Key Points

Question

What is the accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)–2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening for depression?

Findings

In an individual participant data meta-analysis that included 10 627 participants from 44 studies with semistructured diagnostic interviews, the combination of PHQ-2 (with cutoff ≥2) followed by PHQ-9 (with cutoff ≥10) had a sensitivity of 0.82, specificity of 0.87, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.90.

Meaning

PHQ-2 followed by PHQ-9 may provide acceptable accuracy for screening for depression.

Abstract

Importance

The Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9) is a 9-item self-administered instrument used for detecting depression and assessing severity of depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2) consists of the first 2 items of the PHQ-9 (which assess the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia) and can be used as a first step to identify patients for evaluation with the full PHQ-9.

Objective

To estimate PHQ-2 accuracy alone and combined with the PHQ-9 for detecting major depression.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, PsycINFO, and Web of Science (January 2000-May 2018).

Study Selection

Eligible data sets compared PHQ-2 scores with major depression diagnoses from a validated diagnostic interview.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Individual participant data were synthesized with bivariate random-effects meta-analysis to estimate pooled sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-2 alone among studies using semistructured, fully structured, or Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) diagnostic interviews separately and in combination with the PHQ-9 vs the PHQ-9 alone for studies that used semistructured interviews. The PHQ-2 score ranges from 0 to 6, and the PHQ-9 score ranges from 0 to 27.

Results

Individual participant data were obtained from 100 of 136 eligible studies (44 318 participants; 4572 with major depression [10%]; mean [SD] age, 49 [17] years; 59% female). Among studies that used semistructured interviews, PHQ-2 sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) were 0.91 (0.88-0.94) and 0.67 (0.64-0.71) for cutoff scores of 2 or greater and 0.72 (0.67-0.77) and 0.85 (0.83-0.87) for cutoff scores of 3 or greater. Sensitivity was significantly greater for semistructured vs fully structured interviews. Specificity was not significantly different across the types of interviews. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.88 (0.86-0.89) for semistructured interviews, 0.82 (0.81-0.84) for fully structured interviews, and 0.87 (0.85-0.88) for the MINI. There were no significant subgroup differences. For semistructured interviews, sensitivity for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater followed by PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater (0.82 [0.76-0.86]) was not significantly different than PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater alone (0.86 [0.80-0.90]); specificity for the combination was significantly but minimally higher (0.87 [0.84-0.89] vs 0.85 [0.82-0.87]). The area under the curve was 0.90 (0.89-0.91). The combination was estimated to reduce the number of participants needing to complete the full PHQ-9 by 57% (56%-58%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In an individual participant data meta-analysis of studies that compared PHQ scores with major depression diagnoses, the combination of PHQ-2 (with cutoff ≥2) followed by PHQ-9 (with cutoff ≥10) had similar sensitivity but higher specificity compared with PHQ-9 cutoff scores of 10 or greater alone. Further research is needed to understand the clinical and research value of this combined approach to screening.

This meta-analysis uses individual participant data from diagnostic accuracy studies to estimate the accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2) alone and combined with the PHQ-9 for detecting major depression.

Introduction

In depression screening, questionnaires are used to identify patients with scores above a cutoff threshold for evaluation to determine whether depression is present.1 One strategy is to administer a brief screening tool followed by a longer tool for positive screens.2,3 The Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2),4 which consists of the first 2 items (depressed mood and anhedonia) of the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9),5 has been recommended as a prescreen prior to administering remaining PHQ-9 items (Table 1).2,4,6,7

Table 1. Items Included in the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2) and Full Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9)a.

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Little interest or pleasure in doing thingsb | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | Feeling down, depressed, or hopelessb | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | Feeling tired or having little energy | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | Poor appetite or overeating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | Feeling bad about yourself—or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Or the opposite—being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | |||||

| 9 | Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

The total score for the PHQ-2 and the PHQ-9 are calculated by summing the item scores for the items included in each. The PHQ-9 was developed by Robert L. Spitzer, MD, and colleagues, with an educational grant from Pfizer Inc. The PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 can be found at https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf.

Comprise the PHQ-2.

A 2016 aggregate-data meta-analysis on PHQ-2 accuracy included 21 published studies of the PHQ-28; however, it did not include PHQ-2 data from an additional 37 studies of the PHQ-9.9,10 Except for clinical setting, subgroup results were not reported in primary studies and not evaluated; all primary studies were synthesized regardless of the diagnostic interview used, despite differences in their likelihood of classifying major depression11,12,13; and PHQ-2 accuracy was not evaluated in combination with the PHQ-9, as typically used in practice. Two primary studies14,15 have evaluated the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 combination and produced inconsistent results; one examined score cutoffs for PHQ-2 of 2 or greater and for PHQ-9 of 10 or greater in older community-dwelling adults,14 and the other examined score cutoffs for PHQ-2 of 2 or greater and for PHQ-9 of 6 or greater in patients with acute coronary syndrome.15

The objectives of this meta-analysis of individual participant data were to evaluate PHQ-2 screening accuracy in adults (1) among studies that used different types of reference standards separately; (2) among participants verified as not diagnosed or in treatment vs all participants and by subgroups based on age, sex, country Human Development Index, and recruitment setting; and (3) alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 vs the PHQ-9 alone.

Methods

We published a protocol16 and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42014010673). Results were reported per PRISMA-DTA17 and PRISMA-IPD.18 Previous publications reported PHQ-819 and PHQ-920 accuracy. Individual prediction models described in the protocol will be developed in future studies. Analysis of the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 combination was not prespecified. This study involved analysis of previously collected deidentified data, and included studies were required to have obtained ethics approval and informed consent; thus, the research ethics committee of the Jewish General Hospital determined that ethics approval was not required.

Study Eligibility

Studies were sought with data sets that (1) included PHQ-2 scores or item data to calculate PHQ-2 scores; (2) included current major depressive disorder or major depressive episode classification based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)21,22,23 or International Classification of Diseases (ICD)24 criteria and a validated diagnostic interview; (3) administered the PHQ and diagnostic interview within a 2-week period because diagnostic criteria include only symptoms from the last 2 weeks; (4) included participants 18 years and older not recruited from school or university settings; and (5) did not recruit participants only from psychiatric settings or with depression symptoms because screening is done to identify people not suspected of having depression.25 In data sets where only some participants were eligible, we included only those participants. There were no language restrictions.

Database Searches and Study Selection

The database search was designed by a medical librarian and peer-reviewed26 and included MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations via Ovid, PsycINFO, and Web of Science (January 1, 2000-May 9, 2018) (eMethods 1 in the Supplement). We searched from 2000 because the PHQ-9 was published in 2001.5 We reviewed review articles and queried contributing authors about nonpublished studies or studies not identified by the search. We uploaded results into RefWorks (RefWorks-COS; Bethesda, Maryland), removed duplicates, then uploaded references into DistillerSR (Evidence Partners; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by varying pairs of 2 investigators. If 1 identified a study as potentially eligible, the full text was reviewed by pairs of 2 investigators independently. Any differences were resolved by consensus, with a third investigator consulted if necessary.

We conducted a literature search on April 6, 2020, to seek eligible published results that could be included. No studies published since the original search provided results for PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 combined.

Data Contribution, Extraction, and Synthesis

We emailed corresponding authors of studies with eligible data sets at least 3 times, as necessary, to invite them to contribute data sets. If there was no response, we emailed coauthors and attempted contact by telephone.

Country, recruitment setting (nonmedical, primary care, inpatient, outpatient specialty), and diagnostic interview were extracted from published reports by 2 investigators independently, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Countries were categorized as having very high, high, or low-medium development based on the United Nation’s 2019 Human Development Index.27 Individual participant records included sex, age, major depression status, current mental health diagnosis or treatment, and PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 total and item scores. PHQ-9 items reflect the 9 DSM symptoms of major depression; PHQ-2 items reflect depressed mood and anhedonia. We prioritized major depressive episode over major depressive disorder, if both were provided, because screening attempts to detect episodes, and we prioritized DSM over ICD. For 4 studies with multiple recruitment settings, setting was coded by participant. When primary studies provided sampling weights, we used those weights. If weighting should have been done but was not, we used inverse selection probability weights. If all study participants with scores above a threshold but only a random subset of 50% below the threshold received a diagnostic interview, for instance, those above the threshold received a weight of 1 and those below received a weight of 2.

For each included data set, we attempted to replicate published participant characteristics and accuracy results. We worked with primary study investigators to resolve any discrepancies.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias was assessed with the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies–2 tool (QUADAS-2; eMethods 2 in the Supplement).28 This was done by 2 investigators independently with discrepancies resolved by consensus, involving a third investigator, if necessary.

Statistical Analyses

The PHQ-2 score ranges from 0 to 6, and the PHQ-9 score ranges from 0 to 27. We estimated sensitivity and specificity for all possible PHQ-2 cutoffs (scores 1-6) by reference standard type separately: semistructured diagnostic interviews; fully structured diagnostic interviews, excluding the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)29,30; and the MINI. We did this because, controlling for depressive symptom scores, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),31 the most commonly used fully structured interview, may classify more participants with low-level symptoms as depressed, but fewer participants with higher-level symptoms, than semistructured interviews.11,12,13 The MINI may classify more participants as depressed.11,12,13 This is consistent with interview designs. Semistructured interviews are intended for administration by experienced diagnosticians, require clinical judgment, and allow question rephrasing and probes. Fully structured interviews are designed for lay interviewer administration and are fully scripted with no deviation allowed. They are intended to achieve standardization but may sacrifice accuracy.32,33,34,35 The MINI was designed for rapid administration and to be overinclusive.29,30

Within each reference standard category, we conducted subgroup analyses. We estimated sensitivity and specificity among participants who could be verified as not currently diagnosed or receiving mental health treatment vs all participants. This is because some primary studies included people already diagnosed or receiving treatment, but those participants would not be screened in practice. We estimated sensitivity and specificity by age (<60, ≥60 years), sex, country Human Development Index, and recruitment setting.

Among studies that used a semistructured interview, we evaluated accuracy of the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 combination based on commonly used cutoffs.8,20 We compared sensitivity and specificity for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater and 3 or greater alone and combined with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater vs PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater alone. In each scenario, we calculated the number of participants who scored above the PHQ-2 threshold and, in practice, would need to complete the full PHQ-9. For these analyses, we excluded studies and participants without PHQ-9 scores. In additional analyses, we compared sensitivity and specificity for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater in combination with PHQ-9 cutoff scores of 5 to 15 vs PHQ-9 alone at cutoff scores of 5 to 15.

In all meta-analyses, for all cutoff scores separately, we fit bivariate random-effects models using Gauss-Hermite quadrature.36 This 2-stage approach simultaneously models sensitivity and specificity, accounting for the correlation between them and within-study precision estimates. Within each reference standard category, we constructed empirical receiver operating characteristic plots and calculated area under the curve (AUC). To compare results between subgroups and for the PHQ-2 and PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 combination vs PHQ-9 alone, we estimated sensitivity and specificity differences and constructed confidence intervals for differences via the cluster bootstrap approach,37,38 resampling at study and participant levels. We ran 1000 bootstrap iterations for each comparison, omitting iterations where difference estimates were not produced. We considered differences to be statistically significantly different if their confidence intervals did not include 0.

To evaluate heterogeneity, for each included study, we produced sensitivity and specificity forest plots by reference standard category and for all studies in each subgroup within each category. We quantified heterogeneity by reporting τ2, the estimated variances of the random effects for sensitivity and specificity, and estimating R, the ratio of the estimated standard deviation of pooled sensitivity or specificity from the random-effects model to estimated standard deviation from the corresponding fixed-effects model.39

We generated hypothetical nomograms to illustrate possible positive and negative predictive values of PHQ-2 cutoff scores of 2 or greater and 3 or greater alone and in combination with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater for assumed major depression prevalence of 5% to 25%. These were based on summary sensitivity and specificity estimates from the analysis of studies that used semistructured interviews and had PHQ-9 scores available.

In sensitivity analyses, within each reference standard category, we evaluated whether there were accuracy differences by subgroups based on QUADAS-2 items. We did this for all items with at least 100 major depression cases and noncases rated as low vs unclear or high risk of bias.

For all analyses, we excluded studies with no major depression cases or noncases, because this did not allow application of the bivariate random-effects model, and participants missing data for a covariate of interest. There was a maximum of 74 participants excluded from any analysis. For clinical setting, we excluded 1 MINI study (130 participants) that recruited inpatients and outpatients but did not have participant-level setting data.

We did not conduct sensitivity analyses that combined accuracy results with published results from studies that did not contribute data. This is because, among 36 eligible studies that did not contribute data, only 2 studies with a semistructured reference standard40,41 (908 participants, 65 cases), 1 study with a fully structured reference standard42 (201 participants, 42 cases), and 4 studies using the MINI43,44,45,46 (878 participants, 220 cases) published accuracy results eligible for any analyses. The other studies with eligible data sets did not publish eligible accuracy results (eTable 1b in the Supplement).

All analyses were run in R (R version R 3.4.1 and R Studio version 1.0.143) using the glmer function within the lme4 package.47 For cutoff scores of 1 or greater for fully structured and 5 or greater for MINI reference standards, the default optimizer failed to converge, and bobyqa was used. In each analysis, pooled sensitivity and specificity and corresponding 2-sided 95% CIs were estimated.

Results

Search Results and Data Set Inclusion

The database search identified 9674 unique citations, of which 9198 were excluded after title and abstract review and 289 after full-text review, leaving 187 eligible articles with 131 unique data sets. Of these, 100 (76%) contributed data sets with PHQ-9 scores, PHQ-2 scores, or both. Authors of included studies contributed data from 5 additional unpublished studies, for a total of 105 data sets. Five data sets with PHQ-9 total scores did not have item data necessary to calculate PHQ-2 scores and were excluded. Thus, 100 data sets (44 318 participants; 4572 cases [10%]; mean [SD] age, 49 [17] years; 59% female) were included (Figure 1). eTable 1 in the Supplement shows study characteristics of included studies and eligible studies that did not provide data. Not counting the 5 unpublished studies, of 54 633 participants in 131 eligible published studies, we included 43 787 participants (80%) from 95 published studies (73%).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Selection Process.

MINI indicates Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Of the 100 included data sets, 48 were from studies that used semistructured interviews, 20 from studies that used fully structured interviews (MINI excluded), and 32 from studies that used the MINI. The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID)48 (45 studies, 9713 participants) and CIDI (17 studies, 15 899 participants) were the most commonly used semistructured and fully structured interviews (Table 2; eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Participant Data by Subgroup.

| Participant subgroup | Semistructured diagnostic interviews, No. (%) | Fully structured diagnostic interviews, No. (%) | MINI, No. (%)a | All interviews, No. (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Participants in category | Major depression | Studies | Participants in category | Major depression | Studies | Participants in category | Major depression | Studies | Participants in category | Major depression | |

| All participants | 48 | 11 703 (100) | 1538 (13) | 20 | 17 319 (100) | 1365 (8) | 32 | 15 296 (100) | 1669 (11) | 100 | 44 318 (100) | 4572 (10) |

| Subset of participants verified to not currently be diagnosed or receiving treatment for a mental health problemb | 25 | 3708 (32)c | 527 (14) | 5 | 4050 (23)c | 292 (7) | 15 | 8390 (55)c | 581 (7) | 45 | 16 148 (36)c | 1400 (9) |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||

| <60 | 46 | 7767 (67) | 1118 (14) | 20 | 13 901 (80) | 1097 (8) | 31 | 10 071 (66) | 1153 (11) | 97 | 31 739 (72) | 3368 (11) |

| ≥60 | 43 | 3888 (33) | 415 (11) | 16 | 3401 (20) | 268 (8) | 31 | 5219 (34) | 515 (10) | 90 | 12 508 (28) | 1198 (10) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Women | 48 | 7287 (62) | 1054 (14) | 20 | 9690 (56) | 802 (8) | 32 | 9057 (59) | 1138 (13) | 100 | 26 034 (59) | 2994 (12) |

| Men | 41 | 4408 (38) | 484 (11) | 18 | 7619 (44) | 561 (7) | 30 | 6233 (41) | 530 (9) | 89 | 18 260 (41) | 1575 (9) |

| Country Human Development Indexd | ||||||||||||

| Very high | 37 | 9156 (78) | 994 (11) | 16 | 15 574 (90) | 1162 (7) | 21 | 10 699 (70) | 1141 (11) | 74 | 35 429 (80) | 3297 (9) |

| High | 8 | 1957 (17) | 356 (18) | 9 | 4352 (28) | 433 (10) | 17 | 6309 (14) | 789 (13) | |||

| Low-medium | 3 | 590 (5) | 188 (32) | 4 | 1745 (10) | 203 (12) | 2 | 245 (2) | 95 (39) | 9 | 2580 (6) | 486 (19) |

| Recruitment setting | ||||||||||||

| Nonmedical caree | 2 | 567 (5) | 105 (19) | 4 | 8316 (48) | 378 (5) | 8 | 6792 (45) | 470 (7) | 14 | 15 675 (35) | 953 (6) |

| Primary care | 15 | 4569 (39) | 667 (15) | 7 | 4789 (28) | 429 (9) | 9 | 5092 (34) | 557 (11) | 31 | 14 450 (33) | 1653 (11) |

| Inpatient specialty care | 10 | 2019 (17) | 184 (9) | 2 | 593 (3) | 72 (12) | 4 | 619 (4) | 135 (22) | 16 | 3231 (7) | 391 (12) |

| Outpatient specialty care | 23 | 4548 (39) | 582 (13) | 7 | 3621 (21) | 486 (13) | 12 | 2663 (18) | 502 (19) | 42 | 10 832 (25) | 1570 (14) |

Abbreviation: MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

The MINI is a very brief fully structured diagnostic interview that was designed for rapid administration by lay interviewers and intended to be overinclusive.

This row contains the subset of participants that could be verified to not currently be diagnosed or receiving treatment for a mental health problem at the time of recruitment. Participants from studies that did not collect data on mental health diagnosis or treatment status were not included. Among studies that did collect this information, participants without a diagnosis or treatment were included, whereas those already diagnosed or receiving treatment were excluded.

Percentage refers to percentage of all participants within semistructured, fully structured, MINI, or all interviews who could be verified to not be currently diagnosed or receiving treatment.

Based on Human Development Report 2019.27 The Human Development Index is a composite index comprised of indicators of life expectancy, education, and per-capita income. In 2019, very-high human development countries include the top 59 countries; high included countries rated 60 to 112; medium, 113 to 151; and low, 152 to 189 (http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/HDI).

Nonmedical care recruitment included general community samples, as well as samples of older adults (2 studies), domestic workers (1 study), individuals in countries exposed to war (1 study), drug users (1 study), and employees on sickness leave (1 study).

PHQ-2 Sensitivity and Specificity

Among studies with a semistructured interview, sensitivity and specificity for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater were 0.91 (95% CI, 0.88-0.94) and 0.67 (95% CI, 0.64-0.71); for PHQ-2 scores of 3 or greater, sensitivity and specificity were 0.72 (95% CI, 0.67-0.77) and 0.85 (95% CI, 0.83-0.87), respectively. Across cutoffs, sensitivity with semistructured interviews was 0.04 (95% CI, 0.01-0.08) to 0.20 (95% CI, 0.10-0.28) higher than with fully structured interviews (significantly higher for cutoffs 1-6) and 0.02 (95% CI, 0.00-0.04) to 0.05 (95% CI, –0.04-0.13) higher than with the MINI (not significantly different at any cutoff); specificity was not significantly different across reference standard types (Table 3; eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The AUC was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.86-0.89) for semistructured interviews, 0.82 (95% CI, 0.81-0.84) for fully structured diagnostic interviews, and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.85-0.88) for the MINI.

Table 3. Comparison of PHQ-2 Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates Among Semistructured, Fully Structured, and MINI Reference Standards.

| Semistructured reference standard | Fully structured reference standard (MINI excluded) | MINIa reference standard | Differenceb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semistructured reference standard – fully structured reference standard | Semistructured reference standard – MINI reference standard | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 48 | 20 | 32 | |||||||

| No. of participants | 11 703 | 17 319 | 15 296 | |||||||

| No. of participants with major depression | 1538 | 1365 | 1669 | |||||||

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.89) | 0.82 (0.81 to 0.84) | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.88) | |||||||

| Cutoff score | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| 1 | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99) | 0.46 (0.42 to 0.51) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.96) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.58) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) | 0.48 (0.43 to 0.53) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.08) | –0.02 (–0.10 to 0.08) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | –0.01 (–0.07 to 0.04) |

| 2 | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) | 0.67 (0.64 to 0.71) | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.87) | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.77) | 0.89 (0.84 to 0.92) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.73) | 0.10 (0.03 to 0.18) | –0.03 (–0.09 to 0.04) | 0.02 (–0.02 to 0.09) | –0.01 (–0.06 to 0.04) |

| 3 | 0.72 (0.67 to 0.77) | 0.85 (0.83 to 0.87) | 0.53 (0.44 to 0.62) | 0.89 (0.84 to 0.92) | 0.69 (0.62 to 0.75) | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.90) | 0.19 (0.08 to 0.29) | –0.04 (–0.07 to 0.00) | 0.03 (–0.06 to 0.11) | –0.02 (–0.05 to 0.02) |

| 4 | 0.55 (0.50 to 0.61) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.94) | 0.36 (0.30 to 0.43) | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.96) | 0.50 (0.44 to 0.56) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.96) | 0.20 (0.10 to 0.28) | –0.01 (–0.03 to 0.01) | 0.05 (–0.04 to 0.13) | –0.01 (–0.03 to 0.01) |

| 5 | 0.35 (0.31 to 0.40) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 0.21 (0.16 to 0.26) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.30 (0.25 to 0.36) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.21) | –0.01 (–0.02 to 0.01) | 0.05 (–0.03 to 0.13) | –0.01 (–0.01 to 0.01) |

| 6 | 0.23 (0.19 to 0.27) | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.17) | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.18 (0.15 to 0.22) | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) | 0.10 (0.04 to 0.16) | 0.00 (–0.01 to 0.00) | 0.05 (–0.02 to 0.10) | 0.00 (–0.01 to 0.00) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PHQ-2, Patient Health Questionnaire–2.

The MINI is a very brief fully structured diagnostic interview that was designed for rapid administration by lay interviewers and intended to be overinclusive.

Because semistructured interviews are the type of diagnostic interview that most closely replicates diagnostic procedures, differences are not shown for fully structured reference standards – MINI reference standards.

There was moderate heterogeneity. For cutoffs 2 to 3, the τ2 values ranged from 0.47 to 1.29 for sensitivity and 0.27 to 0.78 for specificity, while R values ranged from 2.22 to 3.50 for sensitivity and 3.47 to 9.30 for specificity. Forest plots are shown in eFigure 2 and τ2 and R values in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Subgroup Analyses

Sensitivity and specificity estimates were not significantly different for participants verified as not currently diagnosed or receiving mental health treatment compared with all participants across reference standard categories. Among other subgroup comparisons, there were no statistically significant or substantive differences that replicated across cutoffs and reference standard categories (eTable 4; forest plots: eFigure 2; τ2 and R values: eTable 3 in the Supplement).

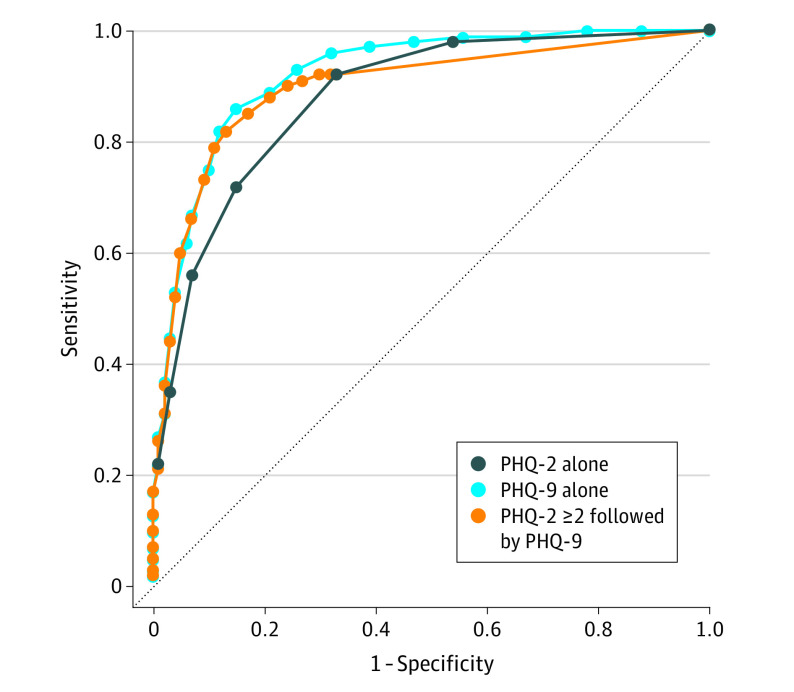

Comparison of PHQ-2, PHQ-2 in Combination With PHQ-9 ≥ 10, and PHQ-9 ≥ 10

Based on 44 studies that used a semistructured reference standard and provided both PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 scores, compared with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater alone, all strategies resulted in substantially reduced sensitivity or specificity, except PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater in combination with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater. For this combination, sensitivity was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.76-0.86) vs 0.86 (95% CI, 0.80-0.90) (not statistically significant) and specificity was slightly higher (0.87 [95% CI, 0.84-0.89] vs 0.85 [95% CI, 0.82-0.87]) (statistically significant; Table 4; eTable 5 in the Supplement; Figure 2). The AUC was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.89-0.91). Nomograms of positive and negative predictive values are shown in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. Using PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater in combination with other PHQ-9 cutoffs (5-9, 11-15) resulted in lower combined sensitivity and specificity compared with PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Comparison of Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates and Number of Participants Requiring Full PHQ-9 for PHQ-2 Alone, PHQ-2 in Combination With PHQ-9, and PHQ-9 Alone Among 44 Studies (No. of Participants = 10 627; No. of Participants With Major Depression = 1361) That Used a Semistructured Reference Standard and Had Both PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 Item Scores Availablea.

| Screening strategy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-2 score ≥2 alone | PHQ-2 score ≥3 alone | PHQ-2 score ≥2 then PHQ-9 score ≥10 | PHQ-2 score ≥3 then PHQ-9 score ≥10 | PHQ-9 score ≥10 alone | |

| PHQ-2 | |||||

| Administered, No. | 10 627 | 10 627 | 10 627 | 10 627 | |

| Positive screens, No. (%) | 4529 (42.6) | 2650 (24.9) | 4529 (42.6) | 2650 (24.9) | |

| PHQ-9 | |||||

| Administered, No. (%) | 4529 (42.6) | 2650 (24.9) | 10 627 (100.0) | ||

| Positive screens, No. (%) | 2461 (23.2) | 1946 (18.3) | 2655 (25.0) | ||

| Sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) | |||||

| Sensitivity | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.95) | 0.72 (0.67 to 0.77) | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.86) | 0.70 (0.64 to 0.75) | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.90) |

| Specificity | 0.67 (0.63 to 0.70) | 0.85 (0.83 to 0.87) | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.89) | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.93) | 0.85 (0.82 to 0.87) |

| Difference in accuracy estimates (each strategy – PHQ-9 alone) (95% CI) | |||||

| Sensitivity | 0.06 (0.01 to 0.11) | –0.13 (–0.20 to –0.09) | –0.04 (–0.09 to 0.01) | –0.16 (–0.23 to –0.12) | |

| Specificity | –0.18 (–0.21 to –0.16) | 0.01 (–0.02 to 0.03) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08) | |

Abbreviation: PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Among the 48 PHQ-2 studies that used a semistructured reference standard, 4 studies did not have PHQ-9 item scores available and thus could not be included in the comparison of screening strategies.

Figure 2. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Plots Comparing Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2) Alone, the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) Alone, and for PHQ-2 Scores of 2 or Greater Followed By PHQ-9.

The figure is for the 44 studies (participants = 10 627; No. with major depression = 1361) that used a semistructured reference standard and had both PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 item scores available. Among the 48 PHQ-2 studies that used a semistructured reference standard, 4 studies did not have PHQ-9 item scores available, and thus could not be included in the comparison of screening strategies. The PHQ-2 line has 7 calculated points (inflections), representing possible scores of 0 (right) to 6 (left). The PHQ-9 alone and PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater followed by PHQ-9 lines have 28 calculated points (inflections), representing possible scores of 0 (right) to 27 (left). The area under the curve was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.87-0.89) for PHQ-2 alone, 0.92 (95% CI, 0.91-0.93) for PHQ-9 alone, and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.89-0.91) for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater followed by PHQ-9.

With PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater then PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater, 43% (95% CI, 42%-44%) of participants had positive PHQ-2 screens and would have needed to complete the full PHQ-9 in practice; 23% (95% CI, 22%-24%) of all participants would have had a positive PHQ-9 screen and needed further mental health assessment compared with 25% (95% CI, 24%-26%) for PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater alone and 43% (95% CI, 42%-44%) for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater alone.

Risk of Bias Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 7 in the Supplement shows QUADAS-2 ratings for individual signaling items and risk of bias domains for included primary studies. Among 400 total domain ratings (4 per included study), 131 (33%) were coded as having low risk of bias, 253 (63%) as having an unclear risk, 11 (3%) as having a high risk, and 5 (1%) as varying across participants within a study. Three of 48 studies (6%) that used a semistructured interview, 6 of 20 studies (30%) with a fully structured interview, and 9 of 32 studies (28%) with a MINI reference standard had low risk of bias across all 4 domains.

PHQ-2 accuracy comparisons across QUADAS-2 items within reference standard categories are shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement. No statistically significant differences were found that replicated across cutoffs for any reference standard category.

Discussion

In this individual participant data meta-analysis of 44 studies that used semistructured diagnostic interviews to classify depression, sensitivity using the combination of PHQ-2 (cutoff ≥2) and PHQ-9 (cutoff ≥10) was not significantly different than using the full PHQ-9 (cutoff ≥10) for all participants. Specificity for the combination was significantly, though minimally, higher. The combination approach was estimated to reduce the number of participants needing to do the full PHQ-9 by 57% (95% CI, 56%-58%). Compared with the PHQ-9 alone, the PHQ-2 alone resulted in statistically significant lower sensitivity or specificity, depending on the cutoff score.

Consistent with previous findings with the PHQ-9,20 PHQ-2 sensitivity was highest compared with semistructured interviews, which most closely replicate clinical interviews by trained professionals, and lower compared with fully structured interviews and the MINI, although differences compared with the MINI were small and not statistically significant. Specificity estimates were not significantly different across reference standards. There were no significant accuracy differences between subgroups that replicated across reference standard categories, although some subgroups had limited numbers of participants and cases.

The finding that PHQ-2 sensitivity was greater when compared with semistructured rather than fully structured interviews may have occurred because fully structured interviews are designed for reliability at the cost of validity.32,33,34,35 Previous studies found that among participants with low-level depressive symptoms, fully structured interviews may classify more participants as having major depression than semistructured interviews but fewer among participants with high-level symptoms.11,12,13 In the present meta-analysis, most participants did not have major depression. Thus, misclassification of major depression among participants with subthreshold depressive symptoms based on fully structured interviews might explain the lower sensitivity compared with semistructured interviews.

Among studies with semistructured interviews, PHQ-2 sensitivity and specificity were generally similar to estimates reported in a previous aggregate-data meta-analysis that combined reference standards without adjustment.8 Using individual participant data from 48 studies with semistructured interviews in the present study, sensitivity and specificity were, respectively, 0.91 and 0.67 for cutoff scores of 2 or greater and 0.72 and 0.85 for cutoff scores of 3 or greater compared with 0.91 and 0.70 for cutoff scores of 2 or greater (17 studies) and 0.76 and 0.87 for cutoff scores of 3 or greater (19 studies) in the previous meta-analysis. This differed from a meta-analysis of PHQ-9 individual participant data,20 in which, among studies that used a semistructured interview, sensitivity at the standard cutoff score of 10 or greater was substantially greater than reported in a previous aggregate-data meta-analysis that combined reference standards.9,20

No previous meta-analysis and only 2 primary studies14,15 have evaluated the PHQ-2 in combination with the PHQ-9. The 2 primary studies, however, reported results using different cutoff combinations and generated estimates of sensitivity and specificity that differed among older community-dwelling adults (N = 378; sensitivity = 0.81, specificity = 0.89) and patients with coronary artery disease (N = 1024, sensitivity = 0.75, specificity = 0.84). Using individual participant data from 44 primary studies with semistructured interviews in the present study and standard cutoffs, which maximized combined sensitivity and specificity, sensitivity (0.82) for PHQ-2 scores of 2 or greater followed by PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater was not significantly different to PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater alone, and specificity (0.87) was significantly better, though minimally. Assuming that screening procedures allow for quick calculation of PHQ-2 scores before presenting remaining PHQ-9 items (eg, electronic administration), the combination could improve efficiency.

Routine screening for depression in primary care has been recommended in the United States.6 National guidelines from Canada and the United Kingdom, however, recommended against screening due to the lack of direct trial evidence of benefit and concerns about harms and consumption of health care resources.49,50,51,52 Well-conducted trials that compare screening vs no screening are needed to determine whether screening improves mental health outcomes. Using the PHQ-2 in combination with the PHQ-9 may be a resource-efficient approach. Many individuals who screen positive, however, will not meet major depression diagnostic criteria and will need to be evaluated by a clinician.

Strengths of the study included the large sample size, inclusion of results from all cutoffs from all studies (rather than just those published), assessment of PHQ-2 accuracy separately across reference standards and by participant subgroups, and evaluation of the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 combination, which had not been previously done in meta-analyses.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, primary data from 36 of 131 published eligible data sets (27%) were not included.

Second, there was moderate heterogeneity across studies, although it improved in most cases when subgroups were considered. Subgroup analyses based on medical comorbidities, as specified in the study protocol, and on country and language could not be conducted. This is because data on the presence of nonpsychiatric medical diagnoses were not available for 40% of participants, with higher percentages missing for specific diagnoses, and because many countries and languages were represented in few primary studies.

Third, many included studies did not explicitly exclude participants who may have already been diagnosed or receiving care for depression, although there were not statistically significant differences between analyses of participants verified to not currently be diagnosed or receiving treatment and analyses of all participants, including those without this information.

Fourth, studies in the meta-analysis of individual participant data were categorized based on the interview administered, but it is possible that interviews may not have always been used in the way intended. Among 48 studies that used semistructured interviews, 3 used interviewers who did not meet typical standards, and 11 were rated unclear. It is possible that use of nonqualified interviewers may have reduced differences in accuracy estimates across reference standard categories.

Fifth, few studies were rated as having a low risk of bias across all QUADAS-2 domains; thus, sensitivity analyses using only studies with all low ratings were not conducted.

Conclusions

In an individual participant data meta-analysis of studies that compared PHQ scores with major depression diagnoses, the combination of PHQ-2 (with cutoff ≥2) followed by PHQ-9 (with cutoff ≥10) had similar sensitivity but higher specificity compared with PHQ-9 cutoff scores of 10 or greater alone. Further research is needed to understand the clinical and research value of this combined approach to screening.

eMethods 1. Search Strategies

eMethods 2. Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) Coding Manual for Primary Studies Included in the Present Study

eFigure 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) Plots Comparing Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) Cutoffs 1-6 Among Semi-structured Diagnostic Interviews, Fully Structured Diagnostic Interviews, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

eFigure 2. Forest Plots of Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for Cutoff 2 and 3 of the PHQ-2 for Each Reference Standard Category, Including Among Participants Verified to Not Currently be Diagnosed or Receiving Treatment for a Mental Health Problem Compared to All Participants as Well as Among Participant Subgroups Based on Age, Sex, Human Development Index and Care Setting

eFigure 3. Nomograms of Positive and Negative Predictive Value for Assumed Major Depression Prevalence of 5-25%, Based on Accuracy Estimates Among Studies With a Semi-structured Reference Standard and PHQ-9 Scores Available

eTable 1. Characteristics of Included Primary Studies as Well as Eligible Primary Studies Not Included in the Present Study

eTable 2. Numbers of Participants and Cases of Major Depression by Diagnostic Interview

eTable 3. Estimates of Heterogeneity at PHQ-2 Cutoff Score of 2 and 3

eTable 4. Comparison of PHQ-2 Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates Among Participants Verified to Not Currently be Diagnosed or Receiving Treatment for a Mental Health Problem Compared to All Participants as Well as Among Participant Subgroups Based on Age, Sex, Human Development Index, Care Setting, and Risk of Bias Factors, for Each Reference Standard Category

eTable 5. Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for the PHQ-2 Alone, the PHQ-9 Alone, and for PHQ-2 ≥ 2 Followed by PHQ-9 Among 44 Studies (N Participants = 10,627; N Major Depression = 1,361) That Used a Semi-structured Reference Standard and Had Both PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 Item Scores Available

eTable 6. Comparison of Sensitivity and Specificity for PHQ-2 ≥ 2 in Combination With PHQ-9 ≥ 5 to 15 Versus Sensitivity and Specificity for PHQ-9 ≥ 5 to 15, Among Studies That Used a Semi-structured Diagnostic Interview as the Reference Standard

eTable 7. QUADAS-2 Ratings for Each Primary Study Included in the Present Study

References

- 1.Thombs BD, Ziegelstein RC. Does depression screening improve depression outcomes in primary care? BMJ. 2014;348:g1253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurer DM, Raymond TJ, Davis BN. Depression: screening and diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(8):508-515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Adult depression in primary care guideline. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Accessed April 7, 2020. https://pcptoolkit.beaconhealthoptions.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ICSI_Depression.pdf

- 4.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284-1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) . Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380-387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Family Physicians Clinical preventive service recommendation: depression. Accessed April 7, 2020. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/depression.html

- 8.Manea L, Gilbody S, Hewitt C, et al. Identifying depression with the PHQ-2. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:382-395. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moriarty AS, Gilbody S, McMillan D, Manea L. Screening and case finding for major depressive disorder using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):567-576. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. A diagnostic meta-analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) algorithm scoring method as a screen for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):67-75. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levis B, Benedetti A, Riehm KE, et al. Probability of major depression diagnostic classification using semi-structured versus fully structured diagnostic interviews. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(6):377-385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levis B, McMillan D, Sun Y, et al. Comparison of major depression diagnostic classification probability using the SCID, CIDI, and MINI diagnostic interviews among women in pregnancy or postpartum. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28(4):e1803. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Y, Levis B, Sun Y, et al. Probability of major depression diagnostic classification based on the SCID, CIDI and MINI diagnostic interviews controlling for Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Depression subscale scores. J Psychosom Res. 2020;129:109892. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson TM, He H, Podgorski C, Tu X, Conwell Y. Screening depression aging services clients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(12):1116-1123. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thombs BD, Ziegelstein RC, Whooley MA. Optimizing detection of major depression among patients with coronary artery disease using the patient health questionnaire. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2014-2017. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0802-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thombs BD, Benedetti A, Kloda LA, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for detecting major depression. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):124. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, et al. ; and the PRISMA-DTA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy studies. JAMA. 2018;319(4):388-396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, et al. ; PRISMA-IPD Development Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Individual Participant Data. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1657-1665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Y, Levis B, Riehm KE, et al. Equivalency of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9. Psychol Med. Published online July 12, 2019. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration . Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed, revised American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed, text revision American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization The ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thombs BD, Arthurs E, El-Baalbaki G, Meijer A, Ziegelstein RC, Steele RJ. Risk of bias from inclusion of patients who already have diagnosis of or are undergoing treatment for depression in diagnostic accuracy studies of screening tools for depression. BMJ. 2011;343:d4825. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Explanation and Elaboration (PRESS E&E). Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.United Nations Development Programme. Human development report 2019: beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today. Accessed April 7, 2020. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf

- 28.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. ; QUADAS-2 Group . QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529-536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): a short diagnostic structured interview. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):224-231. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):232-241. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83297-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1069-1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brugha TS, Jenkins R, Taub N, Meltzer H, Bebbington PE. A general population comparison of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) and the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN). Psychol Med. 2001;31(6):1001-1013. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R. A difference that matters: comparisons of structured and semi-structured psychiatric diagnostic interviews in the general population. Psychol Med. 1999;29(5):1013-1020. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799008880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nosen E, Woody SR. Diagnostic assessment in research In: McKay D, ed. Handbook of Research Methods in Abnormal and Clinical Psychology. Sage; 2008:chap 8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurdyak PA, Gnam WH. Small signal, big noise: performance of the CIDI depression module. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13):851-856. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley RD, Dodd SR, Craig JV, Thompson JR, Williamson PR. Meta-analysis of diagnostic test studies using individual patient data and aggregate data. Stat Med. 2008;27(29):6111-6136. doi: 10.1002/sim.3441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Leeden R, Busing FMTA, Meijer E. Bootstrap Methods for Two-Level Models: Technical Report PRM 97-04. Leiden University, Department of Psychology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Leeden R, Meijer E, Busing FMTA. Resampling multilevel models In: Leeuw J, Meijer E, eds. Handbook of Multilevel Analysis. Springer; 2008:401-433. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73186-5_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu ZW, Yu Y, Hu M, Liu HM, Zhou L, Xiao SY. PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 for screening depression in Chinese rural elderly. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phelan E, Williams B, Meeker K, et al. A study of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-9 in primary care elderly. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, Lu K, Li J, Sheng L, Ding R, Hu D. Value of Patient Health Questionnaires (PHQ)-9 and PHQ-2 for screening depression disorders in cardiovascular outpatients [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2015;43(5):428-431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi SK, Boyle E, Burchell AN, et al. ; OHTN Cohort Study Group . Validation of six short and ultra-short screening instruments for depression for people living with HIV in Ontario. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rathore JS, Jehi LE, Fan Y, et al. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression screening in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:215-220. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seo JG, Park SP. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and PHQ-2 in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2015;16(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0552-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong N, Fritzsche K, Wei J, et al. Validation of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for major depression in Chinese outpatients with multiple somatic symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:636-643. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bates D, Machler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1-48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID). John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thombs BD, Ziegelstein RC, Roseman M, Kloda LA, Ioannidis JP. There are no randomized controlled trials that support the United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline on screening for depression in primary care. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joffres M, Jaramillo A, Dickinson J, et al. ; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care . Recommendations on screening for depression in adults. CMAJ. 2013;185(9):775-782. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allaby M. Screening for Depression: A Report for the UK National Screening Committee (Revised Report). UK National Screening Committee; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Depression in adults: treatment and management: consultation draft. Accessed April 7, 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-cgwave0725/documents/full-guideline-updated [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Search Strategies

eMethods 2. Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) Coding Manual for Primary Studies Included in the Present Study

eFigure 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) Plots Comparing Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) Cutoffs 1-6 Among Semi-structured Diagnostic Interviews, Fully Structured Diagnostic Interviews, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

eFigure 2. Forest Plots of Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for Cutoff 2 and 3 of the PHQ-2 for Each Reference Standard Category, Including Among Participants Verified to Not Currently be Diagnosed or Receiving Treatment for a Mental Health Problem Compared to All Participants as Well as Among Participant Subgroups Based on Age, Sex, Human Development Index and Care Setting

eFigure 3. Nomograms of Positive and Negative Predictive Value for Assumed Major Depression Prevalence of 5-25%, Based on Accuracy Estimates Among Studies With a Semi-structured Reference Standard and PHQ-9 Scores Available

eTable 1. Characteristics of Included Primary Studies as Well as Eligible Primary Studies Not Included in the Present Study

eTable 2. Numbers of Participants and Cases of Major Depression by Diagnostic Interview

eTable 3. Estimates of Heterogeneity at PHQ-2 Cutoff Score of 2 and 3

eTable 4. Comparison of PHQ-2 Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates Among Participants Verified to Not Currently be Diagnosed or Receiving Treatment for a Mental Health Problem Compared to All Participants as Well as Among Participant Subgroups Based on Age, Sex, Human Development Index, Care Setting, and Risk of Bias Factors, for Each Reference Standard Category

eTable 5. Sensitivity and Specificity Estimates for the PHQ-2 Alone, the PHQ-9 Alone, and for PHQ-2 ≥ 2 Followed by PHQ-9 Among 44 Studies (N Participants = 10,627; N Major Depression = 1,361) That Used a Semi-structured Reference Standard and Had Both PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 Item Scores Available

eTable 6. Comparison of Sensitivity and Specificity for PHQ-2 ≥ 2 in Combination With PHQ-9 ≥ 5 to 15 Versus Sensitivity and Specificity for PHQ-9 ≥ 5 to 15, Among Studies That Used a Semi-structured Diagnostic Interview as the Reference Standard

eTable 7. QUADAS-2 Ratings for Each Primary Study Included in the Present Study