Abstract

Mitochondrial genes in flowering plants contain predominantly group II introns that require precise splicing before translation into functional proteins. Splicing of these introns is facilitated by various nucleus-encoded splicing factors. Due to lethality of mutants, functions of many splicing factors have not been revealed. Here, we report the function of two P-type PPR proteins PPR101 and PPR231, and their role in maize seed development. PPR101 and PPR231 are targeted to mitochondria. Null mutation of PPR101 and PPR231 arrests embryo and endosperm development, generating empty pericarp and small kernel phenotype, respectively, in maize. Loss-of-function in PPR101 abolishes the splicing of nad5 intron 2, and reduces the splicing of nad5 intron 1. Loss-of-function in PPR231 reduces the splicing of nad5 introns 1, 2, 3 and nad2 intron 3. The absence of Nad5 protein eliminates assembly of complex I, and activates the expression of alternative oxidase AOX2. These results indicate that both PPR101 and PPR231 are required for mitochondrial nad5 introns 1 and 2 splicing, while PPR231 is also required for nad5 intron 3 and nad2 intron 3. Both genes are essential to complex I assembly, mitochondrial function, and maize seed development. This work reveals that the splicing of a single intron involves multiple PPRs.

Keywords: PPR proteins, group II intron splicing, nad5, complex I biogenesis, mitochondria, maize seed development

Introduction

Mitochondria are highly metabolically active organelles in eukaryotic cells that perform multiple cellular functions, including basic energy supply and redox regulation, ion transmembrane transport, and metabolic pathways integration (Sweetlove et al., 2007). Mitochondria are derived from ancient α-proteobacteria via endosymbiosis and the majority of bacterial genes are either transferred to the host nuclear genome or lost during evolution (Martin and Herrmann, 1998). The present mitochondria in higher plants host only 5% of the genes encoding proteins essential for mitochondrial biogenesis and functions (Gray et al., 1999; Martin et al., 2012). For example, the maize mitochondrial genome contains 58 genes encoding 22 proteins for respiratory chain, 9 ribosomal proteins (RP), a transporter (MttB), a maturase (Mat-r), 3 rRNAs (rrn5, rrn18, rrn26), and 21 tRNAs (for 14 amino acids) (Clifton et al., 2004). Moreover, expression of the mitochondrial genes is strictly regulated by the nuclear genome, particularly at post-transcriptional level which includes intron splicing, RNA editing, RNA cleavage, RNA stabilization and translation (Fujii and Small, 2011; Barkan and Small, 2014).

Except for cox1 that contains a group I intron in some angiosperm species, most of the mitochondrial genes in flowering plants only contain group II introns (Brown et al., 2014). Most of them are cis-spliced introns that the splicing occurs in one mRNA molecule. Some group II introns, however, are fragmented and transcribed as separate RNAs, which are spliced in trans configuration (Bonen, 2008; Brown et al., 2014). Group II introns typically consist of six stem-loops, DI-DVI, of which DI, DV, and DVI are crucial to intron splicing (Novikova and Belfort, 2017). Typical group II introns are also mobile genetic elements which can reversely transcribe and insert back into the host genome, referred as “retrohoming” (Eickbush, 1999). Bacterial group II introns can self-splice under high-salt concentrations in vitro, but in vivo the splicing is facilitated by the cognate intron-encoded maturase (Mat) (Pyle, 2016). Higher plant organellar introns, however, have lost the self-splicing capability due to mutations in intron sequences, rearrangement, and loss of most maturase genes during evolution (Schmitz-Linneweber et al., 2015). In addition, most intron specific maturase genes have been lost, with only a matK gene retained in the trnK intron in plastids and a matR gene retained in the 4th intron of nad1 in mitochondria (Clifton et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2014). For these reasons, intron splicing in higher plant organelles requires a large number of nuclear-encoded RNA-binding factors in addition to the maturases. Recent studies have indicated that multiple families of RNA binding proteins are involved in intron splicing. In plant organelles, these include plant organellar RNA recognition (PORR) protein (Kroeger et al., 2009; Francs-Small et al., 2012), DEAD-box RNA helicase (Köhler et al., 2010), regulator of chromosome condensation-like (RCC) protein (Kühn et al., 2011), RAD-52-like protein (Samach et al., 2011), chloroplast RNA splicing and ribosome maturation (CRM) proteins (Zmudjak et al., 2013), mitochondrial transcription termination factor (mTERF) proteins (Hammani and Barkan, 2014) and pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins (Barkan and Small, 2014).

PPRs are a large family of nuclear-encoded proteins widespread in land plants, with 400 to 600 PPR genes in most angiosperm genomes (Lurin et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2016). PPRs consist of 2 to 30 tandem repeats of a degenerate 35-amino-acid motif that forms an anti-parallel α- helix (Yin et al., 2013). Based on their constituent motifs, PPRs are divided into P-type and PLS-type subfamilies. The P-type subfamily contains only P motifs, and PLS-type subfamily contains long (L, 35 or 36 amino acids) and short (S, 31 amino acids) motifs. Based on the C terminal domain, PLS-type subfamily is further classified into E, E+, and DYW subgroups (Claire et al., 2004). PLS-type PPR proteins are predominantly involved in RNA editing (Liu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014, 2019; Sun et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017), whereas P-type PPR proteins participate in intron splicing (Liu et al., 2010; Hsieh et al., 2015; Xiu et al., 2016; Ren et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019), RNA stability (Haili et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017), and translation (Cohen et al., 2014; Haili et al., 2016).

In plants, most of mitochondrial introns reside in nad (NADH dehydrogenase) genes, which encode subunits of complex I in mitochondrial respiratory chain (Li-Pook-Than and Bonen, 2006). Maize mitochondrial genome contains 22 group II introns, of which 19 reside in nad genes, nad1, nad2, nad4, nad5 and nad7, and 3 in rps3, cox2, and ccmFc genes. And five of them are trans introns (Burger et al., 2003; Clifton et al., 2004). Previous studies have reported the P-type PPRs participating in intron splicing of mitochondrial nad genes. In Arabidopsis, OTP43 is required for the splicing of nad1 intron 1 and nad2 intron 1 (De Longevialle et al., 2007), ABO5 and MISF26 for nad2 intron 3 (Liu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2018), OTP439 for nad5 intron 2 and TANG2 for nad5 intron 3 (Francs-Small et al., 2012), BIR6 for nad7 intron1 and SLO3 for nad7 intron 2 (Koprivova et al., 2010; Hsieh et al., 2015). In maize, EMP11 and DEK2 are involved in nad1 introns splicing (Qi et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017). EMP16, EMP10, DEK37 and EMP12 are required for nad2 introns splicing (Xiu et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2017; Dai et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019). DEK35, DEK41, DEK43, and EMP602 are implicated in nad4 introns splicing (Chen et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2019, 2020; Zhu et al., 2019). The loss-of-function in these PPRs gives rise to splicing deficiency, and impedes the assembly and activity of complex I, thus disrupting the function of mitochondrial respiratory chain. These results imply the essential effects of PPRs on intron splicing and mitochondrial metabolism. However, the unknown molecular function of a large number of PPRs and the mechanism of intron splicing still need more research.

In this study, we reveal the function of two P-type PPR proteins on the splicing of multiple nad5 introns through a genetic and molecular characterization of ppr101 and ppr231 mutants. Interestingly, both PPR101 and PPR231 are required for the splicing of nad5 introns 1 and 2, suggesting that splicing of a single intron requires more than one PPR proteins. These two proteins may not interact physically. We further prove that PPR101 and PPR231 are essential to mitochondrial complex I biogenesis and seed development in maize. This work adds to body of information on PPR functions and provides clue to the elucidation of intron splicing in mitochondria.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

The two alleles of the ppr101 and ppr231 mutants were isolated from the UniformMu stocks (Mccarty et al., 2013) and backcrossed to the W22 inbred genetic background. The mutator insertion was confirmed by PCR amplification using gene-specific primers and Mu-specific primers. The mutants were kept in heterozygotes condition and maize plants were grown in the experimental field in Qingdao, Shandong Province and Huangliu, Hainan Province under natural growth conditions.

DNA Extraction and Linkage Analysis

Genomic DNA of young maize leaf was extracted by urea-phenol-chloroform-based extraction method as described previously (Tan et al., 2011). For linkage analysis experiment, the leaf genomic DNA was extracted from individual plant and used as templates for PCR analysis. Each plant was self-pollinated and the progeny was observed for segregation of mutant kernels at 25% ratio.

Light Microscopy of Cytological Sections

Wildtype and mutant kernels were obtained from heterozygous maize plants which were self-pollinated at 9 DAP and 15 DAP. The fixed kernels were sectioned after dehydrated, infiltrated, embedded, de-paraffinized and stained as described previously (Shen et al., 2013).

Subcellular Localization of PPR101 and PPR231

The first 400-bp fragment of PPR101 and 615-bp of PPR231 in coding region without the stop codon were amplified from maize cDNA of the W22 inbred line. PCR products were cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and then integrated into binary vector pGWB5 by LR site-specific recombination. The destination plasmid pGWB5-PPR101N200-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (pGWB5-PPR101N200-GFP) and pGWB5-PPR231N205-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (pGWB5-PPR231N205-GFP) were then introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 and infiltrated into Nicotiana tabacum leaf epidermal cells as described (Herpen et al., 2010). The co-localization of GFP signal and MitoTracker Red were observed after 24–36 h with an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope. MitoTracker Red (Thermofisher Scientific)1 was used as the mitochondrion maker.

RNA Extraction, RT-PCR and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIANGE)2 from 100 mg of kernels samples according to the protocol. RNA was further treated with RNase-free DNase I (ThermoFisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, United States) to remove residual DNA contamination. The reverse transcription PCR was performed according to the TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TRANSGEN BIOTECH) instructions. Expression level of PPR101 and PPR231 in the WT and different alleles was analyzed by primers PPR101-F1/R1 and PPR231-F1/R1. ZmActin (GRMZM2G126010) was used as normalization. Expression pattern of PPR101 and PPR231 in various maize tissues was analyzed by qRT-PCR using primers PPR101-RT-F1/R1 and PPR231-RT-F1/R1. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay was performed with SYBR Green according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Bio-Rad)3. cDNA was synthesized using 500 ng total RNA in a 25 μl reaction and then diluted 10 times. After normalization against ZmActin to account for RT efficiency differences, roughly 2 ng RNA (derived cDNA) was used as a template in a 15 μl reaction for qRT-PCR amplification in a Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch Light Cycler. The relative quantification of gene expression was calculated by the 2–ΔΔCt method. ZmActin (GRMZM2G126010) reference gene was used to normalize the expression. For each qRT-PCR experiment, three biological replicates and three technical replicates were analyzed. The primers were used as described (Li et al., 2014). Additional primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Functional Analysis of PPR101 and PPR231

Total RNA was extracted from embryos and endosperms of the wildtype, ppr101 and ppr231 mutant kernels at 12 DAP and gDNA removal was carried out as described above. RNA without gDNA contamination was reverse transcribed with random hexamers. The expression level of 35 maize mitochondrial transcripts in the WT, ppr101 and ppr231 mutants was analyzed by RT-PCR with primers as described previously (Liu et al., 2013). The splicing efficiency of 22 mitochondrial group II introns between the WT, ppr101 and ppr231 mutants was compared by RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. ZmActin was used as normalization. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

BN-PAGE, Mitochondrial Complex I Activity and Western Blotting

Crude mitochondria of the embryo and endosperm from 9 to 14 DAP of the wildtype and mutant kernels were extracted as described (Li et al., 2014). Blue native-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and in-gel complex I activity assay were carried out as described previously (Sun et al., 2015). Protein abundance was detected by western blotting assay with antisera, including Nad9, Cox2, Cytc1, ATPase α-subunit and AOX as described previously (Sun et al., 2015; Xiu et al., 2016).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays were performed as described previously. DNA fragments without signal peptides of PPR101 and PPR231 were recombined into plasmids pGADT7 and pGBKT7. Plasmids were co-transformed and sprayed on dropout medium of DDO (SD/-Leu/-Trp), TDO (SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His), and QDO (SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade).

Results

PPR101 and PPR231 Are P-Type PPR Proteins Targeted to Mitochondria

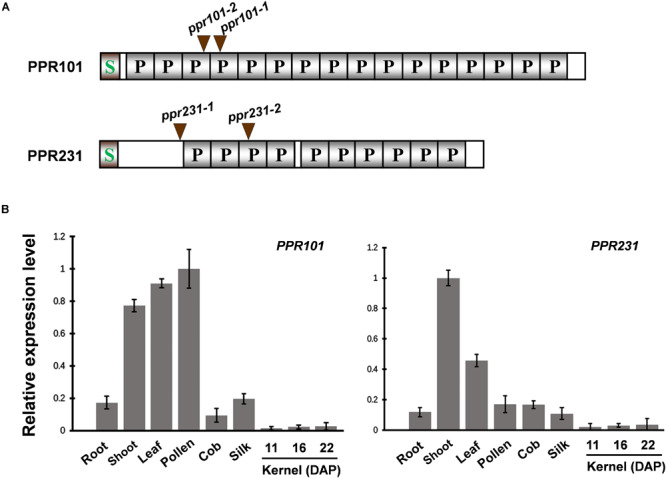

To characterize the function and the role of PPR proteins in plant growth and development, we analyzed multiple PPR genes and identified mutants from the UniformMu mutagenesis population (Mccarty et al., 2013). Two PPR genes are focused as they all encode P-type PPR proteins and are predicted to localize in mitochondria. PPR101 (GRMZM2G023999) contains 647 amino acids with 16 PPR motifs, and PPR231 (GRMZM2G018757) 526 amino acids with 10 PPR motifs (Figure 1A). A signal peptide was found in the N-terminus of each protein and no other domains were identified.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of PPR101 and PPR231. (A) Schematic presentation of PPR101 and PPR231. Two Mutator (Mu) insertion sites are labeled by brown triangles. P motifs are predicted by TPRpred (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/#/tools/tprpred). S, signal peptide. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of PPR101 and PPR231 expression in major maize tissues and developing kernels. ZmActin was used to normalize the quantifications. Values and error bars were means of three technical replicates, ±SD. DAP, days after pollination.

To examine the expression pattern of PPR101 and PPR231, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses were performed on major maize tissues and developing kernels. Results indicate that these two genes are expressed in various tissues with slightly different expression patterns (Figure 1B). The expression of PPR101 is relatively high in pollen, leaf and shoot, and low in root, silk, cob, especially in developing kernels. The expression of PPR231 is high in shoot, with relatively low in other tissues and developing kernels. These data suggest that rather than seed specific, these two PPRs are constitutive genes that have functions throughout plant growth and development. However, due to the embryo lethality caused by these two genes mutation, the influences in other tissues cannot be examined.

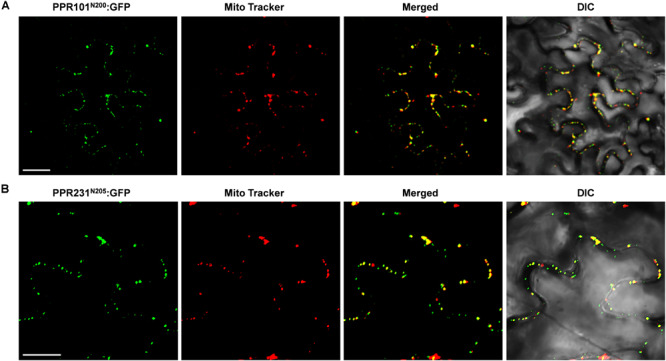

To experimentally determine the subcellular localization, we fused the full length PPR with GFP and transiently expressed the fusion protein in tobacco epidermal cells. However, expression of PPR101-GFP and PPR231-GFP did not produce any detectable signals. We then used the N-terminal 200 and 205 amino acids of PPR101 and PPR231, respectively, and fused with GFP. Expression of both constructs produced strong GFP signals in punctate dots that were merged with mitochondria as stained by MitoTracker Red, a marker of mitochondria (Figures 2A,B). These results suggest that PPR101 and PPR231 are targeted to mitochondria.

FIGURE 2.

Subcellular localization of PPR101 and PPR231. PPR101 and PPR231 are localized in mitochondria. The truncated protein with 200 amino acids of PPR101 (A) and 205 amino acids of PPR231 (B) were fused with GFP and transiently expressed in tobacco leaf epidermal cells and the GFP signals were detected by confocal fluorescent microscopy. Mitochondria are marked with MitoTracker. DIC, differential interference contrast; GFP, green fluorescence protein; N200, the N-terminal 200 amino acids of PPR101; N205, the N-terminal 205 amino acids of PPR231. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Loss-of-Function Mutation in PPR101 and PPR231 Impairs Seed Development in Maize

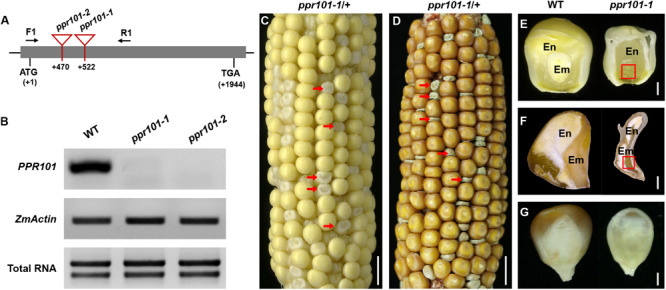

To reveal the function of these genes in plants, we isolated Mutator (Mu) insertional mutants from the maize UniformMu population (Mccarty et al., 2005). These seeds were planted and genotyped by PCR with gene specific primers and Mu-TIR primers. The insertion sites of each Mu element in the corresponding protein domains were indicated in Figure 1A. PPR101 gene contains no intron and PPR231 contains one intron. All the insertions are in coding region, thus disrupting the coding of proteins. For the PPR101 gene, two alleles have the Mu insertions at 522 bp and 470 bp downstream from the ATG of PPR101, named ppr101-1 and ppr101-2, respectively (Figure 3A). RT-PCR with primers across the insertion did not detect any expression of PPR101 (Figure 3B), suggesting that wildtype transcripts cannot be produced in the mutants. Self-crossed heterozygous plants for ppr101-1 and ppr101-2 produced ears segregating empty pericarp (emp) and wildtype kernels in a ratio of 1:3 (102:314, P < 0.05). The emp phenotype is tightly linked to the Mu insertion as only the heterozygous plants produce emp kernels. Crosses between ppr101-1 and ppr101-2 heterozygotes also produce emp mutants, confirming that the emp phenotype is caused by the mutation of PPR101 (GRMZM2G023999) (Supplementary Figure S1). Compared with the WT, the ppr101-1 kernels are small during the entire seed development process and the pericarps are collapsed at maturity. Both the endosperm and embryo development are defective with its embryogenesis arrested at the transition stage and the endosperm development stalled in ppr101-1. As the maternal pericarp continues its growth, this causes a cavity between the pericarp and the zygote seed (Figures 3C–G).

FIGURE 3.

Mutant analysis of the ppr101-1. (A) Schematic presentation of the PPR101 gene structure and positions of Mutator (Mu) insertions in two alleles. The gray box represents protein translated region, and black lines represent the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. Mu insertion sites of ppr101 alleles are indicated by red triangles. (B) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of PPR101 expression level in ppr101 mutants and the wildtype siblings at 12 DAP with primers PPR101-F1/R1. Expression was normalized with total RNA and ZmActin. (C,D) The selfed ear segregates 3:1 for the WT and ppr101-1 (red arrows) at 12 DAP (C) and mature stage (D). Scale bar = 1 cm. (E,F) The view of endosperm and embryo of the WT and ppr101-1 at 12 DAP (E) and mature stage (F). En, endosperm; Em, embryo. Red box indicates the embryo. Scale bar = 1 mm. (G) Germinal side of the WT and ppr101-1 mature kernels. Scale bar = 1 mm.

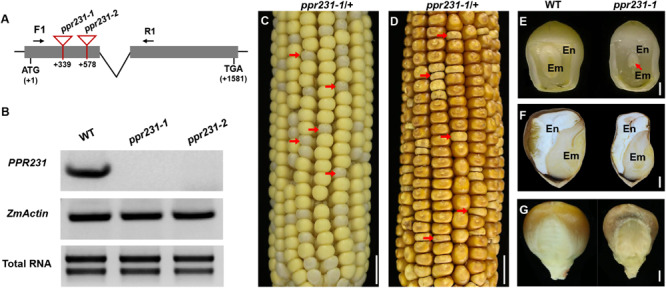

For the PPR231 gene, two alleles were isolated with Mu insertions at 339 bp and 578 bp downstream from the ATG, named ppr231-1 and ppr231-2 (Figure 4A). The selfed progeny of the ppr231 heterozygous plants produced mutants at an approximately 25% ratio (137:406, P < 0.05). Molecular and genetic analysis indicate that the phenotype is caused by the mutation of PPR231 (GRMZM2G018757) (Supplementary Figure S2). Wildtype PPR231 transcripts were not detected in the mutants (Figure 4B). The ppr231-1 mutant kernels show partially developed embryo and endosperm. No clear differentiation of shoot apex is detected in the embryo and the endosperm development is also delayed compared with the WT (Figures 4C–G). Both the ppr101 and ppr231 mutants are embryo-lethal and cannot germinate, implying that the two PPRs are essential to maize embryogenesis and endosperm development.

FIGURE 4.

Mutant analysis of the ppr231-1. (A) Schematic presentation of the PPR231 gene structure and positions of Mutator (Mu) insertions in two alleles. The gray boxes represent protein translated region, and black lines represent the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions and intron. Mu insertion sites of ppr231 alleles are indicated by red triangles. (B) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of PPR231 expression level in ppr231 mutants and the wildtype siblings at 12 DAP with primers PPR231-F1/R1. Expression was normalized with total RNA and ZmActin. (C,D) The selfed ear segregates 3:1 for the WT and ppr231-1 (red arrows) at 12 DAP (C) and mature stage (D). Scale bar = 1 cm. (E,F) The view of endosperm and embryo of the WT and ppr231-1 at 12 DAP (E) and mature stage (F). En, endosperm; Em, embryo. Red arrow indicates the embryo. Scale bar = 1 mm. (G) Germinal side of the WT and ppr231-1 mature kernels. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Embryogenesis and Endosperm Development Are Arrested in ppr101-1 and ppr231-1

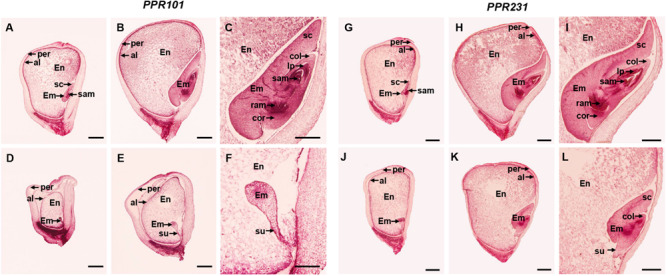

To further assess the developmental arrest in two mutants, we sectioned the homozygous and wildtype sibling kernels from the same segregating ear. At 9 DAP, the wildtype embryo differentiated a scutellum (sc), coleoptile (col), and shoot apical meristem (sam), reaching to the coleoptilar stage, and the endosperm was large and filled normally (Figure 5A). But the ppr101-1 embryo had undifferentiated embryo proper still attached to a suspensor, and its endosperm development was also hindered (Figure 5D). At 15 DAP, the wildtype embryo was well-developed and formed visible sc, col, coleorhizae (cor), sam, leaf primordia (lp) and root apical meristem (ram), reaching to the maturation stage. And the endosperm further developed, forming a plump starch filled endosperm tightly and wrapped by pericarp (Figures 5B,C). In ppr101-1, instead, the embryo remained at the transition stage with no obvious growth and differentiation, and the endosperm was small and underdeveloped (Figures 5E,F).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison in kernel development between ppr101-1, ppr231-1 mutant and wildtype sibling kernels. (A–F) Developmental analysis of the WT (A–C) and ppr101-1 (D–F) at 9 DAP (A,D) and 15 DAP (B,E). (C,F) are amplified embryo pictures of panels (B,E). (G–L) Developmental analysis of the WT (G–I) and ppr231-1 (J–L) at 9 DAP (G,J) and 15 DAP (H,K). (I,L) are amplified embryo pictures of panels (H,K). En, endosperm; Em, embryo; per, pericarp; al, aleurone; col, coleoptile; cor, coleorhizae; sam, shoot apical meristem; ram, root apical meristem; sc, scutellum; su, suspensor; lp, leaf primordia. Scale bars: (A,B,D,E,G,H,J,K) = 1.0 mm; (C,F,I,L) = 0.5 mm.

In ppr231-1, the arrest of seed development was not as severe as ppr101-1. At 9 DAP, the wildtype embryo reached to the coleoptilar stage (Figure 5G), whereas the mutant embryo development was delayed at the transition stage (Figure 5J). At 15 DAP, the wildtype embryo differentiated well with distinguishable sc, col, sam, lp, ram and cor, reaching to late embryogenesis stage (Figures 5H,I). In contrast, the mutant embryo was remained at the coleoptilar stage with indistinct sc and col (Figures 5K,L). Moreover, the endosperm development of ppr231-1 was slower than that of the WT at 9 and 15 DAP. These results indicate that the mutation of two PPRs hampers seed development and results in embryo lethality.

PPR101 and PPR231 Are Required for the Splicing of Mitochondrial Introns

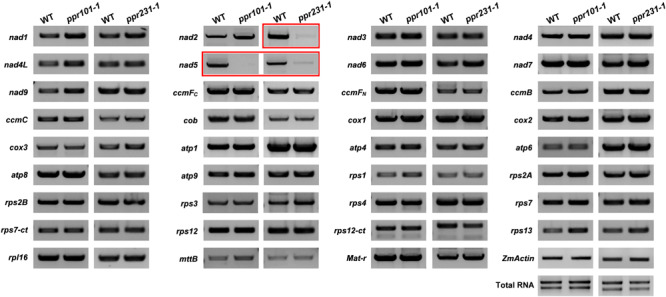

P-type PPR proteins have been reported to participate in organelle RNA metabolism such as intron splicing, RNA stabilization, and translation (Barkan and Small, 2014). To uncover the function of the two PPRs, we compared the expression level of mitochondrial transcripts of 35 protein coding genes between the WT and mutants. Specific primers used to amplify the transcripts are listed in Supplementary Table S1. RT-PCR analysis indicates that the level of nad5 transcript is dramatically reduced and nearly undetectable in ppr101-1. And the nad2 and nad5 transcript levels are decreased substantially in ppr231-1. No significant differences were detected in the level of other mitochondrial transcripts between the WT and mutants (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

RT-PCR analysis of expression level of 35 mitochondrial transcripts in the WT and mutants. The level of nad5 transcript is dramatically reduced and nearly undetectable in ppr101-1. And the level of nad2 and nad5 transcripts is decreased substantially in ppr231-1. The RNA was isolated from the same ear segregating for the wildtype and mutant kernels at 12 DAP. Expression was normalized with total RNA and ZmActin.

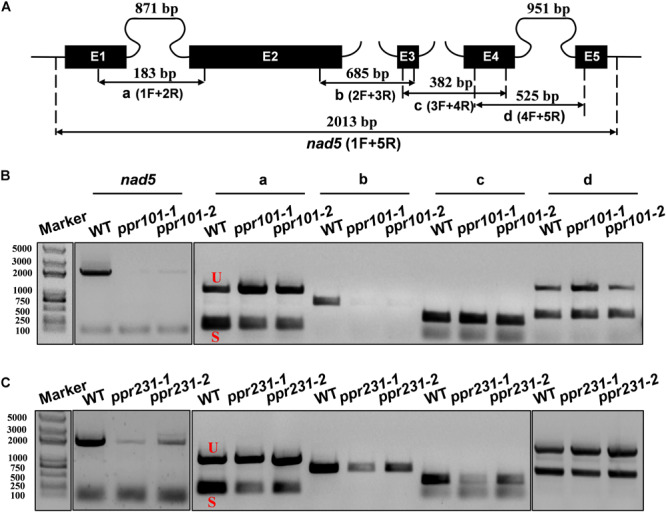

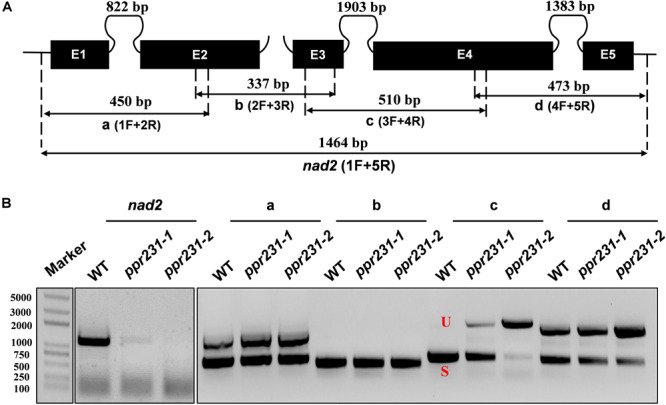

Maize mitochondrial nad5 has two trans-splicing introns (introns 2 and 3) and two cis-splicing introns (introns 1 and 4) (Figure 7A). nad2 contains one trans-splicing intron (intron 2) and three cis-splicing introns (introns 1, 3 and 4), (Figure 8A; Brown et al., 2014). The decrease of nad2 and nad5 transcripts in mutants may be caused by intron splicing defects. To test this possibility, RT-PCR was performed with primers anchored on neighboring exons across each intron. The results show that in the ppr101 mutants, the splicing of nad5 intron 1 is reduced and the splicing of nad5 intron 2 is nearly abolished, whereas the splicing of introns 3 and 4 is normal (Figure 7B). In the ppr231 mutants, the splicing of nad5 introns 1, 2, and 3 is decreased (Figure 7C). In addition, the cis-splicing of nad2 intron 3 is also reduced with the accumulation of unspliced fragment (Figure 8B). The larger fragments were sequenced and confirmed the presence of unspliced introns. PPR proteins are proposed to bind RNA nucleotides via the one PPR motif recognizing one ribonucleotide mechanism where the sixth amino acid of the first PPR motif and the first amino acid of the next PPR motif specify one nucleotide (Barkan et al., 2012; Takenaka et al., 2013). Based on these codes and with the aid of a web program4, we predicted the putative binding sequences of PPR101 and PPR231 with the target intron sequences (Supplementary Figure S3). The positions of these putative binding sites in the intron were marked in relative position to the donor or receptor site. An attempt to map these sequences on the intron domains was given up due to the high viability in assigning intron domains and unavailable trans-intron breaking ends.

FIGURE 7.

PPR101 is required for the splicing of nad5 introns 1 and 2, and PPR231 for nad5 introns 1, 2, 3. (A) Structure of the maize mitochondrial nad5 gene. Exons are indicated with black boxes. The closed and opened lines stand for cis-spliced and trans-spliced introns. The expected amplification products using different exon flanking primers are indicated (a–d). E1-E5: exon1-exon5. (B,C) RT-PCR analysis of intron-splicing deficiency of nad5 in the WT, ppr101 and ppr231 mutants. RNA was isolated from two alleles of mutant and wildtype kernels at 12 DAP. Exon–exon primers are used as indicated in panel (A). S and U indicate the spliced and unspliced PCR products, respectively.

FIGURE 8.

PPR231 is also essential to the splicing of nad2 intron3. (A) Structure of the maize mitochondrial nad2 gene. Exons are indicated with black boxes. The closed and opened lines stand for cis-spliced and trans-spliced introns. The expected amplification products using different exon flanking primers are indicated (a–d). E1-E5: exon1-exon5. (B) RT-PCR analysis of intron-splicing deficiency of nad2 in the WT and ppr231 mutants. RNA was isolated from two alleles of ppr231 mutant and wildtype kernels at 12 DAP. Exon–exon primers are used as indicated in panel (A). S and U indicate the spliced and unspliced PCR products, respectively.

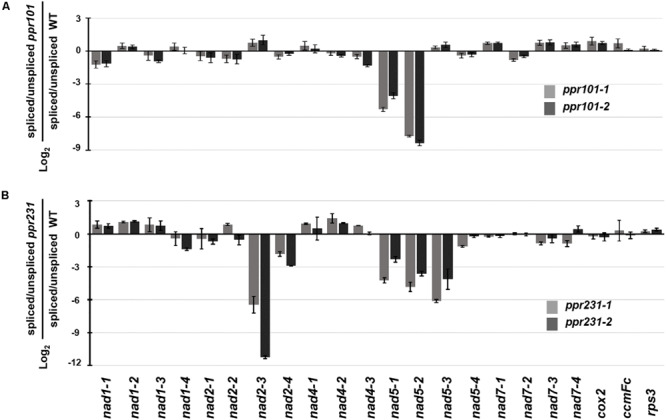

To independently verify the splicing defects in the ppr101 and ppr231 mutants, we performed qRT-PCR to examine the splicing efficiency of all the 22 group II introns in maize mitochondrial genome (Figure 9). Spliced and unspliced transcripts were amplified specially with two sets of primers. The splicing efficiency was calculated by the ratio of spliced to unspliced products of each transcript in the mutants normalized to the same ratio in the WT. Results indicate that the splicing efficiency of nad5 introns 1 and 2 is decreased in the ppr101 mutants (Figure 9A), and the splicing efficiency of nad5 introns 1, 2 and 3, and nad2 intron 3 is reduced in the ppr231 mutants (Figure 9B). No significant alteration in the splicing efficiency of other mitochondrial group II introns was detected. The RT-PCR and qRT-PCR results confirm that PPR101 is essential to the splicing of nad5 introns 1 and 2, whereas PPR231 is critical to the splicing of nad5 introns 1, 2, 3 and nad2 intron 3.

FIGURE 9.

Splicing efficiency analysis in the ppr101 and ppr231 mutants. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of all 22 group II introns in maize mitochondrial genes in the ppr101 (A) and ppr231 (B) mutants. Total RNA was isolated from two alleles of the ppr101 and ppr231 mutant and wildtype kernels at 12 DAP. Values is calculated by the log2 ratio of spliced to unspliced forms for each intron in two mutants compared with the WT. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of three biological replicates, ±SD.

Loss of Function in PPR101 and PPR231 Impairs Mitochondrial Complex I Assembly and Activity

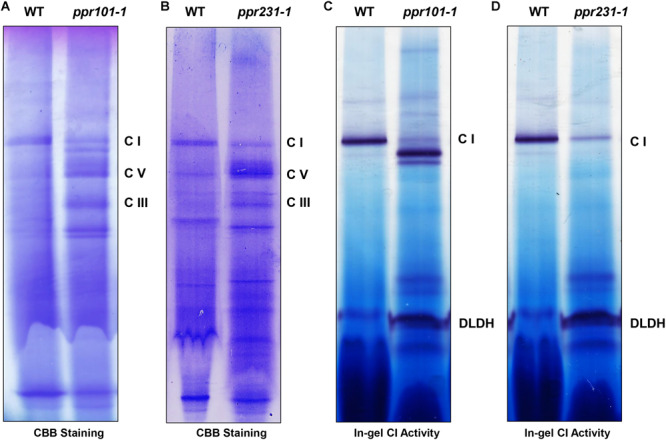

Complex I is composed of two arms, the “membrane arm” that embeds in the membrane and “peripheral arm” that protrudes into the matrix (Peters et al., 2013). Nad2 and Nad5 are key subunits of the membrane arm, hence the deficiency in nad2 and nad5 transcripts is predicted to affect mitochondrial complex I biogenesis. To assess the impact of PPR101 and PPR231 mutations on the complexes, we performed blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and in-gel NADH dehydrogenase activity assays. Results showed that the WT and mutants exhibited a different pattern of complex proteins (Figure 10). Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining showed that complex I was dramatically decreased while complex III and V were increased in two mutants compared with the WT (Figures 10A,B). In-gel NADH dehydrogenase activity assays indicated that the complex I activity disappeared at the holo-complex I position in ppr101-1, but appeared at positions of a smaller size, suggesting a possible accumulation of sub-complex I (Figure 10C). The ppr231-1 mutant also showed a reduction in the activity of complex I but did not show the NADH dehydrogenase activity in the sub-complexes, suggesting that such sub-complex I cannot be assembled in ppr231-1 (Figure 10D).

FIGURE 10.

The assembly and activity of mitochondrial complex I are affected in the ppr101-1 and ppr231-1 mutants. (A,B) Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) analysis of mitochondrial complexes assembly in ppr101-1 (A) and ppr231-1 (B). Crude mitochondrial proteins were isolated and separated according to Sun et al. (2015). The BN gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB). C I, complex I; C III, complex III; C V, complex V. (C,D) NADH dehydrogenase activity assay of complex I in ppr101-1 (C) and ppr231-1 (D). Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLDH) was used as a loading control.

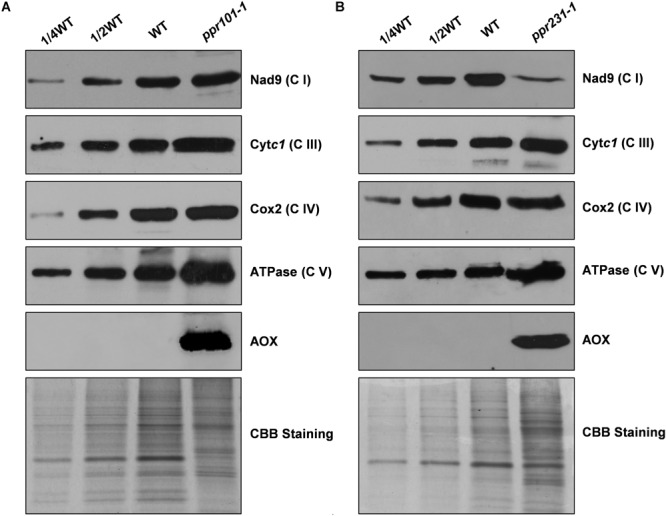

To examine the impact on protein abundance of mitochondrial complexes, western blotting assay was performed with specific antibodies against representative proteins of different mitochondrial complexes including Nad9 (complex I), Cytc1 (complex III), Cox2 (complex IV), and α subunit of ATPase (complex V). The results showed that the Nad9 (Complex I) level was dramatically decreased in ppr231-1 and but not in ppr101-1. A slight increase was detected in the level of Cytc1 and Cox2, but substantial increase was occurred in the level of ATPase in both mutants (Figure 11). These results together with the BN-PAGE and in-gel assays indicate that the loss-of-function mutation of PPR101 and PPR231 reduces the activity and assembly of complex I, which may affect the expression of components in other mitochondrial complexes.

FIGURE 11.

Accumulation of mitochondrial proteins in the ppr101-1 and ppr231-1 mutants. Western blotting analysis of mitochondrial proteins in the ppr101-1 (A) and ppr231-1 (B) with antibodies against Nad9, Cytc1, Cox2, ATPase, and AOX. Crude mitochondrial proteins of the WT and mutants were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. CBB-stained gel was used as reference of loading quantity.

Alternative Respiratory Pathway Is Activated in ppr101-1 and ppr231-1

The block of complex I has been shown to activate the expression of alternative oxidase (AOX) in the alternative pathway (De Longevialle et al., 2007; Toda et al., 2012). We then analyzed the expression of AOX at the RNA and protein level. The maize genome contains three AOX genes, AOX1 (AY059646.1), AOX2 (AY059647.1), and AOX3 (AY059648.1). RT-PCR and qRT-PCR results indicate that in two mutants, the expression level of AOX2 transcript is upregulated by 6 to 16 times in comparison with the WT (Supplementary Figure S4). Consistently, the AOX protein as detected by specific antibody was induced dramatically in two mutants (Figure 11). These results provide further evidence that the mutation of either PPR101 or PPR231 impairs complex I biogenesis, leading to dysfunction of mitochondrial respiratory chain.

Discussion

PPR101 and PPR231 Function in Intron Splicing in Maize Mitochondria

Through a genetic and molecular study, we revealed the molecular function of PPR101 and PPR231. PPR101 is required for the splicing of nad5 introns 1 and 2, and PPR231 for the splicing of nad5 introns 1, 2, 3, and nad2 intron 3 in mitochondria. This conclusion is supported by (1) All two proteins are localized in mitochondria; (2) two alleles of each mutant show identical defects in the splicing of the specific nad5 and nad2 introns; and (3) the deficiency in the splicing of nad5 and nad2 introns is corroborated by the dysfunction in the assembly and activity of mitochondrial complex I.

P-type PPR proteins have been implicated in RNA splicing, RNA stabilization and translation in plant organelle (Barkan and Small, 2014). We have not detected any other localization of these two proteins in compartments other than mitochondria although PPR proteins have been reported to localize in nucleus or dual-localize in chloroplasts and mitochondria. It is also unlikely that these two proteins have functions of RNA C-to-U editing although P-type PPR proteins also have been reported to function in RNA C-to-U editing (Doniwa et al., 2010; Leu et al., 2016). We sequenced all 35 gene transcripts in mitochondria and found no defect in C-to-U editing in two mutants.

In maize, several P-type PPR proteins have been reported to function in mitochondrial intron splicing. The loss of DEK2 leads to the decrease of nad1 intron 1 splicing efficiency and causes small kernels (Qi et al., 2017). EMP8 participates in the trans-splicing of nad1 intron 4 and cis-splicing of nad4 intron 1 and nad2 intron 1, and is responsible for mitochondrial complex I biogenesis (Sun et al., 2018). EMP16 is required for the cis-splicing of nad2 intron 4, the mutation of which influences the complex I assembly and activates the expression of AOX2, resulting in an empty pericarp phenotype (Xiu et al., 2016). DEK37 was reported to be required for the nad2 intron 1 splicing and seed development (Dai et al., 2018). The mutation of PPR20 impairs the splicing of nad2 intron 3, arresting the development of embryo and endosperm (Yang et al., 2019). EMP12 is implicated in the splicing of three nad2 introns and indispensable to complex I biogenesis (Sun et al., 2019). The loss-of-function of DEK41 affects the splicing of nad4 intron 3 and seed development (Zhu et al., 2019). EMP602 functioning on the splicing of nad4 introns 1 and 3, is associated with the formation of mitochondria and assembly of complex I (Ren et al., 2019). These studies indicate that PPR proteins play an essential role in seed development. Hence, characterizing more PPRs by reverse genetics approach will uncover the function of PPR proteins and elucidate the molecular mechanism of seed development.

PPR101 and PPR231 Are Essential to Complex I Biogenesis and Seed Development in Maize

Complex I is the major entry point for the respiratory chain and is located at the inner membrane of mitochondria. Nad2 and Nad5 are considered as antiporter-like subunits, similar to potential proton translocation sites, and are essential to the function of complex I (Efremov and Sazanov, 2011). Previous studies have reported about the splicing deficiency of nad2 or nad5 introns affecting complex I biogenesis. In Arabidopsis, the mutation of mTERF15 which is required for nad2 intron3 splicing reduced the activity and assembly of complex I (Hsu et al., 2014). The loss-of-function of RUG3 responsible for the splicing of nad2 introns 2 and 3 impairs the complex I biogenesis (Kuhn et al., 2011). Tang2 and Otp439 are involved in nad5 introns splicing. The mutation of two genes almost blocks the assembly and activity of complex I (Francs-Small et al., 2012). In maize, the Emp10, Emp12, Emp16, PPR20 are required for nad2 introns splicing. The mutants of these genes all generate impaired complex I biogenesis (Xiu et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019). In our study, the defects in the splicing of nad2 and nad5 introns which resulted in the lack of Nad2 and Nad5, impede the assembly and activity of complex I in two mutants (Figure 10). Results suggest the significant role of PPR101 and PPR231 in nad2 and nad5 introns splicing and the complex I biogenesis.

As Complex I is essential to mitochondrial function, the defect of complex I will hazard the mitochondrial respiratory chain and cause detrimental consequence to seed development (Noctor et al., 2007). Therefore, the block of complex I biogenesis may has close correlation with seed development. Our results indicated that the assembly and activity of complex I reduced to different extent in ppr101-1 and ppr231-1 (Figure 10), thus resulting in different phenotypes of two mutants. NADH oxidase activity at the position expected for complex I was almost undetectable in ppr101-1, which generated the empty pericarp phenotype. In ppr231-1, complex I activity was reduced but still detectable which was not as severe as the ppr101-1, resulting in the small kernel phenotype. In previous studies, different degree of inhibition of complex I activity producing different maize kernel phenotypes also happened. In emp8, emp10, emp11, emp12, emp16 and emp602 mutants, the activity of complex I is almost abolished, which dramatically arrest the embryogenesis and endosperm development, thus generating empty pericarp maize kernels (Xiu et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017, 2019; Zhang et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018). However, the complex I activity in smk1, dek2, and dek37 mutants is merely reduced, which alleviates the arrestment of embryo and endosperm development, producing a small kernel phenotype (Li et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2017; Dai et al., 2018). Therefore, results highlight the essential function of PPR101 and PPR231 in intron splicing, mitochondrial complex I biogenesis and seed development in maize.

Characterization of the Two Mutants Sheds Lights to the Regulation of Complex I Subunit Accumulation

While all these two mutants are deficient of complex I, however, the impact on the accumulation of Nad9, a component of complex I, is different. Nad9 is accumulated to a wildtype level in ppr101-1, but drastically decreased in ppr231-1 (Figure 11). Our data suggest that the decreased Nad9 accumulation in ppr231-1 is not caused by either a decreased transcription or defect in the translation machinery. Because nad9 is normally transcribed (Figure 6), and Cytc1, Cox2 and ATPase which are encoded by the mitochondria are translated normally in ppr231-1 (Figure 11). The same phenomenon was also reported in previous study. In two PPR mutants, mtl1 and mtsf1, which were defective in the nad7 mRNA translation and nad4 transcript stability, respectively, the function of complex I respiratory was impaired and the level of Nad9 translation was decreased about 2-fold in two mutants. However, compared with the WT, the level of nad9 transcript was unchanged in mtl1 and increased slightly in mtsf1. This suggests that the dysfunction of complex I may cause a negative feedback regulation on the level of Nad9 specifically (Planchard et al., 2018).

The reduced level of Nad9 is probably caused by protein degradation. The degradation of Nad9 in ppr231-1 may imply a regulatory mechanism on the turnover of Nad9. Owing to defects in intron splicing, the ppr101 mutant is deficient of Nad5, whereas the ppr231 mutant is deficient of Nad5 and Nad2. This indicates that deficiency of both Nad2 and Nad5 or Nad2 alone can trigger the degradation of Nad9. Previous studies have indicated that the deficiency of Nad2 itself will dramatically reduce the accumulation of Nad9 in maize. The emp16 mutant which is deficient in the splicing of nad2 intron 4 cannot accumulate Nad9 (Xiu et al., 2016), the emp12 mutant which is defective in the splicing of nad2 introns 1, 2 and 4 cannot accumulate Nad9 either (Sun et al., 2019), and the ppr20 mutant which is defective in the splicing of nad2 intron 3 also abolish the accumulation of Nad9 (Yang et al., 2019). Instead, defects in components of other mitochondrial complexes as in maize emp9, emp18 and smk4 mutants do not affect Nad9 accumulation (Yang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Also defects in other subunits of complex I, as in Arabidopsis nmat4 and ppr19 mutants, the nad1 intron splicing deficiency blocks the complex I activity dramatically, do not reduce Nad9 abundance (Cohen et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2017). These results suggest a regulatory mechanism exists in plants where a deficiency of Nad2 triggers the degradation of Nad9 in maize mitochondria.

Evidence suggests that this regulatory mechanism may be related to the assembly process of complex I in plants. A recent study has shown that the assembly of complex I follows a modular pathway in Arabidopsis (Ligas et al., 2019). In this pathway, Nad2 assembles into the main PP module, Nad5 assembles into the PD module, and Nad9 assembles into the matrix arm via the Q module. Then the PP module assembles with the matrix arm to form complex I∗, and sequentially assembles with the PD module to form the complete complex I (Ligas et al., 2019). Although the assembly of complex I in maize is not yet known, the present data suggest that defects in the PD module as in ppr101 mutant do not trigger the degradation of Nad9 in the Q module, but defects in the PP module do which is observed in ppr231 mutant. It is possible that when the Q module cannot assemble into the PP module, Q module subunits are degraded, which include Nad7, Nad9, and other proteins. Following this reasoning, it would be interesting to check the accumulation of all the Q module matrix arm subunits in two mutants. Unfortunately, we do not have the antibodies.

This conclusion is also supported by our results on complex I assembly. In ppr101 mutant, the formation of sub-complex I was detected, but not in ppr231 mutant (Figure 10). The sub-complex I may be the assembled PP module with the matrix arm but without the PD module according to the pathway in Arabidopsis (Ligas et al., 2019).

Splicing of Single Intron Requires Multiple Splicing Factors in Mitochondria

PPR101 and PPR231 are required for multiple introns splicing, and meanwhile, they have functional overlap in the splicing of specific introns. Specifically, they are all required for the splicing of nad5 introns 1 and 2. As previously reported, in Arabidopsis, a CRM protein, mCSF1 is participated in the splicing of nad5 introns 1, 2, 3, and possibly 4 (Zmudjak et al., 2013); OTP439 and TANG2, two PPR proteins are involved in the splicing of nad5 introns 2 and 3, respectively (Colas et al., 2014). In maize, ZmSMK9 is required for the splicing of nad5 introns 1 and 4 (Pan et al., 2019). These results imply that the splicing of a single intron requires multiple splicing factors.

It seems that these splicing factors can be divided into two categories. The first class, like CRM, RNA helicases and intron maturases can be taken as general splicing factors which function in multiple group II introns splicing. They may constitute the core of a spliceosome, and therefore are essential to mitochondrial introns removal. The second class of splicing factors include PPR proteins, like OTP439, TANG2, SMK9, PPR101, and PPR231. They are likely to perform as assistant factors in recruiting other mitochondrial splicing factors and/or sustaining the stability and improving the activity of this spliceosome when splicing on specific introns.

Previous studies have pointed out that PPRs have the capability to form complexes, and they may cooperate to form a specific spliceosome in mitochondrial introns splicing, such as PPR10 (Yin et al., 2013), PNM1 (Hammani et al., 2011), and GRP23 (Ding et al., 2006). PNM1 is reported to be involved in a 120 kDa complex (Hammani et al., 2011; Senkler et al., 2017). GRP23 is identified in a 160 kDa complex including PMH2 and nMAT2 in mitochondria (Senkler et al., 2017; Zmudjak et al., 2017). As PPR101 and PPR231 overlap in the splicing of a specific nad5 intron, it is reasonable to conjecture that they have interaction. However, yeast two-hybrid assay revealed no direct interaction between them (Supplementary Figure S5). These phenomena also happened in previous studies. EMP12 and EMP16 are implicated in cis-splicing of nad2 intron 4 but fail to interact physically (Sun et al., 2019). Similarly, PPR20 and Zm_mTERF15 are all specifically involved in nad2 intron 3 splicing. But there is no interaction between them (Yang et al., 2019).

The molecular mechanism of PPR proteins in splicing is still ambiguous, but possible reasons with respect to this are speculated as follows: (1) They function independently in a complex without physical interaction directly. (2) They probably have interaction, but like the nuclear spliceosome, they constitute a highly dynamic complex, which acts transiently or unstably on multiple introns splicing. (3) They facilitate intron splicing not by protein-protein interaction. As PPRs embrace different RNA-binding domain, they can bind intron sequences independently at different sites, help introns folding correctly and maintain the configuration of intron sequences in a catalytically active state without interaction.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

HY and B-CT designed the research. HY performed most of the experiments. ZX and XL participated in subcellular localization experiments. LW performed the western blotting assay. S-KC and FS participated in the BN gel experiment. HY, ZX, and B-CT analyzed the data. HY and B-CT wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Dr. Tsuyoshi Nakagawa (Shimane University, Japan) for the pGWB vectors and the Maize Genetic Stock Center for providing the maize seeds.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Nos. 31630053 and 91735301 to B-CT; Project No. 31700210 to ZX) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (Project No. 2017M622183 to ZX).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00732/full#supplementary-material

References

- Barkan A., Rojas M., Fujii S., Yap A., Chong Y. S., Bond C. S., et al. (2012). A combinatorial amino acid code for RNA recognition by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002910. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan A., Small I. (2014). Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65 415–442. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonen L. (2008). Cis- and trans-splicing of group II introns in plant mitochondria. Mitochondrion 8 26–34. 10.1016/j.mito.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. G., Francs-Small C. C. D., Ostersetzer-Biran O. (2014). Group II intron splicing factors in plant mitochondria. Front. Plant Sci. 5:35. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger G., Gray M. W., Lang B. F. (2003). Mitochondrial genomes: anything goes. Trends Genet. 19 709–716. 10.1016/j.tig.2003.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M., Li S., Sun F., Sun Q., Zhao H., Ren X., et al. (2017). Emp10 encodes a mitochondrial PPR protein that affects the cis-splicing of nad2 intron 1 and seed development in maize. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 91:132. 10.1111/tpj.13551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Feng F., Qi W., Xu L., Yao D., Wang Q., et al. (2017). Dek35 encodes a PPR protein that affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad4 intron 1 and seed development in maize. Mol. Plant 10 427–441. 10.1016/j.molp.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Gutmann B., Zhong X., Ye Y., Fisher M. F., Bai F., et al. (2016). Redefining the structural motifs that determine RNA binding and RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in land plants. Plant J. 85 532–547. 10.1111/tpj.13121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claire L., Charles A., Sébastien A., Mohammed B., Frédérique B., Clémence B., et al. (2004). Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16 2089–2103. 10.1105/tpc.104.022236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton S. W., Minx P., Fauron C. M.-R., Gibson M., Allen J. O., Sun H., et al. (2004). Sequence and comparative analysis of the maize NB mitochondrial genome. Plant Physiol. 136 3486–3503. 10.1104/pp.104.044602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Zmudjak M., Francs-Small C. C. D., Malik S., Shaya F., et al. (2014). nMAT4, a maturase factor required for nad1 pre-mRNA processing and maturation, is essential for holocomplex I biogenesis in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant J. 78 253–268. 10.1111/tpj.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas D. F.-S. C., Falcon D. L. A., Li Y., Lowe E., Tanz S. K., Smith C., et al. (2014). The pentatricopeptide repeat proteins TANG2 and organelle transcript processing439 are involved in the splicing of the multipartite nad5 transcript encoding a subunit of mitochondrial complex I. Plant Physiol. 165:1409. 10.1104/pp.114.244616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D. W., Luan S. C., Chen X. Z., Wang Q., Feng Y., Zhu C. G., et al. (2018). Maize Dek37 encodes a P-type PPR protein that affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 1 and Seed development. Genetics 208 1069–1082. 10.1534/genetics.117.300602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Longevialle A. F., Meyer E. H., Andres C., Taylor N. L., Lurin C., Millar A. H., et al. (2007). The pentatricopeptide repeat gene OTP43 is required for trans-splicing of the mitochondrial nad1 Intron 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 19 3256–3265. 10.1105/tpc.107.054841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y. H., Liu N. Y., Tang Z. S., Liu J., Yang W. C. (2006). Arabidopsis GLUTAMINE-RICH PROTEIN23 is essential for early embryogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear PPR motif protein that interacts with RNA polymerase II subunit III. Plant Cell 18 815–830. 10.1105/tpc.105.039495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniwa Y., Ueda M., Ueta M., Wada A., Kadowaki K., Tsutsumi N. (2010). The involvement of a PPR protein of the P subfamily in partial RNA editing of an Arabidopsis mitochondrial transcript. Gene 454 39–46. 10.1016/j.gene.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efremov R. G., Sazanov L. A. J. N. (2011). Structure of the membrane domain of respiratory complex I. Nature 476 414–420. 10.1038/nature10330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickbush T. H. J. C. B. (1999). Mobile introns: retrohoming by complete reverse splicing. Curr. Biol. 9 R11–R14. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80034-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francs-Small C. C. D., Kroeger T., Zmudjak M., Ostersetzer-Biran O., Rahimi N., Small I., et al. (2012). A PORR domain protein required for rpl2 and ccmFC intron splicing and for the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant J. 69 996–1005. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04849.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S., Small I. (2011). The evolution of RNA editing and pentatricopeptide repeat genes. New Phytol. 191 37–47. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. W., Burger G., Lang B. F. (1999). Mitochondrial evolution. Science 283 1476–1481. 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haili N., Arnal N., Quadrado M., Amiar S., Tcherkez G., Dahan J., et al. (2013). The pentatricopeptide repeat MTSF1 protein stabilizes the nad4 mRNA in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 6650–6663. 10.1093/nar/gkt337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haili N., Planchard N., Arnal N., Quadrado M., Vrielynck N., Dahan J., et al. (2016). The MTL1 pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for both translation and splicing of the mitochondrial nadh dehydrogenase subunit7 mRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 170 354–366. 10.1104/pp.15.01591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammani K., Barkan A. (2014). An mTERF domain protein functions in group II intron splicing in maize chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 5033–5042. 10.1093/nar/gku112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammani K., Gobert A., Hleibieh K., Choulier L., Small I., Giegé P. J. T. P. C. (2011). An Arabidopsis dual-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein interacts with nuclear proteins involved in gene expression regulation. Plant Cell 23 730–740. 10.1105/tpc.110.081638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpen T. W. J. M., Van, Katarina C., Marilise N., Dirk B., Bouwmeester H. J., et al. (2010). Nicotiana benthamiana as a production platform for artemisinin precursors. PLoS One 5:e14222. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh W.-Y., Liao J.-C., Chang C., Harrison T., Boucher C., Hsieh M.-H. (2015). The SLOW GROWTH 3 pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for the splicing of mitochondrial nad7 intron 2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 168 490–501. 10.1104/pp.15.00354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y. W., Wang H. J., Hsieh M. H., Hsieh H. L., Jauh G. Y. (2014). Arabidopsis mTERF15 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 3 splicing and functional complex I activity. PLoS One 9:e112360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler D., Schmidt-Gattung S., Binder S. (2010). The DEAD-box protein PMH2 is required for efficient group II intron splicing in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 72 459–467. 10.1007/s11103-009-9584-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A., Francs-Small C. C. D., Calder G., Mugford S. T., Tanz S., Lee B. R., et al. (2010). Identification of a pentatricopeptide repeat protein implicated in splicing of intron 1 of mitochondrial nad7 transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 285 32192–32199. 10.1074/jbc.M110.147603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger T. S., Watkins K. P., Friso G., Van Wijk K. J., Barkan A. (2009). A plant-specific RNA-binding domain revealed through analysis of chloroplast group II intron splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 4537–4542. 10.1073/pnas.0812503106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn K., Carrie C., Giraud E., Wang Y., Meyer E. H., Narsai R., et al. (2011). The RCC1 family protein RUG3 is required for splicing of nad2 and complex I biogenesis in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 67 1067–1080. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn K., Carrie C., Giraud E., Wang Y., Meyer E. H., Narsai R., et al. (2011). The RCC1 family protein RUG3 is required for splicing of nad2 and complex I biogenesis in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 67 1067–1080. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Han J. H., Park Y. I., Francs-Small C. D., Small I., et al. (2017). The mitochondrial pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR19 is involved in the stabilization of NADH dehydrogenase 1 transcripts and is crucial for mitochondrial function and Arabidopsis thaliana development. New Phytol. 215 202–216. 10.1111/nph.14528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu K. C., Hsieh M. H., Wang H. J., Hsieh H. L., Jauh G. Y. (2016). Distinct role of Arabidopsis mitochondrial P-type pentatricopeptide repeat protein-modulating editing protein. PPME, in nad1 RNA editing. RNA Biol. 13 593–604. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1184384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. J., Zhang Y. F., Hou M., Sun F., Shen Y., Xiu Z. H., et al. (2014). Small kernel 1 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein required for mitochondrial nad7 transcript editing and seed development in maize (Zea mays) and rice (Oryza sativa). Plant J. 79 797–809. 10.1111/tpj.12584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. L., Huang W. L., Yang H. H., Jiang R. C., Sun F., Wang H. C., et al. (2019). EMP18 functions in mitochondrial atp6 and cox2 transcript editing and is essential to seed development in maize. New Phytol. 221 896–907. 10.1111/nph.15425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligas J., Pineau E., Bock R., Huynen M. A., Meyer E. H. (2019). The assembly pathway of complex I in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 97 447–459. 10.1111/tpj.14133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Pook-Than J., Bonen L. J. N. A. R. (2006). Multiple physical forms of excised group II intron RNAs in wheat mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 2782–2790. 10.1093/nar/gkl328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., He J., Chen Z., Ren X., Hong X., Gong Z. (2010). ABA overly-sensitive 5 (ABO5), encoding a pentatricopeptide repeat protein required for cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 3, is involved in the abscisic acid response in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63 749–765. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. J., Xiu Z. H., Meeley R., Tan B. C. (2013). Empty pericarp5 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein that is required for mitochondrial RNA editing and seed development in maize. Plant Cell 25 868–883. 10.1105/tpc.112.106781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurin C., Andres C., Aubourg S., Bellaoui M., Bitton F., Bruyere C., et al. (2004). Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16 2089–2103. 10.1105/tpc.104.022236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W., Herrmann R. G. J. P. P. (1998). Gene transfer from organelles to the nucleus: how much, what happens, and why? Plant Physiol. 118 9–17. 10.1104/pp.118.1.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W., Roettger M., Kloesges T., Thiergart T., Woehle C., Gould S., et al. (2012). Modern endosymbiotic theory: Getting lateral gene transfer into the equation. Endocytob. Cell Res. 23 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mccarty D. R., Mark Settles A., Suzuki M., Tan B. C., Latshaw S., Porch T., et al. (2005). Steady-state transposon mutagenesis in inbred maize. Plant J. 44 52–61. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccarty D. R., Suzuki M., Hunter C., Collins J., Avigne W. T., Koch K. E. (2013). Genetic and molecular analyses of UniformMu transposon insertion lines. Methods Mol. Biol. 1057 157–166. 10.1007/978-1-62703-568-2_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G., De Paepe R., Foyer C. H. J. T. I. P. S. (2007). Mitochondrial redox biology and homeostasis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 12 125–134. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova O., Belfort M. J. T. I. G. (2017). Mobile group II introns as ancestral eukaryotic elements. Trends Genet. 33 773–783. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z., Liu M., Xiao Z., Ren X., Zhao H., Gong D., et al. (2019). ZmSMK9, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein, is involved in the cis-splicing of nad5, kernel development and plant architecture in maize. Plant Sci. 288 110205. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K., Belt K., Braun H.-P. (2013). 3D gel map of Arabidopsis complex I. Front Plant Sci. 4:153. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planchard N., Bertin P., Quadrado M., Dargel-Graffin C., Hatin I., Namy O., et al. (2018). The translational landscape of Arabidopsis mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 6218–6228. 10.1093/nar/gky489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle A. M. (2016). Group II Intron Self-Splicing. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 45 183–205. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-011149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W., Yang Y., Feng X., Zhang M., Song R. (2017). Mitochondrial Function and Maize Kernel Development Requires Dek2, a Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein Involved in nad1 mRNA Splicing. Genetics 205 239–249. 10.1534/genetics.116.196105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R. C., Wang L. L., Zhang L., Zhao Y. J., Wu J. W., Wei Y. M., et al. (2020). DEK43 is a P-type pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein responsible for the Cis-splicing of nad4 in maize mitochondria. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 62 299–313. 10.1111/jipb.12843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Pan Z., Zhao H., Zhao J., Cai M., Li J., et al. (2017). EMPTY PERICARP11 serves as a factor for splicing of mitochondrial nad1 intron and is required to ensure proper seed development in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 68 4571–4581. 10.1093/jxb/erx212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Fan K., Fang T., Zhang J., Yang L., Wang J., et al. (2019). Maize Empty pericarp602 encodes a P-type PPR protein that is essential for seed development. Plant Cell Physiol. 60 1734–1746. 10.1093/pcp/pcz083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samach A., Melamed-Bessudo C., Avivi-Ragolski N., Pietrokovski S., Levy A. A. (2011). Identification of plant RAD52 homologs and characterization of the Arabidopsis thaliana RAD52-like genes. Plant Cell 111:091744. 10.1105/tpc.111.091744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Linneweber C., Lampe M.-K., Sultan L. D., Ostersetzer-Biran O. J. B. (2015). Organellar maturases: a window into the evolution of the spliceosome. Biochim. Biophys Acta 1847 798–808. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkler J., Senkler M., Eubel H., Hildebrandt T., Lengwenus C., Schertl P., et al. (2017). The mitochondrial complexome of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 89 1079–1092. 10.1111/tpj.13448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Li C., Mccarty D. R., Meeley R., Tan B. C. (2013). Embryo defective12 encodes the plastid initiation factor 3 and is essential for embryogenesis in maize. Plant J. 74 792–804. 10.1111/tpj.12161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Wang X., Bonnard G., Shen Y., Xiu Z., Li X., et al. (2015). Empty pericarp7 encodes a mitochondrial E-subgroup pentatricopeptide repeat protein that is required for ccmFN editing, mitochondrial function and seed development in maize. Plant J. 84 283–295. 10.1111/tpj.12993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Xiu Z., Jiang R., Liu Y., Zhang X., Yang Y. Z., et al. (2019). The mitochondrial pentatricopeptide repeat protein EMP12 is involved in the splicing of three nad2 introns and seed development in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 70 963–972. 10.1093/jxb/ery432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Zhang X., Shen Y., Wang H., Liu R., Wang X., et al. (2018). The pentatricopeptide repeat protein EMPTY PERICARP8 is required for the splicing of three mitochondrial introns and seed development in maize. Plant J. 95 919–932. 10.1111/tpj.14030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetlove L. J., Fait A., Nunes-Nesi A., Williams T., Fernie A. R. J. C. R. I. P. S. (2007). The mitochondrion: an integration point of cellular metabolism and signalling. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 26 17–43. 10.1080/07352680601147919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka M., Zehrmann A., Brennicke A., Graichen K. (2013). Improved computational target site prediction for pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factors. PLoS One 8:e65343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B. C., Chen Z., Yun S., Zhang Y., Lai J., Sun S. S. M. (2011). Identification of an active new mutator transposable element in maize. G3 Genesgenetics 1 293–302. 10.1534/g3.111.000398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T., Fujii S., Noguchi K., Kazama T., Toriyama K. (2012). Rice MPR25 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein and is essential for RNA editing of nad5 transcripts in mitochondria. Plant J. 72 450–460. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Aube F., Planchard N., Quadrado M., Dargel-Graffin C., Nogue F., et al. (2017). The pentatricopeptide repeat protein MTSF2 stabilizes a nad1 precursor transcript and defines the 3 end of its 5-half intron. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 6119–6134. 10.1093/nar/gkx162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Aube F., Quadrado M., Dargel-Graffin C., Mireau H. (2018). Three new pentatricopeptide repeat proteins facilitate the splicing of mitochondrial transcripts and complex I biogenesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 69 5131–5140. 10.1093/jxb/ery275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Sun H., Kwon W. S., Jin H., Yang D. C. (2019). SMALL KERNEL 4. Mitochond. DNA 20 41–45. 10.1080/19401730902856738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu Z., Sun F., Shen Y., Zhang X., Jiang R., Bonnard G., et al. (2016). EMPTY PERICARP16 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 4 cis-splicing, complex I assembly and seed development in maize. Plant J. 85 507–519. 10.1111/tpj.13122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Z., Ding S., Wang H. C., Sun F., Huang W. L., Song S., et al. (2017). The pentatricopeptide repeat protein EMP9 is required for mitochondrial ccmB and rps4 transcript editing, mitochondrial complex biogenesis and seed development in maize. New Phytol. 214 782–795. 10.1111/nph.14424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Z., Ding S., Wang Y., Wang H. C., Liu X. Y., Sun F., et al. (2019). PPR20 is required for the cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 3 and seed development in maize. Plant Cell Physiol. 61 370–380. 10.1093/pcp/pcz204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P., Li Q., Yan C., Liu Y., Liu J., Yu F., et al. (2013). Structural basis for the modular recognition of single-stranded RNA by PPR proteins. Nature 504 168–171. 10.1038/nature12651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. F., Suzuki M., Sun F., Tan B. C. (2017). The mitochondrion-targeted pentatricopeptide repeat78 protein is required for nad5 mature mRNA stability and seed development in maize. Mol. Plant 10 1321–1333. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Jin G., Fang P., Zhang Y., Feng X., Tang Y., et al. (2019). Maize pentatricopeptide repeat protein DEK41 affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad4 intron 3 and seed development. J. Exp. Bot. 70 3795–3808. 10.1093/jxb/erz193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmudjak M., Francs-Small C. C. D., Keren I., Shaya F., Belausov E., et al. (2013). mCSF1, a nucleus-encoded CRM protein required for the processing of many mitochondrial introns, is involved in the biogenesis of respiratory complexes I and IV in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 199 379–394. 10.1111/nph.12282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmudjak M., Shevtsov S., Sultan L., Keren I., Ostersetzer-Biran O. J. I. J. O. M. S. (2017). Analysis of the roles of the Arabidopsis nMAT2 and PMH2 proteins provided with new insights into the regulation of group II intron splicing in land-plant mitochondria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:2428. 10.3390/ijms18112428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.