Abstract

This study uses 3D body scanner measurements of US Air Force recruits to compare ideal body proportions represented by Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man with contemporary body proportions in young adult men and women.

Five hundred years ago, Leonardo da Vinci attempted to memorialize Vitruvius’ description of man’s ideal human body. To do this, he manually measured proportions and combined them,1,2 creating one of the most famous drawings of the human body in the world—Vitruvian Man.3,4,5 Today, precise anthropometric body lengths can be obtained rapidly on large numbers of individuals. We repeated his approach using contemporary body scanning measurements to determine what Vitruvius’ proportions would be in this modern data set and how they would appear if drawn in the style of Vitruvian Man. We also extended the process to women.

Methods

Air Force training recruits, typically between the ages of 17 and 21 years, were scanned with the 3-dimensional body scanner (Vitus Smart XXL; Human Solutions) for the purpose of uniform sizing between February 2011 and November 2016 at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Protection Administrator of the US Military Academy. Because of a nonresearch determination, a waiver of consent was granted.

Seven proportions that Leonardo da Vinci identified were available in the body scanner measurements (Table). The same mean proportions and standard deviations were calculated using the body scanner measurements.

Table. Vitruvian Man and Air Force Recruit Body Site Measurements as a Proportion of Height.

| Body lengtha | Vitruvian Man proportion of total height, cm | Proportion of total height, mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| Head height | ⅛ = 0.125 | 0.14 (0.006) | 0.15 (0.008) |

| Arm span | 4/5 = 0.800 | 0.96 (0.027) | 0.92 (0.290) |

| Groin height | ½ = 0.500 | 0.45 (0.016) | 1.46 (0.020) |

| Shoulder width | ¼ = 0.250 | 0.24 (0.013) | 0.25 (0.015) |

| Breast to crown | ¼ = 0.250 | 0.27 (0.008) | 0.28 (0.011) |

| Knee height | ¼ = 0.250 | 0.27 (0.008) | 0.27 (0.075) |

| Thigh length | ¼ = 0.250 | 0.18 (0.011) | 0.18 (0.098) |

To match Leonardo da Vinci’s proportions, some scanner measurements were combined. The scanner did not include hand or foot measurements. In the case of hand measurements, we applied Leonardo da Vinci’s proportion that the hand is one-tenth of body height, so Leonardo da Vinci’s proposed arm span from wrist to wrist should be four-fifths of body height.

All statistical analyses were performed in the statistical program R (R Foundation; 2013).

The scanner-estimated proportions were then applied to draw male and female figures using the same design as Vitruvian Man.

Results

The database of body scanner measurements consisted of 63 623 men and 1385 women. Mean male height was 175.1 cm (SD, 6.8 cm) and female height, 163.7 cm (SD, 6.6 cm).

The derived proportions for head height, arm span, breast to crown, and knee height were slightly more than Leonardo da Vinci’s estimates (Table). The remaining estimates (groin height, shoulder width, and thigh length) were slightly less. Except for arm span and thigh length, the differences in proportions for men measured by the body scanner and Vitruvian Man were within 10%. The difference in arm span was 20% and difference in thigh height was 29% more than Vitruvian Man.

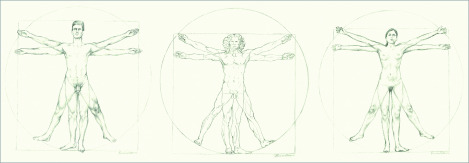

Both male and female drawings (Figure) based on the body scanner data depict arms that reach outside of the square and circle from Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing, while the center of the circle and square are no longer exactly the navel or the groin.

Figure. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man Compared With Contemporary Man and Woman.

Artist drawing of a male (left) and female (right) using the body scanner–derived proportion with a redrawn Leonardo da Vinci Vitruvian Man (center) using the same squares and circles. Some artistic license was applied to generate drawings in realistic poses; however, the proportions of the drawing were checked to ensure they agreed with the proportions obtained from our analysis.

Discussion

Using proportions from a large modern database of automatically scanned anthropometric measurements in both men and women, a contemporary Vitruvian man (and woman) were created, and close agreement with Vitruvian Man was found. All contemporary proportions in men were within 10% of Vitruvian Man except for arm span and thigh length.

Limitations of the study include that a heterogeneous sample of young Air Force recruits was used to estimate the proportions. The sample likely differs from the Tuscan men measured by Leonardo da Vinci, although the exact number and age of individuals he measured is not known. Leonardo da Vinci’s notes and conclusions did not distinguish whether his insights were derived from a single individual or were aggregated.1,2 Also, Vitruvian Man merged the concept of a perfectly proportioned man5 with observed measurements and was not a representation of an average man. In fact, he could not rely on formal notions of population means and variability that were developed only over the last few centuries.6 His notes also did not include measurement precision, and his numerical observations were most likely rounded to the nearest integer. Additionally, the scanner lengths are determined from body reference points, which may differ from his reference points. Despite the different samples and methods of calculation, Leonardo da Vinci’s ideal human body and the proportions obtained with contemporary measurements were similar.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Fairbanks AT, Fairbanks EF. Human Proportions for Artists. Fairbanks Art & Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter JP, Bell RC. The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Dover Publications; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creed JC. Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man. JAMA. 1986;256(12):1541. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03380120011002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lester T. Da Vinci’s Ghost: Genius, Obsession, and How Leonardo Created the World in His Own Image. Free Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacson W. Leonardo da Vinci. Simon & Schuster; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stigler SM. The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty Before 1900. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]