Abstract

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), due to their intrinsic resistance to various commonly used antibiotics and their malleable genome, make the treatment of infections caused by these bacteria less effective. The aims of this work were to characterize isolates of Enterococcus spp. that originated from processed meat, through phenotypic and genotypic techniques, as well as to detect putative antibiotic resistance biomarkers. The 19 VRE identified had high resistance to teicoplanin (89%), tetracycline (94%), and erythromycin (84%) and a low resistance to kanamycin (11%), gentamicin (11%), and streptomycin (5%). Based on a Next-Generation Sequencing NGS technique, most isolates were vanA-positive. The most prevalent resistance genes detected were erm(B) and aac(6’)-Ii, conferring resistance to the classes of macrolides and aminoglycosides, respectively. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS) analysis detected an exclusive peak of the Enterococcus genus at m/z (mass-to-charge-ratio) 4428 ± 3, and a peak at m/z 6048 ± 1 allowed us to distinguish Enterococcus faecium from the other species. Several statistically significant protein masses associated with resistance were detected, such as peaks at m/z 6358.27 and m/z 13237.3 in ciprofloxacin resistance isolates. These results reinforce the relevance of the combined and complementary NGS and MALDI-TOF MS techniques for bacterial characterization.

Keywords: Enterococcus spp., processed meat, antibiotic resistance, next-generation sequencing, MALDI-TOF MS

1. Introduction

Enterococci are commensal bacteria known for their incidence in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals [1]. Enterococcus spp., more specifically Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis, have stood out as the main nosocomial pathogens [2]. Due to their high adaptive capacity, they can be present in different environments, such as soil and water, and have also been found in food products [3]. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are one of the greatest clinical challenges today, because VRE often possess determinants that confer resistance to several classes of antimicrobials and also because of their malleable genome that allows them to easily acquire antibiotic resistance genes, via plasmids and transposons [2,4,5].

The increasing demands for meat lead to the use of antibiotics as food promoters in livestock, which, in turn, lead to a selective pressure increase in livestock gut microbiota for antibiotic-resistant bacteria [6]. A relationship between the use of antibiotics in farm animals and bacterial resistance has been observed in several studies and clinical trials. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, from animal sources, have been found in meat products available in food retail stores and as a cause of clinical infections and subclinical colonization in humans [7]. For years, avoparcin, a glycopeptide antibiotic analogue of vancomycin, was used in European countries as a growth promoter in animal production [2]. Despite the banning of avoparcin in 1997 for animal use, it’s intense use probably potentiated the prevalence of VRE in animals. Bacterial resistance has implications for human health, generally affecting agricultural workers, through direct contact and passing through the environment and food products [6].

Infections with VRE are more difficult to treat than infection with vancomycin-susceptible enterococci (VSE) [8,9]. The resistance to vancomycin can be mediated by nine different types of van cluster genes (vanA -B, -C, -D, -E, -G, -L, -M, and -N) and we can distinguish them based on their physical location (encoded in the core genome or on a mobile genetic element); the level of resistance they confer; the specific glycopeptides to which they confer resistance (often distinguished operationally as providing resistance to both vancomycin and teicoplanin, or providing resistance to vancomycin but not teicoplanin); whether resistance is inducible or constitutively expressed; and the type of peptidoglycan precursor that is produced by their gene products. [10,11]. While the vanC gene characterizes the natural intrinsic resistance in some enterococci species, the others encode acquired resistance [12].

As mentioned, enterococci are intrinsically resistant to aminoglycosides and can acquire resistance genes to other antimicrobial classes [13,14]. However, high-level resistance to aminoglycosides (HLGR) is usually acquired on a mobile element that encodes an aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme. Such an enzyme is usually the bifunctional aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme, AAC(6′)-Ie-APH(2′′)-Ia, which is encoded by the aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2′′)-Ia gene, reducing the effect of aminoglycosides except for streptomycin [9,11]. Furthermore, among gentamicin-resistant strains, three aminoglycoside resistance genes, i.e., aph(2′′)-Ib, aph(2′′)-Ic, and aph(2′′)-Id, have been reported. The ant(4′)-Ia and aph(3′)-IIIa genes encode resistance to various aminoglycosides as well [4,9,15]. Thus, in spite the intrinsic resistance, aminoglycosides are still used in the treatment of enterococcal infections but at high concentrations to prevent intrinsic resistance.

Moreover, enterococci also show resistance to macrolides, and their major determinants of resistance are ribosomal target modification by 23S rRNA methylases encoded by erm genes and efflux pump systems encoded by msr and mefA/E genes [9,16]. Enterococci that carry erm genes can result in inducible or constitutive resistance to all macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B antibiotics. Alternatively, resistance to streptogramin B and some macrolide antibiotics is induced by the msrA gene [9,17].

Antibiotic resistance has been explored in many microorganisms as has the study of proteins associated with different mechanisms [18,19]. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS) produces spectra capable of discriminating strains of various types of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [20] and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, respectively [21], demonstrating great utility for the subtyping of strains [22].

As antibiotic-resistant bacteria can make it difficult to treat patients with complex infections, rapid and effective detection of resistance mechanisms can be vital in choosing the best antimicrobial [19]. For this reason, the proteomics approach becomes an extremely important tool for the identification of expressed proteins in a differentiated way and for the discovery of new biomarkers in order to understand which proteins are more or less abundant in a diseased state compared to the healthy state [23,24]. As biomarkers are discovered, inclusive information on the nature of proteins and their expression in relation to antimicrobial agents and resistance mechanisms should be stored in databases [25].

Thus, we aimed to identify VRE from processed meat (hamburgers, meatballs, and minced meat), investigate antimicrobial resistance, and find biomarkers of resistance in the Enterococcus genus, which will also be important for VRE from other reservoirs, as bacteria that can be studied in a One Health context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Bacterial Isolation

Between January 2018 and October 2019, one hundred and twenty-nine packages of different processed meat samples were purchased from six different supermarkets in northern Portugal. We analyzed a total of 43 packs of each processed meat sample: hamburgers, meatballs, and minced meat. All the samples were sealed in sterile plastic bags and kept at 4 °C prior to analysis.

The samples (25 g) were aseptically weighed into sterile bags, diluted with 200 mL sterile buffered peptone water, homogenized in a stomacher (Stomacher® 400 Circulator, Seward, London, UK) for about 5 min, and then 0.1 mL was spread onto Slanetz-Bartley agar plates (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) supplemented with vancomycin (4 μg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. One colony per Slanetz-Bartley agar plate (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) supplemented with vancomycin with typical enterococcal morphology was identified to the genus level by cultural characteristics, Gram staining, a catalase test, and bile-esculin reaction.

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested by the disk diffusion method [26], according to the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [27] for enterococci. The susceptibility of each enterococcal isolate was tested for 11 antibiotics: vancomycin (30 mg), teicoplanin (30 mg), ampicillin (10 mg), streptomycin (300 mg), gentamicin (120 mg), kanamycin (120 mg), chloramphenicol (30 mg), tetracycline (30 mg), erythromycin (15 mg), quinupristin-dalfopristin (15 mg), and ciprofloxacin (5 mg). Only the category of high-level resistance was considered for streptomycin, gentamicin, and kanamycin. Enterococcus faecalis strain ATCC 29212 and Staphylococcus aureus strain ATCC 25923 were used as quality control organisms.

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing, Genome Assembly, and Gene Detection

Bacterial DNA was extracted from overnight cultures with a DNeasy Ultraclean Microbial Kit ™ (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer. The whole genome sequence (WGS) of strains was determined by de novo assembly of 2 x 150-bp paired-end reads generated with Illumina sequencing technology (San Diego, CA, USA) using assembler SPAdes [28], Burrows-Wheeler Aligner [29], and Pilon [30] for final polishing. The antibiotic resistance genes were characterized with the ARIBA [31] package by mapping short reads against a manually curated and updated database of resistance-associated genes derived from CARD and Resfinder [32,33].

2.4. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

Bacterial growth was performed on Levine agar medium with and without antibiotic, following the CLSI standards [27]. The protein extracts were obtained from intact bacterial cells using a quick method described by Freiwald and Sauer [34]. The analyses were performed with an Autoflex Speed (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) by using the following parameters: linear mode, positive-ion extraction with voltage 19.56 kV at source 1 and 18.09 kV at source 2, delay time about 160 ns. For each extracted colony, a spectrum was obtained from the sum of three thousands laser shots at the frequency of 1000 Hz. A calibrant spot was analyzed before each isolate analysis by summing four thousands laser shots at the frequency of 1000 Hz.

2.5. Statistics and Bioinformatics Analysis of Spectra

The sample mass spectra were analyzed using ClinProToolsTM software (version 3.0, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), which includes three types of machine learning algorithms to generate classification models: quick classifier (QC), genetic algorithm (GA), and supervised neural network (SNN). The selected spectra were submitted to the three algorithms, QC, GA, and SNN, where the cross validation is based on the precision of the algorithm in the correct assignment of a random sample to the correct group. For each peak, the analysis of the operational characteristic of the receiver (ROC) was performed based on the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Isolation

A total of 19 vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolates were recovered from the 129 samples of processed meat. The distribution was the following: seven isolates from hamburgers; six isolates from meatballs; and six isolates from minced meat. After mass spectrometry species identification, we identified 14 isolates of Enterococcus faecium, three isolates of Enterococcus gallinarum, and two isolates of Enterococcus durans.

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Study

All strains showed resistance to three or more antimicrobials, in addition to vancomycin. Higher incidence of resistance was observed for teicoplanin (n = 17), erythromycin (n = 16), and tetracycline (n = 16). Additionally, fourteen isolates showed resistance to ampicillin, and six were resistant to ciprofloxacin. High-level resistance to aminoglycosides was also detected in two isolates that showed high-level resistance to kanamycin and gentamicin and one isolate that showed high-level resistance to streptomycin. Furthermore, all isolates were susceptible to chloramphenicol and quinupristin-dalfopristin.

3.3. Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

After whole-genome sequencing, with Illumina technology (San Diego, CA, USA), and de novo assembly, we detected that sixteen of the nineteen VRE isolates (E. faecium and E. durans) were vanA positive and two E. gallinarum were vanC1 positive. Interestingly, one E. gallinarum isolate showed the combination vanA + vanC1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Nineteen Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolates Recovered from Processed Meat.

| Isolate | Species | Vancomycin Resistance Gene Detected | Resistance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | Genotype | |||

| H1 | Enterococcus faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN CIP AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, erm(T), erm(B), dfrG |

| H2 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN AMP | aac(6’)-Ii, aadE, ant(9)-Ia, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, lnu(B), msr(C), cls, liaS, lsa(E), erm(B) |

| H3 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN AMP | aac(6’)-Ii, aadE, ant(9)-Ia, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, lnu(B), msr(C), cls, liaS, lsa(E), erm(B) |

| H4 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN CIP AMP | aac(6’)-Ii, aac(6’)-Ie-aph(2’’)-Ia, adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, liaS, erm(B), dfrG, dfrK |

| H6 | Enterococcus gallinarum | vanA, vanC1 | TET TEI VAN AMP ERY STR | aac(6’)-Ii, erm(B) |

| H7 | E. faecium | vanA | TET VAN AMP ERY CN K | aac(6’)-Ii, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, liaS, liaR, erm(B) |

| H8 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN CIP AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, erm(B) |

| A10 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, aadE, ant(9)-Ia, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, lnu(B), msr(C), cls, liaS, lsa(E), erm(B) |

| A11 | Enterococcus. durans | vanA | TET TEI VAN AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Iih, tet(L), tet(M), erm(B) |

| A12 | E. gallinarum | vanC1 | TEI VAN AMP ERY | ant(9)-Ia, msr(D), mef(A) |

| A13 | E. faecium | vanA | VAN CIP AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, erm(B) |

| A14 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, aadE, ant(9)-Ia, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, lnu(B), msr(C), cls, liaS, lsa(E), erm(B) |

| A16 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN CIP AMP ERY CN K | aac(6’)-Ii, adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, erm(B) |

| CP17 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, aadE, ant(9)-Ia, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, lnu(B), msr(C), cls, liaS, lsa(E), erm(B) |

| CP18 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, liaS, erm(B) |

| CP19 | E. faecium | vanA | TEI VAN CIP AMP ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, adeC, efmA, msr(C), cls, erm(B) |

| CP21 | E. faecium | vanA | TET TEI VAN ERY | aac(6’)-Ii, aadE, ant(9)-Ia, tet(L), tet(M), adeC, efmA, lnu(B), msr(C), cls, liaS, lsa(E), erm(B) |

| CP22 | E. durans | vanA | TET TEI VAN ERY | aac(6’)-Iih, tet(L), tet(M), erm(B) |

| CP23 | E. gallinarum | vanC1 | TET TEI VAN ERY | tet(L), tet(M) |

TET: tetracycline; TEI: teicoplanin; VAN: vancomycin; CIP: ciprofloxacin; AMP: ampicillin; ERY: erythromycin, STR: streptomycin; CN: gentamicin; K: kanamycin.

Regarding the genes that confer resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics, we identified the presence of the aac(6’)-Ii gene in all E. faecium isolates and in one E. gallinarum isolate (79%; n = 15/19), the ant(9)-Ia gene in six E. faecium isolates and in one E. gallinarum isolate (37%; n = 7/19), the aadE gene in six E. faecium isolates (32%; n = 6/19), the aac(6’)-Iih gene in only the E. durans isolates (11%; n = 2/19) and the aac(6’)-Ie-aph(2’’)-Ia gene in only one E. faecium isolate (5%; n = 1/19) (Table 1).

Several genes that confer resistance to macrolides were detected. We identified in most of the isolates the erm(B) gene (89%; n = 17/19). We also detected in one E. faecium isolate the erm(T) gene (5%; n = 1/19). Other macrolide resistance genes were detected, such as the lsa(E) gene in six E. faecium isolates (32%; n = 6/19), the mef(A) gene in only one E. gallinarum isolate (5%; n = 1/19), the msr(C) gene in all E. faecium isolates (74%; n = 14/19), and the msr(D) gene in only one E. gallinarum isolate (5%; n = 1/19) (Table 1).

We also detected one licosamide resistance gene, lnu(B), in six E. faecium isolates (32%; n = 6/19) (Table 1).

A combination of the tet(M) + tet(L) genes, conferring resistance to tetracycline, was found in all E. duran isolates, in nine E. faecium isolates, and in one E. gallinarum isolate (63%; n = 12/19) (Table 1).

Considering the lipopeptides class and the E. faecium species, since they were only detected in this species, the cls gene was present in all isolates (74%; n = 14/19), the liaS gene in nine isolates (47%; n = 9/19), and the liaR gene in only one isolate (5%; n = 1/19) (Table 1).

Some trimethoprim resistance genes were also detected, such as the dfrG gene in two E. faecium isolates (11%; n = 2/19) and the dfrK gene in one E. faecium isolate (5%; n = 1/19). We also identified two genes that are involved in efflux pump complexes, such as adeC (74%; n = 14/19) and efmA (74%; n = 14/19), present in all E. faecium isolates (Table 1).

3.4. Putative Biomarkers of Resistance Detection

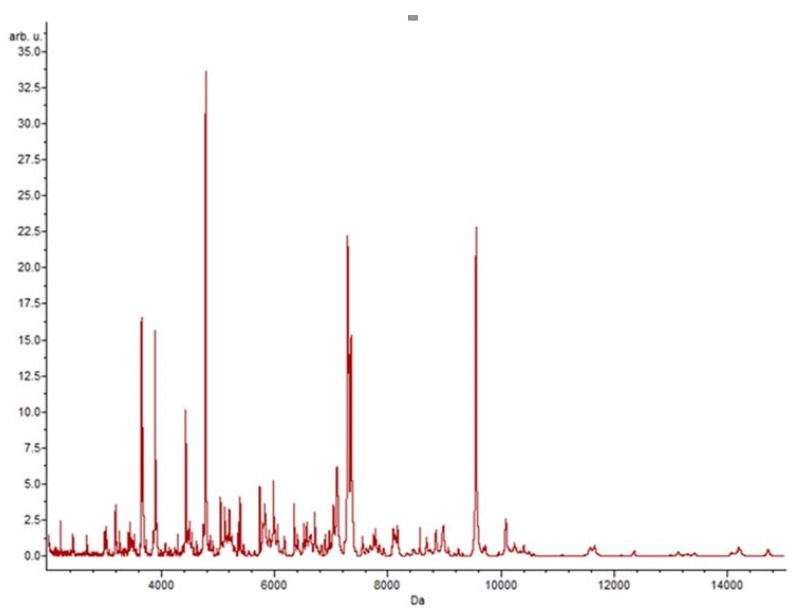

The aim of this approach was to observe the mass profiles of the resistance; therefore, an analysis was made using all isolates that showed resistance to a certain antibiotic. Data analysis was always done by comparing two classes: class 1 represents the isolates that grew in the absence of an antibiotic in the culture medium, and class 2 represents the isolates that grew in the presence of an antibiotic. After submission to the various classification algorithms, it was in the presence of erythromycin that more specific peaks were found (n = 28). In contrast, it was in the presence of ciprofloxacin that a lower number of specific peaks was detected (n = 11). Figure 1 shows the representative spectrum of the enterococci strains without antibiotic.

Figure 1.

Representative spectrum of Enterococcus spp. without antibiotic.

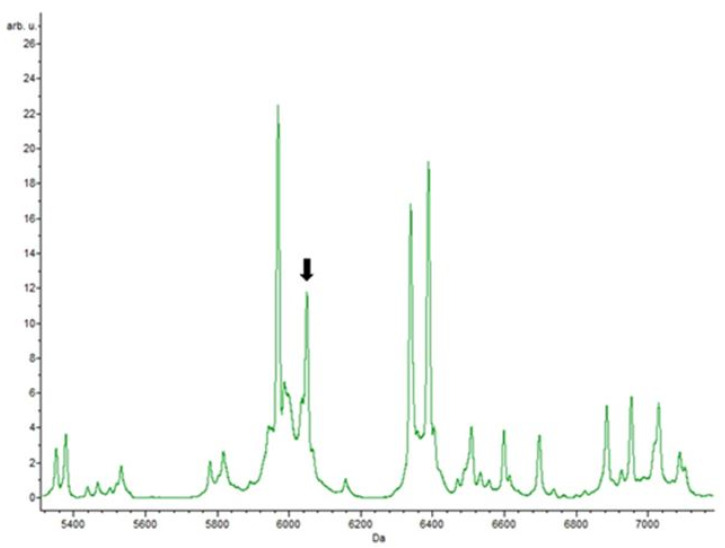

For all enterococci isolates, with and without antibiotics, a peak at m/z 4424.01 ± 3 was observed, representing a pertinent biomarker of the Enterococcus genus. A peak at m/z 6048 ± 1 was detected in all samples of E. faecium isolates, with a p-value of 0.00001, making this peak statistically significant and pointing to this as a putative biomarker of this species (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Enterococcus faecium spectrum showing the peak m/z 6048 ± 1 (p-value is 0.00001) characteristic of these strains.

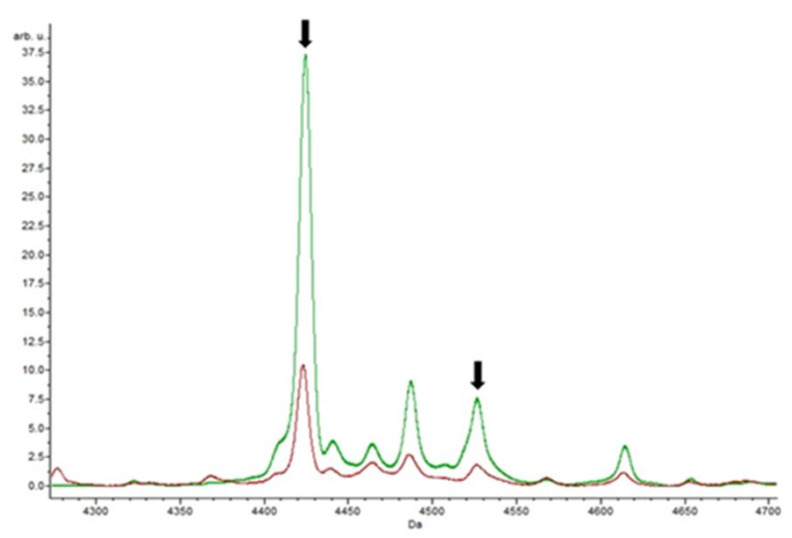

The eighteen isolates resistant to tetracycline were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS, and out of the 66 spectra analyzed, only 12 peaks were detected in at least one classification algorithm as potential biomarkers. Four of these peaks, m/z 2971.34, m/z 4424.01, m/z 4526.45, and m/z 6036.59, were recognized by two of the algorithms simultaneously. Figure 3 is a focus of the spectrum showing the masses m/z 4424.01 and m/z 4526.45.

Figure 3.

Peaks obtained for tetracycline. From the analysis of the ClinProTools software, the control spectrum without antibiotics (red) and the spectrum with the action of tetracycline (green) were obtained. The results show statistically significant peaks, with a p-value of 0.0000001, such as masses m/z 4424.01 and m/z 4526.45 noted by arrows.

The peak at m/z 6036.59 was exclusively detected in the isolates resistant to tetracycline. The specificity of this peak, regarding the antibiotic, may indicate a potential biomarker of resistance. In contrast, the peak at m/z 4526.45 ± 1 was also identified in the isolates resistant to erythromycin, and the peak at m/z 2971.34 ± 1 in the isolates resistant to teicoplanin and erythromycin.

Relative to the isolates resistant to erythromycin, the peak that stood out the most, of a total of 165 peaks detected, was at m/z 4423.39, since all classification algorithms detected it and the AUC value was 0.92. Four unique peaks were also identified, m/z 3289.2, 5951.28, m/z 6387.81, and m/z 6926.39, with great intensity relative to the control isolates.

In a model generation of each algorithm, there was a model internally validated by cross-validation. Herewith, the validation values for the model correspond to 97.77% for the genetic algorithm, 90.04% for the supervised neural network and 87.32% for the QuickClassifier, which proves the accuracy of the peaks obtained for erythromycin.

Of the 21 peaks detected in the isolates resistant to teicoplanin, only five of them were considered putative biomarkers as shown in Table S1. Two of them were found in the three classification algorithms, and the other three peaks were only detected by two classification algorithms (Table S1).

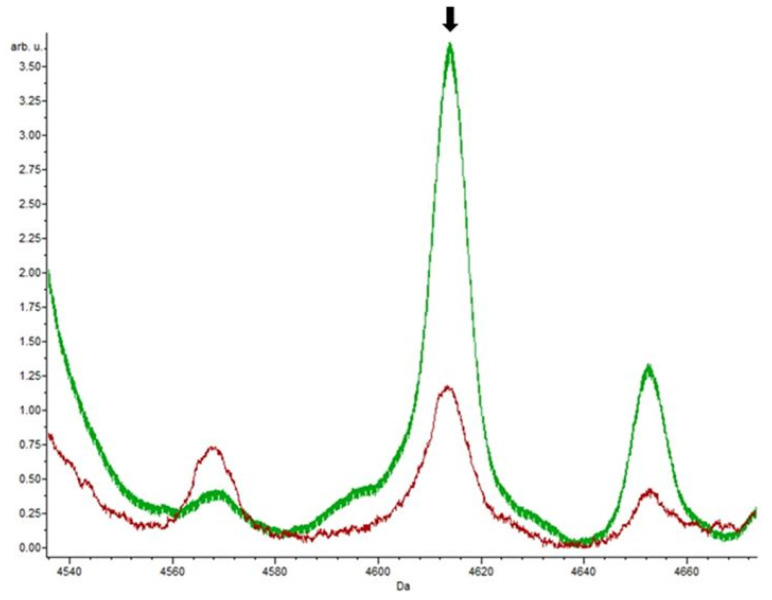

Furthermore, the peaks at m/z 2153.18, m/z 4227.42, and m/z 4652.66 were not detected simultaneously by the three classification algorithms; however, they can be used as biomarkers of resistance since they were only identified in isolates resistant to this antibiotic. Nevertheless, the values of the AUC curve were not as significant (0.63, 0.71, and 0.54, respectively), which means these peaks can be false positives. Figure 4 focuses on the part of the spectrum highlighting the peak at m/z 4652.66.

Figure 4.

The red spectrum represents the control and the green spectrum was obtained by the action of teicoplanin. The arrow shows a peak at m/z 4652.66 with greater intensity in the presence of the antibiotic.

None of the peaks detected in the isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin was identified by more than one classification algorithm. However, the cross validation in the model generation was 94.74% for the genetic algorithm, 60.09% for the supervised neural network, and 87.03% for the QuickClassifier, demonstrating that although the peaks were only found by one of them, the peaks obtained were accurately detected. This result may be due to the fact that the total number of analyzed spectra was lower (n = 24) than in isolates resistant to other antibiotics.

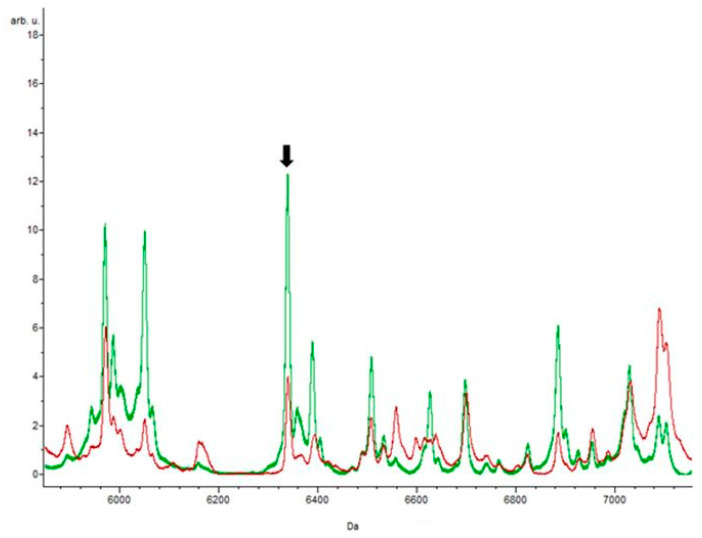

The peaks at m/z 6358.27 and m/z 13237.3, with a p-value of 0.0000001, were only present in the isolates resistant to this antibiotic, indicating potential biomarkers. The peak at m/z 6358.27 appeared in isolates stressed with ciprofloxacin, with great intensity, suggesting that it is a protein underlying this resistance mechanism since it was absent in the control (Figure 5). In contrast, in relation to the control, the peak at m/z 13237.3 decreased in intensity.

Figure 5.

The red spectrum represents the control, and the green spectrum was obtained by the action of ciprofloxacin. The arrow shows the peak at m/z 4652.66 with greater intensity in the presence of the antibiotic. Among the 27 specific peaks detected in the isolates resistant to ampicillin, only the peak with mass m/z 6338 was identified by the three classification algorithms, with an area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.89. This peak was also identified in erythromycin-resistant isolates. In contrast, three other peaks, m/z 2361.38, m/z 3304.92, and m/z 7240.29, proved to be exclusive to these isolates, which means they are potential biomarkers of ampicillin resistance.

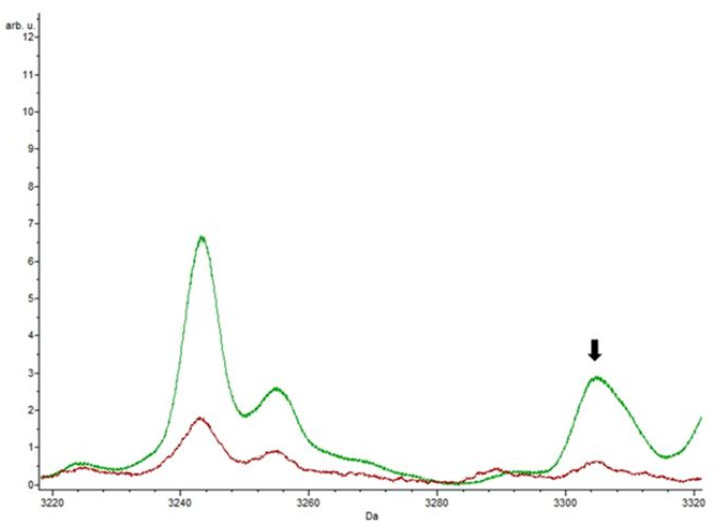

Figure 6 focuses on the part of the spectrum highlighting the peak at m/z 3304.92.

Figure 6.

The red spectrum represents the control, and the green spectrum was obtained by the action of ampicillin. The arrow shows the peak at m/z 3304.92 that was only detected in the presence of the antibiotic.

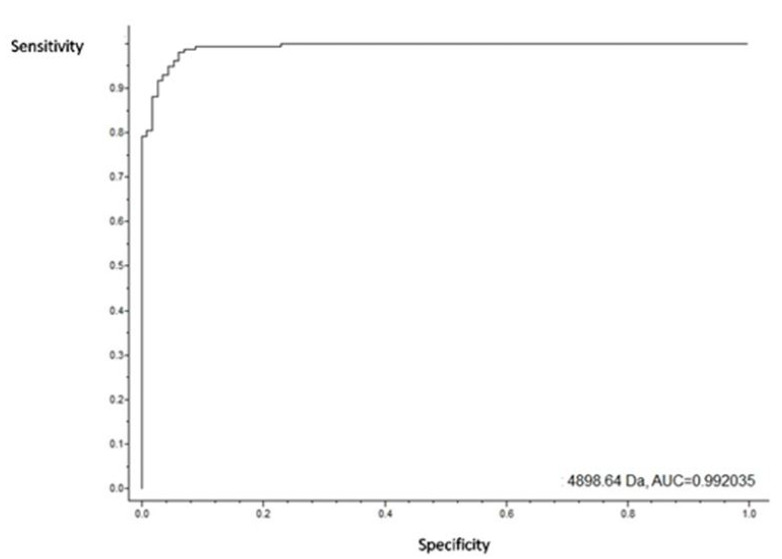

It was among the isolates resistant to vancomycin that the greatest number of peaks was detected, about twenty-five. The peak at m/z 4898.64 was shown to have the highest AUC value (0.99) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

AUC value for the peak at m/z 4898.64. The value of the area under the ROC curve is 0.99, indicating a high-test pass for detecting the peak at m/z 4898.64.

The peak at m/z 4898.64 appeared in all antibiotics except the teicoplanin antibiotic, referring to the absence of the protein in the specific resistance mechanism of this antibiotic. The cross validation in the model generation was 97.61% for the genetic algorithm, 96.65% for the supervised neural network, and 94.48% for the QuickClassifier, proving the efficiency of our model regarding the analysis of the isolates resistant to this antibiotic. It was also found that the peaks at m/z 2263.54 and m/z 7610.17 were only present when these bacteria were stressed with vancomycin. The peak at m/z 2263.54 showed an increase in the intensity relative to the control isolates, which proves that this peak is a potential biomarker of vancomycin resistance.

The masses m/z 3255.03, m/z 3454.55, m/z 3665.36, m/z 5352.64, m/z 5988.57, m/z 8738.67, m/z 9234.06, m/z 9950.35, m/z 10072.31, m/z 10224.25, m/z 12209.66, and m/z 12983.05 were detected in isolates resistant to vancomycin, but also in the control isolates. The peaks at m/z 3255.03, m/z 3665.26, and m/z 5352.64 increased in intensity relative to control isolates, while the remaining peaks decreased in intensity, which may indicate that these peaks are potential vancomycin resistance biomarkers.

4. Discussion

Currently, the detection of Enterococcus spp. resistant to vancomycin is generally considered an epidemiological problem since they mostly reside in the human gastrointestinal tract and can persevere in hospital environments. Colonization with VRE generally precedes infection [35]. Interest in the detection of VRE has been increasing [36], given the global relevance of the problem. In Portugal, this resistance has been reported in several environments, with special incidence in wild animals from our research group [37,38,39,40].

Interestingly, the species Enterococcus faecalis was not identified among the VRE strains. This result is in accordance with other studies carried out in animal-originated food [41,42,43]. In contrast, the presence of E. faecalis was reported by researchers in samples of meat in Tunisia [44] and other food products of animal origin in Turkey [45]. The predominant species of enterococci in the processed meat samples used in this study was E. faecium. This fact is corroborated by data previously reported for chicken meat, different types of meat, and ready-to-eat seafood [42,46,47].

All VRE isolates presented a phenotype of multi-resistance, where 17 isolates showed resistance to teicoplanin, 16 isolates to erythromycin and tetracycline, and 14 isolates to ampicillin. The high use of these antibiotics, particularly erythromycin, in human and animal medicine, may explain the increasing level of resistance [5,48]. Ciprofloxacin resistance had low incidence, similar to other studies [49]. The fact that fewer isolates showed resistance to ciprofloxacin when compared to the antibiotics mentioned above can be explained by its moderate activity on enterococci [50].

High-level resistance to aminoglycosides was also identified: gentamicin (n = 2), kanamycin (n = 2), and streptomycin (n = 1). Another study also detected VRE isolates that showed high-level resistance to aminoglycosides; however, the resistances were only for kanamycin and streptomycin [48]. Additionally, all isolates from this study, similar to many other clinical isolates from other studies, remained susceptible to chloramphenicol [51,52,53]. This susceptibility can be explained by the availability of specific therapies that make the clinical use of this antibiotic less common [54]. The species E. faecium showed phenotypic resistance to most of the antibiotics under study, with 12 isolates resistant to tetracycline, 11 isolates to erythromycin, six isolates to ciprofloxacin, and two isolates with high-level resistance against aminoglycosides. E. durans was shown to be resistant to erythromycin, tetracycline, and ampicillin. Although E. durans is one of the species causing the lowest percentage of infections [55], this species has been achieving a level of resistance compared to E. faecium, which leads to considering this risk, apparently smaller, more concerning. The E. gallinarum species showed resistance to antibiotics such as erythromycin, tetracycline, and ampicillin. One of the isolates (H6) also showed a high level of resistance to streptomycin. The presence of vancomycin resistance in E. gallinarum was expected since this species was identified by the presence of the vanC1 gene, which confers a low level of intrinsic resistance to this antibiotic. Similar to E. durans, the presence of high levels of antibiotic resistance makes E. gallinarum a target of attention.

With respect to the resistance genes obtained from Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), in this study we detected a wide variety of genes conferring resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents.

Vancomycin and ampicillin resistance is among the most common and problematic resistance in enterococci, especially in E. faecium. While the vanA and vanB genes, associated with vancomycin resistance, are considered clinically relevant in E. faecium and E. faecalis, the vanC1 gene is an intrinsic gene of E. gallinarum [54]. The detection of vanA and vanC1 genes in this study confirms the presence of VRE among our processed meat isolates, corroborating, in this way, our phenotypic results. Most vanA-positive isolates were E. faecium; however, this gene was also detected in E. durans isolates and, interestingly, in one E. gallinarum isolate. Similarly, in a study carried out on raw meat products in Italy, the presence of a vanA + vanC1 combination in one E. gallinarum isolate was also reported [56]. These results suggest that not only E. faecium, but also other vanA-positive enterococci, are present in meat products and are potentially capable of disseminating to humans.

The most prevalent aminoglycoside resistance gene among our isolates was aac(6’)-Ii (79%). In a study carried out on enterococci isolated from bird carcasses, the presence of aac(6’)-Ii was detected in most isolates (32%) [57]. We identified one isolate that harbored the aac(6’)-Ie-aph(2’’)-Ia gene and six isolates that harbored the aadE gene, as other researchers did in a comparative study between isolates from humans, pigs, and pork where they also detected these two genes in E. faecium and in E. faecalis [58]. We also detected two more genes that confer resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics, namely, aac(6’)-Iih and ant(9)-Ia. A study carried out in bovine feces also reported the presence of the aac(6’)-Iih gene in 10 isolates of E. hirae, whereas in our study it was found in E. durans, and the ant(9)-Ia gene was found in only one isolate of E. faecium in the same way as in our study [59].

Resistance to macrolide antimicrobials was confirmed mostly by the presence of erm(B) genes; however, we also detected other genes, namely, erm(T), msr(C), lsa(E), mef(A), and msr(D). Other studies also reported the presence of these genes among samples isolated from meat in Tunisia [43] and in fecal samples from animals for consumption, such as cattle and pigs [59,60]. Although these studies were not carried out on meat, it is also important to underline that these animals will serve as food for humans and will possibly transmit this resistance.

Other genes were detected in this work, such as lnu(B), msr(C), msr(D), cls, liaS, liaR, dfrG, dfrK, efmA, and adeC. Other researchers also detected the presence of some of these genes in enterococci, for example, Cavaco and his collaborators, in 2017, reported the presence of lnu(B) and msr(C) genes among E. faecalis isolates [61]; López along with colleagues, reported in 2012 the presence of dfrG and dfrK genes in enterococci isolates [62]; Beukers and collaborators, in 2017, detected the presence of the adeC gene among E. faecium isolates [59]; and cls, liaS, and liaR were detected by Lellek and colleagues in 2015, also among E. faecium isolates [63].

The genes found in our NGS analysis agreed with some the resistance phenotypes observed. However, in some isolates, we identified the resistance phenotype but no resistance gene, and in others we verified that in some isolates we detected resistance genes but no resistance phenotypes. Nevertheless, there is not always a correlation between phenotype and genotype. Sometimes, the susceptibility to antibiotics is highly dependent on the bacterial metabolism, and the global metabolic regulators that modulate this phenotype or resistance genes may not be expressed [64].

These results indicate that consumers are exposed to VREs from various animal-origin foods. This can be directly through the consumption of contaminated food or indirectly through cross-contamination with other foods during processing.

Considering the detection of resistance biomarkers, for the aminoglycoside antibiotics class, it was not possible to carry out the MALDI-TOF MS analysis, since the number of isolates resistant to this antibiotics class did not indicate a statistically significant result.

In this work there were masses detected by the different classification algorithms that were present in different antibiotics. Possibly, these masses corresponded to basal proteins of the bacteria, since they were present in isolates resistant to different antibiotic classes [25]. All peaks detected for the genus (m/z 4424.01 ± 3) and E. faecium (m/z 6048 ± 1) were in accordance with those reported in the literature, representing a good biomarker [65,66].

In a previous study on MRSA, it was observed that masses below m/z 2400 were more intense in MRSA susceptible to teicoplanin compared to MRSA resistant to teicoplanin [67]. The results obtained in this work are in accordance with this study about teicoplanin, since only two peaks with a mass below this value were detected in our teicoplanin-resistant isolates.

A study carried out in 2012 by Griffin, aiming to determine the difference between the masses of vanA and vanB genes. A peak at m/z 6603.51 was observed more intensely in vanA compared to vanB [68]. In our study on vancomycin, as the vanB gene was not present, we were unable to make this distinction.

Many of the peaks obtained, although not exclusive, are considered good putative biomarkers because there are significant variations, either due to the increase or decrease in the intensity of the peaks, relative to control isolates. For the remaining peaks detected in the isolates resistant to the different antibiotics, there are not many studies that helped us to prove that the putative biomarkers in this work are indicators of resistance biomarkers, which makes this work a good starting point for other researchers. Biomarkers would be of utmost importance to detect antibiotic-resistant bacteria from any reservoir, which could make the use of biomarkers promising in the context of studies on One Health.

5. Conclusions

This study confirmed the existence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci strains of different species in processed meat samples. Several studies have reported the reality of this problem in animal production; however, this study confirms the presence and dissemination of these microorganisms in human food. The isolates under study showed multi-resistance to antibiotics in addition to being vancomycin resistant.

The results obtained from advanced techniques, such as next-generation sequencing, suggest that meat plays a potential role as a reservoir of resistance genes, triggering the need to carry out more studies to evaluate the mobility of these genes. MALDI-TOF MS demonstrated high potential for the identification of putative biomarkers of resistance to different antibiotics. Thus, the consumption of contaminated meat may be associated with the spread and colonization of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in humans and for this reason, could represent a public health concern.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/9/5/89/s1, Table S1: Exclusive masses found for each antibiotic.

Author Contributions

C.S. and T.d.S. contributed equally to the manuscript. C.S., T.d.S., and S.O. developed the experimental idea, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. The final version was written with contributions from all authors. D.V., L.T., C.C., and M.H. conducted the assays for proteomic evaluation. R.B. (Racha Beyrouthy) and R.B. (Richard Bonnet) conducted the NGS tasks. M.C. and G.I. prepared the published work. P.P. was responsible for the provision of study materials. P.P. and G.I. conceived the experimental design and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Espectrometria de massa e sequenciação aplicadas à microbiologia clínica moderna: pesquisa e identificação de biomarcadores em espécies bacterianas multiresistentes” (Programa de Acções Universitárias Integradas Luso-Francesas, Ação n.º: TC-14 / 2017) and by the Associate Laboratory for Green Chemistry, LAQV, which is financed by national funds from FCT/MCTES (UID/QUI/50006/2020). The authors are grateful for the support of UIDB/00211/2020 funded by FCT/MCTES through national funds. We also thank the Ministere de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Superieur et de la Recherche, INSERM (UMR1071), INRA (USC-2018), Santé Publique France, and the Centre Hospitalier Regional Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Lebreton F., Willems R.J.L., Gilmore M.S. Enterococcus Diversity, Origins in Nature, and Gut Colonization. In: Gilmore M.S., Clewell D.B., Ike Y., Shankar N., editors. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; Boston, MA, USA: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepard B.D., Gilmore M.S. Antibiotic-resistant enterococci: the mechanisms and dynamics of drug introduction and resistance. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:215–224. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonçalves A., Poeta P., Silva N., Araújo C., Lopez M., Ruiz E., Uliyakina I., Direitinho J., Igrejas G., Torres C. Characterization of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Fecal Samples of Ostriches by Molecular Methods. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010;7:1133–1136. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias C.A., Murray B.E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poeta P., Costa D., Igrejas G., Rodrigues J., Torres C. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in faecal enterococci from wild boars (Sus scrofa) Vet. Microbiol. 2007;125:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Boeckel T.P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B.T., Levin S.A., Robinson T.P., Teillant A., Laxminarayan R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landers T., Cohen B., Wittum T.E., Larson E.L. A Review of Antibiotic Use in Food Animals: Perspective, Policy, and Potential. Public Heal. Rep. 2012;127:4–22. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhavnani S.M., Drake J.A., Forrest A., Deinhart J.A., Jones R.N., Biedenbach D.J., Ballow C.H. A nationwide, multicenter, case-control study comparing risk factors, treatment, and outcome for vancomycin-resistant and -susceptible enterococcal bacteremia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2000;36:145–158. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(99)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taji A., Heidari H., Ebrahim-Saraie H.S., Sarvari J., Motamedifar M. High prevalence of vancomycin and high-level gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis isolates. Acta Microbiol. et Immunol. Hung. 2019;66:203–217. doi: 10.1556/030.65.2018.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed M.O., Baptiste K.E. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci: A Review of Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Perspectives of Human and Animal Health. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018;24:590–606. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zalipour M., Esfahani B.N., Havaei S.A. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of glycopeptide, aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance among clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis: a multicenter based study. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12:292. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arthur M., Molinas C., Depardieu F., Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:117–127. doi: 10.1128/JB.175.1.117-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chotinantakul K., Chansiw N., Okada S. Antimicrobial resistance of Enterococcus spp. isolated from Thai fermented pork in Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018;12:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahan M., Zhanel G.G., Sparling R., Holley R.A. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance from Enterococcus faecium of fermented meat origin to clinical isolates of E. faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015;199:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vakulenko S.B., Donabedian S.M., Voskresenskiy A.M., Zervos M.J., Lerner S.A., Chow J. Multiplex PCR for Detection of Aminoglycoside Resistance Genes in Enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1423–1426. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1423-1426.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdelkareem M.Z., Sayed M., Hassuna N.A., Mahmoud M.S., Abdelwahab S.F. Multi-drug-resistant Enterococcus faecalisamong Egyptian patients with urinary tract infection. J. Chemother. 2016;29:74–82. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2016.1182358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chouchani C., El Salabi A., Marrakchi R., Ferchichi L., Walsh T.R. First report of mefA and msrA/msrB multidrug efflux pumps associated with blaTEM-1 β-lactamase in Enterococcus faecalis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;16:e104–e109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jungblut P.R., Holzhütter H.-G., Apweiler R., Schlüter H. The speciation of the proteome. Chem. Central J. 2008;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radhouani H., Pinto L., Poeta P., Igrejas G. After genomics, what proteomics tools could help us understand the antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli? J. Proteom. 2012;75:2773–2789. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolters M., Rohde H., Maier T., Belmar-Campos C., Franke G., Scherpe S., Aepfelbacher M., Christner M. MALDI-TOF MS fingerprinting allows for discrimination of major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 2011;301:64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei W., Li-Jun W., Sui W., Gui Z., Xin-Xin L. Application of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry in the Screening of VanA-Positive Enterococcus Faecium. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014;20:461–465. doi: 10.1255/ejms.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Croxatto A., Prod’Hom G., Greub G. Applications of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in clinical diagnostic microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012;36:380–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigdel T.K., Sarwal M.M. The proteogenomic path towards biomarker discovery. Pediatr. Transplant. 2008;12:737–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.01018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veenstra T.D. Global and targeted quantitative proteomics for biomarker discovery. J. Chromatogr. B. 2007;847:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J.-M., Han J.J., Altwerger G., Kohn E.C. Proteomics and biomarkers in clinical trials for drug development. J. Proteom. 2011;74:2632–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balouiri M., Sadiki M., Ibnsouda S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2015;6:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornsberry C. NCCLS Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests. Lab. Med. 1983;14:549–553. doi: 10.1093/labmed/14.9.549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nurk S., Bankevich A., Antipov D., Gurevich A., Korobeynikov A., Lapidus A., Prjibelski A.D., Pyshkin A., Sirotkin A., Sirotkin Y., et al. Assembling Single-Cell Genomes and Mini-Metagenomes From Chimeric MDA Products. J. Comput. Boil. 2013;20:714–737. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2013.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinform. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker B.J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., Cuomo C.A., Zeng Q., Wortman J., Young S.K., et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt M., Mather A.E., Sánchez-Busó L., Page A.J., Parkhill J., Keane J.A., Harris S.R. ARIBA: Rapid antimicrobial resistance genotyping directly from sequencing reads. Microb. Genomics. 2017;3:e000131. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia B., Raphenya A.R., Alcock B., Waglechner N., Guo P., Tsang K.K., Lago B.A., Dave B.M., Pereira S., Sharma A.N., et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45:D566–D573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., Aarestrup F.M., Larsen M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freiwald A., Sauer S. Phylogenetic classification and identification of bacteria by mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:732–742. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reyes K., Bardossy A.C., Zervos M. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2016;30:953–965. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristich C.J., Rice L.B., Arias C.A. Enterococcal Infection-Treatment and Antibiotic Resistance. In: Gilmore M.S., Clewell D.B., Ike Y., Shankar N., editors. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; Boston, MA, USA: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barros J., Andrade M., Radhouani H., Lopez M., Igrejas G., Poeta P., Torres C. Detection of vanA-Containing Enterococcus Species in Faecal Microbiota of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata) Microbes Environ. 2012;27:509–511. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME11346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonçalves A., Igrejas G., Radhouani H., Correia S., Pacheco R., Santos T., Monteiro R., Guerra A., Petrucci-Fonseca F., Brito F., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in faecal enterococci and Escherichia coli isolates recovered from Iberian wolf. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;56:268–274. doi: 10.1111/lam.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marinho C.M., Silva N., Pombo S., Santos T., Monteiro R., Gonçalves A., Micael J., Rodrigues P., Costa A., Igrejas G., et al. Echinoderms from Azores islands: An unexpected source of antibiotic resistant Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli isolates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013;69:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poeta P., Radhouani H., Igrejas G., Gonçalves A., Carvalho C., Rodrigues J., Vinué L., Somalo S., Torres C. Seagulls of the Berlengas Natural Reserve of Portugal as Carriers of Fecal Escherichia coli Harboring CTX-M and TEM Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:7439–7441. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00949-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cetinkaya F., Mus T.E., Soyutemiz G.E., Cibik R. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in animal originated foods. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2013;37:588–593. doi: 10.3906/vet-1211-34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guerrero-Ramos E., Molina D., Blanco-Morán S., Igrejas G., Poeta P., Alonso-Calleja C., Capita R. Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Genotypic Characterization of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Meat Preparations. J. Food Prot. 2016;79:748–756. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jung W.K., Lim J.Y., Kwon N.H., Kim J.M., Hong S.K., Koo H.C., Kim S.H., Park Y.H. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci from animal sources in Korea. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;113:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klibi N., Ben Said L., Jouini A., Ben Slama K., Lopez M., Ben Sallem R., Boudabous A., Torres C. Species distribution, antibiotic resistance and virulence traits in enterococci from meat in Tunisia. Meat Sci. 2013;93:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mus T.E., Cetinkaya F., Cibik R., Soyutemiz G.E., Simsek H., Coplu N. Pathogenicity determinants and antibiotic resistance profiles of enterococci from foods of animal origin in Turkey. Acta Veter- Hung. 2017;65:461–474. doi: 10.1556/004.2017.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Igbinosa E.O., Beshiru A. Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence Determinants, and Biofilm Formation of Enterococcus Species From Ready-to-Eat Seafood. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:728. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zarfel G., Galler H., Luxner J., Petternel C., Reinthaler F.F., Haas D., Kittinger C., Grisold A., Pless P., Feierl G. Multiresistant Bacteria Isolated from Chicken Meat in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2014;11:12582–12593. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111212582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayes J.R., English L.L., Carter P.J., Proescholdt T., Lee K.Y., Wagner D.D., White D.G. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Retail Meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:7153–7160. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7153-7160.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poeta P., Costa D., Rodrigues J., Torres C. Study of faecal colonization by vanA-containing Enterococcus strains in healthy humans, pets, poultry and wild animals in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;55:278–280. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez-Guerrero M., Rouse M.S., Henry N.K., E Geraci J., Wilson W.R. In vitro and in vivo activity of ciprofloxacin against enterococci isolated from patients with infective endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987;31:430–433. doi: 10.1128/AAC.31.3.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deshpande L.M., Fritsche T.R., Moet G.J., Biedenbach D.J., Jones R.N. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from North America and Europe: a report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007;58:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lautenbach E., Gould C.V., A LaRosa L., Marr A.M., Nachamkin I., Bilker W.B., O Fishman N. Emergence of resistance to chloramphenicol among vancomycin-resistant enterococcal (VRE) bloodstream isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2004;23:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lautenbach E., Schuster M.G., Bilker W.B., Brennan P.J. The role of chloramphenicol in the treatment of bloodstream infection due to vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998;27:1259–1265. doi: 10.1086/515002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel G., Snydman D.R. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Infections in Solid Organ Transplantation. Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2013;13:59–67. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patterson J.E., Sweeney A.H., Simms M., Carley N., Mangi R., Sabetta J., Lyons R.W. An Analysis of 110 Serious Enterococcal Infections Epidemiology, Antibiotic Susceptibility, and Outcome. Med. 1995;74:191–200. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Del Grosso M., Caprioli A., Chinzari P., Fontana M.C., Pezzotti G., Manfrin A., Di Giannatale E., Goffredo E., Pantosti A. Detection and Characterization of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Farm Animals and Raw Meat Products in Italy. Microb. Drug Resist. 2000;6:313–318. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2000.6.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson C.R., Fedorka-Cray P., Barrett J.B., Ladely S.R. Genetic Relatedness of High-Level Aminoglycoside-Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Poultry Carcasses. Avian Dis. 2004;48:100–107. doi: 10.1637/7071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thu W.P., Sinwat N., Bitrus A.A., Angkittitrakul S., Prathan R., Chuanchuen R. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene, and class 1 integrons of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis from pigs, pork and humans in Thai-Laos border provinces. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019;18:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beukers A.G., Zaheer R., Goji N., Amoako K.K., Chaves A.V., Ward M., McAllister T.A. Comparative genomics of Enterococcus spp. isolated from bovine feces. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17:52. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-0962-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li X.-S., Dong W.-C., Wang X.-M., Hu G.-Z., Cai B.-Y., Wu C.-M., Du X.-D. Presence and genetic environment of pleuromutilin-lincosamide-streptogramin A resistance gene lsa(E) in enterococci of human and swine origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013;69:1424–1426. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cavaco L., Bernal J.F., Zankari E., Léon M., Hendriksen R., Perez-Gutierrez E., Aarestrup F.M., Donado-Godoy P. Detection of linezolid resistance due to the optrA gene in Enterococcus faecalis from poultry meat from the American continent (Colombia) J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;72:678–683. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopez M., Kadlec K., Schwarz S., Torres C. First Detection of the Staphylococcal Trimethoprim Resistance GenedfrKand thedfrK-Carrying Transposon Tn559in Enterococci. Microb. Drug Resist. 2012;18:13–18. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2011.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lellek H., Franke G.C., Ruckert C., Wolters M., Wolschke C., Christner M., Büttner H., Alawi M., Kröger N., Rohde H. Emergence of daptomycin non-susceptibility in colonizing vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates during daptomycin therapy. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 2015;305:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corona F., Martínez J.L. Phenotypic Resistance to Antibiotics. Antibiotics. 2013;2:237–255. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2020237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quintela-Baluja M., Böhme K., Fernández-No I.C., Morandi S., Alnakip M., Caamaño-Antelo S., Velázquez J.B., Calo-Mata P. Characterization of different food-isolated Enterococcus strains by MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting. Electrophor. 2013;34:2240–2250. doi: 10.1002/elps.201200699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Santos T.J.B. Ph.D. Thesis. Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro; Vila Real, Portugal: 2014. Proteogenómica de isolados de Enterococcus spp. e Escherichia coli com a utilização do MALDI-TOF MS. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- 67.A Majcherczyk P., McKenna T., Moreillon P., Vaudaux P. The discriminatory power of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to differentiate between isogenic teicoplanin-susceptible and teicoplanin-resistant strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006;255:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Griffin P., Price G., Schooneveldt J.M., Schlebusch S., Tilse M.H., Urbanski T., Hamilton B.R., Venter D. Use of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry To Identify Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci and Investigate the Epidemiology of an Outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:2918–2931. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01000-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.