Abstract

Kynurenic acid, a metabolite of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan catabolism, acts as an antagonist for both the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and glycine coagonist sites of the N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor at endogenous brain concentrations. Elevation of brain kynurenic acid levels reduces the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and glutamate, and kynurenic acid is considered to be involved in psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and depression. Thus, the control of kynurenine pathway, especially kynurenic acid production, in the brain is an important target for the improvement of brain function or the effective treatment of brain disorders. Astrocytes uptake kynurenine, the immediate precursor of kynurenic acid, via large neutral amino acid transporters, and metabolize kynurenine to kynurenic acid by kynurenine aminotransferases. The former transport both branched-chain and aromatic amino acids, and the latter have substrate specificity for amino acids and their metabolites. Recent studies have suggested the possibility that amino acids may suppress kynurenic acid production via the blockade of kynurenine transport or via kynurenic acid synthesis reactions. This approach may be useful in the treatment and prevention of neurological and psychiatric diseases associated with elevated kynurenic acid levels.

Keywords: dopamine, kynurenic acid, kynurenine, large neutral amino acid transporter, neuropsychiatric disorders, neurotransmitter, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor, tryptophan

1. Introduction

The essential amino acid tryptophan is well known as a precursor of several bioactive compounds such as serotonin and melatonin. More than 90% of tryptophan is metabolized by the kynurenine pathway [1], and this pathway plays a critical role in tryptophan catabolism and coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) supply (Figure 1). Recently, many researchers have studied the kynurenine pathway, because the pathway has interesting intermediates and metabolites. For example, kynurenine regulates immunoreaction as an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist [2], and kynurenic acid (KYNA) affects brain function as an antagonist for both the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAchRs) and the N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor [3,4] and an agonist for the G protein-coupled receptor (GPR) 35 (GPR35) [5]. 3-hydroxykynurenine is a potential endogenous neurotoxin and oxidative stress generator [6], and quinolinic acid produces excitotoxicity as an NMDA receptor agonist [7]. Especially, KYNA function research has dramatically developed since 2001, and one of the targets for KYNA research is to manipulate KYNA production in the brain to prevent and improve psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and depression. In the present article, we briefly review recent advances in KYNA research and further describe the ability of amino acids to modulate KYNA production. The structure of tryptophan, kynurenine, and KYNA are shown in Figure 2.

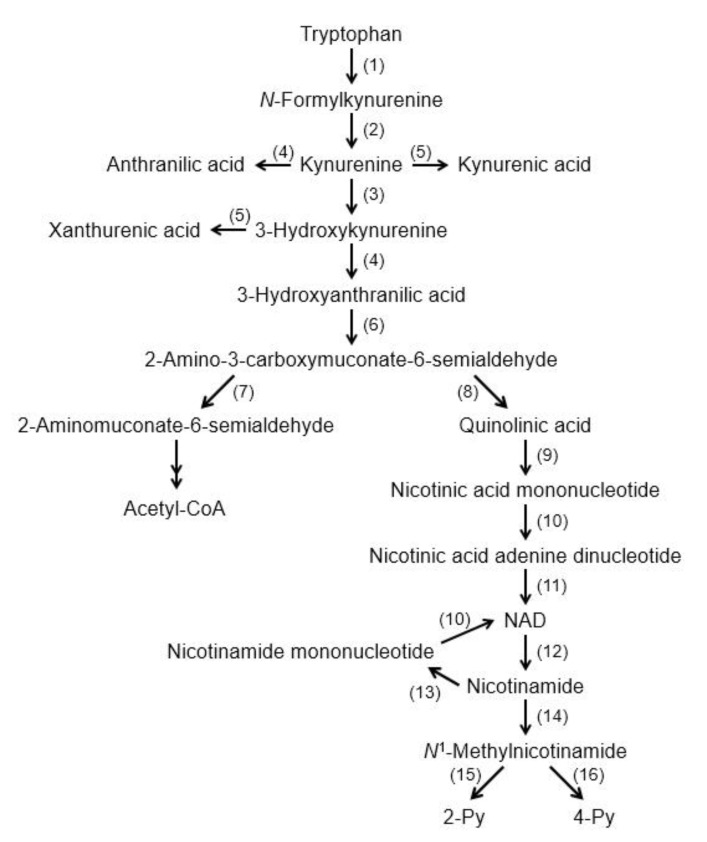

Figure 1.

Tryptophan degradation pathway. (1) Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase/Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (2) formamidase, (3) kynurenine 3-monoxygenase, (4) kynureninase, (5) kynurenine aminotransferase, (6) 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid oxygenase, (7) 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate-6-semialdehyde decarboxylase, (8) nonenzymatic reaction, (9) quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase, (10) nicotinic acid (nicotinamide) mononucleotide adenylyltransferase, (11) NAD+ synthetase, (12) NAD+ degrading enzyme, (13) nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, (14) nicotinamide methyltransferase, (15) 2-Py-forming N1-methylnicotinamide oxidase, and (16) 4-Py-forming N1-methylnicotinamide oxidase. Abbreviations: NAD+: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; 2 Py: N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide; and 4 Py: N1-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide.

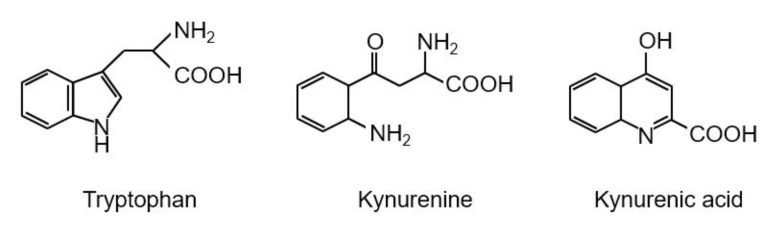

Figure 2.

Structures of tryptophan, kynurenine, and kynurenic acid.

2. Function of Kynurenic Acid in the Brain

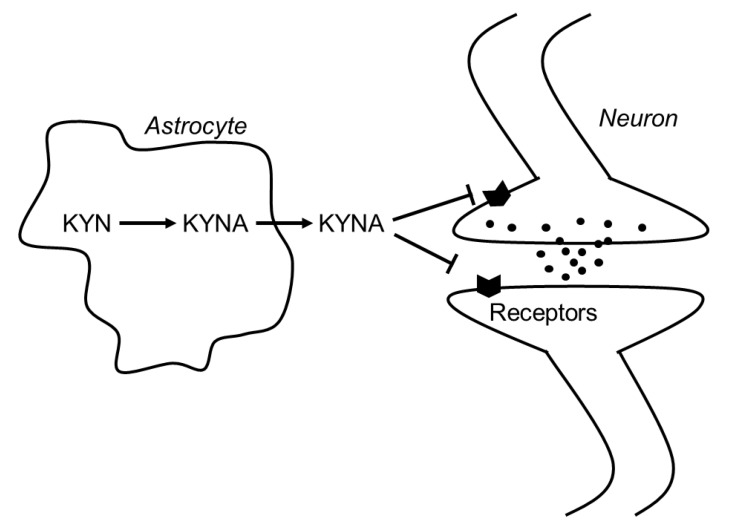

In 1989, Kessler et al. found that KYNA competitively inhibited glycine coagonist site of the NMDA receptor at low concentration with an IC50 of 8 μmol/L [3]. A decade later, Hilmas et al. found that KYNA noncompetitively inhibited α7nAchRs with an IC50 of 7 μmol/L using the patch-clamp technique with cultured hippocampal neurons [4]. Furthermore, Wang et al. found that KYNA is ligand for GPR35, whose EC50s are 10.7, 7.4, and 39.2 μmol/L in mouse, rat, and human, respectively [5]. Since physiological concentrations of brain KYNA are 5 pmol/g wet wt, 15 pmol/g wet wt, and 150 pmol/g wet wt in mouse, rat and human, respectively [8], elevation of brain KYNA has been considered to affect these receptors. Effects of KYNA increase on the neurotransmitter release were investigated using microdialysis technique, and KYNA concentration-dependently and reversibly reduced extracellular glutamate, dopamine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) to less than 50% of baseline concentrations [9,10,11]. Conversely, inhibition of endogenous KYNA formation by reverse dialysis of KYNA synthesis inhibitor (S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine (S-ESBA) reversibly increases dopamine, glutamate, and GABA levels in the rodent brain [11,12,13]. Although these findings suggest that changes of brain KYNA levels affect neurotransmitter release via modulation of above receptors, understanding the mechanism of action of KYNA is difficult. There is disagreement about the interaction between KYNA and α7nAchRs, because several studies failed to reproduce evidence for action of KYNA on nicotinic receptors. [14]. Schematic representation of the interaction between KYNA and the receptors is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the interaction between KYNA and neurotransmitters in the brain. Abbreviations: KYN: kynurenine; KYNA: kynurenic acid.

Behavioral studies showed that changes in brain KYNA levels affect several psychiatric functions in experimental animals. Elevation of endogenous KYNA concentration produces disruptions in prepulse inhibition [15] and habituation of auditory-evoked potentials [16], indicating that elevated KYNA levels interfere with normal reductions in processing and responding to irrelevant stimuli. Elevation of brain KYNA levels also affects cognitive function. For example, rats with elevations of endogenous KYNA exhibit spatial working memory deficits in a radial arm maze task [17]. These rats also exhibit impaired contextual fear memory consisting of two pairings of a tone and foot shock, and are slower to learn to discriminate between different contexts with or without foot shock [18]. On the other hand, reduction of endogenous KYNA levels by genetic and pharmacological manipulation improves cognitive functions. Mice with a targeted deletion of kynurenine aminotransferase II (KAT II), a major biosynthetic enzyme of brain KYNA, show reduced brain KYNA levels and significantly increased performance in three cognitive paradigms that rely in part on the integrity of hippocampal function, namely, object exploration and recognition, passive avoidance, and spatial discrimination [19]. Intracerebroventricular administration of selective KAT II inhibitor S-ESBA improves kynurenine-induced cognitive deficits on performance in the Morris water maze [20]. Systemic administration of KAT II inhibitor, PF-04859989, also dose-dependently reduces brain KYNA, prevents amphetamine- and ketamine-induced disruption of auditory gating, and improves performance in a sustained attention task [21]. It also prevents ketamine-induced disruption of performance in a working memory task and a spatial memory task in rodents and nonhuman primates, respectively. These findings support the hypotheses that endogenous KYNA impacts cognitive function and that inhibition of KAT II, and consequent lowering of endogenous brain KYNA levels, improves cognitive performance under conditions considered relevant for schizophrenia.

In humans, elevated KYNA levels are observed in the cerebrospinal fluid and cortex of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [22,23,24,25,26,27]. In the brain, kynurenine and KYNA levels in schizophrenic cases are 1.5 times higher than matched control subjects [24]. Similar observations reported that kynurenine and KYNA concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were 2 and 1.5 times higher in patients with schizophrenia, respectively, than with healthy volunteers, whereas tryptophan concentrations did not differ between the groups [26]. Patients with bipolar disorder have 1.5 times increased levels of KYNA in their CSF compared with healthy volunteers, and the levels of KYNA are positively correlated with age among bipolar patients but not in healthy volunteers [28]. Haplotype analysis shows an association between kynurenine 3-monoxygenase (KMO) gene polymorphisms and CSF concentrations of KYNA in patients with schizophrenia [29]. In the bipolar disorder and schizophrenia patients, KMO mRNA levels are reduced in the brain compared with nonpsychotic patients and controls, and the KMO Arg452 allele is associated with increased levels of CSF KYNA and reduced brain KMO expression [30]. KMO is the primary enzyme responsible for kynurenine degradation. These results support the hypothesis that KYNA is involved in the pathophysiology of psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

3. Kynurenic Acid Synthesis

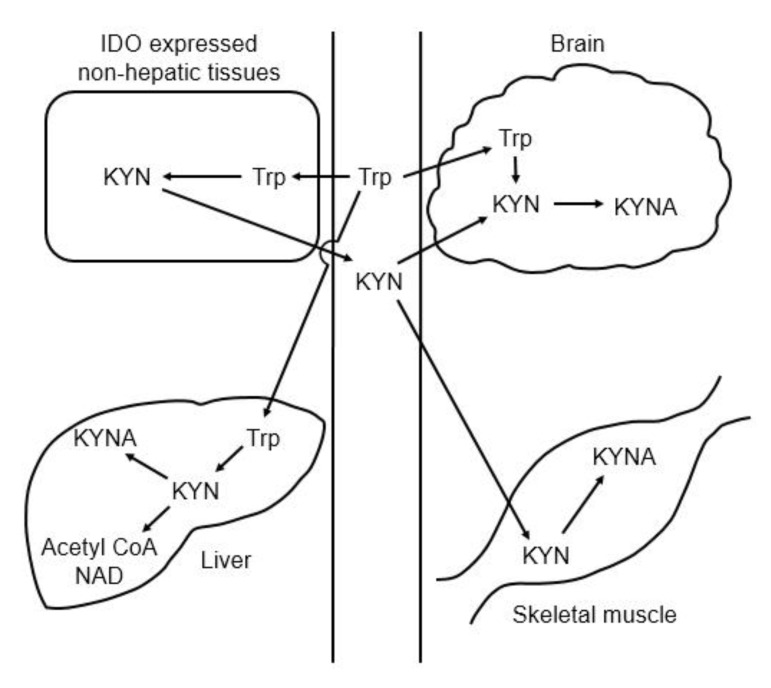

Tryptophan degradation is initiated by tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and these enzymes metabolize tryptophan to N-formylkynurenine, which is further degraded to kynurenine by formamidase. Kynurenine is catabolized to KYNA, 3-hydroxykynurenine, and anthranilic acid by KAT, KMO, and kynureninase, respectively. In the brain, 3-hyroxykynurenine and further downstream kynurenine pathway metabolites are synthesized in microglia, whereas KYNA is formed in astrocytes [31]. Approximately 40% of the kynurenine in brain is synthesized in astrocytes from tryptophan, and the remainder comes from plasma [32]. TDO-deficient mice show higher plasma tryptophan and kynurenine levels [33], and IDO-deficient mice show normal level of serum tryptophan and very low level of kynurenine [34]. These results suggest that most tryptophan is degraded by TDO in the liver, and that plasma kynurenine is derived from nonhepatic tissues and produced by IDO rather than TDO. Skeletal muscle also affects plasma kynurenine levels. Exercise training increases murine and human KAT expression in the skeletal muscle, and decreases plasma kynurenine levels by enhancement of kynurenine expenditure in the skeletal muscle [35]. Figure 4 shows the organ–organ interactions for tryptophan and kynurenine metabolism (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the organ–organ interaction for tryptophan and kynurenine metabolism. Abbreviations: IDO: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; KYN: kynurenine; KYNA: kynurenic acid; Trp: tryptophan.

Astrocytes uptake peripheral kynurenine from the blood stream via large neutral amino acid transporters (LATs). There is poor transport of KYNA across the blood–brain barrier, and for this reason plasma KYNA is not expected to contribute significantly to the brain KYNA pool [36]. LATs are known to transport both branched chain amino acids (e.g., valine, leucine, and isoleucine) and aromatic amino acids (e.g., tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan). Several findings show that LATs transport amino acids with higher affinity than kynurenine in tumor cell lines [36,37,38,39]. There are two LATs (LAT 1 and LAT 2); the affinity of LAT 1 to large neutral amino acids is higher than that of LAT 2. LAT 1 exhibits high-affinity transport of large neutral amino acids, including branched chain and aromatic amino acids, while LAT 2 transports not only large neutral amino acids but also small neutral amino acids in a fashion that appears to have broader substrate selectivity than LAT 1. [40,41]. LAT 1 is expressed in brain, spleen, placenta, testis, colon, and tumor cells, whereas LAT 2 is expressed at high levels in the small intestine, kidney, brain, and skeletal muscle. Neither of the LATs is expressed in the liver. The Km value of LATs for kynurenine is ~160 µmol/L, 80 times higher than plasma kynurenine concentrations [36,37], whereas the Km values of LAT 1 for leucine, isoleucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and histidine are 15–30 µmol/L, which are at physiological concentrations [39].

KATs catalyze the irreversible transamination reaction of kynurenine to KYNA. Four KATs have been identified in the mammalian brain: KAT I (glutamine transaminase K, GTK; EC 2.6.1.64), KAT II (2-aminoadipate aminotransferase, ADA; EC 2.6.1.7), KAT III (cysteine conjugate β-lyase 2, CCBL2; EC4.4.1.13), and KAT IV (mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase, ASAT; EC 2.6.1.1). The Km values of KAT I, II, III, and IV for kynurenine are 875 μmol/L, 660 μmol/L, 1.5 mmol/L and 724 μmol/L, respectively [42,43]. Specificity for substrates is different among KATs. KAT I is inhibited by glutamine (IC50: 0.2 mmol/L); KAT II by lysine metabolite 2-aminoadipic acid, quisqualate, aspartate, and glutamate (IC50: 0.006, 0.02, 1.2 and 2.1 mmol/L, respectively); KAT III by methionine, glutamine, histidine, and cysteine; and KAT IV by quisqualate, aspartate, glutamate, and 2-aminoadipic acid (IC50: 0.1, 0.3, 0.9 and 1.5 mmol/L, respectively) [42,43]. KAT II activity accounts for highest proportion (60%) of the total KAT activity in the rats and human brain, with 10 and 30% contributed by KAT I and IV, respectively. In mice brain, KAT IV is the dominant KAT with 60% of total KAT activity [42]. KAT III contribution to brain KYNA synthesis remains to be determined. These findings suggest that KAT II plays a central role for KYNA synthesis in the brain, and thus KAT II can be targeted to regulate KYNA production. KAT II-deficient mice exhibit lower KYNA levels in the brain and increased performance in cognitive functions [19,44]. KAT II inhibitors successfully prevent elevation of brain KYNA levels and cognitive dysfunction [20,21].

Several factors increase KYNA production in the brain in vivo. Systemic administration of kynurenine and KMO inhibitor increase brain KYNA levels by elevation of blood kynurenine levels [45,46]. Chronic exposure to a high-fat and low-protein/carbohydrate ketogenic diet shows a several-fold increase in KYNA concentrations in the rat striatum and hippocampus [47]. Experimental diabetes mellitus type 1 enhances KAT II activity and increases KYNA levels in the rat cortex and hippocampus [48]. Thioacetamide-induced acute liver failure enhances peripheral kynurenine production, and thus increases brain KYNA levels [49]. Acute stress increases brain KYNA levels in the fetus and adulthood [50,51,52], and reduction of stress-increased KYNA prevents the impairment of fear discrimination [52]. KMO gene polymorphisms influence CSF KYNA levels in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [29,30].

As the de novo synthesized KYNA immediately liberates to the extracellular compartment, extracellular KYNA levels are dependent on KYNA production, which is regulated by two key factors: KAT activity and the availability of the KYNA substrate kynurenine [53]. Kynurenine is produced in the peripheral tissues, and astrocytes uptake kynurenine from blood stream via LATs, catalyze kynurenine to KYNA via KATs, and then excrete KYNA to the extracellular compartment. Therefore, four points can affect brain KYNA levels: (1) kynurenine formation in the peripheral tissues, (2) kynurenine uptake by astrocytes, (3) KYNA synthesis by KATs, and (4) KYNA release from astrocytes. Enhancement of KAT II activity in the skeletal muscle by exercise is an example to modulate peripheral kynurenine formation [35]. Although organic anion transporters 1 and 3 transport KYNA, and both transporters express in the brain and kidney [54], little information is available for KYNA release from astrocytes. KYNA is also released from other KYNA-producing tissues, including the liver and skeletal muscle to blood stream, and then excreted to urine. The liver and skeletal muscle dominantly metabolize kynurenine to KYNA, and small amount of brain-derived KYNA contributes to plasma KYNA levels. Since elevated inflammatory activity may drive elevations of kynurenine and KYNA levels through the activation of IDO, peripheral KYNA measurements have been expected to be a predictor of central KYNA levels. However, studies of peripheral KYNA concentrations in psychiatric disorders have reported conflicting results [55,56,57]. Although enhancement of peripheral kynurenine production increases both peripheral and brain KYNA levels, that of brain kynurenine uptake and KATs activities does not always affect peripheral KYNA production.

4. Effects of Amino Acids on Kynurenic Acid Production

High tryptophan diets increase brain KYNA levels owing to increased peripheral kynurenine in a dose-dependent manner, and reduce dopamine release via enhancement of KYNA production in the rat striatum [58]. The plausible mechanism to increase brain KYNA levels is that the peripheral tissues produce more kynurenine from the high dose of tryptophan and release more kynurenine into the blood stream, and astrocytes take up the more circulating kynurenine and metabolize more kynurenine to KYNA by KATs. Chronic intake of 5 g/d of tryptophan shows two-fold of increase serum kynurenine concentration in healthy volunteers, suggesting increase of brain KYNA production due to excess tryptophan intake in humans [59].

As mentioned above, to modulate KYNA production in the brain, four points are relevant: (1) kynurenine formation in the peripheral tissues, (2) kynurenine uptake by astrocytes, (3) KYNA synthesis by KATs, and (4) KYNA release from astrocytes. Since LATs transport kynurenine and amino acids, including both branched chain and aromatic amino acids, and KATs have broad substrate specificity, including amino acids and its metabolites, amino acids have the potential to suppress KYNA production via inhibition of kynurenine uptake and KYNA synthesis in the brain. To this end, the effects of proteinogenic amino acids on KYNA formation and kynurenine uptake in rat brain in vitro were comprehensively investigated [60]. Ten out of 19 amino acids (specifically, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, methionine, tyrosine, alanine, cysteine, glutamine, glutamate, and aspartate) significantly reduce KYNA formation at 1 mmol/L in rat cortical slices. The amount of KYNA in the extracellular medium was reduced by 40–60% by eight amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, methionine, alanine, tyrosine, glutamine, glutamate, and aspartate), and by approximately 25% by phenylalanine and cysteine at 1 mmol/L. These amino acids show inhibitory effects in a dose-dependent manner, and partially inhibit KYNA production at physiological concentrations. Leucine, isoleucine, methionine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine, all LAT substrates, but not other five amino acids also reduce tissue kynurenine concentrations in a dose-dependent manner, and their inhibitory rates for kynurenine uptake significantly correlate with KYNA formation. IC50 for KYNA production and kynurenine uptake; Km values for LATs; and physiological concentration of amino acids, including LAT substrates, are shown in Table 1. The amino acids that inhibited KYN uptake are consistent with substrate amino acids of LAT 1 rather than LAT 2, suggesting a critical role of LAT 1 in kynurenine uptake in the brain. Km values of LAT 1 for leucine, isoleucine, methionine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine are 15–30 μmol/L, around physiological concentrations [38], indicating higher affinity than for kynurenine [39]. Furthermore, inhibition of LATs suppresses KYNA production via inhibition of kynurenine uptake in vitro and in vivo [61]. LATs inhibitor 2-aminobicyclo-(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH) inhibits KYNA production and kynurenine uptake in rat cortical slices in a dose-dependent manner. Administration of BCH suppresses kynurenine-induced elevations of kynurenine and KYNA levels to 50% and 70% in the mice brain. These results suggest that five LAT substrates inhibit KYNA formation via blockade of the KYN transport, while the other amino acids act via blockade of KYNA synthesis in the brain (Figure 5).

Table 1.

| IC50 (μmol/L) | Km (μmol/L) | Plasma Level (μmol/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KYNA Production | Kynurenine Uptake | hLAT1 | rLAT2 | ||

| Leucine | 36.9 | 30.4 | 19.7 | 119 | 153 |

| Phenylalanine | 22.5 | 10.4 | 14.2 | 45.0 | 58 |

| Isoleucine | 60.1 | 83.6 | 25.1 | 96.7 | 85 |

| Methionine | 184 | 98.6 | 20.2 | 204 | 54 |

| Tyrosine | 970 | 159 | 28.3 | 35.9 | 64 |

| Histidine | – | – | 12.7 | 181 | 69 |

| Valine | – | – | 47.2 | – | 194 |

| Glutamate | 94.9 | – | – | – | 77 |

| Cysteine | 110 | – | – | 109 | 11 |

| Alanine | 146 | – | – | 187 | 377 |

| Aspartate | 502 | – | – | 80.7 | 12 |

| Glutamine | 647 | – | 1640 | 151 | 711 |

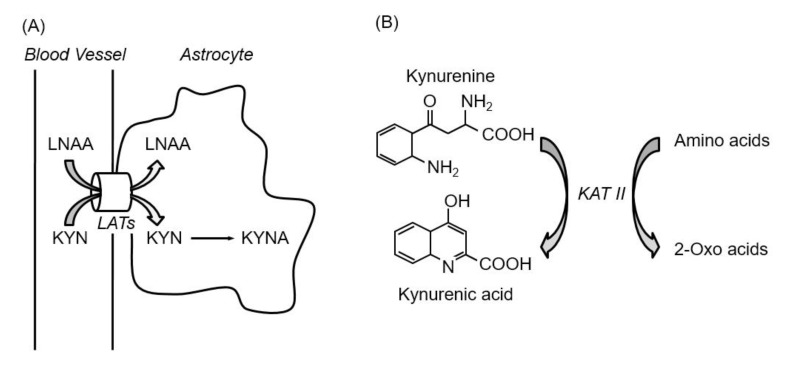

Figure 5.

Inhibition of kynurenine uptake via LATs by amino acids (A), and inhibition of kynurenic acid synthesis reaction by amino acids (B). Abbreviations: KAT II; kynurenine aminotransferase II, KYN; kynurenine, KYNA; kynurenic acid, LATs; large neutral amino acid transporters, LNAA; large neutral amino acids.

5. Conclusions

Recent studies have shown that KYNA modulates neurofunction by blockade of NMDA and α7nAch receptors, which is relevant to psychiatric disorders. Research has focused on pharmacologically manipulating KYNA formation to achieve the intended benefit and avoid harmful outcomes. Since humans intake several grams of amino acids from diet every day and amino acids are highly tolerable, chronic intake of amino acids may be a good tool to modulate brain function by manipulation of KYNA formation in the brain. This approach may be useful in the treatment and prevention of neurological and psychiatric diseases associated with elevated KYNA levels.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Dr. Katsumi Shibata, Emeritus Professor at The University of Shiga Prefecture for his advice and support to the research.

Funding

This study is supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research (KAKENHI) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT, Tokyo).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Keszthelyi D., Troost F.J., Masclee A.A. Understanding the role of tryptophan and serotonin metabolism in gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2009;21:1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opitz C.A., Litzenburger U.M., Sahm F., Ott M., Tritschler I., Trump S., Schumacher T., Jestaedt L., Schrenk D., Weller M., et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2011;478:197–203. doi: 10.1038/nature10491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler M., Terramani T., Lynch G., Baudry M. A glycine siteassociated with N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptors: Characterization and identification of a new class of antagonists. J. Neurochem. 1989;52:1319–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilmas C., Pereira E.F., Alkondon M., Rassoulpour A., Schwarcz R., Albuquerque E.X. The brain metabolite kynurenic acid inhibits α7 nicotinic receptor activity and increases non-α7 nicotinic receptor expression: Physiopathological implications. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7463–7473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07463.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J., Simonavicius N., Wu X., Swaminath G., Reagan J., Tian H., Ling L. Kynurenic acid as a ligand for orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR35. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:22021–22028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okuda S., Nishiyama N., Saito H., Katsuki H. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated neuronal cell death induced by an endogenous neurotoxin, 3-hydroxykynurenine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12553–12558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarcz R., Whetsell WOJr Mangano R.M. Quinolinic acid: An endogenous metabolite that causes axon-sparing lesions in rat brain. Science. 1983;219:316–318. doi: 10.1126/science.6849138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moroni F., Russi P., Lombardi G., Beni M., Carlà V. Presence of kynurenic acid in the mammalian brain. J. Neurochem. 1988;51:177–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb04852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenedo R., Pittaluga A., Cozzi A., Attucci S., Galli A., Raiteri M., Moroni F. Presynaptic kynurenate-sensitive receptors inhibit glutamate release. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:2141–2147. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rassoulpour A., Wu H.Q., Ferré S., Schwarcz R. Nanomolar concentrations of kynurenic acid reduce extracellular dopamine levels in the striatum. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:762–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beggiato S., Tanganelli S., Fuxe K., Antonelli T., Schwarcz R., Ferraro L. Endogenous kynurenic acid regulates extracellular GABA levels in the rat prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2014;82:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amori L., Wu H.Q., Marinozzi M., Pellicciari R., Guidetti P., Schwarcz R. Specific inhibition of kynurenate synthesis enhances extracellular dopamine levels in the rodent striatum. Neuroscience. 2009;159:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu H.Q., Pereira E.F., Bruno J.P., Pellicciari R., Albuquerque E.X., Schwarcz R. The astrocyte-derived α7 nicotinic receptor antagonist kynurenic acid controls extracellular glutamate levels in the prefrontal cortex. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2010;40:204–210. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone T.W. Does kynurenic acid act on nicotinic receptors? An assessment of the evidence. J. Neurochem. 2020;152:627–649. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erhardt S., Schwieler L., Emanuelsson C., Geyer M. Endogenous kynurenic acid disrupts prepulse inhibition. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;56:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shepard P.D., Joy B., Clerkin L., Schwarcz R. Micromolar brain levels of kynurenic acid are associated with a disruption of auditory sensory gating in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1454–1462. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chess A.C., Simoni M.K., Alling T.E., Bucci D.J. Elevations of endogenous kynurenic acid produce spatial working memory deficits. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:797–804. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chess A.C., Landers A.M., Bucci D.J. l-Kynurenine treatment alters contextual fear conditioning and context discrimination but not cue-specific fear conditioning. Behav. Brain Res. 2009;201:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potter M.C., Elmer G.I., Bergeron R., Albuquerque E.X., Guidetti P., Wu H.Q., Schwarcz R. Reduction of endogenous kynurenic acid formation enhances extracellular glutamate, hippocampal plasticity, and cognitive behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1734–1742. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocivavsek A., Wu H.Q., Potter M.C., Elmer G.I., Pellicciari R., Schwarcz R. Fluctuations in endogenous kynurenic acid control hippocampal glutamate and memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2357–2367. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozak R., Campbell B.M., Strick C.A., Horner W., Hoffmann W.E., Kiss T., Chapin D.S., McGinnis D., Abbott A.L., Roberts B.M., et al. Reduction of brain kynurenic Acid improves cognitive function. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:10592–10602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1107-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinrichs R.W., Zakzanis K.K. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–445. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erhardt S., Blennow K., Nordin C., Skogh E., Lindstrom L.H., Engberg G. Kynurenic acid levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with schizophrenia. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;313:96–98. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02242-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarcz R., Rassoulpour A., Wu H.Q., Medoff D., Tamminga C.A., Roberts R.C. Increased cortical kynurenate content in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2001;50:521–530. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sathyasaikumar K.V., Stachowski E.K., Wonodi I., Roberts R.C., Rassoulpour A., McMahon R.P., Schwarcz R. Impaired kynurenine pathway metabolism in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37:1147–1156. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linderholm K.R., Skogh E., Olsson S.K., Dahl M.L., Holtze M., Engberg G., Samuelsson M., Erhardt S. Increased levels of kynurenine and kynurenic acid in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38:426–432. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kindler J., Lim C.K., Weickert C.S., Boerrigter D., Galletly C., Liu D., Jacobs K.R., Balzan R., Bruggemann J., O’Donnell M., et al. Dysregulation of kynurenine metabolism is related to proinflammatory cytokines, attention, and prefrontal cortex volume in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsson S.K., Samuelsson M., Saetre P., Lindström L., Jönsson E.G., Nordin C., Engberg G., Erhardt S., Landén M. Elevated levels of kynurenic acid in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with bipolar disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35:195–199. doi: 10.1503/jpn.090180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holtze M., Saetre P., Engberg G., Schwieler L., Werge T., Andreassen O.A., Hall H., Terenius L., Agartz I., Jönsson E.G., et al. Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase polymorphisms: Relevance for kynurenic acid synthesis in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:53–57. doi: 10.1503/jpn.100175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavebratt C., Olsson S., Backlund L., Frisén L., Sellgren C., Priebe L., Nikamo P., Träskman-Bendz L., Cichon S., Vawter M.P., et al. The KMO allele encoding Arg452 is associated with psychotic features in bipolar disorder type 1, and with increased CSF KYNA level and reduced KMO expression. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:334–341. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guillemin G.J., Kerr S.J., Smythe G.A., Smith D.G., Kapoor V., Armati P.J., Croitoru J., Brew B.J. Kynurenine pathway metabolism in human astrocytes: A paradox for neuronal protection. J. Neurochem. 2001;78:842–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gál E.M., Sherman A.D. l-Kynurenine: Its synthesis and possible regulatory function in brain. Neurochem. Res. 1980;5:223–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00964611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanai M., Funakoshi H., Takahashi H., Hayakawa T., Mizuno S., Matsumoto K., Nakamura T. Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase is a key modulator of physiological neurogenesis and anxiety-related behavior in mice. Mol. Brain. 2009;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanz T.V., Williams S.K., Stojic A., Iwantscheff S., Sonner J.K., Grabitz C., Becker S., Böhler L.I., Mohapatra S.R., Sahm F., et al. Tryptophan-2,3-Dioxygenase (TDO) deficiency is associated with subclinical neuroprotection in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41271. doi: 10.1038/srep41271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agudelo L.Z., Femenía T., Orhan F., Porsmyr-Palmertz M., Goiny M., Martinez-Redondo V., Correia J.C., Izadi M., Bhat M., Schuppe-Koistinen I., et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1α1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress-induced depression. Cell. 2014;159:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukui S., Schwarcz R., Rapoport S.I., Takada Y., Smith Q.R. Blood-brain barrier transport of kynurenines: Implications for brain synthesis and metabolism. J. Neurochem. 1991;56:2007–2017. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb03460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Speciale C., Hares K., Schwarcz R., Brookes N. High-affinity uptake of l-kynurenine by a Na+-independent transporter of neutral amino acids in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:2066–2072. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-02066.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanagida O., Kanai Y., Chairoungdua A., Kim D.K., Segawa H., Nii T., Cha S.H., Matsuo H., Fukushima J., Fukasawa Y., et al. Human L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1): Characterization of function and expression in tumor cell lines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1514:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asai Y., Bajotto G., Yoshizato H., Hamada K., Higuchi T., Shimomura Y. The effects of endotoxin on plasma free amino acid concentrations in rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitam. 2008;54:460–466. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.54.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanai Y., Segawa H., Miyamoto Ki Uchino H., Takeda E., Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transport for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23629–23632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segawa H., Fukasawa Y., Miyamoto K., Takeda E., Endou H., Kanai Y. Identification and functional characterization of a Na+-independent neutral amino acid transporter with broad substrate selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19745–19751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guidetti P., Amori L., Sapko M.T., Okuno E., Schwarcz R. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase: A third kynurenate-producing in the mammalian brain. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han Q., Robinson H., Cai T., Tagle D.A., Li J. Biochemical and structural properties of mouse kynurenine aminotransferase III. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:784–793. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01272-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alkondon M., Pereira E.F., Yu P., Arruda E.Z., Almeida L.E., Guidetti P., Fawcett W.P., Sapko M.T., Randall W.R., Schwarcz R., et al. Targeted deletion of the kynurenine aminotransferase ii gene reveals a critical role of endogenous kynurenic acid in the regulation of synaptic transmission via alpha7 nicotinic receptors in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4635–4648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5631-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swartz K.J., During M.J., Freese A., Beal M.F. Cerebral synthesis and release of kynurenic acid: An endogenous antagonist of excitatory amino acid receptors. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:2965–2973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-09-02965.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Röver S., Cesura A.M., Huguenin P., Kettler R., Szente A. Synthesis and biochemical evaluation of N-(4-phenylthiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamides as high-affinity inhibitors of kynurenine 3-hydroxylase. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:4378–4385. doi: 10.1021/jm970467t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Żarnowski T., Chorągiewicz T., Tulidowicz-Bielak M., Thaler S., Rejdak R., Żarnowski I., Turski W.A., Gasior M. Ketogenic diet increases concentrations of kynurenic acid in discrete brain structures of young and adult rats. J. Neural. Transm. 2012;119:679–684. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chmiel-Perzyńska I., Perzyński A., Urbańska E.M. Experimental diabetes mellitus type 1 increases hippocampal content of kynurenic acid in rats. Pharm. Rep. 2014;66:1134–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sekine A., Fukuwatari T. Acute liver failure increases kynurenic acid production in rat brain via changes in tryptophan metabolism in the periphery. Neurosci. Lett. 2019;701:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pawlak D., Takada Y., Urano T., Takada A. Serotonergic and kynurenic pathways in rats exposed to foot shock. Brain Res. Bull. 2000;52:197–205. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(00)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Notarangelo F.M., Schwarcz R. Restraint stress during pregnancy rapidly raises kynurenic acid levels in mouse placenta and fetal brain. Dev. Neurosci. 2016;38:458–468. doi: 10.1159/000455228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klausing A.D., Fukuwatari T., Bucci D.J., Schwarcz R. Stress-induced impairment in fear discrimination is causally related to increased kynurenic acid formation in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00213-020-05507-x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turski W.A., Gramsbergen J.B., Trailer H., Schwarcz R. Rat brain slices produce and liberate kynurenic acid upon exposure to l-kynurenine. J. Neurochem. 1989;52:1629–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uwai Y., Honjo H., Iwamoto K. Interaction and transport of kynurenic acid via human organic anion transporters hOAT1 and hOAT3. Pharm. Res. 2012;65:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravikumar A., Deepadevi K.V., Arun P., Manojkumar V., Kurup P.A. Tryptophan and tyrosine catabolic pattern in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurol. India. 2000;48:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plitman E., Iwata Y., Caravaggio F., Nakajima S., Chung J.K., Gerretsen P., Kim J., Takeuchi H., Chakravarty M.M., Remington G., et al. Kynurenic Acid in Schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:764–777. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wurfel B.E., Drevets W.C., Bliss S.A., McMillin J.R., Suzuki H., Ford B.N., Morris H.M., Teague T.K., Dantzer R., Savitz J.B. Serum kynurenic acid is reduced in affective psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1115. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okuno A., Fukuwatari T., Shibata K. High tryptophan diet reduces extracellular dopamine release via kynurenic acid production in rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 2011;118:796–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hiratsuka C., Fukuwatari T., Sano M., Saito K., Sasaki S., Shibata K. Supplementing healthy women with up to 5.0 g/d of l-tryptophan has no adverse effects. J. Nutr. 2013;143:859–866. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.173823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sekine A., Okamoto M., Kanatani Y., Sano M., Shibata K., Fukuwatari T. Amino acids inhibit kynurenic acid formation via suppression of kynurenine uptake or kynurenic acid synthesis in rat brain in vitro. Springerplus. 2015;4:48. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-0826-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sekine A., Kuroki Y., Urata T., Mori N., Fukuwatari T. Inhibition of large neutral amino acid transporters suppresses kynurenic acid production via inhibition of kynurenine uptake in rodent brain. Neurochem. Res. 2016;41:2256–2266. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1940-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]