Abstract

Background:

Although vitamin D inhibits breast tumor growth in experimental settings, the findings from population-based studies remain inconclusive. Our goals were to investigate the association between pre-diagnostic plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration and breast cancer recurrence in prospective epidemiological studies and to explore the molecular underpinnings linking 25(OH)D to slower progression of breast cancer in the Nurses’ Health Studies (N=659).

Methods:

Plasma 25(OH)D was measured with a high-affinity-protein-binding-assay/a radioimmunoassay. We profiled transcriptome-wide-gene-expression in breast tumors using microarrays. Hazard ratios (HRs) of breast cancer recurrence were estimated from covariate-adjusted-Cox-regressions. We examined differential gene expression in association with 25(OH)D and employed pathway analysis. We derived a gene expression score for 25(OH)D, and assessed associations between the score and cancer recurrence.

Results:

Although 25(OH)D was not associated with breast cancer recurrence overall (HR=0.97; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.88–1.08), the association varied by estrogen-receptor (ER) status (p-for-interaction=0.005). Importantly, among ER-positive stage I-to-III cancers, every 5ng/ml increase in 25(OH)D was associated with a 13% lower risk of recurrence (HR=0.87; 95%-CI: 0.76–0.99). A null association was observed for ER-negative cancers (HR=1.07; 95% CI: 0.91; 1.27). Pathway analysis identified multiple gene-sets that were significantly (FDR<5%) down-regulated in ER-positive tumors of women with high 25(OH)D (≥30ng/ml), compared to those with low levels (<30ng/ml). These gene-sets are primarily involved in tumor proliferation, migration, and inflammation. 25(OH)D score derived from these gene-sets was marginally associated with reduced risk of recurrence in ER-positive diseases (HR=0.77; 95%-CI: 0.59–1.01) in the NHS studies, however, no association was noted in METABRIC, suggesting that further refinement is need to improve the generalizability of the score.

Conclusions:

Our findings support an intriguing line of research for studies to better understand the mechanisms underlying the role of vitamin D in breast tumor progression, particularly for the ER-positive subtype.

Impact:

Vitamin D may present a personal-level secondary-prevention strategy for ER-positive breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D is a multifunctional steroid hormone that can be synthesized cutaneously from 7-dehydrocholesterol in response to sun exposure or obtained from natural and fortified foods and supplements1,2. Vitamin D undergoes two hydroxylation steps in its activation path to the active hormone, first converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) in the liver and ultimately to calcitrol (1α,25(OH)2D)—the most biologically active form of vitamin D1,2. Although 1α-hydroxylation primarily takes place in the kidney, it also occurs in many, if not most, extra-renal sites such as the breast and breast cancer cells, where vitamin D signal transduction is also modulated in an paracrine or an autocrine manner in non-skeletal sites mediating non-calcium related actions1,2. In all target cells, 1α,25(OH)2D forms a ligand-bound complex with the vitamin D receptor (VDR)—retinoid X receptor (RXR) heterodimer, and together with other co-modulators binds to vitamin D response elements (VDREs) to initiate transcriptional cascades that stimulate or reduce selective genes that mediate the actions of the hormone1–4.

Despite long-standing knowledge of its role in bone mineralization and calcium homoeostasis, compelling experimental studies showed that vitamin D and its analogs exhibit anti-carcinogenic properties and can regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, inflammation, invasion and metastasis in breast tumors5–7. In vitro and in vivo studies also showed that vitamin D can potentiate the anti-carcinogenic effects of chemotherapeutic agents in tumors8–10. However, in prospective population-based studies and randomized clinical trials, the association between pre-diagnostic vitamin D levels with breast cancer survival remains inconclusive. While several meta-analyses showed statistically significant associations between 25(OH)D and improved survival among breast cancer patients11–19, a recent large-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed no clear benefit of high-dose vitamin D (2,000 IU/day) on breast cancer specific mortality over a five-year follow-up20. A better understanding of the molecular mechanisms linking pre-diagnostic vitamin D concentration with breast cancer recurrence would provide important human evidence supporting the role of vitamin D in preventing tumor progression and thereby improving survival.

To assess the potential prognostic effects of vitamin D, we prospectively evaluated the association between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D with breast cancer recurrence from invasive breast cancer cases drawn from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHSII. We next sought to explore molecular underpinnings of 25(OH)D associated gene expression regulation for breast tumor progression using transcriptome-wide profiling. Since our previous work showed that post-diagnosis vitamin D supplement use was only associated with decreased risk of recurrence among ER-positive, but not ER-negative breast cancer21, we will examine the associations also by ER status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This study includes participants from two large-scale prospective longitudinal cohorts of registered female nurses in the U.S.—the NHS and the NHSII. Established in 1976, the NHS recruited 121,701 women, aged 30–55 years, who completed and returned an initial questionnaire. In 1989, the NHSII was initiated, which enrolled 116,429 women, ages 25–42 years, who completed and returned an initial questionnaire. Both cohorts followed participants via questionnaires mailed biennially to update information on lifestyles, medications and ascertain outcomes. The cumulative follow-up rates were greater than 90% for the NHS and NHSII22. Invasive breast cancer cases were initially identified by participants’ responses to the biennial questionnaires from the start of follow-up to 2012, or through searching the National Death Index for participants who did not respond. With participants’ permission, we were able to link 96% of breast cancer cases to relevant medical records. Using established protocols, centralized medical record review confirmed over 99% of reported breast cancer cases. All breast cancer cases included in this analysis had no reported previous history of cancer. In 1993, we started to collect archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded breast cancer blocks for participants with primary incident breast cancer and were able to create tissue microarrays (TMAs) from 5561 NHS and NHSII participants (Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Tissue Microarray Core Facility, Boston, MA). Given limited funds, we prioritized women with existing genetic and circulating biomarker measurements, and were able to perform tumor tissue gene expression microarrays for 954 breast cancer cases. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required.

Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D measurements

Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D levels were measured in nested case-control studies of breast cancer in six batches, as published previously23–25. In brief, 25(OH)D levels were measured using either a high-affinity protein binding assay (Dr. Michael F. Holick laboratory, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA or Dr. Bruce W. Hollis laboratory, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) and a radioimmunoassay with radioiodinate tracers (Heartland Assays, Inc. Ames, IA, USA). Neither assay could distinguish between 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 and therefore we use the term 25(OH)D without subscript to connote total circulating vitamin D2 and D3 metabolites. Coefficients of variances (CVs) ranged from 6.0% to 17.6% for blinded quality control samples in each batch23–25. We controlled for potential batch effects by recalibrating 25(OH)D distribution for each batch to an “average” batch, independent of age, body mass index (BMI), case-control status, and season of blood collection25,26.

Gene expression measurements

RNA was extracted from multiple cores of 1 or 1.5 mm taken from formalin fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tumor tissue (n=1–3 cores) and normal-adjacent (n=3–5 cores) tissues using the Qiagen AllPrep RNA isolation kit. Normal-adjacent tissues were obtained >1 cm away from the edge of the tumor. A detailed protocol has been published previously27–29 (microarray accession number: GSE115577). In brief, we profiled transcriptome-wide gene expression using Affymetrix Glue Grant Human Transcriptome Array 3.0 (hGlue 3.0) and Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 (HTA 2.0) microarray chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). We used robust multi-array averages to perform normalization (RMA; Affymetrix Power Tools (ATP)), log-2 transformed the data, and conducted sample quality control with Affymetrix Power Tools probeset summarization based metrics. A total of 1,577 samples (882 tumor tissues and 695 normal-adjacent tissues) from 954 invasive breast cancer cases passed quality control. Participant characteristics were similar among breast cancer cases with and without gene expression measurement30. For genes that were mapped by multiple probes, we selected the most variable probe to represent the gene. Our current analyses included 17,791 (70%) genes that were profiled in both platforms. Technical variabilities (batch) were controlled using ComBat—an empirical Bayes method used to control for known batch effects31. Genes with low expression (<25th percentile) were removed from the analyses.

Covariates

We obtained information on age, body mass index (BMI), fasting status and seasonality via questionnaires collected at the time of blood collection. Race, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), year of breast cancer diagnosis, characteristics (tumor stage, tumor grade) and treatment information (chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone therapy) were obtained via the biennial NHS and NHSII questionnaires. ER status was determined via central review of breast cancer tissue microarrays, and filled with pathological reports if missing. We computed B cell, CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, neutrophil, macrophage and dendritic cell proportions with Tumor IMmune Estimation Resource (TIMER), which uses constrained least squares fitting on informative genes to predict the abundance of immune cell infiltration in bulk tumor tissues32,33. Our gene expression analysis included women with complete information on 25(OH)D measurements, transcriptional profiling and covariates, resulting in 659 breast cancer cases (604 tumor tissues, 473 normal-adjacent tissues; 1077 total samples). Analysis for recurrence was restricted to subjects with tumor tissue microarrays.

Women who provided a blood sample were quite similar to the overall NHS cohort. For example, we observed (blood versus overall cohort): mean age (56 versus 56 yrs), BMI (25.5 versus 25.7 kg/m2), parity (3.0 versus 3.0), oral contraceptive use duration (51 versus 50 months), and current smokers (13 versus 17%). Since NHS cohorts consist of primarily white women, and race distributions was also similar comparing the nested case-control participants (96% white) versus the full cohort (97% white). For physical activity (metabolic equivalent tasks), mean is 19.02 (hr/wk) for the blood nested case-control and 20.16 (hr/wk) for full cohorts.

Breast cancer recurrence

Breast cancer recurrences are ascertained through supplemental questionnaires sent to living cohort members with a prior confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer. An internal validation study found 92% sensitivity and 92% specificity for the self-report of breast cancer recurrence compared with medical record review. Additionally, reported new cancers of the liver, bone, brain, and lung on biennial questionnaires, subsequent to a breast cancer diagnosis, are also assumed to be breast cancer recurrences, as these are common sites of metastasis. Finally, for cohort members who died from breast cancer without having previously reported a recurrence, a recurrence is assumed to have occurred. If the death from breast cancer occurred more than four years after the initial diagnosis, the date of recurrence is assigned to two years prior to the date of death (the median survival time for metastatic breast cancer). If the death from breast cancer occurred within four years of the initial diagnosis, the date of recurrence is assigned to be halfway between the dates of initial diagnosis and death. Approximately 40% of breast cancer recurrences in the cohorts are identified through self-report in questionnaires or new diagnosis at common sites of metastasis, while the remaining 60% are assumed to occur in women who died from breast cancer without reporting a recurrence. Recurrence-free survival is then defined as the time from diagnosis to breast cancer recurrence or end of follow-up (December 2015), censoring individuals who died from causes other than breast cancer at the time of death.

Statistical analysis

i. Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and breast cancer recurrence

Association of pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D with breast cancer recurrence was examined by using Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Recurrence-free survival (RFS) is defined as the time (in months) that elapsed between breast cancer diagnosis and breast cancer recurrence, diagnosis of cancer in common sites of recurrence (i.e., bone, brain, liver and lung), or death from breast cancer without reported recurrence30. Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D was modeled continuously and as a dichotomized variable at 30 ng/ml, as previous observational studies and Endocrine Society Guidelines suggest that a relatively high plasma level (≥30 ng/mL) is needed to achieve physiological benefits other than bone health34–36. We defined plasma 25(OH)D ≥30 ng/mL as “sufficient”, and <30 ng/ml as “insufficient”. In the multivariable Cox regression models, we controlled for age at blood collection (continuous), BMI at blood collection (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), race (white, non-white), tumor stage (continuous; I, II, III), tumor grade (continuous; low, intermediate, high), chemotherapy (ever use, never use, missing/unknown), radiotherapy (ever use, never use, missing/unknown), and hormone therapy (ever use, never use, missing/unknown). We assessed statistical interactions by ER status, and additionally stratified the analyses by ER status. The proportional hazards assumption was satisfied by evaluating a time-dependent variable, which was a product term between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and log survival time (p>0.05). Kaplan-Meier survival curve was constructed stratified by pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D (≥30 ng/mL or <30 ng/mL). As sensitivity analyses, we restricted study participants to women with early stage (I and II) breast cancer and excluded women with short lag time between diagnosis and recurrence (within 3 years). We additionally adjusting for season with categorical variables (spring, summer, fall, winter) or with Fourier series terms cos(2π * doy/365.25) and sin(2π * doy/365.25), where doy represents day of year37. Since our previous study from the same population showed no statistically significant interaction between menopausal status and 25(OH)D levels, we did not stratify the analysis by menopausal status.

ii. Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and breast tumor gene expression

For each individual gene, we evaluated the association between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D with transcriptome-wide gene expression using covariate-adjusted linear regression (limma)38. We adjusted in each regression model the following covariates selected a priori: age at blood collection (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), menopausal status and MHT use (post-menopausal not using, post-menopausal using, premenopausal or unknown), BMI at blood collection (continuous), fasting status at blood drawn (fasting, not fasting, not known), season (spring, summer, fall, winter) and surrogate variables generated from the transcriptome data (the leek method from Bioconductor sva package in R)39. We also explored an alternative method of adjusting for season with Fourier series terms as previously described37. All analyses were performed separately for tumor and normal-adjacent tissues, and we stratified the analysis by ER status of the tumor. We consider a gene to be significant transcriptome-wide if it met FDR p-value of pBH<0.0540.

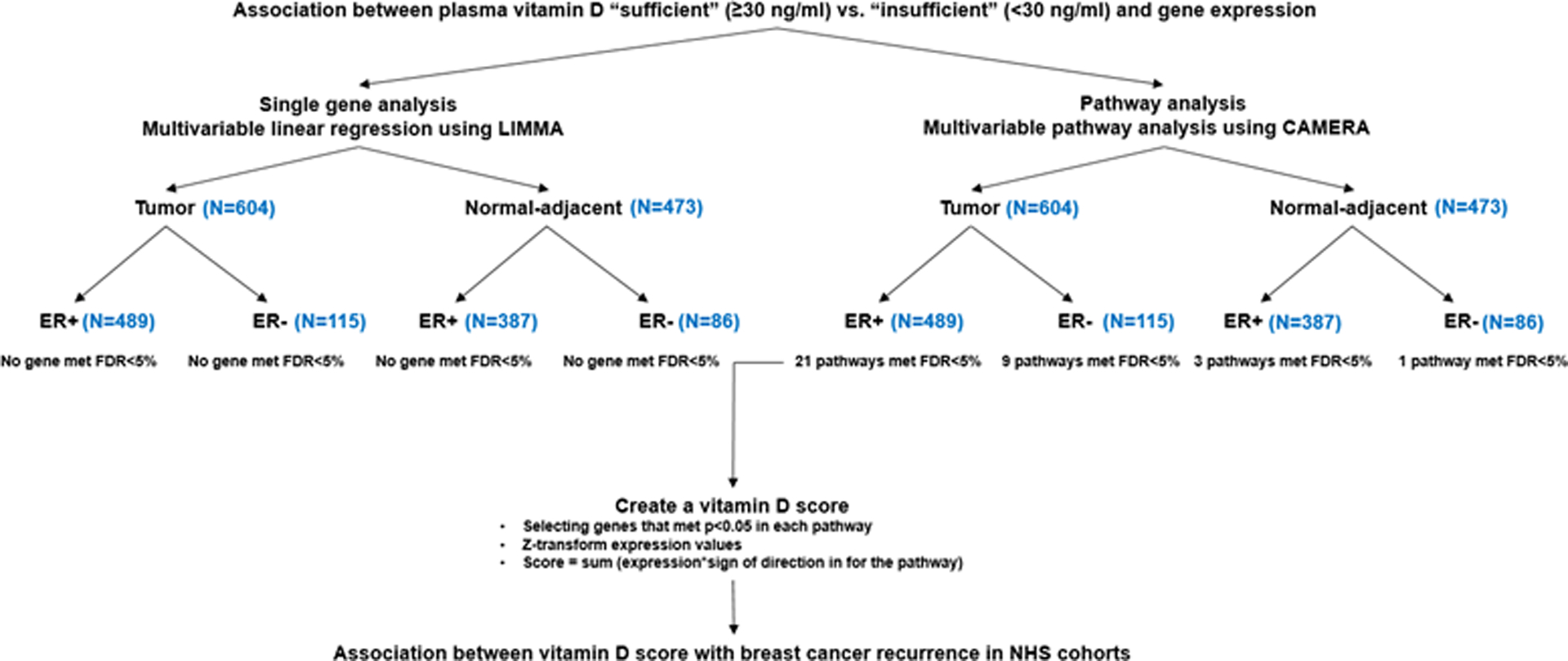

Using a competitive gene set testing procedure—Correlation Adjusted Mean Rank (CAMERA), we explored functional enrichment of biological pathways associated with pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D41. This method estimates the variance inflation factor associated with inter-gene correlation, and incorporated into rank-based test procedures. CAMERA correctly controls for type I error rate regardless of inter-gene correlations, and provides valid testing results based on gene permutation even when genes in the test sets are correlated41.We chose the 50 “hallmark” gene sets from the Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/). These “hallmark” gene sets were thought to reduce redundancy while provide effective summary of most of the relevant information of the original founder sets. In these analyses, we controlled for the same set of covariates as for the single-gene analysis, and chose an inter-gene correlation of 0.01. Figure 1 shows the flow of the analyses.

Figure 1.

Study flow for assessing 25(OH)D associated gene expression regulation for breast tumor progression using transcriptome-wide profiling.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 and in R 3.1.4.

iii. Tumor tissue derived gene expression score for pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and breast cancer recurrence

Among gene expression pathways that were significant after FDR correction in ER-positive tumor samples, we identified the individual genes that were nominally statistically significantly associated with 25(OH)D (p<0.05) and created a created the 25(OH)D gene expression score based on unique genes from the significantly enriched pathways. The 25(OH)D gene expression score was calculated as ∑(z-transformed genes from positively regulated pathways) - ∑(z-transformed genes from negatively regulated pathways). We present three sets of Cox models: model 1 adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous) and year of diagnosis (continuous); model 2 additionally adjusted for tumor stage (continuous; I, II, III) and tumor grade (continuous; low, intermediate, high); model 3 additionally adjusted for treatment modality, i.e., chemotherapy (ever use, never use, missing/unknown), radiotherapy (ever use, never use, missing/unknown), and hormone therapy (ever use, never use, missing/unknown). We tested the violation of the proportional hazards assumption by evaluating an interaction term between 25(OH)D score and log survival time (p>0.05). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis by further restricting to women with early stage (I and II) breast cancer.

iv. Generalizability of the derived 25(OH)D gene expression score: association between 25(OH)D gene expression score and disease free survival for ER-positive breast cancer in METABRIC

To assess if the 25(OH)D gene expression score derived in the NHS was generalizable to other populations, we leveraged an independent dataset, Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC). Using the same gene signature derived in NHS (described above) for ER-positive breast cancer, we calculated the 25(OH)D score using the available gene expression data in ER-positive tumor in METABRIC. It is important to note, METBRIC does not have circulating vitamin D and the calculation of the score is based on that from NHS. We then examined if this score was associated with recurrence free survival. We included 737 stage I to III ER-positive breast cancer cases with complete information on transcriptional profiling, breast cancer specific survival data and covariate information. Transcriptional profiling was performed on the Illumina HT-12 v3 platform42,43. All clinical and gene expression data is deposited at the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/) under accession number EGAS0000000008342,43. We present 3 sets of Cox regression models, adjusting for the same covariates as described in the previous section. We restricted 25(OH)D score to the same range as for the NHS studies, and further restricted the analyses to women with early stage (I and II) breast cancer.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Among 604 women who contributed to tumor data, 215 participants had “sufficient” levels of pre-diagnostic circulating concentration of 25(OH)D (≥30 ng/ml) while 389 had “insufficient” levels (<30 ng/ml). Mean age at blood drawn was slightly younger in women with sufficient levels of 25(OH)D compared to insufficient levels (mean (SD)=53.4 (8.6) vs. 54.8 (8.2) years) (Table 1). In the sufficient 25(OH)D group, 17% of participants were postmenopausal and had never used MHT, 33% of women were postmenopausal and used MHT, while 50% were either premenopausal or did not report MHT use. A higher proportion of women in the insufficient 25(OH)D group were postmenopausal and had not used MHT. Average BMI was 24.5 kg/m2 (SD=4.1) in the sufficient 25(OH)D group and was 25.9 kg/m2 (SD=4.9) in the insufficient group. Participants in this study were predominantly white (96%). Dietary vitamin D was higher in the sufficient 25(OH)D group compared to the insufficient group (mean (SD)=518.6 IU/day (285.5) vs. 445.6 (267.2)). We observed Gaussian distribution of 25(OH)D levels for the study population (Supplementary Figure 1). Median time between blood draw and cancer diagnosis was 6.4 years (IQR=7.2 years), while median time between blood draw and tumor microarray assessment was 23 years (IQR=6.1 years)

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of breast cancer cases in the Nurse’ Health Studies (NHS) who contributed to tissue expression data (N=604).

| Circulating 25(OH)D concentration | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Sufficient (≥30 ng/ml) | Insufficient (<30 ng/ml) |

| N=215 | N=389 | |

| Age at blood draw (year) [mean (SD)] | 53.4 (8.6) | 54.8 (8.2) |

| Year of breast cancer diagnosis [median (IQR)] | 1999 (9.5) | 2000 (8.0) |

| Menopausal status / menopausal hormone therapy use at blood draw [n (%)] | ||

| Post-menopausal not using | 37 (17%) | 97 (25%) |

| Post-menopausal using | 70 (33%) | 117 (30%) |

| Premenopausal/unknown | 108 (50%) | 175 (45%) |

| BMI at blood draw (kg/m2) [mean (SD)] | 24.5 (4.1) | 25.9 (4.9) |

| Fasting status at blood draw [n (%)] | ||

| Yes | 99 (46%) | 192 (49%) |

| No | 50 (23%) | 95 (24%) |

| Unknown | 66 (31%) | 102 (27%) |

| Race [n (%)] | ||

| White | 206 (96%) | 374 (96%) |

| Non-white | 9 (4%) | 15 (4%) |

| Season of blood draw [n (%)] | ||

| Spring | 47 (22%) | 115 (30%) |

| Summer | 63 (29%) | 106 (27%) |

| Fall | 61 (28%) | 79 (20%) |

| Winter | 44 (21%) | 89 (23%) |

| MET hr-wka [mean (SD)] | 21.2 (22.0) | 17.8 (21.5) |

| Total vitamin D intakeb (IU/day) [mean (SD)] | 518.6 (285.5) | 445.6 (267.2) |

MET (metabolic equivalent task) assessed one cycle before blood collection

Total vitamin D intake from food frequency questionnaire assessed one cycle before blood collection

Association between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D with breast cancer recurrence

Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D was not associated with overall (ER-positive and ER-negative) breast cancer recurrence (median follow-up=13.0 years), however, a statistically significant interaction (p=0.005) was observed between 25(OH)D and ER status (Table 2). We next stratified the analysis by ER status, and observed that higher pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D was associated with lower risk of recurrence among ER-positive cases, but not ER-negative breast cancer cases. Every 5 ng/ml increase in 25(OH)D level was associated with a 13% decrease in risk of recurrence in women with ER positive cancers (HR=0.87; 95% CI=0.76 to 0.99). We also observed a similar reduction in risk in ER positive diseases when we examined 25(OH)D as dichotomized variable, although it was not significant (≥30 ng/ml vs. <30 ng/ml, HR=0.72; 95% CI=0.42 to 1.22; Table 2; Supplementary Figure 2). An analysis restricting women to early stage (I and II) breast cancer yielded similar results (Table 2). After excluding women with short lag time between diagnosis and recurrence (≤3 years), we also observe comparable association between 25(OH)D (dichotomized) and recurrence (HR=0.72; 95% CI: 0.52; 0.99, p-value=0.05). Adjusting for season using categorical variables or using Fourier series terms also gave comparable results, every 5 ng/ml increase in 25(OH) levels was associated with a 14% decrease in risk of recurrence for ER-positive disease (HR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.76; 0.99). Among ER-negative cases, null associations were observed when we modeled 25(OH)D continuously (HR=1.07; 95% CI: 0.91 to 1.27; Table 2) or as a categorical variable (HR=1.34; 95% CI=0.54 to 3.29; Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D level and breast cancer recurrence among women with invasive breast cancer who contributed to tissue expression data.

| Stage I to III | Overall | ER-positive | ER-negative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrences/Cases | 94/592 | 68/480 | 26/112 | ||||

| Continuous | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | pinteraction |

| Every 5 ng/ml increase | 0.97 (0.88; 1.08) | 0.594 | 0.87 (0.76; 0.99) | 0.04 | 1.07 (0.91; 1.27) | 0.409 | 0.005 |

| Categorical | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | pinteraction |

| <30 ng/ml | 1.0 (ref) | -- | 1.0 (ref) | -- | 1.0 (ref) | -- | -- |

| ≥30 ng/ml | 0.97 (0.63; 1.50) | 0.894 | 0.72 (0.42; 1.22) | 0.221 | 1.34 (0.54; 3.29) | 0.528 | 0.05 |

| Stage I and II | Overall | ER-positive | ER-negative | ||||

| Recurrences/Cases | 72/544 | 50/440 | 22/104 | ||||

| Continuous | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | pinteraction |

| Every 5 ng/ml increase | 0.96 (0.86; 1.08) | 0.489 | 0.85 (0.73; 0.99) | 0.03 | 1.09 (0.92; 1.30) | 0.328 | 0.006 |

| Categorical | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | pinteraction |

| <30 ng/ml | 1.0 (ref) | -- | 1.0 (ref) | -- | 1.0 (ref) | -- | -- |

| ≥30 ng/ml | 0.98 (0.60; 1.62) | 0.951 | 0.64 (0.35; 1.19) | 0.162 | 1.81 (0.70; 4.71) | 0.222 | 0.02 |

Model adjusted for age at blood collection (continuous), BMI at blood collection (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), race (white, non-white), tumor stage (continuous), tumor grade (continuous), chemotherapy (yes, no, missing/unknown), radiotherapy (yes, no, missing/unknown), and hormone therapy (yes, no, missing/unknown).

Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and gene expression analysis

Overall, we did not observe a statistically significant association between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and any single gene in tumor or normal-adjacent tissues stratified by ER status (FDR<5%). We present in Supplementary Figure 3 differentially expressed genes with relatively large effect size (i.e., genes with log fold change larger than the average of the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile) and had a nominal p value less than 0.001 in tumor and normal-adjacent ER-positive samples.

Competitive gene set enrichment analysis identified 21 pathways significantly enriched in ER-positive tumor tissues, and 3 significantly enriched in ER-positive normal-adjacent tissues (FDR<5%) (Table 3a). Those pathways included genes implicated in proliferation and mitogenesis, cellular stress, immune response, and cancer cell metabolism. While all those pathways were down-regulated in ER-positive tumor tissues except for KRAS signaling, gene sets involved in cellular stress and proliferation were up regulated in normal-adjacent ER-positive tissues. In ER-negative tumor and normal-adjacent tissues, we found 9 pathways that were differentially enriched (FDR<5%) in relation to high 25(OH)D (Table 3b). The biological processes included proliferation, cellular stress, tumor microenvironment, and immune response. However, we observed heterogeneous molecular response between ER-positive and ER-negative tumors—overlapping pathways (n=5) identified in ER-positive and ER-negative tumors tended to have opposite directions of association.

Table 3a.

Pathway enrichment analysis of pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D level in ER-positive breast tumor and normal-adjacent tissues. Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D level was modeled as a categorical variable of “sufficient” (≥30 ng/ml) vs. “insufficient” (<30 ng/ml).

| Tumor ER-positive (N=489) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation and mitogenic effects | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 | 191 | Down | 2.65E-10 |

| HALLMARK_MTORC1_SIGNALING | 166 | Down | 5.75E-06 |

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT | 149 | Down | 1.52E-04 |

| HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY | 184 | Down | 3.52E-04 |

| HALLMARK_PI3K_AKT_MTOR_SIGNALING | 92 | Down | 3.84E-04 |

| HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS | 151 | Down | 2.62E-03 |

| HALLMARK_ANDROGEN_RESPONSE | 88 | Down | 6.29E-03 |

| HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_LATE | 178 | Down | 7.14E-03 |

| HALLMARK_KRAS_SIGNALING_DN | 139 | Up | 1.70E-02 |

| HALLMARK_TGF_BETA_SIGNALING | 53 | Down | 2.65E-02 |

| Cellular stress | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_PROTEIN_SECRETION | 85 | Down | 4.03E-08 |

| HALLMARK_UNFOLDED_PROTEIN_RESPONSE | 105 | Down | 5.34E-06 |

| HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION | 184 | Down | 3.58E-04 |

| HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS | 144 | Down | 7.88E-03 |

| HALLMARK_HYPOXIA | 176 | Down | 2.99E-02 |

| HALLMARK_REACTIVE_OXIGEN_SPECIES_PATHWAY | 42 | Down | 2.99E-02 |

| Immunosuppression | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB | 168 | Down | 1.27E-02 |

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE | 75 | Down | 2.36E-02 |

| Cancer cell metabolism | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_GLYCOLYSIS | 168 | Down | 9.88E-04 |

| Invasion and metastasis | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 174 | Down | 1.52E-04 |

| HALLMARK_ANGIOGENESIS | 30 | Down | 2.99E-02 |

| Normal-adjacent ER-positive (N=387) | |||

| Cellular stress | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION | 184 | Up | 1.18E-02 |

| Immune response | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION | 151 | Down | 2.44E-02 |

| Proliferation and mitogenic effects | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_ADIPOGENESIS | 186 | Up | 2.44E-02 |

In each regression model, we adjusted for the following covariates selected a priori: age at blood draw (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), menopausal hormone replacement therapy at blood draw (post-menopausal not using / post-menopausal using / premenopausal or unknown), body mass index (BMI) at blood draw (continuous), fasting status at blood draw (fasting / not fasting / not known), season (spring / summer / fall / winter), and surrogate variables generated from the transcriptome data.

Table 3b.

Pathway enrichment analysis of pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D level in ER-negative breast tumor and normal-adjacent tissues. Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D level was modeled as a categorical variable of “sufficient” (≥30 ng/ml) vs. “insufficient” (<30 ng/ml).

| Tumor ER-negative (N=115) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation and mitogenic effects | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1** | 191 | Up | 1.56E-06 |

| HALLMARK_MTORC1_SIGNALING** | 166 | Up | 5.38E-04 |

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT** | 149 | Up | 7.55E-04 |

| HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS* | 151 | Up | 1.58E-03 |

| HALLMARK_CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS** | 63 | Up | 1.80E-04 |

| Cellular stress | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_UNFOLDED_PROTEIN_RESPONSE** | 105 | Up | 2.29E-02 |

| HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION* | 184 | Up | 7.63E-03 |

| Tumor microenvironment | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_MYOGENESIS | 179 | Down | 2.29E-02 |

| Normal-adjacent ER-negative (N=86) | |||

| Immune response | N | Direction | FDR |

| HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB | 168 | Up | 2.31E-03 |

In each regression model, we adjusted for the following covariates selected a priori: age at blood draw (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), hormone replacement therapy at blood draw (post-menopausal not using / post-menopausal using / premenopausal or unknown), body mass index (BMI) at blood draw (continuous), fasting status at blood draw (fasting / not fasting / not known), season (spring / summer / fall / winter), and surrogate variables generated from the transcriptome data.

We highlighted pathways that showed statistically significant interaction between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D level and ER status.

p<0.05;

p<0.1

We considered alternative cut-points for defining ER-positivity. When we defined ER-positivity as ≥10% of cells staining positive, the association tended to become stronger between 25(OH)D and molecular pathways (measured by the magnitude of FDR-corrected p-values), suggesting a potential cross-talk between 25(OH)D and ER (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, we observed more CD8+ T cell infiltration in ER-negative tumor as compared to ER-positive tumor (Supplementary Figure 2). As a sensitivity analysis, we introduced an interaction term (i.e., time between blood draw and cancer diagnosis and 25(OH)D), and found that pathway analysis results would unlikely to be affected by duration between blood draw and diagnosis (p for interaction ranges from 0.15 to 0.98). Adjusting for season using Fourier series term and as categorical variables yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 2)

Circulating 25(OH)D derived gene expression signatures and breast cancer recurrence

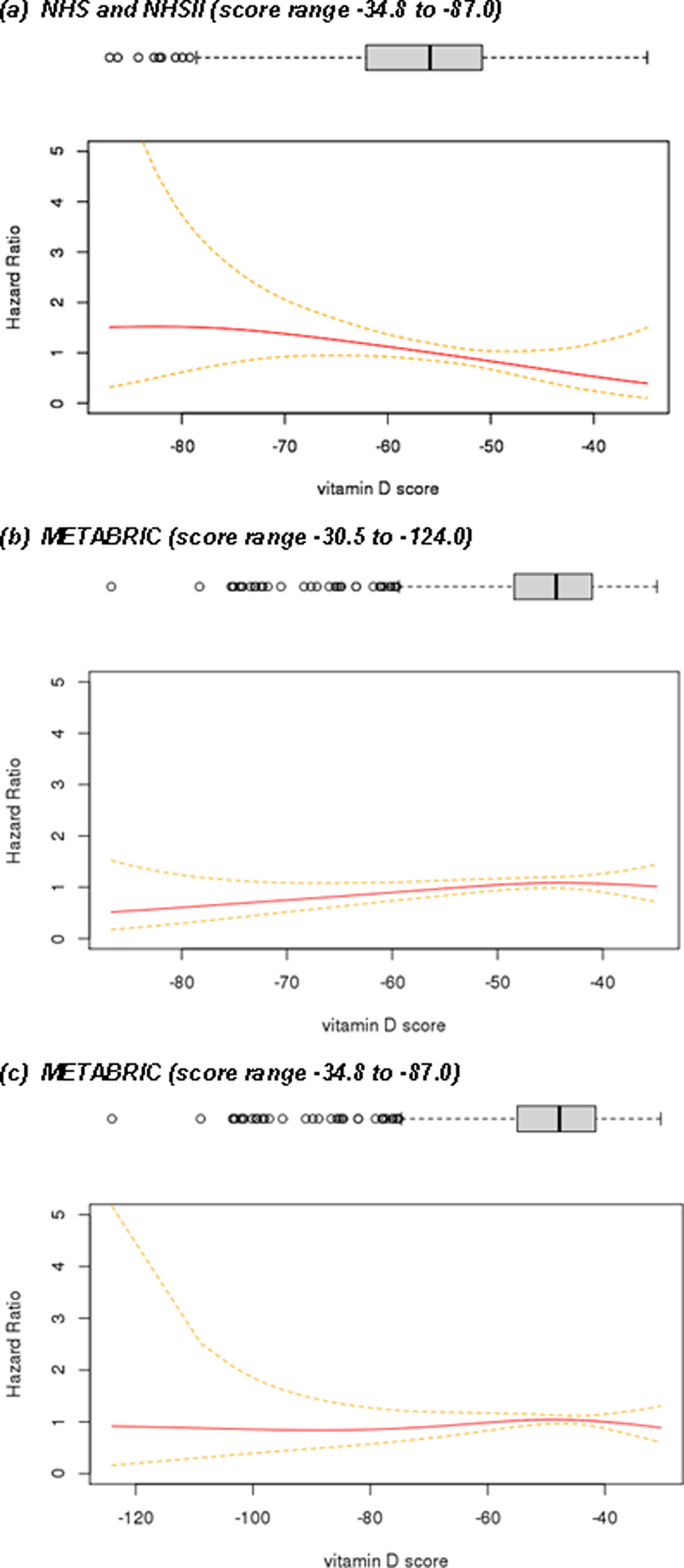

Among women with stage I to III ER-positive breast cancer, a 10-unit increase in 25(OH)D gene expression score was marginally associated with a 18% reduction in risk of recurrence (HR=0.77; 95% CI=0.59 to 1.01, p-value=0.058) in the NHS cohorts (Table 4, model 3; Figure 2). We observed similar magnitude of effect estimates when we restricted the analysis to participants with early stage (I and II) breast cancer. However, when we examined the generalizability of these findings in another dataset, we did not find that this score was associated with breast cancer recurrence among ER-positive cancer cases in METABRIC (Figure 3; Supplementary Table 3 and 4). In the fully adjusted model in METABRIC, HR was 1.02 for every 10 unit increase in 25(OH)D gene expression score (95% CI: 0.92; 1.15, p-value=0.617) for stage I to III breast cancer cases (Supplementary Table 4). Findings remain similar when we restricted 25(OH)D gene expression scores to the same range as for NHS (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Association between 25(OHD) gene expression score and breast cancer recurrence among ER positive breast cancer cases in NHS and NHSII.

| Stage I to III | ||

|---|---|---|

| Recurrence/Patient | 68/480 | |

| Score range | (−34.8 to −87.0) | |

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Model 1 | 0.82 (0.63; 1.07) | 0.145 |

| Model 2 | 0.78 (0.60; 1.02) | 0.066 |

| Model 3 | 0.77 (0.59; 1.01) | 0.058 |

| Stage I and II | ||

| Recurrence/Patient | 50/440 | |

| Score range | (−34.8 to −87.0) | |

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Model 1 | 0.77 (0.56; 1.05) | 0.097 |

| Model 2 | 0.76 (0.55; 1.04) | 0.087 |

| Model 3 | 0.76 (0.55; 1.05) | 0.097 |

In model 1, we adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous) and year of diagnosis (continuous); model 2 adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), tumor stage (continuous) and tumor grade (continuous); model 3 adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), tumor stage (continuous), tumor grade (continuous), treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy or hormone therapy).

Figure 2.

Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D score derived from pathway analysis and breast cancer recurrence among women with stage I to III ER-positive breast cancer.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective population-based study, higher pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D (measured 6.4 years before diagnosis at one time point) was inversely associated with breast cancer recurrence among women with ER-positive in the NHS and NHSII, but not ER-negative breast cancer. After multiple testing corrections, no single gene was significantly associated with 25(OH)D in either breast tumor or adjacent tissues for ER-positive and ER-negative diseases. However, pathway analysis identified multiple gene sets that were significantly enriched and down-regulated at a transcriptome-wide threshold in ER-positive breast tumor, which included genes associated with proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion, inflammation and cancer cell metabolism. Further, among ER-positive breast cancers, we observed a marginally significant inverse association between the composite score summarizing the gene expression of 25(OH)D signatures in tumor tissue and breast cancer recurrence in the NHS cohorts. However, the 25(OH)D score derived based on NHS data did not translate to a publicly available dataset of METABRIC, suggesting that further refinement is needed to improve generalizability.

An increasing body of evidence supports an inverse association between vitamin D and cancer mortality11–19. Large-scale meta-analyses of 17,332 cancer patients showed that higher circulating 25(OH)D—measured at or near the time of cancer diagnosis—was associated with improved survival among lymphoma, colorectal and breast cancer patients15. Among 4,413 breast cancer cases in a separate meta-analysis, the pooled hazard ratios comparing highest with lowest quintiles were 0.65 (95% CI: 0.49; 0.86) for total mortality and 0.58 (95% CI: 0.38; 0.84) for breast cancer specific mortality14. A recent case-control study also revealed that serum circulating 25(OH)D, measured at the time of diagnosis, was associated with lower risk of breast cancer specific mortality17. Compared with the lowest tertile, women in the highest tertile of 25(OH)D levels had a 28% decrease in total mortality (HR=0.72, 95% CI=0.54 to 0.98)17. A meta-analysis of current RCTs using high doses of vitamin D supplementation showed significant improvement in breast cancer survival with significantly reduced total cancer mortality, but did not demonstrate a reduction in total cancer incidence25. The large vitamin D and omega-3 trial (VITAL)—which assessed the effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation (2,000 IU/day) and omega 3 (1 g/day) on cancer incidence and mortality—showed no association between pre-diagnostic vitamin D supplementation and total death or breast cancer specific death20. However, a protective effect of vitamin D was observed for overall cancer mortality after excluding cases that occurred in the first 2-years of follow-up20. Since our median follow-up time was 12.8 years, a longer follow-up for VITAL maybe needed to observe potential beneficial effects of vitamin D on breast cancer survival.

Consistent with previous findings in the NHS cohorts showing that post-diagnostic vitamin D supplement use was associated with improved breast cancer survival in ER-positive diseases21, we observed that higher pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D was inversely associated with breast cancer recurrence only among ER-positive breast cancer cases. A heterogeneous molecular response was also observed between ER-positive and ER-negative breast tumors. In addition to the relatively small sample size of the ER-negative sub-group, we postulate several biological reasons for the observed discrepancy with the ER-positive sub-group. Previous experimental studies have shown that 1α,25(OH)2D suppress aromatase and COX-2 expression in both cancerous epithelial cells and stromal adipose fibroblasts in the breast44. Aromatase and COX-2 are key enzymes in the estrogen signaling pathway, and help convert androgenic precursors and arachidonic acid to potent proliferative compounds of estrogen and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). These findings support a potential cross-talk between 1α,25(OH)2D and inhibition of estrogen signaling in promoting cellular proliferation. Supported by our data, the strength of the association between 25(OH)D and proliferation-related gene expression pathways became more profound (measured by FDR) when we changed the definition of ER-positivity from ≥1% of tumor nuclei stained positive to ≥10% of tumor nuclei stained positive. It is well-documented that ER-negative tumor is more heterogeneous than ER-positive tumor45. In our study, RNA was extracted from 1 or 1.5 mm cores from bulk tumor tissues. Therefore, it is difficult to rule out the possibility that a more heterogeneous tumor subtype gives rise to less robust biological signals. Using TIMER, a mathematical algorithm to deconvolute tumor cellular heterogeneity, we found more infiltrated CD8+ T cells in ER-negative tumors as compared to ER-positive tumors.

Given that higher pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D was associated with better survival among ER-positive breast cancers in our data, we derived a gene expression score for 25(OH)D using differential enriched pathways and found that down-regulation of the 25(OH)D gene expression signature was associated with lower risk of breast cancer recurrence in the NHS cohorts. Several in vitro experiments also studied the impact of 1α,25(OH)2D on differential gene expression at a transcriptome-wide level46,47. Consistent with our findings, in cell lines derived from normal mammary tissue and breast cancer cells, gene set enrichment analysis highlighted several pathways (including cell cycle and proliferation, immunomodulation, cell metabolism, apoptosis and cell death, as well as cellular adhesion, migration and invasion) being altered by 1α,25(OH)2D46,47. Nevertheless, our 25(OH)D score may not be generalizable to other datasets, as we observed null association between 25(OH)D score with breast cancer recurrence in METABRIC. This lack of consistent findings between datasets may reflect both real biologic differences in tumors (e.g., stage, grade) and study populations and/or methodologic differences. The METABRIC dataset consists of samples that were assayed in multiple labs and batches, while the NHS/NHS2 were conducted in two batches using similar array technology. Additional research in other study populations is warranted to determine whether our findings can be confirmed in other studies.

We hypothesize that pre-diagnostic factors not only influence risk, but also recurrence. This is especially evident for vitamin D, since experimental studies suggest that vitamin D inhibits tumor growth and proliferation44,48–51, but data are limited on the effect of vitamin D on tumor initiation. A previous randomized trial of high dose vitamin D (VITAL) also showed that vitamin D randomization was associated with reduced overall cancer mortality after excluding cases that occurred in the first 2-years of follow-up (but not risk)20. Pre-diagnostic factors may be a reflection of a person’s general health status and well-being (immunity, damage and repair mechanisms and etc.), which are all important determinants for one’s ability to recover or survive post-diagnosis.

Our study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study linking pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D, differential gene expression in breast tumor and breast cancer recurrence in human population based studies. Our study included a relatively large sample of ER-positive cases, which enabled us to robustly identify differential survival data and gene expression patterns in relation to circulating 25(OH)D levels. Vitamin D supplementation represents a personal level secondary cancer prevention nutritional factor, which could be easily implemented and integrated into daily life to reduce breast cancer disease burden and added to treatment protocols to improve treatment results. There are also limitations to our study. Our FFPE tissue blocks were archived for 9–30 years, and differential RNA degradation may be of concern. To minimize variations arising from different sample storage conditions and the age of FFPE tissue, we adjusted for year of diagnosis in all regression models. Our pilot work also showed high correlations between ESR1, PGR, and ERBB2 expression with ER, PR, and HER2 immunohistochemistry staining27,28. Our microarray analysis was based on RNA extracted from bulk tumor and adjacent tissues. Since ER-negative tumor is often more heterogeneous than ER-positive tumor, 25(OH)D associated biological signals may be masked in a more heterogeneous tissue subtype. Future research with larger sample size is warranted to study the effect of vitamin D on disease progression in ER-negative breast tumors. Finally, our study had only a single measurement of each subject’s pre-diagnostic levels of 25(OH)D. It would have been better to have follow-up assays but previous work in this population of subjects noted the feasibility of using a single measurement of multiple biomarkers including 25(OH)D that can reliably estimate average levels over a 1- to 3-year period in epidemiologic studies52. Further, in a previous study that had pre-diagnostic plasma 25(OH)D measured approximately 10 years apart (1989–1990 to 2000–2002) from the same subset of controls (n=238) with blood collected in concordant seasons, intraclass correlation (ICCs) were 0.51, 95% CI(0.42–0.60)53. Potential survivorship bias may occur for analyses with recurrence as an outcome since not all breast cancer cases reported their recurrence status. For those cancer cases who did not return supplementary questionnaires, did not die and did not report subsequent new cancers at the liver, bone, brain and lung, we assumed that they did not have recurrence. Nonetheless, such misclassification is likely to be non-differential since missingness to report a recurrence would not be related to the exposure variable (pre-diagnostic 25(OH)D) and would bias the results towards the null. Our study did not have information on post-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D. Vitamin D supplementations maybe prescribed to women after cancer treatment due to concerns about bone density, therefore, among breast cancer cases, pre-diagnostic 25(OH)D level may not truly reflect long-term circulating 25(OH)D concentrations, especially during and immediately after cancer treatment. However, given its temporality, post-diagnostic 25(OH)D would not confound our associations. Future studies is warranted to include post-diagnostic 25(OH)D measurements to further verify our conclusions.

Our findings suggest that higher pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D was associated with decreased risk of recurrence among patients with ER-positive breast cancer in the NHS, potentially through down regulating signaling pathways in tumor that are primarily involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion, inflammation and cancer cell metabolism. Our results lend further support to the use of vitamin D as a potential secondary prevention strategy for reducing cancer progression in ER-positive breast cancer. However, the 25(OH)D score generated based on NHS did not translate to publicly available data, suggesting that further refinement is need to improve the generalizability of the score. Future studies which include post-diagnostic 25(OH)D measures would also be important to verify our findings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute [UM1 CA186107 (to A. Heather Eliassen), UM1 CA176726 (to A. Heather Eliassen), P01 CA87969 (to A. Heather Eliassen and Rulla M. Tamimi), U19 CA148065 (to Rulla M. Tamimi, Peter Kraft), R01 CA178263 (to Rulla M. Tamimi and Kathryn M. Rexrode) and R01 CA166666 (to Susan E. Hankinson)], National Institute of Health Epidemiology Education Training Great to NCD [NIH T32 CA09001] (to A. Heather Eliassen), the Susan G. Komen for the Cure ® [IIR13264020, SAC110014] (to Rulla M. Tamimi and Susan E. Hankinson), and the Prevent Cancer Foundation (to Cheng Peng). The authors thank all participants and coordinators of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Nurses’ Health Study II for their valuable contribution, and the cancer registries in the following states for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA and WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deeb KK, Trump DL & Johnson CS Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer 7, 684–700 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E & Feldman BJ The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer 14, 342–57 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh J Vitamin D and breast cancer: Past and present. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 177, 15–20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman D, P J, Bouillon R, Giovannucci E, Goltzman D and Hewison M Vitamin D, (Academic Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooi LL et al. Vitamin D deficiency promotes growth of MCF-7 human breast cancer in a rodent model of osteosclerotic bone metastasis. Bone 47, 795–803 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ooi LL et al. Vitamin D deficiency promotes human breast cancer growth in a murine model of bone metastasis. Cancer Res 70, 1835–44 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams JD et al. Tumor Autonomous Effects of Vitamin D Deficiency Promote Breast Cancer Metastasis. Endocrinology 157, 1341–7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Light BW et al. Potentiation of cisplatin antitumor activity using a vitamin D analogue in a murine squamous cell carcinoma model system. Cancer Res 57, 3759–64 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershberger PA et al. Calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) enhances paclitaxel antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo and accelerates paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 7, 1043–51 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q, Yang W, Uytingco MS, Christakos S & Wieder R 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and all-trans-retinoic acid sensitize breast cancer cells to chemotherapy-induced cell death. Cancer Res 60, 2040–8 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schottker B et al. Vitamin D and mortality: meta-analysis of individual participant data from a large consortium of cohort studies from Europe and the United States. BMJ 348, g3656 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin L et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D serum concentration and total cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 57, 753–64 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhury R et al. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomised intervention studies. BMJ 348, g1903 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maalmi H, Ordonez-Mena JM, Schottker B & Brenner H Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and survival in colorectal and breast cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Cancer 50, 1510–21 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li M et al. Review: the impacts of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on cancer patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99, 2327–36 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Koo J & Hood N Prognostic effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27, 3757–63 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao S et al. Association of Serum Level of Vitamin D at Diagnosis With Breast Cancer Survival: A Case-Cohort Analysis in the Pathways Study. JAMA Oncol 3, 351–357 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keum N & Giovannucci E Vitamin D supplements and cancer incidence and mortality: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 111, 976–80 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keum N, Lee DH, Greenwood DC, Manson JE & Giovannucci E Vitamin D Supplements and Total Cancer Incidence and Mortality: a Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Oncol (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manson JE et al. Vitamin D Supplements and Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med 380, 33–44 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole EM et al. Postdiagnosis supplement use and breast cancer prognosis in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139, 529–37 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poole EM et al. Body size in early life and adult levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3. Am J Epidemiol 174, 642–51 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertone-Johnson ER et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14, 1991–7 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eliassen AH et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of breast cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Breast Cancer Res 13, R50 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertrand KA et al. Premenopausal plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D, mammographic density, and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 149, 479–87 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosner B, Cook N, Portman R, Daniels S & Falkner B Determination of blood pressure percentiles in normal-weight children: some methodological issues. Am J Epidemiol 167, 653–66 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J et al. Alcohol consumption and breast tumor gene expression. Breast Cancer Res 19, 108 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heng YJ et al. Molecular mechanisms linking high body mass index to breast cancer etiology in post-menopausal breast tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kensler KH et al. PAM50 Molecular Intrinsic Subtypes in the Nurses’ Health Study Cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kensler KH et al. PAM50 Molecular Intrinsic Subtypes in the Nurses’ Health Study Cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 28, 798–806 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson WE, Li C & Rabinovic A Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 8, 118–27 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li T et al. TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Cancer Res 77, e108–e110 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li B et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol 17, 174 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tavera-Mendoza LE et al. Vitamin D receptor regulates autophagy in the normal mammary gland and in luminal breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E2186–E2194 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garland CF et al. Vitamin D and prevention of breast cancer: pooled analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 103, 708–11 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holick MF et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96, 1911–30 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gail MH et al. Calibration and seasonal adjustment for matched case-control studies of vitamin D and cancer. Stat Med 35, 2133–48 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smyth GK Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3, Article3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leek JT & Storey JD Capturing heterogeneity in gene expression studies by surrogate variable analysis. PLoS Genet 3, 1724–35 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benjamini Y, H Y Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the royal statistical society. Series B 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu D & Smyth GK Camera: a competitive gene set test accounting for inter-gene correlation. Nucleic Acids Res 40, e133 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtis C et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 486, 346–52 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prat A et al. Molecular features and survival outcomes of the intrinsic subtypes within HER2-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 106(2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnan AV, Swami S & Feldman D The potential therapeutic benefits of vitamin D in the treatment of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Steroids 77, 1107–12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Razzak AR, Lin NU & Winer EP Heterogeneity of breast cancer and implications of adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer 15, 31–4 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simmons KM, Beaudin SG, Narvaez CJ & Welsh J Gene Signatures of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Exposure in Normal and Transformed Mammary Cells. J Cell Biochem 116, 1693–711 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheng L et al. Identification of vitamin D3 target genes in human breast cancer tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 164, 90–97 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salehi-Tabar R et al. Vitamin D receptor as a master regulator of the c-MYC/MXD1 network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 18827–32 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elstner E et al. 20-epi-vitamin D3 analogues: a novel class of potent inhibitors of proliferation and inducers of differentiation of human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 55, 2822–30 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell MJ, Reddy GS & Koeffler HP Vitamin D3 analogs and their 24-oxo metabolites equally inhibit clonal proliferation of a variety of cancer cells but have differing molecular effects. J Cell Biochem 66, 413–25 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishnan AV, Swami S & Feldman D Vitamin D and breast cancer: inhibition of estrogen synthesis and signaling. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 121, 343–8 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotsopoulos J et al. Reproducibility of plasma and urine biomarkers among premenopausal and postmenopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19, 938–46 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eliassen AH et al. Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Risk of Breast Cancer in Women Followed over 20 Years. Cancer Res 76, 5423–30 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.