rapamycin were grafted with Lew (donor), BN (recipient), and SPD (third-party) skins. Grafts were scored daily from 0 (nonrejected graft) to 3 (rejected graft). Bonferroni posttest. *P < .05; **P < .01.

To further test the hypothesis of a donor MHC-specific tolerance in Lew T-cell fully engrafted recipients, the long-surviving recipients (>120 days) were transplanted with skin from donor type (Lew, RT1l), recipient type (BN, RT1n), and third-party type (SPD, RT1u) and monitored for skin-graft rejection (Figure 2D). Although donor and recipient type skin grafts were completely tolerated and only reached score 1 reflecting a normal dryness of the skin, third-party SPD skin grafts were rejected in all the recipients, as shown by the skin-graft rejection score (Figure 2D), thus demonstrating that anti-CD45RC mAb treatment resulted in induction of donor MHC-specific tolerance in all recipients.

Anti-mouse CD45RC mAb delays aGVHD following BMT in mice

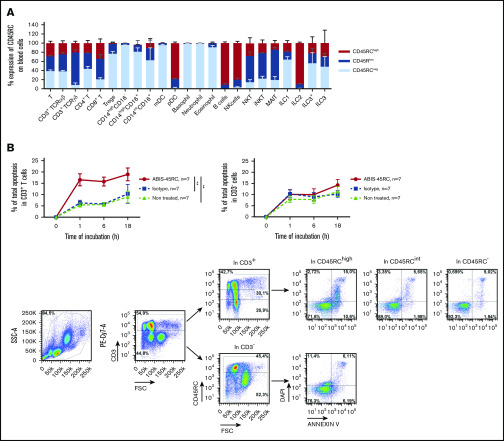

To reinforce the solidity of our observations and to validate our approach in another animal species, we tested the anti-CD45RC mAb strategy in a BMT model in mice. We first analyzed the expression of CD45RC in mice using the anti-mouse CD45RC mAb (DNL1.9 clone) and observed, as in the rat and human, that CD45RC is mostly expressed by T, B, NK cells, and pDCs (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 3). We then assessed the potential of the anti-mouse CD45RC mAb to induce CD45RC+ cell death as previously observed in rat and human.9 Here again, the anti-mouse CD45RC mAb induced an efficient and rapid CD45RC+ T-cell death in vitro as shown by the annexin V and DAPI staining (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Anti-mouse CD45RC mAb treatment alone delays GVHD following BM and T-cell administration. (A) Percentages of CD45RC+ cells among mouse splenocytes. Cells were first gated on morphology, doublet cells, and live cells. Mean expression of CD45RC ± SEM on different cell types (n = 3). (B) Mouse splenocytes incubated with anti-CD45RC or isotype control mAbs or dexamethasone as a positive control were stained with annexin V to analyze apoptosis. Results show the percentage expression of annexin V+ DAPI+ cells among CD45RC+ T cells for 1 to 18 hours compared with controls. **P < .01. (C) T cells were injected into irradiated mice at time of BM transfer (BM group n = 4). Mice were treated with anti-CD45RC (n = 11) or isotype control (n = 11) mAbs. Experiments were performed twice and data were pooled. Survival (D) and GVHD clinical score (E) were analyzed every day. *P < .05; **P < .01. (F) Histogram shows area under curve (AUC) of clinical GVHD. AUC was calculated for each mouse, and then an ANOVA test with post hoc analysis was performed. **P < .01.

We then investigated the efficacy of the anti-CD45RC mAb in a model of aGVHD consisting in administering bone marrow with CD3+ T cells from B6 mice into lethally irradiated F1 B6×C3H recipient mice (Figure 3C). In this model, anti-CD45RC mAb treatment was efficient alone in delaying aGVHD and significantly prevented death in 20% of the animals showing indefinite survival (Figure 3D) and improved clinical grade of the GVHD (Figure 3E-F), in contrast to the isotype control group. In the 2 long surviving recipients treated with anti-CD45RC mAb, analysis of the skin, lung, liver, and small intestine showed no or little lesions of the organs (data not shown).

Altogether, the results in rats and mice show the potential of the anti-CD45RC mAb treatment to prevent GVHD in rodents and induce tolerance. They also show that anti-CD45RC mAb treatment did not inhibit engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells but rather decreased the effector T-cell pool.

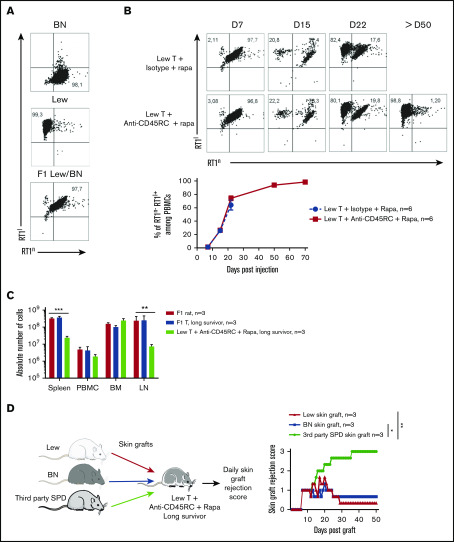

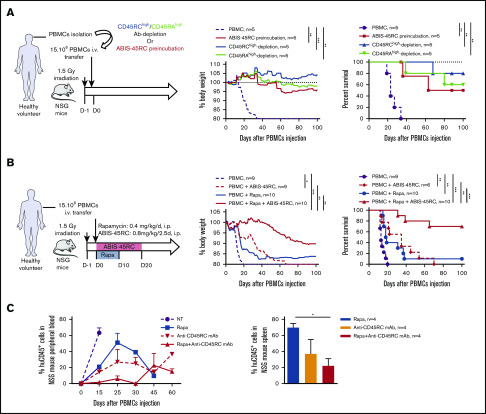

A chimeric anti-human CD45RC mAb induces human CD45RChigh T-cell death and inhibits aGVHD in NSG-humanized mice

To determine the potential of anti-CD45RC mAb in preventing aGVHD in human, we used a chimeric (V mouse–IgG1 human Fc) anti-human CD45RC mAb (clone ABIS-45RC) in a model of xenogeneic GVHD in immunodeficient NSG mice. First, the expression of CD45RC using the ABIS-45RC mAb was analyzed on leukocyte subsets in total blood from healthy individuals. We observed that CD45RC is mostly expressed by αβ and γδ T cells (CD4+ and CD8+), pDC, B cells, NK cells, and ILC2 (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 4). As previously shown in rats,9 the anti-human CD45RC mAb specifically induced apoptosis of T cells (Figure 4B left), but not of non-T cells (Figure 4B right). Immunohistology performed with ABIS-45RC in 10 different human tissues (including secondary lymphoid tissues, heart, brain cortex, lung, kidney, small intestine, colon, liver, and pancreas) showed positivity only in delimited areas of secondary lymphoid tissues and in lymphoid structures in the intestine and no off-binding reactivity on human parenchymal cells (supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 4.

ABIS-45RC chimeric anti-human CD45RC mAb induces cell death of CD45RChighT cells. (A) Expression levels of CD45RC using ABIS-45RC mAb on different human leukocyte subsets. Staining with ABIS-45RC was realized in whole blood (EDTA) from healthy volunteers after lysis of red blood cells before cytometry analysis. Cells were first gated on morphology, singlet cells, and live cells. Mean expression ± SEM of CD45RChigh, CD45RClow, and CD45RC− on different cell types (n = 3) (1 experiment). (B) Human PBMCs incubated at 37°C with 10 µg/mL ABIS-45RC or isotype control mAbs were stained with annexin V and DAPI to analyze apoptosis. Results are expressed as relative proportion of annexin V+ cells among CD3+ cells (left) or CD3− cells (right) for 1 to 18 hours. A representative staining of ABIS-45RC on the different populations analyzed is shown (bottom). **P < .01.

We then tested ABIS-45RC mAb in vivo by either depletion of the donor cells before injection or direct administration of ABIS-45RC mAb (Figure 5). We first assessed the potential of ABIS-45RC mAb to prevent aGVHD when used before administration of the donor cells either by incubation (ABIS-45RC preincubated) or after cell sorting depletion (Ab depletion), as it has been described for the anti-CD45RA mAb20 (Figure 5A left). Preincubation or depletion by cell sorting using ABIS-45RC led both to significant inhibition of GVHD occurrence in 50% to 80% of the mice as shown by body weight and survival curves of the mice (Figure 5A middle and right) without inhibiting human cell engraftment (supplemental Figure 6A). Depletion using anti-CD45RA mAb also resulted in aGVHD prevention in 60% of the mice, however, 50% of mice that received PBMCs depleted in CD45RAhigh cells finally developed chronic GVHD at distance of transplantation in contrast to mice that received PBMCs depleted in CD45RChigh cells that did not develop signs of GVHD.

Figure 5.

Anti-human CD45RC ABIS-45RC treatment improves aGVHD survival in immune-humanized NSG mice. (A) Total human PBMCs or PBMCs depleted in CD45RChigh or CD45RAhigh or preincubated with anti-CD45RC mAb were transferred in irradiated NSG mice to induce GVHD. Results are expressed in percentage of weight loss (left) and mice survival (right) (2 experiments). **P < .01; ***P < .001. (B) NSG mice transferred with total human PBMCs to induce GVHD were treated with anti-CD45RC (ABIS-45RC) mAb alone or with a suboptimal dose of rapamycin for the indicated time points. Results are expressed in percentage of weight loss (left) and mice survival (right) (4 experiments). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (C) Histogram of the percentage of human CD45+ cells in NSG mice peripheral blood (left) and spleen (right) (days 15, 25, 30, 45, and 60 for peripheral blood and day 25 for spleen). *P < .05.

ABIS-45RC mAb was then directly injected in the humanized NSG mice, starting from day 0 to day 20 alone or in combination with a suboptimal dose of rapamycin given during 10 days (Figure 5B left). ABIS-45RC mAb alone was able to significantly delay the GVHD occurrence in a similar manner than low dose of rapamycin (Figure 5B middle and right). Combination of low dose rapamycin and ABIS-45RC mAb resulted in a significantly delayed xenogeneic GVHD and even induction of indefinite survival in 70% of the recipients, confirming a synergistic potential of both compounds as observed in rats. In addition, we observed decreased infiltration and lesions of liver and kidney in particular in recipients treated with ABIS-45RC mAb and rapamycin (Figure 5C). In mice treated with rapamycin or ABIS-45RC mAb alone, we observed a similar percentage in both blood and spleen of huCD45+ cells, however we observed a decreased percentage in the group treated with both rapamycin and ABIS-45RC mAb (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 6B), suggesting that the efficacy of the combination is associated to a mechanism of suppression of the proliferation of effector human PBMCs.

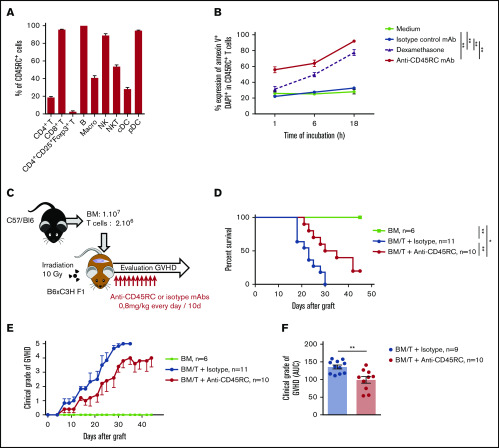

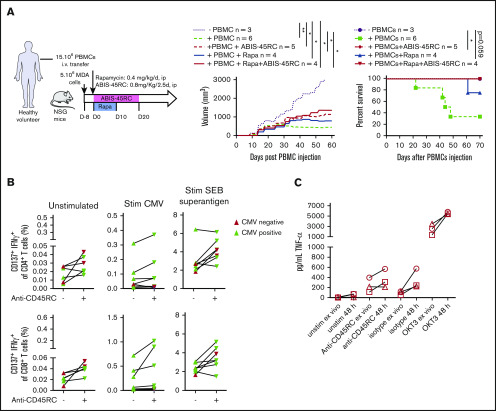

ABIS-45RC mAb preserves the GVT and antiviral memory immune responses and does not induce a cytokine release syndrome

To further evaluate the safety profile of ABIS-45RC mAb therapy in humans, we analyzed the GVT response in a model using a human breast cancer cell line (MDA cells) in humanized NSG mice (Figure 6A). MDA cells were implanted 8 days before the injection of human PBMCs and the beginning of the treatment. In these setting, tumors were detectable. Although in the absence of human cells the tumor grew, when PBMCs were injected alone or in combination with ABIS-45RC mAb, rapamycin low dose or with combination of ABIS-45RC mAb and rapamycin, the tumor showed a delayed growth (Figure 6A left), suggesting that ABIS-45RC mAb did not impair the GVT effect. Analysis of GVHD occurrence in this model without irradiation showed that the mice injected with PBMCs and PBMCs + Rapa developed GVHD in 70% of the cases, whereas the mice injected with ABIS-45RC mAb alone or in combination with rapamycin did not develop GVHD (Figure 6A right), suggesting that the antibody induces an efficient control of GVHD while preserving GVT.

Figure 6.

ABIS-45RC treatment preserves elimination of tumor cells by GVT and memory antiviral immune responses. (A) NSG mice were injected subcutaneously with human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and, when tumor growth was detectable (day 8), were transferred with total human PBMCs to induce GVT. Results are expressed in tumor volume (left) and mice survival (right) (2 experiments). *P < .05; **P < .01. (B) Human PBMCs from CMV+ or CMV− individuals were cultured in medium, with CMV peptides or SEB superantigen with or without ABIS-45RC mAb (n = 7). Cytokine responses were analyzed by flow cytometry on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (1 experiment). (C) TNF-α release by human PBMCs from healthy volunteers cultured for 24 hours with PBMCs at low (106 cells per well) or high density (107 cells per well precultured for the previous 24 hours) with ABIS-45RC, isotype control, OKT3 mAbs, or unstimulated. TNF-α release was detected by applying the Ella-system assay (1 experiment).

To determine how the T-cell memory responses in human cells could be impacted by the antibody treatment, we analyzed CD4+ and CD8+ T cells responses from CMV+ and CMV− patients in the presence of different stimulations (ie, CMV or SEB superantigen). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from CMV+ patients incubated with ABIS-45RC mAb were able to respond to the CMV stimulation, upregulated CD137 and produced IFNγ (Figure 6B), whereas CMV− patients did not. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from CMV+ or CMV− patients were equally activated following stimulation with the SEB superantigen. Altogether, this demonstrates that the memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells specific for CMV were not depleted by the anti-CD45RC mAb.

The ABIS-45RC mAb has the capacity to deplete a subpopulation of T cells. Here, we evaluated whether it could deplete T cells following a phase of strong activation potentially leading to the so-called cytokine release syndrome observed in patients receiving immunotherapy. For this, we assessed cytokine release in the supernatant of culture following incubation of PBMCs with ABIS-45RC. To increase the sensitivity of the assay we cultured the PBMCs at high density of cells for 48 hours before the addition of the different antibodies. We observed that, in contrast to an anti-CD3 (OKT3 clone) mAb that induces a high release of TNFα cytokine in the supernatant and is known to induce a cytokine release syndrome in humans, we only observed a marginal and comparable increase in the levels of TNFα in the supernatant following incubation of the PBMC cells with both the ABIS-45RC mAb or an isotype control mAb (Figure 6C).

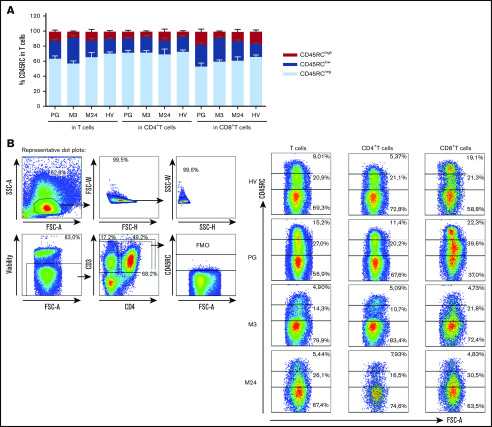

Finally, we tested whether CD45RC could be a reliable target of immunotherapy in the setting of HSCT. For this, we compared CD45RC expression in the BM, in the blood of donors of recipient pregraft (PG) as well as in grafted patients at month 3 (M3) and M24. We observed that CD45RC was not expressed by CD34+ BM cells (data not shown), whereas it was expressed by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells similarly to healthy individuals in HST transplanted patients before graft (PG) or after graft at month 3 or month 24 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

CD45RC expression is not altered before and after HSCT. (A) Expression level of CD45RC was analyzed on human T cells from PBMCs from healthy individuals or 88 patients between 15 and 65 years of age with de novo or secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) before (pregraft [PG]) hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or at month 3 (M3) and month 24 (M24) after HSCT. Mean expression ± SEM of CD45RChigh, CD45RClow, CD45RC− at the different times analyzed. (B) Representative staining is shown. Cells were first gated on morphology, singlet cells, live cells, and CD3+ cells. FMO, Fluorescence Minus One control; FSC-A, forward scatter area; FSC-H, FSC height; SSC-A, side scatter area; SSC-H, SSC height.

Discussion

Our results show that a prophylactic treatment with different anti-CD45RC mAbs specific of rat, mouse, or human molecules prolonged survival alone or in combination with a suboptimal dose of rapamycin in 3 different models of aGVHD mediated by Teff cells. Clinical BMT is mostly performed between MHC-compatible individuals (with minor histocompatibility antigens mismatches) and increasingly with hemi-incompatible ones (haploidentical, half HLA haplotype mismatch).21 In this manuscript, we used F1 hemi-incompatible animal models (mouse and rat) that are representative of the clinical situation and we included a strong xenogeneic model using human cells into NSG mice emphasizing the translational significance of our data. Donor-specific immune tolerance was present and human GVT responses were preserved. We also describe the apoptotic effect in CD45RChigh T cells and the safety profile of the anti-human CD45RC chimeric mAb ABIS-45RC used in the aGVHD NSG model.

Although standard treatments of aGVHD including steroids and a variety of classical immunosuppressors such as MMF or methotrexate in combination with either calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) or rapamycin have been relatively successful at preventing GVHD, their prophylactic effect against severe GVHD occurrence is not always obtained.2 Addition of antibodies aiming to deplete donor T cells to these standard prophylactic treatments before or immediately after BMT has been developed. These antibodies include pan-depleting lymphocytes such as polyclonal ATG and mAbs directed against CD52 with mixed results because, although in some studies using prophylactic in vivo treatment the frequency and severity of aGVHD were reduced, they were also associated with increased incidence of malignancies relapse and infection episodes.22 In a similar strategy of lymphoid cell depletion, the BM graft has been depleted of lymphoid cells before transplantation to prevent GVHD. Several studies have shown aGVHD prevention by this ex vivo treatment but in some of them also associated to graft failure, relapse, and infections.22 Although these pan-depleting strategies show promise, larger and randomized studies are needed before this approach might become a standard of care for aGVHD prophylaxis because the risks of depleting these large lymphoid cell populations, including not only T but also NK cells, is profound: immunosuppression with increased risk of infections and reduced GVT.

The depletion of more restricted T-cell populations would increase specificity and decrease secondary effects. CD8+ T-cell depletion did not show clinical beneficial effect in a phase 2 study.23 BMT ex vivo depleted of αβ T and B cells with conserved γδ T cells showed clinical benefit in patients with nonmalignant diseases.24 Because naive T cells have been shown to play a major role in aGVHD in rats,4 mice,25,26 and humans,27,28 the use of an anti-CD45RA mAb to deplete those cells from the HSC graft before infusion was assessed; although it did not reduce the incidence of aGVHD, the incidence of cGVHD was decreased.29 It is important to note that the distribution of CD45RA+ cells among T cells also includes a high proportion of CD4+,30 as well as CD8+, FOXP3+ Tregs9; therefore, the depletion of these Tregs could hamper the development of tolerogenic mechanisms. The use of anti-CD45RC mAbs instead of pan-lymphoid–depleting or anti-CD45RA mAbs has the advantage of a favorable cell distribution of CD45RC, which is expressed at high levels on naive CD4+ Th1 precursor cells involved in aGVHD4 and absent in CD4+ and CD8+ Foxp3+ Tregs.5-7,9 Furthermore, ex vivo or in vivo treatment with anti-CD45RC mAbs induces apoptosis in only CD45RChigh T cells but not in CD45RClow/− T cells or in other cells that are also CD45RChigh, such as B cells.9 A depleting drug-conjugated anti-CD30 mAb showed moderate efficacy in aGVHD in patients but with high toxicity.31 Among nondepleting blocking mAbs, anti-CD2632 and anti-CD28 partially prevented xeno-GVHD33 in NSG mice.

Other therapeutic strategies in aGVHD involve Treg cell therapy with in vitro–expanded CD8+ and CD4+ Tregs.34-38 An alternative strategy is to increase endogenous CD8+ and CD4+ Treg function and numbers through the administration of low doses of IL-2 acting through the high-affinity IL-2R,39-41 although this treatment can also activate Teff cells.39 Low-dose IL-2 has been used in both aGVHD rodent models and patients receiving HLA-matched BMT as prophylactic as well as therapeutic treatments with beneficial effects on some,42,43 but not all, clinical studies.44 Although increasing Treg global activity has shown preliminary positive results in animal models and small clinical studies, it remains to be confirmed in large series and has the potential disadvantage that effector T cells are not depleted; because Tregs are plastic in inflammatory conditions, they may convert in potentially pathogenic cells.45 In comparison, anti-CD45RC mAb treatment was shown to deplete CD45RChigh pathogenic T cells, allowing amplification and activation of donor-specific CD8+ and CD4+ CD45RClow/− Tregs in a model of solid-organ transplantation.9 In the same aGVHD rat model used in the present study, Saoudi’s group showed that adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RChigh T cells was pathogenic whereas both CD4+ or CD8+ CD45RClow Tregs were protective.4,7

The anti-CD45RC mAb treatment was synergistic with a low-dose rapamycin treatment. Calcineurin inhibitors used for both prevention and treatment of aGVHD decrease Teff cell responses at least partially by reduction of IL-2 production,1,2 but this also results in decreased Treg function and survival.46 In opposition to calcineurin inhibitors, rapamycin does not inhibit IL-2 action on Treg function and promotes the expansion of both CD4+47 and CD8+ Tregs13 and has shown beneficial effects both in rodent models and in the clinical treatment of aGVHD.48,49

The present results on skin transplantation in a rat aGVHD model showing, in long surviving animals, specific absence of immune responses against recipient antigens, and not against a third-party skin donor, demonstrates the presence of tolerogenic mechanisms. The conserved immune GVT responses in animals treated with ABIS-45RC mAbs with or without rapamycin also supports the notion that these animals show a donor alloantigen-specific tolerance and not global immunosuppression. Although we assessed immune responses against solid tumor cells, they are not intrinsically or essentially different than those against a leukemic cell and allowed demonstration of GVT immune-response conservation. Furthermore, the preservation of human memory antiviral Teff cell responses in the presence of anti-CD45RC mAbs gives additional safety data for a selective depletion of CD45RChigh T cells without affecting all immune responses. Although an in vivo model would be more suitable in testing how the ABIS-45RC antibody affects antiviral memory T-cell immunity, our applied in vitro approach is robust and validated for memory anti-CMV immune responses50-52; in the past, we could also show with this assay that antiviral (BKV) T-cell responses were blocked with immunosuppressive drugs or anti-CD25–blocking antibodies.53,54 Finally, the absence of cytokine release when cells are incubated with anti-CD45RC mAbs is also concurrent with a satisfactory safety profile for this treatment.

In conclusion, anti-human CD45RC mAb treatment of aGVHD has potential use in the clinic as a new prophylactic treatment.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Leila Amini and Nina Salabert-Leguen for flow cytometry measurements. The authors also thank the Biobanking Department staff of Henri-Mondor Hospital, Créteil, France (Plateforme de Ressources Biologiques des Hôpitaux Universitaires Henri Mondor, ref. BB-0033-0002).

This work was supported by LabEx IGO (project Investissements d’Avenir; ANR-11-LABX-0016-01); Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire–Cesti (project funded by the Investissements d’Avenir; ANR-10-IBHU-005 as well as by Nantes Metropole and Region Pays de la Loire); the Agence National de la Recherche (ANR) COLT-45RC (18-CE18-0024-02); the Agence de la Biomedecine; the Fondation Centaure; and the SATT Ouest Valorisation.

Footnotes

Data from the patient cohort have been presented with no overlaps to the present study in: Rio B, Chevret S, Vigouroux S, et al. Decreased nonrelapse mortality after unrelated cord blood transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia using reduced-intensity conditioning: a prospective phase II multicenter trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):445-453.

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the corresponding authors, Carole Guillonneau and Ignacio Anegon, at carole.guillonneau@univ-nantes.fr and ignacio.anegon@univ-nantes.fr.

Authorship

Contribution: L.B., M.-D.L.R., A.T., S.B., M.S.-H., C.B., N.V., A.F., E.A., and F.C. performed research and analyzed data; R.R., F.B., M.L., E.P., R.J., H.-D.V., S.M., and J.L.C. contributed vital reagents or sample collection; and C.G. and I.A. designed, funded, led, and analyzed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.G. and I.A. have patents and ownership interests in start-up company AbolerIS Pharma. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ignacio Anegon, Centre de Recherche en Transplantation et Immunologie, ITUN, UMR 1064, INSERM/Université de Nantes, 44093 Nantes, France; e-mail: ianegon@nantes.inserm.fr; and Carole Guillonneau, Centre de Recherche en Transplantation et Immunologie, ITUN, UMR 1064, INSERM/Université de Nantes, 44093 Nantes, France; e-mail: carole.guillonneau@univ-nantes.fr.

References

- 1.Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(6):443-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Servais S, Beguin Y, Delens L, et al. . Novel approaches for preventing acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(8):957-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedros C, Papapietro O, Colacios C, et al. . Genetic control of HgCl2-induced IgE and autoimmunity by a 117-kb interval on rat chromosome 9 through CD4 CD45RChigh T cells. Genes Immun. 2013;14(4):258-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xystrakis E, Bernard I, Dejean AS, Alsaati T, Druet P, Saoudi A. Alloreactive CD4 T lymphocytes responsible for acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease are contained within the CD45RChigh but not the CD45RClow subset. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(2):408-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillonneau C, Hill M, Hubert FX, et al. . CD40Ig treatment results in allograft acceptance mediated by CD8CD45RC T cells, IFN-gamma, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(4):1096-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xystrakis E, Cavailles P, Dejean AS, et al. . Functional and genetic analysis of two CD8 T cell subsets defined by the level of CD45RC expression in the rat. J Immunol. 2004;173(5):3140-3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xystrakis E, Dejean AS, Bernard I, et al. . Identification of a novel natural regulatory CD8 T-cell subset and analysis of its mechanism of regulation. Blood. 2004;104(10):3294-3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li XL, Ménoret S, Bezie S, et al. . Mechanism and localization of CD8 regulatory T cells in a heart transplant model of tolerance. J Immunol. 2010;185(2):823-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picarda E, Bézie S, Boucault L, et al. . Transient antibody targeting of CD45RC induces transplant tolerance and potent antigen-specific regulatory T cells. JCI Insight. 2017;2(3):e90088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picarda E, Bézie S, Venturi V, et al. . MHC-derived allopeptide activates TCR-biased CD8+ Tregs and suppresses organ rejection. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2497-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ordonez L, Bernard I, L’faqihi-Olive FE, Tervaert JW, Damoiseaux J, Saoudi A. CD45RC isoform expression identifies functionally distinct T cell subsets differentially distributed between healthy individuals and AAV patients. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnier AS, Planchais M, Riou J, et al. . Pre-transplant CD45RC expression on blood T cells differentiates patients with cancer and rejection after kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0214321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bézie S, Meistermann D, Boucault L, et al. . Ex vivo expanded human non-cytotoxic CD8+CD45RClow/- Tregs efficiently delay skin graft rejection and GVHD in humanized mice. Front Immunol. 2018;8:2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bézie S, Anegon I, Guillonneau C. Advances on CD8+ Treg cells and their potential in transplantation. Transplantation. 2018;102(9):1467-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murase N, Starzl TE, Tanabe M, et al. . Variable chimerism, graft-versus-host disease, and tolerance after different kinds of cell and whole organ transplantation from Lewis to brown Norway rats. Transplantation. 1995;60(2):158-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leclerc M, Naserian S, Pilon C, et al. . Control of GVHD by regulatory T cells depends on TNF produced by T cells and TNFR2 expressed by regulatory T cells. Blood. 2016;128(12):1651-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naserian S, Leclerc M, Thiolat A, et al. . Simple, reproducible, and efficient clinical grading system for murine models of acute graft-versus-host disease. Front Immunol. 2018;9:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman JP, Goldwasser R, Mark S, Schwartz J, Orion I. A mathematical model for tumor volume evaluation using two-dimensions. J Appl Quant Methods. 2009;4(4):455-462. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rio B, Chevret S, Vigouroux S, et al. . Decreased nonrelapse mortality after unrelated cord blood transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia using reduced-intensity conditioning: a prospective phase II multicenter trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):445-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Touzot F, Neven B, Dal-Cortivo L, et al. . CD45RA depletion in HLA-mismatched allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for primary combined immunodeficiency: a preliminary study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(5):1303-1309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumeister SHC, Rambaldi B, Shapiro RM, Romee R. Key aspects of the immunobiology of haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Or-Geva N, Reisner Y. The evolution of T-cell depletion in haploidentical stem-cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(5):667-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willems E, Baron F, Baudoux E, et al. . Non-myeloablative transplantation with CD8-depleted or unmanipulated peripheral blood stem cells: a phase II randomized trial. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):608-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Airoldi I, Bertaina A, Prigione I, et al. . γδ T-cell reconstitution after HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation depleted of TCR-αβ+/CD19+ lymphocytes [published correction appears in Blood. 2016;127(12):1620]. Blood. 2015;125(15):2349-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson BE, McNiff J, Yan J, et al. . Memory CD4+ T cells do not induce graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(1):101-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen BJ, Cui X, Sempowski GD, Liu C, Chao NJ. Transfer of allogeneic CD62L- memory T cells without graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2004;103(4):1534-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster AE, Marangolo M, Sartor MM, et al. . Human CD62L- memory T cells are less responsive to alloantigen stimulation than CD62L+ naive T cells: potential for adoptive immunotherapy and allodepletion. Blood. 2004;104(8):2403-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bleakley M, Otterud BE, Richardt JL, et al. . Leukemia-associated minor histocompatibility antigen discovery using T-cell clones isolated by in vitro stimulation of naive CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2010;115(23):4923-4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bleakley M, Heimfeld S, Loeb KR, et al. . Outcomes of acute leukemia patients transplanted with naive T cell-depleted stem cell grafts. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(7):2677-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, et al. . Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30(6):899-911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeFilipp Z, Li S, Kempner ME, et al. . Phase I trial of brentuximab vedotin for steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(9):1836-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatano R, Ohnuma K, Yamamoto J, Dang NH, Yamada T, Morimoto C. Prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease by humanized anti-CD26 monoclonal antibody. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(2):263-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poirier N, Mary C, Dilek N, et al. . Preclinical efficacy and immunological safety of FR104, an antagonist anti-CD28 monovalent Fab’ antibody. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(10):2630-2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazar BR, MacDonald KPA, Hill GR. Immune regulatory cell infusion for graft-versus-host disease prevention and therapy. Blood. 2018;131(24):2651-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, et al. . Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(14):3921-3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koreth J, Matsuoka K, Kim HT, et al. . Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2055-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunstein CG, Miller JS, McKenna DH, et al. . Umbilical cord blood-derived T regulatory cells to prevent GVHD: kinetics, toxicity profile, and clinical effect. Blood. 2016;127(8):1044-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trzonkowski P, Bieniaszewska M, Juścińska J, et al. . First-in-man clinical results of the treatment of patients with graft versus host disease with human ex vivo expanded CD4+CD25+CD127- T regulatory cells. Clin Immunol. 2009;133(1):22-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbas AK, Trotta E, R Simeonov D, Marson A, Bluestone JA. Revisiting IL-2: Biology and therapeutic prospects. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(25):eaat1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Churlaud G, Pitoiset F, Jebbawi F, et al. . Human and mouse CD8(+)CD25(+)FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells at steady state and during interleukin-2 therapy. Front Immunol. 2015;6:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sykes M, Romick ML, Sachs DH. Interleukin 2 prevents graft-versus-host disease while preserving the graft-versus-leukemia effect of allogeneic T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(15):5633-5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuoka KI. Low-dose interleukin-2 as a modulator of Treg homeostasis after HSCT: current understanding and future perspectives. Int J Hematol. 2018;107(2):130-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy-Nasser AA, Ku S, Castillo-Caro P, et al. . Ultra low-dose IL-2 for GVHD prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation mediates expansion of regulatory T cells without diminishing antiviral and antileukemic activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(8):2215-2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Betts BC, Pidala J, Kim J, et al. . IL-2 promotes early Treg reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2017;102(5):948-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hori S. Lineage stability and phenotypic plasticity of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2014;259(1):159-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeiser R, Nguyen VH, Beilhack A, et al. . Inhibition of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell function by calcineurin-dependent interleukin-2 production. Blood. 2006;108(1):390-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Roncarolo MG. Rapamycin selectively expands CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2005;105(12):4743-4748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abouelnasr A, Roy J, Cohen S, Kiss T, Lachance S. Defining the role of sirolimus in the management of graft-versus-host disease: from prophylaxis to treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(1):12-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satake A, Schmidt AM, Nomura S, Kambayashi T. Inhibition of calcineurin abrogates while inhibition of mTOR promotes regulatory T cell expansion and graft-versus-host disease protection by IL-2 in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmueck-Henneresse M, Sharaf R, Vogt K, et al. . Peripheral blood-derived virus-specific memory stem T cells mature to functional effector memory subsets with self-renewal potency. J Immunol. 2015;194(11):5559-5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammoud B, Schmueck M, Fischer AM, et al. . HCMV-specific T-cell therapy: do not forget supply of help. J Immunother. 2013;36(2):93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brestrich G, Zwinger S, Fischer A, et al. . Adoptive T-cell therapy of a lung transplanted patient with severe CMV disease and resistance to antiviral therapy. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(7):1679-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weist BJ, Wehler P, El Ahmad L, et al. . A revised strategy for monitoring BKV-specific cellular immunity in kidney transplant patients. Kidney Int. 2015;88(6):1293-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmueck M, Fischer AM, Hammoud B, et al. . Preferential expansion of human virus-specific multifunctional central memory T cells by partial targeting of the IL-2 receptor signaling pathway: the key role of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(10):5189-5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.