Abstract

The abundance and distribution of water within Mars through time plays a fundamental role in constraining its geological evolution and habitability. The isotopic composition of martian hydrogen provides insights into the interplay between different water reservoirs on Mars. However, D/H (deuterium/hydrogen) ratios of martian rocks and of the martian atmosphere span a wide range of values. This has complicated identification of distinct water reservoirs in and on Mars within the confines of existing models that assume an isotopically homogenous mantle. Here we present D/H data collected by secondary ion mass spectrometry for two martian meteorites. These data indicate that the martian crust has been characterized by a constant D/H ratio over the last 3.9 billion years. The crust represents a reservoir with a D/H ratio that is intermediate between at least two isotopically distinct primordial water reservoirs within the martian mantle, sampled by partial melts from geochemically depleted and enriched mantle sources. From mixing calculations, we find that a subset of depleted martian basalts are consistent with isotopically light hydrogen (low D/H) in their mantle source, whereas enriched shergottites sampled a mantle source containing heavy hydrogen (high D/H). We propose that the martian mantle is chemically heterogeneous with multiple water reservoirs, indicating poor mixing within the mantle after accretion, differentiation, and its subsequent thermochemical evolution.

Mars is comprised of a core, mantle, crust, and atmosphere, and this basic structure is the sum effect of its accretion, differentiation, and subsequent thermochemical evolution. The initial abundance, distribution, and isotopic composition of water within these structural components is poorly constrained, but important insights have been gained from analysis of martian meteorites, telescopic observations, and launched missions to Mars, including Mars-orbiting spacecraft, landers, and rovers1. Data from all of these efforts indicate that there are at least two isotopically distinct water reservoirs on Mars. One reservoir is thought to reside in the atmosphere and within surficial polar ice deposits that is characterized by a D/H ratio that is elevated relative to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (1.56×10−4) by a factor of 5 to 72–4, which is attributed to hydrogen loss over time from the upper atmosphere of Mars in the absence of a persistent and long-lived global magnetic field5. The second is thought to represent the primordial martian mantle with a D/H ratio of 1.99 ± 0.02 × 10−4, which is enriched relative to VSMOW by a factor of 1.36. Analyses of hydrous phases in martian meteorites and in-situ analyses of materials on the martian surface yield a wide range of D/H values that largely sit between these two endmembers7,8, so many previous studies have implicated mixing of these reservoirs and/or terrestrial contamination to explain the observed variations in D/H ratios. However, Mars lacks unambiguous evidence of once having Earth-style plate tectonics, and in the absence of plate tectonics, the crust acts as a physicochemical barrier between the atmosphere and mantle, hence it is a critical part of constraining any mixing model between the atmosphere and mantle reservoirs. Moreover, the H-isotopic composition of the martian crust remains poorly characterized, despite it being a major water reservoir on Mars9, which has impeded any systematic evaluation of proposed mixing models between the atmosphere and mantle. Here we have characterized the H-isotopic composition of the martian crust over the timespan of 3.9 to 1.5 billion years before the present using samples that are known to have interacted with martian crustal fluids, including Allan Hills (ALH) 84001 and Northwest Africa (NWA) 7034.

Isotopic signature of water in the martian crust

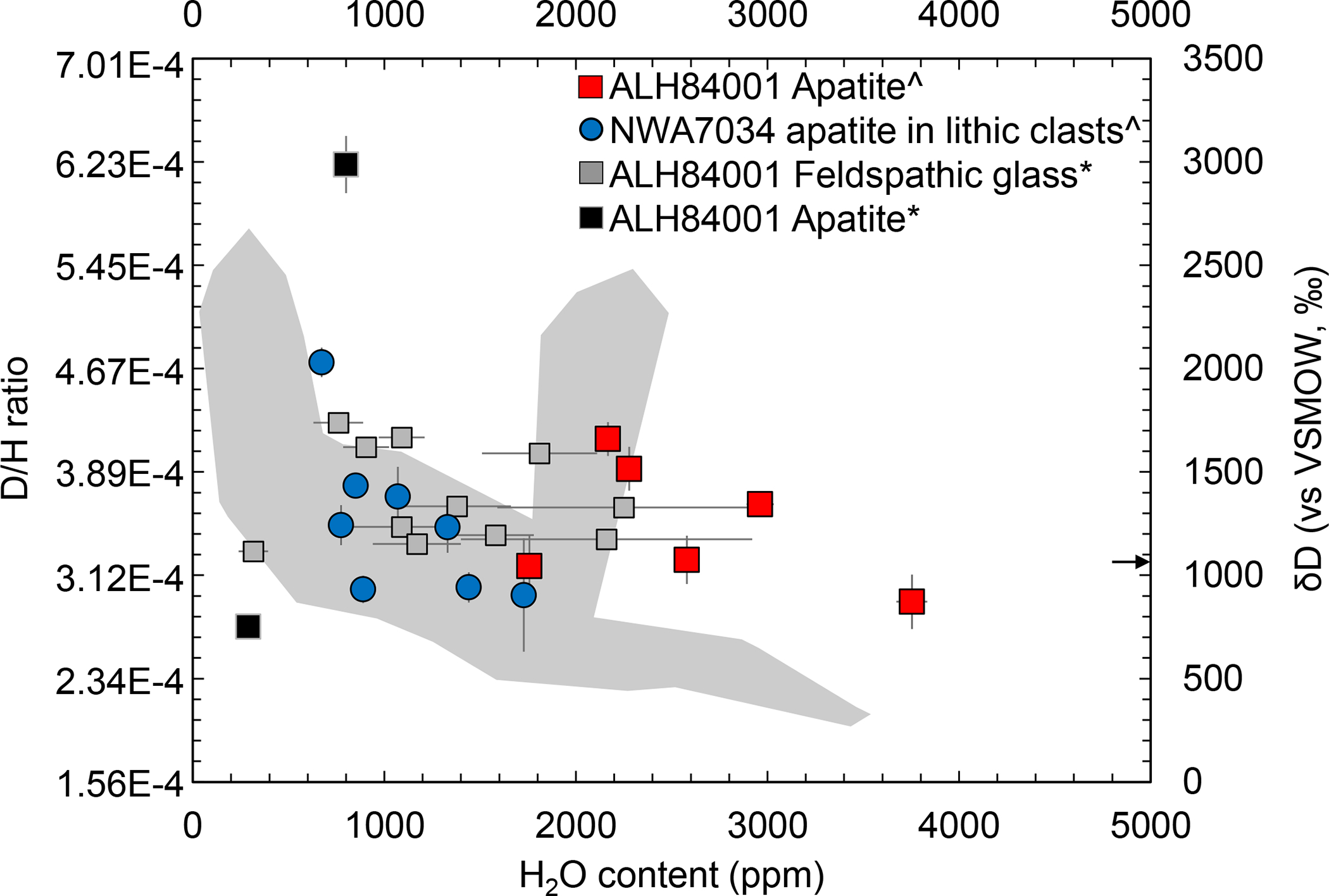

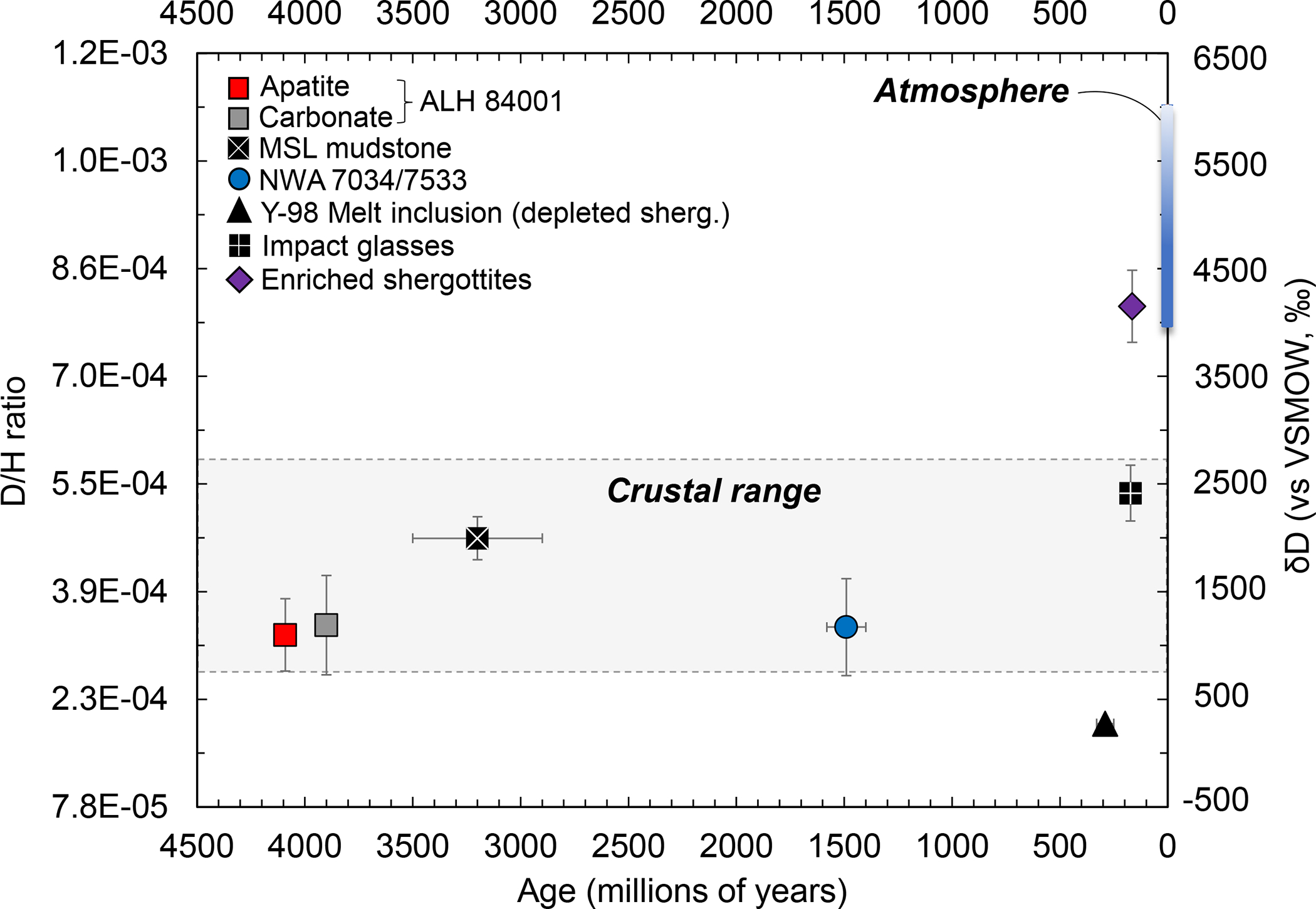

Allan Hills 84001 is an orthopyroxenite that crystallized in the crust ~4.1 billion years ago10,11 and experienced hydrothermal alteration with crustal fluids at about 3.9 billion years ago12. Northwest Africa 7034 and its pairings represent a regolith breccia of basaltic bulk composition13 that was lithified through thermal annealing in the presence of crustal fluids at about 1.5 billion years ago14. Together, these meteorites provide means of assessing the H-isotopic composition of water in the martian crust at two endpoints separated by ~2.4 billion years. The mineral apatite (Ca5(PO4)3[OH,F,Cl]) is the only hydrous mineral common to both samples, hence it was used to assess the H2O content and H-isotopic composition of the martian crustal samples by nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (Methods). Apatite grains within these samples both display a similar spread in D/H ratios (between ~3.12 and 4.67 × 10−4) over a wide range of water contents (Figure 1). The data for both samples are in agreement with H-isotopic data on other lithic clasts in NWA 7034 and its pair NWA 753315,16 and intercumulus apatite in ALH 8400117. Our results are also consistent with D/H values reported for the martian crust within the time span of 0.7 to 472 million years before the present (D/H ratio ~3.12 to 5.73× 10−4)18 and analyses of Hesperian (~3 Ga old) clays by the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument onboard the Mars Science Laboratory rover (D/H ratio of 4.67 ± 0.31 × 10−4)8. Combined, these results indicate that the martian crust is characterized by D/H ratios that are depleted in deuterium relative to the current martian atmosphere (Figure 2) over a timespan of at least the last 3.9 billion years with a bulk crustal D/H ratio ranging from 2.68 to 5.73 × 10−4.

Figure 1. Hydrogen isotopic composition versus H2O content of mineral phases in martian crustal lithologies.

Our new data demonstrates that both rocks sampled water of similar D/H ratio. VSMOW is Vienna standard mean ocean water. Uncertainties are 2 sigma analytical error. Data sources: ^ refers to data from this study, compiled data for *ALH84001 feldspathic glass from Leshin et al.29, and ALH84001 apatite from Boctor et al.17. The gray cloud is for NWA 7034/7533 data from Hu et al.16 and Liu et al.15. The arrow points towards a single high H2O content value at 7200 ppm in ALH 8400117.

Figure 2. Age constraints on the hydrogen isotopic composition of the martian crust.

Despite the wide range in ages22, different materials representing the martian crust, including interactions with fluids, show similar D/H compositions. This crustal signature is distinct from the enriched shergottite source, the present-day atmosphere2–4, and the light mantle defined by a subset of depleted shergottites6,23,27. Uncertainties are one standard deviation about the mean. Any range in age22 is smaller than the symbol size. Note that the enriched shergottite age is the average age of four samples (Grove Mountains 020090, Larkman Nunatak 06319, Los Angeles, and Shergotty), for data and methods see22.

The crust as the dominant water reservoir on Mars

The crust is the largest reservoir of water per unit mass on Mars with an estimated H2O abundance of 1410 ppm9. This reservoir represents approximately 35% of the total budget of water on Mars, and our results indicate that this major water reservoir has had a fairly consistent H-isotopic composition since the first 660 million years of Mars’ history (Figure 2). The martian crust is comprised of partial melting products of the martian mantle that have erupted onto the surface or stalled within earlier-formed crust over the last 4.55 billion years19,20, so the crust likely reflects geochemical signatures from the martian mantle as well as any surficial hydrosphere/atmosphere at the time of emplacement. Consequently, the H-isotopic composition of the martian crust either reflects mixing of isotopically distinct mantle reservoirs, reflects the amount of atmospheric loss of H that occurred within the first 660 million years of Mars’ history during the period of time Mars was thought to have a global magnetic field21, or a combination thereof. To discern between these possible models, we have compiled and evaluated H-isotopic data from martian meteorite samples that are thought to represent partial melts of the martian mantle22. In particular, we evaluated H-isotopic compositions relative to other geochemical indicators of mantle source character given that it has been long recognized that basalts from the martian interior arise from at least two geochemically distinct mantle reservoirs, referred to as the depleted shergottite source and the enriched shergottite source. Moreover, recent studies have shown that there are differences in H2O abundances between the enriched and depleted shergottite sources with the enriched source having 36–72 ppm H2O and the depleted source having 14–23 ppm H2O9. Details regarding other geochemical distinctions between these mantle reservoirs are provided in the supplementary information22 accompanying this article.

Distinguishing multiple mantle H reservoirs

Previous work converged on the idea that the martian mantle has a lower D/H ratio than the atmosphere6,23, although there has been some debate as to the most appropriate value of the mantle D/H ratio6,24,25. The most popular interpretation of a mantle signature6,7,18 recorded in shergottites is a D/H ratio of ~1.99 × 10−4 from an olivine-hosted melt inclusion in the depleted olivine-phyric shergottite Yamato 9804596. Departures of H-isotopic compositions of phases within shergottites from this “mantle” value are typically attributed to secondary processes such as contamination by fluids, shock implantation of D-rich modern atmosphere, and/or contribution from terrestrial contamination17,18,23–27.

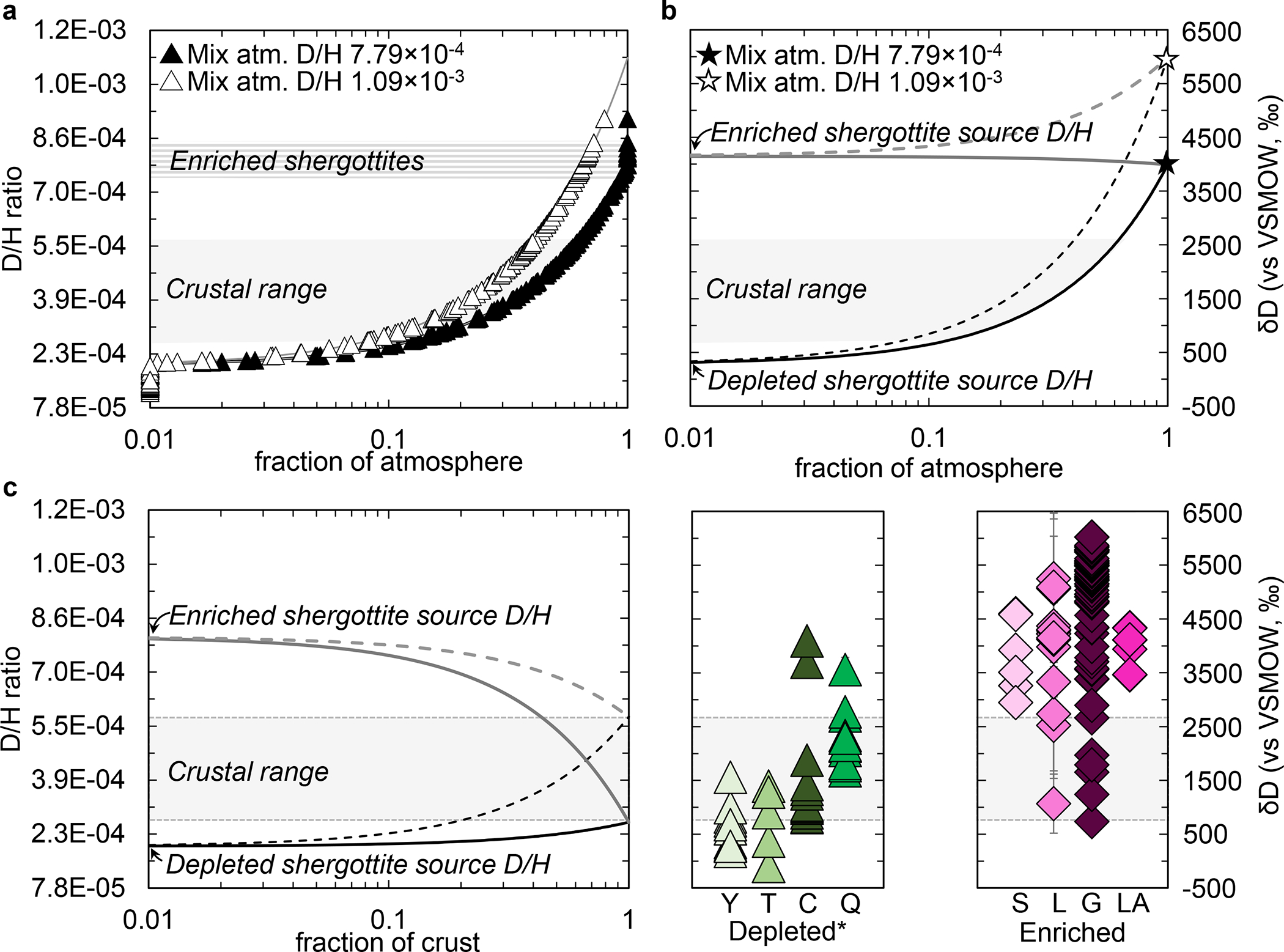

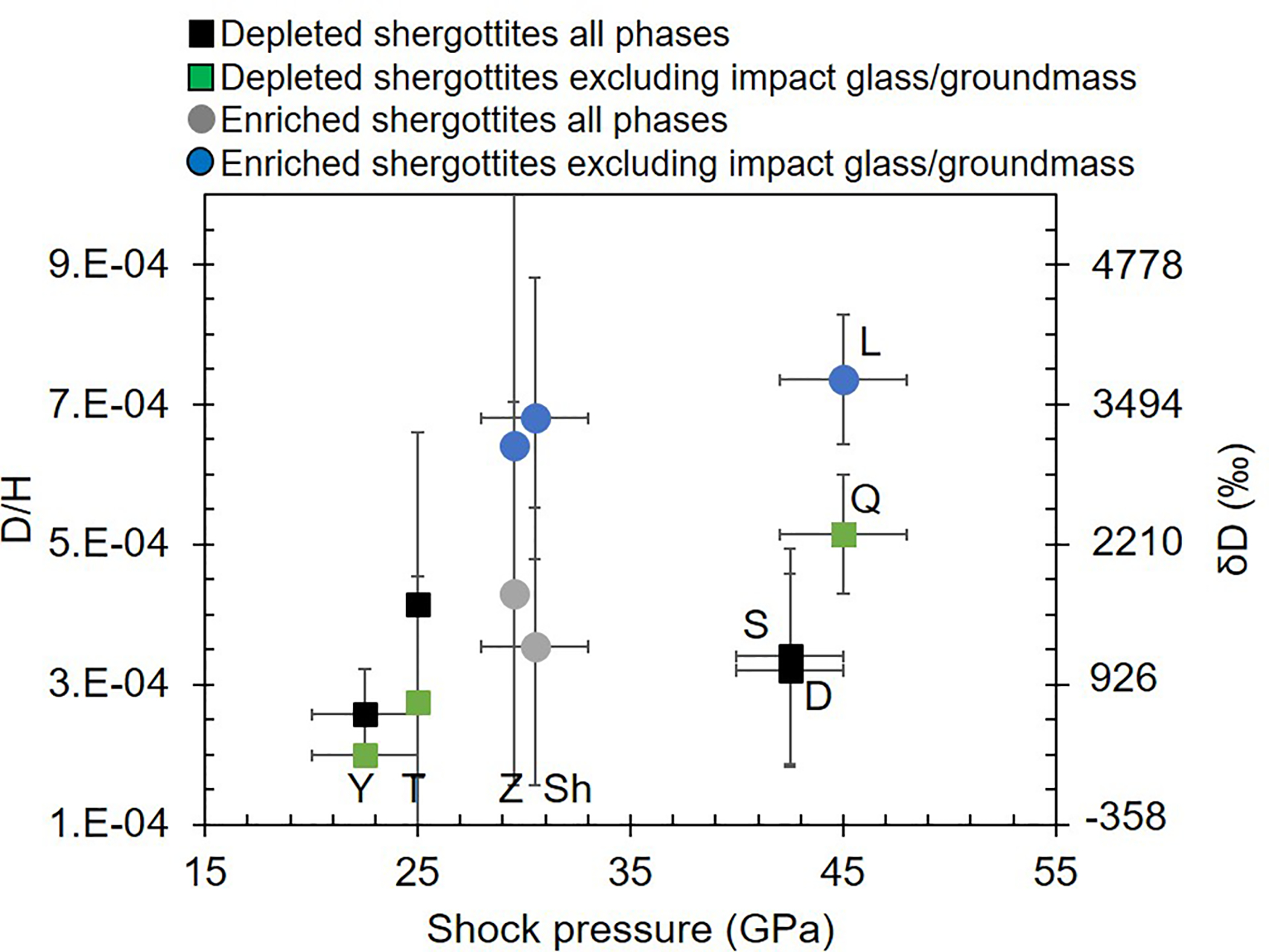

When a holistic and texturally constrained view of the hydrogen isotopic compositions of shergottites are considered, the enriched shergottites are significantly more D-rich7 (average D/H ratio of 8.03 ± 0.52 × 10−4, see Methods) than the crust and within the range of reported values for the martian atmosphere. In contrast, the depleted shergottites show much more variable intra-phase and intra-sample D/H ratios from 1.21 × 10−4 to > 8.57 × 10−4 (Figure 3a). We modeled the D/H variation observed in shergottites as if it was the result of simple two-component mixing between a D-poor mantle and D-rich modern atmosphere (Methods), as suggested by previous studies18,23–26. The results imply that this process must have been more effective or selective in replacing hydrogen in enriched shergottites compared to depleted shergottites. The former of which require almost complete overprinting of initial D/H by the martian atmosphere (Figure 3a–b) within multiple phases that host a wide range of H2O abundances and occur in a variety of textural regimes within the samples (Methods). In fact, the compiled D/H and shock pressure data reveal that shock implantation of hydrogen cannot account for the D/H systematics of the enriched shergottites (Extended Data Figure 1), and this refutes shock-implanted atmospheric contamination as a sole explanation for the observed D/H variation in shergottites22.

Figure 3. Mixing models and texturally constrained observations used to define multiple mantle H reservoirs.

The mixing calculations simulate the atomic replacement of hydrogen in martian basalts by the martian atmosphere. We assumed that when the martian mantle partially melted to produce shergottites the partial melts retained the D/H of their respective mantle source regions (Methods). (a) Shows the mixing curves between the depleted shergottite-like D/H and the atmosphere. Plotted along the curves are the D/H data for the depleted shergottites (Methods). The x-axis shows the fraction of atmospheric D/H needed to explain the observed D/H ratios. The D/H of the atmosphere was varied on the basis of two endpoints2–4. (b) Shows the mixing of both enriched and depleted shergottite mantle values with the atmosphere defined for two endpoint D/H ratios2–4. (c) Shows the mixing lines between the low D/H depleted shergottite mantle with crustal H2O and high D/H enriched shergottite mantle with crustal H2O. Also plotted in panel C are the values and 2σ analytical errors for samples derived from geochemically depleted* sources (Y-98, Tissint, Chassignites, QUE 94201) and enriched shergottites (Shergotty, Larkman Nunatak 06319, Grove Mountains 020090, Los Angeles). Both groups of samples show evidence of mixing between mantle and crustal water.

Although large intrasample variation in D/H is observed for depleted and enriched shergottites as well as other martian meteorites like the chassignites, many samples exhibit limited ranges in D/H that do not span the full range of values between the canonical light mantle and heavy atmosphere. Consequently, we also evaluated the D/H data in martian meteorites in the context of mixing between a mantle source and the martian crust (Figure 3c). The variation in D/H of enriched shergottites extend between a lower D/H endmember that is within the range we define for the martian crust and a high D/H endmember we infer to be representative of their mantle source. The depleted shergottites and chassignites, which originate from geochemically depleted portions of the martian mantle, exhibit at least two types of intrasample D/H variation. One type is best represented by the olivine-phyric shergottites Yamato 980459 and Tissint, which exhibit variation in D/H that extend between a high D/H endmember that is within the range we define for the martian crust and a low D/H endmember that we and previous studies have inferred to be representative of their mantle source (Figure 3c). The second type is best represented by chassignites and Queen Alexandra Range (QUE) 94201, which exhibit variation in D/H that extend between a low D/H endmember that is within the range we define for the martian crust and a high D/H endmember that we infer to be representative of their mantle source17,24,28,29 (Figure 3c). Importantly, the geochemistry of Chassigny refutes an atmospheric component30,31, although it may have exchanged with crustal H2O32,33, and the bulk composition of QUE 94201 refutes significant crustal assimilation34,35, so the source of the elevated D/H may not be from the martian crust (see Methods). These observations indicate the geochemically depleted mantle source(s) is heterogeneous with respect to D/H ratio and raise the possibility that heavy hydrogen was redistributed within the mantle from the relatively wet enriched shergottite source to the relatively drier depleted sources9 by mantle metasomatism.

The H-isotope data for martian meteorites clearly indicates that the martian mantle has at least two isotopically distinct mantle reservoirs, with one mantle reservoir characterized by a D/H ratio of ~1.99 ± 0.02 × 10−4 that is associated with a subset of geochemically depleted martian basalts and the other source characterized by a D/H of at least 8.03 ± 0.52 × 10−4 that is associated with the geochemically enriched martian basalts. This model rejects the paradigm of a single H-isotopic reservoir in the martian mantle6,7, and it relaxes previous requirements of pervasive atmospheric contamination of all the enriched shergottites (Figure 3b), although atmospheric contamination is certainly an explanation for elevated D/H ratios in some samples25,26.

Formation of a geochemically heterogeneous mantle

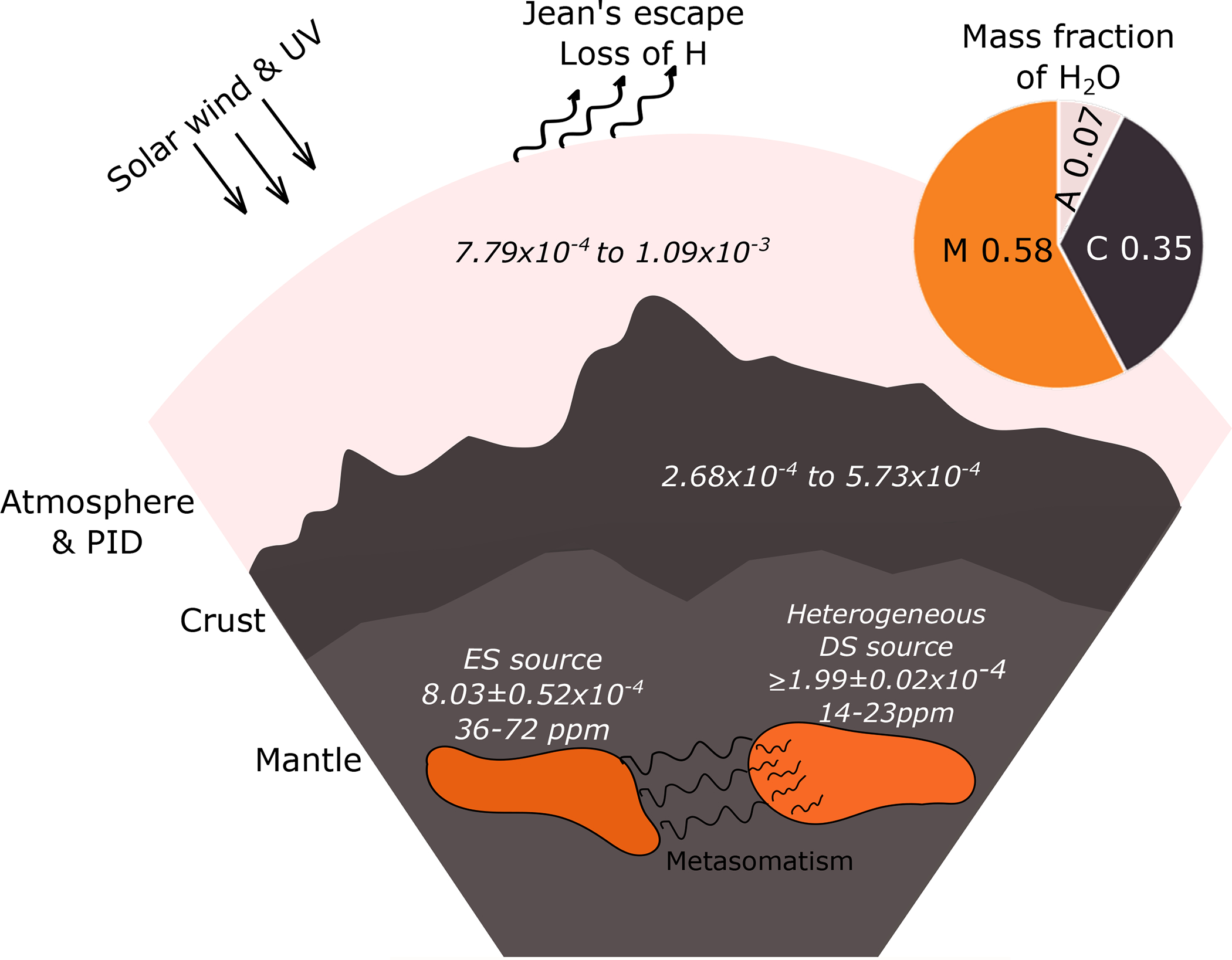

The existence of at least two distinct H-isotopic reservoirs within the martian mantle indicates that the H-isotopic composition of the martian crust represents, at minimum, a mixture of two mantle reservoirs and may also represent a third component defined by the primordial atmosphere/hydrosphere within the first 660 million years of Mars’ history (Figure 4); although, pristine crustal samples that are older than 3.9 Ga are needed to characterize the D/H ratio of the primordial surface hydrosphere/atmosphere of Mars. The presence of at least two isotopically distinct H-isotopic reservoirs in the martian mantle has important implications for the differentiation and subsequent thermochemical evolution of Mars. The ages of the depleted and enriched shergottite sources indicate that they are both primordial features of the martian interior36,37. Previous models have called upon multiple episodes of melting in the primordial martian mantle to account for the geochemical differences in source character between the depleted and enriched shergottites36,38. However, melting processes at pressure cannot account for the stark differences in H-isotopic composition between the depleted and enriched sources. Consequently, these features may have been inherited from the primary building blocks that constructed Mars39–41, implying that the martian mantle has almost always been heterogeneous because it was poorly mixed during accretion, differentiation, and its subsequent thermochemical evolution22. These results call into question the canonical model of differentiation on Mars via a globally extensive magma ocean, which would have worked to homogenize H-isotopic and other geochemical differences among disparate planetary building blocks. Additional studies are needed to further evaluate the efficacy of a globally extensive magma ocean on Mars, but the preservation of two distinct H-isotopic reservoirs in the martian mantle is an important new paradigm for any model to describe the formation, differentiation, and physicochemical evolution of Mars40,42.

Figure 4. Illustration showing the present-day hydrogen reservoirs in and on Mars.

The mass fractions (pie chart) of martian H2O are based on the mass of H2O in the bulk crust, mantle, and the combined inventory of the modern polar ice deposits and the atmosphere3,9. The mantle mass fraction is the combination of depleted and enriched shergottites. For data sources see Methods.

Methods

Scanning electron microscope analysis

Two standard polished thin sections of NWA 7034 (IOM numbers: 1B,2 and 2,3) were analyzed as well as two thin sections of ALH 84001 (thin section numbers:, 7 and, 205). Thin sections of NWA 7034 were characterized for a previous study by Santos et al.43. Detailed imaging of the target grains for this study were made using a Quanta 3D Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscope (FIB SEM) at the Open University (OU), Milton Keynes, U.K, fitted with an Oxford Instruments INCA energy dispersive X-ray detector. Thin sections were coated with carbon and analytical conditions followed those used in previous studies (e.g., Barnes et al.44). Thin sections of ALH 84001 were characterized using the JEOL 7600F SEM at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, TX, U.S.A. Each thin section was carbon coated with ~15 nm of carbon and X-ray mapped using an accelerated electron beam of 15kV and 1.5 nA.

Back-scattered electron (BSE) and secondary electron (SE) images of the phosphates analyzed by NanoSIMS from NWA 7034 and ALH 84001 are provided in the Supplementary Information22. For NWA 7034 clast numbers and lithologies were previously described by Santos et al.43. Clasts analyzed in NWA 7034 include iron, titanium, and phosphorous-rich (FPT) clasts (#2 and #64), basaltic clasts (#3, #5, #75), and a trachyandesite clast (#76).

Electron probe microanalysis

Chemical analyses of apatites in lithic clasts in NWA 7034 have already been reported in McCubbin et al.9 and those data were utilized in this study (see22). Electron probe microanalysis was performed on apatites in thin sections of ALH 84001 using the JEOL 8530F at JSC. Data were collected using both the JEOL manufacturer’s software and the Probe for EPMA (PFE) software from Probe Software, Inc. All apatites were analyzed using a 15 kV accelerating voltage and 20 nA beam current following previous procedures established by our group for the analysis of apatite in planetary materials43,45. We analyzed the elements Si, Fe, Mg, Mn, Ca, Na, P, Al, Y, Ce, F, Cl, and S in each apatite. Fluorine was analyzed using a light-element LDE1 detector crystal, and Cl was analyzed using a PETL detector crystal. The standards were as follows: for Ca a Durango apatite46 was used as the primary standard, for P SPI apatite was used as the primary standard, and a natural fluorapatite from India (Ap020) from McCubbin et al.47 was used as a secondary check on the standardization. A synthetic SrF2 crystal from the Taylor multi-element standard mount (C.M. Taylor) was used as the primary F standard, and Ap020 was used as an additional check on the F standardization. A tugtupite crystal was used as a primary Cl standard. A barite crystal from the Taylor multi-element standard mount (C.M. Taylor) was used as the primary S standard. Rhodonite, albite, diopside, and olivine from the Taylor multi-element standard mount (C.M. Taylor) were used as a primary standard for Mn, Na, Si, and Mg, respectively. Ilmenite from the Smithsonian (USNM 133868) was used as a primary standard for Fe. Ce and Y were standardized using their respective synthetic orthophosphate endmembers from Jarosewich and Boatner48. In order to reduce or eliminate electron beam damage, we used a 5 μm spot for standardization and 1–5 μm diameter beams for analysis of apatite grains in the martian samples.

After analysis by electron microbeam techniques, the carbon coatings were removed from the thin sections using a clean soft polishing pad and isopropanol (IPA) alcohol. The samples were all cleaned in IPA in an ultra-sonication bath and stored in a vacuum oven at ~60°C until they were gold coated for SIMS analysis.

Ion probe microanalysis

The CAMECA Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer (NanoSIMS) 50L ion probes at (1) The OU and (2) JSC were used in this work. Analyses followed similar protocols to those detailed in previous studies (e.g.,44,49,50). Specifically, NWA 7034 was analyzed using the OU NanoSIMS, and ALH 84001 was analyzed using the NanoSIMS at JSC. Note that here and in the figures we present H-isotopic compositions using standard delta notation, where δD = ((D/Hsample/D/HVSMOW)-1)×1000, where VSMOW is Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water with a D/H ratio of 1.557×10−4. Details of assessment of background H are provided in22.

Technical protocol

Thin sections were gold coated prior to ion probe analysis, ~30 nm Au was used at the OU and ~10 nm Au coat at JSC.

(1) The OU NanoSIMS was operated in multi-collection mode over two analytical sessions in 2015. A large Cs+ primary beam of ~ 300 pA was rastered on the sample surface over ~12 μm ×12 μm area during pre-sputtering (to eliminate surface contamination) and ~ 5μm × 5 μm area during analysis. For the analysis, secondary ions of 1H, 2H, 13C, and 18O were collected simultaneously from the central 6.25 μm2 area of each raster area on electron multipliers for ~20 min. An electron flood gun was used for additional charge compensation and tuned to minimize its contribution to the background. The mass resolving power was set to ~4000.

(2) The JSC NanoSIMS was operated in multi-collection mode. A large Cs+ primary beam of ~ 700pA current was rastered on the sample surface over a 20μm × 20μm area during a ~5-minute pre-sputter to eliminate any remaining surface contamination. For the analysis, areas of ~10μm × 10μm were rastered and signal was collected from central regions of between ~19 and 25μm2, negative secondary ions of 1H, 2H, 13C, and 18O were collected simultaneously on electron multipliers during the ~15-minute analysis. An electron flood gun was used for additional charge compensation and tuned to minimize its contribution to the background. The mass resolving power was set to ~4000.

Calibration and error analysis

(1) Reference apatites were used for calibrating water contents in unknowns and for establishing and correcting for instrumental mass fractionation. These standards included Ap018 (~0.2 wt% H2O), Ap003 (~0.06 wt.% H2O), and Ap004 (~0.55 wt.% H2O) (details in McCubbin et al.47). The 2σ uncertainty on the calibration slope varied between 2 and 3 % over the two sessions. Reference apatite Ap004 was used to correct measured D/H ratios for instrumental mass fractionation (IMF) in both sessions. The reproducibility of the D/H ratios measured on the reference apatites varied from 8 ‰ to 40 ‰ (2σ) in session 1 and from 28 ‰ to 52 ‰ (2σ) in session 2.

For unknowns, the H2O contents and D/H ratios, given using standard delta (δ) notation with respect to the D/H ratio of the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), and corrected for IMF based on repeated measurements of reference apatites, are reported with their 2 sigma uncertainties derived from the reproducibility of associated blocks of standard analyses (usually 4 analyses per block) and the internal precision of each analysis.

(2) The reference apatites used at JSC (different crystals mounted in indium) included Ap018 (~0.2 wt% H2O), Ap003 (~0.06 wt.% H2O), and Ap005 (~0.37 wt.% H2O)47. The 2σ uncertainty on the calibration slope was ~4 % during the analytical session. Reference apatite Ap018 was used to correct measured D/H ratios for IMF. The reproducibility of the D/H ratios measured on the reference apatites varied from 16 ‰ to 28 ‰ (2σ standard deviation).

Secondary ion images of 1H and 13C were monitored during pre-sputtering to further ensure that the analyzed areas were free of any surficial contamination, cracks, or hotspots. Unfortunately, hidden cracks often appeared during analysis of apatites in the martian rocks. In such cases, only portions of the secondary ion signal corresponding to analysis of pristine material were considered, and further processing was performed using the NanoSIMS DataEditor software developed by Frank Gyngard while at Washington University St Louis. Data inclusion was based on the 13C signal, which is low in martian apatites but which is several orders of magnitude higher for crack-filling material. This technique has been validated previously49.

The data obtained in this study are provided in Supplementary Table 1 and are plotted in Figure 1. The apatites analyzed are shown in Supplementary Figures 3 to 9.

Computing isotopically distinct reservoirs

The geochemically depleted shergottites display a large range in δD values from ~−222 to 4867 ‰7,22. In this study the average D/H ratio of each sample was used to define a weighted average to avoid bias from well-studied samples. The weighted average δD value of depleted shergottites is 1369 ± 632 ‰22 (standard deviation, n = 157, nsamples = 5,6,17,18,23,27,29,51,52). However, there are large ranges within individual melt inclusions, feldspathic glass inclusions, phosphates, and olivine. The large range in D/H of the depleted shergottites, on the surface, looks to be consistent with previous models proposing mixing between a light mantle reservoir and a heavy atmospheric reservoir (Figure 3a); however, when the range of D/H ratios for individual samples of depleted shergottites are compared, many samples exhibit limited ranges that would be more consistent with crustal assimilation (Figure 3c), although some samples do exhibit the entire range of values.

Yamato 980459 (Y-98) has been one of the defining samples for understanding the geochemical nature of the depleted shergottite source6,53–58, and Usui et al.6 reported a light D/H value for an olivine-hosted melt inclusion for Y-98. Furthermore, groundmass glasses in Y-98 exhibit a range of δD values18 between 181 and 1562 ‰ (Figure 3c). Additionally, melt inclusions in the depleted shergottite Tissint, which was a fall and hence has had limited uncontrolled exposure to the terrestrial weathering environment, exhibits a range of D/H ratios23,27 that are similar to melt inclusion and groundmass glass data6,18 from Y-98 (Figure 3c). Consequently we utilized the D/H ratio6 of an olivine-hosted melt inclusion in Y-98 to represent an upper limit on the depleted mantle D/H, which overlaps with some Tissint olivine-hosted melt inclusions23,27 and also other values commonly considered ‘martian mantle’6,7,18,59. The ranges of D/H values of Tissint and Y-98 span between a light mantle source and the range of values we present for the martian crust (Figure 3c), although we cannot rule out mixing between a light mantle source and small amounts of atmosphere. It is important to note that some samples from depleted sources have elevated D/H ratios41 that cannot be attributed to having come from a mantle source with low D/H ratios. The ranges in D/H values of QUE 94201 and Chassignites17,24,28,29 span between a high D/H end-member and the range of values we present for the martian crust (Figure 3c). Based on other geochemical indicators, these high D/H ratios are inconsistent with mixing of either crustal8,34 or atmospheric30,31 D/H, respectively. Data from QUE 94201 indicates the presence of a heavy hydrogen component in depleted martian mantle, whereas data for Chassignites could represent mixing between such a heavy component and crustal water (Figure 3c). The enriched shergottites also span a large range of values from −204 to 6830 ‰, however, most of the in-situ measurements of minerals (excluding nominally anhydrous minerals) and melt inclusions in the geochemically enriched martian shergottites yield a range in δD values from ~512 to 6830 ‰, and a weighted average of 3876 ± 730 ‰ (standard deviation, n = 99, nsamples = 5;6,24,25,59–61). If we consider petrographic and textural constraints, and core-rim variations, a more appropriate value of 4158 ± 336 ‰ is obtained (standard deviation, n = 22, nsamples = 4,6,25,60,61). These values overlap and provide confidence that the enriched shergottite source is isotopically distinct from that of the depleted shergottites. We utilized the weighted average value of 4158 ± 336 ‰ in our calculations, but we note that the δD value of the enriched shergottite mantle source is likely higher than this value.

A compilation of literature data used in this study can be found in Supplementary Table 2. It includes H isotope data previously published for NWA 7034 (and paired samples) and ALH 84001. We also compiled in-situ H isotope data for enriched and depleted shergottites, as well as other geochemical information relevant to the discussion portion of this work.

Mass balance calculations

The relative mass of water in each martian reservoir was calculated for use in subsequent mixing models. For this task, the water contents in each reservoir determined by McCubbin et al.9 were utilized. Those values are ~1410 ppm H2O in the crust, 36–72 ppm H2O in the enriched shergottite source, and 14–23 ppm H2O in the depleted shergottite source. In addition to these reservoirs, there is the surface atmosphere/hydrosphere that includes ~100 ppm H2O in the present-day martian atmosphere3 and the present-day polar ice deposits, which are estimated to constitute a global layer on the martian surface of 34 meters in thickness62. Based on these values, the mass of water in the crust, exclusive of the atmosphere and surface hydrosphere, is estimated to be ~2.33×1019 kg H2O (see McCubbin et al.9), and the mass of water in the martian atmosphere/surface cryosphere is estimated to be 4.91×1018 kg H2O3,9,62. We cannot differentiate the relative amounts of water between the enriched and depleted shergottite mantle sources with respect to the entire mantle as we do not know the relative size/distribution of each source. However, McCubbin et al.9 estimated that the bulk silicate Mars has 137 ppm H2O, which when we subtract the contributions from the crust and from the atmosphere and surface polar ices, means there is ~3.84 × 1019 kg H2O in the mantle (computed from McCubbin et al.9). This allows us to compute the relative mass fractions of water hosted in the atmosphere/hydrosphere, crust, and mantle to be 0.07, 0.35, 0.58, respectively (Figure 4).

Hydrogen isotope mixing models

Binary (linear) mixing calculations were performed to simulate the atomic replacement of hydrogen in martian basalts by martian atmosphere (Figure 3). These are not constrained by mass-balance of water (see below). These calculations were used simply to show how much atmospheric replacement of hydrated components would be required in martian basalts to explain the data observed in chemically distinct shergottites. We assumed that when martian shergottites partially melted, they retained the original D/H of their source, i.e., 1.99×10−4 (from Usui et al.6) and 8.03×10−4 (see above) for the depleted and enriched shergottite sources, respectively. The atmosphere2–4 was assumed to have a D/H of either 7.79×10−4 or 1.09×10−3. Complete replacement of mantle D/H was achieved when the fraction of atmosphere reached a value of 1. Panel A in Figure 3 shows the mixing of water between depleted shergottites and the atmosphere, which is the previously proposed model to explain variations in D/H of martian samples18,23–26. Plotted along the line are all of the data available for depleted shergottites22. The curve was used to calculate the fraction of atmospheric D/H (or % replacement) needed to explain the departure of the observed D/H data from a source with low D/H (7.79×10−4). Note that some depleted shergottite data cannot be explained by atmospheric replacement as modeled here (i.e., those data that have lower D/H than Y-98 melt inclusion).

When the enriched shergottites are considered, the results show that if a Yamato 980459-like D/H is assumed for their source, then almost complete replacement of mantle-like D/H is required for a majority of enriched shergottite samples in order to reproduce the measured D/H values (Figure 3). Specifically, when the atmospheric value is 7.79×10−4 using the curve in Figure 3a, ~70% of the data for enriched shergottites require more than half of the initial D/H (i.e., at 0.5 fraction) to be replaced by that of the atmosphere, compared to only 35% for the depleted shergottites. The crust lies between ~0.1 and 0.6 of the fraction of the atmosphere.

When mixing of a heavy enriched shergottite source is also considered (Figure 3b) then there is little difference in the resultant D/H with atmospheric mixing for the enriched shergottite samples, unless the atmosphere has an extremely high D/H ratio (dashed line). This suggests that either the enriched shergottites have seen preferential replacement of D/H by the atmosphere compared to the depleted shergottites, or that the source for the enriched shergottites was already heavy before any mixing. Notably, if the enriched shergottite source does indeed have a distinct D/H, variations in the D/H among the shergottites (outside of textural or chemical evidence for atmospheric interaction) could be the result of D/H mixing between the two mantle sources and/or the crust (Figure 3b).

We also performed mass balance-constrained isotopic mixing models (Supplementary Figure 1) and details can be found in22.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. All new data associated with this paper will be made publicly available via The UA Campus Repository (https://repository.arizona.edu/).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1:

Plot showing the average D/H for minerals and glasses versus shock pressure for shergottites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by UK Science and Technology Facilities Council (grant # ST/L000776/1 to M.A. and I.A.F.). J.J.B. would like to thank the NASA Post-Doctoral Program for the fellowship under which part of the data collection and all the manuscript writing was performed. FMM was supported by NASA’s Planetary Science Research Program. We would like to thank the Meteorite Working Group and the curation office at NASA Johnson Space Center (JSC) for allocation of Antarctic meteorite ALH 48001,7 and, 205. The US Antarctic meteorite samples are recovered by the Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET) program which has been funded by NSF and NASA and characterized and curated by the Department of Mineral Sciences of the Smithsonian Institution and Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office at NASA JSC. Ann Nguyen is thanked for her assistance with NanoSIMS operations at JSC. Daniel Kent Ross is thanked for assistance with electron microprobe analysis at JSC.

Footnotes

Financial/Non-financial Competing Interests

We declare no financial or non-financial competing interests related to this work.

References

- 1.Filiberto J & Schwenzer SP Volatiles in the Martian Crust. (Elsevier, 2018). doi: 10.1016/C2015-0-01738-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villanueva GL et al. Strong water isotopic anomalies in the martian atmosphere: Probing current and ancient reservoirs. Science 348, 218–221 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krasnopolsky VA Variations of the HDO/H2O ratio in the martian atmosphere and loss of water from Mars. Icarus 257, 377–386 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjoraker GL, Mumma MJ & Larsen HP Isotopic abundance ratios for hydrogen and oxygen in the martian atmosphere. in Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 21, 991 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chassefière E & Leblanc F Mars atmospheric escape and evolution; interaction with the solar wind. Planetary and Space Science 52, 1039–1058 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usui T, Alexander CMOD, Wang J, Simon JI & Jones JH Origin of water and mantle-crust interactions on Mars inferred from hydrogen isotopes and volatile element abundances of olivine-hosted melt inclusions of primitive shergottites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 357–358, 119–129 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallis LJ D/H ratios of the inner Solar System. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 375, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahaffy PR et al. The imprint of atmospheric evolution in the D/H of Hesperian clay minerals on Mars. Science 347, 412–414 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCubbin FM et al. Heterogeneous distribution of H2O in the Martian interior: Implications for the abundance of H2O in depleted and enriched mantle sources. Meteoritics and Planetary Science 51, 2036–2060 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapen TJ et al. A Younger Age for ALH84001 and Its Geochemical Link to Shergottite Sources in Mars. Science 328, 347–351 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terada K, Saiki T, Oka Y, Hayasaka Y & Sano Y Ion microprobe U-Pb dating of phosphates in lunar basaltic breccia, Elephant Moraine 87521. Geophysical Research Letters 32, 1–4 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borg LE et al. The age of the carbonates in martian meteorite ALH84001. Science 286, 90–94 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agee CB et al. Unique meteorite from early Amazonian Mars: Water-rich basaltic breccia Northwest Africa 7034. Science 339, 780–785 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCubbin FM et al. Geologic history of Martian regolith breccia Northwest Africa 7034: Evidence for hydrothermal activity and lithologic diversity in the Martian crust. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 121, 2120–2149 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Ma C, Beckett JR, Chen Y & Guan Y Rare-earth-element minerals in martian breccia meteorites NWA 7034 and 7533: Implications for fluid–rock interaction in the martian crust. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 451, 251–262 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu S et al. Ancient geologic events on Mars revealed by zircons and apatites from the Martian regolith breccia NWA 7034. Meteoritics and Planetary Science 879, 850–879 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boctor NZ, Alexander CMOD, Wang J & Hauri EH The sources of water in Martian meteorites: Clues from hydrogen isotopes. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 67, 397–3989 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Usui T, Alexander CMOD, Wang J, Simon JI & Jones JH Meteoritic evidence for a previously unrecognized hydrogen reservoir on Mars. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 410, 140–151 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borg L & Drake MJ A review of meteorite evidence for the timing of magmatism and of surface or near-surface liquid water on Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research E: Planets 110, 1–10 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouvier LC et al. Evidence for extremely rapid magma ocean crystallization and crust formation on Mars. Nature 558, 586–589 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lillis RJ, Frey HV & Manga M Rapid decrease in Martian crustal magnetization in the Noachian era: Implications for the dynamo and climate of early Mars. Geophysical Research Letters 35, 2–7 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Supplementary Information.

- 23.Hallis LJ et al. Effects of shock and Martian alteration on Tissint hydrogen isotope ratios and water content. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 200, 280–294 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson L, Hutcheon ID, Epstein S & Stolper EM Water on Mars: Clues from deuterium/hydrogen and water contents of hydrous phases in SNC meteorites. Science 265, 86–90 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwood JP, Itoh S, Sakamoto N, Vicenzi EP & Yurimoto H Hydrogen isotope evidence for loss of water from Mars through time. Geophysical Research Letters 35, L05203 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y et al. Impact-melt hygrometer for Mars: The case of shergottite Elephant Moraine (EETA) 79001. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 490, 206–215 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mane P et al. Hydrogen isotopic composition of the Martian mantle inferred from the newest Martian meteorite fall, Tissint. Meteoritics and Planetary Science 51, 2073–2091 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giesting PA et al. Igneous and shock processes affecting chassignite amphibole evaluated using chlorine/water partitioning and hydrogen isotopes. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 50, 433–460 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leshin LA Insights into martian water reservoirs from analyses of martian meteorite QUE94201. Geophysical Research Letters 27, 321–333 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew KJ & Marti K Early evolution of Martian volatiles: Nitrogen and noble gas components in ALH84001 and Chassigny. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 106, 1401–1422 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ott U Noble gases in SNC meteorites: Shergotty, Nakhla, Chassigny. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 52, 1937–1948 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCubbin FM et al. A petrogenetic model for the comagmatic origin of chassignites and nakhlites: Inferences from chlorine‐rich minerals, petrology, and geochemistry. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 48, 819–853 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCubbin FM & Nekvasil H Maskelynite-hosted apatite in the Chassigny meteorite: Insights into late-stage magmatic volatile evolution in martian magmas. American Mineralogist 93, 676–684 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams JT et al. The chlorine isotopic composition of Martian meteorites 1: Chlorine isotope composition of Martian mantle and crustal reservoirs and their interactions. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 51, 2092–2110 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franz H et al. Isotopic links between atmospheric chemistry and the deep sulphur cycle on Mars. Nature 508, 364 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borg LE, Nyquist LE, Taylor LA, Wiesmann H & Shih CY Constraints on Martian differentiation processes from Rb-Sr and Sm-Nd isotopic analyses of the basaltic shergottite QUE 94201. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 61, 4915–4931 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borg LE, Nyquist LE, Wiesmann H, Shih CY & Reese Y The age of Dar al Gani 476 and the differentation history of the martian meteorites inferred from their radiogenic isotopic systematics. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 67, 3519–3536 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herd CDK The oxygen fugacity of olivine-phyric martian basalts and the components within the mantle and crust of Mars. Meteoritics and Planetary Science 38, 1793–1805 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chambers JE Planetary accretion in the inner Solar System. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 223, 241–252 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dauphas N & Pourmand A Hf-W-Th evidence for rapid growth of Mars and its status as a planetary embryo. Nature 473, 489–492 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCubbin FM & Barnes JJ Origin and abundances of H2O in the terrestrial planets, Moon, and asteroids. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 526, 115771 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang H & Dauphas N 60Fe-60Ni chronology of core formation in Mars. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 390, 264–274 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos AR et al. Petrology of igneous clasts in Northwest Africa 7034: Implications for the petrologic diversity of the martian crust. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 157, 56–85 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnes JJ et al. The origin of water in the primitive Moon as revealed by the lunar highlands samples. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 390, 244–252 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnes JJ et al. The origin of water in the primitive Moon as revealed by the lunar highlands samples. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 390, 244–252 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jarosewich E, Nelen JA & Norbers JA Referance Samples for Electron Microprobe Analysis. Geostandards Newsletter 68–72 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCubbin FM et al. Hydrous melting of the martian mantle produced both depleted and enriched shergottites. Geology 40, 683–686 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jarosewich E & Boatner LA Rare Earth Element Reference Samples for Electron Microprobe analysis. 15, 397–399 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tartèse R et al. The abundance, distribution, and isotopic composition of Hydrogen in the Moon as revealed by basaltic lunar samples: Implications for the volatile inventory of the Moon. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 122, 58–74 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barnes JJ et al. Accurate and precise measurements of the D/H ratio and hydroxyl content in lunar apatites using NanoSIMS. Chemical Geology 337–338, 48–55 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Y et al. Evidence in Tissint for recent subsurface water on Mars. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 425, 55–63 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuchka CR, Herd CDK, Walton EL, Guan Y & Liu Y Martian low-temperature alteration materials in shock-melt pockets in Tissint: Constraints on their preservation in shergottite meteorites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 210, 228–246 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basu Sarbadhikari A, Day JMD, Liu Y, Rumble D & Taylor LA Petrogenesis of olivine-phyric shergottite Larkman Nunatak 06319: Implications for enriched components in martian basalts. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 2190–2214 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 54.White DSM, Dalton HA, Kiefer WS & Treiman AH Experimental petrology of the basaltic shergottite Yamato-980459: Implications for the thermal structure of the Martian mantle. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 41, 1271–1290 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Usui T, McSween HY & Floss C Petrogenesis of olivine-phyric shergottite Yamato 980459, revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 1711–1730 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Symes SJK, Borg LE, Shearer CK & Irving AJ The age of the martian meteorite Northwest Africa 1195 and the differentiation history of the shergottites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 1696–1710 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shearer CK et al. Petrogenetic linkages among fO2, isotopic enrichments-depletions and crystallization history in Martian basalts. Evidence from the distribution of phosphorus in olivine megacrysts. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 120, 17–38 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peters TJ et al. Tracking the source of the enriched martian meteorites in olivine-hosted melt inclusions of two depleted shergottites, Yamato 980459 and Tissint. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 418, 91–102 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hallis LJ et al. Hydrogen isotope analyses of alteration phases in the nakhlite martian meteorites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 97, 105–119 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu S et al. NanoSIMS analyses of apatite and melt inclusions in the GRV 020090 Martian meteorite: Hydrogen isotope evidence for recent past underground hydrothermal activity on Mars. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 140, 321–333 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koike M et al. Combined investigation of hisotopic compositions and U-Pb chronology of young Martian meteorite Larkman Nunatak 06319. Geochemical Journal 50, 363–377 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carr MH & Head JW Martian surface/near-surface water inventory: Sources, sinks, and changes with time. Geophysical Research Letters 42, 726–732 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fritz J, Artemieva N & Greshake A Ejection of Martian meteorites. Meteoritics and Planetary Science 40, 1393–1411 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baziotis IP et al. The Tissint Martian meteorite as evidence for the largest impact excavation. Nature Communications 4, 1404–1407 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. All new data associated with this paper will be made publicly available via The UA Campus Repository (https://repository.arizona.edu/).